Advancements in Treatment for Leaking Blood Vessels in Wet Age-Related Macular Degeneration

Introduction

Until recently, laser treatment was the only available cure for treatment of leaking blood vessels related to wet age-related macular degeneration (AMD). According to Ghazi et al. (2010), wet AMD is a leading cause of vision loss in elderly people – 60 years and beyond – which affects millions of people worldwide. Laser photocoagulation was the earliest treatment for AMD. Numerous clinical trials led to the development of other treatments such as photodynamic therapy with Visudyne which also relied on laser to administer treatment (Kim, 2006). For those researching this area, healthcare dissertation help can provide valuable support in understanding these complex developments. The major limitation of laser treatment is the high likelihood of recurrence of leakage in two years’ time (Chen, et al., 2007). Dejneka et al. (2008) observes that laser therapies were risky since they led to scarring of the macula which contributed to additional vision loss.

Recent advancements in medical technology have led to development of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) antagonists for AMD therapy. Stevenson et al. (2012) reports that VEGF is a powerful endothelial cell mitogen that arouses proliferation, tube formation and migration which is the leading cause of angiogenic growth of new blood vessels. According to Tufail et al. (2010), the discovery of VEGF antagonists introduced a novel treatment regimen characterised by long-term and better results. The first VEGF antagonist was Pegaptanib which was an aptamer developed to bind to VEGF specifically (Schouten, et al., 2009). The drug proved that VEGF is the main angiogenic factor in choroidal neovascularization (CNV). Avanstin and Lucentis were developed later as VEGF antagonists. Avastin is the trade name for Bevacizumab while Lucentis is the trade name for Ranibizumab. According to Landa et al. (2009), both Avastin and Lucentis were developed as anti-angiogenic drugs and have nearly similar chemical biochemical structures. Kent et al. (2012) report that Lucentis is a recombinant humanised monoclonal antibody bit that is specially designed for intraocular use. As such, it binds to VEGF-A, and inhibits its biologic activity. Similarly, Avastin is a recombinant humanised monoclonal antibody which acts in a similar manner as Lucentis by blocking angiogenesis through inhibition of biologic activity of VEGF-A (Abraham, et al., 2006; Chen, et al., 2007; Shah & Priore, 2009). It is evident that both drugs act at the same receptor level – VEGF-A (Garg, et al., 2008; Kent, et al., 2012). As mentioned earlier, their chemical structures are nearly alike except in the end-ligand.

Both Avastin and Lucentis are manufactured by Genentech in the United States. Both drugs are licenced and proved by FDA but Avastin is used off-label in AMD therapy (Tufail, et al., 2010). As such, Avastin is licenced for treatment of colon cancer while Lucentis is used in treatment of AMD (Chen, et al., 2007; Wu & Sadda, 2008). The latter was approved after two major studies revealed that it had a stabilising and beneficial effects to more than 30 percent of a study population (Wu, et al., 2008). However, the Lucentis is highly priced as compared to Avastin which is the main reason why the latter is used off-label in AMD therapy.

Garba and Mousa (2010) report that wet/exudative/neovascular AMD entails abnormal development of blood vessels under the macula which break, bleed and leak fluid. As a result, the macula is damaged and if not treated, it may lead to severe and rapid loss of central vision. Wet AMD’s prevalence ranges from 10 – 20 percent. According to Kent et al. (2012), there are two types of macular degeneration namely wet and dry. Dry/type one/atrophic AMD is the most prevalent – 85 – 90 percent. It involves degeneration of the retinal pigment epithelial cells (RPE) with formation of drusen – small yellow deposits which leads to drying out and thinning of the macula causing it to lose its function.

The aim of this review is to provide an in-depth and evidence-based analysis of the most recent clinical findings regarding the effectiveness of Lucentis and Avastin in wet AMD therapy to determine which the best is. AMD treatment is has attracted considerable interest from researchers and both drugs have been involved in numerous trials to evaluate their effectiveness. This review is a part of the general interest and it is important in exploring whether the huge difference in the cost of the two drugs has any bearings in the safety and effectiveness during treatment in the wake of financial restrictions facing the NHS. Although Avastin is not clinically proven and licensed for wet AMD therapy, numerous epidemiologic surveys have revealed that it has beneficial effects.

Method

This review identified and used articles relating to empirical trials of Lucentis and Avastin published in peer-reviewed journals. As such, a computerised multistage systematic approach was employed to filter through the PubMed database (National Library of Medicine) for articles published from 2000 up to December 2016. A strict identification and vetting regime was used to ensure that the chosen articles met the admissibility criteria. The search and identification of the articles was accomplished in three stages as follows: A broad computerised search was initially done to identify relevant articles using the terms “AMD”, “Avastin” and “Lucentis”. In the second stage, relevant abstracts under the refined search criteria including ‘treatment of wet AMD,’ ‘Lucentis vs Avastin,’ ‘Lucentis clinical use’, ‘Avastin clinical use’ and ‘clinical studies on Lucentis and Avastin’ were read. In the third stage, full articles were read, with those showing clinical studies on the use of Lucentis and Avastin for the treatment of Wet AMD chosen to be included in the elective.

Inclusion criteria

Each individual search produced tens or hundreds of citations that were reviewed for topical relevance and applicability in this project. Articles were included if they narrated issues related to empirical evidence on the effectiveness of either or both drugs.

Exclusion criteria

Articles published before 2000 were excluded to pave room for inclusion of new evidence in treatment of wet AMD. Additionally, reviews were also excluded to avoid reporter bias.

Results

For each drug, the evidence of its effectiveness has been presented as either clinical or epidemiological data.

Effectiveness of Avastin and Lucentis

The period in which the either of the drugs take to neutralise VEGF-A and the period throughout which they keep it neutralised is an important concept in evaluating the effectiveness of the drugs (Klettner & Roider, 2008; Dejneka, et al., 2008). Additionally, the volume of drug and the concentration are reliable indicator of the effectiveness.

Epidemiological findings

At clinical doses both Avastin and Lucentis are equally potent in neutralisation of VEGF (Klettner & Roider, 2008). A fraction of clinical doses of both drugs has been found to neutralise the VEGF completely. Some studies have shown that Lucentis is more efficient at neutralising VEGF when in dilute condition (Chang, et al., 2007). A direct effect of Lucentis and Avastin on VEGF protein expression has indicated additional pathways of VEGF inhibitors. Klettner and Roider (2008) sought to determine the maximum period in which Avastin and Lucentis are effective in neutralising VEGF. They found that both antagonists were effective in defusing VEGF up to 16 hours after each application. The effects were reportedly similar. In a similar experiment, Wu and Zadda (2008) found that after 14 hours of perfusion, concentrations of Lucentis and Avastin were 6ng/ml and 12ng/ml respectively.

Lucentis and Avastin are highly efficient in defusing VEGF and it has been found that they neutralise the compound completely when used in clinical concentrations (Wu, et al., 2008). When in diluted form, both substances increase their potency but Lucentis has been found to be more effective than Avastin. Several researchers (Chang, et al., 2007; Wu, et al., 2008; Subramanian, et al., 2010) have established the threshold FOR Avastin at which VEGF is detectable in considerable amounts is one microgram per millilitre. VEGF amount is considered significant if it is found in amounts larger than 50 pentagrams per millilitre of blood and eye fluids (Garba & Mousa, 2010). When Lucentis is used, the threshold is 60 nanograms per millilitre below which VEGF is detectable in significantly higher amounts greater than 100 pentagrams per millilitre.

Several studies have showed no difference in efficiency between Avastin and Lucentis when presented in clinical concentrations and doses. According to Subramanian et al. (2009), their natures as antibody and antibody fragment of a similar murine precursor can explain the observation. Several researchers ( (Garg, et al., 2008; Wu, et al., 2008) have established that Lucentis is more effective than Avastin when it is highly diluted. As mentioned earlier, Avastin is effective up to a concentration of one microgram per millilitre of eye fluids which indicates that Lucentis has a significantly higher binding capacity than Avastin. Published observations show that on a molar basis, a six-fold higher affinity in binding can be achieved.

Reports of early outcomes of double-masked, prospective and controlled trials comparing Avastin and Lucentis have shown insignificant differences in the effectiveness of the two wet AMD therapeutic components. Subramanian et al. (2010) assessed visual acuity of participants who had taken either Avastin or Lucentis. Over time, participants were presented with tomography-guided optical coherence, variable-dosing treatment schedules and the main outcomes were foveal thickness, total number of injections during the period of study and visual acuity. The average pre-operative visual acuity for the Avastin group was 34.9 letters and 32.7 letters for the Lucentis group. After a year, the mean vision for the Avastin group was 42.5 letters indicating an improvement of 17.88 percent. The mean vision for the Lucentis group was 39.0 letters indicating an improvement of 16.15 percent. Tests of significance such as two-tailed t-test failed to show any statistically significant difference between the two groups. It was concluded that both drugs are effective and it was not possible to obtain conclusive results using small sample populations.

Neovascular area (NA) was examined after administration of Lucentis and Avastin in two different sample populations. Stevenson et al. (2012) found a statistically significant decrease in NA from the start of the empirical investigation to week 3 for participants that had taken Lucentis (−39.8% ± 24.1%; P < 0.001). At the same time, it was found that NA area remained unaffected for patients that had taken Avastin until the sixth week of the study (−27.9% ± 41.2%; P=0.007). Additionally, the mean reduction in NA from the baseline was 47.5 percent at week 24 for participants treated with Avastin and 55.3 percent at week 16 for participants treated with Lucentis. As much as the reduction in NA at comparable time periods was steadily higher for the Lucentis group as compared to the Avastin group, the differences were found not to be statistically significant (Abraham, et al., 2006; Tufail, et al., 2010).

Investigation into the size of vessel calibre (VC) with both drugs has revealed interesting results. Stevenson et al. (2012) found that by week 3 participants who had taken Lucentis showed statistically significant reductions in the vessel calibre (−25.8% ± 18.8%; P = 0.001). However, it was not until week 12 when participants who had taken Avastin exhibited significant reductions in vessel calibre (−30.8% ± 41.7%; P = 0.006). At the end of the survey, it was found that the average change in VC was -59 percent for the Lucentis group and -36.2 percent for the Avastin group. Although the decrease in VC was consistently greater for participants who had taken Lucentis at comparable times, the differences did not show any statistical significance again.

Change in invasion area (IA) was also examined for both groups. The average change in IA found to be -12.3 percent at week 16 for the Lucentis group and -20 percent for Avastin group at week 24. Again, statistical calculations proved that the findings were not statistically significant when compared to each other or baseline measurements.

In their study, Stevenson et al. (2012) also assessed adverse events and additional end-points using Snellen visual acuity measurements. The Snellen measurements were converted to their LogMAR equivalents (Gaudreault, et al., 2005; Dejneka, et al., 2008; Garba & Mousa, 2010). It was found that that the Lucentis arm had a corrected LogMAR visual acuity of 0.68 ± 0.62 at baseline and 0.55 ± 0.37 at the end of the study. On the other hand, the Avastin arm has LogMAR visual acuity of 0.68 ± 0.62 at baseline and 0.55 ± 0.37 at the final week. Again, statistical calculations showed no statistical difference in visual acuity, systemic blood pressure or corneal thickness.

The study by Stevenson et al. (2012) revealed that Lucentis is more effective than Avastin in treatment of corneal neovascular area. However, intergroup comparison failed to show any statistically significant differences at the comparable time points used during the study. The effectiveness of the Lucentis drug can be attributed to it low molecular weight which allowed for more effective corneal penetration and corresponding establishment of beneficial quantities and concentrations as compared to Avastin (Stepien, et al., 2009; Ghazi, et al., 2010). Additionally, Lucentis was found to improve measured outcomes such as central retinal thickness and visual acuity better than Avantis but the differences in their capacities were not statistically significant.

Based on individual tests, several researchers (Stevenson, et al., 2012; Pece, et al., 2015) have concluded that Lucentis is superior and it is the better choice in treatment of corneal Neovascular area. However, in treatment of AMD the researchers concluded that statistical tests failed to show any statistically significant difference in changes brought about by administration of each drug. There is sufficient evidence for the effect of Lucentis on central retinal thickness and visual acuity (VA) in wet AMD. Stepien et al. (2009) found that Avastin improves the central retinal thickness and VA in patients with wet AMD.

A novel practice in the field is comparison of outcomes after switching treatment from one drug to another. Kent et al. (2012) compared central retinal thickness and VA in participants that had initially been treated with Avastin but switched to Lucentis. It was found that visual acuity improved significantly when compared to initial baseline values following a treatment course involving three or more injections of Avastin. Additionally, participants showed a further significant improvement in VA after a switch to Lucentis (Chen, et al., 2007; Subramanian, et al., 2009; Subramanian, et al., 2010). The mean central retinal thickness as measured by optical coherence tomography showed a significant reduction after a course of treatment with Avastin. Additionally, a further reduction was observed after administration of a course of Lucentis. Switching between the drugs was found to have a beneficial effect. As such, retinal thickness was found to reduce and visual acuity was found to improve with administration of Avastin which compares to Kent et al. (2012) findings. Lucentis can improve or maintain the effect achieved after an initial dosage of Avastin.

The mean LogMAR of Avastin and Lucentis groups were found to improve in a six-month follow-up study of Chinese patients. However, the changes between the two groups did not show any statistically significant difference. It was concluded that intravitreal Avastin and Lucentis have equivalent effects on the central retinal thickness and visual acuity. These findings are similar with those obtained by Kent et al. (2012); Stepien et al. (2009); Stevenson et al. (2012).

Clinical findings

Therapies for exudative and atrophic AMD require regular treatment to prevent loss of vision. Comparison of AMD Treatments Trials (CATT) was performed by Wu et al. (2008) to compare Lucentis and Avastin with as-needed and monthly treatment schedules. After two years it was found that visual acuity with monthly treatment schedule was slightly better when compared to as-needed dosages irrespective of the drug used. Both Avastin and Lucentis were found to be highly effective regardless of the dosage regimen used to administer them. In any clinical study, adverse events point out to worsening or development of a medical condition. Such events may or may not be associated with clinical trials but it is important to monitor and report them. In older population − >80 years, serious adverse events (SAEs) occurred at a rate of 40 percent for the participants that received Avastin. One-third of the patients were diagnosed with non-infectious epithelial keratitis. Five patients were diagnosed with intraocular inflammation or endophthalmitis. On the other hand, the rate was lower at 32 percent for participants that received Lucentis. Fewer doses of either drug were associated with higher rates of SAEs which is an abnormal dose-response relationship. However, CATT was unable to determine whether a relationship exists between treatments using both drugs and particular adverse events. After two years, the improvement in visual acuity of the participants was remarkable. In fact over two-thirds of the participants had a driving vision that was 20/40 and beyond.

Subramanian et al. (2009) conducted a randomised clinical trial at the Boston Veterans Affairs Healthcare System to assess the potency of Avastin and Lucentis. This was similar to another conducted a year later although it was single-centred. The mean preoperative VA was 31.6 letters in the Avastin group while that in the Lucentis group was 30.4 letters. After 6 months, the mean vision for the Avastin group was 46.4 letters and 37.4 letters in the Lucentis group. Although both drugs had aided in improvement of visual acuity, statistical significance tests failed to show any difference between the groups. Therefore, both Avantis and Lucentis are equally potent in treatment of choroid neovascularization as a basic step in treating wet AMD.

When both Lucentis and Avastin are used as additional treatments for wet AMD, research has shown that Lucentis is slightly better than Avastin if used as an additional treatment particularly for people with advanced wet AMD (Schouten, et al., 2009). Lucentis was found to reduce the number of injections required for treatment.

According to Kent (2012), several isolated cases associated with the use of Avastin render it dangerous to a minority few. For example, some people have reported high eye pressure which induces pain after injections. In late 2008, Genentech, which is the manufacturer of the drugs reported that off-label use of Avastin had led to an outbreak of a serious eye inflammation at four centres in Canada where people received eye injections for treatment of AMD.

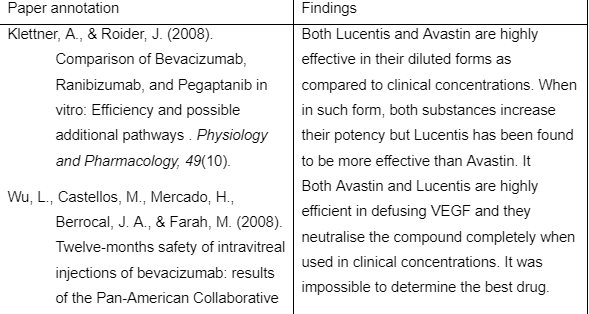

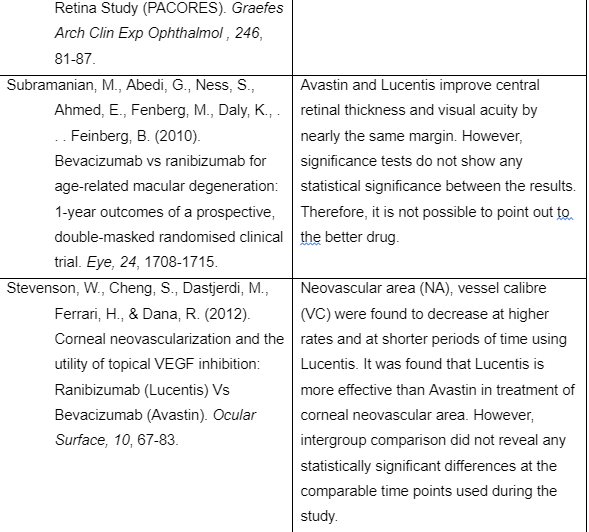

The following table summarises the details and findings of key papers used in the above review

Discussion

The reviews above indicate that there are additional pathways of VEGF suppression. Additionally, it evident that there is more complex regulation of secretion and expression of VEGF that what is known at the moment (Spaide, et al., 2006; Stevenson, et al., 2012). This may be the reason as to why most researchers have failed to obtain significant results on the differences in results brought about by Lucentis and Avastin. Therefore, there is need to modulate VEGF expression through unknown pathways including intracellular effects and internalisation to understand the protein better (Garg, et al., 2008).

During literature search, prospective randomised studies comparing Lucentis to Avastin in retinal vein occlusion were absent. While both are equally effective in treatment of individual cases such as CNV and VA, hard and conclusive data is missing.

Avastin and Lucentis are monoclonal antibodies that inhibit the biological activity of VEGF to control the exudative complications brought about by AMD. In the current review, both drugs were equally effective since no single study concluded that one was better than the other. All studies found that both drugs have inherent abilities to reduce foveal thickness and improve visual acuity. While Lucentis was found to act quicker than Avantis in considerable time points, statistical tests did not show any significant difference between the effects of the two drugs. As aforementioned the time course of response for each drug was different but the time taken to achieve significant results while using Avastin was longer as compared to Lucentis. However, the effects of Avastin are prolonged as compared to Lucentis going the amount of time taken for the outcomes to return to baseline.

The findings above suggest that intravitreal Avastin can be administered less frequently than intravitreal Lucentis in the treatment of eyes with wet AMD. Over the years, intravitreal inhibition of VEGF has become the most preferred and the most practiced therapy in exudative AMD. The molecular structure (Garg, et al., 2008; Messori, 2014) of Lucentis allows the drug penetrate the membranes quickly and establish adequate quantities and concentrations to keep off the effects of VEGF.

Avastin was found to be unfavourable for octogenarians since it was found to contribute to serious advance events (SAEs) such as intraocular inflammation and non-infectious epithelial keratitis. Avastin has a higher rate of inducing SAEs as compared to Lucentis particularly among elderly people aged 70 years and beyond.

Avantis is used off-label against which the manufacturer opposes. The main contributing factor is that the drug costs significantly less as opposed to Lucentis which is expensive (Abraham, et al., 2006; Chen, et al., 2007; Stepien, et al., 2009). A dose of Avantis can be obtained for about $50 while that of Lucentis goes for $1800 and beyond (Messori, 2014; Pece, et al., 2015). The above clinical and epidemiologic reviews have clearly failed to show any significant difference in the changes induced by administration of either drug. Therefore, Avantis and Lucentis are equally potent in wet AMD therapy. However, in line with some findings, Avantis has a slower but potent effect while Lucentis is faster owing to its molecular structure.

Critical appraisal of reviewed articles

According to Heller (2008), frequent critical appraisals of research articles by clinicians assist in providing optimal patient care and solving clinical dilemmas. Critical appraisal is a systematic process of identifying the strengths and weaknesses of research articles to examine the reliability and hence the usefulness of the research findings. In the first place, all articles used in the review had appropriate research question that matched this review’s research question. As such, they sought to determine the more effective drug between Avastin and Lucentis. Second, suitable research designs were employed to gather data. In fact, most researchers used randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in epidemiological and clinical trials. RCTs are widely recognised and used in majority of clinical and epidemiological studies. Third, all researchers stated that the major shortcomings of their studies was inadequate sample populations. This was a major fail in such instances since such results. Another researcher conducted a single-centred research which ruled out the possibility of generalising the findings. The papers reviewed did not state their potential sources of bias and how such issues were dealt with. Therefore, it was difficult to determine the credibility of the results without first addressing methodological biases and determining the extent of their influence. Lastly, concerning statistical tests, all papers used two-tailed t-tests to assess statistical significance of the results. The test is appropriate in surveys involving two head on investigations with similar anticipated results (Ghazi, et al., 2010).

In summary, this review has established that both Lucentis and Avastin are equally potent is treating wet AMD. Keeping costs aside, it would appear that Lucentis is the better drug of the two owing to some fundamental perceived qualities. For example, it has mild effects among the octogenarians as compared to Avastin whose side effects can be severe (Dejneka, et al., 2008; Garg, et al., 2008). Second, it was found to reduce the neovascular area and vessel calibre in extremely short periods as compared to Avastin which took over 3 times the time taken by Lucentis to produce similar effects (Kent, et al., 2012; Stevenson, et al., 2012). In fact, despite the extended amount of time, Avastin’s effects were quantifiably lower. In increasing visual acuity, patients that used Lucentis had had mean visions as compared to their counterparts that used Avastin (Subramanian, et al., 2009; Tufail, et al., 2010). As such, it is evident that Lucentis is the best owing to its shortness of course time and reduced SAEs among the octogenarians.

References

- Abraham, L., Cortes, F., Alvarez, G., Rojas, M., & Canton, H. Q. (2006). Intravitreal bevacizumab therapy for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: a pilot study. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Graefes Arch Clin Exp, 245, 651-655.

- Bashur, Z., Bazarbachi, A., Schakal, A., Haddad, Z., & Haibi, P. (2006). Intravitreal bevacizumab for the management of choroidal neovascularisation in age-related macular degeneration. American Journal of Ophthalmology, 142, 1-9.

- Chang, S., Bressler, M., Fine, T., Dolan, M., & Klessert, R. (2007). MARINA Study Group. Improved vision-related function after ranibizumab treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration: results of a randomized clinical trial. Archives of ophthalmology, 125(11), 1460-1469.

- Chen, Y., Wong, Y., & Heriot, J. (2007). Intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) for neovascular age-related macular degeneration: a short-term study. American Journal of Ophthalmology, 143, 510-512.

- Dejneka, S., Wan, S., Bond, S., Kornbrust, J., & Reich, J. (2008). Ocular biodistribution of bevasiranib following a single intravitreal injection to rabbit eyes. Molecular Vision, 14, 997-1005.

- Garba, O., & Mousa, A. (2010). Bevasiranib for the treatment of wet, age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology and Eye Diseases , 2, 75-83.

- Garg, S., Brod, R., Kim, D., Lane, R., Maguire, J., & Fischer, J. (2008). Retinal pigment epithelial tears after intravitreal bevacizumab injection for exudative age-related macular degeneration. Clinical Experiment Ophthalmology, 36(3), 252-256.

- Gaudreault, J., Fei, D., Rusit, J., Suboc, P., & Shiu, V. (2005). Preclinical pharmacokinetics of Ranibizumab (rhuFabV2) after a single intravitreal administration. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science , 46(2), 726-733.

- Ghazi, G., Kirk, T., Knape, R., Tiedeman, S., & Conway, P. (2010). Is monthly retreatment with intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) necessary in neovascular age-related macular degeneration? Clinical Ophthalmology, 4, 307-314.

- Heller, R. (2008). Critical appraisal for public health: a new checklist. Public Health, 122, 92-98.

- Kent, J., Iordanous, S., Mao, Y., Powell, A., Kent, M., & Sheidow, S. (2012). Comparison of outcomes after switching treatment from intravitreal bevacizumab to ranibizumab in neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Canadian Journal of Ophthalmology-Journal Canadien D Ophtalmologie, 47, 159-164.

- Kim, R. (2006). Ranibizumab versus verteporfin for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. New England Journal of Medicine, 355, 1432-1444.

- Klettner, A., & Roider, J. (2008). Comparison of Bevacizumab, Ranibizumab, and Pegaptanib in vitro: Efficiency and possible additional pathways . Physiology and Pharmacology, 49(10).

- Ladas, I., Karagiannis, D., Rouvas, A., Kotsolis, A., & Liotsou, A. (2009). Safety of repeat intravitreal injections of bevacizumab versus ranibizumab. Retina, 29, 313-318.

- Landa, G., Amde, W., & Doshi, V. (2009). Comparative study of intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) versus ranibizumab (Lucentis) in the treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmologica, 223(6), 370-375.

- Li, J., Zhang, H., Sun, P., Gu, F., & Liu, Z. (2013). Bevacizumab vs ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration in Chinese patients. International Journal of Ophthalmology, 6, 169-173.

- Messori, A. (2014). Avastin-Lucentis: off-label and surroundings. Recenti progressi in medicina, 105, 137-140.

- Michels, S., Rosenfeld, J., Puliafito, C., & Marcus, N. (2005). Systemic bevacizumab (Avastin) therapy for neovascular age-related macular degeneration twelve-week results of an uncontrolled open-label clinical study. Ophthalmology, 112, 1035-1047.

- Pece, A., Milani, P., Monteleone, C., Trombetta, C., Crecchio, J. D., Fasolino, G., . . . Vadala, M. (2015). A randomized trial of intravitreal bevacizumab vs. ranibizumab for myopic CNV. Graefes Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology, 253, 1867-1872.

- Roller, A., & Amaro, H. (2009). Intravitreal ranibizumab and bevacizumab for the treatment of nonsubfoveal choroidal neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration. Arquivos Brasileiros De Oftalmologia, 72(5), 677-681.

- Rosenfield, J., Brown, M., & Heier, S. (2006). Ranibizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. New England Journal of Medicine, 355(14), 1419-1431.

- Sassa, Y., & Hata, Y. (2010). Antiangiogenic drugs in the management of ocular diseases: Focus on antivascular endothelial growth factor. Clinical Opthalmology, 4, 275-283.

- Schmucker, C., Ehlken, C., Hansen, L., Antes, G., Agostini, H., & Lelgemann, M. (2010). Intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) vs. ranibizumab (Lucentis) for the treatment of age-related macular degeneration: a systematic review. Current Opinion in Ophthalmology, 21, 218-226.

- Schouten, J., Heij, E. L., Webers, C., Lundqvist, I., & Hendrikse, F. (2009). A systematic review on the effect of bevacizumab in exudative age-related macular degeneration. Graefes Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology, 247, 1-11.

- Shah, A., & Priore, L. (2009). Duration of action of intravitreal ranibizumab and bevacizumab in exudative AMD eyes based on macular volume measurements. British Journal of Ophthalmology, 93, 1027-1032.

- Spaide, R., Laud, K., & Fine, F. (2006). Intravitreal bevacizumab treatment of choroidal neovascularization secondary to age-related macular degeneration. Retina, 26(4), 383-390.

- Stepien, K., Rosenfield, J., & Puliafito, C. (2009). Comparison of intravitreal bevacizumab followed by ranibizumab for the treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Retina, 29(8), 1067-1073.

- Stevenson, W., Cheng, S., Dastjerdi, M., Ferrari, H., & Dana, R. (2012). Corneal neovascularization and the utility of topical VEGF inhibition: Ranibizumab (Lucentis) Vs Bevacizumab (Avastin). Ocular Surface, 10, 67-83.

- Subramanian, L., Ness, S., Abedi, G., Ahmed, E., Daly, M., Houranieh, A., . . . Nguyen, M. (2009). Bevacizumab vs ranibizumab for age-related macular degeneration: early results of a prospective double-masked, randomized clinical trial. American Journal of Ophthalmology, 148, 875-882.

- Subramanian, M., Abedi, G., Ness, S., Ahmed, E., Fenberg, M., Daly, K., . . . Feinberg, B. (2010). Bevacizumab vs ranibizumab for age-related macular degeneration: 1-year outcomes of a prospective, double-masked randomised clinical trial. Eye, 24, 1708-1715.

- Tufail, A., Patel, J., & Egan, C. (2010). Bevacizumab for neovascular age related macular degeneration (ABC Trial): multicentre randomised double masked study. BMJ, 34.

- Wu, L., Castellos, M., Mercado, H., Berrocal, J. A., & Farah, M. (2008). Twelve-months safety of intravitreal injections of bevacizumab: results of the Pan-American Collaborative Retina Study (PACORES). Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol , 246, 81-87.

- Wu, Z., & Sadda, R. (2008). Effects on the contralateral eye after intravitreal bevacizumab and ranibizumab injections: a case report. Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore, 37(7), 591-593.

Appendices

Appendix A

Title: Lucentis or Avastin, which is best?

Introduction:

- What is the difference between lucentis and avastin biochemically, licence, use?

- what is age related macular degeneration? Prevalence – difference between wet and dry? (very brief)

- The role of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)

- Very brief history on origins of lucentis and avastin

- Importance of the topic in modern times

Methods

The overview will be done from a neutral point of view summarising the most recent clinical findings in this field from peer reviewed published journals. The PubMed database (National Library of Medicine) will be used to source for appropriate journal articles. The search terms include: “AMD”, “Avastin” and “Lucentis, ‘treatment of wet AMD,’ ‘Lucentis vs Avastin,’ ‘lucentis clinical use’, ‘avastin clinical use’ and ‘clinical studies on lucentis and avastin’

Results

This section will show the number of papers obtained and those that will be used.

Discussion

This section will elaborate on the findings. It is anticipated that Avantis will be the better option of the two drugs in treatment of wet age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

Take a deeper dive into Adults Living with Autism Spectrum Disorder with our additional resources.

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts