Understanding Domestic Violence Withdrawal

Introduction

Domestic violence is a crime. It is also a social problem, which victimises a significant number of women every year. Laws enacted to respond to the crime of domestic violence include the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012, which also provides the statutory definition of domestic violence, and the Serious Crime Act 2015, and the Protection from Harassment Act 1997. These legislations are aimed at defining the crime of domestic violence as well as providing criminal measures against this crime. Despite these measures, research indicates that there is a problem of case withdrawal by victims of domestic violence, and that this issue affects women from the African communities in specific ways due to cultural and social reasons (Izzidien, 2008). However, as of yet there is no significant research that reveals and reflects on the factors responsible for case withdrawal in domestic violence cases. The principal research question that this study posed was “what are the reasons for case withdrawal of criminal complaints against the perpetrators of domestic violence in black communities?” The research question is structured to delimit this study to the victims of the Black communities and to only explore the reasons why these victims withdraw their complaints from the criminal justice system. Therefore, this research study will not be considering any other communities for this study keeping the focus on the women from Black communities only. The purpose of this delimitation is to ensure that the research remains focussed and only the relevant literature is identified based on the exclusion and inclusion criteria, which is derived also from the research question posed in this study. This study is an exploratory study which seeks to collate the available literature on case withdrawal in criminal cases involving domestic violence. The study is secondary in nature with a focus on the available literature on domestic violence and how this literature explores the factors related to case withdrawal in domestic violence cases. The purpose of the study is to identify the factors that are identified in literature and empirical research as the factors that are responsible for making women withdraw their cases from the criminal justice system even after being victimised by their husbands or partners, and to identify the gaps in the literature if any. The following section discusses the research methodology in detail.

Research Methodology

This research has been conducted with a qualitative research design, which allows for more insightful and analytical research that can be useful for research into areas of study that are complex, such as the current research area into domestic violence (Creswell, 2013). Domestic violence is a social problem, and it has also been responded to with legal measures; the reasons why women may choose to remove their complaints from within the criminal justice system even after victimisation may be complex and multi-layered in nature. This makes the research amenable to a qualitative research design. Qualitative methods and techniques are appropriate in research designs that are related to sensitive subjects because qualitative methods are not rigid and can be modulated to suit the needs of the research and to provide a more flexible framework within which the researcher can explore opinions and experiences of participants (Creswell, 2013). Domestic violence is an area that involves sensitive information, which makes it appropriate for a qualitative design in research. The qualitative research method has been used in this research to gather qualitative data that relates to the reasons why the victims of domestic violence are formally and informally disengaging with the legal system. A qualitative research will be useful for this research because it will allow the researcher to use appropriate methods for collecting data that gives more insight into the reasons why victims withdraw their cases against the perpetrators of domestic violence. A quantitative method, which focusses on numerical data, would not have allowed such in depth research into an area that is complex and multi-layered due to which this design is preferred. The method chosen to collect data in this research was literature review. The literature review method was used to explore the major themes in existing research. Preliminary literature review suggested that there is literature on this area, which also includes literature and reports involving empirical research studies on the question of domestic violence. This allowed the researcher to finalise literature review method for the collection of data in this research study. The literature review method for collection of data is used to identify and collect all the existing quality literature and empirical data on the subject of research (Bettany-Saltikov, 2012). This data is in the nature of secondary data and it is collected from books, journals and reports (Bettany-Saltikov, 2012). The literature review is in the nature of a systematic review, which aims to “collate all empirical evidence that fits pre-specified eligibility criteria in order to answer a specific research question” (Green, et al., 2011, p. 6). In other words, the systematic review was conducted with the goal to locate and collate all the empirical evidence on the question of domestic violence and the withdrawal of criminal cases by the victims belonging to the Black communities. This will allow the researcher to eliminate bias by referring to all relevant literature that comes within the scope of inclusion criteria.

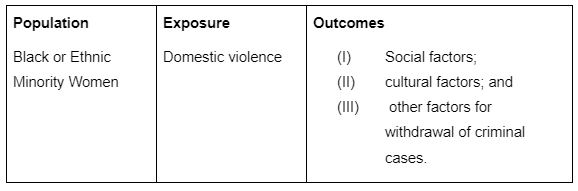

The advantage of using a systematic review method is that it helps to limit the scope of research because the researcher uses systematic methods to identify the sources of data. Because a systematic review is the summary of research literature focused on a single research question that is resultant from a process of research moving from the identification and selection of the high quality literature to the appraisal, synthesis and collation of this literature, it is possible for the researcher to conduct a credible research with the elimination of bias (Bettany-Saltikov, 2012, p. 5). Another advantage of systematic review is that even grey literature can be identified with the help of systematic review, such as PhD theses or conference papers; these grey literatures often get missed in literature review but, they can provide useful and empirical data that may be valuable to the research (Bettany-Saltikov, 2012, p. 68). In this research, attempts have been made to also identify and use such grey literatures where appropriate. Systematic review can be done by using a PEO method as advised by Bettany-Saltikov (2012) for research involving qualitative questions. The PEO method is applied by using a Population, Exposure, and Outcomes method as shown in the table below. In this research study the question is related to the reasons that cause case withdrawal of reported domestic abuse of victims in African communities. The PEO method can be applied as follows in the Table 1.1

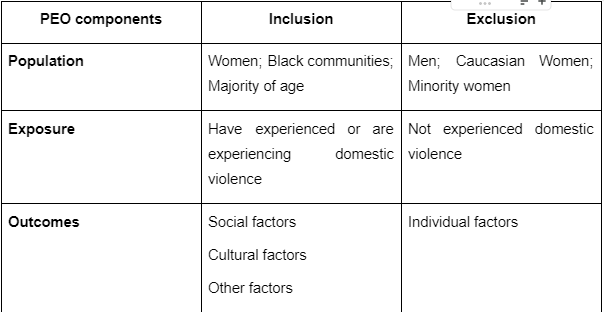

The inclusion and exclusion criteria for the application of the PEO method to the case is as follows in Table 1.2:

Based on the criteria discussed above, the systematic review was conducted, which led to the identification of the sources of literature review. The researcher used a sifting process by reading the titles and the abstracts of the sources to finally identify the sources that are the most relevant to answering the research question posed in this study. The following section of this dissertation is the literature review conducted with the sources identified in the systematic review.

Literature review

Domestic violence refers to the violence that occurs in intimate relationships, where the perpetrator is a family member or an intimate partner, who uses physical force, coercion, or other forms of abuse against the victim; it leads to harm to the physical and psychological wellbeing of the victim (Han Almis, et al, 2018). The definition of domestic violence provided by the UK Home Office is relevant here: “Any incident or pattern of incidents of controlling, coercive or threatening behaviour, violence or abuse between those aged 16 or over who are or have been intimate partners or family members regardless of gender or sexuality. This can encompass but is not limited to the following types of abuse: psychological, physical, sexual, financial and emotional.” (Woodhouse & Dempsey, 2016, p. 4) Therefore, according to the definition of domestic violence, it is a crime that is involves the use of coercive and threatening behaviour by one partner against the other. The crime of domestic violence is gender neutral as the Home Office does not differentiate between male and female victims of domestic violence. Domestic violence can also occur in homosexual relationships as well. However, in this research, the study is delimited to female victims of domestic violence in heterosexual relationships. This is because empirical data indicates that women in heterosexual relationships are more victimised and that domestic violence has a long lasting effect on women with their being victimised by sexual, emotional, physical, financial, or psychological abuse (Bostock, Plumpton, & Pratt, 2009). Women are at greater risk of domestic violence as suggested by empirical data which indicates high level of domestic abuses in 2014-15, with 8.2% of women reporting that they experienced domestic abuse (Woodhouse & Dempsey, 2016). In numbers, 1.3 million female and 600,000 male respondents reported to exposure to domestic violence (Woodhouse & Dempsey, 2016, p. 3). The number of female victims is undoubtedly high, although male victims are also considerable in number. Of serious note is the fact that 27.1% of women have reported to suffering domestic abuse since the age of 16 (Woodhouse & Dempsey, 2016). In Wales, the number was even higher with 11% of women reporting to exposure to domestic violence (Berry, Stanley, Radford, McCarry, & Larkins, 2014, p. 6). Women from Black Minority Ethnic and Refugee communities have even reported to poor access to authorities due to their reluctance to approach statutory agencies and report domestic violence (Berry, Stanley, Radford, McCarry, & Larkins, 2014, p. 11). This is an indication of the hesitation that women from minority communities may face with regard to approaching the authorities with information or complaints about domestic violence. It is possible that due to this hesitation, even when the victims from these communities do go to the authorities and file criminal cases against the perpetrators, they may at times make decisions to take the cases back. Therefore, one of the crucial areas of concern that is indicated in the literature is that women from Black communities have reported to experiencing reluctance in approaching the authorities when they are victimised by domestic violence. Coming back to the issue of the nature of domestic violence, such violence can take on various forms: it can be in the nature of physical force or coercion; or mental, emotional, and psychological force; or sexual violence; or financial intimidation of the victim by the perpetrator (Abramsky, et al., 2011). The last noted is also called as economic abuse and it relates to the perpetrator taking control over the financial decisions of the victim (Abramsky, et al., 2011). In general, there are two key characteristics that are common to different forms of domestic violence: first, the perpetrator and the victim of domestic violence are in a domestic or an intimate relationship; and second, the perpetrator’s actions or conduct, be these, physical, emotional, psychological, or economic, are controlling, coercive or threatening (Woodhouse & Dempsey, 2016). With reference to the second characteristic, it may be noted that the perpetrator’s behaviour is abusive if it is controlling, coercive or threatening, and that these behaviour patterns may be related to psychological, physical, sexual, or economic abuse (Woodhouse & Dempsey, 2016). Therefore, the defining characteristics of domestic violence are that there is coercion and threatening behaviour of the perpetrator against the victims. The victims may therefore feel intimidated and scared of the perpetrator or be dominated by the perpetrator in some way. When victims undergo such trauma or fear in their intimate relationships, the reasons why they do not report such crimes against themselves or withdraw complaints may be complex in nature. One point of significance in such situations may be that victims may need the support from the community or the authorities to counter the fear that is placed in them by their oppressors. Literature does indicate that women in abusive relationships may need community or family support to take action against the perpetrators of the crimes (Berry, Stanley, Radford, McCarry, & Larkins, 2014). Therefore, the reasons for women from Black communities to withdraw their cases may also be linked back to the lack of support from the community, family or authorities. This is another area of concern that is flagged in literature (Groves & Thomas, 2013).

In response to the above discussed issue of community support, in England and Wales a number of initiatives have been taken by the government, like appointment of Domestic Abuse Coordinators, Independent Domestic Violence Advisers, the application of the Domestic Violence Disclosure Scheme, and the National Training Framework for Wales (Home Office, 2016). These initiatives are taken to tackle domestic violence against women and to extend social support to women when they face such oppression and violence in their family lives. The Domestic Violence Disclosure Scheme applies to 43 police forces in England and Wales; under this scheme, victims or potential victims of domestic violence have access to a formal mechanism to enable them to make inquiries with the police about the abusive nature of the partners (Home Office, 2016). With such schemes being initiated, a question arises as to whether victims do take advantage of these options and if they do then why they may withdraw criminal cases against the perpetrators of the crime of domestic violence against them. As of this time, there is no extensive research that may answer this question. Literature does suggest that despite the schemes of the government, there are issues of case withdrawal, but the reasons for the same with reference to women from Black communities are not clarified (Berry, Stanley, Radford, McCarry, & Larkins, 2014). Literature also indicates that an answer to the above question, that is, why women withdraw cases despite schemes to support them may lie in the attitude of the police to domestic violence reports that come to them (Hayes, 2012). Literature suggests that police traditionally does not respond to domestic violence as police work, and considers reports of domestic violence as family matters that should best be left to the family to resolve (Hayes, 2012). This despite the laws that are made and other responses of the government to the crime of domestic violence. A more recent report indicates that there are still some areas of improvement in the police response to domestic violence; there is a need to identify risk and take positive action when required (HMICFRS, 2017). Two points that are noted are lack of identification of risks and lack of adequate positive action when risk is identified. In the Black communities, one of the reasons why women may not be open to reporting such behaviour to the authorities may be because of the concept of 'honour crimes', which is a common phenomenon in these communities as well as in other ethnic communities, particularly South Asian communities (Hall, 2014). This may mean that the communities are more closed and do not open to the external social control factors in matters that are seen to be central or core to the family and community (Hall, 2014). In such communities, there may be spoken or implied social norms against going to the police against the husband or partner. Combined with the fact that women may need conducive environment and community support and services in order to be encouraged to take criminal action against the perpetrator of domestic violence, it may lead to a situation wherein women are not able to take action or are forced to withdraw criminal complaints because their communities are not open to external controls against domestic violence. Communities that are patriarchal may not encourage women to access police or authorities and to take the required support and services needed to let the women take criminal action against the perpetrators of the crime. In other words, the communities themselves may not be supportive of the victims’ actions against the perpetrators due to patriarchal notions about marriage and family life.

Law related to domestic violence seeks to provide some recourse to the victims of domestic violence against the perpetrator’s actions and conduct. Under the British legal system, domestic violence has been recognised as a crime both under the common law as well as under the statutory law. In the seminal case of R v R, the House of Lords recognised domestic violence as a crime that may consist of rape, assault, and threatening behaviour by one intimate partner against the other (R v R [1991] UKHL 12, 1991). Statutory laws are also enacted to respond to the problem of domestic violence. The Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012, has provided the statutory definition of domestic violence. The Serious Crime Act 2015 defines domestic violence in Section 76 as coercive or controlling behaviour against an intimate partner. The Protection from Harassment Act 1997 treats domestic violence as harassment and provides certain remedies to the victim against an abusive partner, which can be claimed from the courts in the form of non-molestation orders, occupation orders and domestic violence protection orders (Groves & Thomas, 2013). However, one issue that is highlighted in the literature is that the availability of both civil and criminal law measures against domestic violence has led to the blurring of boundaries between the civil and criminal laws and led to incoherency in the framework of legal responses to domestic violence (Hitchings, 2006). In other words, there is a possibility that if the victims of domestic violence are not taking recourse to criminal law measures or withdrawing their complaints, a reason for the same could lie in the confusion created by the law itself. Not all laws related to domestic violence are of the nature of criminal laws; some laws are civil law responses to the problem. For instance, the Family Law Act 1996 provides civil remedies available to the victim of domestic violence; Section 42 allows victim to apply for a non-molestation order against intimate partner or spouse. Therefore, victims of domestic violence have recourse to certain remedies that do not require them to file criminal cases against the perpetrator. This is a criticism of the regime of civil law and criminal law related to the responses on domestic violence (Hitchings, 2006). It has been argued that the Parliament’s attempts to penalise the non-compliance with orders under the Family Act through the provisions of the Domestic Violence, Crime and Victims Act 2004, has led to the blurring of boundaries between the civil and criminal laws and this leads to the incoherency in the framework of legal responses to domestic violence (Hitchings, 2006). It may be argued that the incoherency in the law related to domestic violence also impacts the decision making of victims who may be confused by the different legal responses to domestic violence under the civil and criminal law. No research has been done so far to see how African and Caribbean women may be impacted by the legal framework on domestic violence in making their decisions regarding withdrawal of cases. A general criticism of the blurring of the boundaries between criminal and civil law is made by Hitchings (2006), but no specific attempt is made to relate this to the women in the Black communities.

Literature clearly suggests that there is a tendency amongst victims from African and some minority ethnic families to underreport the incidence of domestic violence (The House of Commons, 2009). In general, crimes against women, particularly domestic violence, are generally underreported, which is why they also form part of the dark figures of crimes or crimes that go unreported (Berman & Berman, 2015). Literature related to domestic violence in African communities indicates that there are a variety of factors that may suggest the reasons related to the victims’ decisions on withdrawal of cases against their perpetrators. Izzidien (2008) conducted a research into African-‐Caribbean communities in the UK and found that there is a case of underreporting and case withdrawal by victims of domestic abuse (Izzidien, 2008). One factor that is identified as significant in the experience of victims from African and Caribbean communities is that of culture and social rules of the community. Literature suggests that women from African and Caribbean communities are generally more hesitant in filing criminal cases against the perpetrators of domestic violence because they are constrained by rules of their community and cultural practices (Wilson, Fauci, & Goodman, 2015). There may be a dominant view in these communities against reporting of domestic violence and family related matters to the police. Therefore, some of the reasons why women do not report domestic violence may be related to social factors that prevent women from reporting crimes against their husbands or intimate partners (The House of Commons, 2009, p. 12). Another factor that may be relevant to understanding the reasons why women from African and Caribbean communities withdraw cases of domestic violence against the perpetrators is that of sex or gender standards. Literature indicates that domestic violence is common in African communities, particularly because in Sub-‐Saharan African nations, domestic violence is accepted and is also usually blamed on the women victims on the grounds that they have transgressed sex standards (Uthman, Lawoko & Moradi, 2009). The use of gender relations as a way for preventing women from reporting violence against themselves suggests that there are cultural connotations to the structure of abuse within some communities in the UK (Gill, 2014). It may also be noted that legal and policy responses to domestic violence can be linked back to the strong feminist movement that developed in the 1970s in many countries around the Western world; it is this movement which is credited for creating advocacy around domestic violence (Groves & Thomas, 2013). Prior to this social movement, there was little social policy and control on domestic violence (Groves & Thomas, 2013). This suggests that domestic violence as a crime is largely a Western construct. In other words, victims or members of the Black communities may not see domestic violence in the same light as those from the White communities. This is especially true of immigrants who may not be exposed to the same liberal values of feminism in their native communities as British nationals (Gill, 2014). This may also explain why there is still a tendency for women from non-Western communities like the African and Caribbean communities to be hesitant to file cases of domestic violence or to withdraw criminal cases once filed. Another factor that may be relevant to understanding why women from African and Caribbean communities withdraw cases against their partners may be related to financial constraints. This may be especially true for those victims who have immigrated to the UK after marriage. Literature suggests that in some ethnic groups, there are marriages with overseas brides, where the brides may come from non-English speaking countries; such women are vulnerable to domestic violence and unable to take steps in response to violence because of their financial position as a new immigrant to a country where language and laws may be different and inaccessible (Anitha, 2008; Colucci, et al., 2013). There is also an interlink with cultural factors in such situations because many migrant brides may come from cultures that are more accepting of domestic violence and where domestic violence may not be treated to be a crime (Güvenç, 2014; Gary & Rubin, 2013). Women who come from these countries may be hesitant to file cases against their husbands and even if for some reason they do file such cases, they may withdraw these cases at a later point in time. Women from Black communities have a peculiar link to domestic violence not just in the UK but other countries as well, like the United States (West, 2014). There are cultural connotations to violence within Black communities that are documented on both sides of the Atlantic (Fuchsel, Murphy, & Dufresne, 2012; Pan, et al., 2015).

Findings

This section summarises the findings of the research. These findings are summarised thematically in the following paragraphs.

Normalisation of domestic violence and cultural factors:

There is normalisation of domestic violence in some cultures due to patriarchal nature of the societies and the gender based roles of men and women in such societies; domestic violence is normalised and incidence may be higher in such cultures because cultural values can play a role in normalising domestic violence (Fuchsel, Murphy, & Dufresne, 2012; Pan, et al., 2015). Due to the cultural contexts of domestic violence, Pan et al. (2015) points out that women of different cultures may experience domestic violence differently and also need different kinds of social support and services in dealing with the domestic violence. Culture can also be a strong mediator of the exposure and experience of domestic violence in a positive sense where cultural disapproval of domestic violence and misogyny may lead to lowered incidence of domestic violence (Colucci, et al., 2013). However, on the negative side, cultural values may lead to women being forced or coerced to not report incidence of domestic violence to the authorities with even fear of reprisals from the community being made to ensure that women do not report violence by their partners (Colucci, et al., 2013; Gill, 2014).

Immigrant status:

Women from Black communities, especially those who are immigrants may find it more problematic to deal with the authorities because of the links between domestic violence, abuse from family members, or partners and even forced labour or illegal immigration status (Anitha et al., 2008). There are vulnerabilities associated with immigrant status, with the women exposed to such vulnerabilities not being able to get or take access to help from authorities when they are exposed to domestic violence; for instance, they may not be able to get help from police because their partners may be withholding their visas, or threatening them that they will not allow them to apply for visas or threaten them with deportation or separation from their children (Anitha, 2008). Immigrant mothers belonging to the Black communities may continue to suffer abuse so that the authorities remain unaware of their undocumented immigration status (Anitha et al., 2008). There are laws to protect such women, even if they are undocumented immigrants, but women may not be aware of the protections afforded to them by the law and therefore, continue to suffer domestic abuse at the hands of the perpetrators. For instance, undocumented immigrant women who are suffering from domestic abuse can apply for Indefinite Leave to remain in the UK under the Domestic Violence Rules, with the option of fee waiver if they are destitute (NRPF Network, 2011).

Fear of social consequences:

Despite the provisions in the law and social welfare system to respond to domestic violence, there are attrition problems in the criminal justice system with some victims of domestic violence withdrawing their cases against the perpetrators. In some ways, the withdrawal of domestic violence criminal complaints can also be compared with the ways in which the criminal justice system treats rape cases with the attrition level being significantly high (Hohl & Stanko, 2015). In as much as women are the victims in majority of domestic violence and rape cases, the criminal justice system fails to provide justice in many cases (Hohl & Stanko, 2015). This argument is supported by Izzidien (2008) who has reported that the crime of domestic violence suffers from underreporting and withdrawal of criminal complaints because of the same factors that see underreporting and withdrawal of complaints in rape cases. Victims of domestic violence are either scared to report the crime or may be afraid of the social consequences of reporting it, or may be led by social or community censure to withdraw their criminal complaints once made (Izzidien, 2008).

Lacunae in the criminal justice system:

At the core of the question as to why some women may withdraw criminal complaints against the perpetrators of domestic violence against themselves is the question as to whether the criminal justice system itself is structured in a way that lets the victim of domestic violence down. The range of legal responses to domestic violence include civil as well as criminal provisions that have been created to respond to the problem. One of the important aspects of the legal response to domestic violence is that the statutory definition itself was given as recently as in 2012, under the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012 (Groves & Thomas, 2013, p. 47). Literature review has identified this lacuna in the criminal justice system that the actual attempts to counter the problem from a criminal law perspective is very recent in origin with the law only defining domestic violence in 2012 (Groves & Thomas, 2013). Nevertheless, domestic violence has become increasingly criminalised under the UK laws. At the same time, there are provisions of the civil law that are still relevant to the response to domestic violence. Literature review findings suggest that the use of both civil and criminal law to respond to the problem of domestic violence has led to the confusion for the victims of domestic violence as to which response to choose. It is argued that the blurring of lines between civil and criminal justice measures has led to the lack of clear and structured responses that can ideally operate in their own individual justice systems. For instance, the Family Law Act 1996 provides civil measures to the victim of domestic violence, wherein she can apply for a non-molestation order under Section 42 (G v F (Non-Molestation Order) [2000] 2 FCR 638, 2000). The Domestic Violence, Crime and Victims Act 2004, Section 1 punishes the offence of breaching a non-molestation order, which has been criticised as an attempt to penalise the non-compliance with a civil law order (Hitchings, 2006). Regardless, there is some evidence in literature that the victims of domestic violence may choose criminal law responses to civil law remedies as indicated by the decline in application for non-molestation orders (Burton, 2009). Burton (2009) argues that there is evidence to show that victims may find that civil law remedies are inadequate, but at the same time, the criminal justice system may not be protecting the victims of domestic violence as efficiently. Groves and Thomas (2013) agree that the criminal justice system may not be the most effective method for resolving complex social problems like domestic violence. The inadequacy of the Claire’s law may be used here to support this argument. Clare Wood was murdered in 2011, leading to the creation of a disclosure scheme called Clare’s Law, which was a scheme for introduction of a system allowing sharing of information about prior histories of violence. One finding in literature with respect to this scheme is that the complex questions of privacy involved in the implementation of the scheme make it too complex to be implemented (Fitz-Gibbon & Walklate, 2016 ). Women are reluctant to share such information as noted in the empirical evidence on the working of the Claire’s law (Fitz-Gibbon & Walklate, 2016 ). When seen in the context of the Black communities, for which literature already indicates that women are not forthcoming about domestic violence due to social pressures and patriarchal cultures (Anitha, 2008), it can be argued that there is a likelihood women will not come forward unhesitatingly, and even when they do and file criminal complaints, they may be forced by their communities to take back their complaints. Literature does indicate that there is lack of support and protection for victims of domestic violence, which is compounded by social and cultural factors of patriarchy in some communities (Bostock, Plumpton, & Pratt, 2009). There is also the problem of victim blaming, which may lead to the women withdrawing their complaints against perpetrators of the domestic violence (Bostock, Plumpton, & Pratt, 2009). Ethnic differences can play an important role in whether women victims of domestic violence ask for help and even when they do, how community pressures can make them withdraw their criminal cases (El-Khoury, 2004).

Take a deeper dive into Legal Responses to Bribery Crimes with our additional resources.

Conclusion

Since the criminal law response to the problem starting with the definition of the offence is fairly recent, it is possible that the criminal justice system is only just grappling with the problem and has been unable to come with effective responses that offer victims support and protection from the perpetrators of violence. Even when there are criminal law protections for domestic violence victims, there are social, and cultural barriers that come in the way of women victims asking for help, which frustrates the purpose of the criminal law. These barriers are made more complex by the cultural, social and ethnic factors. For instance, Black communities see patriarchal norms being responsible for the position of the woman within the family, which makes the women more vulnerable or hesitant to approach criminal justice system for fear of social repercussions. It can be surmised that even when women do approach the criminal justice system, they may withdraw the criminal complaints due to social and community pressures. Literature on law of domestic violence defines domestic violence from the statutory perspective, but it does not provide insight into victims’ experiences with the law; there is especially a paucity of literature on case withdrawal. In African and Caribbean communities, some research has been done with relation to domestic violence and the law, but there is little research on the reasons why women withdraw cases against the perpetrators of violence. Clearly literature suggests that there are a number of legal recourses that are open to victims of domestic violence. Therefore, it is a matter for concern as to why women from African and Caribbean communities would not take recourse to these remedies and options under the law or withdraw a case filed against perpetrators of domestic violence. While literature does indicate that there is underreporting and dark figures in domestic violence crime rate, there is little to show why there is underreporting and no research on why women withdraw cases filed against the perpetrators of domestic violence. Therefore, there is a gap in literature in this context. The factors that are identified as responsible for withdrawal are linked to culture and societal norms of the communities that the victims belong to. There are possible confusions due to the availability of both civil and criminal measures against domestic violence. The attitude of the police forces that respond to the complaints of domestic violence may be one of the possible factors for withdrawal of cases. There is a need for a more detailed research into these factors and linking these to the withdrawal of domestic violence cases. As of now, literature in this area is scanty. For this reason, the present research study also has certain limitations. One limitation is related to the methodology, which being secondary, the findings are based on what literature was available. As there is paucity of literature in this area, the findings are not reliable. There is a need for more detailed and primary research oriented research into this area. Future research into the same research question but with primary data will be more productive in leading to reliable findings with respect to the research question.

Refernces

- Abramsky, T., Watts, C., Garcia-Moreno, C., Devries, K., Kiss, L., Ellsberg, M., . . . Heise, L. (2011). What factors are associated with recent intimate partner violence? findings from the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence. World Health Organisation.

- Anitha, S. (2008). Neither safety nor justice: the UK government response to domestic violence against immigrant women. Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law, 30(3), 189-202.

- Bettany-Saltikov, J. (2012). How To Do A Systematic Literature Review In Nursing: A Step-By-Step Guide: A Step by Step Guide. London : Mc Graw and Hill.

- Bostock, J., Plumpton, M., & Pratt, R. (2009). Domestic violence against women: Understanding social processes and women’s experiences. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 19, 95.

- Burton, M. (2009). Civil law remedies for domestic violence: why are applications for non-molestation orders declining? Research Article. Journal of Social Welfare & Family Law, 31(2), 109.

- El-Khoury, M. (2004). Ethnic Differences in Battered Women's Formal Help-Seeking Strategies: A Focus on Health, Mental Health, and Spirituality. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology , 10(4), 383.

- Fuchsel, C., Murphy, S., & Dufresne, R. (2012). Domestic Violence, Culture, and Relationship Dynamics Among Immigrant Mexican Women. Affilia, 27(3), 263-274.

- Gill, A. K. (2014). Introduction: 'Honour' and 'Honour based violence': Challenging common assumptions. In A. K. Gill, C. Strange, & K. Roberts (Eds.), 'Honour' Killing and Violence: Theory, Policy and Practice . Basingstoke: Springer.

- Green, S., Higgins, J., Alderson, P., Clarke, M., Mulrow, C., & Oxman, A. (2011). Introduction. In J. P. Higgins, & S. Green (Eds.), Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions . London: John Wiley and Sons.

- Güvenç, G. (2014). Construction of Wife and Mother Identities in Women’s Talk of Intrafamily Violence in Saraycık-Turkey. nternational Perspectives in Psychology: Research, Practice, Consultation, 3(2), 76-92.

- Hall, A. (2014). 'Honour' Crime. In P. Davies, P. Francis, & T. Wyatt (Eds.), Invisible Crimes and Social Harms. The Palgrave Macmillan.

- Han Almis, B., Koyuncu Kutuk, E., Gumustas, F., & Celik, M. (2018). Risk Factors For Domestic Violence In Women And Predictors Of Development Of Mental Disorders In These Women. Archives of Neuropsychiatry.

- Hohl, K., & Stanko, E. A. (2015). Complaints of rape and the criminal justice system: Fresh evidence on the attrition problem in England and Wales. European journal of criminology, 12(3), 324-341.

- Pan, A., Daley, S., Rivera, L., Williams, K., Lingle, D., & Reznik, V. (2015). Understanding the Role of Culture in Domestic Violence: The Ahimsa Project for Safe Families. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 8(1), 35-43.

- The House of Commons. (2009). Domestic Violence, Forced Marriage and 'honour'-Based Violence: Sixth Report of Session 2007-08, Volume 1. London: The Stationary Office.

- Woodhouse, J., & Dempsey, N. (2016, May 6). Domestic violence in England and Wales, Briefing Paper Number 6337. London: House of Commons Library.

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts