UK COVID Testing Strategy: Gaps and Goals

Chapter 1 - Introduction

The aim of the Test to Release scheme is to reduce the quarantine period for overseas arrivals in England. Visitors from countries that are not on the UK's red list can undertake a private test 5 days after arrival and can end quarantine if the result is negative. The option for this test is voluntary. People can otherwise opt for quarantine for 10 days instead. The testing kit will be sent to the visitors address or the visitors can attend a testing site (Department for Transport, 2020). The visitors can leave their house to post the test or travel directly to the testing site. In addition to the Test to Release, the visitors must also take the 2 compulsory travel tests, which can be books at the same time as the Test to Release (Department for Transport, 2020). The test results may be returned between day 6 - 8 of the quarantine period. WHO states that testing is a crucial measure to the pandemic response in terms of tracing and containing the virus. The relevant strategy will consist of a portfolio of test types addressing a range of settings and situations. While molecular tests are mainly laboratory based, rapid tests are faster and cheaper in detecting the virus at the point of care (WHO, 2020). The question of supply and demand gap concerning testing kits in the UK is to be dealt with the aspects of planning and sourcing, making and delivery, the use of new technology, and with the metric to measure the performance. Markets based on the supply and demand principle can either be a developing market where the supply and demand are low; a growth market where the supply is low, but the demand is high; a steady market where the supply and demand are high; and a mature market where the supply is higher than the demand (Hugos, 2018, p. 160). Last year, the UK reported its Covid testing capacity to be short with less than 10,000 people tested on a daily basis. The UK has used a centralised system using private firms, such as Delloitte to run testing through the local drive-in and walk-in test sites. However, as they do not have expertise, it has not been able to reach out to communities that are hard to reach. The result is the use of half the capacity which is 40,000 tests a day (The Guardian, 2020; The Guardian, 2020; The Guardian, 2020). The 24 November 2021 data recorded by the government still shows that the tested results are lagging behind the capacity with 400,000 PCR tests conducted out of the 711,744-testing capacity (GOV.UK, 2021). The government has planned to deliver 10 million tests on a daily basis (BMJ, 2020).

1.1. Research questions and objectives

The figures demonstrated that the COVID testing scenario represents a developing market. In that context, the subject of this research will be to explore the supply chain of Covid testing kits from that perspective. This research seeks to understand and interpret the different types of supply chain strategies and mitigation strategies related to Coivid-19 testing kits in the UK. In that regard, the primary research questions will be as follows:

What are the critical challenges and which challenges have dominant influence in the supply chain of home-based Covid-19 test kits used under the Test to Release scheme due to the pandemic?

The objectives of this research are as follows:

To investigate the major challenges in the COVID-19 supply chain concerning testing kits used under the Test to Release scheme due.

To recommend insights for policymakers to address the challenges.

The objective of the research question is, thus, to identify any issues presented across various stages, such as their postage, shipping, collection, return and analysis and propose potential solutions during the Covid-19 pandemic, particularly regarding the market for the home test kits for Covid -19. The research will, therefore, analyse the market, methods and factors that are used to select a particular strategy, and the implication of such strategies. This research will seek to clarify the principal terms and theories in relation to the research questions and objectives.

Chapter 2 - Literature Review

2.1. Introduction

This literature review will explore the management practices and principles of supply chains in regard to home test kits for COVID-19 pandemics in the UK. It will particularly deal with the challenges and appropriate and recommended solutions to address those challenges. In that regard, the main purpose of this literature review section is to identify and evaluate the existing literature and seek to answer the principal research questions. The UK has shown the capacity to buy appropriate amounts of testing kits to meet the daily demands of testing. It has spent £161m on 5.8 million covid-19 testing kits that can give the result in 90 minutes. It has procured 5000 “Nudgebox” machines that can process 15 nose swabs daily without the need for a laboratory. It has purchased 450,000 LamPORE swab tests that can detect covid-19 in 60 to 90 minutes. However, these tests are also warned to not have met the claims made by the manufacturers supported by studies that they do not have adequate performance (Mahase, 2020). Basu and Write (2010 state that customer focus and demand is the first block for supply chain management. They create demand, which will determine the capacity of operation. Customers expect to receive materials that meet their needs including specification, time, and cost. Meeting these needs minimises the cost of stockholding. There must be quality information and data to understand the needs (Basu & Wright, 2010).

2.1. Digital supply chain innovation and management

The goal of meeting customers’ expectation to receive materials considering the quality information and data may be found in the use of digital space. A digital supply chain demonstrates the operation of the fourth industrial revolution (Kochan, et al., 2020). The use of digital platforms to run the Test to Release scheme demonstrates the digital transformation of supply chain management. This is necessary because the supply chain could be exposed to the risks arising from environmental, organisational and network-related factors that may affect the structure of the supply chain. The digital use can provide a smart and secured system (Kochan, et al., 2020). The digital-based supply chain is an integrated system that manages a supply chain involving a digital delivery of information across the network of members and customers. It can manage demand and supply and other collaboration (Underwood & Shelbourn, 2020). In relevance, it is also necessary to note the issue of the digital divide in the UK during the pandemic. Watt (2020) associated the response to COVID 19 with the issue of digital exclusion that might impact certain sections of the population. Resources that include digital health-care technology may not be accessible to all. This may be true to those people without COVID-19 fear to enter hospital buildings or who do not have access to appropriate devices (Watts, 2020). Because, a 2019 report by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) found that there is a large number of “internet non-users” in 2018, over 5.3 million internet non-users comprising 10% of the adult population. Together with those who lack the skill to use the digital service or lack the motivation to connect, it represents a digital inequality (ONS, 2019). Watt (2020) states that digital exclusion makes it difficult to obtain information, which further affects the wellbeing and mental health. This is a lack of or digital infrastructure, as Underwood and Shelbourn (2020) state, which can produce a gap between the digital aspects of the supply chain and the non-digital aspects (Underwood & Shelbourn, 2020). Such a gap may produce a failure of technology implementation due to a lack of project management regarding supply chain digitalisation (Benzidia & Fabbri., 2016). Ageron, Bentahar and Gunasekaran (2020) state that the understanding of project organisational issues, such as digital exclusion, is crucial to the technology implementation. Thus, the digital supply chain performance should have real-time information along with appropriate measures and metrics. This could provide visibility in the supply chain and bring the flow of materials (Ageron, et al., 2020). The UK has been struggling with supply chain problems regarding Covid-19 testing system due to disruption of the supply of critical test kits from the drug company Roche (Griffin, 2020). As Kochan and colleagues (2020) mentioned earlier, a digital supply chain is a part of the fourth industrial revolution where the emphasis is on the manufacturers and their capabilities regarding collection and distribution of real-time functioning and information across the stakeholders. There is an administration through the innovative technologies of supply chain procedures (Nia, et al., 2020). Hahn (2018) investigated the implications of digital supply chain management in both established companies and start-ups (collectively 200 companies) found that the approaches adopted by them are different from each other. Hahn found that the supply chain innovation focuses not only on productivity but also scalability and flexibility. It relies mostly on analytics and avoids human-centric approach and smart people technology. Hahn found that the established companies have adopted supply chain innovation to merely sustain existing business architectures. Whereas the start-ups rely on an operating model based on data analytics and platform economy. The established companies rely on problem-driven approach, whereas start-ups rely on business-driven approach (Hahn, 2020). Whichever is the approach, the solution may be found in a data–driven approach relying on applications of data tools. The Covid-19 pandemic is a global, regional and national challenge.

The response to such a pandemic may need to meet with the fast changing impact of the pandemic, in terms of the symptoms and medical response including testing. Thereby, a data driven solution, as Mwitondi and Said (2021) stated, may enhance the decision making processes. The present generation is the era of data-driven processes and solutions. Every relevant actor may need to work in an integrated manner as working independently may impede research progress and outcome achievement. They argued that this integrated approach may reduce or remove the knowledge gaps and other challenges, particularly when there is variation of the impact of the pandemic (Mwitondi & Said, 2021). Covid-19 pandemic has disrupted the channel of communication in the pharmaceutical and health industry. Not only these sectors, but the pandemic has forced organisations to shift their mode and manner of communication transformation, including the business processes and use of technology (Carroll & Conboy, 2020). This shift applies to the use of technological apps and platforms to contact trace, mass testing and tracing applications (Hellewell, et al., 2020). Dwivedi and colleagues (2020) stated that the ability to communicate clearly and effectively and awareness of the infection and the ways to prevent it may help manage the pandemic (Dwivedi, et al., 2020). However, Pedersen and Ritter (2020) stated that the pandemic has exposed severe challenges including poor execution and management of information flow among the problems of supply chain interruption, uneven distribution of customer demand, and deficient strategic decision making (Pedersen & Ritter, 2020). Walker and Brammer (2012) conducted a survey regarding the link between sustainable procurement and e-procurement adoption sampling over 280 public procurement practitioners from over 20 countries. They found that e-procurement and communication with the suppliers may support the environmental, labour, health and safety aspects of sustainable procurement. Whereas, it may hinder buying from small local firms that have not adopted e-procurement and communication (Walker & Brammer, 2012). Further, as Luthra and colleagues (2018) stated, in order to effectively implement the information and communication technologies, there should be an effective government support systems and subsidies, awareness of the tools and techniques, and information systems network design (Luthra, et al., 2018). The Covid-19 pandemic has caused the outbreak of new project management challenges. A digital-based supply chain can prioritise the focus on collection and distribution of real-time functioning and information across the stakeholders. As Nia and colleagues (2020) and Hang (2020) stated, the digital innovation applied to supply chain management can bring about enhanced productivity, scalability and flexibility with a data driven approach to solving problems and drive business.

2.2. Risk and resource management

Risk management assesses the external environment and contingent plan to address the crisis (Meyer, 2021). A supply chain works the most efficient when services, information and products are not disrupted by risks in terms of material, financial or information (Buzacott, 1971). Therefore, risks and uncertainties are widely acknowledged while formulating a supply chain framework. These risks can be at the supply and demand, process, operational, and security level (Christopher, 2004; Tomlin, 2006). A market that has high risk factors and consequently high impact from the risks will need a plan concerning mitigating risk response and contingency response. Therefore, as Chopra and Sodhi (2004) suggest, the supply‐chain risk management strategy must include a wider understanding of supply‐chain risk to scope and cross-relate larger numbers of risks and a risk‐mitigation approach that enables the adaptation of the risk management to new circumstances. For example, even when one identifies the factors that cause disruptions and understands its implication, it might increase the risk of delays (Chopra & Sodhi, 2004). One of the strategies to manage supply chain risks is to have an effective resource and capacity management. The management will be effective when the required capacity is supplied at each stage to the end users on a daily basis (Basu & Wright, 2010). The management is crucial in an industry that relies upon suppliers or distributors of raw materials and finished products (Gadde, et al., 2010). Meyer (2021) states that a strategic consideration in supply chain management is securing continuous supply even when the conditions are adverse. Supply strategy should have alternative suppliers and transport. This diversification of supplier or sourcing mitigates the risks concerning supply disruption (Meyer, 2021). In that regard, it may be noted that transports or logistics play an important part in the supply chain. Christopher (2014) stated that logistics connect the processes of manufacturing and delivery products to customers and meeting needs of the customers. Logistic management can, thus, impact the customers’ value equation. It optimises the flow of materials and supplies to the customers (Christopher, 2014). However, such flow of material is demanded to be on an agreed real-time, which means that the order should be fulfilled as expected and agreed (Christopher, 2014, pp. 7-10). Customers demand responsiveness, which also means meeting their needs quicker or in a shorter time period. The demand for agreed and quicker timely fulfilment of customers’ value and need indicates that the suppliers should be able to absorb risks without disrupting business continuity (Christopher, 2014, pp. 7-10). This is particularly relevant with inventory resource and risk management, which will be dealt with later. As such, the demand seeks a lean supplier based selection to improve quality, innovation sharing, costs reduction and an integrated scheduling. This will require the supplier rather than the customer to manage inventory (Christopher, 2014, pp. 7-10). While logistics play a crucial role in timely implementation and enforcement of supply chain, it is often exposed to factors that can disrupt the chain. Sanchez‐Rodrigues and colleagues (2010) stated that the main factors that can deter the sustainability of transport operations are delays, variable demand, poor information, constraints on delivery and insufficient supply chain integration. These factors affect transport. The constraints on delivery could be dependability, avoidance of loss and damage, speedy door-to-door delivery, regular collection and delivery, or flexibility (Button & Pearman, 1981, pp. 51-52). Pathak and colleagues (2021) state that the Covid pandemic has put the existing infrastructure under tremendous stress in terms of medical supply chain. Medical supplies including testing kits are critical supplies that are short across all the countries. They further state that despite investing billions of dollars to upscale the manufacturing, there are obstacles, particularly credibility of suppliers, upfront payment, diverse product requirements, customs certifications and tracking transportation vehicles. (Pathak, et al., 2021). This is a material flow risk. Tang and Musa (2011) discuss the material flow risks in three stages: sourcing, making and delivering. The three stages are interconnected and impact the flows (Tang & Musa, 2011). At the sourcing stage, risks, including single sourcing, flexibility in sourcing, supplier selection, supply product quality, outsourcing, and supply capacity could be experienced (Tang & Musa, 2011). At the making stage, risks of product and process design, production capacity, and operational disruption could be experienced. They arise due to the inability to meet market and technological changes, natural disasters, operational contingencies, or political instability (Handfield, et al., 1999). At the delivering states, risks of demand, excess inventory, and seasonality could be seen, but could also be impacted by rapid technology devolvement, changes in customer demand and short product life (Tang & Musa, 2011).

The UK seems to be seeing an inventory issue where only half the capacity of testing has been used. This issue is relatable to inventory management. Partovi and Anandarajan (2002) state that inventory management covers keeping control and overseeing products also from the customers’ side rather than the suppliers’ end. As such, the focus should be on maintaining the storage, controlling the inventory, and fulfilling the order. For that, planning and control plays a key role to establish an appropriate supply to the demand. Such planning governs time, effort, and money among other resources in relation to supply sustainability and resilience (Partovi & Anandarajan, 2002). If otherwise, there may be obsolete, redundant or even surplus stock costing more money, time and effort invested in storing and controlling the products (Partovi & Anandarajan, 2002). This occurs usually in uncertain or unpredictable situations, which can be mitigated through inventory management (Michalski, 2009).

2.3. Bullwhip Effect

Meyer (2021) states that innovation to meet new challenging conditions is needed. This may include upgrading the products and services and this may involve building stronger network relationships. For instance, Korean companies were the first to introduce testing kits. Their integrated network enabled them to activate their network of partners to quickly develop an effective supply chain (Meyer, 2021). In a demand-driven supply chain intelligence, there are three main factors that drive this chain. They are the capability of customer knowledge management, sharing knowledge and cooperation. These factors are put into operation through production planning, sourcing and logistics. The operation of these factors are necessary to achieve the supply chain and its performance (Yang, et al., 2021). If not properly managed, it impacts the performance of the supply chain. This is the bullwhip effect. Its effect occurs when there is a progressive increase in demand variance when order information passes upstream. It reflects the inefficiencies regarding the increase in total costs, deterioration of profitability, increase in inventory holding costs, and increase in capital cost (Dominguez, et al., 2015). Lee and colleagues (1997) proposed the four principle causes for the bullwhip effect including processing demand and lead time which are not null; order lot sizing; rationing and scarcity of the finished goods; and the prices variation. Campuzano and Mula (2011) further elaborated on the causes. They stated that the first cause involves a rational decision making that is sub-optimum where the demand forecasts are adjusted that also influence the inventory replacement rule resulting in significant fluctuation. The second cause involves managing orders downstream into lots to gain economies of scale in lot changing activities. The periodic replenishment increases demand variability. Such lot sizing can also be caused by transport optimisation (Campuzano & Mula, 2011, pp. 27-28). The third cause involves an increase in orders by customers when scarcity or unserved orders occur in a traditional supply chain. This involves more demand in the production system and increased safety stocks that results in more unsatisfactory deliveries or distorting of demand signals. The fourth cause involves offering products at a lower price so as to stimulate demand. Such elasticity in demand temporarily increases the demand ratios where customers buy in anticipation or increase stock. This affects the supply chain as when prices drop, the demand also drops (Campuzano & Mula, 2011, pp. 27-28) In order to mitigate the risk, Dongfei and colleagues (2014) suggested the application of a centralised and decentralised model predictive control strategies to control inventory positions concerning a four-echelon supply chain. They characterised the concerned models as bearing supply balance equations on product and information flows along with an ordering policy that serves as the control schemes. They used an Extended Prediction Self-Adaptive Control in the decentralised control strategy for predicting changes in the inventory position levels (Dongfei, et al., 2014). They locally minimise a cost function to obtain a closed-form solution applied to an optimal ordering decision concerning each echelon. This function comprises errors between predicted inventory position levels and their respective set-points, and a weighting function penalising orders (Dongfei, et al., 2014). In the single model, they used a predictive controller to optimise globally. They found an optimal ordering policy for each echelon. Such a controller relies on a linear discrete-time state-space model for predicting system outputs. The predictions are approached by either of the two multi-step predictors relying on whether the states of the controller model are directly observed or not. The objective function is a quadratic form and the optimisation problem is solved through a standard quadratic programming method (Dongfei, et al., 2014). Abedrabboh and colleagues (2021) have developed a combination of centralised and decentralised models to be applied to the supply chain management of PPE kits. Their proposed centralised-decentralised approach to the PPE kits supply chain comprises reporting by the healthcare facilities their demand to a central entity, which is assumed to have the power to fulfil the orders and set the PPE costs. The facilities optimise their orders by making individual stockpiling decisions (Abedrabboh, et al., 2021). Thus, the costs and supply is controlled centrally where the decision of stockpiling is decentralised. In regard to the UK, the NHS will be the central entity which has the commitment power to fulfil the orders. The NHS trusts will make individual decisions and all of them will pay the same price per PPE item (Abedrabboh, et al., 2021). They found two major factors that would ensure an adequate supply chain. They found that the storage capacity impacts the stockpiling ability that results in flattening the demand curve. They also found that earlier stockpiling would save costs and also ensured adequate supply of PPE (Abedrabboh, et al., 2021).

Bullwhip effect is caused due to inadequate management of the capability of customer knowledge management, sharing knowledge and cooperation. The centralised-decentralised model suggested by Dongfei and colleagues (2014) may ensure a centralised, coordinated network of entities and suppliers that reduce misinformation and enhance an effective forecast.

2.4. Project management capital

Alicke, Azcue, and Barriball of McKinsey & Company, a global management consulting firm that also caters to the healthcare systems and services sector, state that businesses are mobilising rapidly and setting up crisis-management mechanisms (Alicke, et al., 2020). Their short term responses, among other things, include managing cash and net working capital by running stress tests to identify and understand issues in supply-chain that may cause a financial impact. They stressed that such impact is caused by constrained supply chains, slower sales, or reduced margins. While project supply chain outcomes, it needs employment of internal forecasting capabilities needed for a weekly or monthly stress test concerning the capital requirements (Alicke, et al., 2020). A working capital is required to sustain the supply chain. Working capital will include the cash to purchase inventory and the cash received from sale. It is crucial to carrying out the daily operations of an organisation (Akkucuk, 2019). He, therefore, states that the accounts receivable days must be reduced to reduce the working capital thereby expediting cash collection. There is a direct link between the working capital and the supply chain activities. Working capital management will include managing and controlling the working capital accounts in order to make short term investments (Akkucuk, 2019). Peng and Zhou (2019) analysed the manner of optimising working capital in a supply chain perspective. They found that extending the payment terms may put financial pressure on the supply chain members. There should be a supply chain-oriented solution for managing working capital. For instance, preferable payment periods may be provided to companies giving high discount rates whereas companies that give low discount rates may be provided preferable prices (Peng & Zhou, 2019). This suggestion aligns with what Hofman (2011) also found. He analysed the approach of working capital management that is supply chain oriented by studying the impact of payment terms for working capital improvements. He cited the potential risk of exploitation by individual industries and powerful companies by enhancing their cash-to-cash cycles putting pressure on the suppliers and customers. He took a network perspective to the supply chain and stated that such exploitation of actors in the supply chain by a single powerful company could lower the supply chain’s overall financial wealth. Hence, he recommended a collaborative approach of working capital management. His recommendation is similar to that of Peng and Zhou (2019) that of extending cash-to-cash cycles of those companies that have lowest weighted average cost of capital, and shortening it for companies that have higher financing costs cycle. Hoffmann and Kotzab (20111) argued that this can mitigate the risk of unequal power distribution that could hinder a collaborative solution. The collaborative approach is also suggested by Akkucuk (2019), who stated that the optimisation of working capital, including that the management of the supply chain and the working capital requirement must fulfil the demands of the initial supplier to the final customer in order to reduce the total cash conversion cycle. (Akkucuk, 2019). The reason why a network perspective or a collaborative approach is needed is because a lack of financial cooperation will damage the operational efficiency of supply chains. This was observed by Vázquez, Sartal and Lozano-Lozano analysed the financial perspective of supply chain collaboration in the automotive industry. They analysed the 2001-2009 official data from 116 first- and second-tier suppliers in the Spanish automotive components sector. They found that the economic and technological elements are enhancing financial stress that compels companies to shift their credit needs and inventory requirements to the weakest suppliers. This generated a significant difference between the working capital of the first tier and second tier companies. Vázquez, Sartal and Lozano-Lozano suggested that such an approach improve the results of the former. However, this is likely to cause loss of production efficiency related to the supply chain. They further suggested avoiding such short-sighted attitudes in a cooperative oriented supply chain if they aim to reach upstream stages (Vázquez, et al., 2016). In collaborative supply chain management, both the financial and operational processes are jointly considered. Working capital indicates the overall supply chain performance. In regard to the supply chain recoveries during the Covid pandemic, among other end-to-end supply chain action, to reiterate Alicke and colleagues (2020), one of the tasks is to manage cash and net working capital through stress tests. As Akkucuk (2019); Peng and Zhou (2019); and Hofman (2011) pointed out, working capital management practices impact the economic and financial profitability of a company. LucíaRey-Ares and colleagues (2021) sampled 377 Spanish fish canned companies with data during the period 2010–2018. They found that the profitability of the companies is linked with collection period and inventory conversion period. They found evidences that demonstrate that granting the customers more collection days is likely to increase sales as this approach attracts new customers. Such an approach allows the customers to obtain funding at a lower cost than those provided by financial institutions. It also offers pre-payment benefit in terms of testing and enjoying the products (LucíaRey-Ares, et al., 2021).

This literature review has found that supply chain management can deliver a competitive and profitable advantage to organisations if the risks are addressed. It can also deliver effective operational performance and based on the literature discussed, particularly, (Underwood & Shelbourn, 2020; Ageron, et al., 2020), when it adopts a collaborative approach comprising a joint or shared management of an effective supply chain. This is found in the integrated digital-based supply chain, which can mitigate the risks of digital exclusion by focusing on real-time information to have an expanded reach of digital supply chain benefits. The collaborative efforts may also bring an effective flow of information and materials (Ageron, et al., 2020). This may enable communication between all the stakeholders. A centralised systems of access, tools and techniques and information network may enhance the integrated approach. The literatures of (Christopher, 2004; Tomlin, 2006) suggest that when there is a centralised system or network, comprising all users, suppliers, manufactures and policy makers, it could bring about an effective supply chain framework, which can address the risks associated with supply and demand, process, operational, and security level. The literature review in this research suggests that when the supply chain system is centralised and comprises a leaned (selected) set of suppliers and logistics partners, it could ensure a continuous supply chain. Based on the work of (Sanchez‐Rodrigues, et al., 2010; Button and Pearman, 1981: 51-52), when this system adopts a data-driven centralised approach, it may locate all relevant information and positions of the supply chain. where the controllers of the centralised system and suppliers and such stakeholders can take decisions meeting individual needs. This may encourage an interdependent logistics, speedy delivery, and costs reduction The primary demand for a centralised system of network with a decentralised approach of supply selection and delivery is aligned with what the model proposed by Abedrabboh and colleagues (2021). This model may address inventory, resource and capacity management issues to meet the demand curve. This may in turn manage working capital where cash-to-cash cycles could be extended for companies with lowest weighted average cost of capital and shortened for those with higher financing costs cycle (Akkucuk, 2019; Zhou, 2019).

Chapter 3 - Research Approach

3.1. Introduction

This chapter discusses the methodology employed to explore the aim and objectives of the research. It will discuss the method of data collection and questionnaire. This chapter will discuss the techniques used to formulate the research methodology.

3.2. Research Overview

Rajasekar, Philominathan, and Chinnathambi (2013) emphasise the importance of not only providing a presentation of methods for the research undertaken, but also verifying the reasons for adopting one or more techniques, tools, and processes, or in other words, research methods. Research is a method-oriented inquiry into a specified area of research (Kothari, 2004; Collis & Hussey, 2009). It is systematic in nature, which means that there is the involvement of a process determined by the researcher based on the objectives of the researcher and the research questions or thesis formulated by the researcher. It is methodological, which means that the researcher formulates a structure as per which they specify a research methodology for the research. Furthermore, based on the purpose and objective for the research study, the structure and design of the research is formulated (Saunders, et al., 2012). In a research study, the researcher may have access to a copious amount of data in journals, books, and databases all of which may not be relevant to the research study. The use of the research methodology helps the researcher to formulate a method by which the research is focussed. A research methodology refines the research; identifies the appropriate data needed to answer the research questions; and gives context to the data. Saunders and colleagues (2012, 2019) have developed the “research onion” to formulate the research methodology and design of the research.

This research has applied the above ‘research onion’ to provide guidance for the setting of the research method and design. Applying this research onion, the researcher defines the research philosophy, approach to theory development, methods, strategy, time horizon and techniques. Figure 2 below provides a top-down view of the four phases of the Research Process. The four-phase segregation: Research Process; Research Philosophy; Methodologies and Data Collection, collectively helps to provide a better understanding of the research design.

3.2.1. Research Philosophy

As per the research onion designed by Saunders, et al. (2012; 2019), the first task of the researcher is to identify and explain the research philosophy, which is explained as the system of beliefs and assumptions about the development of knowledge (Saunders et al., 2019). Identifying the research philosophy is the first step for the researcher because the researcher structures the research design according to their philosophical underpinnings which include positivist, interpretivism, pragmatic or realist philosophies (Creswell, 2013). It is also pertinent that the researcher makes choices related to research philosophy whether consciously aware or not and based on these choices a number of assumptions may be made by the researcher (Burrell & Morgan, 2016). These assumptions made by the researcher also shape the formulation of research questions, and the methods for collection and interpretation of the data (Crotty, 1998). The research philosophies that are generally applied by social science researchers include Positivism, Realism, Interpretivism, Objectivism, Constructivism, Post Modernism and Pragmatism. These research philosophies are different to each other and depending on the philosophy chosen, the researcher will take decisions regarding their methods and approaches. Realism is concerned with scientific practice and generally leads to empirical and critical approaches adopted by the researcher (Bryman & Bell, 2015). Interpretivism is critical of the scientific realist method and instead encourages epistemological consideration of views of the researcher (Saunders, et al., 2012). Positivism is driven by objectivism and applies scientific methods of enquiry (Easterby-Smith, et al., 2002). Postmodernism philosophy applies concepts like post-colonialism and capitalism as theoretical constructs that guide approaches to research and question the dispassionate social scientist trying to uncover a pre-existing social reality (Dickens & Fontana, 2015). Constructivism is premised on the idea that social actors are responsible for creating the phenomena. Pragmatism is based on the practical consequences of the research (Creswell, 2013). The philosophy used for this research is Interpretivism. Interpretivism is considered to have strong interconnections with qualitative research (Collis & Hussey, 2009). Interpretivism drives focus on the epistemological consideration of the views of the researcher (Saunders, et al., 2012). Interpretivism emphasises exploring and finding the correct meaning of the data in a contextual sense (Myers, 2013). Interpretivism helps the researcher in identifying and interpreting how people participate in social and cultural life, and how people attempt to make sense of the world around us. The research is about the Covid-19 Pandemic and understanding the fundamental meanings attached to this. Interpretivism has been selected for this research because it helps to identify and interpret the views and the opinions of the end customer concerning the issues faced and the potential improvements that may optimise the supply of home Covid-19 testing kits used under the UK Test to Release scheme. Interpretivism allows the researcher to get the researcher involved in the everyday activities of the participants in order to recognise and elucidate what is going on, instead of changing things (Kelemen & Rumens, 2008).

3.2.2. Research approaches to theory development

The second task of the researcher (according to the research onion) is to define their approach to theory development. There are three approaches to theory development, one of which can be adopted by the researcher. Deductive and inductive approaches are the two principal approaches (Collis & Hussey, 2009) whereas a newer approach in the form of abductive approach is also now applied by some researchers (Opoku, et al., 2016). The deductive approach commences from the point of identifying a general theory and then applying it to a research specific case or context so that the researcher applying a deductive theory is moving from general to specific (Perrin, 2015). The researcher applying a deductive theory first identifies the theory, then develops a hypothesis before moving on to collecting observations and then confirming the theory that they started within the first place (Perrin, 2015, p. 81). The inductive researcher takes the opposite approach to the deductive researcher in that they start with first observing some phenomena before collecting data on that phenomenon which finally leads to theory building thus moving from the specific to general (Collis & Hussey, 2009). The abductive approach also goes from observation to theory but uses a cyclical process so that the researcher establishes a dialogue between theory, data and social context at every stage of the research process (Opoku, et al., 2016). Thus, the abductive researcher moves between inductive and deductive approaches from time to time in the research process. For this research, the researcher has involved an inductive approach. Saunders et al. (2019) have noted that known premises can be used to generate untested conclusions and data collection can be used to explore the phenomenon. Therefore, applying Induction as an approach will allow the researcher to better understand the nature of the challenges that the Covid -19 tests supply chain is facing and help in formulating a theory in suggesting reconditions to improve the situation.

3.2.3. Research Methodology

The third step for the researcher is to identify and explain the method chosen for the research design. Creswell has defined research designs as “types of inquiry within qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches that provide specific direction for procedures in a research design” (Creswell, 2013, p. 12). Thus, there are three methods that the researcher can choose from, these being quantitative, qualitative or mixed methods.

Quantitative research analyses relationships between variables measured numerically and analysed through statistics. This strategy is associated with experimental and survey strategies. The quantitative research design can be a mono-quantitative study, which uses one data collection technique or a multi-quantitative study, which uses multiple data collection techniques. The qualitative approach is generally associated with Interpretivism but may also be combined with other philosophies including Positivism (Collis & Hussey, 2009, p. 46). The qualitative design allows the researcher to be close to the participants within a flexible framework (Collis & Hussey, 2009, p. 47). Qualitative research is ideal for research studies that ask for a more interpretative stance or involve multiple narratives and requires a deeper insight (Creswell, 2013). Whereas quantitative research uses numerical data, qualitative research uses non-numerical data (Creswell, 2013, p. 44). As mentioned above, this research uses Interpretivism and the qualitative research design as this is compatible with Interpretative philosophy, this is suited to the research study because the phenomenon under study will have subjective and socially constructed reasonings. The Mixed methods research design allows the use of multiple methods combining both qualitative and quantitative techniques for collecting data and analytical procedures. The mixed methods research approach is appropriate for studies that require a combination of qualitative and quantitative approaches (Creswell, 1994).

3.2.4. Research Strategy

Strategy is explained as the plan of how the researcher seeks to answer the research questions. Saunders et al. (2019) provide many choices, which are discussed here, and the chosen strategy is then explained in the context of this research study. Thus, the researcher can choose between experiment, survey, case study, ethnography, action research, grounded theory and narrative inquiry. Experiments are useful where the researcher seeks to study the probability of a change in an independent variable causing a change in another dependent variable by first devising hypotheses that can be tested in the experiment. A survey instrument is a strategy that allows the researcher to gather data that will answer questions on who, what, where, and how. The Case Study method contains an investigation of a contemporary phenomenon in a real-life context with more than one source of evidence (Robson, 2002). Ethnography studies the culture or social world of a group and is especially used in anthropology to study cultures of the “primitive” societies. Action Research is designed to create solutions to organisational problems and will have ramifications for the participants and organisation above the research project. Grounded Theory refers to the data collection techniques and analytic procedures and is used to develop theoretical explanations for social interactions. Finally, Narrative Inquiry collects and analyses complete stories as opposed to data from specific questions, as a result, the researcher will be getting a “meaningful whole”. In this research study, the researcher will use the Survey strategy because the focus of the researcher is to gather data related to the questions of who, what, where, and how (Saunders et al., 2019) of the Covid 19 test supply chain. In order to answer these questions, the researcher is required to get information from the private laboratories and the end customer on the supply chain and the difficulties they encounter. The format is a questionnaire survey, which is designed as an instrument with a set of close-ended and open-ended questions, with the aim to collect data from the respondents. This strategy will allow the researcher to gather information on the difficulties encountered in getting the test, the efficiency of the Test to release scheme and the end-user opinion on the scheme.

3.2.5. Research Time horizon

The fifth task for the researcher is to select the time horizon and whether the researcher will choose a cross-sectional or longitudinal study. Cross-sectional studies allow the researcher to study a particular phenomenon at a particular time, or take a snapshot so to speak. Longitudinal studies have the function to study change and development, a measure of control over some of the variables studied. The time horizon depends on whether the research is a ‘snapshot’ to a particular time or a series of ‘snapshots ‘more like a diary for a given period (Saunders et al., 2019). For this research the selected time horizon is cross-sectional. This selection will allow the researcher to study a particular phenomenon in time, so as to provide a snapshot of the UK Test to release scheme in the global pandemic with Covid 19, for which data is being collected through a questionnaire survey.

3.2.6. Research Techniques and procedures

The last layer on the research onion is the techniques and procedures, which refers to the data collection and the analysis procedures. Data will be collected through a questionnaire survey, and it will be addressed to the end customer who has used the ‘Test to release scheme.’ Data will be analysed, measured numerically and analysed through statistics.

3.3. Data

This chapter will review how data collection was realised and what different types of data have been used.

3.3.1. Source of data

This thesis will encompass two different types of data collection, secondary data( literature review) and primary data( online BOS (JISC) questionnaire). Secondary data collection uses the same research principles and research methods as the primary data collection. The key to secondary data collection is applying theoretical knowledge and utilising existing data to address the research questions. Accordingly, a literature review was conducted including review of books, journals, articles, and academic research papers to help address the research questions and to identify possible recommendations to optimise the pharmaceutical supply chain for the PCR tests used under the Test to Release UK scheme. Primary data will be collected through an online BOS(JISC) questionnaire survey, collecting data from the end-user on PCR tests delivery, shipping, and issues encountered. The primary data collection helps to identify the areas in the pharmaceutical supply chain that need optimising. Data will be collected from travellers who need to quarantine on arrival in England. These include persons who are either unvaccinated or have been in a country or territory on the amber list in the 10 days before arriving in the UK.

3.3.2. Design of the survey questionnaire

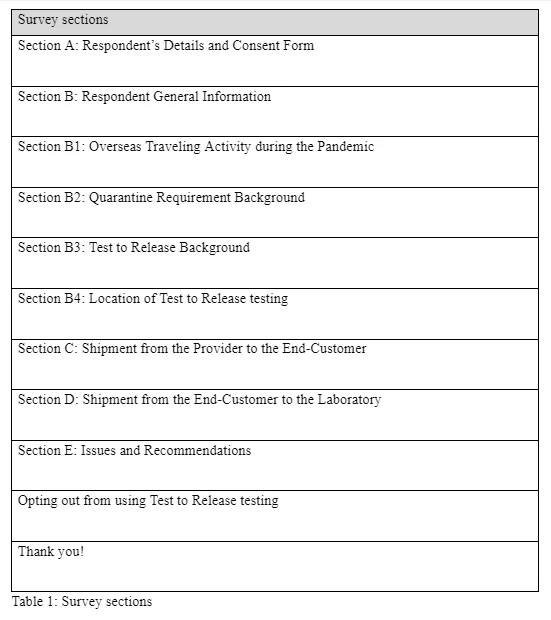

An online survey will collect information about posting, shipping, and return of the test to the laboratory to be analysed and potential issues that the end-user may encounter, to propose solutions to optimise the pharmaceutical supply chain further. The questionnaire has close-ended questions and the participant will be selecting from the given options. The questions will allow the participant to select 1 or multiple answers. The questionnaire is divided into 11 sections as per the below table:

Some of the questions from the questionnaire are designed to be mandatory and eliminatory, to ensure data integrity. The below image presents the current sequence, routing and relationships between your survey pages:

The word questionnaire can be found in the appendix.

3.3.3. Survey Tool BOS(JISC)

The tool used to create and distribute and analyse the survey is JISC Online Survey (formerly Bristol Online Survey - BOS). It is entirely web-based with no limits on the number of surveys you can create or the number of respondents you can have. (University of Oxford, 2021). The licencing for using the toll was provided by Coventry University, and all the data will be stored on the university’s servers in accordance with data protection.

3.3.4. Survey distribution and analysis

This thesis will collect data from travellers who need to quarantine on arrival in England. These include persons who are either unvaccinated or have been in a country or territory on the amber list in the 10 days before arriving in the UK. Also, participants must have opted to pay for a private Covid-19 Test to Release test on Day 5 upon their arrival in England to end their compulsory quarantine earlier considering the receipt of a negative test result. The data collected will be analysed to showcase the issues affecting the smooth distribution and collection of Test to Release Covid-19 tests and help the Researcher to identify how their supply chain can be further improved. An online invitation containing the link to access the survey and the Participants Information Sheet (PIS) will be sent to targeted groups. The participants are made aware that participation in the survey is not mandatory and they have the right to withdraw by contacting the researcher by the date they can find in the PSI. Anonymity is an important aspect, and all data will be anonymised before conducting the analysis and it will be presented in an anonymised way r data will be processed in accordance with the General Data Protection Regulation 2016 (GDPR) and the Data Protection Act 2018. All information collected about you will be kept strictly confidential, data will be referred to by a unique participant number rather than by name. All the data will be stored in Coventry university’s servers and the researcher has the responsibility to delete the data 1 year after the research is completed, in concordance with GDPR. The data collected will be analysed to showcase the issues affecting the smooth distribution and collection of Test to Release Covid-19 tests and help the Researcher to identify how their supply chain can be further improved. Analysis of data will be done analytical and data will be presented as pay charts and bar charts.

3.4. Ethics

This research will not directly impact the participant’s health or safety, however, confidentiality, anonymity and data protection are essential to cover during the data collection process via survey, questionnaire. For this research, a request for an ethics peer review has been made in accordance with the Coventry University Ethics process. The researcher had the obligation to fill an application with a basic overview of the project and an ethics panel to analyse and approve the project before conducting any data collection. Prior to filling the questionnaire, the participants’ have been informed that their participation is voluntary, and they reviewed and signed the Participant Information Sheet and the Informed Consent Form, both forms can be found in the Appendix. The project has been approved by: Supervisor: Dr Maria Triantafyllou, Module Leader: Dr Owen Richards and final Anonymous approval from the Ethics panel

3.5. Conclusion

This chapter detailed the Research Process data coaction and the Ethics process used for this project.

Details can be found in the table below:

Chapter 4 – Data Analysis and Discussion

4.1. Data analysis

The aim of this research is to gather a range of perspectives on the components and challenges of supply chain management. It started with the assumption based on data represented in this research that the UK is facing challenges in terms of short in testing capacity and lack of expertise in implementing effective testing schemes reaching maximum population (The Guardian, 2020; The Guardian, 2020; The Guardian, 2020; GOV.UK, 2021; BMJ, 2020). Based on these perspectives, this research used the questionnaire, which has both closed and open ended questions, to collect data from travellers who need to quarantine on arrival in England. This aim of the research is subjective. It employed an interpretivist view emphasised on the reality based on personal life experience (Kelemen & Rumens, 2008). The questionnaire used the semi-structured interview to that effect allowing a flexible approach to understanding those experiences of the travellers (Saunders et al., 2012). This subjective nature of the research, thus, adopted a qualitative method allowing the researchers to understand the thoughts, experiences and feelings of the travellers (Willig, 2013) regarding the testing kits scheme. Based on the opinions of Collis and Hussey (2009) and Saunders and colleagues (2019) Strauss, the research methodology required an inductive analysis. Accordingly, the research involved reading the data and conducting analysis. The researchers then made notes that are developed into themes and concepts and categories to identify similarities or differences, or contradictions or correlations between the experiences of the travellers. This was possible based on the formulation of the questionnaire to that effect. The questionnaire result shows that the majority of the participants (62.7%) were full time workers followed by 14.9% full time students working on a part time basis. The questionnaire result found three categories of participants who travel abroad. 56.7% of them who live permanently in the UK, travel occasionally abroad for holiday or visit their families, followed by 9% of those living permanently in the UK who travel abroad for work and 7.5% who live permanently in the UK and travel abroad occasionally for other reasons.

The figures above are relevant to seek to obtain a subjective understanding of the participants regarding the supply chain effectiveness of the Test to Release Scheme. When asked the number of time they have travelled abroad since the introduction of the Test to Release scheme (15 December 2020), it was only 1.6%, which is one person each who had travelled 5% or more than 5%, followed by 32.8%, who travelled abroad once, 21.9% who travelled 2 times and 15.6 times who travelled 3 times. When asked the number of times since 15 December 2020 that they were quarantined on arrival because they were unvaccinated or had been in a country or territory on the red list in the 10 days before your return trip, 53.2% responded that they had quarantined 1 time, 19% responded 2 times, 6.4% responded 3 times and 2.1.% responded more than 5 times. 19% of them were vaccinated. When asked the number of times, since 15 December 2020 that they have participated in part in the Test to Release UK scheme to end your self-isolation earlier, 47% responded 1 time, 26.3% responded 2 times, (2.6%) (1 person each) responded 3 and 4 times. However, the response also shows that 21.1% (8 people) did not participate at all. This 21% either shows that the scheme has not reached them, or as earlier question shows that 19% of them were vaccinated or exempted from quarantine, there is still a difference of 2%, which definitely shows that they have not availed the testing scheme. The questionnaire result shows that the majority of the participants (86.7%) availed the testing at home. It is only 1% that did the testing sometimes at home or in a clinic or at the airport. The 3% testing at the airport also shows a potential strategy that could make traveller easily avail the testing scheme. The result also shows the crucial role play by digital health strategy where 96.3% of the participants access the testing scheme through the provider’s website and 3.7% through their mobile app. Question 21 evidence the important role digital technology occupies in the health and care sector. It has provided multiple providers that provide the digital enable services to access the Day 5 home-based test kit. It is further evidenced by the majority 29.6% who have access to other service providers. This also means that other than the commonly used provider’s platform as listed in the questionnaire, there are multiple other players (see Q. 21.a). The reasonable cost of availing the service is the prime reason for choosing a particular service provider. Thus, on being asked why they have selected the Day 5 Test to Release providers, 51.9% responded that they are the cheapest. 18.5% , which is the second majority, shows that the services were recommended by family and peers evidencing that awareness of the provider is also essential. Another 18.5% responded that they have chosen randomly, which shows that the service is easily available. Moreover, 22.2% and 59% of the participants were extremely satisfied and satisfied respectively with placing the order. Similarly, 55.6% and 18.5% reported being satisfied and extremely satisfied respectively with contacting the provider. However, 7.4% and 11.1% reported being very dissatisfied with both the items. Also, 11.1% reported being very dissatisfied with both the items. A similarly consistent result was with the availability of the test kits under sale with 51.9% and 18.5% being satisfied and extremely satisfied and 11.1% being very dissatisfied and dissatisfied. The result is around a similar percentage when it comes to delivery options and guidance for returns.

Supply chain functions effectively when there is an adequate flow of real-time information, materials and appropriate measures providing visibility (Ageron, et al., 2020). Question 24 is relevant with this aspect. Thus, when asked from where participants ordered the Day 2 and Day 8 tests when purchasing a home-based Test to Release Day 5 test, 55.6% ordered it from the same provider followed by 14.8% who ordered it from different providers. 48.1%, a majority of the participants, used the Royal Mail, a non-private centralised entity, showing travellers main preference of logistics. Similarly, they have also used similarly organised logistics, DPD and DHL (18.5% each). The logistics had door delivery with 77.8% being delivered in that manner. Others were delivered through mailboxes. The testing scheme requires visitors from countries that are not on the UK's red list to take a private test 5 days after arrival and can end quarantine if the result is negative. Otherwise, people can quarantine themselves for 10 days. The test results may be returned between day 6 - 8 of the quarantine period. In that regard, question 27 and question 28 are relevant. When asked when the test to release kit was delivered to them, 44.4% responded between Day 1 and 4, 25.9% before arrival, 22.2% on the day of arrival and 11.1% between Day 6 to Day 11. This means that the delivery timing is not consistent. 63% responded that the kits never arrived on time (after Day 5) followed by 25.9% and 11.1% who responded that it arrived on time. Majority of the travellers dropped off the sample themselves at either a priority mail box (51.9%), standard mailboxes (18.5%), a parcel locker (7.4%), or a testing site (3.7%). 22.2% got their sample collected from their home by the provider’s courier. The use of technology in the health sector is predominant with all the participants receiving their result either through a mobile app (18.5%), email (81.5%), or a text (33.3%). Unlikely, 7.4% received it through post, majority of them (74.1% for Day 5 test, 66.7% for Day 6, 59.3% for Day 7, 63% for Day 8, 85.2% for Day 9 test, 77.8% for Day 10 test, 85% after Day 10 test) did not received the result on the same day. This also meant that the remaining received their result in time, which also meant that they reduced their isolation period. Question 37 evidenced this with 77.7% confirming it. The self-posting of test samples and the delay in the test results evidence that there are transport challenges. Thus, Question 36 relating to the difficulty in participating in the release scheme had a range of responses, including majority of them (59.3%) stating that the tests were expensive; 11.1% each stating either that drop off locations for the sample were too far from the self-isolation location, own arrangement to collect the sample, delayed delivery of sample sent, test did not have use-instructions and other such reasons. 7.4% responded that the test was out of stock and hence could not order. 3.7% of them received the wrong test. 18.5% responded that the result was produced late by the provider. While several providers are available, as seen in Question 21, responses in Question 38 mentioned participants’ recommendation to increase the providers to avoid short stocks (44.4%) and logistics that could collect and deliver kits and samples (22.2%); to create a common platform (22.2%); provider clear information on accreditation of laboratories (22.2%), to provide government-run platform regarding providers and laboratories services (29.6%), tightened regulation over practices of providers (22.2%), to cap the price (63%), and to increase drop-off locations (25.9%).

Question 39 was an open-ended question asking participants to share their experience of using the UK Test to Release scheme. One participant responded that the service should be reliable and avoid delays. On being asked in Question 40 the main reasons for not taking part in the Test to Release scheme to end your compulsory quarantine earlier upon your return in England, the response shows 62.5% of the participants citing costly testing to avoid participating in the Test to Release Scheme. 25% of them was not aware of the scheme. 25% preferred the quarantine.

4.2. Discussion

The purpose of this section will be to discuss and bring together the results from the literature review and the research findings. The summary of the literature review findings suggests that risks to supply chain could be environmental, organisational and network-related factors. Thus, even when there is an implementation of a digital system in the supply chain, there is still the issue of digital exclusion arising from inaccessibility, lack of skill and non-users (Kochan, et al., 2020; Underwood & Shelbourn, 2020; Watt, 2020; ONS, 2019). Such a gap represents a gap in supply chain project management (Benzidia & Fabbri., 2016). Starting with this assumption of a gap in the supply chain, this research conducted the questionnaire-based study to analyse the experiences of participants with the Test to Release scheme in order to reflect the current position of the supply chain management regarding Covid-19 testing kits. The sample of participants with majority of them (working full time) having travelled at least once since the introduction of the Test to Release scheme would give the impression that they would have availed the testing scheme to reduce their quarantine to get back to work sooner. However, it was only 78.5% collectively that have participated in the testing scheme. The gap of the remaining percentage may suggest project organisation issues, as (Bentahar and Gunasekaran, 2020; and Ageron, et al., 2020) put it, in the form of deficient real-time information, appropriate measures, visibility in the supply chain, or flow of the testing materials. The literature review suggests that there is a disruption of the supply of critical test kits from the drug company Roche (Griffin, 2020). This situation represents that the UK may be following, as (Hahn, 2020) stated, the problem-driven approach. This is evidenced by the literature finding that there is a supply crunch of the testing kits in the UK and the Question 21 and 21a responses that show the UK has not followed a lean supplier selection, which (Christopher, 2004; Tomlin, 2006) highlighted, where there are multiple service providers that are not coordinated and centralised with the possible aim that maximum providers may be able to address the supplies. However, the shortage of the stocks, as shown by Question 38 response, evidences that the approach is merely a short-term aim. The literature review and the research findings highlight the predominant use of technology in the health sector. This is evident when the participants placed order through the service providers’ website and mobile app (96.3% through the provider’s website and 3.7% through their mobile app) and the test result delivered using either through a mobile app (18.5%), email (81.5%), or a text (33.3%). These findings align with the literature review findings that the Covid-19 pandemic has shifted the mode and manner of communication transformation through the use of technological apps and platforms (Carroll & Conboy, 2020; Hellewell, et al., 2020). Digital application is meant to communicate and make aware of the ways to prevent diseases, which in this case is regarding the testing scheme (Dwivedi, et al., 2020; Pedersen & Ritter, 2020). Both the questionnaire findings and literature review findings expose the advantages and the challenges in execution and management of information flow and implementation of the testing scheme. On one hand, the participants were able to access the providers’ website or mobile app to place their order or to receive the result. On the other hand, a minority of them, based on Question 40, was not aware of the testing scheme (25%) or received the test result through post (7.4%). Material, financial and information risks could disrupt a supply chain and hence, there is a risk management need governing supply and demand, processes and operations. The risk management should have a wider coverage of factors that could cause (Christopher, 2004; Tomlin, 2006; Chopra & Sodhi, 2004). The questionnaire findings show multiple factors or risks disrupting the supply of testing kits, sample collection, and delivery of test results. For instance, inconsistent delivery timing of the kits (question 27 and question 28); the 63% response that the kits never arrived on time (after Day 5); or the delayed delivery of sample sent is a material flow risk. This contradicts the satisfied experience of the participants while placing the order or contacting the provider (22.2% and 59% - extremely satisfied and satisfied respectively with placing the order; 55.6% and 18.5% were satisfied and extremely satisfied while contacting the provider). Absence of use-instructions and other such reasons (Question 36) is a risk related to information. Costly tests is a financial risk (Question 40). The presence of all these factors indicates that there may be a deficient resource and capacity management.

Resource and capacity management relies on suppliers or distributors that could provide continuous supply even at adverse conditions. The resource and capacity management strategy should have an alternative set of suppliers and transport to mitigate risks of supply disruption. (Basu & Wright, 2010; Gadde, et al., 2010; Meyer, 2021). An effective management is crucial given the real-time (quicker and agreed timeline) demand of customers. This means that the service providers should have the ability to address any risks to the supply chain in terms of their capacity and resources (Christopher, 2014, pp. 7-10). While these may be the essential requirements in the capacity management, the UK Test to Release Scheme does not seem to show its capability in that regard. This may be true considering the inconsistent timing of arrival of the testing kit and more particularly with respect to capacity to conduct the tests and return the test result on a real time basis. The questionnaire responses are evidence. For instance, 7.4% of the participants responded that the test was out of stock. 3.7% of them received the wrong test. 18.5% responded that the result was produced late by the provider (Question 36). This is supported by the findings that 2020 also showed short in testing capacity with less than 10,000 people tested on a daily basis; 400,000 PCR tests conducted out of the 711,744-testing capacity; use of half the capacity which is 40,000 tests a day; or the lack of expertise of the private firms, such as Delloitte, to run testing (The Guardian, 2020; The Guardian, 2020; The Guardian, 2020; GOV.UK, 2021). Considering the challenges and issues so far, it could be stated that the Test to Release scheme is under a bullwhip effect. Two major causes among the four causes stated by Lee and colleagues (1997) and Campuzano and Mula (2011) may be particularly relevant. In relevance order, firstly, the third cause that involves an increase in orders by customers when there is scarcity seems to be relevant here. The questionnaire findings show that there were 7.4% of the participants that could not order due to test kits being out of stock. Further, the delay in production of the result, the inconsistent delivery time, inability to deliver kits on time, and other such delays show the scarcity in terms of the kits, capable service providers, and capable logistics that could meet the agreed or quicker real time delivery. Secondly, the first cause may also be relevant where it seems the decision making stakeholders have taken a rational decision to manufacture and supply the testing kits and make access possible for private testing. However, the challenges and issues so far identified evidence that the effort is sub-optimum where the demand forecasts and inventory are not matching. The mismatch between the demand and inventory may also be related to the capital management. This research has not delved into this aspect. However, an inquisitive approach into the findings, both literature and questionnaire findings, may present a deficit in working capital to purchase the kits and services of testing, including collecting, delivery and testing. On one hand, it could happen that the accounts receivable days or preferable payment periods are not appropriate for the service providers incapacitating them to perform their roles timely. This may take a form of exploitation resulting from government procurement policy planning, which might have affected the overall supply chain’s overall financial wealth (Akkucuk, 2019; Peng & Zhou, 2019). On the other hand, the government is not granted more collection days, which deter sales and deny the benefit of lower costs testing (LucíaRey-Ares, et al., 2021). The research analysis suggests that the UK’s supply chain is not able to offer a competitive and profitable advantage. It lacks a centralised, collaborative approach as evidenced by the multiple number of service providers; the inability to deliver customer value as evidenced by the participants response that they drop off locations for the sample were too far from the self-isolation location (11.1%); they have to make their own arrangement to collect the sample; or that the test scheme is expensive and there is no cap (Questions 36 and 38). Both the literature review and questionnaire findings suggest that there should be a centralised system governing the procurement, selection of service providers, and logistics. The recommendations of the participants are aligned with the main challenges in or essential requirements of an effective supply chain. Recommendations in Question 38 include increasing the providers to avoid short stocks (44.4%); collection and delivering by logistics of kits and samples (22.2%); creating a common platform (22.2%); providing clear information on accreditation of laboratories (22.2%); providing government-run platform regarding providers and laboratories services (29.6%); tightening regulation over practices of providers (22.2%); capping testing price (63%), and increasing drop-off locations (25.9%).

Chapter 5 - Conclusion

This research has sought to identify and understand the critical challenges that have affected the supply chain of home-based Covid-19 test kits used under the Test to Release scheme. Accordingly, it investigated the major challenges with the purposes of recommending key insights that could inform policymakers to address the challenges. The main finding of this research is that the UK supply chain system is not collaborative and particularly not centralised. This is evidenced by the absence of a lean selection of suppliers and logistics management exposing the people to inconsistency in pricing, information, delivery and logistic activities. This has affected the supply chain activities causing a bullwhip effect. As (Vázquez, et al., 2016) put it, there is a short-sighted attitude that should be avoided in a cooperative supply chain. The main challenge seems to lie with the resource and capacity management that has not been able to address demand forecast and inventory challenges. As Tang and Musa (2011) stated, the material flow risk is relevant with the UK’s supply chain context. There is certainly a challenge in the sourcing, making and delivering stage. Financial issues do not seem to be the problem as the UK has invested billions of dollars to upscale the manufacturing. The inquisitive approach discussed in the discussion section seems to be relevant here that presented challenges in working capital management, including those of accounts receivable days or preferable payment periods (Akkucuk, 2019; Peng & Zhou, 2019; LucíaRey-Ares, et al., 2021). The solution may lie with the collaboration and centralisation approach, as both the literature review and the questionnaire findings suggest. Thus, in the recommended model, the financial and operational processes are considered together. This model will focus on an end-to-end solution applicable to the sourcing, delivery, logistics, capital, resource and capacity management, risk and inventory management, supplier selection, and platform administration guided primarily by customer value followed by a competitive and profitable advantage to all the stakeholders. Firstly, the model is data driven and not problem driven. As a simple example, the questionnaire findings suggest the main challenges and essential policy recommendation. Hence, the model should focus on collecting, analysing and applying data and their findings. Secondly and accordingly, the model should be a centralised, integrated digital solution. This solution encompasses many aspects. This may include expanding the capability of creating awareness and increasing accessibility to services, including creating a national guidelines and instructions about the Test to Release scheme, its uses and mode of access. It may include creating a central entity that retains the power of procuring and distribution bargaining positions between the other stakeholders (service providers, laboratories, logistics, etc). It may include creating and using one national website and one mobile app, or in additional an alternative website and app. Such centralised system is a representation of a collaborative approach, centralised and decentralised. One entity to regulate the entire supply chain. The central authority or entity will be empowered to lay down required credentials, capacity and qualification to become authorised providers, whether testing services or logistics. This will ensure a lean selection mechanism. The list of all the authorised providers will be listed in the centralised website or the app. Together with this, the central authority or entity will also set the financial and other operational terms. It will set the cap price and its terms and conditions. It will also set the commercial terms in terms of cost collection and payment, delivery of supplies, and logistics terms. For example, the central entity, based on a data-driven analysis, can forecast demands and place the order from the suppliers. Depending upon the capacity of the suppliers, the supplies will be distributed. A competitive bid mechanism can be in place. The determination will be based on other key factors. They could be based on the timelines concerning production, transport and collection, transport and delivery of testing kits or results. Alternatively, there could be separate private-public partnership including the local suppliers in order to mitigate any risks of supply chain disruption. All such agreements and terms must be subject to the resource and capacity qualification, one being e-communication platforms to collaborate with the centralised system. The determination should also consider the combined capability of manufacturing, testing, and logistics or at least a combination of two of the three qualifications. A data-driven centralised approach may enable locating relevant information and positions of the supply chain. The relevant stakeholders can take informed decisions based on the terms and conditions, building an interdependent, connected and collaborated supply chain. This will drive customer value and also competition amongst the stakeholders. Deriving from recommendation by the participants in the research, the central authority must regulate the supply chain actors and their roles and enforce the supply chain terms and conditions agreed upon. While conducting this research, the researcher understood that supply chain management is a dynamic and very complex structure. It is very subjective given that there are multiple factors, that are inherent and external to the chain having equal impact in the chain management. The vastness in the understanding of the relevant concepts made the researcher realised the limitation in the formulation of the questionnaire itself. For instance, Qs 23(1),(2) and (3) show dissatisfied participants. This could have been linked with Q24 that shows that Day 2 and Day 8 order from different providers by asking whether this was caused by the dissatisfaction. Understanding supply chain management requires a holistic approach, which the researcher understood that the research needed a holistic approach, which may be lacking in this research to a certain extent. To conclude, the solution depends on the ability to construct a centralised system, which could implement and enforce an agreed supply chain model. Collaboration may merely bring the actors in a network. Having a centralised structure in place will enable collaborative fulfilment of the model recommended in this research. The UK’s supply chain related to the test to Release scheme is exposed to financial and operation risks. Unless they are understood and address through the centralised model, the issue of scarcity of testing kits, bullwhip effect, unequal power distribution between the service providers and the government agencies, the short-sighted gains cannot be converted into long-term gains.

Bibliography

Abedrabboh, K. et al., 2021. Game theory to enhance stock management of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) during the COVID-19 outbreak. Plos One, 16(2).

Ageron, B., Bentahar, O. & Gunasekaran, A., 2020. Digital supply chain: challenges and future directions. Supply Chain Forum: An International Journal , 21(3).