A Holistic Exploration from Origins to Contemporary

Introduction

This chapter looks to critically highlight and analyses the literature regarding sustainability in business and with a specific focus on the fast fashion industry

Sustainability

Sustainability is quite critical in human survival. While it can mean widely different things in different contexts and disciplines, it is defined as how biological systems endure and remain diverse and productive (Sharma et al., 2010: Georges, 2009). However, Grant and Kenton (2019) point out that sustainability in the current century goes beyond such narrow parameters and crucially refers to the need of developing models that are necessary for the survival and continuance of the human race and the entire planet. It is a complex construct to define, especially given its broad nature, which has to balance multiple factors to protect the Earth for future generations (Aras & Crowther, 2009). Sharma et al. (2010) emphasize that sustainability is rooted in a plethora of disciplines, meaning that taking an interdisciplinary approach is necessary to understand the theories adequately. The origins of sustainability date back over 130 years to the book "Progress and Poverty" written by a political economist (Henry Georges, 2009). He advocated that the Earth was a natural resource, and the economic value derived from the land should be equally shared amongst members of society while needing protection from industrialization and cyclic economies. Without this intervention, inequality and poverty would be irreversibly entrenched in culture (Georges, 2009).

In this age of pollution and excessive release of harmful materials and gases due to human activities, sustainability is a term also coined to prevent mindless exploitation and ensure the preservation of the environment and natural resources for the future generations (Hart and Milsten, 2003). In its purest form, the term sustainability was defined as a movement that sought to encourage individuals to value the natural environment and actively try to preserve it from further destruction (Shivastava & Hart, 1992). Hart & Milsten(2003) moreover, confirm that it is about living up to present generations' expectations without hindering future generations’ social and environmental needs. Elkington (1998) believed that as a society, we should focus on improving the Environmental factors before making any other progress. ForElkington (1998, pg55) “The consumption of renewable resources should be limited so as not to exceed the rates of regeneration. The non-renewable resources should only be used if there are consistent research and development into Sustainable alternatives. Additionally, pollution levels should be capped so that the assimilative capacity of the environment is not exceeded."

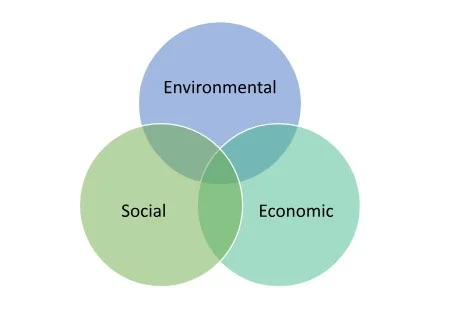

In the UK, three pillars guide organization activities in the execution of corporate sustainability. Beattie (2019) outlines the three components to include economic, environmental, and social sustainability, which are translated to people, planets, and profits in informal terms. The environmental Pillar takes into account the preservation and conservation of the environment and ensuring environmental conservation within a particular company’s operations. Purvis, Mao, and Robinson (2018) point out that at present companies focus on reducing the carbon footprint through recycling of the packaging material and ensuring lesser pollution of the environment.

The social pillar, on the other hand, is with concerns to the social responsibilities of an organization and whether or not organizations take responsibility for the social impacts of their activities. Beattie (2019) emphasize that a sustainable organization needs to have the support of its employees, customers, and stakeholders as well as the overall community it operates. Businesses should be able to implement retention and engagement strategies when it comes to their employees such as offering flexible schedules, learning, and improvement opportunities as well as essential requirements and rights such as maternity and paternity leaves. Also, the organization should be conscious of the communities they operate in through engaging in activities that help improve and influence the society positively through the mitigation of social evils such as hunger, poverty, and discrimination.

The Economic pillar of sustainability is associated with the financial performance and eventual profitability of the organization or company. Sustainable businesses include businesses that make profits regularly through their regular operations. Purvis, Mao, and Robinson (2018) highlight that this pillar is sometimes referred to like the governance pillar and is mainly concerned with the alignment of the board and management interests with the interests of the rest of the other stakeholders within the company and ensuring transparent accounting processes.

Sustainability in the Business Environment

Whilst sustainability cannot be accurately defined for any company or organization due to the full range of involvements these organizations and companies are in, it is considered a law as well as corporate social responsibility that all companies should engage in for the preservation of their immediate environment and resources and by extension throughout the entire globe (Emery, 2012). Throughout all discussions of sustainability amongst different scholars (Santos & Filho, 2005: Elkington, 1998: Hart & Milsten, 2003 and Georges, 2009), one reoccurring view that emerges sustainability prominently is an issue that needs to be weighed against its limitations. Essentially, it means that for the world to become sustainable, Individuals, businesses, and governments must consider the benefits and disadvantages of all possible actions and choose the one that complements most the values of sustainability (Alhaddi, 2015). As such, it is an individual company or organization’s decision as to what extent sustainability is actioned within their various tasks goals and objectives.

Whilst it has become a popular buzz-word, to refer to changes within society, the definition of the term varies among theorists, organizations, industries, and countries (Bateh et al., 2013), thereby making sustainability a problematic concept for consumers to understand and relate to (Kho, 2014). This leads to a lack of awareness and indulgence of the consumers in sustainability activities on their own. In addition, the consumers are not aware enough to engage in the sustainability activities that are highlighted by the brands they indulge with resulting in significant apathy and ignorance to the fact of the lack of boundaries to the earth’s timeline (Grant and Kenton, 2019). Whilst the concept is now embedded in the public domain, and a growing ethical consciousness has begun filtering throughout society, the impact of the movement is only now starting to pick up, urging businesses and political leaders to be more responsible for their actions considering both the environmental and social impact of their decisions (UNECE, 2017). A full evaluation of the concept of sustainability and the role of businesses and organizations in being able to champion sustainability to their consumers is crucial in enhancing sustainability and ensuring the preservation of resources for future generations.

However, to understand why consumers are failing to interact with the concept of sustainability adequately, an understanding of how businesses can be sustainable and how they can use their platform to encourage consumers to make wiser choices is crucial. This highlights the objectives of this study that consumers and Fast Fashion (FF) businesses must approach daily practices from a new perspective that has sustainability at the forefront to realize significant progress in reversing the damage already created through unconscious behavior. Textile systems and companies operate in a linear way producing large amounts of non-renewable resources extracted for cloth production. These resources, generally used for brief periods of time, often end up in landfills or are incinerated, thereby contributing to environmental pollution. Based on the Environmental Audit Committee (2019) less than 1% of materials used in cloth production are recycled leading to more than 300,000 tonnes of textile waste ending up in landfills or incinerated within the UK every year. Further, the UN Environmental Program (2018) highlights that the fashion industry is responsible for 20% of the global wastewater and 10% of global carbon emissions making it more lethal than international flights and maritime shipping pollution combined. Perry (2018) points out that it takes up to 2000 gallons of water to make a pair of jeans, these effectively makes textile dying the second largest polluter of water globally.

Business Sustainability

"The age of Sustainability has arrived, but now must fully drive through our economic system. As such, markets will have to continue to evolve to take into account the full environmental and social externalities of business. This shift will require nothing less than a complete change in mindset – one that views our planet as a long term investment, rather than a business in liquidation." - Vice President Al Gore in 2008 (Emery, 2012).

Based on the logic that as humans, we want to live as long and as healthily as possible, sustainability pulls on the concept that our children deserve similar opportunities. Therefore we should alter our destructive behavior to preserve the earth for future generations (Bansal & DesJardine, 2014). Therefore, business sustainability is ‘the ability for a company to fund their short-term financial needs without comprising theirs or others' ability to satisfy future needs (Clark, 2016). Attention on businesses to focus on their sustainability has increased with consumers requiring businesses to be more responsible and honest about their ‘business ethics’ (Colbert & Kurucuz, 2007). Strategies for sustainability now consider the changing macro-economic needs and demands. In addition, it also finds all trade-offs to create products or services designed to satisfy consumers and simultaneously meet the needs of the future (Bansal & DesJardine, 2014). Businesses must consider both their short and long-term strategies for sustainability. However, 80% of business executives sacrifice long-term sustainability, focussing mainly on achieving short–term targets through temporary value creation (Graham et al., 2005).

Economic Sustainability

Circular Economy

Linear Economy has proved it is no longer a sustainable business model. The reliance on what was once an unlimited supply of natural resources has led to wasteful practices that can no longer sustain themselves, as these once, abundant resources are now scarce (Cooper, 1999). The capacity for the earth to absorb waste and pollution has become part of the sustainability crisis due to the carelessness of businesses and governments alike. A shift in consciousness has become apparent towards what is known as a Circular Economy, an economic model that encourages corporations to be resourceful and innovate their business models to be more responsible for their output (Murray et al., 2017).

Circular Economy, otherwise known as the ‘Closed- Loop Economy’ was coined as the goal of all ecologically driven initiatives (Mathews & Tan, 2011). The concept of Circular Economy encourages businesses to look beyond the traditional industrial models and amend their existing perspectives so that we as a society can redesign how the economy works (Murray et al., 2017). Boulding (1966) argued to be the founder of the concept, expressed his belief that man must work with the existing Cyclical Ecological system and transition to resources that are capable of continuous renewal so that we can protect the ability to generate energy for future generations by transitioning away from non-renewable resources (Boulding, 1996). Recently it has been defined by the UNEP (2006) as a concept that balances economic development with environmental & resource protection. This connects the Circular Economy with the “Three Pillars of Sustainability, “the economic, social, and environmental pillars. This is because it is more than a preventative approach to the sustainability crisis from a positive perspective. By redesigning existing business models around renewable energy and resources, then the world can easily transition to a new economic system (UNEP, 2006).

In practice, the Circular Economy encourages firms to re-evaluate their practices, centralizing their business model around ensuring positive influences on society such as shifting their economic reliance on finite resources, minimizing waste from their practices, and using renewable energy sources (Murray et al., 2017). For example, the more a factory repurposes its waste, the closer it shifts to a Circular Economy and simultaneously enhances the firm's profit (Lancaster, 2002). Whilst the ideas surrounding the Circular Economy exists in the Western world, it has been more widely accepted as an alternative business model and has started being enforced in China through government legislation (Liu et al., 2009). This is what makes the circular economy quite practical and beneficial. Whilst other sustainability-driven concepts have failed to gain as much traction, and they are still predominantly theoretical ideas of how sustainability and economic growth can co-exist (Murray et al., 2017).

Marketers are adopting the principles of the Circular Economy business model to help build brand loyalty and incentivize customers to form a deeper relationship with the business, thus improving the sustainability for the individual and business. For example, mobile phone companies encourage consumers to trade their old phones in for in-store vouchers, enabling them to control the lifecycle of their products, resulting in consumers being happy to recycle whilst gaining a financial reward for their excellent practice (Gould, 2016).

Triple Bottom line

Sustainability is a broad and all-encompassing term interacting with most aspects of daily life. Previous discussions of sustainability embraced Environmental and Social pillars individually. John Elkington coined the term Triple Bottom line (TBL), incorporating all three components in 1998 (Elkington, 1998). The TBL framework was designed to measure universal sustainability reporting for businesses using the three pillars, namely Profit, People, and the Planet (Elkington, 1998). Elkington considered TBL a natural expansion of the Environmental agenda that emerged during the end of the 20th century and wanted to increase the awareness in improving Social Justice and Economic Prosperity for all by broadening the focus from Environmental Protection (Elkington, 2004).

The TBL framework pushed corporations to not only consider their economic sustainability but their environmental and social value to the world (Emery, 2010). Reports based on the TBL concept provide a framework for businesses to incorporate their financial and non –financial information, helping assess performance against social, environmental, and economic parameters. TBL is a concept many businesses have embraced, as a logical way of approaching corporate responsibility and public reporting. TBL enables the identification of the sources of irresponsibility within a business model suggesting solutions and reforms for sustainability (Colbert &Kurucz, 2000)

Social Line

In terms of the Social Line, Elkington (1997) sought to hold businesses accountable for their labor force, relationship with local communities, and human capital. As such, companies would have to reassess their business practices to ensure that they not only protect individuals but that business activities must also benefit individuals. The logic behind the Social Line is that businesses need to “give back” to society and that they should add value to local communities through their business model. When measuring the Social Line, one must look to how a business interacts with the society, for instance, there must be signs of community involvement, fair treatment of staff, reasonable wages and established employee relations (Goel, 2010) otherwise known as Corporate Social Responsibility in the current business environment. This creates a form of moral pressure for businesses to be "good" to society through the high regard of their own Social Responsibility, which influences not only their performance but also their reputation. The focus on Sustainable Business practices emerged from increased public demand for more responsible “Business Ethics” with demands for simple practices such as honesty and trustworthiness igniting this “trend” (Colbert &Kurucz, 2007).

Environmental Line

When formulated, Elkington (1997) wanted to build on the existing momentum of environmental protection. This line encourages businesses to engage in practices that do not compromise the availability of natural resources for future generations such as protecting energy resources, reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, minimizing their ecological footprint and protecting water sources from pollution, to name a few (Goel, 2010). A study from Kearney (2009) proved that when measured, firms that are actively investing in their Social and Environmental Sustainability are outperforming their industry peers, highlighting the importance of businesses investing in sustainable development. Those more hesitant at altering their business model fail to see the Economic gains that can be attributed to the long term benefits of reduced operational costs (savings made to water usage, energy, and less waste) (Kenny, 2009: Goel, 2010).

There is little empirical research when it comes to investigating the TBL of organizations (Goel, 2010); however, studies produced refer to each individual line and therefore are a way to ensure that sustainability is considered from every pillar’s angle, not just from an environmental perspective. Internally, TBL helps businesses manage their performance according to the three individual lines (Goel, 2010). One of the benefits of following the TBL is that firms that successfully integrate these concepts are likely to generate international recognition and goodwill for their initiatives (Colbert &Kurucz, 2007). By embracing and incorporating these three lines in their business models, they are likely as a result, to become industry leaders, thus attracting financial benefits, customer loyalty, and enhanced brand reputation. There has been much criticism of theory on ‘TBL’ as it would appear that many businesses only focus on their responsibility to consumers in order to retain their loyalty, in turn, neglecting them becoming more sustainable as this would require significant financial investment and inter-temporal trade-offs (Bansal &DeJardine, 2014).

Economic Line

Elkington (1997) views the Economic Line as the impact a firms business practices have on the economy of a country. The line ties the economic growth of the organization to the current economic state of the country and assesses how the business interacts with society and if the economic value provided in the present day is sustainable and achievable for future generations. The premise behind this line is that it is a subsystem of sustainability, and the only way we can support future generations is to carefully manage and evolve existing economic systems (Spangenberg, 2005). As climate change has emerged and the gap between rich and poor has widened, economic stability is threatened. Significant changes to existing business models must be undertaken if we want legitimate and long-term sustainability in all areas of the triple bottom line.

Sustainable Development and the emergence of the TBL mean that businesses need to retain their competitiveness and protect their financial stability whilst acknowledging the growing environmental crisis and societal demands (Danciu, 2013). When incorporating the three dimensions of sustainable development, businesses need to consider any potential conflicts or trade-offs so that they could create a viable strategy for development which is where marketing concepts emerged to help ensure the criteria of development was being met.

Shareholder and Stakeholder Theories

Economic sustainability is also significantly impacted by the orientation of the business model and design, whether stakeholder-oriented or Shareholder oriented. While the stakeholders have stakes in the success or the organization business or project, the shareholders are partial owners of the organization and as such are only interested in the return of investment that may not be in line with the delivery of respective projects. This lack of aligned interests often provides a dilemma and compromise when it comes to financial decision making, which may eventually impact the organization's economic sustainability.

According to Hunsacker (2018), the shareholder's theory highlight that corporate managers have a duty to maximize shareholder returns; the shareholders who are the owners of the business approve the corporation manager’s salary. The management, in turn, manages the corporations spending and ensure maximum ROI. On the other hand, the stakeholder's theory premises that the same business managers have an ethical duty to both the corporation's shareholders as well as the interests of the employees, customers, the community and generally any other stakeholders in the business or organization. These theories overall highlight a conflict in financial management within the organization or business, which may subsequently impact economic sustainability.

Sustainable Development Goals

The term sustainability has evolved since its conception in the 1980s and is now used openly and freely among businesses and governments signposting the environmental and social challenges and possible solutions to the issues faced in the 21st century (Emery, 2012; Kho, 2014). In being able to walk the walk, organizations, companies, and individuals must individually and collectively engage in activities that promote the sustainable use of all basic resources whether environmental, economic or social through aligning their objectives and goals to the sustainable development goals.

The United Nations Global Business Compact is an initiative to encourage businesses worldwide to be more aware of the Global Sustainable Development Goals by 2030.

This platform aims to drive businesses to start thinking about their own corporate social responsibility and the sustainability of their existing business model by explaining how the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) apply to any size business (Agarwal et al., 2017). Whilst seeking to leave no nation behind the goal surge multinational corporations to improve the sustainability of their supply chains management. This is often fundamentally unsustainable according to the SDGs goals, and these complex businesses need to reassess each layer of its business model identifying flaws lying within each individual component of their organizational structure and supply chains (Pederson, 2018). Furthermore, due to the nature of these multinational corporations, they must develop a comprehensive strategy to become sustainable (Lubin& Etsy, 2010). This will take time, and businesses need to embrace the transition to sustainability and consistently review and incorporate new measures throughout all layers of their businesses (UNECE, 2017). The sooner businesses embrace the concept, the easier and more successful they will be in adapting to the new business model (Lubin& Etsy, 2011).

SDGs hold all actors responsible for their individual output and most importantly, help businesses take more accountability over their actions and encourage them to be a part of a more sustainable future (Agarwal et al., 2017). The purpose of this framework is to raise awareness that ‘Business as usual' is no longer a satisfactory outlook, and that businesses that do not adapt and follow SDGs are likely to be left behind and their reputations destroyed.

SDGs provide a logical framework for businesses to follow and have been dubbed a ‘gift’ to businesses as these targets can help businesses find solutions to the existing issues. Swapping to sustainable alternatives is forecast to bring great economic success to businesses (Pederson, 2018). According to the UN, the SDG targets will help generate solutions that equate to over $12 trillion per annum in market opportunities, and due to the awareness and opportunities SDGs have created, over 380 million new & more sustainable jobs will be created by 2030. Figure 2displays the 17 different areas of sustainable development applicable to countries and businesses to follow in order to become more sustainable. Currently, they can assess their existing position on 169 different targets. Each target that is applicable to the organization in question is scored of either performing well, Performing Poor or Inadequate performance, thus providing structure to organizations on where they need to focus their attention.

However, businesses and governments have different responsibilities and goals, and therefore, the framework is not entirely relevant to all organizations. Therefore, The UN Secretary-General urges private sector businesses to adopt the framework believing the new opportunities that the relevant SDGs present will help improve the environment and rebuild markets to be more sustainable entities (Agarwal et al., 2017).

Corporate Social Responsibility

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) as a concept focuses on immediate acts of philanthropy, adding value for consumers, supporting local communities, and provide some form of benefit to the business. However, these initiatives do not need to be sustainable in the long-term and therefore being responsible in the short-term is often more appealing for firms leading to altering the business models aimed at strategizing for genuine sustainability (Bansal &DesJardine, 2014). It is important to understand what CSR is in relation to sustainability, as for a business, it must be responsible to society. However, sustainability is more than appealing directly to its primary consumers and therefore my dissertation will focus on sustainability rather than CSR as it is a more comprehensive strategy, that seeks on reversing the negative effects of capitalism long term by changing the way that we do business, rather than the short term solutions that CSR provides (Bansal&DesJardine, 2014).

CSR does not push businesses to make tactical trade-offs. CSR represents policies that are designed to be good for society and paint the firm positively (McWillliams & Siegel, 2001). This encourages firms to focus on their CSR rather than overall sustainability and encourages businesses to look at their individual responsibility from a “Win-Win” perspective. This means that it encourages brands to create benefits for the business and for consumers and society as a whole (Porter & Kramer, 2006), and also known as adding “Shared Value “which has prompted businesses to view their social responsibility as ‘good business’ ( Bansal&DesJardine, 2014).

Sustainability Marketing

The first form of Sustainable Marketing appeared in 1971 as pressure was placed on businesses to help deal with social and environmental issues. Macro marketing evolved during this time with several different strategies emerging that seeks to meet the needs of society (Kotler et al., 2002) namely "Societal Marketing" "Social Marketing," "Ecological Marketing," and "Green Marketing."

Sheth & Parvatiyar (1995) coined Sustainable Marketing as the “Ways & Means” for integrating economic and ecological factors into a product, process practice, or service. This definition roots Sustainable Marketing in macro marketing as it seeks to encourage both producers and consumers to change their behavior and embrace Sustainable Development (Belz & Peattie, 2010). Fuller (1999) believes Sustainable Marketing must consider and account for all of the necessary planning, processing, development, implementation, and distribution of a product or a service in a manner that satisfies the following criteria: Firstly, it must satisfy customer's needs. Secondly, it must fit the organizational goals, and finally, all processes must protect the environment and be compatible with ecosystems. It is important to highlight that there is not one singular definition of sustainable marketing and that it can be open for interpretation. A literal definition of the term would mean that it is a marketing concept that enhances the ability to build long-lasting customer relationships effectively. This disregards the sustainable development agenda, which is fundamental for understanding the marketing principle (Belz & Peattie, 2010).

Therefore, it is important that we highlight that sustainable marketing elevates Green Marketing as a marketing concept as it urges everyone to consider the TBL, rather than purely focusing on the environmental issue. The marketing concept represents the evolution of modern marketing (Emery, 2012). As a concept, it seeks to blend current economic and technical perspectives with the rising trend of relationship marketing to create a foundation where the three pillars of the Sustainable Development agenda can be incorporated helping to raise awareness and encourage consumers to purchase a particular brand (Belz & Peattie, 2010). It is not necessarily a new form of marketing but rather an ‘improved’ version drawing on the existing approaches to marketing, using the strengths of each perspective, to create a marketing strategy that can endure the changing market conditions.

Societal Marketing

Societal Marketing helps incorporate three different goals: societal, organizational, and consumer. Societal Marketing's predominant focus is to ensure that there is a balance between immediate consumer satisfaction and the long-term benefits of the product or service (Fuller, 1999). A Social Classification of products (Figure 3) was created to help distinguish the different types of products in the market place helping businesses to adopt Societal Marketing. See figure 3;

Kotler (1972) believes businesses should focus on creating ‘Desirable Products’ as they do not only deliver immediate customer satisfaction but help facilitate long term consumer and societal interests. Furthermore, this strategy encourages businesses to look at all products in this way, eliminating deficient products, and to invest in salutary products so that consumers become more favorable of these products. The one restraint for this theory is that it is hard to determine what are the wants and needs of consumers and society and which methods are appropriate (Belz & Peattie, 2010).

Social Marketing

Social Marketing seeks to bridge the gap between marketing principles and social change. This means that Social Marketing seeks to provoke change amongst consumers by influencing behavior through marketing campaigns. This can apply to any form of campaign, print media, television and radio, social media, sponsorships, and online marketing. These various vehicles of Social Marketing help raise awareness for societal issues and are quite often funded by the government or non-governmental institutions to help protect society (Belz & Peattie, 2010).

Ecological Marketing

The rising Environmental Movement during the 1960s meant that consumers became increasingly aware of the pollution in our natural environment. Consumers demanded businesses and governments to be accountable for their actions, creating an environment for the establishment and rise of Ecological Marketing (Fuller, 1999). This concept sought to raise awareness for both negative and positive impacts of marketing in the Natural Environment (Belz & Peattie, 2010). Campaigns during this movement focused on the most unsustainable industries such as oil, chemicals, and cars, helping raise their awareness of their pollution. Governmental intervention would not have occurred without this marketing, and businesses would not have invested in sustainable development resulting in our atmosphere significantly more polluted today. Without Ecological Marketing, consumers would not have been aware of how damaging fossil fuels were on the environment and the importance of reducing chemical pollution in our atmosphere (Belz& Peattie, 2010). Without this concept, society would likely not pay as much attention to the realization that global warming was real.

Green Marketing

Ecological marketing was the catalyst that the environment needed to encourage consumers to be more environmentally conscious and birthed active “Green Consumers." Established in the 1980s Green Marketing’s prime aim was to sell environmentally friendly products at premium prices. Green Consumers were an active group in a society seeking more sustainable options. Green marketing attracted consumers by promoting their ecological considerations and environmental benefits of using their products over competitors (Belz & Peattie, 2010). Businesses used Life Cycle Assessments (LCA) to help quantify the environmental burdens associated with products, processes, or activities. LCA highlighted to businesses how unsustainable their packaging, products, or services were and helped them reform their unsustainable elements and promote their improvements using Green marketing techniques (Peattie, 2001). The emergence of this marketing principle meant that consumers were able to hold businesses more easily account for any environmental issues attributed to their process, product, or service. Most industries felt some form of pressure to rethink the chemical pollution they created and assessed their reliance on oil, cars, and mining to help reduce its negative impact on the environment (Belz & Peattie, 2010).

At the time, despite the changes taking place, the lack of regulation or knowledge on greener alternatives meant that brands could package themselves as a “greener” option without the research to prove it was and sold them at a premium price to ‘Green Consumers’. Often these were, in fact, a myth, with a business marketing their product as ‘green' so that could justify the enhanced price point of a ‘green’ product benefitting from an enhanced profit margin (Belz& Peattie, 2010).

A large issue attributed to the success of Green marketing, in that businesses overestimated the proportion of consumers that were actively shopping for green alternatives. This differs from Ecological marketing that expected consumers to follow and support businesses being more environmentally sustainable (Belz & Peattie, 2010). These flaws meant, for most companies, the institutional setting and price signals needed to be reformed for these marketing concepts to be successfully implemented, could not successfully adapt the theories mentioned above.

Green marketing was able to penetrate the marketing strategies of many large corporations in ways that previous macro marketing principles failed. Businesses began to embrace Green marketing as they saw that becoming more environmentally sustainable meant they were able to attract more customers and make more money by appealing to customer needs as well as traditional customer demands (Danciu, 2013). As a result, Sustainable marketing was birthed so that businesses could use their sustainable development to gain a competitive advantage over competitors through their ability to add value and satisfy consumer’s needs (Belz & Karstens, 2010).

Sustainable marketing enables businesses to plan, promote, and implement more sustainable practices in the marketplace (Fuller, 2009). This was designed to help control the development, pricing, promotion, and distribution. The success of sustainable marketing is defined by consumer reactions and perceptions of this strategy. If consumers reacted negatively to the fashion brands previous sustainability marketing, any future orientation towards sustainable development and marketing techniques could be affected (Sun et al., 2014). Therefore, it is necessary to investigate consumer attitudes and perceptions towards sustainable marketing in Fast Fashion to establish if brands are being socially responsible and encouraging consumers to re-evaluate their relationship.

Fast Fashion Industry

According to a report by the Environmental Audit Committee (2019), the textiles and garments industry is reportedly the third-largest manufacturing industry after the automotive and technology industries. In the UK, the industry contributes up to 32 billion Euros to the economy annually and has shown an increased growth rate of 1.6% higher than all the other sectors within the economy. This is especially due to the emergence of the Fast Fashion (FF) industry, which affected the multiplication of the production of garments over time. Stanton (2019) defines Fast Fashion as cheap trendy clothing that samples ideas from different cultures and inspirations and designs them into garments. It is a term used in the retail market to describe inexpensive clothing designs that are quickly produced from the design phase into stores and to consumers. This trend thereby defies the traditional way of introducing fashion lines seasonally (Stanton, 2019). The environmental audit report further outlines that FF includes increased numbers of new fashion collections every year, quick turnarounds and often, lower prices which make the cloths worthless within a short while ending up as solid waste in landfills.

Idacavage (2018) points out that in the 1960s young people began to follow trends and thus embraced cheaply made clothing creating a demand, which has grown over the years with increasing exposure due to the impact of the internet and globalization. This demand led to the innovation of the FF industry by leading fashion brands such as Zara, H$M, Primark, and a few others within the UK. The trend became more acceptable and desirable on the late 1990s and early 2000s as influencer marketing emerged due to the development of the Internet and Social media sites, which affected marketing techniques (Kenton, 2019). Individuals in celebrity status seen in these FF clothing led to a multiplied increase in their demand and led to the world easily embracing disposable fashion, which is quite impactful to the environment.

Bhardwaj and Fairhurst (2010), however, point out that the fashion apparel industry has significantly evolved particularly in the last 20 years into a Fast Fashion industry. This trend is widely attributed to the need for individuals to keep up with different fashion trends and idolized influencers. Most of the clothing is later disposed of as fast as another fashionable design hits the market as such a huge portion of the garments produced yearly end up in landfills as waste. The Environmental Audit Committee (2019) points out that less than 1% of materials used in cloth production are recycled leading to more than 300,000 tonnes of textile waste ending up in landfills or incinerated within the UK every year.

In 2018, it was revealed that the Fast Fashion (FF) Industry was the second-largest emitter of carbon dioxide in the world making the industry extremely unsustainable (Turker and Altuntas, 2014) There are many different facets, practices, and processes that make the FF industry arguably the most unsustainable industry in the world. The marketing of FF has turned to clothe from a basic human need into a disposable commodity. Since the rise of social media and E-commerce, a clear generational divide and obvious difference in mind-set towards FF have emerged, and the unsustainability of the industry has increased directly from the Millennial and Generation Z purchasing habits (Tokatli, 2007).

The lack of sustainability of the FF industry has accelerated due to globalization and the IT megatrend (Tokatli, 2007), as such, the UN General Assembly believes that the FF industry needs to implement significant sustainable development throughout their supply chains and improve on social and environmental sustainability program before engaging any trends that are cropping up in line with sustainability.

Some of these trends have accelerated the consumption of clothing by encouraging consumers to abandon traditional seasonal wardrobes through the business model of FF. The FF model centers on creating affordable on-trend clothing, using low-quality materials on a large scale in order to maximize consumer appeal by cheapening the quality and longevity of an item’s appeal and durability (Harrabin, 2019). FF brands have created a very unsustainable ‘disposable culture’ that sees clothes that are no longer in style thrown to landfill (Calderwood, 2018). This is extremely wasteful as they are not properly recycled and are left to decompose and pollute the earth further (Bhardwaj and Fairhurst, 2009). Leblanc (2019) highlights that while 100% of textile and clothing materials are recyclable the average lifetime of a piece of clothing is three years, synthetic clothing, on the other hand, may take hundreds of years to decompose.

Furthermore, FF businesses have large-scale operations and uncontrollable supply chains in developing countries. The exploitation of cheap labor, along with the lack of health and safety legislation, helps maximize their ability to generate a profit (Bhardwaj and Fairhurst, 2009). These conditions are not obvious to consumers and are very unsustainable and unethical practices (Tokatli, 2007). FF brands have pushed the agenda so that consumers must stay on trend through their adverts and sponsored influencer posts. Consumers are encouraged to panic buy clothes before they sell out by creating ‘exclusive’ collections or by advertising low stock to push consumers to purchase (Turker and Altuntas, 2014). In addition, social media pressure has led to users not posting or wearing an outfit more than once on social media leading to the normalization of this behavior through "outfit of the day” (OOTD) culture. This, in turn, had led to consumers feeling enhanced pressure to care for their appearance and stay on trend, resulting in purchasing more clothes and disposing of unwanted clothes faster more than ever before (Hill & Lee, 2015).

Millennials and Generation Z, whilst more passionate than any other generation about improving sustainability and who are actively pressurizing other industries to reform their practices, appear to show little attention to how unsustainable the FF Industry is (Turker and Altuntas, 2014). This highlights the importance of investigating whether these consumers who are more likely to purchase sustainable alternatives in other industries, are receptive to the Sustainable marketing of the FF industry and are aware of the multiple ways they are contributing to an unethical industry.

Whilst studies have shown millennials purchasing habits in the FF industry defy the trend of sustainability, in other industries such as the beauty industry, consumers have willingly embraced, demanded and shifted to more sustainable, environmentally friendly, animal-friendly, human rights-concerned, and vegan beauty products (Sumner, 2017). Santi (2019) points out that ethical fashion consumption is impossible, given the various variables that determine consumption in the FF market. She highlights that purchase decision in the FF industry are more likely to be influenced by pleasure and excitement as opposed to rational judgments about the best outcome in terms of cost and benefits for them and the environment. The marketing for FF industry, which is more rampant in the current digital environment through social media as well as adverts on YouTube and other Google sites, influences the impulse buying of FF products by consumers (Sumner, 2017).

Whilst FF brands such as M&S, H&M & Zara have begun to implement sustainable marketing to encourage consumers to make wiser choices when buying clothes, they have received little publicity or attention as they have failed to penetrate the current advertising techniques of the FF Industry (Turker and Altuntas, 2014). One of the critical issues with the sustainability of the fashion industry lies with the supply chain management (Hill & Lee, 2015). Over the past few decades, as pointed out by Mefford (2010), Lean management and IT systems such as “Quick Response” have transformed operations helping improve the sustainability of FF manufacturing. Quick Response is a strategy that matches supply with uncertain demand, controlling production and wastage, resulting in more accurate forecasting and a more sustainable supply chain. Short lead times are possible through sophisticated information or enterprise resource planning IT systems, which organize and monitors stock inventory and replenishment (Cachon & Swinney, 2011). According to Cachon and Swinney (2011), these strategies help tailor supply-demand thus avoiding wasteful production and ultimately limits the number of clothes that either ends up reduced at the end of the season or in a landfill. These brands have considerably reduced their wastage, but fast fashion global supply chains are still predominantly unsustainable due to the pollution from the production of raw materials, manufacturing, shipping, and delivery to consumers and are, therefore, are in need of significant development (Li et al., 2013).

Sustainability Marketing in FF Industry

Sustainable marketing was first used in the FF industry towards the end of the 20th century (Mefford, 2010). Brands first adopted this technique after the industry was exposed for exploiting developing countries and breaching human rights through child labor, modern-day slave labor, and poor working conditions. Nike, for instance, is one of the major brands that have adopted and put sustainability at the forefront of their marketing strategies. Eventige (2018) highlights that Nike has gone beyond CSR to outline and include its endeavors in their marketing by putting its customer's interest first and engaging in the protection and conservation of the environment.

Primark, on the other hand, is among the companies that have not quite effectively involved itself in highlighting some of the marketing practices related to sustainability. Hendriksz (2017) highlights that due to the collapse of Rana Plaza, a building in Bangladesh housing suppliers to Primark, Consumers were alerted about the unethical practices when media scandals exposed them and were only then able to hold brands accountable for their behavior through using their purchasing power. These scandals made brands realize they had a duty to be socially responsible, for both themselves and consumers, resulting in loss of consumer trust and loyalty (De Bito et al., 2008). Dach & Allmendinger (2014) hold that this also threatens the economic sustainability of these brands was threatened. In an attempt to repair their reputation, brands responded to consumer dissatisfaction attempting to repair their reputation by improving its factory conditions and its communication channels with supply chains. As a result, their brand was marketed as sweatshop-free or fair-trade, highlighting their newly found social responsibility. This also helped to raise awareness that the issue still exists in the industry (Mefford, 2010). Due to their supply chain complexity, it is difficult to track how successful these developments actually are or hold them accountable for their actions (Emery, 2012).

The emergence of Sustainable Marketing in the Fast Fashion Industry

Incorporating sustainability into FF is a challenging concept as it currently contradicts the principles of the existing business model. However, they are compatible, and if you reframe the overall objectives of a business, to incorporate stakeholders, they can be compatible (Harrabin, 2018). Not only do stakeholders need to be considered, but the planet too, if the FF industry is to become sustainable, and therefore, the sustainable fashion system as seen above is usual for businesses to reframe there priorities and goals when seeking to improve their business model ( Ninimaki, 2013).

Davis-Peccoud and Seemann (2018) elaborate that enhancing the sustainability of business normally entails the business or organization envisioning their visions in a truly sustainable economy and then drawing their missions and objectives to fit the vision. Through influencing sustainability right from the company’s vision, all the tasks and activities within the organization are designed for sustainability, and as such, the organization can shift effectively to be sustainable. In addition, advanced technology can also be included in the implementation of sustainability efforts within a business or organization.

Whilst the majority of FF brands continue to ignore the importance of being sustainable and fail to appeal to environmentally and socially conscious consumers, sustainable fashion collections and sustainable fashion brands have emerged (Niinimäki, 2013). Predominantly packaged as "Eco-Fashion," "Fair-trade Fashion," "Slow Fashion," or "Ethical Fashion" has emerged as an alternative to fast fashion collections as they are produced in line with ethical standards and manufactured by brands taking more responsibility for their actions.

They are also produced with minimal environmental impact and using recycled, organic, or biodegradable materials (Solér, 2015). Depending on the morals and objectives of a fashion brand, these sustainable clothes are promoted in very different ways and often receive no marketing at all (Solér, 2015). FF brands incorporating sustainable collections can be perceived as "greenwashing," which means that they make misleading claims or market the product in a deceptive manner so that they can reap the financial benefits of perceived sustainability. This means they must straddle the line between promoting sustainability genuinely or run the risk of being accused of “ jumping on the bandwagon” and using the trend of sustainability, simply as a tactic to generate enhanced revenue (Ninimaki, 2013).

References

- Atik, D., &Fırat, A. F. (2013). Fashion creation and diffusion: The institution of marketing. Journal of Marketing Management, 29(7-8), 836-860.

- Ahuja, N. (2015). Effect of Branding On Consumer Buying Behaviour: A Study in Relation to Fashion Industry. International Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Sciences, 3(2), 32-37

- Belz, F., and Peattie, K. (2010). Sustainability marketing. Chichester: Wiley. Domains. Journal of Consumer Research, 34, 121–134.

- Bhardwaj, V., &Fairhurst, A. (2010). Fast fashion: response to changes in the fashion industry. The international review of retail, distribution, and consumer research, 20(1), 165-173.

- Bly, S., Gwozdz, W., and Reisch, L. (2015). Exit from the high street: an exploratory study of sustainable fashion consumption pioneers. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 39(2), pp.125-135.

- Bryman, A., and Bell, E. (2011). Business research methods. Oxford : Oxford University Press

- Carrigan, M. & Attalla, A. (2001) The myth of the ethical consumer–do ethics matter in purchase behavior? Journal of Consumer Marketing, 18, 560–577.

- Cachon, G.P., and Swinney, R., 2011. The value of fast fashion: Quick response, enhanced design, and strategic consumer behavior. Management Science, 57(4), pp.778-795.

- Calderwood, I. (2019). Britain's Fast Fashion Industry Could Be Set for a Makeover. [online] Global Citizen. Available at: https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/fast-fashion-environment-uk-audit-committee/ [Accessed 14 Aug. 2019].

- Davis-Peccoud, J., and Seemann, A. (2018). Transforming Business for a Sustainable Economy. [online] Bain. Available at: https://www.bain.com/insights/transforming-business-for-a-sustainable-economy/ [Accessed 14 Aug. 2019].

- Diddi, S., Yan, R.N., Bloodhart, B., Bajtelsmit, V., and McShane, K. (2019). Exploring young adult consumers' sustainable clothing consumption intention-behavior gap: A Behavioral Reasoning Theory perspective. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 18, pp.200-209.

- De Brito, M. P., Carbone, V., &Blanquart, C. M. (2008). Towards a sustainable fashion retail supply chain in Europe: Organisation and performance. International journal of production economics, 114(2), 534-553.

- Environmental Audit Committee (2019). [online] Publications.parliament.uk. Available at: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmenvaud/1952/1952.pdf [Accessed 14 Aug. 2019].

- Evans, S and Peirson-Smith, A. (2017). Fashioning Green Words and Eco Language: An Examination of the User Perception Gap for Fashion Brands Promoting Sustainable Practices. Fashion Practice, 9(3), pp.373-397.

- Eventige (2018). Nike’s Marketing Approach with Sustainability Efforts. [online] Eventige.com. Available at: https://www.eventige.com/blog/nike-sustainability-efforts [Accessed 14 Aug. 2019].

- Fashion's Dirty Secrets. (2018). [video] Directed by S. Dooley. UK: BBC3.

- McNeill, L., and Moore, R. (2015). Sustainable fashion consumption and the fast-fashion conundrum: fashionable consumers and attitudes to sustainability in clothing choice. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 39(3), pp.212-222.

- Mefford, R. N. (2010). Offshoring, lean production, and a sustainable global supply chain. European Journal of International Management, 4(3), 303-315.

- Morgan, L., and Birtwistle, G. (2009). An investigation of young fashion consumers' disposal habits. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 33(2), pp.190-198.

- Myers, M. D. (2009) Qualitative research in business and management. Los Angeles ; London : SAGE,

- Murray, J.B. (2002) The politics of consumption: a re-inquiry on Thompson and Haytko’s (1997)“Speaking of Fashion.” Journal of Consumer Research, 29, 427–440

- Neal, B. (2018). The One Thing You Do Every Day That’s Messing With Your Budget, According To A New Survey. [online] Bustle. Available at: https://www.bustle.com/p/social-media-makes-you-spend-more-money-a-new-survey-shows-but-that-doesnt-mean-its-time-to-quit-12109313?fbclid=IwAR3P7uUbwv1I39Q6vBDNCsyu37Yr20Nfx7z81HyOVHBh6reGXDBJpT9ZgO4 [Accessed 11 Apr. 2019].

- Purvis, B., Mao, Y. and Robinson, D. (2018). Three pillars of sustainability: in search of conceptual origins. Sustainability Science, 14(3), pp.681-695.

- Razorfish (2015). Digital Dopamine: 2015 Global marketing report.

- Riera, M., &Iborra, M. (2017). Corporate social irresponsibility: review and conceptual boundaries. European Journal of Management and Business Economics, 26(2), 146-162.

- Ritch, E. L. (2015). Consumers interpreting sustainability: moving beyond food to fashion. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 43(12), 1162-1181.

- Santi, A. (2019). Sustainability in fast-fashion: will it ever be possible?. [online] Raconteur. Available at: https://www.raconteur.net/retail/fast-fashion-sustainability [Accessed 14 Aug. 2019].

- Sumner, M. (2017). It may not be possible to slow down fast fashion – so can the industry ever be sustainable?. [online] The Conversation. Available at: http://theconversation.com/it-may-not-be-possible-to-slow-down-fast-fashion-so-can-the-industry-ever-be-sustainable-82168 [Accessed 14 Aug. 2019].

- Sundström, M., Hjelm-Lidholm, S., & Radon, A. (2019). Clicking the boredom away–Exploring impulse fashion buying behavior online. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 47, 150-156.

- Subject Money, (2013). Gantt Chart Excel Tutorial. [video] Available at:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-oD50HSBBBI

- Watson, Z, M., and Yan, R. (2013). An exploratory study of the decision processes of fast versus slow fashion consumers. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 17(2), pp.141-159.

- Saunders, M. N. K., Lewis, P., and Thornhill, A. (2016). Research methods for business students. New York : Pearson Education

- Solér, C., Baeza, J., &Svärd, C. (2015). Construction of silence on issues of sustainability through branding in the fashion market. Journal of Marketing Management, 31(1-2), 219-246.

- TFL (2018). Why Aren't More Millennials Shopping Sustainably? Look at the Price Tag. [online] The Fashion Law. Available at: http://www.thefashionlaw.com/home/why-arent-millennials-shopping-sustainably-look-at-the-price-tag [Accessed 10 Apr. 2019].

- Thompson, C., and Haytko, D. (1997). Speaking of Fashion: Consumers' Uses of Fashion Discourses and the Appropriation of Countervailing Cultural Meanings. Journal of Consumer Research, 24(1), pp.15-42.

- Yin, R. K. (2015). Qualitative research from start to finish. Guilford Publications.

Looking for further insights on A Fundamental Unit Of The Brain And Its Functional Mechanisms? Click here.

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts