Water Scarcity in Saudi Arabia

Chapter 1: Introduction

1.1: Background and the current Saudi situation

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) has an area of about 2.25 million km2 with a total population of about 30 million (Ouda, 2013). The scarcity of fresh water resources is a major challenge facing Saudi Arabia (Mahmoud and Alazba 2016a), this scarcity is threatening the economic development and political stability of many parts of the Middle East. KSA is one of the hottest and driest subtropical desert countries in the globe. With an average of 112 mm of precipitation per year (Mahmoud and Alazba 2014), much of the Kingdom falls within the standard definition of a desert. Water management in the KSA is facing major challenges due to the limited water resources and increasing uncertainties caused by climate change (Mahmoud and Alazba 2016b).The exploitation of subsurface water from deep aquifers also depletes resources that have taken decades or centuries to accumulate and on which the current annual rainfall has no immediate effect (Mahmoud et al. 2014; Mahmoud and Alazba 2014). Water limitations are particularly severe in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The major item of water consumption in KSA is the agriculture sector about 20 billion m3/year by the year 2000 (Mahmoud and Alazba 2016b). The agricultural water demands were 83–90 % of the total water demands during 1990–2009 (Mahmoud and Alazba 2016b). To address the water conservation policy, KSA has adopted a strategy to reduce agricultural water demands by introducing modern irrigation techniques, which lead to a decline in consumption of water for agricultural purposes, at an average annual rate of 2.5 % between 2004 and 2009 (Mahmoud and Alazba 2016b). This agricultural expansion occurred as a result of rapid increases in population and human activity and the establishment of large-scale water projects such as dams and flood control infrastructure (Mahmoud and Alazba, 2015). Moreover, poor resource management resulted in the overexploitation of natural resources, with adverse effects on sustainable development. Land cover conversion has resulted in land degradation, interfered with biodiversity and the ecosystem, and caused water stress (Mahmoud and Alazba, 2015).

Since the early 1990s, the concept of Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) has been known throughout the world (Mitchell 1990,2005; Dublin Statement 1992; Jønch-Clausen 2004; Swatuk 2005; Medema et al., 2008; Jeffrey and Gearey 2006; Cook and Spray 2012;Medema and Jeffrey 2005). IWRM is based on the perception of water as an integral part of the ecosystem, a natural resource and a social and economic good, whose quantity and quality determine the nature of its utilization (Al Radif 1999;Pahl-Wostl et al., 2007; Pahl-Wostl et., 2011;Butterworth et al.,2010; Mostert 2006; Petit and Baron 2009; Giordano and Shah2014). This approach incorporates policy options that recognize these elements, develop national water policies and base the demand for and allocation of water resources on equity and efficient use (Al Radif 1999; Petit and Baron 2009; Giordano and Shah 2014). In order to implement IWRM, It may be necessary to consider the strengthening of human resources development in terms of awareness creation programs, training of water managers, the development of new institutions that will serve and match this goal, effective information management, environment and development, the integration of water planning into national economy and financing and scientific means (Jønch-Clausen 2004;Swatuk 2005; Medema et al., 2008; Jeffrey and Gearey 2006; Cook and Spray 2012; Medema and Jeffrey 2005).

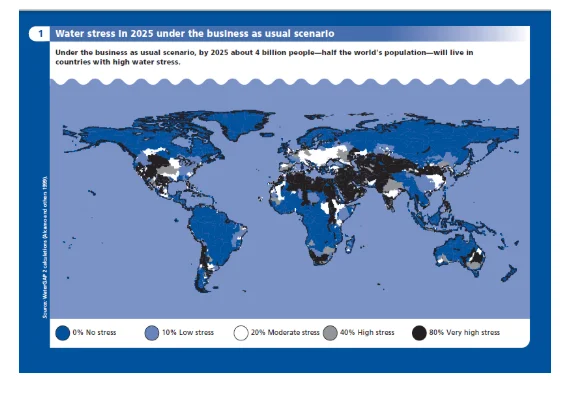

On the national level, there is a few studies which have been conducted to measure the public awareness of water shortage through the promotion of IWRM. For example, Ouda (2013) designed a study to measure the public awareness of water shortage problem in Al Khobar City at the Eastern Province of KSA. Results from this study showed low-level of water shortage awareness among respondents (Ouda 2013 Ouda et al., 2013). Therefore, it is necessary to increase the public awareness of water shortage problem (Ouda et al., 2013). Another study conducted by Cosgrove and Rijsberman (2014) revealed that Saudi Arabia will face water stress, or scarcity conditions by 2025. The authors stated that the ratio of withdrawals for human use to total renewable resources (the criticality ratio) implies that water stress depends on the variability of resources, and this ranges from 20% for basins with highly variable runoff to 60% for temperate zone basins, with an overall value of 40% used to indicate high water stress. In order to overcome water scarcity, the officials and legislators of water resources in Saudi Arabia have encouraged the promotion of rainwater harvesting to avoid the suffering associated with severe drought (Mahmoud 2014).

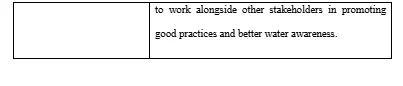

The population of Saudi Arabia has tripled since 1975, leading to an ever increasing demand for water despite the scarcity of acceptable quality resources. From the Central Department of Statistics and Information in Saudi Arabia, the total population is 28,376,355 according to the 2011 census. In addition, growth in the industrial and the agricultural sector has led to an increase in demand alongside excessive water pollution. Figure 1 shows high levels of water stress. Mahmoud (2014) reported that agriculture water use in KSA is almost completely dependent on groundwater, which is difficult and expensive to obtain. While, water for domestic purposes has to be obtained by desalination, which is a cost-intensive process. Alternative supplementary water sources such as rainwater harvesting, wastewater reuse and desalination were introduced in several studies in the last decade (Mahmoud and Alazba 2016a, b; Mahmoud and Alazba 2015, Amin et al., 2014a, b; Amin et al.,2015). As a result of that, KSA have established more than 360 rainwater harvesting dams (Mahmoud and Alazba 2016a, b). Some of the largest of these dams are located in the Wadi Jizan, Wadi Fatima, Wadi Bisha and Najran districts (Figure 2).

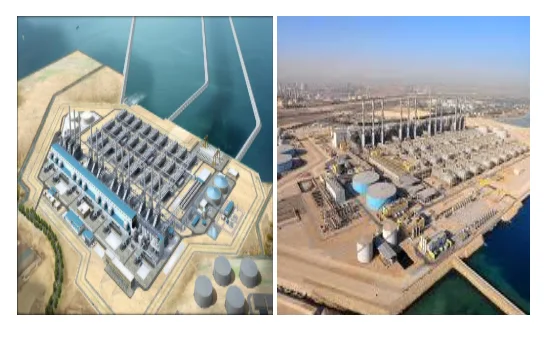

The king Fahad dam in Saudi Arabia on Wadi Bisha is the biggest dam in the KSA, and considered to be the largest concrete dam in the Middle East. Regarding desalination plants, there are approximately 40 desalination plants, 27 of which are operated by The Saline Water Conversion Corporation (SWCC) which produces more than 3,000,000 cubic meters a day of potable water. Water is purified through a Multi Stage Flush (MSF) System and Reverse Osmosis (RO) (Bushnak, 1997). The world’s largest independent water and power plant (Figure 3) (IWPP); has 2,745 megawatt power capacity and desalination output of 800,000 cubic meters per day, considered the world’s largest integrated water and power project facility.

The IWPP with its 2,745 megawatt power capacity and desalination output of 800,000 cubic meters per day, is considered the world’s largest integrated water and power project facility. Recycling plants in Riyadh and Jeddah have also supplied up to 40% of the water required for domestic usage in urban areas (Al-Zahrani, 2009). Through these different methods of supply, although people have enjoyed an improved quality of life, it has caused environmental destruction to a magnitude that cannot be predicted (Buchholz, 1993; McNelis and Schweitzer, 2001; Aburizaiza et al, 2013; Ulrichsen, 2013). In support of this, the United Nations World Water Assessment Programme through the UNESCO organisation (2009) has demonstrated that the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (still one of the developing countries in providing villages and settlements with urban water system services such as sanitation water systems and potable water distribution networks). The Saudi government made strong commitment to support long term and sustainable development of freshwater resources against challenges of increasing demand, potential water quality deterioration, limited availability and future impacts of climatic change at all levels. To cater the above challenges, the government adopted rational approach to utilize groundwater resources by controlling aquifer development, well licensing and drilling, agriculture policy modification, production of non-conventional water resources, fully utilization of surface water resources and effective water conservation and efficient demand management (Mahmoud, 2014). Recently, Ministry of Water & Electricity has implemented very ambitious nationwide water conservation program for efficient use of water which was focused on Water Demand Management (WMD) for domestic and non-domestic customers, organizational restructuring and progressing towards privatization which resulted significant reduction in water consumption.

Suleymanova (2002) explained that the Water Scarcity where water supplies are inadequate, two types of water scarcity can be identified that particularly affect developing countries as follows: Physical Water Scarcity and Economic Water Scarcity. Saudi Arabia shows Physical Water Scarcity in that water consumption exceeds 60% of the usable supply, and the Water supply therefore is insufficient to meet the demand of agriculture, the domestic and the industrial sectors in addition to satisfying environmental needs (Suleymanova, 2002). Also Suleymanova (2002) has shown that, in order to help meet water needs some countries such as Saudi Arabia and Kuwait import much of their food and invest in desalinisation plants which increases the cost of water to around twice that of the UK. In addition, Suleymanova (2002) revealed that Economic water scarcity when a country physically has sufficient water resources to meet its needs, but additional storage and transport facilities are required.

1.2: Aims and objectives

1.2.1: Rationale for this study

In light of the current situation in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, particularly the rising demand for fresh water and the limitation of its supply, public awareness campaigns have proved to be an effective tool in effecting behavioral changes amongst the public, using different marketing and media tools to spread the message of water conservation (Ouda et al.,2013; MOWE 2012). The campaign included production and transmission of many conservation massages via television, radio, and newspapers commercials. It provides with far contents and targets. However, more efforts need to be done through public awareness campaigns as recommended by Ouda et al., (2013) to promote integrated water management (IWM). An interdisciplinary integration of society, water politics, education and economics will be required in order to move away from the existing system of water management that depends on an ever-increasing supply, into a modern urban system such as installation of water saving devices such as constant flow regulators and low capacity flushing toilets; highly efficient sanitation and irrigation equipment, public education and publicity programs on the importance of water conservation; and pricing water to reflect its strategic importance and scarcity value (MOWE2012; Ouda 2014; Ouda et al., 2015). To achieve this new and important shift, we should initially focus on the realisation of integrated urban water management because by 2015, 91% of Saudi population will be in urban areas as estimated by Global Water Intelligence in the Pinsent Masons Water Yearbook 2009-2010.

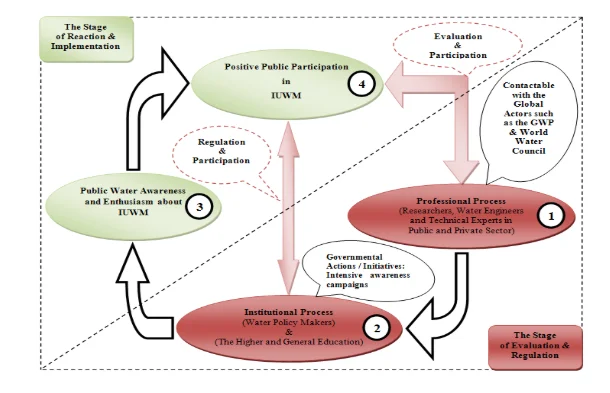

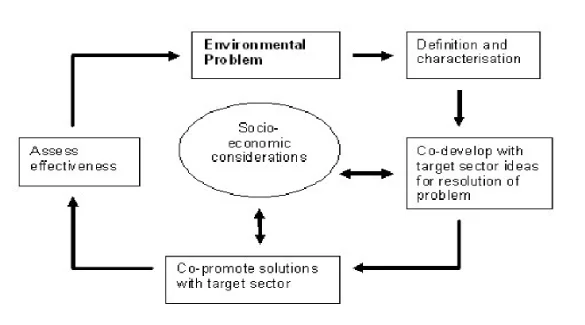

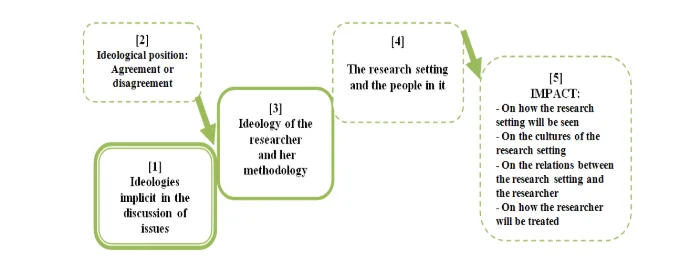

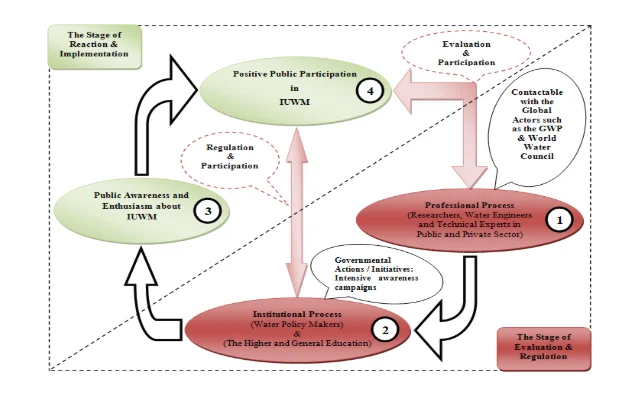

Figure 4 demonstrates how gaining further knowledge on the potential for public engagement’ (the evaluation of public awareness, current activities from water managers, water engineers, water planners and water researchers) could operate as the essential first stage in a process that will provide the basis of a new paradigm for enhancing the integrated urban water management. The second stage shows the reaction to (and the implementation of) new plans and suggestions for the active participation of the public and other stakeholders. In this way a dynamic loop is created by this continual dialogue, the foundation of which will be the comprehensive, original study provided by this research. In the course of this thesis, Figure 4 will be presented as a new paradigm for the provision of integrated urban water management, making optimum use of public participation which will then be converted to positive behaviours with respect to water conservation.

1.2.2: Research questions

The main research question of this study is, to reiterate: To what extent Integrated Urban Water Management in Saudi Arabia can be enhanced by positive stakeholder/public participation and public awareness?

In order to fully address this question, the following sub questions have been formulated:

1. What is the current level of public awareness of water issues?

2. How much public engagement is likely?

3. How and to what extent can public engagement be stimulated to enhance integrated urban water management in KSA?

4. How and to what extent can public engagement be harnessed to enhance integrated urban water management in KSA?

This research aims to make significant contribution to knowledge through a comprehensive survey of water awareness and positive public participation in integrated urban water management (IUWM) in Saudi Arabia. The research will be carried out through analytical interpretation of data provided by recent original surveys. Through investigating the existing practices and visions of all stakeholders in relation to integrated urban water management applications, a clear picture of the current situation will be formed. This investigation, and its potential for utilising the active participation of the public and other stakeholders, will be an essential foundation for all Saudi society to participate in the implementation of IUWM. It is for this reason that the research will focus on socio-political, economic and cultural aspects.

The main aim and objectives

The overall aim of this research project is to determine the extent to which Integrated Urban Water Management can be enhanced by positive public participation and public awareness. To address this (the main aim), the following objectives are the guidance and roadmap towards achieving the main aim of this study.

Objective 1: Explore current water supply and management systems in Saudi Arabia.

Objective 2: Identify the current level awareness of water issues among the selected stakeholders in KSA.

Objective 3: Evaluate how selected stakeholders influence public awareness to enhance the implementation of Integrated Urban Water Management in KSA.

Objective 4: Evaluate how much public engagement is likely for enhancing the IUWM.

Objective 5: Establish how and to what extent can public engagement be stimulated and harnessed.

1.3: Structure of the investigation

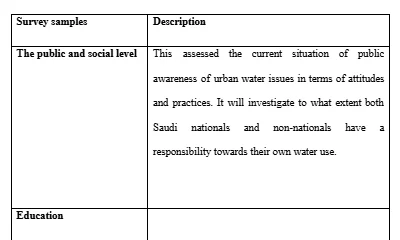

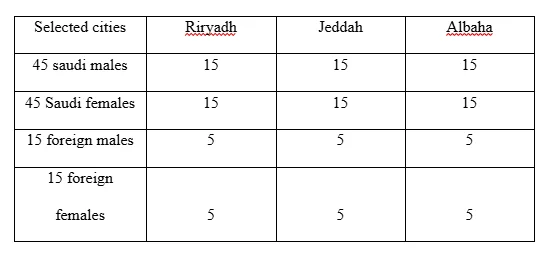

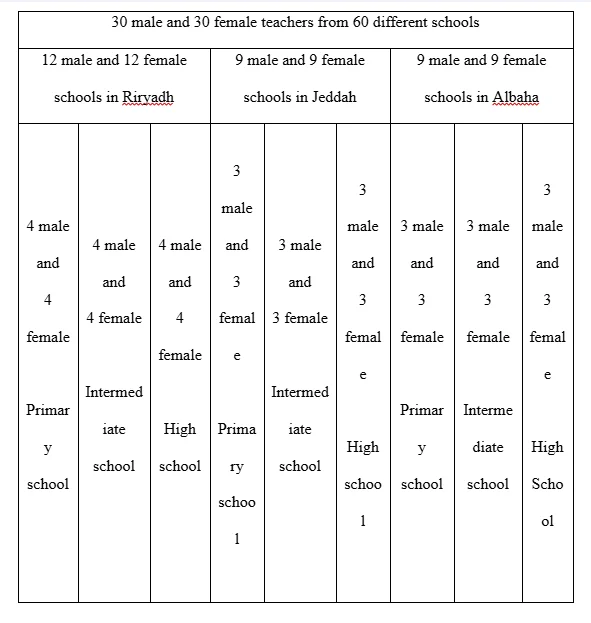

The thesis was structured on the following sections: chapter one is the introduction, chapter two is a literature review of both integrated water resource management and integrated urban water management within KSA. Chapter three discussed the appropriate methodology used for this research Once the rationale and need for this research was established in chapter two and three, an overview of water management was set the scene for a new primary source material; which was discussed in depth in chapter four. New data obtained from both primary and secondary research. The primary research data was obtained by conducting interviews in the UK and distributing questionnaires in Saudi Arabia to three groups of stakeholders such as teachers, lecturers, water managers, engineers and environmentalist who all have valuable insight on this topic and can share their thoughts and views on expansion and development. The questionnaires were established in English then, they had been translated into Arabic, and after the analysis the Arabic quotations were translated into English and the original Arabic are listed in the Appendix. The researcher visited the KSA in order to distribute and collect the questionnaires. A total of 220 respondents participated and filled and returned the questionnaire in Saudi Arabia. In the UK, the researcher interviewed water managers working within the UK water industry. The interviews lasted between half an hour to an hour. All answers were recorded so accurate and relevant information can be obtained. Next, the researcher used a focus group to fill out surveys in order to ascertain the effectiveness of the research questions and to fulfill the study aims and objectives. The surveys were tested on 10 students in the UK before being distributed to professionals. All students have a background in water management. The results of the pre-test were positive. The method of analysing the interviews is totally qualitative. The questionnaires consisted of both quantitative and qualitative analysis based on the nature of the questions. In reality, the analysis of the majority of surveys questions was made through coding, thematic and interpretative analysis as a qualitative method. Chapters five, six and seven analysed the answers obtained and the main research questions were answered (see Table 1):

In the table 1 above, the answers to the main research questions obtained after carrying out an analysis have been summarised. As depicted in the table, survey samples for the study were obtained from a various levels including the public and social level, education, academia, institutional level, environmental and industry. The wide range of sample levels suggests that the data and results obtained in this study are more reliable as they cover diverse levels of the population. Following the analysis and discussion of the extensive surveys, successful models from the United Kingdom has been analysed with respect to their success in building public engagement and participation. Using the results of the UK campaigns as a model of how awareness and good practice can result in significant improvements in water conservation has been developed and discussed in chapter seven in the light of how it may provide a model that can contribute to IUWM.

In chapters eight and nine, paradigms of water conservation, recycling and environmental awareness has been compared in order to enable the formation of a new paradigm for an effective Integrated Urban Water Management system (Figure 4) which will be tested against the major research question of this thesis. It will be shown how the new database that was presented and discussed in chapters five and six is essential for the operation of the proposed paradigm. Finally, the conclusions of the research have summarised its contribution to knowledge, and make suggestions for further research.

Chapter 2: Literature review

2.1: Water Management in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

This thesis began with a short account of the current Saudi situation with respect to how diminishing water resources must cope with an ever increasing demand. An analysis of this demand for water will follow, detailing how different social groups impact on water availability. The second section of this chapter will then provide a comprehensive overview of how this demand for water is currently managed in Saudi Arabia, with an assessment of current practices of integrated urban water management.

2.1.1 Water Demand in Saudi Arabia.

In Saudi Arabia, there are several types of water uses which are mainly prioritised according to the Islamic Laws. They are as follows: domestic use, animal watering, agricultural use, industrial use and finally recreational use. Giansiracusa (2010) however points out that because renewable water resources are decreasing at an annual rate of 2%, the current level of consumption is unsustainable. Giansiracusa goes onto explain that in 2010, Saudi Arabia's renewable water capacity was only one quarter of the global average. The situation would worsen due to population increases that the World Bank forecasts will rise to 31.6 million in the next decade. Giansiracusa goes on to explain efforts by the Saudi government to save water by reducing wheat production in addition to investing in desalination technology and discussing how to reduce subsidies. In the late twentieth century, a program to make the Kingdom self-sufficient in wheat had led to almost 85 % of water being used for agriculture. Now prepared to face the problems of non-sustainable water resources, the government aimed to phase down its agricultural subsidies in order to cut wheat production annually by 12.5% over an eight-year span, so that by 2010, farmers had cut planted areas by 40% (Giansiracusa, 2010). Figure 24 shows the overall growth in Industrial, domestic, and agricultural water demands in Saudi Arabia:

According to Gasson (2011-2012) director of the Sustainable Water Alliance for Severn Trent Services, the third largest consumer of water per capita in the world is Saudi Arabia, which is significant in view of its renewable water capacity being only 25% of the global average. A reversal of this trend is expected in the future, however as Saudi Arabia is expected to become the third largest water user of recycled market in the world, after the United States and China. Gasson however also points that only 18 % of the 1.84 million m³ of wastewater processed every day by the KSA, is reused at the present time. Al-Zaharani, Al-Shayaa and Baig (2011) emphasised the urgency of developing conservation and managing demand in order to create a balance between need and availability. To paraphrase, focussing on the management of water demand instead of developing ways of increasing the supply should lead to a much improved use of resources. They also pointed out that efficiency can be improved among non-domestic users through developing technologies and education initiatives. In Alriyadh newspaper, Alshibl (2012) stated that the rapid increase in urbanisation in the city of Arriyadh was leading to an increase in demand at the same time as reducing the availability of the water supply. A contributing factor was also the volatile weather in the capital, including sandstorms and dust clouds. A few days later, by the Riyadh Business Unit Director in the National Water Company (Eng. Nimr Muhammad Alshibl), also in Alriyadh newspaper, Alshibl (2012) reported that Arriyadh (the capital city of KSA) had one of the highest rates of water consumption in the world. It confirmed the MWE’s estimate in that consumption could reach 330 cubic litres per person, where in the other capital cities, the average usages between 120 cubic litres and 220 cubic litres daily. The report continued with suggestions for domestic users to check for water wastage through leaks.

2.1.2: Identification and recommendations for water progress in Saudi Arabia

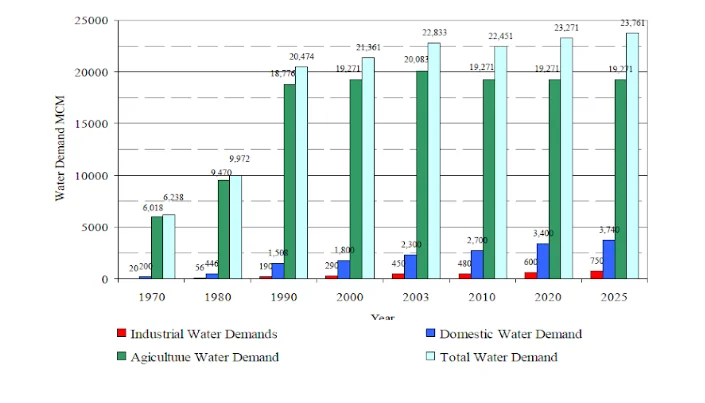

The following facts about the water sector are from the analysis paper Water and National Strength in Saudi Arabia, published in March 2011 by the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) - Middle East Program: The rapid development in the Saudi government and especially the water sector has been recognised by the international community. In 2001, the Ministry of Water and Electricity received four international awards for expert water management in an arid environment. Saudi Arabia accounts for about 30 % of global capacity. (figure 25) (CSIS, 2011) Data from the analysis paper will be paraphrased and diagrams reproduced, in order to explain the more significant facts about current water usage in the Kingdom.

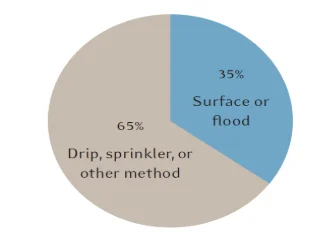

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia has twice the population of other Gulf Co-operation Council (GCC) countries, but the Government can provide around 50% more water per person than the average GCC region. By 2016, it is estimated that the wheat production will end in the KSA, making significant savings to the Kingdom’s groundwater supply, but future agricultural policies will need to be carefully considered to meet the needs of users at the same time as conserving water supplies. Irrigation technologies could be developed and improved because at present 35% of Saudi farmland is currently irrigated via traditional surface or flood methods (see figure 26), but the development of drip or sprinkler irrigation systems would yield a significant saving (CSIS 2011).

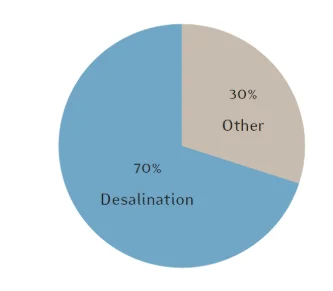

Desalinated water accounts for between 50 percent and 90 percent of the use of a typical Saudi city, seen in figure 27 below. However, it is currently a non-renewable resource requiring large quantities of energy through oil. At the moment the KSA can provide this, but in addition to the pollution issues from desalination plants, the use of oil is not a long term strategy as desalination already accounts for more than half of the kingdom’s domestic oil consumption,

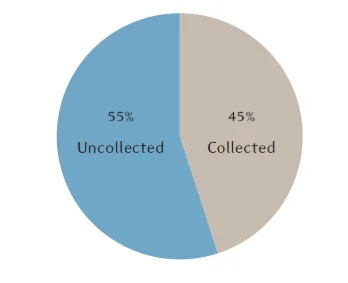

Significant savings could be made through an improvement of the infrastructure in order to collect, treat and reuse wastewater. This could be used for agriculture in order to relieve the demands on groundwater resources and reduce the use of desalinated water. Only 45 %however, of wastewater is actually collected, seen in figure 28 and an even smaller fraction is treated and reused at present.

With respect to the problematic issue of water pricing, consumers only pay about 1% of what it costs the government to provide water (CSIS, 2011). For the government to maintain current water provision in the face of ever increasing demands, it may need to consider raising tariffs or metering. In addition to the Kingdom investing in new technologies, metering would enable water use to be accurately tracked. Relevant data could then be stored for future reference. This has been a summary of the facts and recommendations from Water and National Strength in Saudi Arabia (CSIS, 2011). A discussion of what is actually happening to address the status of integrated urban water management in Saudi Arabia has been presented in the following Section.

2.1.3: The status of Integrated Urban Water Management (IUWM) in Saudi Arabia

Cosgrove and Rijsberman (2014) in their book Making Water Everybody's Business have revealed that by 2025 about 4 billion people will live in countries with high water stress, including Saudi Arabia and all of the other Arabic countries. They also quoted these statistics for the ratio of human use to total renewable resources which show that water stress is affected by the availability and variability of water sources. Indicating a value of 40% to indicate high stress, it ranges from 20% for basins with highly variable runoff, to 60% for temperate zone basins. The analytical paper Water and National Strength in Saudi Arabia, published in March 2011 by the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) - Middle East Program has provided an overview of the current situation of the water sector in Saudi Arabia. Although the Kingdom is rich in oil but has scarce renewable water supplies, the government has nevertheless succeeded in satisfying water demand through investing in desalination and domestic agriculture. The authors point out that many governments around the world would struggle to fulfil these needs. The paper also found that although the Saudi Government predicts that it will continue to cope with demand, there are several issues to address with respect to increasing water scarcity. It will be necessary to end wheat production by 2016 for example to ease the demand on groundwater resources. Geographical issues are a major part of the Kingdom’s problem according to Al-Zahrani and Baig (2011), who provide the following statistics of water use. The environment is arid and water resources limited, so as demand for fresh water increases, supplies will diminish until that they are no longer able to meet daily needs. Al-Kahtani (2012) has analysed the most important factors that could contribute to a rationalisation of domestic water consumption in Saudi Arabia. His results and projections are paraphrased in this section. Up to 11% of water consumers can be influenced by water conservation campaigns organised by the Ministry of water and Electricity, but more than half the population, 58%, are not yet influenced by campaigns. Al-Kahtani believes that a policy that encourages consumers to limit use is not sufficiently effective in the short term, though presumably such campaigns would be part of a longer term strategy. A new policy is required to rationalise water use as quickly as possible. Some commentators have turned to Integrated Urban Water Management as an effective approach, but IUWM cannot be considered a short-term approach in itself as it is a complex, longer term strategy. It could be argued however, that IUWM has the potential to enable strategies for immediate reduction in usage, combined with a longer term approach to change people’s attitudes and behaviours to water.

Mays (2009) describes IUWM as a new approach to managing the entire urban water cycle in an integrated way, a key to achieving the sustainability of resources and services. IUWM incorporates all these factors: all water resources including surface and groundwater resources, the quality and quantity of water provision, the fact that water impacts upon other systems and finally the co-relation between water and social and economic development. In the Special Feature on Integrated Urban Water Resources Management (IUWRM), prepared by the Water Team for the Global Development Research Centre (GDRC) website, IUWRM has been defined as: A participatory planning and implementation process, based on sound science, which brings together stakeholders to determine how to meet society’s long-term needs for water and coastal resources while maintaining essential ecological services and economic benefits. (GDRC, available at www.gdrc.org)

The IUWM/IUWRM approach has the potential to deal with all water issues including the supply and conservation of water. The question therefore arises: What improvements could be achieved by applying the IUWM approach in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia? Al-Hussayen Abdullah (2007) revealed a number of statistics in support of the need for IUWM, including the fact that only 45% of all wastewater produced is actually collected and only 6% of treated water is being used. Also about 70% of drinking water needs are produced by thirty water-desalination plants serving forty cities (as we have seen, desalination is the largest provider of water for domestic use). This makes Saudi Arabia the world’s largest producer of desalinated water representing 30% of the global production. If the KSA is to become less dependent upon desalination, water recycling which is currently so under-used, becomes one of the important components of IUWM as confirmed by the ‘Bellagio Statement’ Sanitation Collaborative Council (WSSCC) in 2000. The ‘Bellagio’ statement claims that an implementation of its principles would create an urban water system more reliant on recycling principles. In this way, waste water would also become as resource as recommended by Bahri’s paradigm (2011) in which waste water was an integral part of a recyclable supply (figure 9). Treating waste would lessen the risk of contamination but it could be argued that the technology would need to be developed, particularly with respect to the use of chemicals. In 2009 the report from the U.S.A - Saudi Arabian Business Council for The Water Sector in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (2009), explained the history of Saudi water management since the 1950’s as a move away from surface water towards a dependence on desalinated water. The report reiterates that the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is the world's largest producer of desalinated water and the quarters of the Marafiq complex in Jubail is the world’s largest independent water and power project. In addition, Saudi Arabia will have one of the largest water pipelines in the world. It is explained that a transport system of more than 900 km will pump about 4 million cubic meters of water per day Jubail Industrial City into Riyadh. The report stresses how as water becomes an increasingly scarce resource, future water management will put increasing pressure on the water infrastructure, as factors such as industrialisation and urbanisation continue to come into play. However, it has been revealed that an average of 20% of water is lost because the twenty-five-year-old infrastructures already under strain and prone to leaks. Furthermore, tariffs are extremely low, at a rate of only $0.27 or SR 0.10 per cubic metre and the report recommends an increase in the tariff to as much as $1.40 orSR5.00 per cubic meter. Abu Zeid Mohammed, Abu Zeid Khalid and Afifi (2005) draw attention to the fact that in the Arab world, The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) is committed to support countries to achieve water-related targets from the World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD), in partnership with the Arab Water Council (AWC) and the centre of Environment and Development for the Arab Region and Europe (CEDARE). In Saudi Arabia, the ministry of Water and Electricity governs the water sector. It is ensuring that the action plan for the water sector strategy is in compliance with the UNDP requirements. The process has been prepared with the assistance of the World Bank and UNDP, and has been separated into three stages. The first stage, an assessment of the then current water resources management was completed in January 2004. The second stage is to develop water sector polices through extensive consultation and the third stage will be to develop an action plan for the implementation of this strategy. As this strategy will involve multiple partnerships and stakeholders, it will be an opportunity to implement integrated urban water management as a national strategy. Zaharani, Al-Shayaa and Baig (2011) as discussed in section above, called for the emphasis of water management to concentrate on rationalising demand rather than increasing the supply. In this respect, they raised concerns about the amount of water currently wasted by domestic users. They claim that over-generous subsidies have led to the false impression that water is a free resource and that all stakeholders including the policy makers, planners and consumers need to reconsider their attitude to water as a matter of urgency. In addition to increasing demands from all users, Al-Zahrani and Baig arrive at the conclusion that the available water sources will be unable to meet the requirements of ever-increasing population of the Kingdom. This state of affairs has led to the need for the enhancement of the Integrated Urban Water Management in Saudi Arabia. At present however, water management systems are not sufficiently co-ordinated to enable IUWM, so the optimisation of available water resources will be delayed. (Al-Zahrani and Baig, 2011) The concept of integrated urban water management is therefore a combining of sustainable water use with successful decision making processes. Marsalek, et al (2007) stated that ‘effective management of urban water should be based on a scientific understanding of the impact of human activity on both the urban hydrological cycle – including its processes and interactions – and the environment itself. Such anthropogenic impacts, which vary broadly in time and space, need to be quantified with respect to local climate, urban development, cultural, environmental and religious practices, and other socio-economic factors’.

Marsalek, et al (2007) place human action in the centre of IUWM as in Bahri’s paradigm (figure 9). In addition, the workbook for the Integrated Urban Water Management Approaches, prepared by the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) (2007), defines integrated urban water management in this way: ‘…although the use of individual tools clearly indicates positive steps towards its adoption, it does not mean that a utility is fully committed to IUWM. The IUWM approach requires not only the use of relevant IUWM tools, but also requires an understanding of the biophysical, social and economic implications of utilising these tools, taking suitable actions to mitigate any adverse effects and developing a highly coordinated and participatory approach to managing the water supply, wastewater and stormwater systems as a holistic system. Hence, one major change for IUWM is the engagement of all relevant agencies and the public in search of solutions that are effective in meeting sustainability objectives.’ (CSIRO, 2007). To achieve fair and effective water use, the role of extended education is of prime importance: ‘Without creating awareness among the users and educating the general public on the importance of this precious resource, all conservation measures adopted would be limited. Once they are convinced of its wise use and become water conscious consumers, they will happily put all the suggested water conservation measures into their practice and implement the plans and policies with letters and spirits, offered by the Kingdom.’ (Al-Zahrani and Baig, 2011).

Public engagement therefore is central, and of course there are barriers that would be overcome by a heightening of this awareness. Increased public awareness about and participation in IUWM will empower communities to decide on their level of access to safe water and will they will have a much better idea about how much water they will need for everyday life. It will also influence a sense of responsibility and ability to value water, whether it is fresh, or recycled. In addition, communications with the water authorities will be much more meaningful. The 2009 report The Water Technology Program: Strategic Priorities for Water Technology Program in KSA has provided further important information about the water sector. It cites the King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology (KACST) and The National Policy for Science and Technology which defined eleven programs for the localisation and development of strategic technologies deemed essential for the future development of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA). The eleven programmes were approved by the Council of Ministers in July 2002 and including the Water Technology Program. The technological areas selected were those that best met the criteria and had the greatest potential for developing the scientific and technical capacity of the Kingdom, in addition to meeting urgent water needs:

Water desalination: thermal desalination and hybrid desalination.

Drinking water treatment: membrane treatment, chemical treatment, ionic exchange, disinfection and filtration.

Wastewater treatment: biological treatment, biological membrane treatment, chemo-physical treatment and advanced treatment.

Water resources management: water conservation, water re-use and recycling, groundwater recharge, rain harvest and cloud seeding.

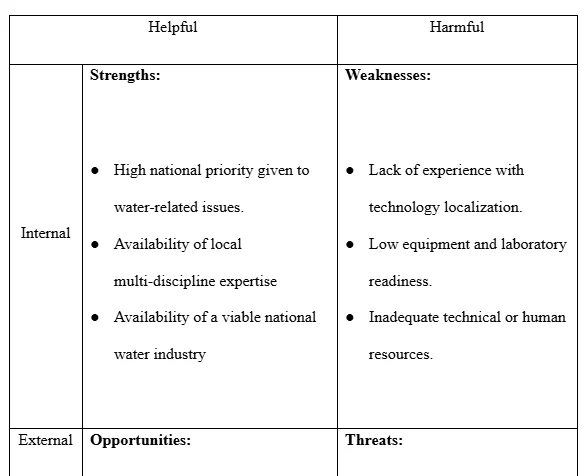

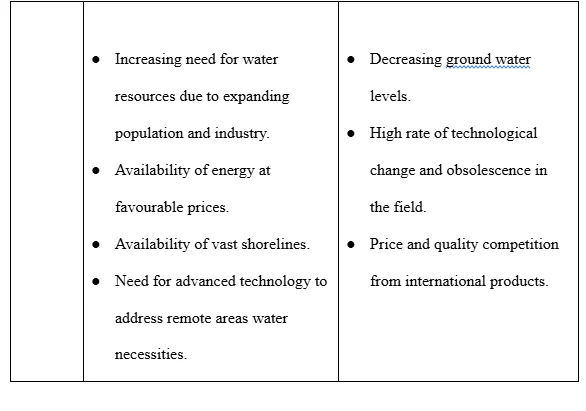

The report also shows the SWOT Analysis (table eight) for the Water Technology Program. This analysis demonstrates strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats or hazards. In a SWOT analysis, strengths and weaknesses are defined as interior to the association whilst opportunities and threats are defined as exterior to the association. The association of this analysis is the water technologies program, including KACST, and other government organisations.

The weaknesses and threats listed by the SWOT Analysis illustrate some of the reasons why the application of IUWM has been piecemeal at best. In order for an effective strategy to be formed, an accurate picture of factors including public awareness must be fully understood. Al-Zahrani and Baig (2011) stated that public awareness and participation was an essential component of IUWM. CSIRO (2007) called for the full integration of all stakeholders. However, until now an effective quantitative and qualitative analysis of data around these stakeholders has never been carried out. Public awareness has never yet been comprehensively measured and without this clear understanding of current awareness, strategies cannot be fully effective. The chapter following will present this data and an analysis of its results. It will be argued that without this knowledge, a fully integrated policy of IUWM cannot be fully implemented.

2.2 Integrated water resources management.

2.2.1: Theoretical approaches to integrated water management.

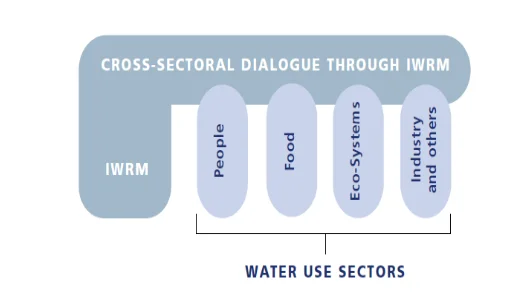

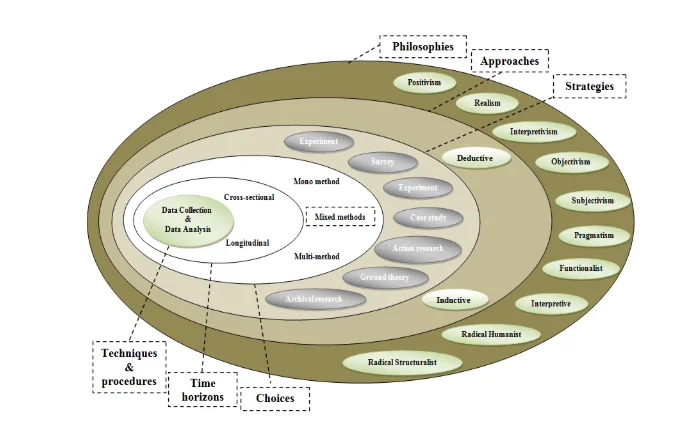

The Global Water Partnership defines integrated water resources management (IWRM) as: A process, which promotes the coordinated development and management of water, land and related resources, in order to maximise the resultant economic and social welfare in an equitable manner without compromising the sustainability of vital ecosystems. (GWP-TAC4, 2000). The key emphasis in this definition is on a ‘coordinated development’. Further clarification was provided in by Grigg (2008), In the study he defined IWRM as ‘a framework for planning, organizing and operating water systems to unify and balance the relevant views and goals of stakeholders’ (Grigg, 2008). This definition gives additional importance to stakeholders’ view and goals. The views and goals will vary depending on the specific cultural and socio-economic context of the environments being investigated. This research aims to identify the views and goals of specific stakeholders within Saudi society and how this influences IUWM. An increased understanding of the role of the consumer begins to be a feature of these paradigms of water management as shown in Figure 5 which represents the movement from sub-sectoral to cross-sectoral water management as described by Grigg (2008); which links the different sections through dialogue, but in practice there would need to be more information about how to systematically organise this dialogue, collect and analyse the relevant data. This research has addressed this issue by identifying how different stakeholders make up the different sectors. A database will then be established to enable a similar cross-sectoral dialogue.

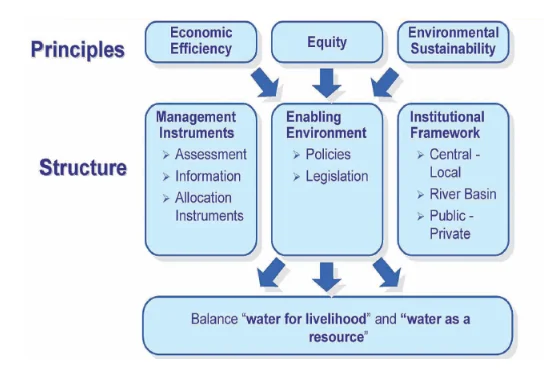

IWRM seeks to manage the water resources in a comprehensive and holistic way, it has to consider the water resources from a number of different perspectives (Savenije and Van der Zaag, 2008; Ait-Kadi, 2014; Gao et al., 2014). Once these various perspectives have been considered, appropriate decisions and arrangements can be made. According to Savenije and Van der Zaag (2008) there are four perspectives of IWRM these are water resources, water users, spatial scales, and temporal scales and patterns. Central to most of the efforts over the last two decades is the concept of IWRM, which has been a nearly universal approach for reforming the water sector (Mostert, 2006; Funke et al., 2007; Hassing et al., 2009; Ait-Kadi, 2014). It is mainly geared towards achieving economically efficient, equitable, and sustainable use of water resources by all stakeholders (Van der Zaag, 2005). Most countries that have adopted the IWRM approach have been confronted with challenges (Gourbesville, 2008). These are mainly in the process of setting up the laws and regulations, implementing institutions, and management instruments and further following up in the process (Gourbesville, 2008). According to the Global Water Partnership, the IWRM model components are summarised into a structure of three pillars that support the three principles and form a base for the balance between the main water uses. This balance can be seen in Figure 6, where the different partners or sectors were divided into management, the institutional or governmental framework and the enabling environment. The enabling environment is the pillar that would have an impact on the behaviour of people, but it is divided into policy and legislation. There is no specific mention of dialogue with the public and it can be argued that policy and legislation alone will be insufficient to change people’s behaviours with respect to water usage.

Van der Zaag (2005) took public and other stakeholders views and stated that integrated water resources management should take into consideration the following four dimensions due to the complex nature of water as a natural resource:

All water resources, taking the entire hydrological cycle into account

The water users, including all sectoral interests and stakeholders

The spatial scale, including the spatial distribution of water resources and the points at which water is being managed, for example individual users, user groups (e.g. user boards), watersheds, catchments, (international) basin; and the institutions that enable this distribution.

The temporal scale; taking into account the temporal variation in availability of and demand for water resources, but also the physical structures are needed to match supply with demand.

Van der Zaag’s arguments also differs in that it takes into account temporal and spatial aspects that account for some of the inconsistencies in water supply into consideration in the evaluation of IUWM. Again more attention has been made to the needs of the public as consumers, but no discussion of the form of dialogue that will be needed with respect to water usage and conservation. These models have been largely theoretical with little indication of how they could be applied practically. Jeffrey and Gearey (2006) argued that IWRM has proved problematic during the transition from the theoretical (its policies and statements) to the practical (its tools and mechanisms) because of two main issues, which are:

Nature of the science which has formed the background of the paradigm;

The theoretical language, which they see as being more appropriate to philosophy or literature rather than engineering; in other words, the philosophical aspects of the language can seem at odds with the science of water distribution.

The International Water Association in cooperation with the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) prepared a report to identify six obstacles to the implementation of IWRM (UNEP, 2002 pp7-9). The report points to the difficulties in applying IWRM practically and argued the lack of reliable data that are essential for successful implementation of IUWM. The six issues include:

The lack of understanding and attention to the positive contribution that innovative workplace approaches can play in achieving IWRM objectives

The potential complexity of the IWRM concept

The need for reference projects

The lack of adequate skills, expertise and awareness

The lack of adequate and reliable data

Gaps in available knowledge and technology

McDonnell (2008) stated a similar problem with applying the theoretical approaches of IWRM. He argued that at present time the possibilities of a truly integrated water resources management are limited. This is not because they lack a conceptual framework, but because these concepts do not represent the complexities and variables that occur in any water management policy or project. The IWRM framework requires new methods. It is important that any proposed paradigm that aims to accomplish the ambitions of IWRM should take into account the work of academic researchers, environmentalists and social scientists in order to create a new approach to the methodology. Thus this research will include the views of a range of participants in order to enable the practical application of IWRM.

Integrated Water Resource Management programmes

There are some examples of IWRM programmes being practiced in different countries. The United Nations World Water Assessment Programme through the UNESCO identified which countries are currently applying IWRM and suggested how these processes can be evaluated. The following examples can illustrate some of the different examples of IWRM (Hassing, 2009). According to the United Nations World Water Assessment Programme, IWRM is a lengthy process. It can take many years to reach the point at which water resources management can finally be managed according to the most important principles of IWRM. In Spain, for example, the fulfilment of the process has taken nearly eighty years. This length of time is an example of one of the practical problems of IWRM (Hassing, 2009). Therefore, this research propose that the process could be facilitated by better dialogue between the different stakeholders. Other countries that are currently applying IWRM are the USA and Mexico. In the USA a conflict occurred as a source watershed in New York became polluted. The WWAP describe how this was eventually resolved at state level, leading to greater economic benefit. Secondly, in Mexico both decision-making and the organisation of tasks were decentralised. This approach, following IWRM principles has led to significant improvements in irrigation at a national level. These examples show how the approach is similar to the three pillared approach Figure 6 in that management, institutions and local legislation worked together to improve the balance between supply and demand for water. IWRM therefore can work at a practical level as well as at a theoretical level. This research will aim to further investigate and resolve potential barriers to the practical application of IWRM (Hassing, 2009).

IWRM: Roadmapping towards the Millennium Development Goals and beyond.

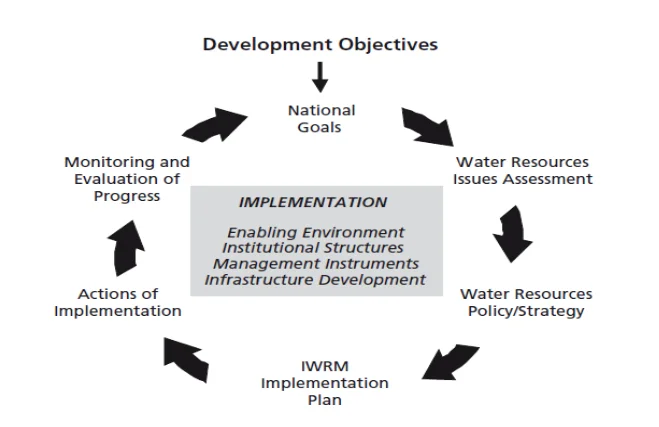

On 16th March 2008, UN-Waterin cooperation with the Global Water Partnership (GWP) announced the Roadmapping for Advancing Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) Processes. This was dependent on the Copenhagen Initiative on Water and Development at the Commission on Sustainable Development (CSD). The roadmap provided another approach to the practical problems of implementing IWRM (Roadmapping for Advancing Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) Processes, 2008). The Copenhagen Initiative is an outcome of the International Conference on Managing Water Resources Towards 2015. It was hosted by the Danish Government in collaboration with UN-Water and the Global Water Partnership and held in Copenhagen on 13 April 2007 (Hassing, 2009). The Roadmapping Initiative aimed to support countries in their efforts to improve water management through an IWRM approach, and also to support the achievement of the seventh Millennium Development Goals (MDG7) which included adaptation to climate change. The initiative showed how changes in water can be organised into stages to support the achievement of the national goals through roadmaps. Figure 7 demonstrates some of these stages, showing both planning and implementation.

How effectively does IWRM map on to sustainable management?

The theories of IWRM will now be compared to methods of sustainable water resources management. Over time they have become global networks with widespread interconnections. These include Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), Intergovernmental Organisations (IGOs), government departments, private foundations and think tanks, private companies, universities based on academic research and consultants. These global networks are immediately accessible. A single website (e.g. http://www.righttowater.org.uk) has links to other websites operated by groups such as the World Water Council, the World Water Forum, the Global Water Partnership, the International Water Management Institute, the International Rivers Network, Water Aid UK, IUCN, and several UN agencies (for example World Bank, UNESCO, WHO). Each of these websites lead to many others and to a series of policy documents and scientific papers dedicated to the sustainable water resources management (SWRM) (Swatuk, 2005). At the heart of this multiplicity of agencies however, is the conception of integrated water resources management (IWRM). WRM is defined as: ‘Equitable access and sustainable use of water resources for all stakeholders at regional catchment and overseas, whilst sustaining the features and integrity of water resources at the catchment range inside approved restrictions’ (Pollard, 2002). Loucks (2000, p.3), demonstrated that the sustainable management of water resources is a concept that emphasises the need to take account of the long term future as well as present needs. It is also a system of water resource management that is administered to meet the changing demands that can impact upon them in the future, without any degradation of the system. Such a system can be described as ‘sustainable’ according to the definition of sustainability as offered by the American Society for Civil Engineers): ‘Sustainable water resource systems are those designed and managed to fully contribute to the objectives of society, now and in the future, while maintaining their ecological, environmental, and hydrological integrity’ (ASCE, 1998). IWRM principles therefore can be found in sustainable systems. This can go some way to answer the claims that IWRM is too theoretical. For example, Jeffrey and Gearey (2006) argued that the goal of achieving ‘sustainable’ water resources management is best achieved through the Implementation of the IWRM strategies, which both encapsulate and apply all of the four Dublin Principles, which are:

Fresh water is a finite and vulnerable resource, essential to sustain life, development and the environment.

Water development and management should be based on a participatory approach, involving users, planners and policy-makers at all levels.

Women play a central part in the provision, management and safeguarding of water.

Water has an economic value in all its competing uses and should be recognised as an economic good.

Points two and three are particularly relevant to IWRM strategies, where public participation is essential. This research will investigate and expand on these important points and add to the current knowledge by investigating possibilities of public awareness and participation.

Seven factors towards successful IWRM implementations

Having established that IWRM is suitable for practical application, Rahaman and Varis (2005) highlighted seven key approaches which should be adopted by water professionals to enable its implementation. These points are as follows:

Privatization,

Water as an economic good,

Transboundary river basin management,

Restoration and ecology,

Fisheries and aquaculture,

The need to learn from past IWRM experiences and

The spiritual and cultural aspects of water.

In addition to being pragmatic, Rahaman and Varis’ points also tailor the IWRM to meet different contexts during its implementation. Also, the World Bank is in agreement with this need for practicality, as this definition shows: ‘The main management challenge is not a vision of integrated water resources Management but a “pragmatic but principled” approach that respects principles of efficiency, equity and sustainability’ (World Bank, 2004). The literature shows examples of how IWRM needs this range of integration through all levels of society. Allan and Rieu-Clark (2010) point out the need for governmental support, pointing out that accountability, participation and transparency appear to be the key elements of good governance of IWRM, although it is clear that these are not by themselves sufficient to support IWRM unless the governance regime addresses the access points between them (Allan and Rieu-Clark, 2010). When IWRM is practiced in a way that includes all these different stakeholders, it has the potential to become what the World Water Council are aiming for in their discussion of water policy paradigms. They demonstrate that the IWRM approach employs participation; negotiation and dialogue in order to arrive at solutions that are beneficial to all parties. Overall, there is a general opinion that IWRM has been proved as a flexible approach that can adapt water resources management into diverse cultural, social, political, economic or environmental contexts. However, it will be necessary to propose a paradigm that will take into account all these theoretical, practical and participatory needs that have been discussed in the literature. This research explores the most effective methods to achieve this.

Marketing

A marketing approach is significant to water management as household consumers mainly in urban areas regularly obtain water from many alternative sources and providers. At some level, water utilities are in competition with alternative water obtained from sources that are untreated. The alternative water supplies often substitute or supplement water that is provided directly by utility and are accessed through informal physical and human networks. Thus, it is clear that there is need to have an efficient and customer-focused marketing strategy in water management. As described by Hutt and Speh (2005) marketing management can be taken to imply the marketing mix concept. Marketing mix can be defined as a conceptual framework that highlights the critical decisions made by marketing managers in configuring what they offer to the market to suit the needs of the customer (Hutt & Speh, 2005). Consumers have a continuous reaction towards their private desires as well as their external environment which serve as drivers of behaviour. According to Ivy (2008), there are 7Ps of the marketing mix. First, there is the product which is expected to provide value to the customers but may be intangible at the same time. Second, marketing mix involves pricing whereby it must entail profit and competitive as well. Third, there is the place where the consumers can purchase the product and the means by which the product reaches out to the area. Marketing mix also involves promotion which comprises of the many ways that communication to customers can be made regarding what is being offered to the market. Among the 7Ps is the people, which refers to employees, customers as well as the management and all stakeholders. Further, there is the process which relates to the processes and methods of providing a given service. Thus, it is fundamental to have an understanding of whether the product is of benefit to consumers, if it is made available on time and if customers are well informed about it. Additionally, there is the physical aspect which refers to the experience of using the service or product. However, after the completion of the initial piloting work, there are reasons why water management needs to be reasonably comprehensive and strategic. One of these grounds is that there is the need for utilities to feel confident that if new services and opinions are to be offered, they can be provided on a basis that is reliable and sustainable. Also, equity and precedence should be taken into consideration implying that fair and rational targeting or new investments prioritising is required (Ivy, 2008). Successful water management, like any other business, seeks to meet customer satisfaction, increase market territory and hence maximise revenues. As such, it is vital to take care of the customers’ attitude in order to achieve satisfaction. Constantinides (2006) states that marketing also involves investigating consumer behaviour in relation to a given product. This is because identification of the customer behaviour may play a significant role in satisfying the customers` requirements. According to Biswas (2004), consultation and collaboration with different stakeholders are critical to water management. Essentially, every individual plays a role in the fulfilment of the use and protection as well as sustainable water management. Some of the main benefits of consultations and collaborations as highlighted by Biswas (2004) include strong relationships in terms of respect, trust, improved negotiation and information sharing among participants and stakeholders. Also, collaboration helps to increase the chances of success in the plan implementation due to the collective involvement of all stakeholders.

Integrated Urban Water Management (IUWM)

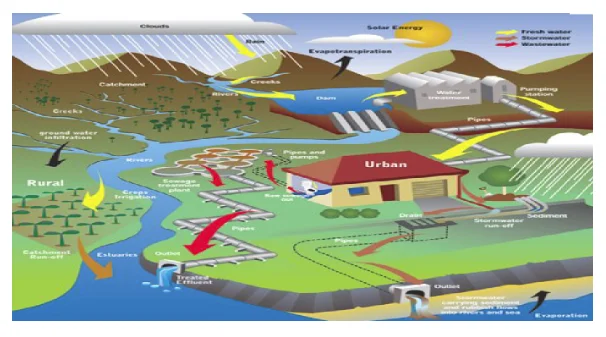

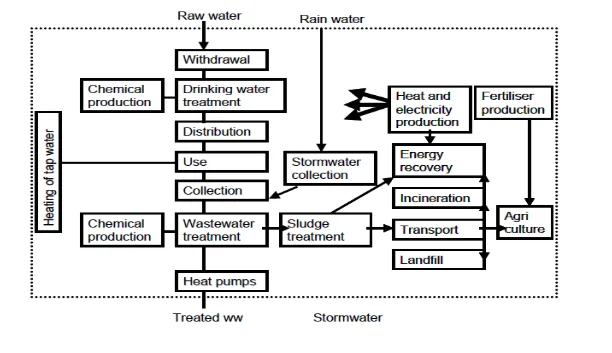

The critical review literature in this section discussed different ways in which Integrated Water Resources Management can have a practical, multi-agency application in addition to a theoretical aspect. This research will also explore ways to successfully integrate the different practical and theoretical approaches into a new proposed paradigm. Firstly, however, moving on from IWRM, literature around integrated urban water management will be reviewed. The value of these models to this research will be also assessed. Figure 8 illustrates the Urban Water Cycle. This water cycle is centred on practical human uses which include; storage facilities, irrigation, domestic and industrial use, treatment and return to waterways. It is a reflection of how the Water Cycle of evaporation and rainfall, cited at the very beginning

2.2.2: The need for Integrated Urban Water Management

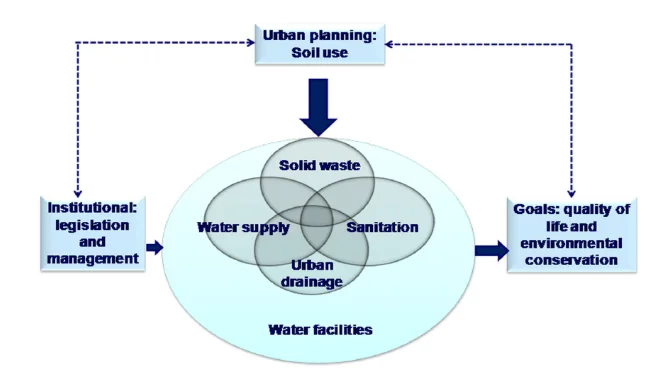

In the course of this literature review, different ways of looking at integrated water resources management were studied. It was agreed that although IWRM can be applied practically, an effective paradigm was lacking. Now, the possibility of including a specifically urban aspect will be assessed. Bahri (2011) argues that the idea behind Integrated Urban Water Management (IUWM) is to address the entire urban water system as part of a coherent framework. Figure 9 describes some of the interrelated activities that IUWM brings together and will illustrate how this paradigm differs from Figures 5 and 6 above. Similar to the urban water cycle, Bahri’s model takes into account human actions and places them at the centre of the diagram.

In addition to taking human actions into account, Bahri (2011) also states that the implementation of IUWM needs well managed institutions, with a range of public and private stakeholders who are in turn supported by a policy framework and appropriate legislation. The need for effective partnerships is becoming clearer. A range of partnerships will also necessitate a range of activities. The United Nations Environment Programme (International Environmental Technology Centre) produced a brochure about IUWM, explaining it to be the practice of managing freshwater, wastewater, and storm water in addition to making links within the resource management structure and using an urban area as the unit of management. Activities under the IUWM umbrella are extensive and include the following:

Improve water supply and consumption efficiency

Ensure adequate water quality for drinking water as well as wastewater treatment through the use of Environmentally Sound Technologies (ESTs) and preventive management practices.

Improve the economic efficiency of services to sustain operations and investments for water, wastewater, and storm water management.

Utilise alternative water sources, including rainwater, and reclaimed and treated water.

Engage communities to reflect their needs and knowledge for water management.

Establish and implement policies and strategies to facilitate the above activities.

Support capacity development of personnel and institutions that are engaged in IUWM. (UNEP, 2007)

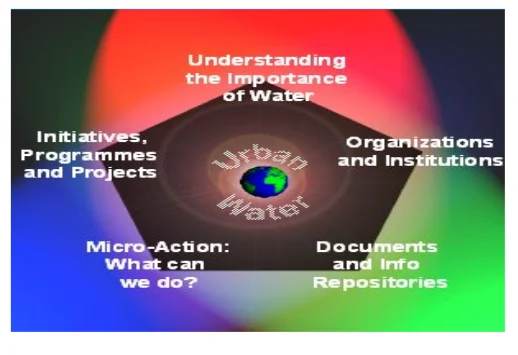

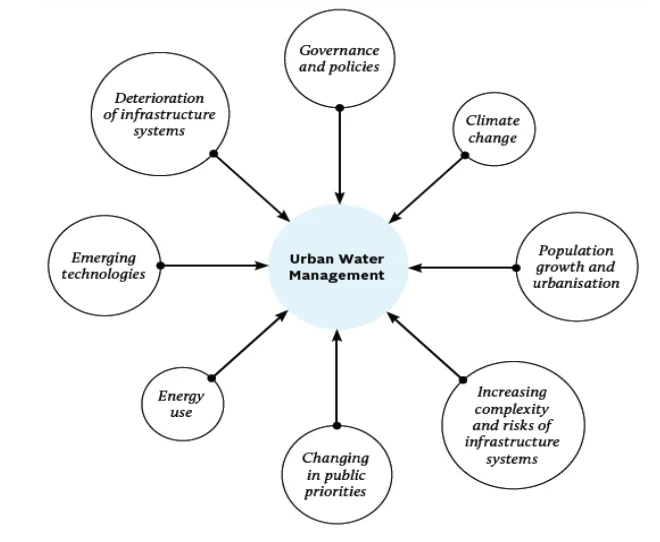

Figure 10 groups different activities into five dimensions of the urban water system, which are seen as playing vital roles in providing urban water.

Significantly, one of the five points of figure six is ‘micro-action: what can we do?’ This micro-action will operate at the level of human actions, essential to integrated urban water management. The question however can only be answered by a range of appropriate data for the different urban locations, similar to that which will be undertaken by this thesis. The research will in turn provide the database that can form the basis for these micro-actions. These micro-actions or local actions also play a part in what can be called the twin dilemmas for cities in their application of IUWM. As in Figure 9 they centre around human needs and human actions. Factors that create an imbalance between sanitation and the provision of clean water are shown in Figure 11 below.

Mays (2009) also agrees that there is a need for a specifically urban aspect to integrated water management in Urban Water management: Arid and Semi-arid (ASA) Regions. They describe how the engagement of a range of stakeholders can go some way to resolve the dilemma of sanitation and water provision, through including a specifically urban aspect to water management. To paraphrase Mays, there is a strong opinion that IUWRM could be considered as an essential component of IWRM within the problematic context of urban areas. Stakeholder involvement for IUWRM should involves those responsible for water supply and sanitation services, storm water and solid waste management, regulating authorities, householders, industrialists, labourers, environmentalists, and recreation groups. Although local authorities are able to initiate and oversee IWRM/IUWRM programmes, planning and implementation should be led by a combination of top-down regulatory responsibility and bottom-up user needs. However, top-heavy governmental approaches are to be discouraged due to bureaucracy and because it discourages dialogue with water users (Mays, 2009). Because of the nature of the different stakeholders at this urban level, an effective dialogue must be set up so that water users develop a sense of responsibility for the provision of their water. This will be addressed in the course of this research as the need for public awareness and participation is debated and analysed.

What are the differences between IWRM and IUWRM/IUWM?

To summarise this section of the literature review, overall, the only difference between IWRM and IUWRM/IUWM is that the IWRM process is an overarching process that combines all relevant water issues and water management strategies, for both rural and urban areas including paradigms, programmes and plans into a pool of effective water governance. IUWRM/IUWM, on the other hand, is a specific sub-approach of IWRM approaches concerning water issues in urban areas. For the purposes of this research project, the social inclusion aspects that play a major role in the implementation of IUWM will be taken into account in the investigation of the public engagement in urban water management. It will now be necessary to look in more detail at these stakeholders.

2.2.3: Stakeholders and Public Participation

Castelletti and Soncini-Sessa (2006) defined stakeholders as those people, institutions and organisations that self-consciously react to decisions made on their behalf, while the decision maker is the individual that is responsible for making and implementing those decisions. A procedure that aims to make decisions on behalf of stakeholders is called informative participation. Before a decision is made on their behalf, they should become actively involved in in the process, as if they were decision makers themselves (Castelletti and Soncini-Sessa 2006). The important point is that the stakeholders must feel that they have some ownership over the decision making process. It goes some way to answering Mays’ concerns that governmental legislation alone will not be enough to promote IUWRM (Mays, 2009). This notion of dialogue and ownership will presently form the basis of a fundamental part of this research. Castelletti and Soncini-Sessa further discuss the process of public participation confirming that all related issues should be voiced in order to achieve informed and creative decision-making. Where new views are presented, new approaches can begin and alternative decisions can be considered. Secondly, public participation enables social learning, where stakeholders and decision makers can interactively to manage and solve conflicting views and interests. Similarly, Rahaman and Varis (2008) have revealed that the key issue in achieving efficient and effective water resources management is to initiate a management system where decision makers collaborate with the scientific community, water users, local communities and other stakeholders during a coordinated procedure. This challenge of working towards the active involvement of stakeholders in the management and development of water resources should be achieved via consultation, coordination and collaboration with social groups, private enterprises, farmers, women and other water users. These writers agree that there is a particular need for public participation in efficient and effective water resources management. Rahaman & Varis also discussed that in the case of urban water management, there should be recommendations to encourage public participation with local water organisations. This should help to optimise water use, protect water quality in urban areas and manage sanitation and water supply systems. In addition, Bell (2001) had stated that community involvement in IWRM or in other environmental issues is centred on three basic reasons:

The emergence of a participatory approach demonstrates the importance of gaining the consent of local communities in taking part in public decision-making processes, especially on issues that directly affect their welfare. In this context, the participation of the local community could provide an important database of experience and ideas that could lead to practical, relevant, achievable and acceptable solutions to water related problems.

The need to use indigenous knowledge as well as opinion is vital to environmental protection, including proper water resource use and management.

The need to build public trust: Lack of public trust might lead to protest and antagonism between water resource users and other stakeholders due to varying interests and demands. (Bell, 2001)

In support of this, Dungumaro and Madulu (2002) state that:

The involvement of local communities in water projects does not only ensure democracy, but also ensures acceptability, support, and sustainability of the respective projects. The concept of bottom-up planning necessitates participatory approaches and involvement of local communities and other stakeholders from the grassroots level. This approach is the best option to IWRM because it ensures public trust, awareness and interest. (Dungumaro and Madulu,2002) J.B. Bekbolotov, writing about water management in the Kyrgyz Republic has declared a similar definition in that the main objectives of public participation in integrated water resources management are:

to ensure the use of the knowledge and experience of the public and other stakeholders in planning and management processes;

guarantee identification of decision quality and adaptation to specific conditions;

provide adequate planning and identification implementing decisions in practice;

ensure consideration of public needs and priorities in the making of managerial decisions. (Bekbolotov, 2002)

Also Bekbolotov clarified the basic principles of the public participation in integrated water resource management as:

active involvement of all the stakeholders and the general public, directly or indirectly;

the process should be open and transparent, be conducted fairly and impartially, based on exchange of information, data and knowledge, using all appropriate information media; it is necessary to foresee certain conflicts and solve them;

suitable mechanisms should be adapted to local conditions, to the problems and needs of all participants, focusing attention on reaching a consensus;

participants should adopt a long-term vision on an acceptable condition of studied water body, watercourse or shore, recognising the differences in their interests, working together and learning from each other;

this participation should not only consist in solving problems, it is necessary to provide opportunities for economic welfare and nature conservation, compatible with broader acceptable development objectives. (Bekbolotov, 2002)

There is a strong degree of consensus from these writers from different parts of the world. They have all demonstrated the need for a broad approach that will integrate both top down and bottom up planning through this attention to different stakeholders, particularly in an urban environment. Where this research will expand on these findings, is in the creation of a database that will encompass local knowledge and needs in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, therefore enabling effective planning from decision makers within institutions. These decision makers will be discussed in the section following.

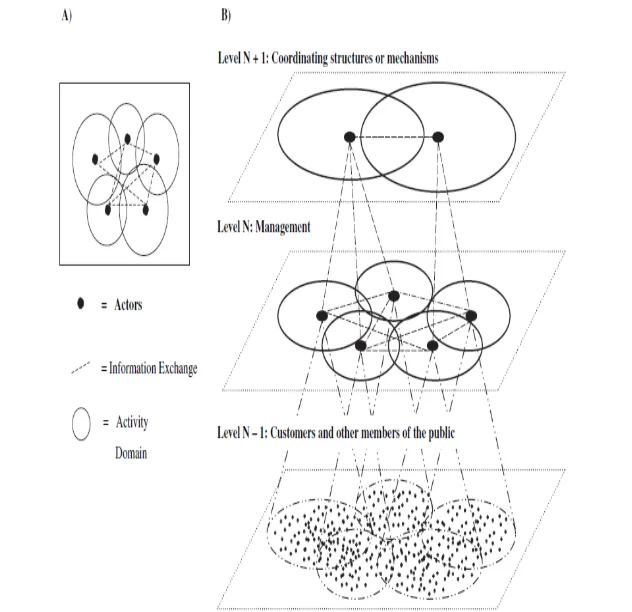

2.2.4: Institutional Arrangements

Institutions are ‘the sets of rules or conventions that govern the process of decision making, the people that make and execute these decisions, and the edifices created to carry out the results’ (Gunderson et al., 1995). Cowie and Borrett (2005) have discussed that urban water management could be improved through a greater integration of ‘actors’ (or agents) and management institutions building a more interactive IUWM hierarchy as shown in Figure 12 below. This is a reciprocal and by implication productive dialogue between systems, managers and consumers, bringing about a transformation the familiar model of top-down management, where communication is necessarily central. The notion of a productive information exchange is also key to their conceptual model in figure 12 below.

In the figure above, it can be seen that a manager can be differentiated on the basis of the resource streams of key concern. A manager may focus entirely on the supply of drinking water while another may solely be concerned with the management of storm-water and the receiving stream`s assimilative capacity. Thus, each manager has their own activity domain which is determined by the resource streams of concern. The activity domain is also determined by the manager`s decision making authority in relation to the resource streams as well as the inter-relationships between the resource streams. Overlapping is possible for the activity domains and there is a variation in their sizes. Further, as depicted in the figure, interactions between various resource managers across the activity domain is facilitated by both formal and informal communication channels and cooperative arrangements. Of great importance is the information exchange that is depicted in the figure and which is considered as a key element of the conceptual model of IUWM. Information exchange plays a significant role in the development of positive public participation and awareness which ultimately enhances Integrated Urban Water Management.

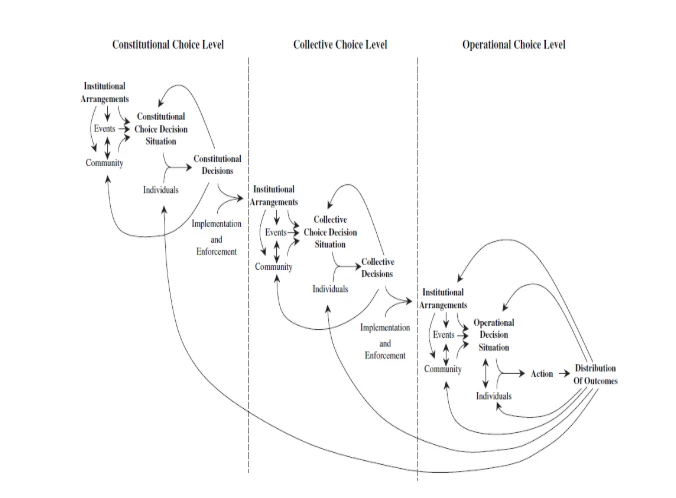

As illustrated in figure 13, in resource management and use, three distinct action levels can be identified namely collective, operational and constitutional. At the operational level, individual decisions affecting the physical world are made and are based on institutional arrangements as well as decisions made at the level of collective choice. However, constitutional choice decisions are said to limit those made at the collective choice level (Cowie & Borrett, 2005). Though actions made at lower levels are bounded by those at higher levels, operational level actions are responsible for the direct effect on resources as well as the resource-use outcome distribution. Assessment and monitoring of information serves as a platform for providing feedback at the operational level regarding outcome distribution and the information can also provide feedback to the constitutional and collective choice levels (Cowie & Borrett, 2005). Therefore, assessment and monitoring provide feedback on the status of resource for operational actors` use when making production and appropriation decisions. The feedback provided in the levels of action is also promotes and encourages public and stakeholders` participation as well as their awareness which consequently enhances Integrates Urban Water Management. It can be seen through these diagrams that institutional organisations within IUWRM systems are complex, but rely on productive dialogue. However, Cowie and Borrett’s models are theoretical and do not suggest the means by which the groups of stakeholders can interact. A procedure that may go some way towards a practical integration of these different stakeholders will be discussed in the section following.

Participatory and Integrated Planning Procedure (PIP procedure)

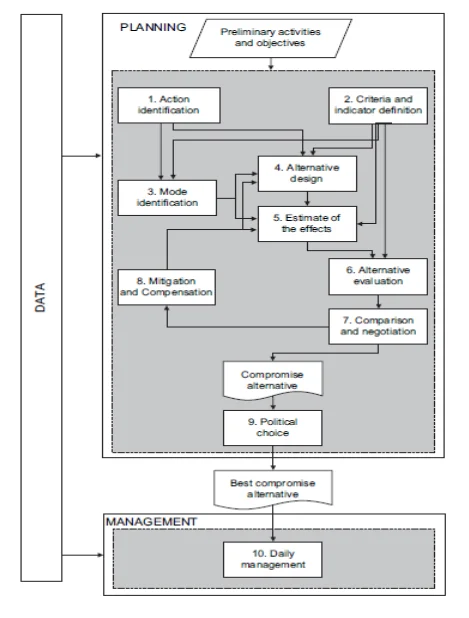

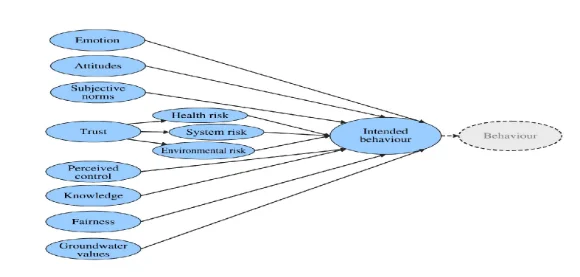

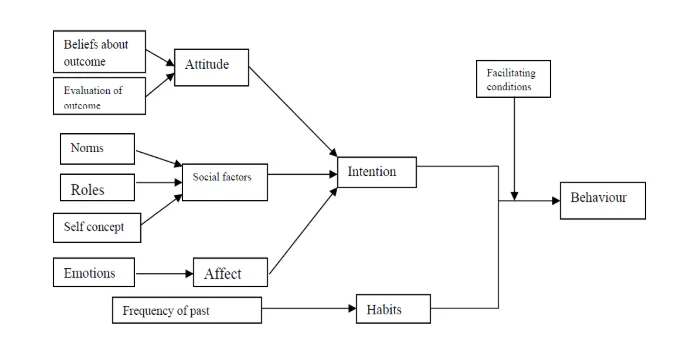

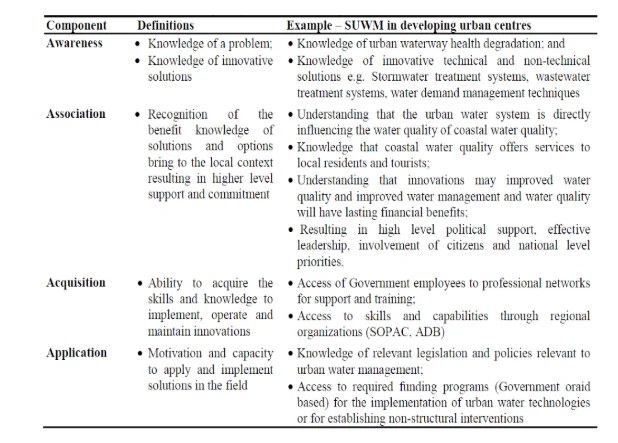

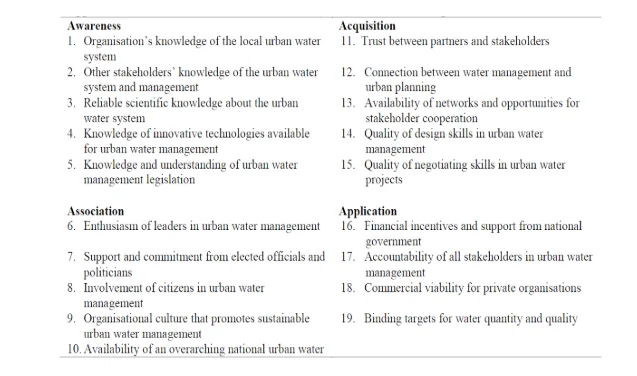

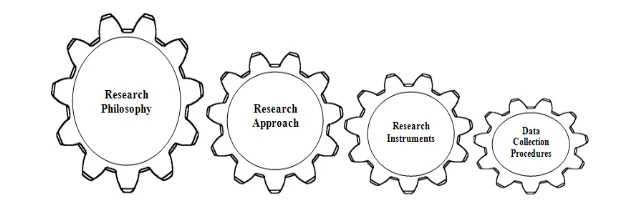

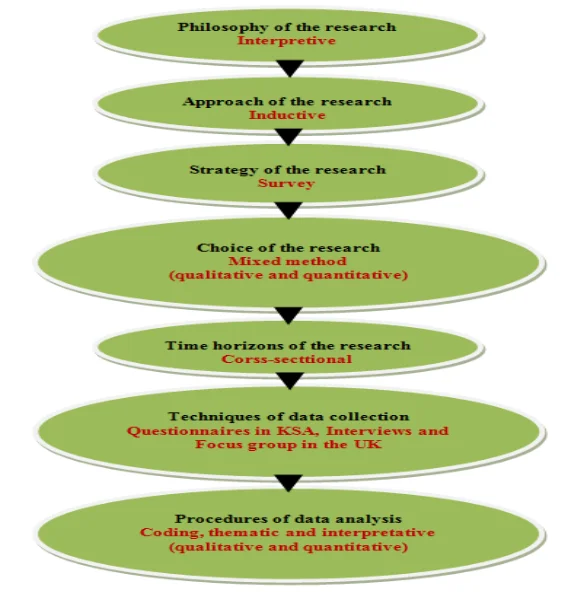

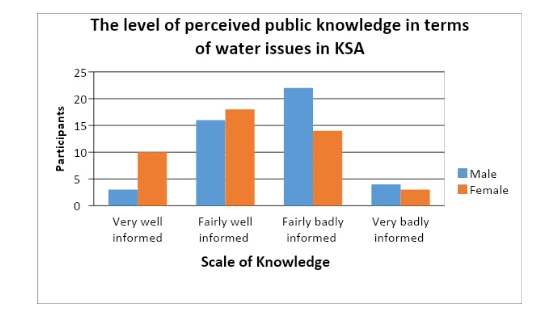

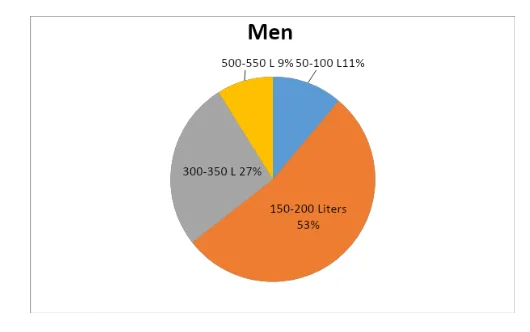

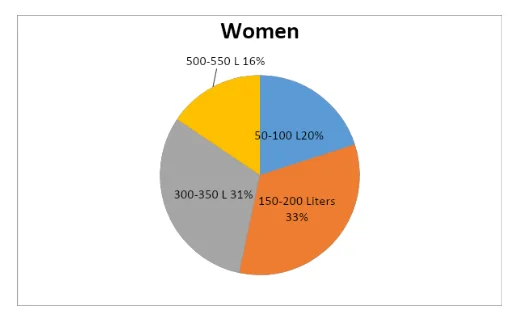

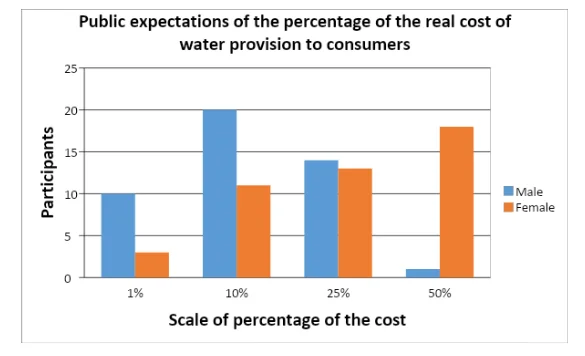

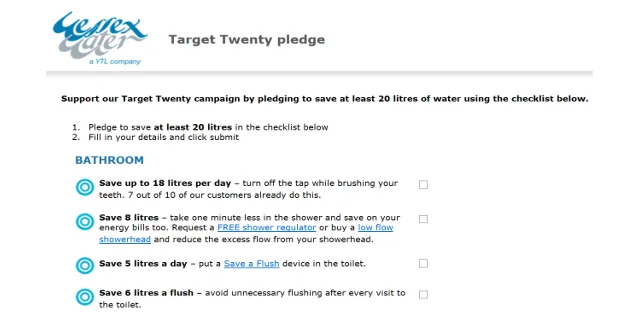

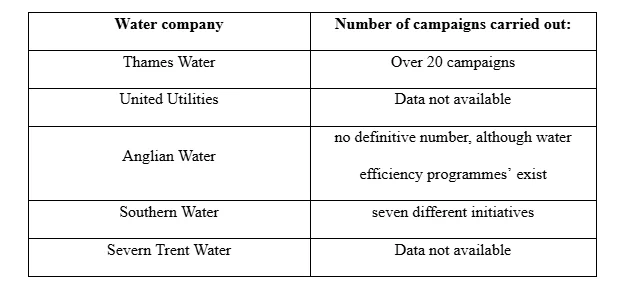

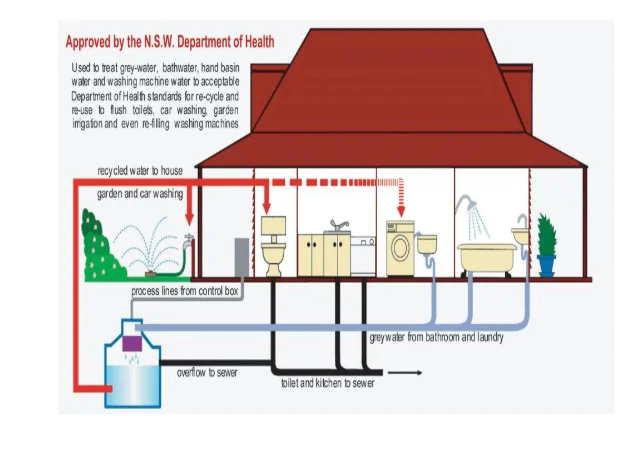

One of the more suitable approaches to achieve the effective governance of (urban) water resources management is to follow the Participatory and Integrated Planning Procedure (PIP procedure). The PIP procedure is a methodology that consists of nine phases. They start by identifying the objectives of the planned actions and finish with a negotiation process between the stakeholders. This in turn will generate a set of alternatives or compromises that can be submitted to the decision makers as a final political decision (Castelletti, and Soncini-Sessa 2006). They explain that PIP is a recursive procedure as opposed to an algorithm, which indicates that people are continuously involved during the process. Decisions therefore must be taken at every stage on the basis of both subjective judgements and negotiations. Also PIP is a very versatile process, successfully used by many disciplines (e.g. Ecology, Hydrology, Sociology, Decision-making, Theory, and System Analysis). The following scheme, Figure 14, depicts the different steps of the PIP procedure: