Examining Day-Specific Self-Control Demands and Psychological Well-being

Nonparametric Correlations

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 22.0 (SPSS Inc.). For Test 1, group effects were assessed with separate Multi level Variation with planned follow-up contrasts (Fisher’s LSD), with effect size for observed significant main effects reported with ETA2 (η2). Note that for this measure of effect size, .01 is considered to be a small effect, .06 = medium, .13 = large [39]. Follow up group contrasts (that is, when directly comparing one group to another) effect sizes are reported with Cohen’s d (calculated from estimated marginal means: Mean1-Mean2/Pooled SD, where .2 = small effect, .5 = medium, .8 = large [39]). For Test 2, improvement in cognitive control was assessed with a linear mixed model repeated measures analysis, with subject acting as a random effect. For this analysis, a compound symmetry correlation structure among repeated measures was used to compare pre to post performance. Planned follow-up contrasts were constructed for each mixed model to directly assess changes within each group, with the effect sizes of these within-group changes reported via Cohen’s d. We also calculated the estimated marginal mean gain score (pre-post/post-pre) to further understand significant interactions from the mixed model analysis. To minimize influential data points, we removed values +/- 2 standard deviations for all group analyses. For correlations tested in Experiment 2, we used a more stringent outlier removal procedure (Cook’s D > 1 [40]) given the smaller cohort size and possible inflated change scores. Those who need assistance may consider seeking statistics dissertation help. De-identified individual scores for Experiment 1 and 2 are presented in the S1 Dataset.

Discussion

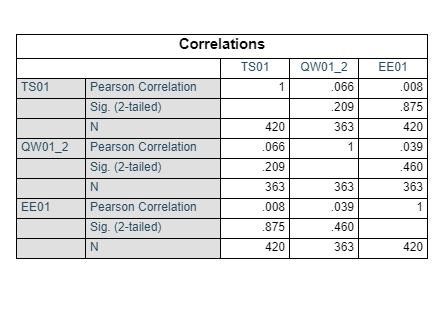

Research on tax complexity, role conflict and self-control strongly suggests that demands on self-control and the associated depletion of regulatory resources are negatively related to psychological well-being. Also, there is initial evidence that shows that SCDs may fluctuate from often and that these day-specific SCDs draw on and deplete limited regulatory resources (Muraven et al., 2005). On the basis of these propositions, we examined the relationships between job-related day-specific SCDs and day-specific indicators of psychological well-being. Additionally, we sought to identify moderators that may determine day-specific availability, as well as usage of limited regulatory resources, which thus have the potential to attenuate the negative relations of day-specific SCDs and psychological well-being. Our results indicate that SCDs exhibit day-specific fluctuations that are related to day-specific changes in indicators of well-being. More precisely, on days with high SCDs, employees are more likely to suffer from increased ego depletion and need for recovery and impaired work-engagement compared with low day-specific SCDs. in addition, consistent with the SDT and the broaden and build theory of positive emotions, we demonstrate that affective commitment attenuates the day-specific negative relationships between SCD5 and psychological well-being. Thus, when SCDs are high, strongly committed employees are less susceptible to impairments in psychological well-being because of SCDs compared with less committed employees. In summary, as predicted, affective commitment can protect employees from the adverse effects of day-specific SCDs. 5.1

Theoretical implications

Our study contributes to the literature on self-control in multiple ways. First, we complement previous studies that examined SCDs as stable attributes of work by providing initial evidence for day-specific variations in work-related SCDs. Thus, in addition to the in terindividual variations of SCDs, our research also demonstrates the intraindividual day-specific variations of SCDs that may be related to day-specific events at work that require employees to exert self-control.

Second, consistent with the limited strength model of self-control, our study provides initial evidence for negative relationships between job-related day-specific SCDs and psychological well-being. Thus, our research complements findings on the adverse impact of job-specific SCDs on long-term indicators of well-being (e.g., Diestel & Schmidt, 2011) by also demonstrating that day-specific SCDs are negatively related to day-specific psychological well-being. It is possible that previous results concerning the adverse effects of global job-specific SCD5 on interindividual indicators of psychological well-being may be determined, at least in part, by day-specific relationships between SCDs and indicators of psychological well-being.

Third, consistent with the SDT, our research suggests that commitment fulfills employees' basic psychological needs (autonomy, competence and relatedness) and demonstrates the buffering effects of commitment on the adverse day-specific relationships between SCDs and indicators of psychological well-being. Thus, our findings complement previous research on organizational resources that buffer the adverse consequences of SCDs (e.g., job-control and goal conflicts; cf. Schmidt & Diestel, in press).

Looking for further insights on Evaluating the Treatment Landscape for Depression? Click here.

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts