Challenges Facing Makoko Fishing Communities

Introduction

Primary producers make up one quarter of the world's poorest people, most of whom engage in subsistence agricultural production and have limited access to larger markets. For these poor producers, in this case individuals who live below $2 per day, creating access to markets, organisations and ecosystems is imperative in creating a business model that adds substantial value to their current operations. In Lagos state, Makoko is one of the cities with the largest fishing communities. The ‘venice of Lagos’ a term coined by reporters is a rural slum located along the Third mainland bridge. It is made up of six different villages spread across land and water: Oko Agbon, Adogbo, Migbewhe, Yanshiwhe, Sogunro and Apollo. The first four are the floating communities, known as “Makoko on water”. The area is inhabited by over 100,000 people from Benin republic, Togo and Badagry. The Makoko community, is widely known for extremely poor living conditions and a high rate of poverty. It is estimated that more than half of the population lives on less than $1.25 per day. Despite the challenges, the community is able to capitalise on its surroundings by adopting fishing as the main economic activity. Artisanal fisheries are the main mode of production in the settlement. Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) defines artisanal fisheries as the ‘’traditional fisheries involving fishing households (as opposed to commercial companies), using relatively small amount of capital and energy, relatively small fishing vessels (if any), making short fishing trips, close to shore, mainly for local consumption’’. In Makoko, fish is sourced inland using locally made canoes with small engines. The women in the community (wives of the fishermen) are responsible for selling, and are required to sell all the fish on the same day due to inadequate options for storage that is attributed to the lack of electricity. Therefore, the aim of the paper is to:

Problem statement: Create a sustainable new business for Makoko Fishermen that addresses the lack of storage facilities for fresh fish and creates access to wider markets within Lagos city. Makoko Direct, a cold van will transport, store and sell fresh fish in urban domestic market, specifically upmarket neighbourhoods. The initiative will also partner with local NGOs to provide training on business and packaging skills. The business will provide a cost-effective, environmentally friendly and sustainable solution to the problem. Enabling access to consumers with higher incomes, will primarily increase revenue and ultimately improve the livelihoods of fishermen in the community. Also, providing training will provide education on how to capture more value from produce.

The area was selected due to its location in the heart of Lagos, Nigeria’s financial hub. Its location, depicts the large income inequality gap characterised by many developing countries. Partridge (1997) states that restricted access to credit, political instability and education as the main reasons for income inequality within poor countries. Makoko is located under the Third mainland bridge that separates Lagos island and the mainland. Its close proximity to upscale neighborhoods such as Ikoyi, victoria island and Lekki, makes potential for growth in the area feasible, if access to these markets is created. The paper will be divided into four parts: (i) The literature review will explore the problems faced by producers at the bottom of the pyramid (Bop) and the concept of value for the BoP segment, (ii) Research and methodology highlights the approach used in data collection, (iii) Data analysis shall evaluate each method of data collection and provide an analysis of each theoretical framework used to develop the BMI, (iv) Recommendation examines the proposed business model innovation.

Literature Review

Focusing on the creation of value within the supply chain of Makoko fish supply to consumers in nearby markets, the literature review will explore the concepts of value creation and production at the bottom of the pyramid. These concepts should help shed some light on how to improve the current mode of supply and provide insight on business and marketing tools that apply specifically to producers at the bottom of the pyramid such as the Makoko Fishermen.

Producers at the bottom of the pyramid

Prahlad & Hart (2014) define the bottom of the pyramid (BoP) as Tier 4 consumers with an annual income of less than $1500. The seminal book, The Fortune at the bottom of the pyramid argues that Bop consumers are a ‘value conscious segment’, with high demand for quality products offered by multinational companies. Through a combination of social goals with profitability, the idea of the ‘poor as consumers’ became a popular construct amongst MNC. The problem with this view is it creates low entrepreneurial expectations from the BoP population. Karani (2017) identified this problem by arguing the segment be seen as potential entrepreneurs that could improve their economic situations by increasing their level of income. However, improving income levels has proved difficult. Data shows, 60% of BoP population are employed in the primary sector and earn less than $2 a day. London et al (2009), points out two broad constraints faced by BoP producers; production and transactional constraints. Production constraints is defined as ‘producers ability to access affordable and high quality raw materials, financial and production resources’. Whilst transactional constraints concern producers ability to access the marketplace, assert market power and obtain and secure transactions’. Although the paper provides a starting point for understanding the problems faced by Bop producers, contextual causes to challenges were not explored. Going beyond constraints of BoP producers, Banerjee and Duflo (2007) empirical paper, provides insight into the causes of poverty. The work, draws on data from 13 countries, to explain how the poor live their lives. Causation is linked to the operation of the poor in informal markets and the inability to turn dead assets into capital. The literature highlights the importance of understanding the cause of the constraints when creating a social business model. Yunus et al (2009) explains, business models that focus on stakeholders as opposed to shareholders ‘are more tailored to addressing overwhelming global concerns’. In line with the literature, interview questions focused on understanding the causes of poverty among Makoko fishermen (BoP producers). To this end a viable business model central to the challenges faced, was developed to ensure social value maximisation.

Value creation at the Bottom of the pyramid:

Continue your exploration of The Potential and Challenges of Passenger Drones in Airports with our related content.

Value can be defined from two perspectives, consumer and producer value. Keith (1960) states, value is realised for consumers, when they receive the best price for a good or service. Holbrook (1994), expands the definition of value, to include the trade-off between the cost and benefit associated with a product. Both definitions highlight the subjectivity in defining value, as consumers will assign value, based on individual trade off analysis or what they think is ‘best’. This analysis however, only comes to play when determining value-in use as opposed to the value in exchange of a service or product. Value-in-use, is defined as the consumer's willingness to pay for a good in relation to their wants and needs. Lal Dey et al (2015) explains that consumers wants and needs depend on perceptions, ability, skills, knowledge and is perceived by their interaction with various stakeholders or while consuming the product. Whilst value in exchange is ascertained at the point of sale, and is the monetary value assigned to the given entity. Although economics and marketing literature provides a good analysis of consumer value, research fails to highlight the weight consumers ascribe to value in exchange and in use. However, the literature is clear on the fact that utility and costs are vital concepts when determining consumer value. For producers, Lindgreen (2011) explains value to mean, ‘the minimum monetary cost to purchase or manufacture a product to create appropriate use and esteem values’. In other words, producers attain value when the exchange value (value-in exchange), is higher than the total cost of resources invested. This definition is in line with entrepreneurship literature, which places profit maximisation as the primary goal of commercial entrepreneurs. For BoP consumers and producers value is reviewed in a different context. Literature is very focused on ‘how to create value’ as opposed to the ‘meaning of value’. London et al (2009), explains that the realisation of value is only attained when there is collaboration between ventures operating in this sector and the BoP segment they are helping. The authors, assert that it is only through mutual value creation that Bop needs are met. In contrast to traditional literature on value, BoP literature denotes consumer value as providing for needs as opposed to wants. The existence of negative externalities caused by institutional voids in these markets means basic services such as clean water, electricity are not provided. Randan et al (2011) suggests that by simply addressing these needs, value is created for consumers at the BoP. Most of the literature on value creation in BoP market classify the segment as consumers and therefore excludes producers in their analysis. However, Randan et al (2011) provides insight into the creation of value for BoP producers. The authors suggest, that by involving BoP producers as ‘co producers’ in business model value is created through the additional income and skills provided.

Business Models at the Bottom of the Pyramid

King and Lynghjem (2016), presented a thesis concerning the categories of business models that are adopted in the bottom of the pyramid segment in South Africa. The business model categories which were developed by the authors include the Poverty Premium Eradication, Multipurpose Product, and Engaging the Entrepreneurs categories, of which they believe they provide a systematic insight to the way value can be created for BoP consumers. The study also identifies that the delivery of value to customers is an aspect that is separate from the business model category (Henrik and Lynghjem 2016). The ability to provide a solution to a particular problem, according to the study, depends on the quality and integrity of the business model framework. The category of engaging the entrepreneurs is founded on the idea of integrating the BoP in a value chain while giving them income, and providing end-products or services to final consumers at lower prices. Offering the BoP income in this category sets them in the position of being suppliers of raw materials. The category of poverty premium eradication involves the removal of premiums which, due to being part of the informal economy, are imposed on them. This premium alleviation is done by the inclusion of customers from the formal economy in the business model. Through providing the formal economy customers with services and goods, the poverty premium is eliminated and value is created for every involved party. The category of Multipurpose Category involves the approach to the BoP consumers using products consisting of more than one feature. The costliness arising due to increased features on a product is an identified problem in this category and it is overcome by the increased willingness to buy among the BoP consumers (Henrik and Lynghjem 2016). The end-result following the implementation of these business models, as incorporated by a variety of MNCs, is that it provides basic goods to the poor at prices which they can easily afford and which attract acceptable interest to the owners.

Issues Concerning Food Distribution

A study by Nordmark (2015) reveals that local food is growing in popularity and is often associated with low impact towards the environment. Popularity reflects the consumer attitudes such that they perceive it as being environmentally friendly, natural, and good quality. The author also identified another attribute which is similar to traits of the BoP segment that local and small-scale producers have insufficient resources to optimize means of transport. One constraint in food distribution as identified by Nordmark (2015) is the need for more transparency among consumers in food supply chains. This is due to the incidence of food-bourne illnesses, genetic modification and issues with product integrity and safety. Producers in the food supply chain are faced with challenges relating to logistics, information technology, regulatory framework and quality. According to Gebresenbet & Bosona (2012), food supply chains are faced with limited infrastructure which is likely to be often inefficient and fragmented and the fraction of transport expense per unit of product is high. Mulky (2013), in his study, points out that one main challenge in managing distribution channels is keeping the members of the channel motivated, especially when the markets get tough. Different kinds of non-financial and financial incentives are used by firms to ensure that the channels have healthy returns on investment, enough to keep the channel members motivated. These incentives can include support for market development, supplemental contact, credible channel policies, end-user contact and high-powered incentives. Mulky (2013) also asserts that the level of economic development affects distribution channels. While developed nations have distribution channels characterized with large and organized wholesalers and retailers, channels in developing nations tend to have unorganized retails and wholesalers, less technology integration, an evolving structure of logistics and scanty internet penetration. What is likely to drive a change in the distribution channel is the volatile consumer needs, channel sophistication, consumer sophistication, changes in environment such as competitor’s strategies and company sizes (Mulky 2013).

Optimum Types of Good sold in a Distribution Venture

Prior to setting up a distribution venture, it is worthy to confirm the nature of the products. Some are durable, perishable and even fragile (Szope and Pekala 2012). Also, the preferred method of transfer of goods in a distribution channel depends on the expected utility of the end-product regardless of the quality of design of that product. This forces organizations to select distribution methods which are able to deliver goods to end-users at the right place and right time (Fayaz and Azizinia 2016). The types of goods sold in a distribution venture depend on consumer’s income and preferences. When consumer income is high, certain types of good acquire high demand while others are in low demand (Amadeo 2019). This affects the characteristics of goods in a distribution venture. Also, when a consumer segment is in favour of certain goods, they will make up the largest portion of the goods transported by a distributing agency. With this ideology, distributing ventures are likely to set up shop in market places where the products and services in circulation are of high demand as this will have a positive impact on their profitability (Amadeo 2019). Considering the goal of this study, of developing a business model and marketing strategy that will facilitate the movement of goods, it is relevant to lay focus on consumer goods. There exist different kinds of consumer goods (Chappelow 2019). These include specialty products, shopping goods, convenience goods and fast-moving consumer goods. In particular, fast moving consumer goods, such as drinks and food, have a high average demand in comparison to other types of goods (Deloitte 2017). Therefore, distribution channels are flocked with fast-moving consumer goods because of their characteristics of being non-durable, having a high velocity in the market such that they move fastest in the distribution chain from the producers, distributors, retailers and ends with the consumer.

Research and methodology

Investigation was carried out over the course of five days. The first three days focused on accessing information from Makoko community. Day two and three were spent observing purchase behaviour in two the largest supermarkets in Lagos. One major limitation to the data collection was the use of a translator during the Makoko interviews. It was evident that more was being said than what was getting translated, leading to omission and reduction of content. To address this limitation, observation was used to fill the gaps.

Research design

To better understand the challenges faced by the fishing community in Makoko, an inductive approach to data collection was conducted. Hussein (2019), finds that using an inductive approach, fosters creativity and provides a systematic analysis of data collection. In this paper, a single case study was used as the premise for developing the business model. Adopting this method, provided in-depth knowledge of the social, cultural and institutional problems faced by the community. According to Simanis and Hart, the single case study approach, encourages the development of a model that adapts to the local context and builds on local conditions. This reduces the possibility of creating a ‘one size fits’ approach and ensures the development of a viable and sustainable business model.

Desk Research

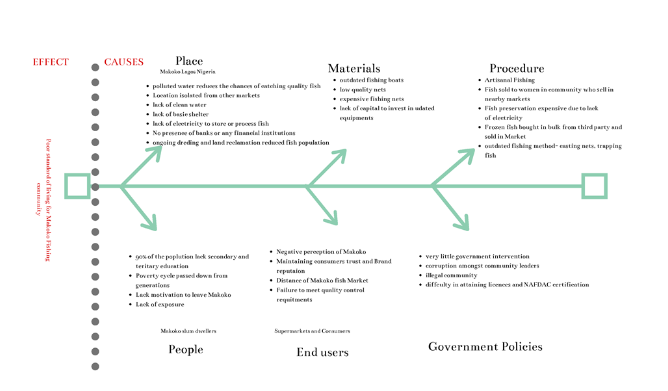

In order to determine the area of investigation and research questions, desk research was conducted. Literature specific to primary producers in developing countries, production at the bottom of the pyramid and mutual value creation were all examined. General information, on fish production in Nigeria, inequality rate and income disparity were also explored and informed the survey questions. Key consumer segment in the proposed business model was selected based on literature which identified areas with the highest living wages as Lekki and Ikoyi (see Figure 1). The Ishikawa diagram was also used to identify the main causes of poverty amongst Makoko fishermen. The procedure involved:

1. Establishing identifying the main effects

2. Brainstorming sessions was held to identify the causation

3. To identify causation, ach identified cause was broken down, by asking ‘why’.

4. Finally, the main reasons behind the causes, were identified and arranged on a flip chart diagram.

The diagram, provided a better understanding of the root causes of the difficulties faced by the fishermen. Differentiating between major and minor problems was also made easy. However, the diagram only provides a framework for analysis and does not provide evidential data.

In-depth Interview with MAKOKO Residence

The second step to the methodological approach was in depth interviews with residence of Makoko. Two semi-structured interviews were conducted with a female fish seller and a young fisherman. A group interview with five more experienced fishermen was also conducted. Interviews were coded and a thematic analysis was conducted. The face-to-face interviews were useful in understanding expenditure patterns of fishermen, which helped inform the savings pathway proposed as part of the business model. Respondents were selected based on the level of information they could provide on the subject matter. As Brinkman (2013) explains, the goal of information oriented selection is to maximise the utility of information from small samples and single cases. A limitation of this approach, is the exclusion of some segments in the community, who might have provided relevant information. Polit and Beck (2013) also state limited generalization as a disadvantage of this approach. They express concerns about drawing broad conclusions from instances irrelevant to the unobserved based on the observed.

Focus groups

To ‘probe the generation of new ideas’ and collect detailed information in a limited amount of time, two focus groups were held on the second visit. The session was conducted with two homogeneous groups- the members of the Fishing Association of Makoko, who were all men and fish sellers who were all women. Focus groups were held one after the other in different locations. The aim of the sessions was to identify the role of each group in fish production and sale. For example, men were asked predominantly about fishing methods and how profits from current fish production was spent. Whilst the female focus group focused on sale and packaging of product ( see Appendix 1).

Survey

A digital survey developed with Survey Monkey was used to identify potential target market for Makoko Direct. The aim of the survey was to: analyse consumer purchasing pattern, examine consumer attitudes and willingness to pay for social services in upmarket neighbourhoods. Respondents were selected using snowball sampling. Snowballing, takes advantage of the social networks of identified respondents to provide a researcher with an ever-expanding set of potential contacts (Thomson, 1997). The survey included eighteen questions, with a mix of multiple choice questions, Likert scale and single entry prompts style questions to address gaps in the survey.

Observation

Observation was used to identify non-verbal cues expressed during the interview. For example, on observation, the research found that participants were not comfortable with ‘outsiders’ in the community. This was as a result of lack of trust caused by unfulfilled promises made by visitors to the area. What was particularly interesting, was the ongoing construction of High Rise flats beside the slum (See figure), the presence of which buttresses the point on the inequality gap in Lagos.

Data analysis

Ishikawa diagram

Place, material, procedure, people, end users and government policies were identified as generic themes. The head of the diagram identifies the main effect as: Poor standards of living in Makoko fishing community. Arrows point to the underlying causes of the effect. For example under materials; outdated fishing boat, low quality net, cost of fishing nets and lack of capital to invest in updated equipment were all identified as major reasons for the poor standard of living for fishermen in Makoko. Some causes are also interrelated, an example can be seen under the Material and Procedure hoc both have ‘outdated fishing methods’ as a cause in Fig.

Demographic analysis

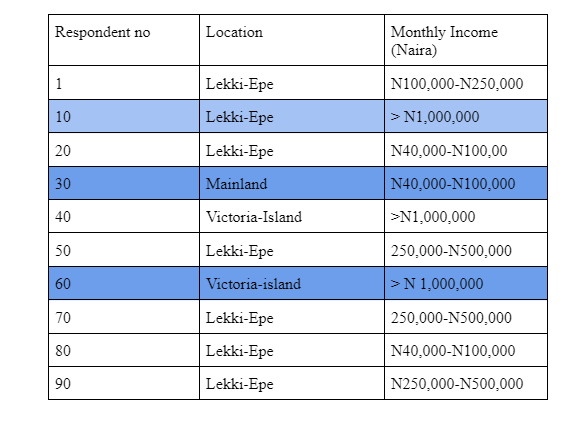

The survey received 132 responses, with a completion rate 100% and an average time spent was 4 minutes per response. More than half of the respondents were women, with only 22% of men participating in the survey. Respondents were primarily aged between 18-55. Lekki-epe axis, Mainland and Island were identified as the top three locations for most respondents. There were a few anomalies as some people resided outside the country. Lekki-Epe had the highest responses with 46%, compared to 27% responses from Victoria Island. To establish the link between demographic and income, individual responses were analysed. The data shows, respondents who live on the Lekki-epe axis received a monthly income between N100,000 ( $275.28) to N1,000,000 ($2,752). The gap between income levels can be linked to the wide geographic area covered by Lekki-epe axis. Moreover, age and skill set of each individual might also be responsible for the results. Out of the 26.92% of the respondents on the mainland 16% earned a monthly income below N250,000 ($688). In contrast, 90% of the 17.6% respondents from Victoria Island and Ikoyi earned over N1,000,000. Data from every 10th respondent comparing location and monthly income can be seen in Table ( ). The table below provides a clearer picture of the analysis provided.

Product analysis

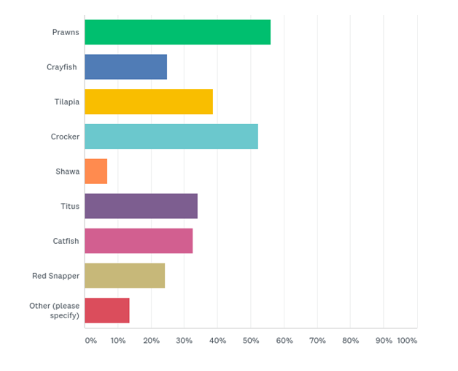

Fig () shows, prawns, crayfish, tilapia, crock, catfish and titus as potential product offerings. Prawns in particular appeared to have the highest demand, despite being the most expensive ( see Appendix)

Consumers attitudes

Seven independent variables were analysed to understand value drivers for consumers. 79% of respondents attributed quality to fresh fish. Price and packaging were also identified as the two most important factors in consumers purchasing decision for fresh fish. Although, 80% of respondents considered themselves ‘source conscious’ only 11.45% source fish locally. Respondents identified health and ‘love for seafood’ as primary reason for fish consumption. Costs only accounted for 6% of responses, indicating consumer purchase mainly driven by hedonic reasons. 80% expressed some degree of interest in purchasing fish from Makoko, however over 50% were, only willing to pay the minimum price (N200-N500). Results can be seen in Figure( )

Thematic analysis

In a country like Nigeria, ( state problems) (state how not suprsing) From the thematic analysis, codes were identified and organised into basic and organising themes. Identified codes from the thematic analysis ( ) correlate with the BoP constraints framework developed by London (2009). For example, fishermen expressed concerns over ‘cost of machinery needed to make fishing nets’,and ‘the ‘cost of buying nets’. Complaints regarding the ‘lack of electricity’ which contributed to higher costs as producers had to purchase ‘packs of ice block’ to store produce. Some reported using old clothes as a means of keeping fish cold. It was also clear that respondents lacked technical know-how needed to improve production input as the most urgent challenges identified were ‘more fishing nets’ and ‘sunroof to cover canoe’. Factors identified are described within the BoP constraints framework as productivity constraints which hamper value creation within BoP production. Furthermore, issues relating to transactional constraints were identified. For example, sale of fish was limited to ‘Sango’, ‘Iyanopanja’ and ‘Badagry’ which are geographic areas around Makoko. Also, fish sellers, ‘lacked the understanding of customers expectations in product design’. For instance, respondents (a women's focus group) reported ‘displaying fish on wooden tables’ as a form of packaging. The information asymmetry that exists can be ascribed to the inability of fishermen to access non-local markets. Lack of access to financial services also explained the lack structure savings scheme in the area, as the process was conducted by ‘weekly money collectors.’ In general, the thematic analysis, was useful in identifying, access to non-local markets, storage facilities and income generation as value drivers for Makoko Directs business model. These value drives formed the basis for the theory of change as shown in Fig (1) sections of

Business Model Innovation- Makoko Direct

Value Proposition

According to Johnson, Christensen and Kagermann (2016), a customer value proposition is the model that helps customers perform a specific function or job which is not being offered by alternative means of addressing the problem. Olofosson and Farr (2006) refer to it as the product which is introduced to the market to which a customer finds value in its use. In this case, the value proposition is a business known as Makoko Direct. Makoko Direct aims to improve local fish supply chain by introducing transportation and procurement services to the existing supply chain (see). Fish produce will be transported from Makoko to markets on closer to Lekki, Victoria Island and Ikoyi, to increase consumer segment and create access to non-local markets. The business model aimed at ensuring mutual value creation by involving local producers in the design process. It also ‘adapts to’ local context by ensuring fishermen remain ‘co-producers’.

Value Chain

The value chain consists of the value creating steps. In the context of this business model, it described as the complete range of activities required in the creation of the fish transport and marketing service. To understand the value chain of Makoko Direct, the detailed procedures in each value creating steps will be evaluated.

Inbound Logistics

As soon as fish farmers in Makoko will have delivered fresh fish from the water, they shall be collected briefly for sorting in a warehouse that will be located in the same region. During the brief period, the fish shall be sorted according to size and mass before being packaged in vans.

Operations

This step involves the conversion of raw materials, the fresh fish, into finished products. During sorting, the fish will be cut into pieces which will be packaged in cans. Another portion of the fresh fish delivered will be packaged wholly. All the packaged fish will be placed in refrigerators in the warehouse before being transferred to refrigerators in the cold vans.

Outbound Logistics.

This includes the activities taken up in the distribution of the final product to the consumer Fully packed, the cold vans shall transport the frozen packaged fresh fish from Makoko Direct’s warehouse up to distribution locations in Lagos city markets.

Sales and Marketing

This value creating activity involves the plan to increase visibility and target the correct clients within the market segments. Makoko Direct shall use promotional methods of advertisements through radio, television and social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. Another significant means of promotion is the in-store experience at Makoko Direct’s designated retail outlets. The marketing staff shall consist copywriters who will design labels for fish products in a manner which creates a good image of fresh fish from Makoko. This appealing image is expected to tap into the emotion of the fish consumers in Lagos city, giving them the feeling of supporting the local fish production.

Service

This step in value creation involves setting up programs which will maintain consistent delivery of fresh fish and enhance the experience of consumers. In practical terms, this includes maintenance and repair services, customer service, refund and exchange programs. Makoko Direct shall create value through engaging in service activities previously mentioned as well as quality assurance activities which will facilitate quality during sorting and packaging of fish to ensure freshness. In the case of customer complaints regarding quality of fish, a refund program will be adopted which requires no asking of questions when making refunds to customers. However, a time-limit shall be integrated in the implementation of the no-questions-asked refund program. A lenient policy of refund, such as one to be adopted by Makoko Direct will induce more returns and an increase in purchase of fresh fish.

The Use of the 4A’s

Awareness

The BoP stakeholders ought to be informed of the services being offered by Makoko Direct. According to van der Klein, Mancheronm Wertheim and Collee (2012), the creation of awareness is difficult due to the existence of media-dark zones. Makoko is a media-dark zone which consists a high level of illiterate individuals who are also from minority language groups. To facilitate awareness of the business among the fish farmers in Makoko, word of mouth shall be relied upon, whereby people shall rely on information from people who they trust and are familiar with.

Acceptability

In order to understand the acceptability of Makoko Direct, it is crucial that the existing behaviour as well as the magnitude of changes will be accepted to allow the people of Makoko to enjoy the benefit of having a cold van transporting fish in frozen state to markets in Lagos. For example, since people in Makoko suffer insufficient storage facilities due to poor electrical resources, Makoko Direct will be found as a worthy business, a lucrative means of tapping into the affluent market and increasing number of fish acquired for the day.

Affordability

People in the BoP are unable to afford luxury or costly services and resort to living their lives with few resources which causes them to make sacrifices and balance their investments smartly all at the same time (van der Klein, et al. 2012). Affordability is crucial in Makoko Direct’s value chain because it is vital to consider that the beliefs and perceived benefit held among actors in the BoP of the solution being provided could cause them to make more investments which they could easily trade off with another investment. For instance, instead of relying on the cold vans to transport fresh fish, the Makoko residents could Makoko Direct as offering expensive services and a trade-off could be done by resorting to displaying fish on wooden tables.

Accessibility/ Availability

For the BoP producer base to be fully satisfied, there needs to be an uninterrupted uptake of fish products. This will be a challenge, especially in Makoko where there is limited established logistical infrastructure. This is similar to Mpesa, a mobile-banking business in Kenya where kiosks branded Mpesa are present in BoP markets (villages and slums) which are managed by an individual from the community (van der Klein, et al. 2012).

Key Activities

Csadesus-Masanell (2015), asserts that an organization requires key activities in order to ensure consistent flow and operability of the business model. The key activities of Makoko Direct shall arise from the problem that is being solved – the need to create access to the wider markets within Lagos city. The key activities are discussed as follows;

Transport

Makoko Direct shall connect the fishermen of Makoko the affluent market in Lagos city using a cold van. The cold van will be fitted with refrigeration equipment which will attempt to freeze the fish using air-blast freezing technique, where air that is roughly -30°C gets blown at high velocity over the fish stacked on pallets for forklifting. According to Tassou, De-Lille, and Lewis (2007), refrigeration in road transport is necessary for the reliable operation in harsh environments. One constraint that is identified with the use of a cold van is the limitations brought about by weight and space of the food (fish) that is being refrigerated. This constraint will be overcome by using more than one cold van to ensure that more fish is transported from the producers to the upmarket in Lagos.

Marketing

Makoko Direct shall perform the acitivity of marketing fish products from the local Makoko fishermen to the target market in Lagos city. Marketing will address the transactional constraint faced by the BoP producers in Makoko giving them a voice by being able to access the market place and assert their market power. The marketing activities shall be congruent with the marketing strategy for Makoko Direct. In brief, the marketing strategy will focus on fulfilling the Lagos city customers’ need for fresh fish at affordable price. The main method of promotion that will be used will be through radio and television advertisements as well as social media platforms such as WhatsApp and text messages.

Key Resources

Financial Resources

To begin Makoko Direct, capital shall be sourced through traditional means of financing. This is particularly through a bank loan that will cater for the purchase of vans and having them specialized by fitting them with cooling compartments. The cold vans shall also serve as the source of accounts receivables as they will be used in performing the main function of the business – transport. The already existing vans can be used to acquire finance using title loans as well. According to the value of the existing cold vans, a loan can be acquired from the bank while using them as the collateral. This will facilitate the expansion of the business by expanding the number of cold vans in possession.

Physical Resources

The physical resources shall consist the fixed assets that will be owned by Makoko Direct business. These shall include the cold vans which will be purchased to facilitate the transportation of fish, the physical retail stores in the Lagos city markets, a warehouse consisting refrigerators which will be used to store fish and an office building.

Human Resources

The human capital who will be directly involved in the day-to-day operations of the business include drivers and marketing research and development, and specialists teams. Other members of the company’s staff shall include a chief accountant, a managing director, a head of marketing department and distribution department. the Accounting, marketing and distribution operations department shall consist of two departmental members who will be responsible of running of daily operations as per their job specifications. Human resources shall be outsourced for the non-key activities to be performed by the organization. For instance, human resource can be sourced from a LG company, such as engineers who will accomplish the task of retrofitting the vans with refrigeration technology and carry out periodical inspection for quality purposes.

Intellectual property

The intellectual property that will be part of Makoko Direct is a website, established for the purpose of reaching out to clients and suppliers using the internet. Another valuable intellectual property which the organization shall adopt is the development of specialized programs from an external software programming company. It will be agreed that since the organization owns the idea for customization, the software program shall be considered as the intellectual property owned by Makoko Direct.

Cost Structure

Considering the nature of the business, several costs are brought forward. These include costs of fuel, promotion, repair and maintenance of the cold vans, sourcing for experts and payment to fish suppliers from Makoko. The fuel costs will arise from the to and from movements of the cold vans between Makoko and various marketplaces in Lagos city, specifically Lekki and Oniru market. Promotional costs shall arise from the need to advertise on the various preferred channels of communication, such as radio, television, and social media applications. The costs involved in the repair and maintenance of the cold van shall include all expenses directed towards buying spare parts, replacements and making adjustments in the vehicles. Costs associated with sourcing for experts will include those incurred when paying engineer, fish retailers, marketing professionals and other types of human capital that is either directly or indirectly related to the business.

Revenue Stream

Makoko Direct shall earn money from profits acquired from its key activities; transporting and marketing. Makoko fishermen who will be part of the registered and verified suppliers of fish to the business shall pay an enrollment fee that is paid on a monthly basis. Retail outlets, to whom Makoko Direct will have transported fish, will also pay enrollment fees for fish deliveries. Revenue will also be collected from retail outlets set up by Makoko Direct from which fish will be sold directly to consumers in the Lekki and Victoria Island region. Accounts receivables from enrollment fees will be channeled towards investments in marketing activities and the marketing department. The marketing investment expenses shall be offset by the revenue collected from retail outlets and enrollment fees.

Partners

Following the listing and description of key tasks to be accomplished by Makoko Direct, there remain activities which are of great significance for the operation of the company which will not be done by the company itself. These are the non-key activities which will be acquired from the partners to Makoko Direct. To facilitate the transport activity, Kojo Motors Ltd. will be approved supplier of vans manufactured by Toyota . Kojo Motors Ltd. will also provide engineers and mechanics who will be in charge of random inspection and maintenance of the vehicles after particular mileages. Makoko Direct will partner with Makoko Fishermen who are the local producers and suppliers of fresh fish. Makoko Direct will also partner with retailers who will have enrolled for the transport service offered by the firm to have fresh fish delivered in their stores. For financial institution which will partner with the organization for the purpose of acquiring credit obligations will be National Agricultural Co-operative Bank (NACB).

Bibliography

Casadesus-Masanell, Ramon, and John Heilbron. The Business Model: Nature and Benefits. PhD Thesis, Harvard Business School, 2015.

Johnson, Mark, Clayton Christensen, and Henning Kagermann. "Reinventing Your Business Model." Harvard Business Review (Harvard Business Press), 2009.

Olofosson, Lotta, and Richard Farr. "Business Model Tools and Definition - A Literature Review." VIVACE Consortium Members (ResearchGate), 2006.

Tassou, S A, G De-Lille, and J Lewis. Food Transport Refrigeration. SemanticScholar, 2007.

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts