The Impact of Technology and Globalization on Retail Strategies

introduction

Technology, globalization and increased competition have forced retailers to innovatively contact their customers and market their products. Observably, technology has also revolutionized the way retailers do business, with new ways of advertising, marketing and delivering products to customers. More importantly, there is an increasing need for retailers to embrace the omnichannel retailing to constantly understanding the needs of customers. According to Chatteriee & Kumar (2017), omnichannel retail or marketplace entails constantly being in contact with customers through various communication channels including live web chats, telephone communication, social media, mobile applications and physical locations. Proponents of this concept hold that customers are supposed to be in constant knowledge of any relevant information pertaining to the products or services of a company, and this can only be achieved through a multichannel communication. If you require further insights or assistance, seeking marketing dissertation help can provide valuable guidance in navigating these complex topics.

The retail industry for luxury products is undergoing a rapid change especially in the presence of social media and other technological enablers for e-commerce. As a result, players in the fashion industry, even the prominent ones like Gucci, are constantly under pressure to step up their marketing initiatives to ensure they are ‘seen’ by customers from all demographics (Sebald & Jacob 2017). More importantly, luxury fashion retailers are increasingly gaining an edge on the transformation process of their online marketing initiatives to resemble their offline exclusivity. This is due to the realization that just creating exclusive products and showcasing them on the shelves and runways is not enough to stage the most desired level of competitiveness.

This report will explore how luxury brands use online touch points to communicate to their consumers. It will evaluate the development of the omnichannel as enabled with global digitization and how this development has changed the customer experience and turned customer’s attention to online channels.

While Kapferer (2014) asserts that marketers are changing from multichannel to omnichannel, Verhoef et al (2017) argue that omnichannel is more than simply using a mix of social media and mobile for marketing. Thus, it comes out clearly that modern marketing involves various touch points which are interconnected that eliminates the distinction between online and offline channels.

This report will examine how shifting from offline to online platforms has affected consumer behavior, especially bearing in mind the argument by marketing experts that integrating channels promotes a company’s value proposition (Saunders et al 2012). In doing so, there will be an attempt to understand how online channels promote customer experience with luxury brands and what the brands can do to meet customer expectations. Hence, the research question to be answered is: How can luxury brands create an omnichannel approach by use of platforms that enhance their range and image?

The conceptual framework

Digitization has brought a complete change in the way participants in the luxury market conduct their sales and marketing. In fact, according to Baker et al (2018), luxury brands are rapidly embracing online platforms as their major sales channels globally. Furthermore, McCormick et al (2014) propose that the online marketplace for luxury products will receive a 5% growth in the period between 2018 and 2020. Despite this experienced and expected growth, some luxury brands, for example, Gucci, are not determined to grow their online sales but rather grow their sales in general. This is illustrated in the 2016/2017 Gucci annual reports where there was a clear articulation of the fact that the company wants more consumers to research their products, discover their brand and purchase their products either in-store or online. Hence, as Belu & Marinoiu (2014), Molla-Descals et al (2014) and Gerrikagoitia et al (2015) argue, digital channels have evolved to be more of luxury brands’ tools for sales support than a platform for directly transacting with customers.

Customer Attitude

In most cases, consumers of luxury products shy away from purchasing expensive products online because they prefer looking at the product and feeling it (Faulds et al 2016). Hence, as Willems et al (2017) put it, online tools are only often used for inspiration, comparing prices, and weighing options before making the actual purchase. Likewise, as suggested by Chatterjee & Kumar (2017), the audiences and purposes of each digital platform are different, making it necessary for luxury brands to understand how they can optimally use each platform for their own benefit. Consequently, marketers of luxury brands are increasingly gaining proficiency in each platform and ensuring that their marketing messages are tailored to each audience and platform (Sebald & Jacob 2018).

E-commerce in the Luxury Retail

According to Verhoef et al (2017), luxury brands tend to use the concept of e-commerce in a slightly different way that other categories of retailers. To support his argument, the author states that while other retailers of normal products use e-commerce majorly for sales purposes, retailers of luxury brands use e-commerce for sales purposes as well as for communicating their range and image. Equally, according to Saunders et al (2012), luxury brands are increasingly using e-commerce to communicate more information about their products than they do in-store. This is based on the argument that consumers tend to research online for comprehensive information about the product and failure to acquire such information may make them turn to another retailer (Li et al 2017). At Gucci, the integration of both online and offline retail occurs both internally and externally. For instance, Baker et al (2018) observe that as consumers come to the store with images of the products they intend to buy, the stores gradually understand the idea and importance of both online and offline marketing. Equally, to give a better understanding of the luxury consumer in the context of omnichannel retail, Molla-Descals et al (2014) remark that today’s consumer is aware of all the product specifications including the price, color, and model even though the in-store personnel have the responsibility of showing the customer all these details. This implies that today’s consumers of luxury products are omnichannel and luxury brands such as Gucci have no option but to invest more on the omnichannel to meet customer expectations.

Objectives and Aim of the Study

Luxury brands are exclusive brands. According to Rodriguez et al (2017), what makes luxury brands luxurious is the fact that they are admired by many but consumed by a few. Consequently, some marketers in the luxury retail argue that the internet is not a good marketing platform for luxury brands because the brand value perceptions of the brand may diminish. Proponents of this argument also tend to avoid the internet because it provides too much online availability to maintain the prestigious image (Li et al 2017). Nonetheless, Verhoef et al (2017), Molla-Descals et al (2014) and McCormick et al (2014) observe that consumer behavior has changed and more of them are increasingly embracing online platforms for interacting with luxury brands. Therefore, if luxury brands fail to increase their online presence, then they stand a chance to lose out on more sales. This, perhaps, is the reason why luxury brands such as Gucci have increased their digital presence.

The internet has become a useful tool for nearly all, if not all sales and marketing initiatives for luxury brands. For instance, Rodriguez et al (2017) argue that luxury brands depend on the internet for executing communication strategies, to enhance and improve customer experience, and to enhance brand loyalty. While these uses of the internet add on to the global interest of the internet as a powerful marketing enabler (Li et al 2017), Saunders et al (2012) and Molla-Descals et al (2014) acknowledges a paucity of research on digital marketing with a specific interest in luxury products. Particularly, Rodriguez et al (2017) opine that while several studies have largely concentrated on multichannel marketing, a few have concentrated on omnichannel platforms and the strategies that can enable luxury brands to successfully present their range and image. Hence, the first objective of this study is to identify the various strategies used by luxury brands to ensure that they gain success on digital channels. Of focus are the digital channels such as e-commerce, websites and social media sites (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat, and Youtube)

Consumer experience is an important aspect of marketing, regardless of whether it is in the context of luxury products or ordinary products. Li et al (2017) defined consumer experience as the manner in which customers interact with the product or service being offered. The scholar further explains that consumers, especially those on of luxury brands, expect an exclusive experience with luxury brands. While several studies Molla-Descals et al (2014), Verhoef et al (2017), McCormick et al (2014), Molla-Descals et al (2014), Baker et al (2018) and Kapferer (2014) have been initiated to explore the concept of customer experience and how it can be improved, most of them have taken a general perspective, with little focus on luxury brands. Furthermore, Rodriguez et al (2017) articulately acknowledge a paucity of research on the expectations customers have while interacting with luxury brands online. Hence, the second objective of this study is to investigate the consumer expectations of luxury brands online experience. Ultimately, the study will explore how luxury products can improve their omnichannel marketing position.

Research Philosophy

In writing, McCormick et al (2014) argued that research philosophy is the researcher’s adopted beliefs upon which knowledge is acquired during the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data. According to Pallant (2010), these beliefs can be anchored on several methods such as positivist, realism, interpretivism, and pragmatism. To have an amicable understanding of how Gucci presents its image and ranges both online and offline, the report will take the interpretivist approach. This philosophy holds that the researcher interprets various elements of the study, integrating their human interest into the entire study process (Pallant 2010). In doing so, the report will assume that the reality of how Gucci presents its range and image in the omnichannel marketplace can be obtained through consciousness, language, instruments and shared meanings; relying more on qualitative analysis rather than quantitative analysis (McCormick et al 2014).

Ethical Considerations

The study will rely on various ethical principles to ensure that it upholds the highest ethical standards. Firstly, as recommended by Pallant (2010) the respondents’ consent will be obtained before taking exposing them to the interviews. Secondly, the confidentiality and anonymity of the respondents’ information will be protected. Similarly, all the respondents will be granted the opportunity to withdraw from the exercise.

Research Design

The study will adopt a mixed methodology approach, where both primary and secondary data will be used. Secondary data will be collected from previous studies as well as company reports of Gucci, while primary data will be collected through interview questions. Majorly, there will be a customer survey to have direct information from them on their online and offline experiences with Gucci. The study will involve an online interview of five customers of Gucci, and their quotes will be recorded for further analysis. On the other hand, secondary data (previous research and online company reports) will enable a comprehensive literature review of the study (Bryman & Bell 2015). The report will also involve a subjective analysis of different company websites to make relevant conclusions and achieve research objectives. Finally, the study will compare findings from primary data with those achieved from secondary data to answer the research question.

Method of Data Analysis

The data will be analyzed by identifying major themes and trends emanating from secondary data and answers from the interview survey. The thematic analysis will be a continuous exercise throughout the research. According to Saunders et al (2012), thematic analysis is the process of identifying, recording and interpreting qualitative data in order to answer the research questions at hand. Thematic analysis is important in identifying and describing various trends on a research topic especially when dealing with specific research questions. Hence, the study will adopt thematic analysis to identify how Gucci presents their image and ranges in the omnichannel marketplace.

Research Findings

The survey was administered online and involved 10 respondents who answered questions show in sample questionnaire (Appendix 1). The respondents were mostly Europeans and only those from the UK were asked to participate because Gucci employs different strategies in different geographical areas. The age range was from 25 to 50 years, capturing data from current and future consumers of luxury products. Furthermore, according to Verhoef et al (2017), Gucci’s current consumers are mostly the millennials, a demography currently targeted by most marketers of both luxury and ordinary products. Among the respondents, 4 were male and 6 were female; hence this report may be more biased towards the female gender. All in all, the fact that a majority of the respondents were millennials means that the results may be used to understand the future consumers of luxury products rather than the current ones, even though both young and old generations use digital platforms to interact with luxury brands (Saunders et al 2012).

As illustrated in Appendix 1, the questionnaire questions were specifically designed to (i) to understand the expectations of customers with regards to how they interact with luxury products online (ii) to identify how luxury products can improve their omnichannel marketplace and (iii) to explore the strategies used by luxury brands to ensure a successful omnichannel presentation of their range and image. This necessitated an investigation of consumer online shopping behavior and brand loyalty of luxury products. Secondly, it was necessary to investigate how consumers use different online channels and consumer perceptions of how useful they are.

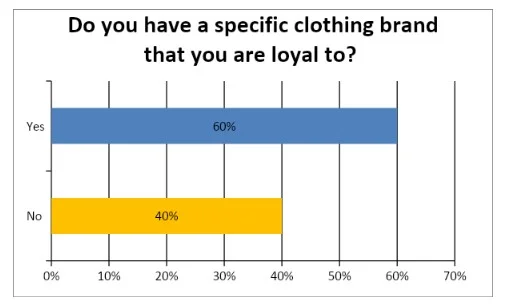

To investigate the online consumer shopping behavior and brand loyalty of luxury products, respondents were asked whether they had a specific brand which they stick to every time thy shop for luxury clothing. A majority of the respondents (60%) did not have a specific brand while 40% were loyal to one specific brand (fig 1). Moreover, a majority (60%) agreed to have bought luxury products online (fig 2), even though only a few (20%) preferred to use online platforms for this purpose (fig 3). Nevertheless, 40% said that they prefer either online or offline channels for purchasing different kinds of luxury products (fig 4). To have a deeper understanding why consumers may not prefer online channels for purchase of luxury products, the respondents were asked to give their opinion and the results revealed that consumers may not prefer to do an online purchase for luxury products due to lack of feel and touch experience and preference to have the product on hand immediately after purchase.

Fig 1

Fig 1

Fig 1

Fig 1

Fig 1

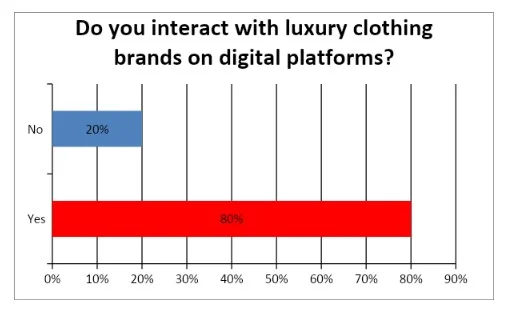

To investigate consumer digital interaction with luxury products, the respondents were asked to whether they interact with luxury products online. A majority of them (80%) acknowledged that they interact with luxury brands through different channels including Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Youtube, e-commerce, and brand websites (fig 5).

To investigate consumer digital interaction with luxury products, the respondents were asked to whether they interact with luxury products online. A majority of them (80%) acknowledged that they interact with luxury brands through different channels including Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Youtube, e-commerce, and brand websites (fig 5).

When asked how frequent they use any of the platforms; Facebook, Instagram, brand website and brand e-commerce appeared to be the most frequently used. On the other hand, other platforms such as apps and Youtube appeared to be less used. To specifically understand of how consumers use their preferred platforms, they were asked to describe how they use the platforms and a majority of Facebook users used it for viewing product images while those who used brand website used them for gaining specific information about the products. Equally, e-commerce was majorly used to make purchases.

Consumer expectations of online experience

The survey reveals that despite using online channels to purchase products, a majority of shoppers do not prefer online channels for making purchases. This is often for the reason that most consumers want to feel or see the product physically before making the actual purchase. This is despite the fact that luxury products have seen an increase in purchases done through e-commerce platforms according to reports released by (Li et al 2017).

To explore why consumers may not be satisfied by the online experience, we asked them to give their reasons why they never enjoyed the online experience and some of the cited lack of adequate information online, revealing that while online platforms are majorly useful in providing all manner of information to consumers, some brands have not yet optimized them for the same purpose. Verhoef et al (2017) also had the same findings where he noticed that some luxury products fail to avail adequate and accurate information about their products online, making consumers to consider competitor brands.

Similarly, some respondents were of the opinion that most luxury brands have failed to deliver their offline exclusivity online and that the concept of ‘luxury’ could be better realized offline than online through exterior and interior shop design, high-level customer assistance and the general look of the stores. According to these respondents, the offline experience of luxury brands is more satisfying than online experience, triggering a need for the brands to improve their online luxury service provision. All in all, the survey revealed that level of customer satisfaction with the online experience varies from brand to brand, with most respondents having different satisfaction levels with different brands.

A few respondents also complained that most brands fail to immediately interact with customers on their online platforms, despite the availability of many options to do this. As Rodriguez et al (2017) put it, interacting with consumers can be quite easy when tools such as live chat or instant messaging are put into use. However, as revealed by the survey, some luxury brands fail to use such tools. Hence, it comes out clearly that consumers of luxury brands expect more product information, personalization and online interaction with the brand through instant messaging and live chats; and provision of exclusive online services similar to those provided offline (fig 6). Therefore, if Gucci provides sufficient information, personalizes its online client interaction and improves its exclusive online services, it shall have improved its digital presentation of image and range.

Strategies for digital success

Findings from secondary data reveal that all luxury brands, at least those considered in this study had a website. According to McCormick et al (2014), consumers of luxury brands first visit the company website before moving to any other online platform. As such, most luxury brands primarily use the website to control their brand image before rolling out the initiative into other online platforms. Upon visiting the website, consumers may also visit the brand’s social media platform especially when a link is provided on the website. This is the reason why Gucci provides links to their e-commerce and social media platforms on the website. According to Baker et al (2018), providing the links explains the strategy of cross-channel integration which is applied by the brand to build brand loyalty.

Observably, Gucci, Buberry, Prada and Zegna provide on their website an opportunity for consumers to rate their products and share any experience through their preferred social media platforms. According to Kapferer (2014), this strategy enables the brands to enhance information sharing and dissemination of good testimonials to a wider audience, since a majority of their consumers are present in multiple social media platforms.

Luxury brands prefer to link their online platforms for several reasons. Firstly, according to Verhoef et al (2017), it is meant to integrate all the platforms so that the consumer does not feel like there are in a separate ‘world’. For that reason, Gucci for example, links its website to its Facebook, Instagram, twitter and e-commerce platforms. The brands have also gone a notch higher by providing QR codes on most products to enable consumers’ access to instant information (Saunders et al 2012).

Hence, a conclusion can be made that luxury brands use strategies such as providing links to other online platforms (social media) on their primary platforms (website) to ensure that they interact with consumers on different channels. Likewise, providing consumers with options to share testimonials and useful information to other social media platforms is a strategy used by luxury brands to present their ranges and image online.

Brand website being the primary platform for customer interaction among luxury brands, we conducted a subjective analysis of the customer experience created by these websites and compared them across several luxury brands including Gucci, Burberry, Prada, and Zegna. Of focus were the website functionality, branding, content, and usability. The analysis was purely subjective and may not be as accurate, reliable and valid as would be in a formal research (see appendix 2). All the compared brands appeared to be having satisfactory content, with Gucci and Burberry having an excellent presentation of content. This was as observed in their typography and the attractive nature of the wording. The messaging was also clear and easy to understand. Furthermore, the usability, functionality, branding and the general experience of interacting with the websites were above average with Gucci having the most superior general experience. Hence, through the observation, it can be concluded that luxury brands have mastered the art of constantly improving their websites especially in recognition of the fact that the websites are the first online platforms visited by consumers when they are looking for an online interaction.

Likewise, as illustrated in appendix 3 to explore different luxury brands and how they compare with regards to omnichannel retail, we examined a set of data that was collected online. This data compared different luxury brands on how they interact with consumers online especially with regards to the kind of online touch points they have and their level of cross-channel integration. Majorly, only Gucci, Prada, Burberry and Zegna were compared because their data were readily available. This data revealed that all the four brands had a website, with Burberry, Prada, and Gucci having a link on their website directing the consumers into its social media platforms. Similarly, all the four brands had a presence in at least 6 social media platforms while cross-channel integration appeared to be high in Gucci, Prada, and Burberry and low in the case of Zegna. This indicates that most luxury brands are present in major online platforms and use these platforms to present their range and image to consumers.

Limitations and Recommendations for Further Research

A major limitation faced during the survey is that it was difficult to change the method of administration whenever necessary due to the inflexible nature of surveys (Saunders et al 2012). However, this challenge was turned into an opportunity following the fairness and preciseness nature of surveys. Similarly, it was a challenge to ask the customers some controversial questions, for example how they could compare their experience with Gucci and other luxury brands. According to Verhoef et al (2017), this is because it is difficult to establish the truth behind such controversies especially through face to face interviews. Lastly, would like to make a recommendation for future study on how ordinary brands (non-luxury brands) present their image and range online since this study only concentrated on luxury brands.

References

Ailawadi, K, & Farris, P 2017, 'Managing Multi- and Omni-Channel Distribution: Metrics and Research Directions', Journal Of Retailing, 93, The Future of Retailing, pp. 120-135.

Baker, J, Ashill, N, Amer, N, & Diab, E 2018, 'The internet dilemma: An exploratory study of luxury firms’ usage of internet-based technologies', Journal Of Retailing And Consumer Services, 41, pp. 37-47.

Balakrishnan, J, Cheng, C, Wong, K, & Woo, K 2018, 'Product recommendation algorithms in the age of omnichannel retailing – An intuitive clustering approach', Computers & Industrial Engineering, 115, pp. 459-470.

Berman, B 2016, 'Planning and implementing effective mobile marketing programs', Business Horizons, 59, pp. 431-439.

Blom, A, Lange, F, & Hess, J 2017, 'Omnichannel-based promotions’ effects on purchase behavior and brand image', Journal Of Retailing And Consumer Services, 39, pp. 286-295.

Belu, M, & Marinoiu, A 2014, 'A NEW DISTRIBUTION STRATEGY: THE OMNICHANNEL STRATEGY', Romanian Economic Journal, 17, 52, p. 117.

BRYNJOLFSSON, E, YU JEFFREY, H, & RAHMAN, M 2013, 'Competing in the Age of Omnichannel Retailing', MIT Sloan Management Review, 54, 4, pp. 23-29.

Bryman, A. & Bell, E (2015) Business research Methods. 4th edn. Oxford University press.

Chatterjee, P, & Kumar, A 2017, 'Consumer willingness to pay across retail channels', Journal Of Retailing And Consumer Services, 34, pp. 264-270.

Faulds, D, Mangold, W, Raju, P, & Valsalan, S 2017, 'The mobile shopping revolution: Redefining the consumer decision process', Business Horizons.

Grewal, D, Roggeveen, A, & Nordfält, J 2016, 'Roles of retailer tactics and customer-specific factors in shopper marketing: Substantive, methodological, and conceptual issues', Journal Of Business Research, 69, pp. 1009-1013.

Gerrikagoitia, J, Castander, I, Rebón, F, & Alzua-Sorzabal, A 2015, 'New Trends of Intelligent E-marketing Based on Web Mining for E-shops', Procedia - Social And Behavioral Sciences, 175, Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Strategic Innovative Marketing (IC-SIM 2014), pp. 75-83.

Inman, J, & Nikolova, H 2017, 'Shopper-Facing Retail Technology: A Retailer Adoption Decision Framework Incorporating Shopper Attitudes and Privacy Concerns', Journal Of Retailing, 93, The Future of Retailing, pp. 7-28.

Kapferer, J 2014, 'The future of luxury: Challenges and opportunities', Journal Of Brand Management, 21, 9, p. 716.

Li, Y, Liu, H, Lim, E, Goh, J, Yang, F, & Lee, M 2017, 'Customer's reaction to cross-channel integration in omnichannel retailing: The mediating roles of retailer uncertainty, identity attractiveness, and switching costs', Decision Support Systems.

McCormick, H, Cartwright, J, Perry, P, Barnes, L, Lynch, S, & Ball, G 2014, 'Fashion retailing – past, present and future', Textile Progress, 46, 3, p. 227.

Molla-Descals, A, Frasquet, M, Ruiz-Molina, M, & Navarro-Sanchez, E 2014, 'Determinants of website traffic: the case of European fashion apparel retailers', International Review Of Retail, Distribution & Consumer Research, 24, 4, p. 411.

Oberoi, P, Patel, C, & Haon, C 2017, 'Technology sourcing for website personalization and social media marketing: A study of e-retailing industry', Journal Of Business Research, 80, pp. 10-23.

Pallant, J. (2010) SPSS Survival manual. 4th edition. Maidenhead. McGraw Hill.

Rodriguez-Torrico, P, Cabezudo, R, & San-Martin, S 2017, 'Tell me what they are like and I will tell you where they buy. An analysis of omnichannel consumer behavior', Computers In Human Behavior, p. 465.

Saunders, M., Thomhill, A., & Lewis, P. (2012) Research Methods for Business Studies. 6th edn Harlow: Financial Times/Prentice Hall.

Sebald, A, & Jacob, F 2018, 'Help welcome or not: Understanding consumer shopping motivation in curated fashion retailing', Journal Of Retailing And Consumer Services, 40, pp. 188-203.

Taufique Hossain, T, Akter, S, Kattiyapornpong, U, & Wamba, S 2017, 'The Impact of Integration Quality on Customer Equity in Data Driven Omnichannel Services Marketing', Procedia Computer Science, 121, CENTERIS 2017 - International Conference on ENTERprise Information Systems / ProjMAN 2017 - International Conference on Project MANagement / HCist 2017 - International Conference on Health and Social Care Information Systems and Technologies, CENTERIS/ProjMAN/HCist 2017, pp. 784-790.

Verhoef, P, Stephen, A, Kannan, P, Luo, X, Abhishek, V, Andrews, M, Bart, Y, Datta, H, Fong, N, Hoffman, D, Hu, M, Novak, T, Rand, W, & Zhang, Y 2017, 'Consumer Connectivity in a Complex, Technology-enabled, and Mobile-oriented World with Smart Products', Journal Of Interactive Marketing, 40, pp. 1-8.

Willems, K, Smolders, A, Brengman, M, Luyten, K, & Schöning, J 2017, 'The path-to-purchase is paved with digital opportunities: An inventory of shopper-oriented retail technologies', Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 124, pp. 228-242.

Continue your journey with our comprehensive guide to The Impact of Gender and Personality Traits on Inhibitory Control in Adolescents.

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts