Independent and Supplementary Prescribing For Nurses and Midwives

Critical reflective evaluation

Demonstrate the ability, using a range of assessment and consultation skills, to understand and use a detailed and thorough client history/interview (which includes the past and current medication to inform diagnosis and promote concordance.

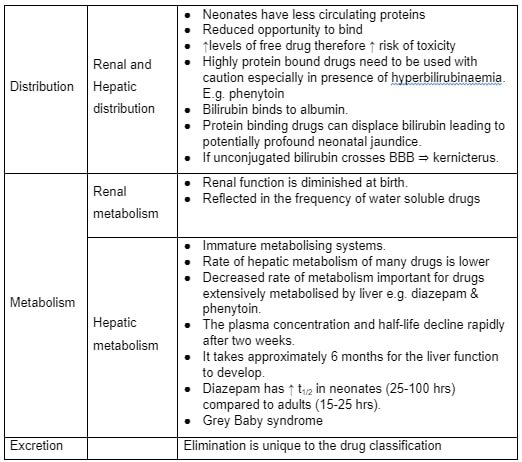

Several consultation models were employed in prescribing practice but widely applied one in acute care was Calgary-Cambridge model. It complemented practitioner’s traditional holistic assessment approach to demonstrate proficiency in consultation skills (Moulton 2007). The Practitioner undertook full assessments, history-taking from neonates’ parents and accessed electronic data based on Calgary-Cambridge model with Patient-centred approach. Pre-established rapport was used to promote concordance and adherence with professional accountability and responsibility for decision-making (NMC 2006). For those seeking guidance in this area, healthcare dissertation help can provide insights into how these models can be effectively applied in practice. Unique to this population, neonates required more detailed history regarding past and present maternal as well as neonatal medications, and, hence, various consultation models were used. In neonates’, holistic assessment presented challenges including the need for comprehensive history collection, electronic patient data, and medical notes comprising neonatal and maternal history including polypharmacy (Placencia, 2011). It was particularly challenging due to missed antenatal care in certain cases namely safeguarding and concealed pregnancy scenarios, and patients transferred from other hospitals. Additionally, it was a challenging experience because parents had language barriers (Abbe, 2006). This was managed with the help of interpretation services for eliciting all relevant information to inform diagnosis, differential diagnoses and promote concordance. For example, there was a mother from abroad who delivered her baby prematurely while visiting the UK. She could not speak English and hence interpretation service was helpful in obtaining complete history (RPS 2016). It is noteworthy that, interpretation services are scarcely available when necessary in practical situations. Successful completion of Assessment of the New-born Module (Appendix 13) is an evidence to support practitioner’s ability to perform a full assessment and history taking. The facilitation of consultation models and shared decision-making (SDM) had been a challenge due to parental preferences, but adequate explanation and knowledge-sharing facilitated agreement between parents and Practitioner whilst respecting parental beliefs and wishes (DOH 2004). The above was possible by observing senior medical prescribers, review of evidence and practice of competencies by using different consultation models (WHO 2015 & Silvermann 2004). During clinical assessments and review to make informed diagnosis (DOH 2006), Calgary-Cambridge model was the most useful model in Practitioner’s experience. Its ease of use and relevance was helpful despite the complexity of shared decision-making in a stressful environment (NICU) which presented unique barriers (Yee and Ross 2007). Each family required varying degree of participation in SDM (Table 1) comprising mutual listening, discussion of information and concerns (Kavanough et al., 2005). Robust communication was ensured in each neonate’s care including special attention to emotional aspects of interaction such as listening to parents and caring attitude during consultation (NICE 2009). Patient-centred approach and adequate information sharing promoted concordance and adherence (DoH 2016). While the above model was highly suitable, Disease-Illness model, hospital clerking model, Byrne & Long model, Stott & Davis and Roger neighbour model were less useful. However, Pendleton model was helpful to Practitioner in scenarios requiring review of neonates and follow-up care. In spite of reasonable adaptation in consultation models (NICE 2009), parents often perceived consent as ‘’assent’’ to the already made decisions (NICE 2015). Prenatal consultation framework, decision aids and educational tools promoted concordance in a challenging environment despite the ‘’paternalistic’’ reputation (Griswold and Fanaroff 2010, Yee and Suave 2007). In prescribing practice, comprehensive history collection informed diagnosis and differential diagnoses (Young et al. 2009) and dictated times for monitoring trough levels of Gentamicin and Vancomycin. According to the scientific evidence, aminoglycosides are increasingly prescribed in case of neonates patients, but the matter of concern is that there is a lack of accurate guidance on the prescription and administration of the medication in terms of monitoring of the dosage and concentrations due to absence of proper scientific evidences (Dersch-Mills, 2012). Gentamicin is one of the most commonly prescribed drugs among the patients within the Neonatal Intensive care unit (NICU) and therefore, it is often administered within the 24 hours after the birth along with the beta lactam group of antibiotics to prevent the onset of neonatal sepsis. Moreover, it is also observed as per clinical reports that Extended-Interval Dosing (EID) of aminoglycosides is associated with wide range of benefits. It has been also observed that routine dosage of medication gentamicin diminishes the aspect of preparation of pharmacy along with the administering time of the nurses which eventually causes lesser manoeuvrings of the intravenous line and diminished risk of the infection associated with the line (Dersch-Mills, 2012). Use of common diagnostic aids were critical to prescribing safely (Royal Pharmaceutical Society [RPS] 2019, Department of Health [DoH] 2016 and While 2002). Although, assessment, history-taking and diagnostic skills were highlighted as key areas for improvement for non-medical prescribers (Latter et al. 2011), the practitioner is on track with due emphasis in relevant modules including diagnostic reasoning in ANNP training and Prescribing portfolio (NPC 2016). From the before mentioned sentence, and also from the scientific evidence it is clear that the practice of prescribing is considered to be a intricate procedure associated with varied risks and there are also scope of many medical blunders or drug errors which are influenced by a lot of factors (Swinglehurst, 2011). This was demonstrated in the service-user feedback (Appendices 10 & 11). The learning objective achievement is further demonstrated by completion of medicine management training (Certificates-Appendix 14). The practitioner demonstrated detailed history-taking, physical examination, review of test results and participation in clinical management plan (CMP) (Appendix 8) with conducive environment and communication skills to promote concordance (Lloyd 2007). In this regard, it must be mentioned that in medical practice, the medication prescribed must be consumed by the patients; otherwise it represents a gigantic loss with regard to the medication and the costly time of medical practice. Therefore, compliance and adherence are considered to be the fundamental pillars of the augmentation of concordance. However in this regard, it should be also mentioned that not all the patients or their carers remain ready or are found suitable for the purpose of shared decision approach, few even prefers the decision should be taken by the clinical specialist but maximum number opts for the partnership approach (Swinglehurst, 2011; Cushing, 2007). Although, it is agreed that consultation models render structure, it is acknowledged that these General practice-derived models are not always appropriate for application in acute care (NICU) setting, yet, Calgary- Cambridge model was more suitable (Kaufman 2008). DMP time permitted observation and emulation of consultation styles facilitating Practitioner’s development during which Calgary- Cambridge model was often applied demonstrating its key stages. Stages-Figure 1 include session initiation, information gathering, planning with explanation and closure of session, although safety netting, fourth checkpoint stuck with practitioner’s style optimising parents’ empowerment and practitioner protection (Prescribing Video assessment demonstrates it). Additional advice and ongoing professional support was necessary (RPS 2019) and prescribing medicine being a clinical requirement within the registrant's role, communicating within the team helped minimise errors and justify decisions (NMC 2018). Thus, an ideal model for consultation, most suitable for NICU setting evolved as evidenced in Prescribing video Viva and CMP (Appendix 8) during which RPS standards and NMC code were applied (NMC 2009). The learning objective was further demonstrated from personal learning (Personal learning log- Appendix 7), interim and final DMP reports (Appendices 1&2) and a pass in Prescribing video assessment (Appendix 8).

Demonstrate an extensive knowledge of drug actions and ability to critically apply this knowledge with initiative, and originality, to the development of individual clinical/medicines management plans.

Pharmacological knowledge application was crucial to good prescribing practice since neonates have additional risks of (un)diagnosed genetics impacting drug handling (Baxter 2012 p7) which is essential in neonates (National prescribing centre [NPC] 2003). Practitioner’s knowledge is up-to-date (DMP log & Personal log) and demonstrated prescribing proficiency to meet public expectations and safety (NPC 2001 & 2012). Neonates have unique distribution of intracellular and extracellular fluids requiring broader thinking and critical analysis of intended and unintended fluid shifts due to changing size of kidney and liver and their functions whilst navigating through disease states (World Health Organization [WHO] 2007). For example, in a NICU scenario, although pulmonary oedema in a neonate would benefit from a diuretic Furosemide (Oh 2015), a nephrotoxic drug prescription could be avoided by appropriate fluids’ management plans and optimized electrolyte levels. Hence, a potassium-sparing diuretic, Spironolactone was prescribed. Moreover, as per scientific reports, respiratory distress is considered to be one of the most frequent problems that many of the neonates encounter within the initial days of their life. As per the updated reports of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) nearly 10% of the neonates suffer from the breathing problem following birth, whereas 1% of the neonates demands wide-ranging resuscitation. Therefore it is considered to be the foremost reason of mortality among the neonates. The present system of the non medical practice includes the training of the healthcare professionals along with the alteration in the range, formulation and strength of the drugs available. Moreover, the nurses are allowed to prescribe according to the Nurse Prescriber’s Formulary along with all the licensed medications, the usual sales list medication, and the choice only drugs. More enhanced drugs can be prescribed by the nurses but those are allowed only in the presence of a framework which is being monitored also being referred to as “dependent prescribing”. Moreover to practice up to date practicing, it is required that the nurses should occasionally attends conferences and should subscribe and go through professional journals or scientific communications to keep themselves knowledgeable in the future (Benterud, 2009).

Looking for further insights on Reflective Practice in Nursing? Click here.

Neonates have a large body surface area (BSA) disproportionate to body weight with immature skin. Hence, fluids can be lost through transdermal losses despite humidified settings, which are difficult to account for (RPS 2014). Born premature with smaller kidneys and liver coupled with immature organ functions including poor immune function did not simplify prescribing practice (World Health Organization [WHO] 2007). Hence, it requires regular blood tests to ascertain electrolyte values and drug trough levels. Immature renal function led to challenging situations requiring amended doses and regimen for prescribing drugs, and some are not even licenced to be used in neonates (NMC 2009). The morbid state of organs and unpredictability of neonatal response to drugs posed increased risks for drug errors and warranted frequent monitoring and almost daily or twice daily reviews or more (Bordage 1994). Additionally, working weights varied frequently requiring repeated prescriptions based on progressive working weight with 80-85% fluid composition. Owing to increased error potential, drug administration was double-checked by two nurses, the question remained as why not double-sign neonatal drugs’ prescriptions for enhanced safety since neonates are too vulnerable to drugs’ toxic effects. Neonates experienced oedema including pulmonary oedema especially during perioperative period requiring diuretics usually Furosemide to reverse abnormal fluid shifts, although dose depended on renal function and electrolyte levels. Impaired renal function required alternative diuretics like Spironolactone prescription to prevent nephrotoxic effects of Furosemide. In the process of removing excess fluids, potassium-sparing diuretic, Spironolactone was useful and required monitoring of fluid and electrolyte balances alongside renal function. Conditions such as PDA made it harder (NICE 2016) and prescription of Ibuprofen or Paracetamol was a debate of its own with suboptimal intestinal maturity and circulatory challenges in neonates (NICE 2016). Un well neonates (both term and pre term) were often fluid restricted, necessitating concentration of nutrition via Parenteral Nutrition posing an extravasation injury risk especially in the absence of central lines, a condensed version, posed greater error potential in prescribing practice. In addition to this it must be mentioned that consideration should be taken into account for those neonates depending on the pathophysiology of the disease that will impact upon the requirements of fluid and electrolytes. The most usual complications associated with TPN are the electrolyte imbalance, dehydration, clotting of blood, elevated or reduced level of blood sugar, infection, and hepatic failure. Therefore appropriate management of fluid and electrolyte administration should be considered that would depend upon the birth weight, corrected age and the gestational age. It should be noted that the calorific requirement of every patients depends upon the level of stress, failure of organ and in percentage of the actual weight of the body (Calkins, 2014). Extensive knowledge, in-depth understanding and critical thinking skills about Practitioner’s prescribing practice were essential to obtain certification and practice as a Non-medical prescriber. Prescribing within limitations of one’s knowledge, skills and experience was critical to patient safety and safe prescribing practice (RPS 2019), and, it was often required to update on emerging evidence in neonatal practice.

Continue your journey with our comprehensive guide to Newly Qualified Nurse Socialization.

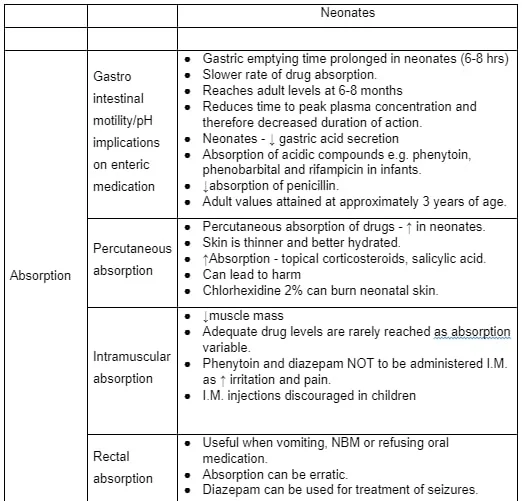

The absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion are significantly different in neonates (ADME-Table 2) from adults and children especially applied therapeutics. For example, topical drugs were avoided due to excessive absorption through thin, immature skin (General Pharmaceutical council [GPC] 2010). In Prescribers’ practice, every effort was taken to enhance quality of prescribing practice (NMC 2006 and RPS 2019), sought advice from DMP (NICE 2013) alongside resources for reference such as British National Formulary-Children, local hospital formulary and online resources despite elaborate knowledge with full knowledge of co-morbidities. Polypharmacy required monitoring renal and liver functions, and drug trough levels of nephrotoxic drugs namely Gentamicin, Vancomycin and Amikacin. Practitioner’s awareness of maternal medications (some were transmitted in breastmilk) and polypharmacy facilitated CMP amendments as necessary (Duerden 2013). An Audit Commission report on medicines safety called for introduction of hospital electronic prescribing systems as a priority but organisational (local) interest remained unclear, perhaps due to cost and training factors (NPSA 2009). The development of Personal formulary (Appendix 12) and Personal learning log (Appendix 6), DMP log (Appendix 4), NMC competencies (Appendix 3), DMP interim report (Appendix 1) and final report (Appendix 2), CMP and prescribing video evidence this learning outcome achievement (Appendix 8).

Discuss in depth the application of relevant legislation to the practice of prescribing and practice within a framework of professional accountability; acting as a role model for others.

Nurses constituted 95% of Non-medical prescribers are expected to be role models (Courtenay et al., 2012) as is in the practitioner’s role. Thus, in keeping with legislation (RPS 2019) and The Human Medicines Regulation Act (2012), practitioner gained knowledge and competence working towards prescribing qualification and demonstrated best practice in accordance with the RPS (2019) framework. The NMC competencies were achieved (Appendix 3). Non-medical prescribing improved patient care (neonatal care) and increased patient choices in accessing medicines with parental consent and participation in SDM guided by principles of medicines optimisation. For example, whilst making clinical management plans (CMP), the medication doses were optimized based on neonates’ current weight rather than previous weights. It was ensured that the right neonate received the right medication, right dose at the right time through multidisciplinary team approach. For example, CMP was made to stop Budesonide when it was no longer needed by a neonate (RPS 2013). Hence, clinical situations were judged by the Practitioner under consultant’s supervision, based on evidence in the best interest of neonates. Often, difficulties existed in development of age-appropriate formulations allowing use of some unlicensed and off-label medicines paying particular attention to risks namely adverse reactions and product quality (RPS 2019 & NMC guidance 2009). For example, a neonate required Propranolol oral medication for control of Supraventricular Tachycardia (SVT) and the Practitioner carried out a full assessment, to make a CMP for DMP approval. The use of Propranolol in neonates were referenced thoroughly and a legal requirement of a chemical component’s proportion (aqueous portion) was identified. Hence, pharmacist was involved to have the right concentration of Propranolol formulation for medicines optimization (RPS 2013). The Human Medicines Regulations Act (2012) enforced an initiative by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) to consolidate and review UK medicines legislation. NMC clarified on use off-label and unlicensed medicines as medicinal products which are not licensed for certain age group (neonates) owing to a lack of valid marketing authorisation (licence) in the UK. Caffeine citrate being an unlicensed medication in neonatal use, consultant approval was secured to use it to treat Apnoea of Prematurity. Bolam’s law was borne in mind while making the decision. Neonate was closely monitored for potential adverse effects and, accountability and responsibility were assumed by the Medical Prescriber.

The new competency framework is envisaged to support prescribers training to achieve qualification successfully to prescribe medication with optimal safety to patients (NICE 2006). It is envisaged that NMC competencies can help Non-medical prescribers remain effective and safe in their practice. This is evidenced by practitioner’s experience of acting as a role model as per RPS 2019 Framework of competencies. This promoted clinical effectiveness based on evidence, clinical guidelines, hospital formulary or BNF Children in line with the trust policies (GPC, 2010). Non-Medical Prescribing role granted autonomy, and benefited both services and neonates by allowing better access to medicines and smoother services’ delivery justifying this module whilst practising Prescribing within the framework of accountability (DoH 2006) and NICE (2015). Professional accountability and responsibility were evidenced in achievement of NMC competencies in Appendix 3 (NMC guidance 2009). Additionally, development of personal formulary, personal learning log and critical reflective evaluation evidence achievement of this learning outcome (Appendices 3, 12, 7 & 5).

Critically analyse the influences on prescribing practice including diverse and complex sources of information/advice and decision support.

Evidence suggests that decision-making and prescribing behaviours are complex with multiple, conflicting influences on decision-making (McIntosh et al., 2016). This has been the Practitioner’s experience. Despite evidence-based guidelines and treatment protocols, BNF Children reference, advice from medical practitioners, preferences from neonates’ parents and human factors- internal and external, influenced prescribing practice. It was viewed reasonable that parents had preferences, and shared decision-making took all influencing factors into consideration within safe prescribing practice optimizing neonate’s best interests (Ness et al. 2016). Human factors namely time pressures, task load on shift, mental and physical exhaustion especially night shifts and burnout had influenced prescribing practice by their negative impact on clinical judgement, decision-making and critical thinking skills (Wayne 2013). The practitioner experienced these pressures too but conscious efforts were taken to pay attention and reference information thoroughly whilst prioritizing tasks in hand. It was often required to invest more time to practice evidence-based CMP under supervision and critically analyse influences of human factors with self- awareness and analysis of own thought processes.

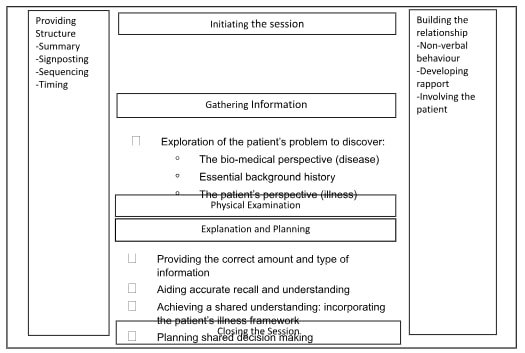

Heuristics such as representativeness heuristic and availability heuristic were misleading cognitive processes. Biases namely confirmatory bias and overconfidence hindered clinical judgements, but an awareness of these influences alongside system 1 and 2 thinking aided sound decision-making. Practitioner was conscious of the above and the resultant error potential was recognised (Klein 2005). The potential error that was being referred to here is the cognitive bias in the field of clinical medicine. As per 75% of the errors that were faced in the stream of internal medicine is of cognitive origin, which are divided into varied steps such as diagnostic phase, assortment of infection, provoking, context formulation and confirmation. Moreover there are other varied categories of bias in the clinical field such as availability bias, base rate neglect, confirmation bias, over confidence, representiveness, search satisfying, diagnostic momentum, framing effect, and commission bias. Thus, decisions were made based on current evidence on the use medications in neonatal practice to make an updated decision for evidence based practice in the field of nursing. Although the evidence in neonates is scarce, all the best available resources were searched and were critically analysed to make use of its contribution in the clinical field (Ioannidis, 2001). The Practitioner ensured that shared decision-making remained a focus and practitioner critically analysed influencing factors, acting in the best interest of neonates based on hierarchy of evidence, for example, meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials(Figure 2), facilitating evidence-based practice (RPS 2010). The decision to prescribe surfactant to a term baby with mild Respiratory Distress Syndrome was influenced by the above influences, leading to a dilemma, to prescribe or not to prescribe. It was clarified by comprehensive clinical assessment, detailed history taking, Chest X-ray interpretation and Radiologist’s report, decision support systems (Neonatal clinical guidelines), consultation with DMP and shared-decision making with parents of neonates. Team discussions have been helpful in complex clinical scenarios in the Practitioner’s experience. The holistic assessment informed diagnoses and enabled critical analysis of influencing external factors such as pharmaceutical company representatives including understanding of complex sources of information. Thus, the neonate had an opportunity to recover without surfactant prescription as a result of sound decision-making. There was, however, another scenario in which a neonate had Surfactant prescription and administration based on clinical assessment and presentation. As per scientific evidence, it is well common to prescribe exogenous surfactant therapy to new born babies who are suffering from respiratory distress. Respiratory Distress Syndrome (RDS) is the pathophysiological condition of acute respiratory distress where the exchange of gas gets hampered in a pre term babies with a typical clinical course or X – ray. It is also reported that the lungs of those babies are anatomically and biochemically very immature, therefore surfactant which normally present in the walls of the alveoli diminishes the surface tension and hinders the atelectasis. Therefore prophylactic surfactant theory assists to reduce the mortality rate (Lista, 2004; Sardesai, 2017). Hence, a different clinical decision was made because of the evidence supporting the prescription and the clinical signs required surfactant. There were multiple influences encountered on psychology of prescribing, with a focus on parents’ demands as opposed to neonate’s needs, overcoming peer pressures from Multi-disciplinary team and dilemma to prescribe or not to prescribe, which were clarified with evidence-based practice and readily available resources. Overcoming personal biases was feasible by critical thinking skills and prescribing in a team context whilst accounting for cultural and ethnic differences in prescribing practice justifying the decision (NMC 2018). Familiarity with BNF Children and unit guidelines, bearing Bolam’s law in mind facilitated CMP in practice. As it is evident that evidence based standard is inevitably defensible by Bolam and it considers the developing standards of care which are collectively utilised within the practice. Moreover, it is a professional formulated standard and do provide scope for genuine difference within the opinion and professionalism. It details about the strict professional rules for the evaluation of accurate standard of care with regard to the cases that had been dealt with negligence, by the skilled professionals like the physicians. In this way it follows the clinical management procedures. The challenges to success are also based on the past strong experiences and the presentation of excellent practice by employing Clinical Decision Support System. For instances Isabel is a web based diagnostic decision support developed by the physicians to offer support decision at the point of care. This system covers all the ages from neonates to geriatrics and also includes the specialists and all the sub specialists. CDSS are the digital based information centre that integrates the patient and their clinical findings to formulate appropriate decision making with regard to patient care services. These technologies are always helpful in the process of diagnostics, for the identification of alerts, planning of therapy, repossession of information, for the identification of image and elucidation (Mack, 2009). For example, parents of a neonate with severe early onset sepsis were unwilling to allow antibiotic administration but wanted a naturally healing stone to be placed beside the baby’s head (called it naturopathy). In this regard, it must be mentioned here, that the complementary and alternative medicine approach is considered to be a significant part of the healthcare system. However, its level of acceptance among the common populace has contributed to ethical dilemmas among the healthcare professionals. In this situation, the physicians and the nurses must educate the patients or their carers about the disease and the standard mode of treatment available, and also about the harmful effect or the inefficacy of the alternative medical treatment with regard to their opinion and results (Metcalfe, 2010). Therefore, a clear communication in between the patients or their carers diminishes the chances of practicing any questionable alternative treatment. This scenario required a senior involvement to facilitate concordance and adherence as it was a complex situation with baby diagnosed with Meningitis. Participation in clinical audits, risk management procedures, and systems monitoring processes, prescribing in a team context and public health context including public health policies and prevention of inappropriate use of medicines enhanced prescribing practice and patient safety (GPC 2010). Relevant patient record systems, prescribing and information systems, and decision support tools were used including regular reviewing of evidence underpinning therapeutic strategies with an understanding of framework for supplementary prescribing in line with Royal Pharmaceutical society (2019). Practitioner understood and demonstrated clinical judgement and decision-making based on evidence and decision support systems rather than directed by these influencing factors. Working within local frameworks for medicines use was possible with use of formularies, protocols and clinical guidelines, BAPM and NICE guidelines. This demonstrated best practice and an understanding of local and national guidelines in addition to discussion with senior colleagues (DMP log- Appendix 4). Practitioner was aware of scope of practice and the Practitioner’s competence was measured against reasonable expectations as per RPS framework (Stewart 2011 & Mark 2018) evidenced in prescribing video assessment. This learning objective was achieved by NMC competencies (Appendix 3), learning from DMPs (see DMP log- Appendix 4) and personal learning contract with SWOTs (Appendix 6), Personal learning log (Appendix 7), development of a personal formulary (Appendix 12) and critical reflective account (Appendix 5).

Demonstrate the ability to manage the implications of ethical dilemmas, and work proactively with others involved in prescribing, supplying and administering medicines to formulate solutions while prescribing safely, appropriately and cost effectively.

Neonates deserve medicines that have been appropriately tested although it has ethical dilemmas associated with it (Giacoia 2012). Appropriate testing yields an appropriate formulation, an appropriate dose and information about safety and efficacy. This information is lacking for most medicines given to neonates (Baer 2009). Therefore, it is agreed necessary to conduct clinical trials about medicines in neonates and the Practitioner’s unit participates in several clinical research projects including the Footprints study. The Practitioner has made CMP for neonates including those on Clinical research project and ensured that those projects had ethical clearance. Practitioner acknowledged and supported parental rights to withdraw from the study anytime to facilitate ethics in practice. The Practitioner has managed ethical dilemmas effectively under the supervision of DMP as evidenced by signed off competencies and supervised practice prior to final DMP report. CMPs considered cost-effectiveness by maintaining drug administration times to avoid medicines’ wastage. For example, when Vancomycin was due for administration at 06:00 hours and 18:00 hours, medication wastage could be avoided by sharing the vial among neonates receiving this drug as agreed by Trust’s clinical guidelines for medicines management alongside adherence to infection control measures. It is noteworthy, that some trusts do not advocate sharing of medication vials despite infection control strategies. The key to safe practice is to adhere to the local and trust guidelines on it. CMPs followed local policy of rounding dose to the nearest decimal point to minimise medication errors. For instance, Caffeine citrate dose for a neonate weighing 906 Grams at the dose of 10mg/kg was 9.06 milligrams. It was rounded off to 9.1 Milligrams in CMP as agreed by Pharmacists’ team and unit policy, thus managed an ethical dilemma, minimising medication errors. Caffeine is the most commonly used medication for the treatment of apnoea in case of pre matured babies. It is usually prescribed during the condition of discontinuous hypoxemia, along with extubation failure in mechanically ventilated pre term babies. However, there are certain controversies exist among the neonatal intensive care units, with regard to the efficacy of the medication in comparison to the routine dosage, introduction time, safety of the drug, duration of the therapy, methylxanthines, and the potential significance of drug monitoring. Therefore, all these situations cause an ethical dilemma while administering caffeine (Abdel-Hady, 2015). Practitioner had an understanding of parents’ experience and preferences, evidenced-based prescription of medicines, and making medicines’ use safe (RPS 2019). During the consultation and SDM process, practitioner respected patient autonomy, did good (beneficence), and avoided harm (non-maleficence) and did justice with CMP decisions in neonatal care (Good practice framework DoH 2001) whilst applying professionalism in prescribing cycle. Deontological ethics were demonstrated by respecting the neonates’/parents’ rights and focusing on the Practitioner’s duties, rules and obligations. Consequentialism was applied in prescribing practice by judging if something was right based on the outcome. Utilitarianism, greatest good for the greatest number of babies and Hedonism, judging something as good if it avoided pain were taken into account whilst formulating clinical management plans. As mentioned above, utilitarianism act helps in the undertaking of decisions after going through the nitty gritty of the individual case, to promote the cumulative better consequences. The neonatal professional faces a lot of challenges in terms of ethical aspects when concerned about interventions at the time of viability (weeks 22–25 of gestation). Varied types of challenges are faced within the neonatal profession, such as limit of viability, non-maleficence, beneficence (Hurwitz, 2004). However, it is also mentioned that maintaining both the principles of non-maleficence and beneficence are considered to be a challenging task. The encounter of tragic ethical predicament occurs in certain situations where there is no proper solution available that poses a threat to the professional ethics of the NICU team. It is also evident that the NICU teams operate most frequently at the limit of viability along with the susceptible infants and take their parents as surrogate decision makers. However, it is also clear that the major reasons that bring about the tragedy situations are the clinical indecision and the vagueness with regard to the best interest. There are several infants that survive with a minimum chance of survival and at that particular time the aspect of shared decision making is considered to be the acceptable methodology of choice (Stanak, 2019). Additionally, principles of respect for persons without autonomy (all neonates), veracity, confidentiality, fidelity and privacy were maintained through information governance, and a sense of legal and professional accountability (RPS 2016). The practitioner progressively gained skills to manage more complex ethical dilemmas based on current evidence, proactive discussions with consultants and by making clinical management plans in team context. For example, while making CMP for neonates, the Practitioner was aware of RPS competencies and sought senior colleagues’ approval when necessary. For example, the Practitioner sought for approval of clinical management plan of a neonate 22+4 weeks of gestation. It was a challenge right from the neonate’s birth. Both parents did not want interventions at delivery, perhaps, fearing suffering for the baby. However, baby was born in good condition with normal respiratory efforts and normal heart rate. As per clinical guidelines and assessment, neonate was started on Vapotherm (as per the clinical assessment and local clinical guidelines) with FiO2 of 30% and surfactant administration through Less Invasive Surfactant Administration (LISA) was necessary. The above ability was gradually developed by DMP time, personal learning activities and enhanced team communication (Cristie 2017). CMP was made in line with RPS framework within the scope of practitioner’s role. This included formulation and documentation of clinical management plans along with Independent Prescriber, record keeping, Yellow Card reporting to the Committee of Safety on Medicines (CSM) and reporting patient/client safety incidents to the National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA) and informed consent. In this case, consent for neonatal care involved providing clear information and building trust between the Practitioner and parents beginning antenatally (BAPM-DRAFT 2019). In the Practitioner experience, shared decision-making has been satisfactory evidenced by Parent experience surveys (Appendix 11) and parents agreement with the clinical management plan with the help of shared decision-making. Thus, ANNP role achieved the above in NICU to enhance cost-effectiveness (DoH 2001 & 2002). To achieve the cost effectiveness during the nursing procedure, the cost effectiveness focuses on the individual choices, by making proper decision based on informed decision and evidence based practice. They also help to formulate informed judgements. However, few limited information are available on the cost effectiveness practices of the nurses. One particular measure to practice cost effective prescribing is the providing the patient with a generic medication when another one is available. Moreover, it is also reported that physicians and NMPs do not receive official training on the cost effective prescribing practices. Therefore, for the healthcare professionals to practice cost effective prescribing, they need more sophisticated tools (Isetta, 2013). Integration of services through ANNP role demonstrated teamwork and multi-professional co-operation including specialist nurses, pharmacists and doctors, and the ability to work together (Stuttle 2010). This, however, requires further research. Well-organised team structure was critical for successful teamwork to manage clinical implications of legal, ethical and policy aspects at local and national levels.

Evidence suggests that Nurse prescribing rendered cost-effectiveness with non-medical prescribers having saved the NHS in England an estimated annual £777 million through Prescribing practice (NHS Health Education North West 2015). Patients (Parents) reported higher levels of satisfaction with, and confidence in, nurse prescribers due to their levels of specialist knowledge, experience with relevant treatments and recognition of their own limitations. It is noteworthy that, despite documented benefits, a secondary analysis of a national primary care prescription database revealed merely 1.5% of total prescriptions were prescribed by Nurses in primary care in 2010 (Drennan 2014).

National NHS frameworks for medicines use NICE, medicines management, clinical governance, IT strategy which were more familiarised during DMP time (Appendix 4). Thinking/acting as part of a multidisciplinary team ensured continuity of care. This was demonstrated in practice evidenced by DMP intermediate and final reports (Appendices 1 & 2), NMC competencies (Appendix 3), DMP and personal log (Appendices 4 & 7), recorded shadowing time with Pharmacists and DMPs and Critical reflective account (Appendix 5). The professional accountability in the field of nursing depends on the factors like the quality of their work, their accountability to the health organisation. There are constitutively four pillars: first one is the professional accountability; second one is the ethical accountability, third one is the legal accountability, and the fourth one is employment accountability. The nurses should demonstrate the duty of care which is a legal application to adhere to the standard treatment. This is considered to be the first element that should be considered in case of any negligence. In this regard the Misuse of Drugs Act should be discussed which is considered to be the principle legislation for drug related offences. The misuse of drug is associated with the use of some commonly used drugs which are unlicensed, or other addicting substances. Therefore this part belongs to the medicine management of the nurses, and nurses are highly accountable for the right administration of medication that would ensure patient safety and security (Bath-Hextall, 2011; Altranais, 2003; Monaghan, 2014).

References:

Allegaert K (2018) Rational Use of Medicines in Neonates: Current Observations, Areas for Research and Perspectives. Healthcare Journal.Sep; 6(3): 115.Published online 2018 Sep 14. 2018

Baer GR. Ethical issues in neonatal drug development in Pediatric drug development: Concepts and Applications, eds Mulberg AE, Siber SA, Van den Anker JN, USA: John Wiley and Sons, 2009: 103-13

Benner P. From Novice to Expert. Menlo Park, Calif: Addison-Wesley; 1984.

Bissell P, Cooper R, Guillaume L, Anderson C, Avery A, Hutchinson A, James V, Lymn J, Marsden E, Murphy E, Ratcliffe J, Ward P, Woolsey P. An Evaluation of Supplementary Prescribing in Nursing and Pharmacy. London: Department of Health; 2008

Bordage G. Elaborated knowledge: a key to successful diagnostic thinking. Journal of Academic Medicine. 1994;69: 883- 885.

British Pharmacological Society. Ten principles of good prescribing, https://main.bps.ac.uk/SpringboardWebApp/userfiles/bps/file/Guidelines/BPSPrescribingPrinciples.pdf

Clark C (1999) Taking a history. In Walsh M, Crumbie A, Reveley S (Eds) Nurse Practitioners: Clinical Skills and Professional Issues. Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, 12-23

Courtenay M, Carey N. Nurse independent prescribing and nurse supplementary prescribing practice: national survey. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2008; 61: 291-9.

Courtenay M, et al.(2012) An overview of non-medical prescribing across one strategic health authority: a questionnaire survey. Journal of BMC Health Services Research 2012; 12: 138.

Department of Health. Allied Health Professions Prescribing and Medicines Supply Mechanisms Scoping Project Report. London: Department of Health; 2009.

Department of Health. Proposals to introduce prescribing responsibilities for paramedics: stakeholder engagement. Consultation paper. London, Department of Health, 2010.

Department of Health. Improving patients’ access to medicines: A guide to implementing nurse and pharmacist independent prescribing within the NHS in England. London: UK Department of Health, 2006.

Dimmond B (2011) Legal Aspects of Medicines (2nd Edition), London: Quay Books

Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety. Northern Ireland Medicines Optimisation Quality Framework. March 2016 https://www.health-ni.gov.uk/sites/default/files/consultations/dhssps/medicines-optimisation-qualityframework.pdf

DoH (1989). Report of the Advisory Group on Nurse Prescribing (Crown report). London.

DoH (2000). A Health Service of All the Talents: Developing the NHS Workforce. London.

DoH (2001). Essence of Care. London.

DoH (2002). Liberating the Talents. London Stationery Office.

DoH (2008). High Quality Care for All: NHS Next Stage Review Final Report. London.

Drennan V, et al. Trends over time in prescribing by English primary care nurses: a secondary analysis of a national prescription database. Journal of BMC Health Services Research 2014;14:54.

Duerden M, Avery T, Payne R. Polypharmacy and Medicines Optimisation. Making it safe and Sound. Kings Fund 2013. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/polypharmacy-and-medicines-optimisation

Epstein RM: Mindful practice. JAMA 1999, 282:833–838

FitzGerald RJ (2009) Medication errors: the importance of an accurate drug history. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2009 Jun; 67(6): 671–675

General Pharmaceutical Council (2010). Indicative Curriculum for the Education and Training of Pharmacist Independent Prescribers. London: GPhC;

Giacoia GP, Taylor-Zapata P, Zajicek, A, Drug studies in newborns: a therapeutic imperative, Clin Perinatol 2012; 39: 11-23.

Haynes RB, Ackloo E Sahota N McDonald HP and Yao X (2008) Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Issue 2. Art. No CD000011.

Klein JG (2005). Five pitfalls in decisions about diagnosis and prescribing. BMJ. Apr 2;330(7494):781-3.

Latter S, Blenkinsopp A, Smith A, Chapman S, Tinelli M, Gerard K, Little P, Celino N, Granby T, Nicholls P, Dorer G.(2010) Evaluation of Nurse and Pharmacist Independent Prescribing. London: Department of Health.

List Baxter K (2012) Stockley's Drug Interactions Pocket Companion. Pharmaceutical Press British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain (current version) British National Formulary & or BNF for Children Oxford, Pharmaceutical Press. Pg.7

Lloyd H, Craig S (2007) A guide to taking a patient’s history. Nursing Standard. 22, 13, 42-48

Mark G (2018) Legal and Ethicalaspects in nurse prescribing. Journal of Nurse Prescribing (16): 4.Published Online: 11 Apr 2018

McIntosh T, Stewart D, Forbes-McKay K, et al. (2016) Influences on prescribing decision-making among non-medical prescribers in the United Kingdom: systematic review. Journal of Family Practitioners 2016; 33: 572–579.

Moulton L (2007). The Naked Consultation: A Practical Guide to Primary Care Consultation Skills. Radcliffe Publishing, Abingdon

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2016). Multimorbidity: clinical assessment and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/indevelopment/gid-cgwave0704

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2015). Medicines optimisation: the safe and effective use of medicines to enable the best possible outcomes. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng5

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2009) Medicines Adherence: Involving Patients in decisions about prescribed medicines and supporting adherence. NICE Clinical Guidelines

https://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG76NICEGuidelineWord.doc

National Institute for Health Care Excellence (2016) A Single Competency Frameworkfor all Prescribers

National Patient Safety Agency (2009) Safety in Doses: Medications safety incidents in the NHS.

National Prescribing Centre (2012). A single competency framework for all prescribers.

National Prescribing Centre (2001). Maintaining Competency in Prescribing. An outline framework to help nurse prescribers. First Edition.

National Prescribing Centre (2003). Maintaining Competency in Prescribing. An outline framework to help nurse supplementary prescribers. March 2003.

National Prescribing Centre. A single competency framework for all prescribers. National Institute for Health and Clinical excellence

https://cfna.org.uk/3309trV/prescribers_competency_framework.pdf

NHS Health Education North West (2015). Non-medical prescribing (NMP). An economic evaluation.

Nursing and Midwifery Council (2006) Standards of Proficiency for Nurse and Midwife Prescribers. London, Nursing and Midwifery Council.

Nursing and Midwifery Council (2009) Standards of Proficiency for Nurse and Midwife Prescribers. London, Nursing and Midwifery Council.

Royal College of Nursing (2014). RCN fact sheet: Nurse prescribing in the UK.

Stewart D, MacLure K, George J (2012). Educating non-medical prescribers. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology ; 74: 662–667

Royal Pharmaceutical Society (2014). Medicines optimisation: helping patients to make the most of medicines. https://www.rpharms.com/promoting-pharmacy-pdfs/helping-patients-make-the-most-of-their-medicines.pdf

Silverman J, Kurtz S, Draper J (2004) Skills for Communicating with Patients. Second edition. Radcliffe Publishing, Abingdon

Stewart K et al. (2012) Educating nonmedical prescribers. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2012 Oct; 74(4): 662–667.

Stuttle B (2010) Non-medical prescribing in a multidisciplinary team context. Cambridge University Press. pp 7-14

While A (2002) Practical skills: prescribing consultation in practice. British Journal of Community Nursing. p7, 9, 469-473

World Health Organisation (2007) Promoting Safety of Medicines for Children, World Health Organisation.

World Health Organisation (2015) WHO Global strategy on people-centred and integrated health services: interim report.

Wayne Robson (2013) Prescribing errors: taking the human factor into account. Better Practice Nurse Prescribing: Vol. 11, No. 9.

https://www.rdforum.nhs.uk/content/2012/08/14/human-medicines-regulations-2012-come-force/

https://www.nmc.org.uk/globalassets/sitedocuments/circulars/2009circulars/nmc-circular-02_2009-annexe-1.pdf

https://www.magonlinelibrary.com/doi/abs/10.12968/npre.2017.15.12.594

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5499356/

https://nuffieldbioethics.org/assets/pdfs/CCD-Short-Version.pdf

https://www.bapm.org/resources/78-draft-enhancing-shared-decision-making-in-neonatal-care-a-framework-for-practice-2019

Placencia, F.X. and McCullough, L.B., 2011. The history of ethical decision making in neonatal intensive care. Journal of Intensive Care Medicine, 26(6), pp.368-384.

Abbe, M., Simon, C., Angiolillo, A., Ruccione, K. and Kodish, E.D., 2006. A survey of language barriers from the perspective of pediatric oncologists, interpreters, and parents. Pediatric blood & cancer, 47(6), pp.819-824.

Dersch-Mills, D., Akierman, A., Alshaikh, B. and Yusuf, K., 2012. Validation of a dosage individualization table for extended-interval gentamicin in neonates. Annals of Pharmacotherapy, 46(7-8), pp.935-942.

Swinglehurst, D., Greenhalgh, T., Russell, J. and Myall, M., 2011. Receptionist input to quality and safety in repeat prescribing in UK general practice: ethnographic case study. BMJ, 343.

Cushing, A. and Metcalfe, R., 2007. Optimizing medicines management: From compliance to concordance. Therapeutics and clinical risk management, 3(6), p.1047.

Benterud, T., Sandvik, L. and Lindemann, R., 2009. Cesarean section is associated with more frequent pneumothorax and respiratory problems in the neonate. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica, 88(3), pp.359-361.

Calkins, K.L., Venick, R.S. and Devaskar, S.U., 2014. Complications associated with parenteral nutrition in the neonate. Clinics in perinatology, 41(2), pp.331-345.

Ioannidis, J.P. and Lau, J., 2001. Evidence on interventions to reduce medical errors. Journal of general internal medicine, 16(5), pp.325-334.

Lista, G., Colnaghi, M., Castoldi, F., Condo, V., Reali, R., Compagnoni, G. and Mosca, F., 2004. Impact of targeted‐volume ventilation on lung inflammatory response in preterm infants with respiratory distress syndrome (RDS). Pediatric pulmonology, 37(6), pp.510-514.

Sardesai, S., Biniwale, M., Wertheimer, F., Garingo, A. and Ramanathan, R., 2017. Evolution of surfactant therapy for respiratory distress syndrome: past, present, and future. Pediatric research, 81(1), pp.240-248.

Mack, E.H., Wheeler, D.S. and Embi, P.J., 2009. Clinical decision support systems in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, 10(1), pp.23-28

Hurwitz, B., 2004. How does evidence based guidance influence determinations of medical negligence?. Bmj, 329(7473), pp.1024-1028.

Stanak, M., 2019. Professional ethics: the case of neonatology. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy, 22(2), pp.231-238.

Abdel-Hady, H., Nasef, N. and Abd Elazeez Shabaan, I.N., 2015. Caffeine therapy in preterm infants. World journal of clinical pediatrics, 4(4), p.81.

Isetta, V., Lopez-Agustina, C., Lopez-Bernal, E., Amat, M., Vila, M., Valls, C., Navajas, D. and Farre, R., 2013. Cost-effectiveness of a new internet-based monitoring tool for neonatal post-discharge home care. Journal of medical Internet research, 15(2), p.e38.

Metcalfe, A., Williams, J., McChesney, J., Patten, S.B. and Jetté, N., 2010. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by those with a chronic disease and the general population-results of a national population based survey. BMC complementary and alternative medicine, 10(1), p.58.

Bath-Hextall, F., Lymn, J., Knaggs, R. and Bowskill, D. eds., 2011. The new prescriber: An integrated approach to medical and non-medical prescribing. John Wiley & Sons.

Altranais, B., 2003. Guidance to Nurses and Midwives on Medication Management, June 2003. An Bord Altranais.

Monaghan, M., 2014. Drug Policy Governance in the UK: Lessons from changes to and debates concerning the classification of cannabis under the 1971 Misuse of Drugs Act. International Journal of Drug Policy, 25(5), pp.1025-1030.

file:///C:/Users/DEBASMITA/Downloads/Validation_of_a_Dosage_Individualization_Table_for.pdf https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4959632/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15846701/ https://www.rcpe.ac.uk/sites/default/files/jrcpe_48_3_osullivan.pdf https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2722820/ https://www.bmj.com/content/suppl/2004/10/28/329.7473.1024.DC1 https://opentextbc.ca/clinicalskills/chapter/8-8/ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6626201/ https://www.rch.org.au/rchcpg/hospital_clinical_guideline_index/Neonatal_Intravenous_Fluid_Management/ https://www.who.int/medicines/publications/essentialmedicines/Promotion_safe_med_childrens.pdf?ua=1 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5710987/ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2387303/ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6499733/SDM participation- factors and strategies to promote parents’ participation

Absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion (ADME)

The Calgary- Cambridge consultation Model

The hierarchy of evidence

Continue your exploration of Importance and Implementation of Pressure Ulcer Prevention in Nursing with our related content.

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts