The Impact of Fasting on Heart Health: A Comprehensive Review

INTRODUCTION

In the modern world, cardiovascular diseases have proven to be a severe problem. According to the world health organization, 17.9 million people have died every year due to cardiovascular diseases. This accounts for about one-third of the overall deaths (Beltaief et al., 2019 p.247). The most affected individuals are those aged 45 and above. Fasting can potentially improve some of the risk factors related to heart health, offers valuable insights and hope for those seeking healthcare dissertation help. Alternate day fasting and time to time fasting are the popular approaches to fasting. Alternate day fasting involves having a normal meal a day and skipping meals or eating little the next day, while time restriction consists of eating only between particular hrs while fasting the rest (Higashiyama et al., 2021 p.627). Fasting has mainly been done for religious regions, making it hard to tell if it affects one's heart health.

Determinants of cardiovascular diseases such as age, gender and genetics are beyond human control; however, smoking, obesity, diabetes, hypertension and lack of physical activity are modifiable (Malinowski et al., 2019 p.673). The likelihood of occurrence of the diseases is hastened by the event of two or more risk factors. Fasting acts as a control risk factor that reduces the mortality rates and pathogenicity in patients with unrecognized cardiovascular diseases (Beltaief et al., 2019 p.247). With obesity on the rise, dietary changes are essential modifiable factors for cardiac ailments. Consumption of large amounts of vegetables, fruits and whole-grain bread are encouraged.

Obesity is among the major risk factors for heart diseases. The search for new and effective dietary solutions to reduce calorific intake and burn the existing fats in the body has been initiated (Park et al., 2016 p.42). Intermittent (time) fasting is gaining popularity as it is considered less restrictive than the traditional method of calorie restrictions. Meals are only consumed at strict time intervals within a day or a week. It consists of 16hours of fasting and 8 hours of the nutritional window. In severe cases, the healthy window is shortened by half, while in other cases 24 hour fasting periods with alternate 24 hour feeding times (Turin et al., 2016 p.73). The protocol may vary depending on an individual's choice and lifestyle. Athletes have used these fasting methods to achieve the desired body mass depending on their sports category.

According to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines for treating obesity-related illnesses such as heart diseases in adults, routine low calorific diets are recommended in cases with clinical justifications for weight loss (NICE, 2018). These low-calorie foods must supply all the necessary nutrients and should not be exercised for more than 12 weeks. Many studies have confirmed that human and animal models on weight loss using intermittent and time fasting diet reduces the risk of developing cardiovascular diseases as fasting modulates the effect of risk factors such as obesity, improper diet, insulin resistance and arterial hypertension (Yousefi et al., 2016 p.835-839).

Continue your exploration of Managing Coronary Heart Disease with our related content.

The hunt for novel and effective dietetic solutions focused on lowering calories, and body mass began in tandem with the growing obesity epidemic. The intermittent fasting (IF) diet is becoming increasingly popular. It is seen as less restrictive by many people when compared to established methods of calorie restriction (calorie restriction). It entails maintaining a regular daily caloric intake while calorie restricting for a brief period. Meals are only consumed over a specific period during the day or week (Wilson et al., 2018). The IF diet can be divided into two types. Carter et al. evaluated the effectiveness of the IF diet with the continuous energy restriction (CER) diet in the 5:2 system in 2016. During 12 weeks, the authors discovered that the IF diet could be a viable option for weight loss and glycemic control. Furthermore, for obese/overweight patients who find the CER diet challenging to maintain, the IF diet is a viable alternative.

Background of literature

The understanding of cardiac diseases is remarkable with origins in antiquity, centred initially on clinical observations. The history of this disease and medication dates back to in early 17th century. Following William Harvey's discovery, cardiologists pursued a pathway of descriptive anatomy and the pathophysiology of the disease in the 17th and 18th centuries (Grasgruber et al., 2016 p.316). In the 19th century, its correlations were studied and by mid of the century, pathophysiology and auscultations of the disease were understood. Advancements in the diagnosis and treatment of heart diseases were made in the 20th century. Medical specialities emerged in the early part of the 21stcentury. The introduction of the first instruments in the late17 century and early 20th century led to the creation of cardiology's speciality (Luengo-Fernandez et al., 2016 p. 138).

Cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of death for men and women in the United Kingdom. Heart diseases cause more than a quarter of all deaths in the UK. Each year, more than 160,000 people die, an average of 450 deaths per day (Sans et al., 2017). One person dies every 3 minutes, and more than 7.6 million people live with heart and circulatory diseases in the UK (Wilkins et al., 2017). On average, men are more than women accounting for more than 60% of the total population of cardiovascular patients. Coronary heart disease is the most common type of cardiovascular disease, which was ruled out in 2019 as the single best killer disease 2019 (Sans et al., 2017). There are more than 100 000 hospital admissions each year due to heart attacks, which means that one person is admitted every five minutes (Ma et al., 2020 p. 4). The survival rate of heart attack is minimal, and strokes cause around 34,000 deaths in the UK each year and is the most significant cause of disability. There are more than 30,000 people out of hospital cardiac arrest in the UK (Luengo-Fernandez et al., 2016).

The survival and preservation of species continuity depend, amongst others and on access to food. By observing a balanced diet-heart, patients can fast and continue taking their medications. According to expert knowledge, fasting can reduce vascular stiffness (Moss et al., 2017 p.15). Bilal Boztosun, the head of the cardiology department at Medipol Mega University Hospital in Turkey, observed that heart patients who undergo fasting do not experience deterioration of health compared to the non-fasting patients. He also added that the disease did not progress during the Muslim holy month of Ramadan (Beltaief et al., 2019 p. 247). Fasting also helps cardiovascular patients reduce their blood pressure and lose weight, provided they continue their medication. However, Boston also observed that fasting could cause cardiac patients' problems, especially during summer. Extreme loss of fluids and salt accumulation can lead to sudden drop in blood pressure, hence blackouts (Strongman et al., 2019 p. 1041-1054). This may lead to the progression of heart failure condition and may lead to death if care is not taken. The situation is risky for older adults with complaints of chest pains and shortness of breath. For patients in severe cases, fasting is risky as it may increase spontaneous attacks and strokes.

Rationale for Study

The growing global epidemic of heart diseases and ischemic complications has been fostered by dietary patterns and an increasingly sedentary lifestyle. The increased burden of obesity has increased diabetes incidences, which has increased the incidences of cardiac diseases (Wiciski et al., 2018 p.6). Heart disease prevention is a significant health concern not only in the UK but also across the globe. It is essential to identify and manage heart diseases and the associated risk factors. This calls for a study to be conducted on the regulatory measures that reduce the incidence of cardiovascular diseases.

Objective of Study

The overall objective of this study is to establish the effects of fasting on cardiovascular diseases.

The impacts of intermittent and time fasting on lipid metabolism

It also identifies other risk factors related to the onset and course of cardiovascular diseases.

This review also identifies different areas and bodies parts that are likely to be affected by cardiovascular diseases.

The study also recognizes the importance of historical and geographical factors in the changing profile of cardiac diseases worldwide.

Research Question

1. What are the effects of fasting on cardiovascular diseases?

2. What are the impacts of intermittent fasting on lipid metabolism?

3. What are the risk factors for cardiovascular diseases?

4. What is the currents status of cardiovascular diseases?

METHODOLOGY

In scholarly studies, research methods are techniques of gathering and analyzing necessarily relevant information to fulfil the main aim and objective of the study. It is regarded as a scholarly manual of conducting and academic tasks significant in problem-solving (Pandey,2021). For this study, qualitative analyses were adopted for systematic review. It enabled reflections of studies that had already been conducted and their finding verified before being used in making decisions. This allowed the researcher to gain deep insight and interpret the phenomena under study by understanding the alternative risk factors for cardiovascular diseases.

Literature search

The topic on the effects of fasting on cardiovascular diseases is a bit broad and requires a lot of research from journals and articles from PubMed, Google scholar, FINNA and MEDLINE. These sources contain a rich database that has been scientifically published and approved for use. The literature reviewed articles were highly preferred in this review as they focused on data collected from existing peer-reviewed sources (Wang, Benchi and Theeuwes, 2018 p-173). The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) method was considered the most suitable for searching eligible literature publications.

The main keywords used to ensure the focus of the study was maintained 'cardiac diseases', "vascular complication", 'fasting' and 'cardio vascular diseases. Deploying various databases widens the range of preferences for a given study (Ali et al., 2018 p. 133-147). This makes it more comprehensive and ensures all aspects of the problem under investigation are covered. The articles used were limited to peer-reviewed only and those that were reliable for the study. An assessment was done to ensure that the content obtained addressed the objective and research question.

Eligibility criteria

After 450 publications from Websience, Science Direct, and PubMed, only eight papers were used in this study. Due to duplication, 300 articles were deleted, and 130 articles were omitted because they did not match all planned selection criteria. Due to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 12 papers were removed from the analysis. The search was limited to countries in the United Kingdom. Data was gathered via electronic sources, allowing for a literature search. (Eriksen, Mette & Frandson, 2018 p.69). The investigation excluded articles that were published more than five years ago. Only eight studies out of a total of 450 were found to be suitable for review. The others were overlooked due to geographic location, language barriers, publication dates, and a lack of information on the research topic.

Critical appraisal

When analyzing the quality of the works of literature to be used in this study, Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) qualitative checklist was used. This method was critical in determining the validity of the literature, particularly the findings. Before being incorporated in this evaluation, the Generalizability of studies not done in the United Kingdom was assessed before being included in this review. The CASP framework is critical in establishing the Generalizability of research and the trustworthiness of its findings (Creswell & Creswell, 2011). Furthermore, because its application follows the logical implications of the study's parts, this approach is simple.

Research design

The study design included empirical studies published as peer-reviewed literature or conference papers that used qualitative, quantitative or mixed data collection approaches. Qualitative research, particularly those that used semi-structured interviews and content analysis articles, were given more attention.

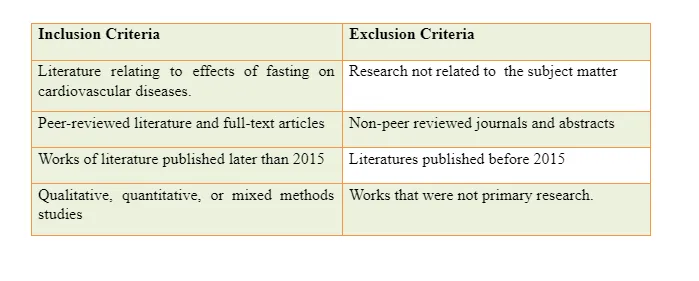

Even though mixed methods studies were included in this evaluation, they were analyzed independently from the quantitative data. Unpublished thesis and book chapters, as well as abstracts, were excluded. The criteria for inclusion and exclusion are summarized in the table below.

Data collection

Data collection is gathering data from all relevant sources to solve the research problem, test the hypothesis, and assess the results. Data collecting methods are classified into two categories: secondary data collection methods and primary data collection methods. Secondary data has previously been published in books, newspapers, magazines, journals, and other online resources (Blumenberg and Barrows, 2018 p.768). These sites have a wealth of information about the study topic in business studies, nearly independent of the nature of the issue. As a result, using a suitable set of criteria to pick secondary data for use in the study is critical to boosting the research validity and reliability. These criteria include, but are not limited to, the date of publication, the author's credentials, the source's reliability, the quality of discussions, the depth of analyses, and the text's contribution to the advancement of the research area. In this research, a secondary source of data has been used as it contains rich sources that have already been tested against reliability and validity.

Systematic Reviews (Narrative)

A systematic review is defined as a systematic and explicit review of the evidence on a formulated question that uses systematic and detailed methods to identify, select, and critically appraise relevant primary research, as well as to extract and analyze data from the studies included in the review (Cumpston et al., 2019 p. 142). Reproducible and transparent approaches must be employed. Describes and evaluates past work but does not detail the processes used to find, select, and assess the studies under consideration. It is used in overviews, discussions, and critiques of prior work and to identify current knowledge gaps, justify future research, and scope the types of treatments that can be included in a review.

Data analysis

A meta-analysis was not conducted because of the different samples studies, measured outcomes, and pre-treatment intervention procedures. The Cochrane Handbook advises against comparing "apples and oranges," as this will mask significant differences. They point out that assessing behavioural and public health interventions is particularly difficult due to the wide range of samples, techniques, and outcome measures (Blumenberg and Barrows, 2018 p.769). Instead, the interventions were classified according to the kind of barriers they were designed to overcome. To assess which interventions were effective, a count of the number of interventions in each category that enhanced each outcome was undertaken.

Pico framework

Studies Included

Eight key publications were discovered and used in this study after stringent selection, and appraisal processes were employed. The publications chosen include valid and reliable evidence that appears to be relevant to the investigation. The material that was chosen include:-

1. Aksungar F.B., Topkaya A.E., Akyildiz M. (2015)Interleukin-6, C-reactive protein and biochemical parameters during prolonged intermittent fasting. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2015;51:88–95. doi: 10.1159/000100954. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

2. Bhutani S., Klempel M.C., Berger R.A., Varady K.A. Improvements in Coronary Heart Disease Risk Indicators by Alternate-Day Fasting Involve Adipose Tissue Modulations. Obesity. 2010;18:2152–2159. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.54. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

3. Cambuli V.M., Musiu M.C., Incani M. (2018) Assessment of adiponectin and leptin as biomarkers of positive metabolic outcomes after lifestyle intervention in overweight and obese children. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008;93:3051–3057. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-0476. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

4. Chen, W.W., Gao, R.L., Liu, L.S., Zhu, M.L., Wang, Y.J., Wu, Z.S., Li, H.J., Gu, D.F., Yang, Y.J. and Zheng, Z., 2020. China cardiovascular diseases report 2018: an updated summary. Journal of geriatric cardiology: JGC, 17(1), p.1.

5. Okamoto Y., Hotta K., Nishida M., Takahashi K., Nakamura T., (2015). Novel modulator for endothelial adhesion molecules: Adipocyte-derived plasma protein adiponectin. Circulation. ;100:2473–2476. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.100.25.2473. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

6. Sutton E.F., Beyl R., Early K.S., Cefalu W.T., Ravussin E., Peterson C.M. Early Time-Restricted Feeding Improves Insulin Sensitivity, Blood Pressure, and Oxidative Stress Even without Weight Loss in Men with Prediabetes. Cell Metab. 2018;27:1212–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.04.010. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

7. Wilkins, E., Wilson, L., Wickramasinghe, K., Bhatnagar, P., Leal, J., Luengo-Fernandez, R., Burns, R., Rayner, M. and Townsend, N., 2017. European cardiovascular disease statistics 2017.

8. Wilson R.A., Deasy W., Stathis C.G., Hayes A., Cooke M.B. (2018) Intermittent Fasting with or without Exercise Prevents Weight Gain and Improves Lipids in Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Nutrients. 2018;10:346. doi: 10.3390/nu10030346. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

RESULTS

Numerous researches on weight loss using an IF diet based on human and animal models confirm the lowered risk of cardiovascular disease. This is due to the IF diet's ability to modulate various development risk factors, including obesity, poor diet, insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, and arterial hypertension. The frequent use of deficient calorie diets (VLCDs) in the therapeutic regimen of obesity in adults is not advised, according to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines for the treatment of obesity in adults (NICE, 2018). According to this institute, such a method should be recommended when rapid weight loss is clinically justified, and it must include all necessary nutrients. It should also only be done for a maximum of 12 weeks (continued continuously or intermittently).

Findings

Wilson et al. researched 8-week-old mice to demonstrate the effects of the IF diet on body weight and LDL cholesterol levels (39 males and 49 females). These mice were given high-fat and sugar meals 24 weeks before being separated into five groups after 12 weeks. Overweight control mice (OBC) were in the first group; mice without intervention (CON) were in the second group; mice on the IF diet were in the third group; mice on high-intensity interval training (HIIT) were in the fourth group; and mice on a combination of IF and HIIT were in the fifth group (Wilson et al., 2018). Compared to the HIT and CON groups, both IF and IF plus HIIT caused a decrease in body weight and low-density lipoproteins (LDL). These findings show that weight loss is beneficial even when high-fat and sugar diets are consumed together.

Weight loss and changes in lipid parameters result from the aforesaid biochemical transformations of lipids and the IF diet. According to research conducted by Surabhi et al., using alternate days on an empty stomach—ADF (alternate day fasting)—for 2–3 weeks resulted in a 3 per cent reduction in body weight. In contrast, prolonged attempts resulted in an 8 percent reduction in body weight and reduced visceral fat mass (Wilson et al., 2018 ). Total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides, and low-density cholesterol (LDL) levels and the size of these molecules were all lowered. Changes in these variables reduce the risk of coronary heart disease (CHD). The concentration of glucose, which is the primary energy source, lowers while the body is not eating. Glycolysis is slowed down. Glycogen reserves in the liver are depleted, and the gluconeogenesis process, which consumes lipids, is triggered.

Furthermore, insulin and IGF-1 (insulin-like growth factor-1) levels in the blood are decreased, while glucagon levels rise. Fatty acids are released by fat cells during the lipolysis of triacylglycerol and diacylglycerol. They are subsequently transferred to liver cells, where they undergo -oxidation and are transformed into -hydroxybutyrate (BHB) and acetoacetate (AcAc), which are then released into the bloodstream and used as a source of energy by body cells, including the brain. Neuronal networks in the brain adjust cellular and molecularly in response to such metabolic changes. As a result, their functionality and resilience to stress, injuries, and diseases has improved.

Inflammation is a crucial component of growth. Homocysteine, interleukin 6 (IL6), and C reactive protein (CRP) are pro-inflammatory substances that contribute to atherosclerotic plaque formation. The effect of the IF diet on lowering the concentrations of the above-mentioned pro-inflammatory components were proven in research conducted by Aksungar et al. The study included 40 healthy people with the correct body mass index (BMI) who fasted throughout Ramadan and 28 healthy participants with the same BMI index who did not fast. One venous blood sample was taken to determine the levels of the above-mentioned pro-inflammatory substances (Aksungar et al., 2015).

Adiponectin is a collagen-like plasma protein whose levels drop with atherosclerosis, insulin resistance, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Adiponectin secretion from adipocytes is increased when the IF diet is used. The levels of plasma Adiponectin and body weight have an inverse relationship. Cambuli and his colleagues studied 104 obese children. They examined Adiponectin concentrations before and after a year of dieting and increased physical activity. This concentration grew by 245%. Adiponectin levels rose in lockstep with bodyweight loss (Cambuli et al., 2018). Adiponectin performs its duties by binding to two types of adiponectin receptors: AdipoR1 and AdipoR. It inhibits monocyte adherence to endothelial cells, which has anti-atherosclerotic and anti-inflammatory properties. On vascular endothelial cells, it also suppresses the excretion of vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1), endothelial-leukocyte adhesion molecule 1 (ELAM-1), and intracellular adhesive molecule 1 (ICAM-1). Ouchi et al. demonstrated this in vitro with human aortic endothelial cells cultured for 18 hours in the presence of adiponectin (Cambuli et al., 2015). THP-1 line monocyte adherence to human aortic endothelial cells was measured using an adhesion assay generated by tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha). ELISA was used to measure the compounds' expression enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Adiponectin's anti-atherosclerotic properties have been demonstrated in a variety of animal models and cell cultures.

Okamoto and his associates discovered that adiponectin has an anti-inflammatory effect in human macrophages by suppressing the synthesis of CXC 3 receptor chemokine ligands utilizing reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (real-time) and ELISA testing (Okamoto et al., 2018). In vivo experiments on mice without apolipoprotein E/adiponectin revealed an increase in IP-10 in plasma, as well as an increase in T lymphocyte concentration in arteries and atherosclerosis, when compared to mice lacking apoE alone

Bhutani et al. 2016 research demonstrate that the ADF diet has activity in regulating adipokines. As a result, it has anti-sclerotic and cardioprotective properties. There were 16 obese persons in the study, 12 women and 4 men. It lasted ten weeks and consisted of three dietary intervention stages. The first two weeks were spent in a control phase, the next four weeks were spent on an ADF diet with feeding times monitored, and the final four weeks were spent on an ADF diet with self-fed nutrition time by the patient (Bhutani et al., 2016). After eight weeks, there was a decrease in leptin concentrations on the ADF diet, which was linked to a reduction in body weight and fat content. The resistin concentration reduced dramatically after following the ADF diet, which was most likely due to decreased body weight.

Studies on the effects of the IF diet on the body were carried out on male C57/BL6 mice at the State University of New Jersey. To achieve an obese phenotype, all animals were fed a high-fat diet (45 percent fat) for 8 weeks (Wilkins et al., 2017). After that, the mice were separated into four groups: The mice in the control group ate a high-fat and libitum diet (group 1); exercise groups ate a high-fat diet for two days, then fasted for five days (group 2); low-fat diet (10 percent fat/group 3); and a group with IF ate a low-fat diet (10 percent fat/group 4). (group 4).

In comparison to the control group, all experimental groups showed decreased body weight and body fat content after 4 weeks of diet use. The concentrations of glucose following an oral glucose load, as well as insulin tolerance, were studied. Compared to the control group, all research groups had decreased blood glucose, glycated haemoglobin levels, and enhanced insulin sensitivity (Chen et al., 2018). In human population research in Manchester, the effects of the IF diet on weight loss were also established. Women in their premenopausal years who were overweight or obese were given a six-month challenge to cut calories by 25% by following a Mediterranean diet. Women lost weight, had their abdomen circumference reduced, and their fatty tissue content decreased when the trial ended. Weight loss had a favourable influence on happiness as well. Women were also examined for insulin sensitivity and glucose levels in addition to their body weight.

The findings also demonstrated that the IF diet had a positive effect on glycemic markers. The HOMA index was used to assess insulin resistance in the study group. The study also looked at persons with diabetes to see how the IF diet affected their glucose metabolism. In patients with type 2 diabetes, IF diets were found to have particularly beneficial effects. Type 2 diabetes is a prevalent metabolic illness that affects people all over the world. It's linked to increased obesity rates and sedentary behaviour (Chen et al., 2018). Many problems, such as cardiovascular disease, neuropathy, retinopathy, and kidney disease, can be avoided by limiting the development of diabetes. In people with type 2 diabetes, the IF diet effectively improves glucose metabolism. This was shown in the Diabetes Remission Clinical Trial (DiRECT), where diabetes mellitus was seen after a hypocaloric diet. For 12 weeks, participants under constant medical supervision ate roughly 850 calories each day [71]. In persons with type 2 diabetes, weight loss has been shown to normalize fasting blood glucose, lower glycated haemoglobin (HBa1c), and improve insulin sensitivity.

Sutton et al. 2018 attempted to determine if health benefits in humans are dependent on weight loss or other non-weight loss causes. Early time-restricted feeding (eTRF), a type of intermittent fasting that includes eating early in the day according to the circadian rhythm, was used to create proof-of-concept research. Individuals with prediabetes were randomized to either eTRF (6 h feeding time, dinner before 3 p.m.) or a control group at random (12 h feeding time). It was established that eTRF improved beta-cell responsiveness, insulin sensitivity, blood pressure, oxidative stress, and appetite after 5 weeks of monitoring (Sutton et al., 2018).

Risk Assessment Biasness

The risk of bias assessment (also known as "quality evaluation" or "critical appraisal") helps to ensure that evidence synthesis results and findings are transparent. Each included study in your review is usually subjected to a risk of bias evaluation. Evidence syntheses attempt to ensure that their findings are free of bias (Long et al., 2020). Individual studies included in synthesis may consist of biases in their findings or conclusions, such as design errors that raise issues about the findings' validity or overestimating the intervention impact. Outside of systematic reviews, risk of bias assessment is usually not required when using evidence synthesis approaches.

The critical appraisal skill program, often known as the CASP tool, was used to assess these papers' reliability, validity, and relevance (Larsen et al., 2019). These tools are utilized in my research to evaluate the literature I've chosen. This tool has proven to be quite valuable in assessing research articles, and it is used to measure irrelevancy in research. The CASP tool was used to find similarities in research publications, which allowed for the incorporation of pertinent data. The literature has been extensively structured, boosting the accuracy and quality of this research, as seen in the results and discussion section (Long t al, 2020). However, there are several gaps in this study's findings, which are concentrated on publishing dates, language, and geographic location. The study question has received little attention in the United Kingdom. The publishing dates limited the utilization of potentially accurate information, resulting in bias.

DISCUSSION

Researchers aren't sure why, but it appears that fasting — drastically restricting food and drink for some time — can enhance some risk factors associated with heart health. Fasting can be done in a variety of ways, including alternate-day fasting and time-restricted feeding. During alternate-day fasting, you usually eat one day fast or eat very little the following (Wiciski et al., 2018). Eating solely during particular hours of the day, such as 11 a.m. and 7 p.m., is a time limitation. This section discusses the findings from the previous research on the effects of fasting on cardiovascular diseases.

Because many people who fast daily do so for health or religious reasons, it's difficult to say what effect regular fasting has on heart health. These people are less likely to smoke, which can help minimize the risk of heart disease (Wilson et al., 2018). On the other hand, fasting diet followers may have superior heart health than non-fasters, according to certain research. Fasting regularly and improved heart health could be linked to how your body metabolizes cholesterol and sugar. Fasting regularly can help lower your LDL cholesterol or "bad" cholesterol.

Fasting is also known to help your body digest sugar more efficiently. Intermittent fasting may protect the heart even after a heart attack or stroke. According to observational research, Muslims with a history of ischemic cardiomyopathy have a lower incidence of acute decompensate heart failure during Ramadan than during other times of the year. 32 The Intermountain Heart Collaborative Study Group pooled 648 patients from two trials involving Latter-day Saints in a meta-analysis. They examined the incidence of coronary heart disease, defined as at least one coronary artery with a 70% stenosis, between those who fasted once a month and those who did not. With an odds ratio of 0.65, those who adhered to the fast had a decreased risk of coronary heart disease (CI 0.460.94). 33 Although human data on intermittent fasting following a cardiovascular incident is limited, these observational studies imply that it has a beneficial effect (Surabi et al., 2017).

While intermittent fasting and calorie restriction are similar, it's vital to distinguish between the two because they can have different biological effects. One significant contrast is that, unlike caloric restriction, intermittent fasting does not always imply calorie restriction. The results of intermittent fasting on cardiovascular risk variables (such as blood pressure, fasting glucose, and lipid profile) can be detected in people even when calorie intake is not reduced during Ramadan (Aksungar et al., 2015). They have lower blood pressure on average throughout this month. In obese people, intermittent fasting and calorie restriction appear to have equal benefits on improving lipid panels, whereas alternative day fasting groups considerably influence fasting glucose. Although intermittent fasting is not the same as caloric restriction, the evidence shows that fasting reduces various cardiovascular risk factors such as diabetes, hypertension, and cholesterol. Despite the small number of research, intermittent feasting's capacity to promote heart health appears promising.

Limitation of evidence

More research is needed to assess the processes, efficacy, target populations, and safety of intermittent fasting in humans. There are various intermittent fasting regimens available, ranging from 12- to 16-hour daily fasts to the 5:2 method, and it's unclear whether one is optimal for cardiovascular health, especially since evidence suggests that intermittent fasting regimens should follow circadian cycles. Some regimens may be easier to stick to than others (Jin et al., 2016). Future research should look into the safety of each intermittent fasting technique. Future research should determine the time of intermittent fasting required before cardiovascular benefits occurred, in addition to establishing effective intermittent fasting regimens customized to different patient populations. During observational Ramadan research on humans, benefits happened within a month.

Intermittent fasting for prolonged periods may result in continuing reductions in cardiovascular risk factors and incidents. It should also be determined whether these benefits last longer than the duration of intermittent fasting. Intermittent fasting improved blood pressure in rats, but this improvement was reversed 3–4 weeks after returning to an ad libitum diet.4 However, obese adults who were on intermittent fasting for 8 weeks and then transitioned back to their regular diet for 24 weeks maintained their lower cholesterol and glucose levels (Bhutani et al., 2016)

Dietary factors play a significant influence in the prevention of cardiovascular illnesses. Nutraceuticals, which include many beneficial components for the human body, deserve special attention. Polyphenols, resveratrol, carotene, polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), curcumin, and zinc are just a handful of these compounds. Carotenoids are an essential component of the Mediterranean diet (Bhutani et al., 2016). They can be found in vegetables (particularly carrots), fruits, and seaweed. It's yet unclear how effective they are at preventing cardiovascular events. Due to the action on lipoxygenaseS, they are ascribed to antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities.

Resveratrol is a nutraceutical that deserves special attention. Trans 3, 5, 4′-trihydroxystilbene is the biologically active isomer. Resveratrol is abundant in grapes, so red wine has the highest quantity, but it is also found in blueberries, peanuts, and pistachios. It contains antioxidant qualities and a cardioprotective impact, making it helpful in treating a variety of ailments. It has been discovered that resveratrol may help to lower blood pressure. Wiciski et al. found that a daily dose of 10 mg/kg of resveratrol enhances BDNF levels and decreases vascular smooth muscle cells (Chen et al. 2018).

Hypercholesterolemia is prevented by resveratrol. Chen and his associates corroborated this in mice testing, finding a reduction in lipid markers after 8 weeks of a high fat diet and treatment of resveratrol at a level of 200 mg/kg per day. In mice, increased lipid metabolism is linked to increased 7-hydroxylase activity after resveratrol treatment. The liver receptor, LXR, controls the enzyme (Ouchi et al., 2015). It is involved in converting cholesterol to 7-hydroxycholesterol and then to cholic acid, which leads to increased bile acid production and decreases cholesterol in hepatocytes.

Polyphenols also help to lower the lipid profile. Mulberry leaves have the highest concentration of them. Polyphenols are thought to play a function in reducing lipid levels by inhibiting the enzymes responsible for their formation. Fatty acid synthetase, 3-hydroxy-3-methyl glutaryl CoA reductase, and acetyl-CoA carboxylase are examples of these enzymes. As a result, polyphenol extract from mulberry leaves reduces fatty acid accumulation in the liver by activating the AMP protein kinase pathway. Other polyphenols present in black tea theaflavin lower the lipid profile as well. According to Jin et al. research, this has been proven in rat models fed a high-fat diet (Ouchi et al., 2015). At the same time, the rats were given black tea extract containing highly refined combinations of theaflavins. After the study was completed, it was discovered that total cholesterol, LDL-C, and triglycerides had all fallen modestly. In addition to stopping the activity of alanine transaminase and hepatic lipase, theaflavin lowered the atherogenicity index.

Implications of the results

Fasting regularly and improved heart health could be linked to how your body metabolizes cholesterol and sugar. Fasting regularly can help lower your LDL cholesterol or "bad" cholesterol. Fasting is also known to benefit the way your body processes sugar. This can help you avoid gaining weight or developing diabetes, both of which are risk factors for heart disease (Jin et al., 2017). However, there are worries regarding the potential adverse effects of fasting on particular persons or in certain situations. Fasting is not advised for: those suffering from eating problems as well as those who are underweight, those who are pregnant or breastfeeding, as well as those who are on diabetes medication and End-stage liver disease patients Fasting's effects on heart health, are positive, but more research is needed to see if regular fasting can lower your risk of heart disease. If you're thinking of fasting regularly, talk to your doctor about the benefits and drawbacks. Remember that eating a heart-healthy diet and exercising consistently can help your heart.

The study's limitations and strengths

The author decided to focus on peer-reviewed publications and did not look for this work in the "grey literature." Even though a systematic review was undertaken, certain research were probably overlooked, which could be due to a lack of standardization in terms used in this field. Despite this, the 8 articles matched the requirements for a considerable body of evidence that might be used in a meta-analysis.

CONCLUSION

Although cardiovascular death rates have improved, the reduction has recently halted, and mortality in 35–64-year-old males and females in the United Kingdom has increased. 1 Obesity and poor diet are significant, modifiable factors to the rise in cardiovascular disease, with a 13 percent attributable risk to cardiovascular mortality. 2 Caloric restriction, which entails restricting calories taken over some time, is one of the dietary strategies that has been found to reduce cardiovascular risk. Caloric restriction has been associated with weight loss, lower blood pressure, and improved insulin sensitivity in humans.

Intermittent fasting has been shown in human trials to have cardiovascular benefits. Intermittent fasting appears to have a favourable influence on numerous cardiovascular risk factors, including obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes, while the underlying processes are unknown. In addition, intermittent fasting has been linked to a better result following a cardiac episode. Future research into the potential of intermittent fasting to enhance cardiovascular outcomes should be encouraged by these findings.

The IF diet reduces several risk factors for cardiovascular disease development and, as a result, the occurrence of these diseases. Because the body goes through a glucose-ketone metabolic transition, fatty acids and ketones become the primary energy source (G-to-K). It reduces body mass and has a beneficial impact on lipid profile parameters, such as total cholesterol, triglycerides, and LDL cholesterol, by influencing the biochemical transformations of lipids.

It's unclear if these advantages are attributable to weight loss or non-weight loss mechanisms. Rule compliance following a predetermined diet following the circadian rhythm is critical to the success of any diet. Despite the many advantages of the intermittent fasting diet, it is not without its drawbacks. Fasting is not recommended for those with hormonal abnormalities, pregnant and breastfeeding mothers, or diabetics since it might be harmful. Furthermore, the intermittent fasting diet is not recommended for persons who have eating disorders, have a BMI of less than 18.5, or are underweight. The IF diet and its variants have grown in popularity in recent years. This diet is good for losing weight and can also be utilized as a non-pharmacological treatment. This has been demonstrated in several human and animal investigations. Before beginning the IF diet, however, individuals' existing health and situation should be examined.

Bibliography

- Aksungar F.B., Topkaya A.E., Akyildiz M. (2015)Interleukin-6, C-reactive protein and biochemical parameters during prolonged intermittent fasting. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2015;51:88–95. doi: 10.1159/000100954. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ali, N.B. and Usman, M., 2018. Reliability of search in systematic reviews: Towards a quality assessment framework for the automated-search strategy. Information and Software Technology, 99, pp.133-147.

- Beltaief, K., Bouida, W., Trabelsi, I., Baccouche, H., Sassi, M., Dridi, Z., Chakroun, T., Hellara, I., Boukef, R., Hassine, M. and Addad, F., 2019. Metabolic effects of Ramadan fasting in patients at high risk of cardiovascular diseases. International journal of general medicine, 12, p.247.

- Bhutani S., Klempel M.C., Berger R.A., Varady K.A. Improvements in Coronary Heart Disease Risk Indicators by Alternate-Day Fasting Involve Adipose Tissue Modulations. Obesity. 2010;18:2152–2159. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.54. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenberg, C. and Barros, A.J., 2018. Response rate differences between web and alternative data collection methods for public health research: a systematic review of the literature. International journal of public health, 63(6), pp.765-773.

- Cambuli V.M., Musiu M.C., Incani M. (2018) Assessment of adiponectin and leptin as biomarkers of positive metabolic outcomes after lifestyle intervention in overweight and obese children. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008;93:3051–3057. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-0476. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M.J., Chandler, J., Welch, V.A., Higgins, J.P. and Thomas, J., 2019. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: a new edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 10, p.ED000142.

- Grasgruber, P., Sebera, M., Hrazdira, E., Hrebickova, S. and Cacek, J., 2016. Food consumption and the actual statistics of cardiovascular diseases: an epidemiological comparison of 42 European countries. Food & nutrition research, 60(1), p.31694.

- Higashiyama, A., Wakabayashi, I., Okamura, T., Kokubo, Y., Watanabe, M., Takegami, M., Honda-Kohmo, K., Okayama, A. and Miyamoto, Y., 2021. The Risk of Fasting Triglycerides and its Related Indices for Ischemic Cardiovascular Diseases in Japanese Community Dwellers: the Suita Study. Journal of Atherosclerosis and Thrombosis, p.62730.

- Luengo-Fernandez, R., Leal, J., Gray, A., Petersen, S., & Rayner, M. (2016). Cost of cardiovascular diseases in the United Kingdom. Heart, 92(10), 1384-1389.

- Chen, W.W., Gao, R.L., Liu, L.S., Zhu, M.L., Wang, Y.J., Wu, Z.S., Li, H.J., Gu, D.F., Yang, Y.J. and Zheng, Z., 2020. China cardiovascular diseases report 2018: an updated summary. Journal of geriatric cardiology: JGC, 17(1), p.1.

- Malinowski, B., Zalewska, K., Węsierska, A., Sokołowska, M.M., Socha, M., Liczner, G., Pawlak-Osińska, K. and Wiciński, M., 2019. Intermittent fasting in cardiovascular disorders—an overview. Nutrients, 11(3), p.673.

- Moss, A.J., Williams, M.C., Newby, D.E. and Nicol, E.D., 2017. The updated NICE guidelines: cardiac CT as the first-line test for coronary artery disease. Current cardiovascular imaging reports, 10(5), p.15.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2020.

- Okamoto Y., Hotta K., Nishida M., Takahashi K., Nakamura T., (2015). Novel modulator for endothelial adhesion molecules: Adipocyte-derived plasma protein adiponectin. Circulation. ;100:2473–2476. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.100.25.2473. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, P. and Pandey, M.M., 2021. Research Methodology Tools and Techniques.

- Park, C., Guallar, E., Linton, J.A., Lee, D.C., Jang, Y., Son, D.K., Han, E.J., Baek, S.J., Yun, Y.D., Jee, S.H. and Samet, J.M., 2013. Fasting glucose level and the risk of incident atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases. Diabetes care, 36(7), pp.1988-1993.

- Sans, S., Kesteloot, H., Kromhout, D.O. and Force, T., 2017. The burden of cardiovascular diseases mortality in Europe: task force of the European society of cardiology on cardiovascular mortality and morbidity statistics in. In Europe', European Heart Journal.

- Strongman, H., Gadd, S., Matthews, A., Mansfield, K.E., Stanway, S., Lyon, A.R., dos-Santos-Silva, I., Smeeth, L. and Bhaskaran, K., 2019. Medium and long-term risks of specific cardiovascular diseases in survivors of 20 adult cancers: a population-based cohort study using multiple linked UK electronic health records databases. The Lancet, 394(10203), pp.1041-1054.

- Sutton E.F., Beyl R., Early K.S., Cefalu W.T., Ravussin E., Peterson C.M. Early Time-Restricted Feeding Improves Insulin Sensitivity, Blood Pressure, and Oxidative Stress Even without Weight Loss in Men with Prediabetes. Cell Metab. 2018;27:1212–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.04.010. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Turin, T.C., Ahmed, S., Shommu, N.S., Afzal, A.R., Al Mamun, M., Qasqas, M., Rumana, N., Vaska, M. and Berka, N., 2016. Ramadan fasting is not usually associated with the risk of cardiovascular events: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of family & community medicine, 23(2), p.73.

- Wang, B. and Theeuwes, J., 2018. Statistical regularities modulate attentional capture independent of search strategy. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 80(7), pp.1763-1774.

- Wilkins, E., Wilson, L., Wickramasinghe, K., Bhatnagar, P., Leal, J., Luengo-Fernandez, R., Burns, R., Rayner, M. and Townsend, N., 2017. European cardiovascular disease statistics 2017.

- Wilson R.A., Deasy W., Stathis C.G., Hayes A., Cooke M.B. (2018) Intermittent Fasting with or without Exercise Prevents Weight Gain and Improves Lipids in Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Nutrients. 2018;10:346. doi: 10.3390/nu10030346. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Yousefi, B., Faghfoori, Z., Samadi, N., Karami, H., Ahmadi, Y., Badalzadeh, R., Shafiei-Irannejad, V., Majidinia, M., Ghavimi, H. and Jabbarpour, M., 2016. The effects of Ramadan fasting on endothelial function in patients with cardiovascular diseases. European journal of clinical nutrition, 68(7), pp.835-839.

Looking for further insights on The Global Diabetes Epidemic? Click here.

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts