Comparing Coffee and Wine Cultures

Introduction

This dissertation will ask the question: will coffee cupping become the new wine tasting? The subject matter of coffee is a personal interest and having worked in this field for three years (and counting) my knowledge and understanding has significantly developed. This dissertation is an outlet to put forward my understanding (through experience, conversations and research) of coffee and wine, followed by an educated proposal for a potential future for them. Before the final argument can be made, what coffee and wine actually are, the production methods of coffee and wine, and the positions of coffee and wine in society (both historically and currently) need to be understood. By the end of chapter one, where these elements will be broadly discussed, the reader should be able to begin to draw out similarities between the production of coffee and the production of wine. Chapter two concentrates on literature review, which includes studies that narrow down to specific methods within the production of coffee and the production of wine that will have an affect on the final outcome, whether that be flavor, body or yield among others. By this point in chapter two, the reader should be able to be able to confidently identify similarities between the production of coffee and the production of wine. The reader should also have a much more detailed knowledge of the production of coffee and the production of wine, and understand how the discussed methods influence the final outcome. The final part of chapter two will discuss the development of coffee and wine in society. It will do this by identifying specific lifestyles that coffee and wine clearly fit in to and describing the ideologies of those lifestyles. By the end of chapter two, the reader should have a good understanding of the production of coffee and the production of wine, how certain techniques within those productions can be adjusted to bespoke the final outcomes, and the positions of coffee and wine in society. Only what will be discussed in chapter three and the argument to say that coffee cupping will become the new wine tasting. Chapter three is where the final argument will be made based on the observations made in chapter two. Everything that will be discussed in chapter one and chapter two will used in the final argument. Chapter three will discuss specialty coffee and specialty/independent coffee shops. It will include the more recent positions in society. By the end of chapter three, and in turn the dissertation, the reader should have a sufficient understand of the production of coffee and the production of wine, how their final outcomes can be bespoke, and the historical and current positions of coffee in society. Only when the reader understands all these things, can they make an informed decision as to whether coffee cupping will come the new wine tasting.

CHAPTER ONE

Background

The study on wine and different tastes noted over the years has also attracted attention on the side of coffee cupping. According to Carvalho and Spence (2018), people across the western cultures are poor in terms of naming the flavors and smells. This is different for both the coffee and wine experts whose smells as well as flavors are part of the daily routine. According to the studies conducted by Croijmans and Majid (2016), both the wine and coffee experts have shown significant differences while trying to define the menus, taste note and even the placards. In a debate dubbed “Coffee is the new wine”, Croijmans and Majid (2016) shows a long history of the significant wine profiles, with cupping trying to bring coffee at par with the wine flavors and taste. Most of the coffee growers around the world are working hard enough produce coffee in terms of varying tastes, which are showcased in the production of wine (Da Ros et al., 2017). The subsequent emergence of coffee cupping is driving producers towards tasting, analyzing as well as grading types of the bean in separate characteristics. Just as wine, grading coffee is becoming a complex process while trying to create the flavor profiles. Carvalho and Spence (2018) respond to the question of coffee cupping and why it might have attracted a lot of attention with time. First, wine tasting has a history which has been used as an avenue for food knowledge. Wine tasting grew into an evolution that has equally influenced the cosmopolitan lifestyle with a big impact seen in coffee cupping (Hagiwara, 2004). Notably, the taste of coffee is essentially influenced by the place it was grown and the means or the way it was roasted. Smelling the type of coffee has been given a priority in profiling the coffee and just like wine, coffee can over 850 kinds of the traits, aromas and even the chemical composition. So, what is coffee? The term coffee, used on its own, is essentially a blanket statement. It can be used as a loose description for the commodity during any part of its production, it is only when a specific part of its production is being described that more specific terminology is needed. Coffee begins as the fruit of a tree in the botanical family Coffea, which grows best in a number of tropical regions at varying altitudes (Williams, 2018). A brief history of coffee making and coffee profiling indicates that in 1565, the Great Siege of Malta took place between the Ottoman Empire and Malta, in which a number of Ottoman invaders were taken prisoner and kept as slaves. There they continued to make coffee for themselves and their captors which marked coffee’s introduction to Europe. Coffee quickly advanced from Turkish prisoners to the Maltese high society and general population which was a precursor for new local coffeehouses to be formed. As word of Maltese coffee spread, the German traveller Gustav Sommerfeldt endorses the Turks of Malta as being ‘the most skillful makers of the concoction [coffee]’ (Sommerfeldt, 1671).

The coffeehouse was introduced in London in 1652 by Pasqua Rosée, a Greek servant of a British merchant, two years after they returned from residing in Smyrna. Rosée’s coffeehouse proved extremely popular before it inspired another 3,000 to open in the following 48 years. An old Turkish saying, ’Not the coffee, nor the coffeehouse, is the longing of the soul. A friend is what the soul longs for; coffee is just the excuse (Williams, 2018, p. 24); an accurate rationale for the coffeehouse’s success in society. The invention of the first espresso machine in the 1901 by an Italian named Luigi Bezzera showed a potential for mass production of cups of coffee, Bezzera’s invention relied on pressurized steam to make an espresso. However, this did not create enough pressure to extract a decent espresso so was later replaced by Achille Gaggia’s lever and spring solution, which delivered hot water from the boiler straight through the ground coffee at a higher pressure making an espresso quicker and of higher quality. This system of using hot water instead of steam revolutionized the espresso machine, leading to a development by another Italian, Ernesto Valente, of motorized pumps to deliver the water at a consistent pressure (Williams, 2018). These significant Italians figures allowed a smooth transition between first wave and second wave coffee. First wave being the growth of coffee, where it was just made and drank, people did not understand that a higher quality was attainable. The second wave was a mass production, largely facilitated by the espresso machine, and commercialization (establishments such as Starbucks, Costa and Cafe Nero). Second wave coffee may be of a different quality to first wave, but due to its commercialization its focus is on quantity instead of quality.

Background on Coffee and wine production

Continue your exploration of Uganda's Refugee Hosting Challenges with our related content.

The fruit from the coffee trees are known as the coffee cherry, and the seeds of these cherries are the coffee beans as established by the coffee research (n.d). This cherry has a similar structure to a standard cherry with regards to its skin, inner pulp and central seed. The outer three layers of the fruit (pericarp), there is the epicarp (outer skin), mesocarp (pulp and mucilage together) and endocarp (parchment), also collectively called the cascara. The epicarp is made up of cells with thin walls that contain chloroplasts and are permeable enough to absorb water (Cotter and Valentinsson, 2018). The color of the skin begins as green due to the presence of chloroplasts and then, as it matures, turns red or yellow depending on the variety of the coffee. The mesocarp is a slimy, gel-like substance is where the fruit’s sugars mix with the water absorbed from its local atmosphere. How these sugars are utilized in production is instrumental in developing the flavor profile of the specific coffee and are one of the most popular ways to bespoke coffee (Hagiwara, 2004). The endocarp is made up of three to seven layers of fibrous cells that harden through maturity to provide structure and support. The seed (coffee bean) is made up of the spermoderm (silver skin), endosperm and embryo. Whether the silver skin contributes much more to the seed than just being its skin (structural shell) is currently unknown. However, during roasting this skin, or ‘chaff’, sheds and is discarded. The endosperm is the main body of the coffee bean. Although the oil content and cell wall thickness varies throughout the endosperm, the single type of tissue is consistent. This tissue is made up of a number of different chemical compounds, both soluble and non-soluble such as caffeine, which, together with its oils, provides the predecessor for the bean’s final flavor and aroma (Mussatto et al., 2011). The embryo is responsible for the coffee tree’s reproduction only and has no effect on the beans final taste

Once the cherries are ripe enough, they are generally hand-picked by coffee farms and then taken to a mills to be processed. Processing is essentially how the seed is removed from the cherry. These processes vary in principal and each affect the bean’s final flavor and aroma. The two most used processes are washed and natural. During the washed process, the cherries are soaked and significantly agitated in water before having the seed removed mechanically (Da Ros et al., 2017). During the natural process, the cherries are spread out in the sun to dry and allow the pericarp to naturally ferment and fall away from the seed (Neves et al., 2006). The final process is pulped natural, which is a combination of the washed and natural processes. During the pulped natural process, the cherries are soaked in water and the skins are mechanically removed (similar to if they are being washed), and then the resulting fruit being spread out in the sun to dry (Ubeda et al., 2019). The differences these processes have on the flavor and aroma of the final bean will be illustrated in chapter two. The seeds that have been removed from the cherries are now called green coffee beans and are ready to be roasted to exported (usually directly to importers or roasters themselves). Roasting is a method whereby the green coffee beans are intensely heated to trigger reactions between the chemicals and sugars in each bean. By doing this, it also caramelizes the beans’ sugars which provide sweetness in its final flavor. By adjusting the time in which the beans are roasted, roasting is one of the main methods that is used to bespoke and fine-tune a coffee’s flavor (Ubeda et al., 2019). The longer the roast time, the darker and more intense the flavor becomes. Once the beans have been roasted, they are ready to be sold for both domestic and commercial use. In the context of the coffee shop, this is when the barista will take the roasted coffee beans and use their skills and knowledge of extraction to produce a cup of coffee for a customer.

The production of wine has general similarities to coffee production with regards to harvesting and processing. The first step is the harvest, grapes are picked either by hand, by cutting bunches by their stems, or by machine depending on the size of the vineyard. Machine harvesting is a much more quick and efficient way to harvest, as opposed to harvesting by hand which can be very labor intensive but can produce superior results (Da Ros et al., 2017). Following the harvest, bins of these grapes are transported to the winery (these can be located elsewhere or at the vineyard itself) for step two - destemming. Before the grapes can be crushed, they must first be decoupled from their bunches using a destemmer. The destemmer does exactly what its names imply; it removes the stems from the grapes as well as lightly crushing them (Iannone et al., 2016). Following the destemmer, the grapes are properly crushed, meaning their skins are broken enough to let the juices to flow out naturally. For white wine making, the resulting pulp-skin amalgamation is put straight into a press which extracts the juice and leaves behind the skins. After the juice has been extracted it must be racked. Racking is where the juice is filtered out of the settling tank, where the juice has been left for enough time for the sediment to settle to the bottom, into a second tank ready for fermentation. However, for red wine making, the initial pulp-skin amalgamation is immediately fermented as the red color from the grape skins provides the red color for the wine as well a contribution of tannins. The pressing and racking of red grapes occur after the fermentation process, but before the wine is aged. Fermentation occurs when yeast that is added to the tanks reacts with sugars in the grapes and produces alcohol and carbon dioxide (Da Ros et al., 2017). In red wine production, the byproduct carbon dioxide pushes the grape skins to the surface. This means that, because red grape skins are a significant part of red wine production, they must be remixed with the rest of the juice either by hand or machine - punch down or pump over (Mussatto et al., 2011). The punch down technique is when the winemaker physically punches the skins down underneath the surface in order to mix with the rest of the juice. The pump over is when the winemaker mechanically pumps the juice from the tank back into the top of the same tank. There are benefits and drawbacks (figure 3) to each of these techniques depending on the size of the winery and the aim of the winemaker.

Following fermentation and pressing, the wine must be aged in order for it to develop in flavor and body. Ageing is essentially when wine is left for a period of time for it to settle and develop (FuseSchool - Global Education, 2016). Wine can be aged in either big stainless steel tanks or, more traditionally, in oak barrels. Both steel tanks and oak barrels will produce significantly different flavor profiles, each developing more as time progresses. As it will explained in the following chapters, this step in the production process is one of the main steps in which a winemaker can bespoke a wine and achieve a predetermined profile (Ubeda et al., 2019). The final step in the wine prosecution process is for it to be bottled. It is rare that bottling is done by hand due to the volume of bottles that require labeling and corking. The wine is then ready to the distributed.

Research Problem

For many years, the history has indicated an evident evolution with regards to profiling wines with regards to their flavor and the smell. Perhaps, any discussions or debates on food knowledge drew reference from wine profiles where the test for flavor and smell were easily conducted. However, the trend seems to have slightly changed following the increased consumption of coffee across the world. With the background details drawing attention towards coffee processes and increase of coffee flavors and smells, the continuum seemingly favor the new wave of coffee taste which also contributes towards food knowledge. The concept of coffee cupping, on the other hand, bolsters the trend of coffee profiling which substantially replaces the key role played by wine profiling. Therefore, the research needs to dig deep on how coffee cupping is substantially becoming the new wine tasting.

Research aim and objectives

The main aim of this research is to establish the chances of coffee cupping becoming the new wine tasting. This can be supported by the following objectives.

To determine the emerging trend of coffee cupping

To draw comparisons between coffee cupping and wine tasting

To establish the favoring factors of coffee cupping over wine tasting

Chapter Two: Literature review

Introduction

This chapter provides the systematic review of the key studies that attract comparison of coffee and wine production, as well as the growing concept of coffee cupping which seems to displace wine tasting in the framework of food knowledge. The systematic review doubles as the methodology in this research as the study aids to establish the findings felt in line with the research aim and objectives. According to Croijmans and Majid (2016), the systematic review on coffee and wine production should focus on reliable findings on whether smells and the flavors apply to the two beverages. This implies that the chapter maintains its focus on the studies associated to Coffee production and regional growth, then its roasting, followed by brewing and the last stages before the production is completed. Subsequent to the writing regarding coffee, the methods within wine production will be discussed and similarities to coffee production drawn out and compared (Decanter 2017). The final part of the chapter will discuss in more detail the coffee culture in more recent years and its influence on the stereotypical ‘yuppie’ lifestyle. It will also discuss how the elitist element of wine has deteriorated and its artisan side has grown, with thanks to wine making techniques being established and long-standing.

Coffee production

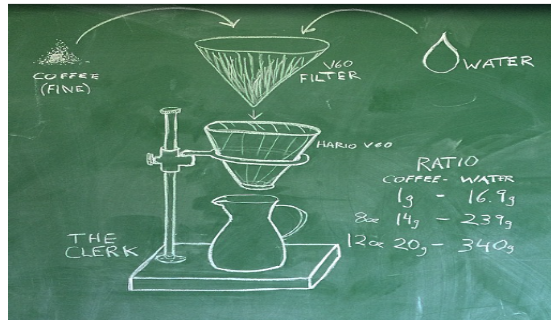

The main thing to be aware of with regards to the regional characteristics of coffee is that the altitude at which the coffee is grown is one of the most influencing elements that affect its taste. Why? Simple anaerobic respiration provides the magic that has never been seen before (Sommerfeldt, 1671). In order to plants to be able to grow and produce fruit they need energy, which is produced from aerobic respiration (primarily) - where glucose (sugars) and oxygen react to create energy as one of the products. However, when there is a lack of oxygen, meaning anaerobic respiration occurs. As a result of this, the fruit is on the tree for a longer period of time, meaning more sugars can be developed which makes the coffee more sweet. Anaerobic respiration is also what occurs in fermentation. This means that coffee that is grown at higher altitudes will be more deprived of oxygen, meaning it will have more glucose and produce a sweeter coffee. Coffees that are grown at lower altitudes are relatively bitter since there is more oxygen and less glucose is needed (Williams, 2018). This is why coffees from Ethiopia will typically be sweeter than coffees from Brazil, because Ethiopia has larger mountain ranges which enable coffee to be grown at higher altitudes. This is a good example of how regional characteristics in the growing process affect the coffee’s taste. With regards to coffee roasting, it is the roaster’s responsibility to best bring out the characteristics of the specific coffee. When the coffee beans are roasted, the sugars are caramelized and the familiar flavor is born. It is down to the roaster to work out the best roast profile for that coffee - how long is the optimum roast time and at what temperature? The longer and hotter the roast, the darker the beans will be. This is the main element in roasting that the roaster has to get correct to control the final taste of the coffee. The darker the roast, the more bitter the taste. After roasting is generally when the beans are sold to shops and coffee shops. A benefit of this is that a coffee shop can discuss with the roaster how they want their coffee roasted - lighter or darker and bitter. The next two factors that will be discussed are generally in the domain of the barista and the request of a coffee shop customer - brewing method and milk (Specialty Coffee Association). As mentioned briefly in chapter one, the main ways of brewing coffee are by percolation, infusion and espresso (although technically espresso is a form of percolation) (Da Ros et al., 2017). V60 filter coffee (figure 4) is a good example of percolation. Percolation is when the water-soluble compounds in the ground coffee are extracted and dissolve in the brief amount of time that the hot water flows through it. This process is illustrated in figure 4 and demonstrated in figure 5. In figure 4, an example coffee-water ratio is given. This ratio is what the barista deems to be the best brew ratio for that specific coffee - any more coffee and it may be over-extracted, tasting slightly bitter, any less and it may be under-extracted and taste slightly sour (Specialty Coffee Association). Cafetière (or French press) (figure 6) filter coffee is a good example of infusion. Infusion is when the ground coffee is submerged in hot water so the water-soluble compounds are extracted and dissolved.

Once the brew time is finished, the extracted grounds are separated from the water by the filter which is pushed down inside the cafetière. Since the coffee will be in contact with the water for a lot longer in a cafetière, it must be ground a lot courser to compensate and significantly reduce the surface area of the coffee and the overall extraction.

Espresso is a more intense version of percolation in the way that the ground coffee is compressed into a ‘puck’ and the hot water forced through at a high pressure from the espresso machine. Due to the high pressure, the final taste is much more intense. A benefit of this is that the characteristics of the specific coffee can be identified much easier, but also it is easier to determine if the coffee has been under or over-extracted or where the taste stands on the sourness-bitterness scale. The final element that can affect the taste of the coffee is when it is drunk with milk. This will obviously dilute the flavor of the coffee, but it also has another scale of flavors that is similar to the bitterness-sourness scale of coffee. For example, for each of the standard coffee shop drinks - macchiato, cortado, flat white, latte or cappuccino - steamed milk is required. If the milk is steamed to approximately 40 degrees Celsius, it will taste slightly cheesy or yogurt. If the milk is steamed to a much hotter 70 degrees Celsius, it completely loses its flavor and may taste slightly burnt when added to espresso (FuseSchool - Global Education, 2016). The optimal target temperature in specialty coffee shops is between 55 and 60 degrees Celsius - cool enough to be drunk immediately, yet hot enough to be classed as a hot drink. This optimal temperature is the when the milk is at its sweetest.

Wine production and characteristics

When discussing the regional characteristics of wine, a significant element is whether a certain grape can grow in a certain location or not. For example, the river Garonne that runs through Bordeaux - the grape Cabernet Frank grows better east of the river than west because of the different geographical conditions (Wine). Therefore, the characteristic of that more eastern region would be similar to the variety of grape that grows there. If someone prefers a more full-bodied wine with a slight spice, they would be best to find a wine that has been produced east of the river in Bordeaux; this is because that region has characteristics of the Cabernet Frank grape which is relatively spicy by nature. According to Decanter (2017), Appassimento is an Italian specialist method used within wine making. It is similar to the way coffee is naturally processed in the way that the grapes are laid out in the sun to dry, and by doing so the natural sugars are kept and dried which affects the final taste of the wine, making it sweeter overall.

The next step includes maceration time and cold soaking. Both of these terms are used to describe the part of the process in which the grape skins are in contact with the juices. Cold soaking is as how the term states, the skins are soaked and submerged in cold water (Fillion, 2002). What this does is it extracts the fruit flavors and color from the grapes without with bitter tannin or engaging the fermentation process. This allows the wine to become more full-bodied and intense in flavor (Wine). The total time that the skins are in contact with the juices is called the maceration time. Winemakers can significantly extend or reduce this time to fit the specific profile they are trying to achieve. This is similar to coffee brewing in the way that the longer the coffee is submerged in the water, the more body and flavor the coffee will have due to its longer contact time. The final and most common way that the final flavor of wine can be bespoke is by ageing. Over time, the flavors, aromas and colors of wine can change drastically. Ageing is when the wine is stored, before bottling, in order for these different elements to develop it is down to the winemaker to determine how long, and in what container, is best for that specific wine or to achieve the desired profile (Wine). Red wines can generally be aged for longer than white wines; however it is possible for wines to be aged for too long. The container in which the wine is aged is usually the biggest element that can influence the flavor of the wine, aside from the natural characteristics of the grape itself and other elements already discussed. According to Wine (n.d), ageing in oak barrels not only adds a subtle vanilla flavor to the wine, but also increases its oxygen exposure which mellows tannins and helps it reach optimal fruitiness (Wine). Wines that have been aged in a ‘charred’ oak barrel will also have a subtle smokey flavor. Red wines are the most common wine to be aged in oak barrels. The second kind of container that wine is often aged in is a stainless steel tank. Steel tanks keep the wine fresher due to their ability to regulate oxygen exposure (Fillion, 2002). Zesty white wines benefit the most from being aged in steel tanks.

Comparison of coffee cupping and wine tasting

In the early stages of the coffee house, a big part of their ethos was to provide a place for people to meet and converse, whether socially or professionally. Is this still the case in recent years? Or have peoples’ ethos shifted? Is a place to meet people still one of the main purposes for a coffee house? There is an argument to say that ethos has shifted. In many industries, there has been a shift in priorities that has resulted in employees working longer hours under more pressure in order to meet targets and expectations. This development in society has supported the shift in coffee culture, from an excuse to converse with friends, to a tool that is used to prevent tiredness when working (Dictionary.com, 2019). The use of coffee in this context makes the commodity a relatively inexpensive expense when the potential return could be substantial when considered (Zoecklein et al. 2013). Coffee as a commodity is now significantly more widespread than when coffeehouses first came into existence, this has made coffee products cheaper, more affordable and more accessible to the public than it used to be (Sommerfeldt, 1671). With regards to wine production and wine tasting, more and more artisan wines are being produced with unique, avant-garde profiles. This is supported by the techniques within winemaking being well established from millions of years of development and fine-tuning. The new creative generation is building on these traditional techniques to create something new and unique - winemaking as an art (Dictionary.com, 2019). As a result of this, what was seen as relatively elitist in terms of wine and wine tasting, is now much more common and in need of some kind of gentrification once again. However, the methods discussed in this chapter have been either standard method that have the ability to be adjusted in a way to bespeak certain elements of the final product, such as roasting coffee for longer or shorter, or non-standard methods that can be introduced in the process, such as Appassimento. More findings on the comparison of coffee cupping and wine tasting were established by Croijmans and Majid (2016). Based on the findings, the study attracted comparisons drawn by five coffees and the wine experts. The latter identified different flavor profiles such as coffee 4, which was denoted as Brazilian Yellow Bourbon that captured the description of being sweet, chocolate, balanced as well as carrying acidity. The coffee 5 profile was denoted as Costa Rican Villa Sarchi which was defined as having the fruit, sweet as well as acidity. Such findings were not only directed to coffee profiles but also linked to the “Wine Speak” profile. Based on the latter, flavor experts could confidently communicate through the flavors and smells. Both the wine and coffee experts show the same linguistic behaviors while describing the flavors and smells (Carvalho and Spence, 2018). However, differences could still be noted in terms of the language games that surround the two competitive industries. Notably, the wine talk is regarded as an attested genre, which cannot be compared to the low lying coffee talk. This equally implied that wine experts had more to talk, read and listen about the flavors and the wines with pieces of evidence pointing at tastings, menus and even magazines.

However, Croijmans and Majid (2016) also gave a different implication when it came to defining the coffee and wine culture as well as sub culture. Based on the findings, judgment sessions or wine tasting compelled the experts to first take note of the color before detecting the smell of the wine. Smelling falls into two parts where in the first case, the wine is smelled while resting in the glass and secondly, the smell is determined when the wine is swirled to deliberately get rid of any additional aromas. On the other side, flavor appreciation comes in thereafter as experts are compelled to pay attention to how dry or sweet the wine is, and after how long the taste lingers and what mouthfeel can it yield. This is slightly different from the approach adopted by coffee experts (Zoecklein et al. 2013). Coffee judgments are essentially determined through cupping. Similar to wine experts, coffee experts take note of the color. However, the increased attention on coffee profiles makes the coffee experts to divide the smelling component of cupping into three significant parts. First, the freshly dry ground coffee is smelled. This is commonly denoted as the “fragrance of the coffee” (Croijmans and Majid 2016). The second part includes smelling the crust, which is formed after pouring water into the coffee. The aroma of the coffee is equally determined at this point. The final part includes tasting coffee from the spoon as experts pay attention to how sweet the coffee is. Comparison of wine and coffee further indicates that coffee is likely to produce more profiles and flavors when compared to wine due to its broader smelling component, which is divided into three parts while that of wine is divided into two parts only. These findings leave behind the likelihood of dominating coffee profiles as compared to wine profiles (Carvalho and Spence, 2018). Perhaps, it has emerged that coffee has no restrictions with regards to its consumption, which is a different aspect for wine which is selective in terms of the age.

Chapter 3: Findings and Discussion

This chapter covers the final the findings and discussion part of the research. It looks into the key findings that can be extracted from the literature review before driving the research to conclusion. By the end of this chapter, the reader should have a much better understanding of the position held by coffee and wine, their production, similarities and whether coffee is taking a dominant position as compared to wine. The reader should also understand the background and the basis for why the question - ‘will coffee cupping become the new wine tasting?’ - is being asked. So far in chapter one and two, the methods that are used in the production of coffee and how those methods are used to change the final product have been discussed. But what relevance does this have? What is the point? The main outlet for these bespoke coffees is in the specialty coffee industry. From all steps in the production of speciality coffee, the main aim is to create the best coffee possible by utilizing the techniques already discussed in chapter one and two. For a coffee to be classed as specialty coffee, it has to achieve a score of 80+ when tasted by an SCA (Specialty Coffee Association) Certified Coffee Taster. These scores can only be awarded when all elements adhere to the SCA Cupping Protocols. The ethos of specialty coffee is essentially quality over quantity, selling less but better. This new ethos around specialty coffee is supported by a new ethical society. This new society is more interested in where things come from, fair-trade and organic produce. The new interest would translate into an interest in where coffee comes from, which is something that most specialty coffee shops actively promote. A desire for organic and fair-trade produce also provides better quality produce (usually), which is consistent with the ethos of specialty coffee - quality over quantity. It can be argued that organic does not necessarily mean better, as illustrated by Laurence Fillion.

Now, there is a demand for better tasting coffee, it relies on the specialty coffee farmers, roasters and shops to provide the supply as stipulated in the literature review. Most of the studies purported this had a direct effect on coffee tasters and coffee cupping because they are also key elements in the supply of specialty coffee. Because of this, the idea of coffee cupping is being introduced to more and more people, becoming more prominent and well-known to all people regardless of the age. Based on the findings, it can be established that the age coffee is smaller compared to that of wine. However, with such a limited period, Coffee has been able to attract three parts of the smelling component compared to two of the wine’s smelling component. This explains why coffee cupping is attracting over 800 flavors, and still counting, compared to the stagnated 850 flavors of wine. While wine has a history with common habits, Coffee is in itself an evolution that is attracting the new taste and new pleasure in the market. Regardless of the number of flavors, coffee is increasingly attracting attention of the experts attached to food knowledge as they work on the coffee profiles. Based on the findings extracted from systematic review in the second chapter, another idea that could contribute to coffee cupping becoming the new wine tasting is the fact that it is new and intriguing. Similar to wine and wine tasting, there is an elitist perception of those who have a palette that is trained enough to taste coffee properly. Opening coffee cupping to the public will give them an opportunity to feel like they are also one of those elite tasters and give them an opportunity to learn more about coffee. Since its stock market peak in March 2011, coffee as a commodity has been declining, making it more affordable and accessible to more people. This kind of coffee looks like it will follow in the extremely similar steps as wine. This means that coffee is still new and has enormous potential, when compared to wine, to be developed, which could lead to it being as prominent as wine. This newfound potential for development and accessibility, as well as the similarities in production, are the main reasons why I have the option that coffee will follow in the same footstep as wine, and in turn coffee cupping as wine tasting.

Chapter 4: Conclusion

The purpose of this dissertation was to provide context and illustrate some of the reasons why coffee cupping could potentially become the new wine tasting. It did this by firstly giving the reader a general knowledge about coffee and wine, which was then built upon in the later chapters. The final chapter completed the argument by making points that culminated and relied on knowledge from the previous chapters in order to inform the reader’s decision. Chapter one focused on what coffee and wine actually are. It described and illustrated the anatomy of the coffee cherry, most of which has some kind of influence on the final outcome of coffee. It also described the remainder of the coffee and wine production processes which are precursors and evidence to support the idea that coffee cupping will become the new wine tasting. For example, the sugars that develop in the pulp the coffee cherry make the final coffee sweeter and the tannin on grapes makes the wine drier and more astringent, but can help the wine to age. Chapter one also gave a brief explanation of the origin of coffee and its historical position in society - when it was made and drunk as an excuse to socialize and meet other people. Chapter two built upon the foundations set in chapter one and gave the reader a deeper understanding of the production methods in coffee and wine. It did this by detailing how the production techniques discussed in chapter one can be adapted in order to produce different profiles of coffee and wine. For example, if the desired coffee profile is sweeter, it should be grown at higher altitudes in order to engage anaerobic respiration and, in turn, higher sugar levels in the coffee cherry. If the desired profile of a red wine is full-bodied with subtle hints of vanilla and spice, it should be aged in a charred oak barrel for a long period of time (so the tannins have time to mature, making it less dry). Chapter two also gave a brief explanation of how the ideologies of coffee had developed in society - how it was predominantly drank for the caffeine to help people work for longer in order to meet business targets, for example. Chapter two also described how the elitism that once existed around wine and wine tasting has deteriorated due to their techniques being more established. As a result of this, more and more artisan and avant-garde wines have been introduced to the market.

Chapter three introduced the subject of specialty coffee and coffee cupping, which would only be sufficiently understood when familiar with the specialist production techniques discussed in chapters one and two. The evidence that coffee can only be classed as specialty coffee if it achieves a Specialty Coffee Association taste score of 80+, strongly suggests that there can be a similar kind of elitism that used to be present in wine tasting. This new development can be seen as new, intriguing and full of potential for the coffee industry. The strong similarities in the production of coffee and wine that have been discussed in this dissertation, together with their developments in society, strongly suggest that specialty coffee will follow in the elitist footsteps of wine. However, due to coffee being a cheaper commodity, it will open the elitism to a wider audience, meaning its potential could be greater than that of wine. As a result of specialty coffee cupping being new and intriguing compared to the established wine tasting, it strongly suggests that people will cure their curiosity through coffee cupping instead of wine tasting. Thus coffee cupping will become the new wine tasting.

GLOSSARY

Appassimento: A specialist Italian method used within wine making, where the grapes are laid out in the sun to dry, and by doing so the natural sugars are kept and dried which makes the final taste of the wine sweeter overall.

Arabica: A varietal of coffee tree that grows best at higher altitudes and generally produces sweeter fruit compared to Robusta fruit.

Barista: A person that makes coffee.

Bean: The seed of a coffee cherry, the fruit of coffee trees.

Charring: Burning the inside of an oak barrel with fire before ageing wine (or more commonly, whiskey).

Cherry: The fruit of coffee trees, the seed of which is commonly known as a coffee bean.

Coffea: A botanical family of trees that produce coffee cherries.

Coffee: A blanket statement that can be used as a loose description for the commodity during any part of its production, it is only when a specific part of its production is being described that more specific terminology is needed. Coffee is most commonly known as its final product, the drink.

Coffee cupping: Coffee tasting. Professional coffee cupping is carried out by SCA (Specialty Coffee Association) Certified Coffee Tasters, adhering to SCA protocols, to determine if a specific coffee can be classed as a specialty coffee.

Cold soaking: When grape skins are soaked and submerged in cold water to extract the fruit flavours and colour from the grapes without with bitter tannin or engaging the fermentation process.

Destemming: The process whereby stems are removed from the grapes before there are crushed.

Endocarp: The part of the coffee cherry that is made up of three to seven layers of fibrous cells which harden through maturity to provide structure and support.

Endosperm: The main body of the coffee bean that is made up of a number of different soluble and non-soluble chemical compounds, which provides the predecessor for the bean’s final flavour and aroma.

Epicarp: The permeable outer skin of the coffee cherry that provides its colour and allows the fruit to absorb moisture from its surroundings.

Extraction: The process whereby the soluble chemicals in coffee are dissolved into water. The two most common methods are by infusion or percolation.

Green bean: The seed of a coffee cherry after it has been processed, but before it has been roasted. Coffee is usually exported and imported as green beans.

Maceration time: The total time that grape skins are in contact with the juices.

Mesocarp: The slimy, gel-like substance inside the coffee cherry where the fruit’s sugars mix with the water absorbed from its local atmosphere.

Natural: A coffee process where the cherries are spread out in the sun to dry and allow the pericarp to naturally ferment and fall away from the seed. Since natural coffees allow the pulps sugars to caramelise onto the seed, they usually taste sweeter and bolder with flavours profiles of fruit and caramel.

Pericarp: The collective outer part of the coffee cherry, excluding its seed that includes the epicarp (outer skin), mesocarp (gel-like pulp) and endocarp (parchment).

Process: The method of which the seed is removed from the coffee cherry - washed, natural and pulped natural are the most common.

Pump over: A winemaking technique whereby the winemaker mechanically pumps the juice from the tank back into the top of the same tank.

Puck: The compressed coffee grounds held inside the portafilter of an espresso machine.

Punch down: A winemaking technique whereby the winemaker physically punches the skins down underneath the surface in order to mix with the rest of the juice.

Pulped Natural: A coffee process where the cherries are soaked in water and the skins are mechanically removed (similar to if they are being washed), and then the resulting fruit being spread out in the sun to dry. Pulped natural coffees are usually sweet and have body (like natural) but have more acidity from being washed.

Racking: The precess whereby the white grape juice is filtered out of the settling tank, where the juice has been left for enough time for the sediment to settle to the bottom, into a second tank ready for fermentation. However, for red wine making, the initial pulp-skin amalgamation is immediately fermented and then the pressing and racking of red grapes occurs after the fermentation process, but before the wine is aged.

Roasting: The process whereby heat is applied to green coffee beans to cause reactions between chemicals and sugars in each bean. It also caramelises that sugars which contributes to the sweetness of its final flavour.

Robusta: A varietal of coffee tree that grows best at lower altitudes and generally produces more bitter fruit compared to Arabica fruit.

Spermoderm: Also known as the silver skin, it provides protection and structure for the coffee seed, during roasting this skin, or ‘chaff’, sheds and is discarded.

Tannin: Naturally occurring polyphenol compounds found in plants, seeds, bark, wood, leaves and fruit skins. It causes the bitter, astringent and dry tastes of wine as well as helping it to age.

Washed: A coffee process where the cherries are soaked and significantly agitated in water before having the seed removed mechanically. Washed coffees usually taste cleaner and have flavours profiles of nuts and chocolate.

Winery: A place where wine is made after harvest. This is not the same as a vineyard, although there are often wineries on the same plot of land as vineyards.

Yuppie: ‘A young, ambitious, and well-educated city-dweller who has a professional career and an affluent lifestyle.’ (Dictionary.com, 2019)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Fillion, Laurence (2002) Does organic food taste better? A claim substantiation approach. MCB UP Ltd.

Sommerfeldt, Gustav (1671) Virtu del Kafé.

Williams, Brian (2018) The Philosophy of Coffee. The British Library.

Croijmans, I., & Majid, A. (2016). Not all flavor expertise is equal: The language of wine and coffee experts. PLoS One, 11(6), e0155845.

Carvalho, F. M., & Spence, C. (2018). The shape of the cup influences aroma, taste, and hedonic judgements of specialty coffee. Food Quality and Preference, 68, 315-321.

Cotter, W. M., & Valentinsson, M. C. (2018). Bivalent class indexing in the sociolinguistics of specialty coffee talk. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 22(5), 489-515.

Popp, M. A., Bonn, G., Huck, C., & Guggenbichler, W. (2007). U.S. Patent No. 7,244,902. Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

Zoecklein, B., Fugelsang, K. C., Gump, B. H., & Nury, F. S. (2013). Wine analysis and production. Springer Science & Business Media.

Mussatto, S. I., Machado, E. M., Martins, S., & Teixeira, J. A. (2011). Production, composition, and application of coffee and its industrial residues. Food and Bioprocess Technology, 4(5), 661.

Neves, L., Oliveira, R., & Alves, M. M. (2006). Anaerobic co-digestion of coffee waste and sewage sludge. Waste management, 26(2), 176-181.

Iannone, R., Miranda, S., Riemma, S., & De Marco, I. (2016). Improving environmental performances in wine production by a life cycle assessment analysis. Journal of cleaner production, 111, 172-180.

Ubeda, C., Kania-Zelada, I., del Barrio-Galán, R., Medel-Marabolí, M., Gil, M., & Peña-Neira, Á. (2019). Study of the changes in volatile compounds, aroma and sensory attributes during the production process of sparkling wine by traditional method. Food Research International, 119, 554-563.

Da Ros, C., Cavinato, C., Pavan, P., & Bolzonella, D. (2017). Mesophilic and thermophilic anaerobic co-digestion of winery wastewater sludge and wine lees: an integrated approach for sustainable wine production. Journal of environmental management, 203, 745-752.

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts