Leadership Styles and Innovation in Iraqi NGOs

Literature Review

Overview

The main purpose of the literature review chapter is to evaluate the available body of research in order to provide a conceptual and empirical background of the investigation of the effect of leadership style in NGOs in Iraq on their innovation. A systematic approach to literature review was used in order to ensure that all available evidence relevant to this study has been included. The main research question RQof“What are the effects of leadership styles on innovation in NGOs in Iraq?” has been broken down into the following set of sub-questions:

Q1. What are the key theories of leadership and leadership styles in the context of the Middle East and Iraq?

Q2. How dointernal and external factors affect their use in NGOs?

Q3. What are the innovation theories and the main drivers of innovation in NGOs?

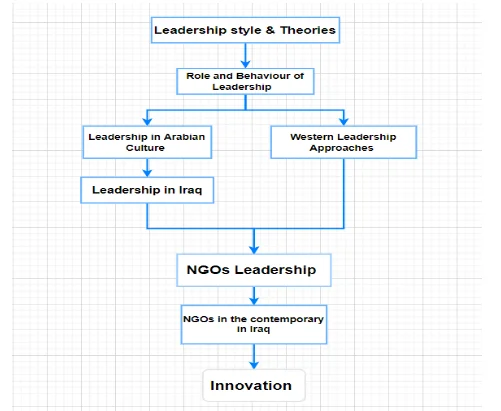

This research will explore the aspect of leadership styles and theories on innovation in NGOs in the Middle East and Iraq. The reason for this RQ and Qs is to augment our understanding of the role and behaviour of leadership in improving organisational performance through innovation in the particular context of NGOs in Iraq. This research will also enhance the understanding of the factors that shape the leadership styles under discussion. Both the internal and external factors significantly impact the application of leadership styles in NGOs in the Middle East context which in turn affect the process of innovation. The factors vary in different geographical environments due to the wide spectrum of the existing cultural differences. However, this research will place a primary emphasis on the context of the Arabian culture in the Middle East. The extent of this culture extends from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to Arabian Sea in the east and from the Mediterranean Sea. The leadership styles applied by leaders in the Arabic construct are different from the Western society due to the different in religion, tribal ethnic makeup and geographical variables (Aldulaimi, 2020). However, due to globalisation, decentralisation of culture is prevalent thus widening the possibility of the Middle Eastern culture being found in other regions. Further, this research will highlight the innovation theories which are relevant in determining the innovation pattern in NGOs in Iraq. The format of leadership in Iraq contrasts with the leadership styles and theories applied in the West due to cultural differences between the two regions. The entire literature review systematically delineates the components of the paper in relation to the research question and the three sub questions that further advance the research. The systematic presentation of the literature of the research with regard to the arrangement of the research question and the sub questions enhances an ideal understanding of the topic under discussion. There are four major sections in this chapter upon which the primary components of the paper in relation to the topic will get based. Each section is based on the main research question and the sub-questions with the main purpose of understanding the topic under search strategy.According to (Boote&Beile, 2005), a valuable and substantial research stems from a sophisticated and thorough literature review. As such, the complexity of leadership and innovation research thus requires such thorough reviews. Section 2.1, the first discussion section in this chapter, presents the leadership styles, theories and background. This section will comprehensively provide a background information on the leadership theories and styles in generally, a critique of the Western leadership theories will convey its difference with those of Iraq and the Middle East in how they neglect the history and culture of the Middle East and Iraq. Additionally, section 2.2, will comprehensively analyse leadership in the Middle East, Iraq and as used in NGOs in Iraq. A clear analysis of leadership in three spectrums will further steer an understanding on the components of leadership on innovation in NGOs in Iraq. Subsequently, section 2.3 will provide the relevant literature on the NGO sector in Iraq alongside its origins, periodic developments and its role in the contemporary society in Iraq. The understanding of the nature and operations of NGOs in Iraq concisely provides a framework to further understand leadership in relation to leadership styles and theories as used in NGOs for innovation. Section 2.4 then introduces the aspect of innovation as influenced by the leadership theories and styles in NGOs. The section starts with the evaluation of the two primary innovation theories, a critical examination of the differences between private enterprises and NGOs in terms of innovation and the specific drivers and barriers to innovation in the NGO sector. The final segment of this research will integrate every aspect of literature from the previous sections in relation to the topic for further understanding of the topic under investigation.

Leadership styles in the middle east are influenced by both the external and internal factors. External factors entail globalisation, free trade and economy, training and experiences exchange and international NGOs working around the Middle East, Iraq and the Arabic countries. Conversely, the internal factors include religion, rules and cultures. In the Middle East and Iraq, globalisation has enhanced the need to understand how cultural differences impact leadership styles considering its potential influence on organisational performance (Nikfar, 2020). Globalisation has significantly affected leadership through increased competition, increased opportunities, customer and market base. As such, leaders in the Middle East adopt leadership styles that are aimed at enhancing their organisational performance. However, globalisation has also diminished the absolute powers of authorities in the Middle East which significantly rests on inequality and hierarchical societies (Nikfar, 2020). Additionally, free trade and economy significantly influence the leadership theories used in the Middle East and Iraq in terms of trade policies on exports and imports. The need to establish a balance in a particular country’s economy within Iraq and the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) results in the adoption of leadership skills that can facilitate economic development. Subsequently, the number of years gained by a leader in trainings and exchange in experience greatly influences their decision-making skills. The presence of demanding situations within organisations compels managers and leaders to embrace varying leadership styles. Leadership in Iraq, the Middle East and the Arabic countries is largely considered to be democratic, welcoming and transparent (Nikfar, 2020). As such, the general approach to the leadership styles in the presence of other NGOs within the region would be aimed at bringing about initiatives for its people. Additionally, internal factors also have a significant influence on the leadership styles in MENA and Iraq. Culture and religion are significant aspects in Iraq and MENA. As such, the two internal factors have significant influence on the leadership styles in the Iraq and MENA considering that trust is the guiding principle in the Arab Middle Eastern culture. Additionally, the Arab Middle East places significant emphasis on power-distance whereby a leader deserves to be trusted while the members are expected to cooperate without questioning the existing leadership (Hofstede Insights, 2020). Leadership styles are thus influenced in consideration of the Arabic culture and religion which are the expected societal rules that are perceived as beneficial guiding principles. The factors delineated in the above literature regarding the factors influencing the Eastern leadership styles differ from the Western leadership practises on significant levels. While the Eastern leadership practices are more directive, the Western practices are flatter in the sense that they are more prescriptive (Wangmo, 2019). As such, the leadership practice gets based on informing the employees on the end goal expected by organisation and trust them in finding their way towards achieving their goal. Additionally, as part of the Western leadership practises, managers are accustomed to passing more challenges on the line inclusive of organisational employees which is different in the Eastern perspective that is built upon trust and respect for the authority in solving problems (Wangmo, 2019). The leadership styles applied in the Western context provide a broader platform to aid in innovation without restricting individuals regardless of their positions. The different leadership perspectives between the Western and Eastern ideas on leaderships thus can yield different levels of innovation in NGOs due to the different theories and styles of leadership, the factors affecting the use of leadership styles in the context of the NGOs, the innovation theories and the main drivers of innovation in NGOs.

Leadership theories, styles and background

Leadership is one of the most widely discussed and studied concepts in strategic management literature (Saunders, 2020). Different conceptualisations of leadership have emerged over time due to a lack of harmonisation in definition by different scholars thus limiting research opportunities (Day, 2014). The evaluation of the leadership theory in western world began with the “Great Man” approach in the 19th century, which was proved by Theodore Roosevelt, Abraham Lincoln, etc. This approach led to the development of the “Great Man Theory” by Thomas Carlyle (Uslu 2019). However, the commencement of twentieth century built better perspective for management thereby for effective leadership. There was more focus on leadership traits, such as model of Trait-Leadership Model which has further developed in recent years as “The Leader Trait Emergency Effectiveness Model” and “Model of Leader Traits, Behaviours, and Effectiveness” (Blunt and Jones 1997).Nevertheless, in 1940, researchers at Ohio State University Studies focussed on people focussed and task focussed behaviours whereas researchers at University of Michigan team focussed on production oriented and employee-oriented behaviours of a leader.Ohio state and Michigan studies on leadership are effective to develop suitable leadership and management strategy where the leaders try to lead the followers towards achieving success. Ohio State of university reveals that there are two characteristics of leaders and each is independent to another (Deshwal and Ashraf Ali, 2020). Two leaders’ behaviour are initiating structure and considerations. Under initiating structure, the leader toes to create good corporate structure for leading the employees and on the other hand, consideration refers to showing concern for the feelings and needs of the followers, where the leaders focus on fulfilling the requirements of the followers for motivating them in long run as shown in Figure 1 (Deshwal and Ashraf Ali, 2020).

On the other hand, Michigan studies of leadership refer to the high and low leadership control where the activities are close supervision, job centred, general, employee oriented and laissez-faire continuum (Harrison, 2017). If the leaders tend to close supervision and job centred approach, there is increased leader control and on the other hand, if there is laissez-faire concept in the organisation as well as employee empowerment, there would be increasing employee involvement for encouraging their creativity to perform better. In 1964, Jane Mouton and Robert Blake developed a grid model that integrated five distinct leadership styles which were primarily concerned with people and production. There were further developments of several other theories within the same decade with the initial introduction of contingency approach as the major focus. For instance, Schmidt and Tannenbaum developed the “Leadership Continuum Theory” in 1958 (Lumen, 2020; Asrar-ul-Haq and Anwar 2018). Also,Fred Fielder developed the “Fielder Model” in the mid-1960s. The “Situational Theory” was then developed by Hersey and Blanchard in 1969 (STU Online, 2014). Subsequently, the“Leader-Participation Model” was developed in 1973 by Philip Yetton and Victor Vroom. Further, the “Leader-Member Exchange Theory” was developed in 1975 (Lumen, 2020; Asrar-ul-Haq and Anwar 2018). Finally, the “Cognitive Resource Theory” developed by Joe Garcia and Fred Fielder in 1987. According to the study of Schmidt and Tannenbaum (1958) on leadership, a shift from autocratic leadership by leaders would heighten employee participation and further amplify the employees’ decision-making abilities. The domains of leadership can be classified as either manager-centred or subordinates-centred (Harrison, 2017). However, the subordinates-centred approach provides an opportunity to empower the followers which consequently increases their productivity. Subsequently, in terms of leadership development, Bass and Avolio designed the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ) intended to measure a wide range of types of leadership while identifying the attributes of transformational leadership (Avolio and Bass, 2004).As such, the different leadership theories focused on various distinct factors such as people, production, task, and behaviour which implies that external factors orleaders’ desired outcomes significantly influence the leadership styles that they choose to adopt. Authentic leadership is another significant style whose consideration can provide invaluable information on the spectrum of leadership. Authentic leadership is the design of leader behavior that focuses on and enhances desirable ethical climate and psychological capacities. It encompasses four components which include fostering self-awareness, a balanced processing of information, internalized moral perspective and relational transparency among leaders thus enhancing positive self-development among followers (Walumbwa et al., 2008). The approach of this leadership emphasizes on the ethical aspects of the leader-follower relationship while describing the behaviors that lead to a trusting relationship. Authentic leaders are honest and open when interacting with others and also have a general positive perception of life. As such, many practitioners have constantly encouraged organizations to embrace the notion of authentic leadership as it can lead to positive relationships and stronger commitment to an organization’s visions. In addition to the traits, skills and competencies underpinning effective leadership depicted in the previous, two additional areas worth further consideration can be found in the existing body of research. On the one hand, the importance of cross-cultural leadership competencies has been highlighted by Taleghaniet al. (2010), revealing that the effectiveness of a leadership style varies between different cultural contexts. As a result, effective leaders need to adjust their styles to suit the needs of the local employees and the cross-cultural competency is becoming increasingly important in the context of the globalised business environment (Taleghani et al., 2010). On the other hand, the recent outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic has emphasised the crucial role of effective leadership in shaping the organisations’ ability to survive during the times of a crises. As pointed out by Diraniet al. (2020), it is the authentic leadership that results in the most positive impact on the organisational performance during these challenges times. Hence, authenticity, congruency between values and behaviours and ability to from strong relationships with followers can be viewed as essential competencies in this era (Diraniet al., 2020).

Take a deeper dive into Leadership: Diverse Definitions and Insights with our additional resources.

The approaches of leadership in the West and East are different in terms of their value system, organisational dynamics and cultures. However, the Western theories have a negligible cultural influence compared to the significant Middle Eastern and Arabic culture that significantly influences their leadership theories. The western culture is a low-context culture while the Middle East and Iraq are high-context culture. As such, it is difficult to harmonise the differences in cultures in the two distinct environments (Abi-Raad, 2019). The Western theories of leadership are described as having advanced through the six periods of trait, behavioural and situational theories, transformational, charismatic, visionary and situational theories. Conversely, Iraq and the Middle East are structured upon an authoritarian form of leadership which results from their culture. The leadership styles adopted in Iraq have a significant impact on innovation in NGOs due to the unilateral involvement of managers and leaders in decision-making. Culture significantly influences leadership which subsequently results in difference in innovation in NGOs as based on the topic under discussion. It is difficult to harmonise the leadership styles from the Western culture and the Eastern culture due to the broad cultural differences. The framework developed by Geert Hofstede evaluates the cultural dimensions of a country and then further discerns the different ways that businesses get conducted across different cultures (Hofstede, 1980). The different national cultures are responsible for the global differences in organizational cultures, management styles and employee motivation. As such, understanding the country’s collective mental programming is salient for leaders to understand and incorporate the most effective leadership styles in organizations. Using the Hofstede site, a comparison of Iraq, UK, USA and Iran will further give a light about the differences in the Western and Eastern cultural attitudes as shown in Figure 3 below. Iraq and Iran belong to the Eastern culture while the USA and the UK are harmonised in the Western culture. In consideration of the dimensions of power distance, Iran has a score of 58 which is intermediate and justifies the presence of a hierarchical society. However, Iraq has a score of 95 which indicates its extreme nature of inherent inequalities and intense subordination under autocratic leadership. Iraq, being a country in the Middle East, thus operates under a culture with a significant emphasis on hierarchy. In contrast, the UK has the least ranking of the PDI (Power Distance Index) of 35 which defines the country as a strong believer on equality and that inequality should be mitigated (Hofstede Insights, 2020). The US also endorses for the equality among its population although it ranks higher than the UK. However, the two countries share similar cultural values in relation to equality as being for both the leaders and followers. Subsequently, in the dimension of individualism, Iraq and Iran have a lower ranking which indicates that they are a collective society. Iran has a ranking of 41 while Iraq operates more collectively at 30. Conversely, the US and the UK are culturally individualistic which indicate that they focus more on themselves and their immediate circle. In terms of rankings, the US tops the table at 91 followed by the UK at 89. The dimension of masculinity conveys a narrow margin of variation between the Western and Eastern culture. Iraq leads at 70, followed by the UK at 66, the US at 62 and finally Iran at 43 which identifies it as more feminine than masculine (Hofstede Insights, 2020). The aspect of masculinity can play a significant role in steering innovation in NGOs in Iraq considering that people are majorly driven by competition and the need for success. However, other cultural factors might impede the level of innovation such as uncertainty avoidance. Uncertainty avoidance is a cultural dimension that further reveals the cultural differences between the West and the East. Iraq and Iran, ranked at 85 and 59 respectively focus more to mitigate the uncertainties associated with the unknown which barricades innovation when combined with their preference for a collective society (Hofstede Insights, 2020). In contrast, the US at 46 and the UK at 35 embrace the day as it is without the need to counter the uncertainties associated with the unknown (Hofstede Insights, 2020). The combination of an individualistic society and a curious mind enhanced by uncertainties steers innovation compared to the different cultural perspectives of the Eastern cultures. Additionally, in terms of the cultural dimension of long-term orientation, there exist a shift in similarities based on countries in the Western and Eastern cultures. The UK scores the highest at 51 which indicates that the country is more pragmatic in that it identifies modern education as the key for the future (Hofstede Insights, 2020). The UK’s view on long-term orientation enhances the capability of more innovations which in the case of the topic under discussion would thus promote innovation. The US comes second at 26 indicating that it maintains some links with its pasts while meeting its current objectives. On the other hand, Iraq and Iran, at 14 and 25 respectively are more considerate of their pasts despite their connection with the future.Finally, in the dimension of indulgence as a defining cultural element, the US and the UK are more indulgent indicating that both countries value willingly express their impulses regarding having fun and are more optimistic (Hofstede Insights, 2020). In comparison to Iraq at 17 and Iran at 40, the two countries are more restraint and less indulgent.

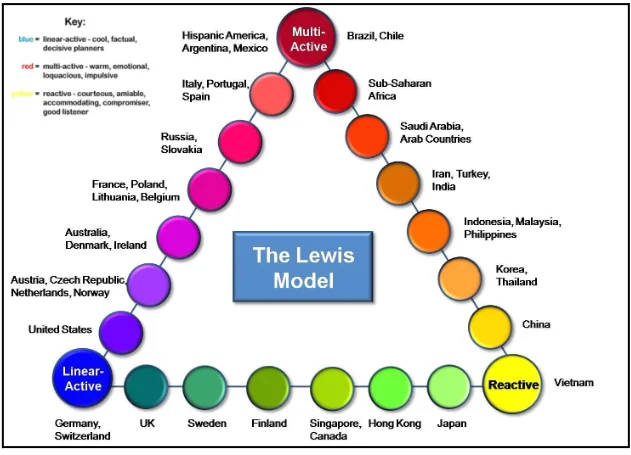

The Lewis Model provides a clear apprehension of the cross-cultural differences between the West and the Middle East and Iraq. The two regions are distinct based on the prevalence of cultures established in their activities. Lewis Model of cross-cultural communication is effective to analyse the cultural impacts on leadership. As per the diagram below in Figure 4, there are many international countries, and it is possible to analyse their leadership style and organisational practice to manage performance.

The population belonging to these cultures embrace different leadership styles and behaviours. For instance, the leadership practice in France is paternalistic and autocratic whereas management in Sweden is decentralized with democratic leadership. Likewise, the leaders in Germany try to achieve a perfect system through autocratic leadership with focus on consensus whereas in Netherland, the leaders are decisive and vigorous as they focus on achievement, competence and merit. Similarly, Russian leaders’ focuses on bureaucracy; Spanish leaders focus on charisma and autocracy; Chinese leaders adopt transformational leadership style; UAE leaders adopt autocratic and delegative style, whereas US leaders are charismatic, empowering, participative and directive at the same time (Sowmya et. al 2018; Cox et.al 2018; Suutari and Riusala 2001; and Perlitz and Seger 2004). Thus, different styles of leadership are practiced on the basis of cultural origins of the country and people. In depth of Lewis Model, Arab countries are between multi active and reactive. It is close towards multi active which indicates that the leaders are emotional, and they mostly talk about time to manage the working activities in the organisations. Additionally, the culture is towards people oriented and the leaders try to manage the subordinates by empowering them and improving involvement of the followers in the decision-making behaviour (Pavlović, 2019). Reactive culture also indicates people oriented, managing patient, using connections and there is link between social and professional life where the leaders show emotion and be polite to respect the followers and lead them towards achieving future success. On the other hand, the western culture is different from this, where UK and USA are close to linear active style of leadership. The Lewis Model indicates the significant differences between the Middle East and Iraq and the Western countries which are majorly linear-active. In this approach, the leaders are job oriented, confronts with logic, and base their arguments on facts and truth (Talalova, 2017).There is separate social and professional life among the leaders and subordinates and there is lack of people engagement in the organisational decision-making behaviour, where the leaders place a critical emphasis on job-related activities to achieve future success. Consequently, the next section will study the internal and external factors that affect leadership styles in Arabic culture generally and Iraq specifically.

Leadership in the Middle East

This first main part of the literature review is focused on the examination of leadership practices and effectiveness in the Middle East, pursuing a goal of presenting an overview of the available body of research on the topic relevant for this study. Afiouniet al. (2014) recognised that over the recent years, there has been a considerable increase in the amount of research exploring the leadership practices in the Middle East. Differentiating the Middle east from Western countries, Abi-Raad (2019) highlighted the practical challenges which limit the adaptation of western-style leadership approach in the studied context, supporting the need for a critical examination of the underlying cultural values that influence the development and implementation of specific leadership practices in the context of the Middle East. The significant influence of the Arab culture and Islam on leadership practices followed in the Middle East has been also recognised by Budhwar and Mellahi (2018). In general terms, Metcalf and Mimouni (2011) argued that there is a strong tendency in the Middle east to adopt directive styles of leadership, with authoritarian leadership style being highly prevalent in this cultural context. Common (2011) elaborated further on this notion and examined the specific patterns of leadership development in the Sultanate of Oman. The main findings reported by the author suggest that leadership practices in the Sultanate of Oman fall outside of the mainstream approaches to leadership as observed from Western countries and the mainstream academic literature. Common (2011) associated these differences with the strong influence of political leadership on organisational behaviour. A particular reference has been made by the author to the impact of the high-power distance dimension on the organisational behaviour in the context of the Middle East, revealing that this cultural dimension undermines intuitive decision making and gives rise to authoritarian approach to leadership. Further evaluation of the effects of cultural values on leadership and its subsequent practise in the Middle East has been presented by Sheikh et al. (2013) who specifically focused on the context of the United Arab Emirates. While the authors recognised a positive relationship between the use of a transformational leadership style and job involvement, the moderating effect of two particular cultural dimensions were also revealed. On the one hand, the level of collectivism significantly enhanced the positive contribution of a transformational leadership style on job involvement. Additionally, a negative impact of uncertainly avoidance on the aforementioned relationship was also reported. In general, the findings from this empirical examination revealed that cultural values held by individuals influenced the attitudinal responses towards transformational style of leadership. Since the population in the Middle East predominantly follows the teaching of Islam, the role of culture and religion has been studied extensively in terms of its impacts on the management and leadership approaches followed in Arabic countries.Ourfali (2015) provided a comparative evaluation of the leadership approaches between Saudi Arabia and the US, revealing that underlying differences in cultural dimension derived from Hofstede’s framework can be used to explain the deviation of leadership approaches in Arabic countries. Ali et al. (2010) also pointed out the higher level of collectivism in the culture ofArabic countries. According to the authors, it is the Islamic teaching and cultural traditions that reinforce the level of collectivism, consequently yielding more consultative and participative leadership tendencies in the Middle East.Further examination can be found in the work of Gates (2015) who applied Lewis model to investigate the cross-cultural differences in leadership, placing a particular focus on the context of the Middle East. The theoretical framework distinguishes three broad approaches towards leadership, namely linear active, multi-active and reactive. To begin with, Germany is often presented as an archetype of a linear active approach, with communication being very direct and task oriented. Secondly, multi-active approach is pursued in Latin America and can be characterised by a higher involvement of emotions and being more people oriented. Thirdly, reactive approach is based on active listening, diplomacy and being people-rather than task-oriented. Gates placed Saudi Arabia and other Middle Eastern countries in between multi-active and reactive approaches, revealing that people-oriented as opposed to task-oriented focus of the management seems to be prevalent. From a comparative perspective, Bealer and Bhanugopan (2014) investigated the use of leadership practices in the United Arab Emirates, Europe and the United States. In comparison to the two Western contexts, a lower prevalence of transformational leadership style was uncovered in the United Arab Emirates. Overall, the prevalent leadership styles and practices in the Middle East have been associated with the use of a top-down approach (Butler, 2009), charismatic leadership (Zaraket and Halawi, 2016) and consensus leadership style (Randeree and Chaudhry, 2012). Further insights can be found in the work of Yaseen (2010) who examined the specific gender-based differences in the leadership practices in the context of the Middle East. While men were found to rely heavily on the transactional and laissez-faire styles of leadership, women in the Middle East have been shown to increasingly follow a transformational leadership style (Yaseen, 2010). From a critical perspective, Mellahi and Budhwar (2010) identified the need for further research to enhance the understanding of the dynamics through which Islamic and Cultural values significantly influence leadership practices in the Middle East. Moreover, Metcalf and Mimouni revealed that overarching socio-cultural factors in the Middle East countries often distract the attention from the more subtle, yet highly influential, factors that determine the nature of leadership in individual countries. In other words, that cultural values vary between individual countries in the Middle East and hence, generalisation of these influences may undermine the validity of the conclusions drawn. A practical example can be made of the use of authoritarian and transformational leadership styles in the context of Middle East. While a generalised conclusion drawn in the existing body of literature points towards the prevalence of authoritarian styles of leadership, the presence of transformational leadership style has been highlighted. This critical perspective thereby emphasises the need for a targeted investigation of leadership styles in specific countries and industries.

Aldulaimi (2019) explained whereas Islam lays down features of leadership such as: the necessity for the worship practices to be collective and with the presence of the leader (imam) in prayer, Hajj, declaring the beginning and end of the time of fasting, as well as travel, Prophet Muhammad confirms that by saying, ‘if three Muslim travel together, they should choose one to be leader’ [Abo Daod: 2708]. Besides that, Islam refers to the necessity of obedience to the leader, such as obedience to God and obedience to the Prophet as Qur'an saying 'Obey Allah, and obey the Messenger, and those charged with authority among you' [4-59]. The leader (Imam) needs what is called (shura) is the style of decision-making such as consultation, Qur'an further says, “And their matters are attained by consultation between them” [42:88], but they differ as to whether the shura is just an opinion or that the imam is obliged to it. The features of leadership in Islam made it clear that a leader should be humble and set a good example, 'Ye have indeed in the Messenger of Allah excellent model' [Qur’an, 33-21].Aldulaimi (2019) has also revealed that the Arabic culture has traits such as men of tribes has heigh power and low individualism among them. Hence, leaders and managers in organisations are influenced by their family structure that they behave like fathers of the business. However, family and friendship duties take priories over others. Although, social networks are burdensome to leaders because they cannotignore these difficulty connections, which affect their decisions and behaviours when relatives interfere. Through the Islamic thoughts and Arabic culture traits we can find a contradiction between religion that describes leadership principles justice and culture that gives rights according to age, gender, tribe, or relatives. In summary, the topic of leadership in the Middle East has attracted a growing amount of research over the recent years. This body of research has predominantly focused on the examination of the cultural values which influence leadership practices in the studied context, revealing the common preferences for an authoritarian or charismatic leadership styles. The critical perspective within the existing body of literature however recognises the differences between individual countries and industry sectors. As a result, the claim depicted in the academic debate that transformational leadership style is largely in applicable in the context of the Middle East has been challenged, suggesting that the end for a more targeted investigation of the leadership practices in individual countries. The Islamic culture and the high-power distance dimensions are inherent in the Middle East which embraces the authoritarian style of leadership that downshifts the possibility of innovation from every organizational dimensions.

Leadership in Iraq

The topic the use of leadership styles in Iraq is relatively under-researched with only a handful of studies exploring the effectiveness of leadership in Iraqi organisations. Al-Tameemi and Alshawi (2014) referred to both the Ease of Doing Business index issued by the World Bank and the Corruption Perception Index issued by Transparency International for the characterization of the specific difficulties surrounding leadership and management in Iraqi organisations. Iraq has ranked at 165th place out of 185 countries listed in Ease of Doing Business Index (Al-Tameemi and Alshawi, 2014). Subsequently, the country occupies 169th place out of 176 countries in Corruption Perception Index. The limited ease of doing business in combination with high level of perceived corruption can be viewed as the main external factors undermining the performance of organisations in Iraq. Al-Tameemi and Alshawi (2014) however went even further and reported that poor leadership and ineffective human resource management practices can be viewed as the main internal factors contributing towards weak organisational performance in Iraq. Moving beyond the general appraisal of leadership effectiveness in Iraq as provided by Al-Tameemi and Alshawi (2014), the studies conducted by Habeeb et al. (2014) and Al-Husseini and Elbeltagi (2016) have focused specifically on the use of a transformational leadership style in the context of Iraq, assessing its effect on organisational performance. In the context of the higher education sector in Iraq, Al-Husseini and Elbeltagi (2016) supported the generally acknowledged positive effect of a transformational leadership style on organisational performance, revealing that it fosters both product and process innovation. Further insights were provided by Habeeb et al. (2014) who recognised the mediating effect of human resource management practices on the relationship between transformational leadership style and organisational performance. This study was based on a sample of organisations from the Iraqi banking sector and the authors pointed out the role employee participation, training and development programs and informal structure in mediating the aforementioned link. In their later work, Al-Husseini and Elbeltagi (2018) examined the effects of four specific dimensions of a transformational leadership style on knowledge sharing practices in the higher education sector in Iraq. Distinguishing between idealised influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation and individualised consideration as the core dimensions of a transformational leadership style, the authors revealed that it is the intellectual stimulation that exerts the strongest effect on the measured outcome variable. Similar results were obtained by Koran and Koran (2017) who examined the specific attributes associated with a transformational leadership style in terms of their impact on the motivation of teachers in the higher education sector in Iraq. Koran and Koran (2017) revealed that advancement opportunities, autonomy and responsibility represent the main elements shaping teachers’ motivation, supporting the contribution of the transformational leadership style towards organisational performance. While the education sector has been the subject of focus in numerous researches regarding the relationship between leadership and organisational performance in the context of Iraq, there are few exceptions that have assessed leadership effectiveness in other industry sectors of Iraq. An example can be made regarding the work of Khdair et al. (2011) which focused on the oil and gas industry in Iraq, investigating the link between leadership and workplace safety performance. The main conclusion drawn by the author however supports the general validity of the transformational leadership style as it was this style of leadership that has been found to improve workplace safety performance. In summary, the examination of leadership effectiveness in the context of Iraq is found to be very limited and predominantly focused on the education sector in the country. The findings within this body of research however reveal two main outcomes. As part of the first outcome, the usefulness and positive contribution of a transformational style of leadership towards organisational outcomes seems to be well-established in this body of research. On the other hand, the reviewed literature also recognises the apparent deficiencies when it comes to leadership effectiveness in Iraq organisations, suggesting that it represents a key internal factor undermining the organisational performance. The next sub-section focuses on the body of research that examined leadership effectiveness in the context of the NGOs sector.The gap ascribing to the limited research conducted on the efficacy of leadership in Iraqi organizations indicates that there should be a more targeted research related to this topic in Iraq. As such, the lack of sufficient research on leadership styles integrated in Iraqi organizations will provide a basis for this research upon which further research can be conducted in the future. The next sub-section focuses on the body of research that examined leadership effectiveness in the context of the NGOs sector.

Leadership in NGOs

This sub-section explores the leadership practices in the NGO sector, and recognises that the non-profit nature of organisations may influence the adoption of specific approaches to leadership as well as their outcomes in terms of organisational performance. Despite the possibility of similarity in the mode of leadership structure between profit-making and non-profit making organization, there exist a significant difference in their leadership structures due to their varying objectives. In line with the general conclusion depicted in the broader academic debate, the existing body of research on leadership practices in NGOs has predominantly focused on the examination of the effects associated with the use of a transformational style of leadership. Koo et al. (2017) reported that transformational leadership style enhances the level of employees’ trust and organisational commitment in the NGO sector, supporting the recommendation for the implantation of this particular style of leadership. Further research however reveals that the effect of a transformational leadership style on NGO performance is relatively complex. An example can be made of the findings reported by Hassan et al. (2017) who found that personality traits of the leader, namely extraversion, agreeableness and openness to experience, mediate the impact of a transformational leadership style on project success. Shiva and Suar (2011) went even further and recognised the moderating role of leader-member exchange, suggesting that while transformational leadership style enhances organisational commitment and effectiveness, this relationship is moderated by the extent of leader-member exchange. In their later work, Shive and Suar (2012) further reported that there is no direct impact of a transformational leadership style on the performance of NGOs. Instead, this effect is indirect and fully mediated by the culture that enhances effectiveness. Moving beyond the examination of the contribution of a transformational style on the performance of NGOs, Soodan and Pandey (2017) provided a comparative evaluation of the respective effects of participative and instrumental styles of leadership. While the participative leadership style has been associated with a positive impact on employees’ job satisfaction, the findings reported by Soodan and Pandey (2017) revealed that the use of an instrumental leadership style diminishes the level of job satisfaction. The positive contribution of a collaborative style of leadership has been also recognised by Mitchell (2015) who viewed it as one of the principal factors shaping the NGOs’ reputation for effectiveness. An additional layer of complexity into the studied effects of leadership styles on NGO performance has been introduced by Demir and Budur (2019). In line with the concept of the triple bottom line, the authors built on the premise that the performance of NGOs should not be solely evaluated in terms of economic impacts, but that environmental and social impacts should be also included in this evaluation for an increased evaluation spectrum. As a result, Demir and Budur (2019) provided a comprehensive evaluation of the effects of elected styles of leadership on the corporate social responsibility in NGOs. The use of a transformational style of leadership has not been shown to have any significant impact on the level of corporate social responsibility. Instead, it was the ethical leadership which predicted in NGOs’ performance in corporate social responsibility (Demir and Budur, 2019). From a critical perspective, Bromideh (2011) investigated the specific barriers which undermine the effectiveness of NGOs in Iran. The author reported that financial challenges, leadership and human resource management issues represent three main barriers for effectiveness of NGOs in this country. As a result, although the existing body of research are reviewed in the previous paragraphs posits the positive contribution of transformational style of leadership towards NGOs performance, the issues inhibiting the development and implementation of effective in the NGO sector also need to be considered.

To summarise, the examination of leadership practices in the NGOs sector has partially reaffirmed the applicability of a transformational style of leadership. Revealing that it influences the development of a supportive organisational climate that consequently leads to enhanced NGOs performance, organisational commitment and job satisfaction among employees. This body of research however also revealed the prospective uses of a participative leadership style and ethical leadership style, with the latter being the main predictor of corporate social responsibility performance in the NGOs sector.The leadership styles integrated in the NGOs significantly impact the level of employee involvement and their commitment with the organizational vision. The transformational and collaborative leadership styles are evidenced as salient in enhancing productivity in NGOs. However, internal factors such as personality traits, openness to experience and financial constrains convey the gap in determining the effect of transformational leadership in NGOs. The exploration of the concept of innovation will provide a solid understanding of how to align the effect of transformational leadership with performance in NGOs.

NGOs in Iraq

The emergence of NGOs in Iraq is associated with the fall of the regime instilled by Saddam Hussain under which any organisation operating in Iraq had to be connected to the state (Fox, 2019). The inherent risk associated with playing a role of an active member of the civil society in Iraq prior to 2003 has been well-acknowledged (ACTED, 2020). As a result, both institutional and socio-cultural factors have been put in place to minimise the involvement of citizens in the civil society. Limiting the potential for NGOs. The major change occurred in November 2003 when Paul Bremer III, US diplomat, introduced order number 45 which effectively formalised the role of NGOs in the civil society in Iraq (Fox, 2019). Additional changes have been introduced in 2011 with the new NGOs law which enhanced the level of independence and freedom enabling NGOs to operate in Iraq (ACTED, 2020). A distinction can be however made between the development of international and national NGOs in Iraq. The complex relationship between these two broad categories of NGOs has been examined by Genot (2010) who found that the initial interest of international NGOs followed the 2003 fall of Saddam Hussain’s regime. The principal goal of these international NGOs was to avert a humanitarian crisis in the war-torn country. The ongoing security concerns have however forced international NGOs to relocate into neighbouring countries or leave the region completely. As a result, when the humanitarian crisis in Iraq materialised in full in 2005, international NGOs have already left the country, failing to avert the humanitarian crisis. With the absence of international organisations, national NGOs have emerged since 2005 in Iraq to address the key issues within the civil society, focusing predominantly on averting the humanitarian crisis in the initial years. As pointed out by Genot (2010), the emergence of the national NGOs in Iraq has been observed rather than influence by the international NGOs. Consequently however, international NGOs have started to actively collaborate with national NGOs, relying on them to continue their humanitarian and developmental projects (Genot, 2010). While the emergency phase of the development of the NGOs sector in Iraq has been overcome, the conclusions drawn by Genot (2010) suggest that NGOs in Iraq are still seeking to define and establish their specific roles and missions. At the present moment. ACTED (2020) estimated that there are approximately 10,000 NGOs, including both registered and unregistered organisations. The list of NGOs published by NGOs Coordination Committee for Iraq (2020) however points to a relatively limited coordination within the sector, with only 68 national and 104 international NGOs being listed. The current attitudes towards NGOs in Iraq are found to vary considerably. On the one hand, Fox (2019) argued that NGOs have effectively become a key part of the social landscape in Iraq, fulfilling their role in civil society and providing humanitarian as well as developmental and educational services. On the other hand, a vary distinct perspective on the citizens’ perceptions of NGOs in Iraq has been presented by Cook (2018) who recognised that numerous individuals view NGOs as a reminder of the countries’ colonial history. In summary, the NGOs sector in Iraq can be still considered to be in its infancy stage, with individual organisations attempting to define their specific roles and missions within the civil society. Although the international NGOs often rely on national NGOs in Iraq to carry out their ling-term projects, the development on the NGOs sector in Iraq has not been driven by international NGOs.

Overview of NGOs in Iraq

NGOs can be categorised based on several distinct typologies. William (1991) distinguished between typology by orientation and typology by the level of co-operation. On the one hand, four particular categories of NGOs can be distinguished based on their orientation, namely charitable, service, participatory and empowering (William, 1991). On the other hand, typology by the level of co-operation includes categories of community-based, city wide, national and international NGOs (William, 1991). As discussed in the previous section, although the very development and current operations of the NGO sector in Iraq have been influenced and supported by international NGOs, their presence in the country is relatively limited. Appendix A presents an overview of the key NGOs operating in Iraq based on the report published by the NGO Coordination Committee for Iraq (2019). This list of NGOs operating in Iraq revels that international NGOs operating in the studied region often tend to rely on collaboration with local partners in order to promote the achievement of their underlying mission and values. As a result, in line with the conclusions drawn by Genot (2010), the relationship between international and national NGOs in Iraq can be characterised by two main functions. First, the international NGOs have established co-partnerships with national NGOs in order to achieve the common goals and objectives. While the international NGOs have gained more experience and have more resources available, the national NGOs are better suited to enact the strategic plans into practice due to their knowledge of the local society and communities (Genot, 2010). Secondly, international NGOs empower and support the national NGOs through the provision of training opportunities, guidance and funds. This aspect has been further strengthened by the historical withdrawal of international NGOs from Iraq due to the perceived security threats. A specific example can be made of the bomb attack in Baghdad which resulted in the death of UN leader, Sergio Vieira de Mello (UN News, 2003). The following sub-sections provide further discussion on the nature of NGO sector in Iraq, and it is the goal of the next sub-section to present a critical overview of the roles of NGOs in Iraq.

Roles of NGOs in Iraq

The examination of the role of NGOs in the contemporary society has attracted a considerable amount of attention from the research community. The fundamental notion in this body of research suggests that NGOs seek to address the failures of the national governments in order to support the development of the society (Banks and Hulme, 2012). As a result, NGOs can be viewed as a key force in fostering the level of development, promoting democracy and equality, and addressing key social issues, such as poverty (Lewis and Kanji, 2009). Over the years, the NGO sector has been subjected to increased specialisation, resulting in the development of several categories of NGOs, the roles of which include development of infrastructure, supporting innovation, facilitating communication, providing technical assistance, research and monitoring, and advocacy for and with the poor (GDRC, 2020). As pointed out in the NCCI Report (2011), it was the withdrawal of the state from the provision of services in key areas in Iraq that has enhanced the role of the NGO sector in the country. Hence, the overarching role of the NGO sector in Iraq can be found in meeting the socio-economic expectations of the population (NCCI Report, 2011). The critical perspective outlined by Abdo (2010) however suggests that the perspectives on the role of NGOs in Iraq vary considerably. While the proponents of NGOs recognise their contribution towards development and betterment of the society, the critics often view NGOs as a socially divisive force that effectively leads to the segmentation of the national movement and fragmentation of the social fabric (Abdo, 2010). Regardless of these opposing views on the role of NGOs in Iraq, both national and international NGOs that operate in this country seem to focus on the most pertinent issues affecting the society. Given the high level of inequality and poverty, the provision of humanitarian aid to the parts of population that are still suffering as a result of the aftermath of the military conflicts represents one of the key roles of this sector in Iraq. Additional roles of NGOs in Iraq can be however found in the promotion of democratic values, inequality within the society and sustainable development (NCCI Report, 2011). An interesting observation can be however drawn from the comparative evaluation of the focus of national and international NGOs operating in Iraq, as summarised in Appendix A. On the one hand, the focus of international NGOs is predominantly placed on alleviating poverty and empowering local communities that have been affected by the military conflict. Specific examples can be made of Action Contre la Fair, Concern Worldwide, Heartland Alliance, Seefar foundation, Un Ponte Per and numerous other international NGOs that focus specifically on the world’s most vulnerable communities. On the other hand, a more diversified focus can be observed from the missions of national NGOs operating in Iraq. While these organisations still place alleviation of poverty and empowerment of local communities at the top of priorities, additional goals include promotion of human rights and supporting the development of democratic principles in the country. A specific example can be made of South Youth Organisation that seeks to promote “a strong and effective Iraqi society that can develop the political and social process and enhance the human rights and democracy”. Additional difference between international and national NGOs operating in Iraq can be found in the influence of religious values. While there are numerous international NGOs that place Christian or Islamic values at the core of their missions (e.g., Catholic Relief Services, Christian Aid, Dan Church Aid, Hungarian Interchurch Aid, Islamic Relief), the impact of religious values on the missions and conduct of national NGOs in Iraq is less pronounced. The critical perspective within the existing body of literature highlights the controversy surrounding the concept of humanitarian aid (Lischer, 2007; Belloni, 2007). The simplistic worldview offered by humanitarianism has been used by Belloni (2007) to question the role of NGOs in the contemporary society. According to the author, NGOs have largely failed to solve the problems they attempt to address. Instead, Belloni (2007) viewed the contribution of NGOs in terms of sheltering the developed countries from the spillover effects of the political and humanitarian crises around the world. This critique was further elaborated by Lischer (2007) who distinguished three specific forms of interactions between NGOs and the military. The author classified the role of NGOs into three particular functions, namely humanitarian soldiers, aid workers as government agents and humanitarian placebo. The main obstacle preventing NGOs from addressing the needs in the society has been perceived by Lischer (2007) in the inadequate security which effectively prevents NGOs from fostering the stability and meeting the humanitarian needs of the local population. Additional insights can be found in the discussion provided by Lischer (2007) regarding the role of NGOs as government agents, suggesting that when NGOs operate in a close proximity to the military intervention forces, they may be perceived by the local population as government agents rather than humanitarian actors. This critique raised by Lischer (2007) and Belloni (2007) however predominantly relates to the actions of international NGOs.

NGOs and funding in Iraq

Funding represents a key challenger for NGOs, affecting their ability to follow the underlying values and address key objectives defined in their missions’ statements (AbouAssi and Trent, 2016). As pointed out by Batti (2014), funding mechanisms relying solely on the generosity of the donors is often insufficient to meet the needs of NGOs in full. From a theoretical point of view, three particular sources of funding for NGOs can be distinguished. To begin, the first source of funding revolves around the aforementioned generosity of donors. In addition to the considerable fluctuations in the level of this form of funding (Parks, 2008), the main critique of relying on the funding from donors has been highlighted by Batti (2014). The author revealed that the pressure to mobilise resources may in fact lead NGOs to compromise the underlying values they sought to protect and foster. A similar conclusion has been drawn by AbouAssi and Trent (2016), revealing that it is the source that it is the source of funding and donors’ perceptions which influence specific changes in the focus of NGOs, compromising their integrity and ability to deliver a positive impact on the targeted social and environmental issues. Further empirical support for this claim can be found in the work of Parks (2008) who pointed towards the process of re-aligning priorities pursued by NGOs in order to make them more competitive in terms of receiving funding from donors. In the specific context of the Iraqi NGO sector, the donor funding reached its peak in 2003 with a total funding from the international community reaching $3.4 billion (Relief Web Press Release, 2012). The level of funding derived from the private sector has however gradually declined and in year 2008, only 9% of this value was received by NGOs operating in Iraq (Relief Web press Release, 2012). The second main source of funding is derived from government grants and provisions. Ali and Gull (2019) provided a comprehensive review of available research on the impacts of government funding on NGOs. The main outcome drawn by Ali and Gull (2019) highlights the complexity surrounding the impacts of government funding on NGOs. While the authors recognised that this form of funding can be highly beneficial and improve the performance of the NGO sector, Ali and Gull (2019) also acknowledged the critical perspective within the existing body of research which points towards a range of undesirable outcomes. A specific example can be made of the growing evidence for mission draft caused by government funding. Similarly, to the changes in NGOs’ values and missions in order to attract funding from private donors as discussed in the previous paragraph, the use of government funding has been also found to lead to the mission drift of NGOs, compromising their integrity and performance. Ali and Gull (2019) went even further and suggests that under specific circumstances, the provision of government funding to NGOs may lead towards their loss of autonomy. The second key limitation of government funding for NGOs raised by Ali and Gull (2019) revolves around the crowding out effect. In practical terms, NGOs that receive funding from the government have more resources and are able to outperform other NGOs in the specific sector. In turn, this crowding out effect results in the under-performance of the NGO sector (Ali and Gull, 2019). Additional findings were reported by Bloodgood and Tremblay-Boire (2017) who recognised that government funding for NGOs may in fact discourage NGOs from engaging in monitoring of the public policy, thus compromising the values of promoting democratic and equal society. In Iraq, the NGOs Law no. 12 of 2010 Article 13 defines three available sources of finance for NGOs, namely “members’ fees and dues; internal or external donations, grants, bequests and gifts; revenues from their activities and projects” (Relief Web Press Release, 2012). These legal provisions make no reference to provision of government grants, forcing NGOs operating in Iraq to rely mainly on the donations from the private sector. A different situation is however in the Iraqi Kurdistan Region in which the Law of Non-Governmental Organisations of 2011 Article 13 Section 4 stipulates that “organisation may receive income from – the organisation’s share of any allocation in the region’s annual budget, and any other grants or assistance provided by the government in support of the organisations’ projects” (Relief Web Press Release, 2012). The third potential source of funding for NGOs arises from their activities and projects, as defined in the NGOs’ Law no. 12 of 2010 Article 13 (Relief Web Press Release, 2012). However, since NGOs operating in Iraq are predominantly focused on the provision of humanitarian aid, addressing poverty and promoting development and empowerment of local communities and broader society, their activities do not provide a reliable source of funding. Overall, the source of funding is found to have a significant impact on the options of NGOs and all the funding options available for NGOs have been associated with their respective risks and limitations. In the context of Iraq, the legislation and government policies inhibit the ability of NGOs to rely on the funding from government grants, resulting in their reliance on the funding received from donors within the private sector. In addition to the volatility of this source of funding, the critical perspective within the existing body of research points towards the prospective negative impacts of this funding strategy on the integrity and NGOs’ ability to achieve their developmental objectives. In practical terms, since NGOs need to compete for funding available from the private sector, they have a strong incentive to align their operations and goals with the interests of the prospective donors (Parks, 2008; Batti, 2014).

NGO authorisation

The authorisation to establish NGOs in Iraq has been enacted by Article 39 of the Iraqi Constitution which provides the freedom of establishment of any association, organisation or political party (NCC Iraq, 2020). The registration process for both national and international NGOs is relatively straightforward, relying on established administrative processes (NCC Iraq, 2020). In the specific context of the Iraqi Kurdistan region, these provisions are enacted in the Kurdistan non-governmental organisations law no. 1 of 2011, allowing NGOs to open branches both inside and outside of Kurdistan and Iraq (Jawad, 2015). Moreover, the need for an effective partnership between NGOs and the government is widely acknowledged in the existing body of literature, recognising its impact on the achievement of development goals (AbouAssi and Trent, 2016). While the traditional approach towards collaboration between NGOs and the government emphasises the need for partnership, a distinctive approach has been recently utilised in Slovenia. As summarised by Stremfeljet al. (2020), the country has opted for a professionalisation of the NGO sector in order to support the goals of sustainable development, effectively transforming NGOs into the public sector. The general level of partnership is however very limited in the context of Iraq, with the government playing a limited role in the promotion of the key socio-economic interests of the population and these goals being almost exclusively fulfilled by the NGO sector (Relief Web Press Release, 2012). In Iraq, leadership is significantly reviewed in the education sector. However, the full impact of leadership in Iraq is not entirely developed which thus extends the need for further research to provide a solid understanding on the effect of leadership in Iraqi organizations. Subsequently, leadership in NGOs is inherent in steering productivity and meeting their objectives. However, the non-profit nature of NGOs can influence the adoption of particular approaches to leadership and their outcomes in terms of organisational performance.Also, despite the relevance of transformational leadership in NGOs it iscomplex in terms of identifying its impact on organizational performance. The concept of innovation can however align the impact pf transformational leadership with organizational performance. Additionally, NGOs in Iraq are primarily established to promote the population’s socio-economic needs and it is supported by numerous proponents despite oppositions from several critics who term NGOs as socially divisive. The major limitation of NGOs in Iraq is security concerns which stall the effectiveness of the NGOs. Funding of the NGOs in Iraq is majorly from donors. However, other sources of funding include the activities of the NGOs and government grants which are practically inadequate for the progression of the activities of the NGOs. The establishment of NGOs in Iraq is also legal as identified in Article 39 of the Iraqi constitution (NCC Iraq, 2020).

Innovation in NGO sector

Innovation in the NGO sector has been described as important yet challenging (McDonald, 2007). With the research efforts in this context being relatively limited (Zimmermann, 1999). The purpose of this third part of the literature review is to establish a conceptual and empirical basis for the examination of innovation in the NGO sector. Hence, the critical discussion starts with an overview of the key innovation theories (Section 2.4.1) that provide the basis for the consequent evaluation of differences between innovation in private enterprises and NGOs (Section 2.4.2) and examination of innovation drivers in the NGO sector (Section 2.4.3).

Innovation theories

According to Śledzik (2013), Schumpeter described carrying outinnovation as being the only function that is essential in history. Additionally, as part of his themes, he viewed innovation and entrepreneurship as salient in promoting economic growth. This sub-section reviews two dominant innovation theories, namely diffusion of innovation theory (Rogers, 2003) and concerns-based adoption model (Hall, 1979) in order to provide a theoretical background for the evaluation of innovation patterns in the NGO sector in Iraq studied in this paper. To being with, the diffusion of innovation theory initially introduced by Rogers (1957) focuses on the examination and explanation of the process through which individuals and companies adopt novel ideas and innovative solutions. The speed of adoption is defined by Rogers (2003) as the key factor defining innovation adoption behaviours of individual companies. Based on this dimension, Rogers (2003) distinguished five specific categories of organisations, namely innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority and laggards. The first category of organisations identified by Rogers (2003), innovators, refers to companies that actively pursue research and development, viewing their innovative capabilities as the key source of a competitive advantage. As a result, these organisations benefit from the first mover advantage but also bear the costs associated with the development of innovative solutions. The second category of organisations based on the framework introduced by Rogers (2003), early adopters, can be defined by the use of active scanning for innovative solutions and their adoption. Although these organisations do not benefit from the first mover advantage, their limited involvement in the research and development process also reduces the cost of innovating. The third category of organisations, early majority, refers to organisations that adopt innovative solutions once they are widely available. These actions are driven by the competitive pressures that force organisations to innovative in order to sustain their market position and organisational performance. Similarly, late majority category is comprised of organisations that adopt innovative ideas and technologies as a result of market pressure, but their slow response prevents them from gaining any significant competitive advantage as a result of the innovation. The fifth and the final category in the original framework introduced by Rogers (1957) includes laggards, or organisations that lag behind their competitors in the speed of adopting innovative ideas. A well-cited example of a laggard can be found in Kodak and its delayed shift towards digital photography which has eventually undermined the dominant position held by Kodak in the past and threatened the very survival of the organisation. Over time, a sixth category of organisations has been recognised in the academic debate – non-adopters, referring to organisations that do not adopt new ideas even after a prolonged exposure to these ideas and innovative solutions. The underlying reasons for non-adoption of innovations can be found in the continued reliance on established business practices as well as internal constraints which may limit the opportunities of established organisations to adopt innovative solutions. The second key theory of innovation reviewed in this section has been introduced by Hall (1979) and views the adoption process as being influenced by organisations’ concerns. The author pointed out three particular factors which affect organisations’ adoption of innovations as stages of concerns, levels of use and innovation configuration. To begin with, the stages of concern element of the concerns-based adoption model introduced by Hall (1979) reflects both external threats and opportunities associated with the novel technology. A high stage of concern can be therefore associated with substantial opportunities as well as considerable threats that the innovation could pose on the given organisation. Relying on the aforementioned example of Kodak and its delayed shift towards digital photography, the emergence of digital photography has caused a considerable level of concern among the key players in the photography industry. This level of concern was however very limited in the context of Kodak, undermining its ability to quickly adopt this innovation technology. The second factor outlined by Hall (1979) refers to the levels of use and thereby capture the scope of the impact of the innovation technology. The third and the final component of the concern-based adoption model developed by Hall (1979), innovation configuration, reflects the wider organisational factors that predispose a company towards innovating and adopting innovations. In other words, the innovation configuration is dependent on the organisations’ readiness for change and the presence of dynamic capabilities that enable adoption and implementation of the innovation solution. Overall, both the diffusion of innovation theory (Rogers, 1957) and concern-based adoption model (Hall, 1979) provide valuable insights about the process of adoption of innovation, linking the innovation adoption with both antecedents and consequences of this process. The following sub-section focuses on the examination of the differences between innovation in private enterprises and NGOs.

Differences between innovation in private enterprises and NGOs

Although the role of innovation in driving economic growth seems to be well-acknowledged in the existing body of literature, the concept of innovation has been traditionally studied exclusively in the context of the private sector (Zimmermann, 1990). The principal difference between innovation in private enterprises and NGOs sector can be found in the role of the market pressure, suggesting that consumer empowerment in combination with intense rivalry among existing firms stimulate innovation in private sector organisations. This difference can be supported by both of the aforementioned innovation theories. On the one hand, the application of the diffusion of innovation theory (Rogers, 2003) recognises the organisation-related factors that drive innovation adoption behaviours. These factors have however been studied specifically in the private sector organisations, questioning their applicability in the NGO sector. On the other hand, Hall (1979) viewed stages of concern, levels of use and innovation configuration as the main antecedents of innovation adoption. Although this theory of innovation was once again tested predominantly in the context of the private sector organisations, an argument can be made that the stages of concern as well as the remaining two antecedents are less developed in NGOs due to the weaker market pressure that would force them to engage in innovation. Additional difference can be observed in the size of organisations, with NGOs being predominantly small and medium sized enterprises which in general are less innovative in comparison to large organisations (Jaskyte and Dressler, 2005). A different perspective was however introduced by McDonald (2007) who recognised that NGOs are facing an increased level of pressure to become more business-like. The following section draws on this conceptual discussion and explores the specific innovation drivers in the NGO sector.

Innovation drivers

In contrast to the more developed literature on innovation drivers in the private sector organisations, the focus of the research on innovation drivers in NGOs has been almost exclusively narrowed down to the role of internal factors. This body of literature has however provided several valuable insights regarding the key factors affecting the level of innovation in which an NGO is engaged. McDonald (2007) revealed that it is the organisational mission which influences innovation, as it enables NGOs to focus their attention on the achievement of particular goals and objectives. Further insights were presented by Choi (2012) who found that it is the combination of a learning orientation and marketing orientation that exerts a positive impact on the innovation in NGO. A more general conclusion was put forward by Choi and Choi (2014), viewing innovative culture as the key antecedent of innovation in NGOs. An empirical investigation carried out by Jaskyte (2013) explored the effects of organisation-related factors on innovation efforts from a quantitative standpoint, linking the size of the board of directors and organisation’s age with a higher level of innovation in NGOs. Building on the discussion presented within the previous paragraph, an argument can be made that it is the leadership effectiveness which influences innovation in NGOs as it clarifies the organisation’s mission (McDonald, 2007), supports learning (Choi, 2012) and encourages an innovation culture (Choi and Choi, 2014). The specific role of effective leadership has been also studied directly, an example of which can be found in the work of McMurray et al. (2013) who supported the aforementioned propositions. A particular reference in this body of literature was made to the role of a transformational leadership style in driving innovation efforts. Jaskyte (2011) revealed that transformational leadership fosters both technological and administrative innovation. Furthermore, Lutz et al. (2013) reported a positive effect of a transformational style of leadership on the organisational change readiness which consequently drives the level of innovation. A similar observation was made by Sethibe (2018), highlighting the role of a transformational leadership style in shaping the innovation climate and innovation itself. Focusing on the notion that it is the market pressure which exerts a strong influence on the innovation patterns in private sector organisations, Ranucci and Lee (2019) examined the effect of funding paradigms on the innovation behaviours among NGOs. This relationship suggests that donors can be viewed as key stakeholders in the NGO sector, providing these organisations with a stimulus to engage in innovation. Two main conclusions were drawn by Ranucci and Lee (2019). On the one hand, a decline of long-term innovation was observed among NGOs depends on donations from external private sources of funding. On the other hand, however, a positive trend in long-term innovation was observed by the authors in NGOs that have organically developed and grown their network of donors. The latter source of funding has been shown to emphasise the interests of the donors and enable NGOs to utilise the social capital and access to new information that underpin effective innovation. The accountability to stakeholders has been however viewed by Khallouk and Robert (2018) as a key factor inhibiting the level of innovation displayed by NGOs. Essentially, the authors revealed that by focusing on the specific needs of the target stakeholders, the potential for engaging in innovation is constrained by the limited resources which are instead devoted to meeting the stakeholders’ needs. Furthermore, Khallouk and Robert (2018) argued that sine the success of innovation efforts is not guaranteed, the involvement in innovation efforts may be perceived as stakeholders as deviation from the NGOs’ mission statement. Additional insights were presented by Dover and Lawrence (2011) who approached the examination of the innovation patterns of NGOs from a critical perspective. The Authors recognised that innovation in NGOs is a key, yet unresolved, challenge and explored the effects of power imbalance on NGOs’ innovation. Four innovation pathologies were identified by Dover and Lawrence (2011) in NGOs that have displayed high levels of power imbalance, namely nothing happens, nothing changes, nothing scales, or nothing adapts. All four of these innovation pathologies lead to disappointing results in terms of NGOs’ ability to innovative, reflecting the inherent lack of motivation and coordination arising from power imbalances within these organisations.