The Genesis And Development of The European

Origin of EU law

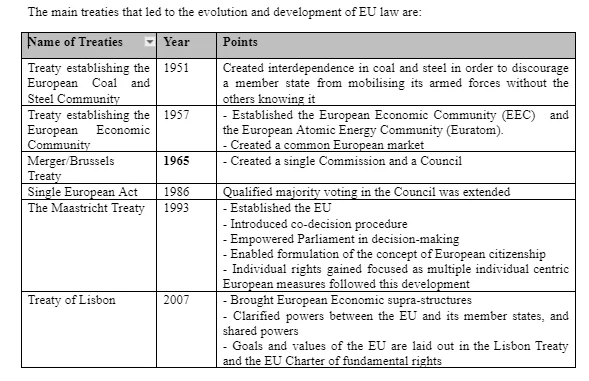

Without referring to the post war Europe where Europe was in the midst of economic devastation caused by the Second World War, tracing the origin of the EU and its laws will not be possible. There was no acute harmony among the European countries; however, this period was termed the “Golden Age of European economic growth” by economists, due to the integration steps being undertaken. Before the complete integration of EU, it was the Community law that involved the applicability of the international law. In due course, there was an intensified integration process of the community, which highlights the importance of law dissertation help in understanding these developments. Steps taken required the member to make treaties whereby members delegated their powers to the Community. Multiple steps were undertaken that resulted to European integration. The European Union (EU) was set up to end frequent wars between neighbours. A summary of the development of EU and EU laws is shown below:

EU treaties and the institution of EU law

From the earlier discussion, it is clear that EU law stems from the historical treaties that led to the evolution of EU. EU law is divided into the following legislation: Primary legislation comprises treaties, which form the basis or ground rules for all EU action Secondary legislation includes regulations, directives and decisions. They are derived from the principles and objectives set out in the treaties.

Treaties determine EU actions and decision making process

Treaties constitute binding agreements between EU member states. They lay out EU objectives and rules for its institutions, decision making process, and its relationship with its member states.

EU activities can be categorised in three segments: The first segment comprises Treaty establishing the European Community and it covers mostly all of EU issues, including agricultural policy, single market, competition policy, economic and monetary union and environmental policy. The second segment was added following the Treaty on European Union and it includes the Common Foreign and Security Policy. The third segment was added following the Treaty on European Union and covers police cooperation and criminal law.

The EU is a unique institutional set-up. It has the following three main institutions, which produce EU policies and laws through the "Ordinary Legislative Procedure". The Commission proposes new laws, and the Parliament and Council adopt them. It is the Commission and member states that implement the new laws. The Commission ensures the application and implementation of the laws.

Decision making process across the three segments of EU activities differs from one another. The first segment is supranational, while the second and the third are mainly intergovernmental. The Commission has exclusive right of initiative across all member states, but in inter-government affairs, it shares this right with the member states. The Council takes decisions by a qualified majority concerning issues across all member states and concerning inter-government affairs, decisions need unanimity among the concerned member states for their adoption. The European Parliament can block a decision issues concerning all member states, but for inter-governmental issues, it can only advise.

EU is multi-layered and is also termed an executive federalism. The law-making process is rooted to the three features associated with this system:

Looking for further insights on Futurism And Dada Movements? Click here.

aEU is structured with interwoven competencies. Making laws falls under the supranational level and the law implementation falls in the national domain.

The Council is the meeting point for national and supranational stakeholders where negotiation, legislation and implementation. c Irrespective of the applicability of majority rule, the Council follows consensus method of EU. This method goes through negotiations, compromise, and inclusion of as many parties as possible. Thus, it could be stated that the formal method of majority rule is backed by an informal consensus method. d EU institutions are intertwined when it comes to using powers, but there is a clear demarcation between them in terms of election, source of legitimacy and personal. The Council acts as the core institute of the EU federal system ensuring unity of the EU bodies. It makes the EU laws and exercises strong influence on appointment of Commission and impedes unitary parliamentary system with a close fusion between the Commission and the EU Parliament.

EU Parliament is a controlling parliament whereby it employs negative and controlling powers rather than an autonomously creating one. It has similar features to that of the working parliament whereby its character and power are separated from the government and it operates as a counter-weight to the government. It has considerably increased its influence in areas such as its power to approve or veto a new Commission or its president. However, the Council impedes the power of the Parliament due to its role in appointing the Commission. It is also a central partner of the Commission in making laws and executive functions. The greater influence of the Parliament is also deterred by the way it conducts its approval procedure of a new Commission. There is no majority rule followed and it just acts as a critical counter weight rather than support the Commission. It cannot autonomously elect and control the Commission.

The European Parliament has different level of influence according to the issues it tackles. The most common decision-making procedures are described below.

Co-decision – This process empowers the European Parliament to influence the content of decisions, such as those related to the single market, the environment, transport policy, and issues relating to food and consumer policy. In a likely change to proposal from the Commission, the Parliament and the Council of Ministers must arrive at a consensus. b Consultation – The Parliament exercises the least power in influencing decisions, such as those including agricultural policy, trade with countries outside the EU, and issues relating to police cooperation and criminal law. It just acts as a consultative body to the Council. c Assent – The Parliament give its assent to the Council for entering into association agreements with new countries.

EU Sovereignty

Austin was the founder of Monist Sovereignty, which calls for rule of power in one authority. Such sovereignty embraces the existence of a power that is absolute illimitable, determinate, inalienable, permanent and indivisible all-comprehensive. In relevance to EU law, this part of the paper will determine any difficulties in applying certain standard positions of Austin’s sovereignty theory; whether EU is sovereign and if it is, how it affects member states’ sovereignty. Conducting an Austinian analysis of law, the laws and policies issued by EU’s law-making organs are binding on member states and their citizens in virtue of the fact that the organs are sovereign. In close relevance is the principle of Thatcherism, propounded by the then UK Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher. The principle covers a style of governance where a great deal of power was centralised to herself frequently bypassing traditional cabinet structures. The principle promotes low inflation, small state and free markets by exercising tight control over money supply; privatisation; as well as constraints on labour movement. Her governance took the share of Neoliberalism where there is minimal governance and individual values are promoted and state dependency is reduced. There is reduction of government power in private sector as well as removal of regulation on private companies.

But it is not sensible enough to treat all the organs of a state or even the EU as one sovereign unit. Furthermore, member states may find it unacceptable and implausible as well. Member states defer to EU decision on a limited range of issues and their citizens obey such decision as obedience to their respective governments. Therefore, there should be a position against a limited one-state or Community-only perspective. There has to be certain recognition rendered on the rules, and a set of criteria for validity of law. Treaties such as the Paris and Rome Treaties, treaties of accession and other subsequent amending treaties provide the highest order of valid rules and principles. Even more treaties such as the European Convention on Human Rights have set standards obligatory upon member states. Valid rules also come from EU organs and their regulations, decisions and directives. However, it should also be noted that the content may differ from or overlap with member states’ criteria of validity. Therefore, an alternative approach should be a system-oriented approach that focuses in normative system law, which allows overlap of different systems without any subordination or hierarchy.

The system-oriented approach is based on the work of Hans Kelsen, where there are principles of international law under which member states’ legal system that effectively controls the territory is valid quoud international law. Member states’ laws and international law constitute a single global normative order. This is refuted by Hartian in that this single normative order is unlikely to be accepted from member states’ perspective and that international norms are deemed binding to the extent they are constitutionally authorised internally. Further criticisms are proposed by legal scholars in that the idea of system is manifestation of and contributor to false consciousness. It legitimises decisions as if they were already determined within the ‘system instead of choices made by actual decision-makers. In all conclusion, compulsion may not be imposed on EU being sovereign or on its relationship with member states as hierarchical and subordination.

EU Supremacy This doctrine of supremacy is

This doctrine of supremacy is embedded in Declaration 17 of the Lisbon Treaty. The supremacy of EU law is based on settled case laws of and the conditions set forth therein by the European Court of Justice (ECJ). EU law holds primacy over domestic laws. In Flaminio Costa v Ene [1964] ECR 585 (6/64) the supremacy doctrine was established with ECJ emphasising on making EU law efficient, independent and uniformly applicable across member states.

According to misfit hypothesis, member states may deter compliance to EU law, which is found not favourable. The event of any huge gap between the EU law and national policy may also make it increasingly difficulty in adapting EU law into national legislation. In this context, it finds relevance to discuss about Direct Effect doctrine, which was developed by ECJ in the case of Van Gend en Loos [1963] ECJ, Case 26/62. Union citizens are empowered to enforce treaty obligation against states and further that national legal systems should give effect to EU law. For a provision to be directly effective, it should be clear and precise; unconditional; and produce individual rights. Article 288 of TFEU provides that member states have the discretion to select the choice and form of applying EU law or regulations. According to Monism, EU law is directly applied and adjudicated and it does not need to be adopted or translated as a part of the national law. According to Dualism, the incorporation of EU law is not direct wherein domestic courts can only apply EU law after it is translated in domestic legislation. However, the core responsibility falls on the national court. EU law will be breached if national courts inconsistently interpret domestic law so as to avoid implementing EU law. But again national courts decide most of the EU law cases without using a preliminary reference. This gives national courts discretion and limits role of ECJ.

The supremacy of EU law is enforced by a combination of national and EU approaches. For instance, there has been an increase reference of Charter of Fundamental Rights in ECJ cases since 2010. Same is the case with national courts increasing reference to it, for example is the reference of Article 17 that deals with right to property; or Article 7 on right to private and family rights. Another approach is the Treaty Conventions. For instance, TFEU ensures EU laws are effective. Its Article 267 empowers ECJ to Justice to provide preliminary rulings concerning treaty interpretation and validity of acts of EU authorities. However, there may be diverse application of EU law when the interpretation or application is left to the national court. In Foto Frost v HZA Lubeck Ost (Case 314/85), the court noted that Article 267 ensures national courts uniformly apply EL law when an EU law was called into question. This however leaves the discretion to national courts and has the potential of divergence application and interpretation of EU law thereby bringing uncertainty of EU law. This is creates ambiguity in regard to the role play by national court decisions, which also becomes a subsidiary means to determine international law. The national courts may shield from non-favourable EU interferences. Another tool to enforce compliance of EU law stems from the role played by the European Commission. Besides the national courts’ references, it can also raise proceedings can to concerning validity of EU acts. Under Articles 258 to 281 of TFEU, ECJ can adjudicate on such proceedings. The concerned power of the Commission is provided under Articles 244 to 250 of TFEU. Through infraction proceedings, it monitors and enforces EU law compliance. Article 258 empowers the Commission to provide reasoned opinion in case a member state fails to perform Treaty obligations. In case of non-compliance, it can refer the case to ECJ.

Given all the circumstances, it must be noted that EU law and national law are different and that EU law supersedes national law.

Until ECJ began developing doctrine of direct effect, EU did not have any means for private enforcement of the EU law. It further led to Indirect Effect and States Liability. The application of the three doctrines means that ECJ oversees national courts in determining whether national courts consider directly effectiveness of EU law and whether they apply applying direct or indirect effect doctrine.

The case of Van Gend en Loos v Nederlandse Administratie der Belastingen (1963) Case 26/ 62 laid down the doctrine of direct effect, according to which a provision of the EU law can be invoked before the national courts. The case of Costa v Enel, further elaborated on this doctrine by maintaining the supremacy of the EU law over national laws.

Direct Effect enables EU law to confer rights on the individuals enforceable in national courts. This does not mean that direct effect is applicable in all cases as was seen in the Criminal Proceedings against Wijsenbeel Case C-378/97 (1999) where ECJ did not prescribe direct effect of Article 21, TFEU. This doctrine entitles individuals to rely on treaty and secondary legislation provisions. In due course, the doctrine expanded to include application to regulations and decisions of the European courts.

Expanding ECJ powers, the doctrine of indirect effect is also a means for national courts’ harmonious interpretation between national laws and EU Directives. Thus ECJ held in Colson v Land Nordrhein-Westfalen (1984) Case 14/83 that domestic courts are responsible for ensuring fulfilment of Community obligations. This finds support in Article 4(3), TFEU that provides for full implementation of EU law. This responsibility to implement EU law causes indirect effect of the EU law, including directives, even where national law predates the directives.

In addition to the doctrine of direct and indirect effect where individuals can enforce EU law, the doctrine of state liability is also an important approach that entitles an individual to enforce an EU directive even where the horizontal direct effect is not permitted to enforce a claim for damages against a private party. The individual can still claim remedy against the state if the state do not apply EU directive. In Defrenne v Sabena (No 2) (1976) Case 43/75, the court held that employers shall comply with EU law, enforceable by individuals concerning their rights directly against the employer. In Francovich v Italy Case C-6&9/90 [1991] ECR I-5357, ECJ developed the principle of state liability, wherein individuals can seek damages in the event a state breaches EU law, causing loss to the individual. A member state incurs liability to pay damages to individuals and companies adversely affected by its failure to implement a directive. Such failure breach treaty obligations entitling individuals to claim damages against the state. This right is contingent on the existence of a causal link between the breach and the loss suffered by the individual. It is however to be noted that the doctrine of state liability stems not only from non-implementation of Directives, but also from retaining national legislation that contradicts EU treaty.

Internal Market, as known as the European Single Market or Common Market, thrives for four freedoms, namely, free movement of goods, capital, services, and people within EU. Article 26(2) of Treaty on the Functioning of EU (TFEU) defines internal market as comprising “an area without internal frontiers in which the free movement of goods, persons, services and capital is ensured”.

TFEU also governs free movement of individuals. For instance, Article 21 of TFEU guarantees EU citizens the right to free movement and residence with EU. Further reinforcing this right, there are Directives like Directive 2004/38/EC that provide for freedom of movement of spouse

As held in Grzelczyk v. Centre Public D'Aide Sociale D'Ottignies-Louvain-La-Neuve (Case C-184/99), nationals of the member states have the union citizenship and can enjoy same treatment in law irrespective of their nationality. An EU citizen can seek protection provided under Article 8 of European Convention of Human Right (ECHR) and freedom of movement provided under Treaty of the Functioning of European Union (TFEU). Article 8 of ECHR provides protection of right to private and family life. The privacy right covers his or her home and correspondence. In Metock v Minister for Justice, Equality and Law Reform C-127/08, the Court held that freedoms provided under ECHR would be seriously obstructed if Union Citizens are not allowed a normal life in the host Member State. According to Article 21 of TFEU, EU citizens are guaranteed the right to free movement and residence

Activism of ECJ may also pose serious threats to interest of member states. In the case of Reinhard Gebhard v Consiglio dell'Ordine degli Avvocati e Procuratori di Milano (Case C —55/ 94) [1995] ECRI – 4165, ECJ developed a doctrine of 'rule of reason’ that justifies restriction when it is non-discriminatory. This enables ECJ to interpret provision suitable for and proportionate to objective it. The main issue is that this principle cannot be applied to all the freedom of movement as for instance, there may not a common ground between the movement of persons and that of services.

Article 86 of EC provided for scrutiny of effects of public intervention by the Commission. Policies surrounding the free movement also provided for determining the structure of market governance, and tools or policies to balance competitive interest, as seen earlier. An example of market governance could be seen in the increased use of infringement actions brought by the Commission, under Article 226 EC against member states that fail to introduce market obligations under the Internal Market. European market regulations serve a key purpose to sustain confidence in the financial market. This could be seen in earlier times when new forms of governance in the form of benchmarking techniques, indicators, or scoreboards then came into play. Given the upcoming challenges of global economic competitiveness, the Commission in 2003 streamlined the existing Broad Economic Policy with Employment Guidelines in order to bring EU economic governance. EU gave focus to market governance in the need of balancing the safeguarding the neutrality of EU and interests of wider network of stakeholders. ECJ also contributes in the area of market regulation and governance. It increased the stakeholders’ judicial and procedural rights. For example, in healthcare cares, it draws on procedural notions, which provide that all acts related to the EU law applicability shall be subjected to judicial or quasi-judicial control. In Commission v Portugal Case C-367/89 [2002] ECR I-4731, para 50, ECJ held that the Portuguese law restricting acquisition of shares in a new private company without prior authorization is not justified based on economic grounds.

In this context, the provisions of TFEU that provide for liberalisation of free movement address the issue of market government. Articles 28–30 are the main provisions govern governing free movement of goods. Under Article 28, member states are prohibited from charging any import or export duties within member states. On similar lines, Article 56 of TFEU prohibits member states from putting restriction on freedom to provide services within the Union. Though the EU law provides for free movement, there are negative impacts associated with such creation of internal market. ECJ further held that articles under TFEU, for instance Article 36, allowing member states to impose import restriction go against national interest. It held that TFEU do not take unique needs and demands of members into consideration. Furthermore, there are other provisions of TFEU that deter national interests. For instance, Article 28 to 30 provides for standardizing inter-state customs regulations and for giving equivalent effect to existing customs duties or charges. This makes foreign goods costlier than domestic goods.

As discussed herein, it could be seen that EU law actively shapes markets as it balances purposes and goals of market liberalization and regulation and furthermore strengthen market compliance. It creates and maintains a new legal order that acts as a preserver and corrector of the EU market.

In regard to the process of legislation and decision making, the principles of conferral, proportionality and subsidiarity come into play, which basically indicates non-involvement of EU in areas outside its concern. Article 5 of TFEU provides the limit of EU competences is governed by the principle of conferral. But the use of such competences is governed by the principles of subsidiarity and proportionality. Article 5(3) of the Treaty on European Union (TEU) and Protocol (No 2) apply to the application of proportionality and subsidiarity principles.

Under the principle of conferral, EU shall act only within the limits of competences as conferred upon it in the Treaties by member states. In areas where EU does not have exclusive competence, the principle of subsidiarity aims to safeguard ability of member states to take decisions and action, as well as authorises EU intervention when they cannot sufficiently achieve objectives with the reason that they could be achieved at EU level. Treaties also include reference to the subsidiarity principle for ensuring that powers are exercised as close to the citizen as possible. Under the principle of proportionality, the content and form of EU action shall not exceed than what is necessary to achieve Treaties’ objectives

Both forms are defined in the secondary law of the European Union. Equality Directives such as Council Directive 2000/43/EC; Council Directive 2000/78/EC of 27 November 2000; or Council Directive 2004/113/EC of 13 December 2004 cover the two forms of discrimination.

“where one person is treated less favourably than another is, has been or would be treated in a comparable situation, on the basis of any of the prohibited grounds such as sex, racial or ethnic origin, religion, disability, age or sexual orientation.” The effect covers a whole group of people and thus causation is a decisive element. EU regulations and ECJ case-laws provide a list of exceptions to the prohibition of direct discrimination, which is a closed one and is predicted in the binding law. But, the exception does not remain the same in regard to all criteria of discrimination. For example, according to article 14 (2) of Directive 2006/54, direct discrimination based on sex is justifiable by “a genuine and determining occupational requirement, provided that its objective is legitimate and the requirement is proportionate”

Indirect discrimination takes place: “where an apparently neutral provision, criterion or practice would put persons protected by the general prohibition of discrimination at a particular disadvantage compared with other persons unless that provision, criterion or practice is objectively justified by a legitimate aim and the means of achieving that aim are appropriate and necessary.” The effect such a measure is similar to direct discrimination and covers individuals who belong to the protected group. Indirect discrimination is an effect-related concept. Possible justifications for indirect discrimination are formulated in general terms based on acceptable, legitimate aims and not on purely economic nature and measures taken in order to achieve them shall be proportional.

Continue your journey with our comprehensive guide to The Federal Court Role In International.

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts