Research methodology

Introduction

A case study design will be adapted for this study with a focus on Sierra Leone. Qualitative method will be adapted in data collection and analysis, ensures qualitative dissertation help. This method is considered most appropriate given the aim of the research and the research questions to be addressed in this study. A qualitative approach would allow the researcher to capture appropriately the voices of victims and their perspective on the question of justice. Data will be collected through semi structured interviews and focus groups. Where appropriate, some quantitative data will be collected for purposes of comparison with previous studies.

Research Question

The central research question this study seeks to address is whether transitional justice processes enhance the prospect of justice for victims of mass atrocities using Sierra Leon as a case study Specifically, the study seeks to examine the ICC transitional justice programme in Sierra Leone to establish its effectiveness as a model for peacebuilding in the post-conflict society of Sierra Leone. It will test the ICC model of justice from the perspective of victims and other key stakeholders to establish its effectiveness in justice delivery. Crucially, the study seeks to identify the most effective transitional justice model that has the potential to address the fundamentals of war crimes and deliver justice from the perspective of victims and key stakeholders in the affected society.

Hypothesis

International led transitional justice processes following armed conflicts and a gross violation of human rights, marginalise communities, rather than providing justice for communities, or addressing grievances of the past.

Relevance of the qualitative methods for this research

The project adopts qualitative research methods for the purpose of collecting and analysing the data. The rationale behind adopting a qualitative approach is that using this approach will enable the researcher to capture the detailed perspectives of the participants, their voices, views, stories, and experiences. Post conflict studies are complex for the reason that there are layers of narratives involved and for the researcher, these narratives become essential if the research is hoped to be representative of the different perspectives that are part of the larger narrative involved in the research. For this purpose, the study will apply qualitative data collection and analysis methods and it is hoped this will draw in and provide confirmation of conclusions from different study methods within the qualitative methodology. The study relates to transitional justice mechanisms in the context of post conflict Sierra Leone. As such, there are many challenges that are faced by the researcher that are in some way typical of the challenges faced in such research projects. Any social science research is complicated due to the issues of problems of access, sampling, ethics, etc. (Bowd & Ozerdem, 2010). These problems often get magnified in post conflict studies, such as the one involved in this research. Moreover, due to the post conflict stage in the area of research, there are other complex problems that may be faced by the researcher. Due to this reason, some researchers recommend the expansion of methodological techniques, so as to be enabled to meet the complex challenges of post conflict research or research conducted in post conflict environment or PCE (Bowd & Ozerdem, 2010). Transitional justice mechanisms have now become orthodox in post conflict environments as seen in the examples of countries such as Burundi, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, among many others. This is now the typical response to gross human rights violations. This response is motivated by the desire of the international community to initiate post conflict peace or as a legal response to crimes committed by the perpetrators or participants in the conflict (Robins, 2010). Such interventions leave little scope for the examination of the individuals or communities that are involved in the conflict. This is due to the prescriptive approach, which only focusses on the unidimensional issues related to such processes, such as, international law and transnational justice, or the working of the International Criminal Court in such situations. One study on the transitional justice mechanisms in Sierra Leone did utilize interview methods, however these interviews were limited to Public officials, UN officials, TRC officials, and members of the civil society (Apori-Nkansa, 2008). Needless to say, the interviewees’ belonged to the Centre rather than the periphery of the conflict impacted areas. As such, the different narratives were missed in the research and their ideas and perspectives did not form part of the findings of the study, which in the opinion of this researcher, compromises the findings of the research, limited as they are only to specific sections of the society. The method of data collection in the above mentioned research is not accepted in this research because this would not allow the understanding of different perspectives that are involved here. In this research, the researcher will consider the viewpoints and perspectives of members of different communities. Lee Ann Fujii’s important work involving post conflict Rwanda is critical of the fact

that most post conflict work is conducted “in the Centre” and that literature often prefers the Centre to the periphery, showing an urban bias (Fujii, 2009). Fujji kept her interview questionnaire open-ended and the consistent question she asked at the beginning of the research invariably was: “What do you remember from the period of 1990 to 1994?” (Fujii, 2009, p. 77). By keeping this open-ended question constant, she gave each interviewee the opportunity to define their experiences and perceptions. Her research is important because she was able to show the different perceptions and narratives in different communities, all of which were involved in the same conflict.

Looking for further insights on legal research project? Click here.

This research is also grounded in the same objective, that is, to give voice to the many narratives that can show the different perspectives of Sierra Leoneans towards transitional justice mechanisms. Qualitative approach is appropriate in researching this area is it is subjective and value laden, as most conflict issues are. These issues are interpretative in nature. This research uses semi structured interview techniques to collect data. The basic objective of the data collection is to enable the exploration of different perceptions of victims, community leaders and community members. These perceptions relate to transitional justice mechanisms applied in Sierra Leone after the end of the civil war. This is to aid the learning from communities about what justice is from their perspective.

As this research is conducted in post conflict environment, every care is taken by the researcher to manage methodological and ethical issues that often arise in such research projects. For this reason, the qualitative research methods are chosen. In other similar post conflict projects, qualitative research method has been employed by the researchers. In conflict situations, it is seen that the people are too involved to give detailed thought to the collection of base line data. At times, mixed methods approach is also applied, as was seen in the joint evaluation project of the conflict orphans’ reunification project, by Eritrea and UNICEF, which used a range and combination of quantitative and qualitative designs (Patel, 2000). However, quantitative research methods are purposefully disregarded by this researcher because, the focus is on the collection of data through narratives, which is best allowed by qualitative research methods.

Continue your exploration of Legal Research Project with our related content.

Qualitative research is more interested in the story from the individuals, or the community. In conflict situations, these stories may demonstrate varied experiences in the conflict. Conflict and post conflict research becomes challenging because there are layers of narratives that the researcher may have to address (Longman, 2013). In this research, the perceptions on transitional justice are being studied. In a similar research in post conflict Burundi and Rwanda, Longman has used qualitative research methodology to construct a survey that was used to gather information on sensitive subjects, including the interpretations of the past, and perceptions and attitudes towards justice and reconciliation (Longman, 2013). An important tactic used in that research was the inclusion of cross-checking questions that were built into the survey. This allowed the researchers to test the veracity of some of the assertions. This can also be a method for triangulation, as this would be involved in the validating of the findings of the research. Interview methods are also useful in conflict situations. However, here the method would have to be widely employed in order to get a larger and fairer idea of the situation. African centric research, from the Western perspective, can sometimes focus only on African elites for drawing out information. Elites, that is, members of the government, civil society activists, community leaders, or journalists, are generally easier to access, are well-informed, and speak English, French or Portuguese, making it easier for Western researchers to speak with them. Undoubtedly, interviewing elites is a useful component in data-collection, but it also suffers from certain drawbacks. The most prominent drawback is that African elites do show a disposition towards a Western worldview, which may shape their perceptions and understanding about important phenomena, such as morality, group identity and politics, and may differ widely from the viewpoint of the majority population (Longman, 2013). In transitional justice studies, this problem has been regularly noted (Longman, 2013). There is a tendency to ignore popular perspectives. Transitional justice mechanisms have now come to be frequently adopted in many post conflict African nations. Usually, the decision to adopt these mechanisms, is made by the government of the day. The larger perspective on the implementation of these measures is usually not sought, nor heard. Local perceptions may actually vary greatly on this issue. In particular, it is seen in the perspective of granting amnesty to perpetrators. In Sierra Leone, post conflict period has seen the adoption of the transitional justice mechanism. The Lomé Peace Accord of 1999, granted amnesty to Fodeh Sankoh, the leader of the Revolutionary United Front, and the combatants of the RUF. It would be interesting to see how far Sierra Leoneans accept the amnesty for Fodeh Sankoh and other RUF combatants, who have been instrumental for many atrocities during the ten year long Civil War in Sierra Leone. These popular perspectives may be at a variance with the government position or the perspectives of the elites. This was recorded in the earlier research into Rwanda transitional justice mechanisms, particularly, the perception towards the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda. The general perception for academics, fueled by the government reports and elite perceptions, was that the public of Rwanda was opposed to the Tribunal. The research however, showed that there may be a ‘mild’ disapproval for the Tribunal, due to the lack of knowledge about the working of the Tribunal. But perceptions recorded through survey did not show the grave opposition as was then presumed (Longman, 2013).

The limitations of the quantitative methods in its inability to gather information that is nuanced and textured and at multiple levels of social reality has come to be recognized (Kertzer & Fricke, 1997). There is now a growing body of researchers who conduct multi layered research in such areas of studies. As Collins says:

My sources are very heterogeneous. This is as it should be. We need as many angles of vision as possible to bear on the phenomenon. Methodological purity is a big stumbling block to understanding, particularly for something as hard to get at as violence (Collins, 2008, p. 32). Qualitative research is flexible and can be molded to fit the demands of complex studies, such as the ones involving post conflict environments, such as this research. This is because qualitative research is not based on pre fixed or pre-specified methods or hypotheses, that the researcher is bound to follow through the research (Willis, 2007, p. 54).

Triangulation

Triangulation helps to improve the validity of findings by using different data sources, or by asking the same kind of questions to the subjects in the sample population, but at different times. Triangulation is a method that is considered specific to qualitative research, although it is being used now in quantitative research as well. For example, one can compare survey findings, or compare survey findings with the census data (Bamberger, 2000). In the context of this study, as qualitative research is employed by the researcher, a triangulation method can be to compare the findings of the data (Bamberger, 2000). Validation of findings is important because it helps to generate credibility of research and strengthen the findings of the researcher. Qualitative research can be validated by following the four steps proposed by Lincoln & Guba: credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability (Lincoln & Guba, 1989). According to this, credibility or believability of the research findings can be established by the researcher. Transferability is the generalisation of the findings under different contexts or settings. This can be done well if the researcher takes care to describe the context of the research and the central assumptions. Dependability allows the data to be observable time and again. Confirmability is the degree of which the results are corroborated or confirmed by studies (Lincoln & Guba, 1989).

POPULATION

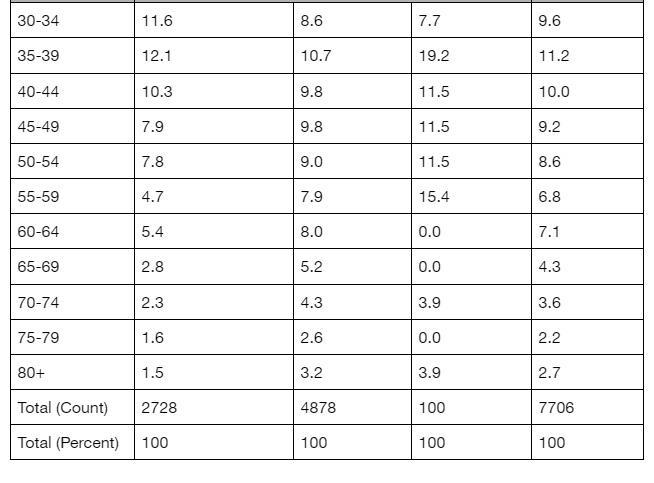

The research will take place in Sierra Leone, which the researcher has divided into two parts: Freetown, which is the capital, and the provinces. Due to their history, the provinces have also been sub-divided between the North and South, which is also of relevance to this research project. The North comprises predominantly of the Temne people, who are also the largest ethnic group in Sierra Leone; and the Limba people, who are considered to be the indigenous people and once rulers of the region. The southern provinces are dominated by the Mendes, who are also the second largest ethnic majority in Sierra Leone. The Sierra Leone Peoples Party (SLPP) is dominated by the Mendes and the All Peoples Congress (APC) is dominated by the Limba and Temne people. Most populations are roughly divided into 50 percent men and women. Sierra Leone and specifically the North and the East were no exception to such a demographic fact. Census materials from the office of Statistics indicated that Makeni, which is the regional headquarters of the North and the base for the first part of the field work has a population of 87,679. Makeni happened to be the home of most of the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) that waged a ten-year conflict on the people of Sierra Leone. The region also shares a boundary with neighbouring Guinea, a transit point for rebel groups to Guinea, Liberia, and the Ivory Coast. The most dominant ethnic groups in the area are the Temnes, followed by the Limbas, and the Fullas closely following them. There are also the Madingos, who are originally from Guinea, along with a few Mendes who migrated due to government postings. On the other hand, Kenema, in the East is dominated by the Mendes. Kenema has a population of 143,137. While population breakdown is not available yet for the North and East, in general, the 2012 census indicated that the Temne are the largest and about 35%, with the Mende 31%, followed by the Limba 8%, and the Kono 5%. Other ethnic groups include the Kriole 2% (descendants of freed slaves), the Mandingo 2%, the Loko 2%, and others making up 15%. While not each victim or perpetrator amongst these was interviewed, the statement-takers tried to be as thorough as possible by reaching all groups, including women and children. Through the process of interviewing, substantial numbers of statements were taken across Sierra Leone and neighboring countries. The table below illustrate the number of statements that were taken.

“Both male and female deponents gave statements with roughly equal proportions of motivations. Males were slightly more frequently direct victims of violations, while females were similarly slightly more likely to be witnesses to violence against family members”.

Selection Method

The choice of sample should be determined by the hypothesis proposed and the original research questions. Therefore, the research scheme has mapped out suitable places, while applying a stratified sample with target percentages of women, people of different ages, and people from different socio-economic levels. Key questions were asked of ordinary people, with follow-up questions asked in order to provide additional detail. It is pertinent to point out here that while there is a lot of literature that studies and critiques the Transitional Justice Mechanisms in Sierra Leone, such studies do not focus on actual victim, offender and community experience, that this research seeks to bring attention to. Stratified sampling will be useful here because, in this kind of sampling, the population is partitioned into regions or strata. Each stratum is useful for the purpose of selecting a sample (Thomson, 2012, p141). As each stratum serves as a representative sample of the population as a whole, stratified sampling requires that the units within the sample be as homogenous as possible. Moreover, it is important that for stratified random sampling, simple random sampling should be used for each stratum (Thompson, 2012, p,141).

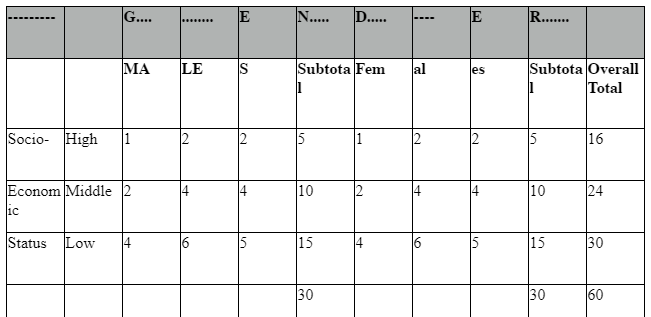

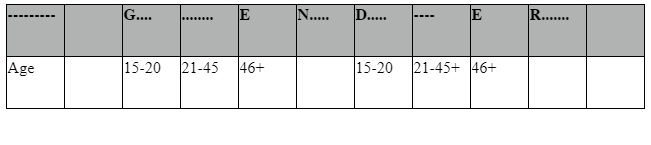

Due to limiting factors such as time, access to materials and resources, it is not going to be possible for researchers to gather data from the complete population and hence the need for representative sampling, which basically requires collecting data from a subset of the population. The choice of sample should be determined by the hypothesis proposed and the original research question. Therefore, a stratified purposeful sampling will be used, to ensure that the research represents the diversity of the total population within a set of respondents - in this case a random sample is not feasible. Therefore, to be quite 'scientific', it is necessary to encapsulate the social composition of the total population and its diversity. However, some representation of different generations was also needed, with socio-economic differentiation also being a key variable - and one reflecting wealth, education and position ('SES'= socio-economic status). Each category is cross-cut by the others, to avoid too many of these variables - only three were selected as they seemed to be the most significant in rural/peri-urban African settings. In addition, a sample of 30 “victims” in the North and also 30 “victims” from the East with similar war experiences will be used. Data collected from the TRC indicated that 3447 people from the North and 1802 from the East reported themselves as victims and among these 2728 were female and 4878 male. A sample of community stake-holders from both communities were also identified for comparison (see Attachment - table). Justification for interview community leaders is based on the fact that when all else fails it is they who have had to step in to address grievances that should have been addressed by the ICC. From the sample of about 73 community leaders, 14 were selected for interview. Whereas gender and approximate age can be identified reasonably easily, SES and knowledge of the war, of war crimes and of the transitional justice process are relative concepts and require subjective judgement to devise suitable criteria. Research took high SES to be indicated where a family had observable wealth - a well-built house, car, or a shop or a tractor or other small business. Middle SES was indicated by a corrugated iron roof and proper windows and some limited furniture. A thatched roof, holes rather than windows and only the most basic bed and stools, spoke of low SES. But these indicators were differently characterized in Sierra Leone. The questionnaires, designed, are also translated into the local Krio and Temne languages, and to be printed out with space for answers and boxes for standardized answers where appropriate. Research assistants will be trained to ask the questions, whilst I probe for further details and also do the recording - including when people go off on tangent, when an effort will be made to get their exact words if possible. Each questionnaire will be numbered and reassurance given to respondents. The table below is for the first village. It is a sample of 30, with evenly matched male and female sections. Research will seek out 1 young male of high socio-economic status, 2 middle-aged males of high socio-economic status and one older male of high socio-economic status etc until (up to 2 young females of low socio-economic status, 7 middle-aged females of low socio-economic status and 3 older females of low socio-economic status). Interview will not take place until research has found people who will fit into the categories.

The research has targets (%.. ) percentage of women, people of different ages, and people from different socio-economic levels – key questions are going to be asked of ordinary people – not jargon-loaded and followed up with subsidiary questions to tease out the possibilities. – e.g. under What the ICC should do? The first questions are going to be broad and open-ended to see what people think without prompting. These are followed-up by further questions prompted about security, justice, injustice and the grievances of the past. These themes were then echoed in relation to the other four questions (how fair the justice process was, who defined justice or victims? has community perception of justice been met? whose justice was it? Some exploration of the term ‘victim’ was also key to the research – where do people see themselves – as victims, members of the community, it leaders to their ethnic group, their religious group etc. All of these are important for different reasons. Do people see themselves as ‘citizens’, with rights and responsibilities, or as ‘subjects’ under constraint? Asking people about living without the state enabled follow-up questions about their own experiences of the civil war. The basic biodata is recorded every time: sex, age, education, ethnic group, religion, occupation, socio-economic level, birthplace, experience of migration. However, most of these questions were put to the end of the questionnaire to be used as a check list if the answers had not emerged beforehand. The questionnaire did not take more than 45 minutes and careful thought was given towards locating the respondents - where they should be interviewed - and whether I could afford to employ a local assistant whom I could train to ask the main questions, allowing me to concentrate on recording the answers in full.

SAMPLING

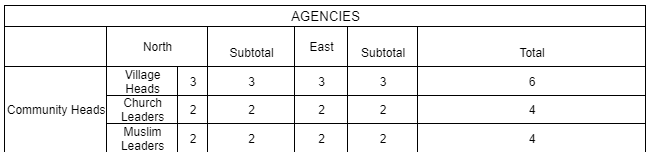

The present research seeks to use qualitative approaches, to be able to capture what Sierra Leoneans think about the crimes committed and the responses towards them, before drilling in into the affected or interest groups. The participants selected do not necessarily have to have been victims or perpetrators, but may also be from the general populace as a whole with opinions. The baseline survey in this case, while it may not be the preferred choice, could be used as a tool for obtaining useful data at the beginning of the research, though it would need careful design to counter the argument of being overly selective in the qualitative interviews. A baseline survey takes a quantitative approach to explore broader issues of importance to the topic. A random sample of adults (age 30-60) with more general questions will be used, such as: What do you think of the justice system? Did the ICC prosecute the right people? What caused the conflict? Was the compensation commensurable to the crimes committed? These are going to be statements with either agree, disagree, or yes or no questions. This research method is preferred because it fits into the context of the research and it allows a participant to talk freely, without hindrance and interference from the researcher. Such flexibility, as Gill pointed out, “also allows for the discovery or elaboration of information that is important to participants but may not have previously been thought of as pertinent by the research team” (Gill et al., 2008). To obtain an acceptable sample, two settlements (village/small) of manageable size, one from each of the main ethnic groups (Temne and Mende) and with contrasting war experiences will be selected. While methods such as mapping and conducting a “one in ten houses” exercise may work, a stratified sample with targets may prove more useful and will, therefore, be adopted. Data from the random sample can then be compared with that of these interest groups to corroborate or disprove conclusions drawn from other studies, and in the process eliminate issues of extreme bias due to the fact that I am an insider/outsider. The sample will consist of 75 respondents, split up between the (30) North, (30) East and 15 community leaders in total from both communities. Sample selection will be a random process and at Rokel and Wilkinson Road will be every third household. The second part of the study with the affected community will cover war crime issues with follow-ups and more detailed explorative questions. These will seek to capture the voices of people, especially those who have been silenced, to counter what is already known in the literature, to ask them about transitional justice issues and, in the process, uncover what has been lost. Most of the literature, especially on transitional justice issues, has examined the practitioners and justice this field work is not primarily interested in. What is missing in literature, are the stories of the victims, for whom a base line survey, and in-depth interviews will be done to capture their views. The interviews with key personnel—chiefs, village elders, and councilors—local political figures of consequence (including religious leaders), and the local heads of health, education, and the police/army. Interviews will use the same broad open-ended questions. This data could be compared with what ‘ordinary people’ say. Finally, during this time, the researcher will also engage in ‘participant observation’ in the sense of observing and recording people’s lives as the context for what they say, and attending any public happenings of political significance. These include, but are not limited to, events such as such as services in church and mosques, council meetings, the Chief’s court, and elections. There may also be a need for basic data on the population size and the local economy. Nevertheless, this may raise the issue of trust and security for researchers, especially since the interviews maybe detailed and probe in into issues the communities do not want to discuss. In this case, the research will seek to make use of gate-keepers who, in the case of Makeni and Kenema Villages, will be village heads and religious leaders. Three of these have been identified at Makeni and two at Kenema. Official requests will be sent after ethics permission has been received. Community samples will focus on victims, perpetrators and their families as well as community leaders.

Rationale for interview methods

Interviews are useful in leading to findings that may help verify the hypothesis of the research or lead to answers to research questions (Hammer & Wildavsky, 1989). Researchers are given access to data that reflects views, meanings, and definitions of situations and constructions of reality that may help the researcher to draw out findings through analysis of the data (Daymon & Holloway, 2011). Interviewees give a lot of insight to the interviewer, which helps the researcher understand the situation better through the perspectives of the interviewees (Yin, 2009, p. 23). Bogner and Rosenthal conducted a research in the Ugandan post conflict environment, where they used interviews and group discussions to bring out the narratives that in their opinion get lost or subdued in public discourse. The authors testify that the interviews taken by them are strongly illustrative of the fact that the narrative interview method is useful in supporting the interviewees “to verbalize what they have suffered” (Bogner & Rosenthal, 2014). Further, the authors say that the qualitative method analysis allowed them to thematize collective violence allowing them to give important insights into the perspectivity and the biases of these discourses (Bogner & Rosenthal, 2014). Thematic networks tool is a useful tool for analyzing data collected. Atrride-Sterling (2001) says that: “If qualitative research is to yield meaningful and useful results, it is imperative that the material under scrutiny is analysed in a methodical manner, but unfortunately there is a regrettable lack of tools available to facilitate this task” (2001: 386). Thematic network tool allows the researcher to organize a thematic analysis of qualitative data. The various themes that are salient in a text at different levels can be identified by the researcher. Then the researcher can use thematic networks to help in structuring and depiction of these themes. A web like network is resulted from the whole process of application of thematic tool to the available data, where the basic themes, organising themes and global themes can be depicted in a web like map. Basic themes make little sense if they are read in isolation. However, when read with other basic themes, a structure becomes visible, which is the organizing theme. An organizing theme would be a cluster of basic themes that relate to the same or similar issues. These organizing themes would then lead to groups of global themes, which are the macro themes that are super-ordinate in nature (Atrride-Sterling 2001: 389).

The full process of thematic analysis would be done in three broad stages. Stage one would see the reduction or breakdown of the text; stage two would require the researcher to explore the text; and finally, stage three would see the the integration of the exploration (Atrride-Sterling 2001: 390). Some authors advocate the use of in-depth interviewing techniques for the purpose of gathering data for analysis. For instance, Brouneus, says that in-depth interviews allow the researcher to guide the interviewee through an extended discussion on the topic, “leading the way with well-prepared, thought-through questions, and following the interviewee through active, reflective listening” (Brounéus, 2011, p. 30). In post-conflict research scenario, this can be a good method of gathering information and data from different sources, as a certain flexibility in guiding interviews is allowed in this method. In-depth interviews help to achieve a deeper understanding of the perspectives on the processes of war and peacebuilding. It can be used at two levels, as these are the predominant levels in such research. Thus, both elites and different groups of the population can be interviewed through in depth interviewing techniques. As it is, “at the grassroots level, in-depth interviews are used to learn from different subgroups of the population in order to better understand the challenges, possibilities and risks of peace” (Brounéus, 2011, p. 130). In-depth interviews can be structured or semi-structured.

This study uses a semi-structured interviewing technique. This allows the researcher to ask the initial guiding questions and then the interview can flow flow from there. There is no protocol or formal structured instrument that needs to be followed. As the post conflict environment is very complex, and it is challenging to draw out relevant observations and perceptions from the respondents, it was deemed better that the respondents be allowed to express themselves in a less formal or regimented environment, which is allowed by the semi-structured interviewing techniques (Ritchie & Spencer, 1994).

In a research involving post-conflict Bosnia, the researcher used semi-structured interviews to gather data on the perspectives and different narratives relating to peacebuilding, truth and reconciliation (Waller, 2015). Using a thematically constructed, semi structured interviewing technique, a series of open-ended questions were put to the respondents, who could answer yes or no and elaborate further depending on the level of their comfort with the questions (Waller, 2015). Another study, involving post conflict Uganda, to understand and analyze the various transitional justice mechanisms and record general attitudes on justice, used semi-structured interviews (Chirichetti, 2013). The research was mostly conducted through the use of semi-structured interviewing techniques. In post conflict research settings, focus groups are useful because they allow participation on often sensitive questions emanating from the violent period that the members of the groups have witnessed.

Rationale for Focus Groups

Focus groups involve collection of data through group discussions on topics that would be selected by the researcher (Soderstrom, 2011, p. 146). As the technique works, the researcher is able to collect the data through the process of questioning as well as interaction within the group. There is no formality within the discussion and participants in the discussions may answer the moderator or each other, or react to each-others’ statements (Soderstrom, 2011). A study for understanding sexual violence during conflict used focus groups of women to gather narratives (Tiesen & Thomas, 2014). The study was able to get women open up and talk about really sensitive and important issues of gender based sexual violence during the time of war.

In one study involving the veterans of the war in Timor-Leste, the researcher used focus groups to gather the narratives from the veterans as to their involvement in the post-conflict reconstruction process. The researcher was able to gather relevant information including some grievances of the veterans, which they were able to share within the focus group discussions (Peake, 2008). In another study, the researcher shows that focus groups, being a method of inquiry that is basically interactive in nature, allows the researcher to investigate post conflict situations that are sensitive and complex. This study involved the perspectives to transitional justice mechanisms in post war Croatia. The researcher found that focus groups helped to “effectively reflect independence of opinion; they lead to more truthful answers through spontaneity; they effectively probe taken-for-granted concepts; and they can more easily overcome distrust in post-conflict societies, especially with ex-combatants” (Sokolic, 2016).

Ethical Challenges

There are certain lessons that can be drawn from the Longman research in post conflict Burundi and Rwanda for the purpose of the present research (Longman, 2013). The first lesson is that local knowledge of existing conditions is important. In conflict situations, or even post conflict situation, with the coming in of the new government, people may hesitate to tell the truth, or rather their perceptions of the truth. Ongoing violence, authoritarian government, or community pressure, are some of the factors that impede the extraction of accurate information (Longman, 2013). The researcher has to earn the trust of the participants in order to gain information. Knowledge of local language and culture can help the researcher to create a comfort base. Emotional access is important in post conflict research, wherein the researcher is able to gain access to the community, or gain social acceptance within the community (Bowd & Ozerdem, 2010). Sierra Leone has gone through a long and difficult period of civil war. In such a situation, there are certain issues that are bound to be sensitive in nature. Therefore, it is essential that the research is conducted with sensitivity. This has been particularly pointed out by Smythe: Conducting research in a manner that uses people as objects without due regard for their subjectivity, needs and the impact of research on their situation is ethically questionable. This becomes particularly apparent in psychological terms, since respondents may be in a stage of denial in relation to the horrors that may have happened to them (Smyth, 2001, p. 5).

Conclusion

In conclusion, the question remains, is it the case that to be successful one has to choose a single paradigm? Does it mean that other approaches should be rejected? For advocates of transitional justice, its success or failure depends on flexibility of approach and the pattern of adoption. Many studies have been conducted which produce contradictory conclusions, mainly because they have all focused on single paradigms. Such has been the challenge and it has lad to the formation of the holistic approach. The term holistic can be defined as the tendency in nature to produce wholes from the orderly grouping of units, implying that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts and that all parts are important. This concept can be developed to mean an approach to transitional justice that draws together the various schools of thought, creating an opportunity for all parties and not just for some.

In the past decade the world has experienced and continues to experience challenges in the form of genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes. Therefore, as the analysis above showed, there is, for better or for worse, a need for accountability, whether symbolic or not, for the accused to account for the crimes committed. While this objective is clear, the problem has been in how to achieve survivors’ justice, bringing an end to and not prolonging the conflict and fostering reconciliation. However, to achieve this, the challenge has been to prioritize peace and not justice alone.

Take a deeper dive into Protecting Children in Armed Conflict with our additional resources.

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts