A Systematic Review of Studies

Abstract

Many military personnel and veterans have been affected and disabled by Post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Consequently, the healthcare fraternity has recommended trauma focused therapies that focus on the traumatic emotions or cognition. The main objective of the current study is to identify effective psychological treatment interventions for PTSD in military veterans. The study searched peer-reviewed journal articles from PUBMED, EBSCO and CINAHL to identify evidence on some of the effective psychological therapies for veteran PTSD. A total of 32 journal articles were included. Cognitive processing therapy (CPT), prolonged exposure therapy and EMDR have been found as the most frequently used therapies for military PTSD. The study has reviewed five RCTs on CPT and four RCTs on prolonged exposure therapy and found a large effect size on CPT with a Cohen d range of 0.78-1.10.The prolonged exposure and CPT has also been found to outperform their respective control conditions (i.e. treatment as usual and waitlist). Specifically, 70% of participants who received prolonged exposure and CPT obtained a clinically significant symptom improvement. However, at least two thirds of patients who received PTSD or prolonged exposure retained their PTSD diagnosis. This study concludes that prolonged exposure and CPT can cause meaningful symptom improvements when used as first line treatments for veterans with PTSD. However, the reviewed studies have indicated high nonresponsive rates, with patients retaining PTSD symptoms. This signifies a need to improve currently existing PTSD treatments and development of newer trauma-focused and non-trauma focused interventions – to improve evidence-based practice.

Introduction

Research shows that there are significant psychological difficulties associated with traumatic experiences such as natural disasters, human-made disasters, road accidents, and military combat (Milliken et al., 2007). According to Tanielian et al. (2008), people living through such experiences may show resilience at the onset of the psychological difficulties, despite also experiencing stress and other symptoms that diminish with time. Furthermore, the Department of Veterans Affairs in North America (2018) observes that some people may even recover from such difficulties without seeking any clinical or psychological help. However, others may develop a variety of psychological challenges associated with trauma. For example, the victims may display phobic symptoms, depressive symptoms, alcoholism, obsessive-compulsive disorder, anxiety disorder, or even conversion reactions (Calhoun & Beckham, 2002). Similarly, individuals with such traumatic experiences may show signs of Acute Stress Disorder (ASD) at the onset or display signs of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

PTSD is one of the most common disorders experienced by victims of trauma and has received significant attention from researchers and literature reviewers. The American Psychological Society (APA 1994) defined PTSD as a syndrome that manifests itself in three main symptoms, namely heightened arousal, repeated experiences of trauma, and reminder avoidance. These symptoms have to be present for three months for a diagnosis of acute PTSD to be achieved (Koven, 2016). The current study focuses on PTSD experienced by war veterans, to explore the evidence that exists for effective interventions for military veterans experiencing PTSD.

Background of the Study

While many veterans finish military conflicts without any visible scars, they may experience many invisible scars that have a lifetime effect. However, regardless of the visibility or invisibility of theses scars, the veterans, their families, communities, and the entire society surrounding them may experience severe repercussions in the aftermath of a war. For instance, the war veterans may experience drug abuse, alcoholism, divorce, unemployment, depression, mental health issues, criminal activity, homelessness or even underemployment as some of the traumatic effects emanating from the military experiences (Bolton et al., 2015). Milliken et al. (2007) & Tanielian et al. (2008), highlight that PTSD and suicide are amongst the most severe consequences that veterans often experience after military service.

Research into PTSD has influenced how the disorder has been conceptualised over time. This in turn has influenced various editions of the diagnostic manuals, both the European International Classification of Diseases (ICD) and the American Diagnostical and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). During the initial formulation of PTSD treatment guidelines, researchers defined traumatic stress as an unusual human experience (Simblett et al., 2017). However, upon recognising the frequency of traumatic events, this definition was revised. The DSM-IV-TR and DSM-IV also set a criterion that an individual had to experience helplessness, horror of intense fear while responding to the trauma to be diagnosed with PTSD. It was later realised that these symptoms were not universal especially among the military personnel (Watkins et al., 2018). Simblett et al (2017) have noted that the developers of the DSM-5 revised the definition of a traumatic event, by defining it as a threat to death, sexual violation, injury, a direct experience of traumatic event, receiving news of traumatic events involving friends or family, or repeated exposure of traumatic events. This implied that the DSM-5 eliminated helplessness, fear, or horror as requirements for the diagnosis of PTSD. The DSM-5 also significantly revised the symptom clusters of PTSD. While there were three symptom clusters (i.e., arousal, numbing and re-experiencing) in the earlier versions of DSM (DSM-III; DSM-IV), the DSM-5 introduced a fourth symptom cluster; thus PTSD was diagnosed based on avoidance, intrusion, negative alteration and reactivity to traumatic events. Ideally, according to Ulmer et al. (2011), the addition of the fourth symptom cluster was occasioned by the split of avoidance into two different clusters, including negative alteration and avoidance in mood and cognition. The negative alteration in cognition and mood includes symptoms that were previously considered as numbing symptoms and persistent states of negative emotions. However, identified changes in reactivity and arousal continued to be symptoms previously thought to be of arousal, as well as self-destructive, reckless, aggressive or irritable behaviour.

With regards to treatment guidelines, various psychological treatments for PTSD have been developed, both trauma-focused and non-trauma focused interventions. Fundamentally, according to Bisson et al. (2007), the former sets of interventions have a direct focus on traumatic memories, feelings, and thoughts. For instance, the intervention might deliver a Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) or Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT) or Prolonged Exposure Therapy (PET). On the other hand, the latter intervention might focus on reducing the PTSD symptoms rather than directly targeting the traumatic memories, feelings, and thoughts. For example, non-trauma focused treatment may include interpersonal therapy or relaxation (Murphy et al., 2009). In the past few years, various research organisations including the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE, 2005), APA (2004), and the Institute for Medicine (2007) have developed various treatment guidelines for PTSD. Some of these guidelines include the American Veterans Health Administration and Department of Defence (VA/DOD) guidelines and the APA guidelines, both of which were published in 2017 (Simblett et al., 2017). While these guidelines are voluminous and may not be expounded herein, the current study may also conduct a review of the methodologies used in some of these guidelines, and then evaluate some of the PTSD treatment interventions recommended by these guidelines for military veterans. To highlight just a few; the APA (2017) approved Fluoxetine, Paroxetine, and Sertraline; even though the current study will only focus on psychological interventions. It is also important to note that these guidelines do not recommend a combination of medication and psychotherapy. In 2017, a new PTSD treatment guideline was published by APA and VA/DoD. These guidelines recommend various treatment options for people with PTSD (Simblett et al., 2017). These guidelines are based on previous systematic reviews and existing research examining various treatment options for PTSD, therefore these treatment guidelines are based on substantial evidence. Notably, while APA guideline is mostly focused on treating PTSD among adults, the VA/DoD provide general recommendations for diagnosis, assessment, treatment, and management of PTSD, especially for use by workers in the DoD and VA (Jonas et al., 2013). According to Jonas et al. (2013), the APA guidelines (APA, 2017) were based on a systematic review conducted at the University of North Carolina by Research Triangle Institute (RTI-UNC EPC) based on the standards for developing high quality, reliable and independent practice guidelines ( Institute of Medicine 2011).. Giving their recommendations on the APA (2017) treatment guidelines, the panel considered various factors, including a comparison between

harms/burdens and benefits of the treatments, the strength of treatment evidence, patient preferences and values, and the applicability of treatment evidence to various populations (Vujanovic et al., 2013). Questions have however been raised on some of the treatment interventions recommended by these guidelines (Simblett et al., 2017). Conversely, the VA/DoD treatment guideline was developed by updating the 2010 PTSD practice guidelines, earlier established by the VA/DoD. The treatment guideline is based on the Guidelines for Guidelines, which is a document that provides internal guidelines on evidence-based practice for use by the VA/DoD Evidence-Based Practice Working Group (2013). According to Karlin et al. (2010), members of the workgroup were professionals with different specialties including behavioural care, ambulatory care, pharmacology, psychology, family medicine, psychiatry, clinical neuropsychology, and pharmacy. According to Karlin et al. (2010), the VA/DoD treatment guideline was based on evidence published between 2009 and 2016. It uses a Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system to evaluate the quality of evidence for purposes of assigning quality grades to each recommendation. Ideally, the GRADE system relies on four essential criteria for assessing the grade of each practice recommendation, including a comparison of both the desirable and undesirable treatment outcomes, patient preferences and values, reliability of evidence quality, and other implications for use such as feasibility and acceptability.

Statement of the Problem

Despite the extensive use of diagnosis and treatment guidelines discussed above, it is essential to reiterate that the guidelines are not standard and are optional. This means that clinicians are at liberty to choose the best treatment guideline on a patient’s case by case basis – in line with the patient-centred approach of care, which requires the development of holistic treatment and care plans based on patient’s specific treatment needs (Karlin et al.,. 2010). This means there is a lack of standardised treatments and a range of treatments are offered to veterans with PTSD. According to Karlin et al. (2010), there is a shortage of research highlighting the best treatment options of PTSD, especially for military veterans.

Research Aim

This study aims to conduct a systematic literature review of psychological treatment interventions for military veterans with PTSD. To identify which treatment interventions for PTSD are the most effective.

Research Question

What are the effective psychological treatment interventions for returning UK military veterans with PTSD?

Justification of the Study

There is still a lack of consensus with regards to who should be offered PTSD treatment, the treatment timing, or mode of intervention. Earlier research (e.g., Brewin 2008, and Bisson 2003) recommend interventions targeted at people at risk of continual psychological deterioration. However, in a further occurrence of a traumatic event, a provision of psychological interventions regardless of the symptoms is more recommendable. Thus, this review seeks to draw evidence from a variety of sources to clarify and establish a consensus on these issues, placed in the context of military veterans.

PTSD has been associated with stress and high economic costs to veterans and their families (Karlin et al. 2010). Therefore, there needs to be effective treatments that would help reduce the burden of treatment. By identifying the most appropriate PTSD treatment interventions for veterans, this study will add to the literature on which interventions are the most effective for veterans experiencing PTSD. It is hoped that this will ensure that effective treatments become readily available for veterans ensuring they receive treatment in a timely manner. The study will provide an evidence-base of treatment options in the treatment selection process, considering the availability of a variety of interventions for PTSD.

Research Methodology

This chapter presents the various methodologies used to collect, analyse, and evaluate data; based on multiple elements of systematic literature review research methodology. Some of the essential items highlighted in this section include the formulation of the research question, online databases, research strategy, and other tools used in conducting the systematic literature review.

The Literature Review Research Methodology

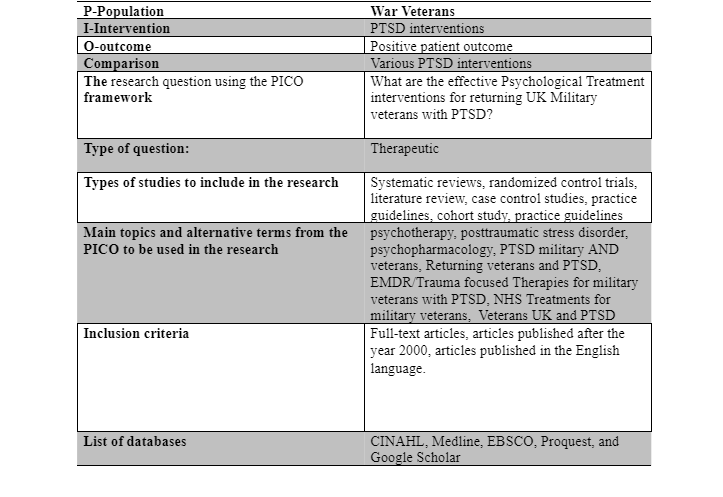

The main focus of the current study is to identify, select, appraise, and review the available evidence on PTSD interventions for military veterans. The entire research process was based on a detailed search strategy to ensure that only quality studies were included for synthesis and further analysis. The systematic literature review methodology was adopted for conducting a critical review of literary sources and identification of relevant evidence-base on the effective PTSD interventions for war veterans. In comparison with other literature review approaches, systematic literature reviews entail the achievement of predefined research objectives through a comprehensive development of research evidence from secondary sources of data (Funk et al., 2010). According to Fink (2014), the process entails a systematic search of literary materials in more advanced and detailed procedure than in other literature review approaches. These reasons justified the selection of systematic literature review as the preferred methodological approach. The researcher developed the conceptual framework of the current study based on the PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison and Outcome) framework illustrated as follows:

The main focus of the research question was on an exploration of various treatment interventions for PTSD for war veterans. The research question was also specifically interested in comparing multiple interventions and suggesting the relatively most effective intervention.

Keywords

According to Bell (2014) Systematic literature reviews are meant to follow specific procedures in search of literary materials and sources of data. According to Fink (2014), part of the procedures is the development of keywords for use in the search process. In the current study, the keywords were developed based on the underlying constructs of the research question. Therefore, some of the keywords considered appropriate for use in the search process included psychotherapy, posttraumatic stress disorder, psychopharmacology. The keywords were used to conduct free searches on each of the selected databases to retrieve the most suitable literary sources for review.

Boolean Operators

The researcher relied on Boolean operators (i.e., AND and OR) to organise the keywords and achieve an easier search process. Mainly, the Boolean operators were used to combine the keywords for purposes of developing precision in the search process, as well as ensuring the specificity of the search process. Hence, the researcher used OR to broaden the search by combining related keywords, while AND was used to connect unrelated keywords as follows: PTSD military AND veterans, Returning veterans AND PTSD, Veterans UK and PTSD.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

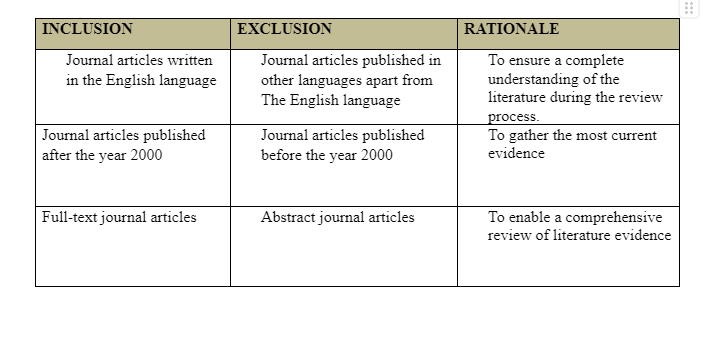

Considering the considerable amount of research that has been conducted on PTSD and interventions for PTSD, the researcher attempted to limit the large number of literary materials to be retrieved through the search process by developing inclusion/exclusion criteria. The criteria were used as guidance to enhance the quality of the literary sources and to reduce the number of selected data sources. The first criterion for inclusion was the year of publication, whereby only studies published after the year 2000 were included in the search. Ideally, the development of PTSD interventions has evolved, and new treatment interventions have been recommended after every ten years (Funk et al., 2010). Hence, studies published before the year 2000 were excluded to ensure that the most current interventions were reviewed. But, the researcher observed an exception to this criterion when there were no publications beyond the year 2000 on EMDR despite being a popular intervention for veteran PTSD. Therefore, in the spirit of evidence-based practice, the researcher included studies published before the year 2000 while reviewing findings on EMDR as a PTSD intervention, as well as landmark studies that play a key role in evidence-based studies but were published before the year 2000. Secondly, because the current study aims to identify and review accurate evidence on PTSD interventions, the researcher will only concentrate on studies that were published in the English language. This will ensure that the review has a complete understanding of the literature during the review process. Thirdly, only studies that could be retrieved in full-texts were included in the review. This is because the reviewer needed to evaluate all the information within the research articles before making any conclusion regarding the most effective PTSD treatment intervention for military veterans. The following table illustrates a summary of the inclusion/exclusion criteria:

Search Strategy

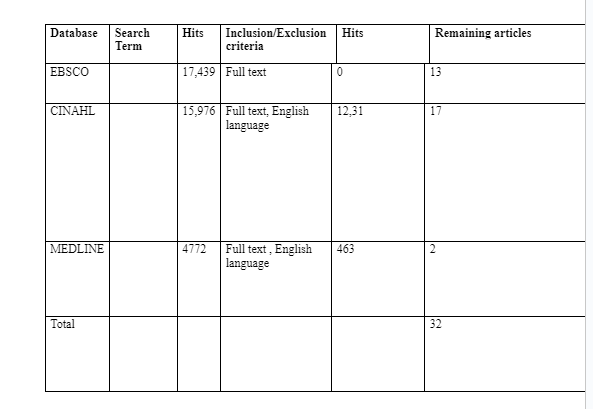

The development of an effective search strategy is vital in the identification of quality and relevant literary sources. Hence the current search strategy begun by a bibliographic search of relevant literature on PTSD interventions for military veterans. The search was selected on major online databases, including CINAHL, Medline, and EBSCO. These databases were selected for use because they allow an easier method of literature collection compared to a physical search in the library (Bell, 2014). Furthermore, it was more feasible to use online databases because the study would be easier to replicate based on a standard search process (Funk et al., 2010). Last but not least, the selected online databases were abundant with quality literary materials on PTSD and its treatment interventions. Meanwhile the entire search process was conducted with the help of both the keywords and the Boolean operators, leading to a retrieval of useful journal articles for review. The following table illustrates the search strategy process with the number of literary materials retrieved from each online database:

Critical Appraisal

Based on the intended quality of the study results, the researcher was determined to include quality evidence for review by establishing a detailed quality appraisal framework for the selected journal articles. Hence, this study used the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) to conduct a critical appraisal of all the selected articles. The CASP is a quality checklist used to ensure that only the highest quality of evidence was reviewed in the study. According to Funk et al. (2010), the CASP checklist comprises of 10 critical questions meant to evaluate the reliability usability and trustworthiness of literary sources for use in a literature review. The ten questions are focused on three main critical issues, namely: what are the results? Are the results reliable? Are the results applicable to the local context?

The journal articles considered as of high quality (YES) were awarded 1 point, while those with unsure quality were awarded 0.5 points. Finally, those with poor quality (NO) were awarded 0 points. Therefore, high-quality papers were those with 9 to 10 points while moderate quality papers were those that could score between 7.5 to 9 points. Low quality journal articles could score below 7.5 points while poor quality journal articles could score less than 6 points. Ultimately, all the selected papers in this study were of moderate quality.

Data Extraction

The researcher developed a data extraction tool aimed at identifying specific information about the selected journal articles. In a process performed by the reviewer, the data extraction entailed an identification of the following information: research aim and objectives, date of the authors’ year of publication, study findings, conclusions and their sample sizes, data analysis, and whether they were prospective or retrospective studies. The extracted data was then compared against each other to identify whether they agree or not. The researcher then applied thematic analysis methodology to develop themes that would then be discussed to yield conclusions.

Findings

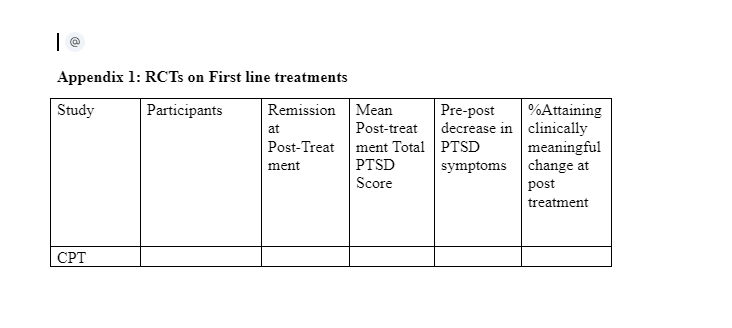

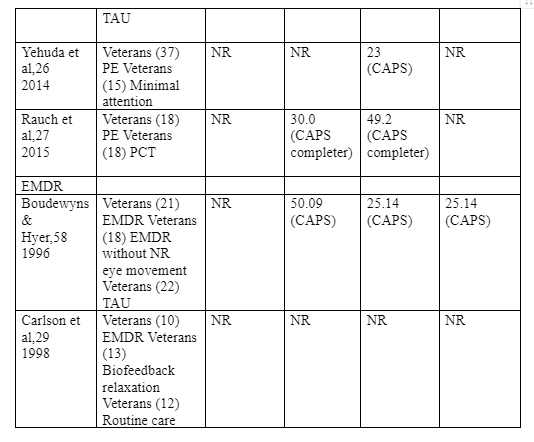

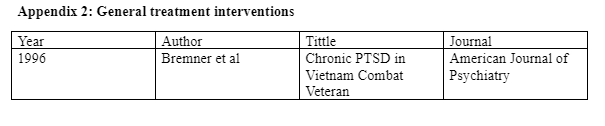

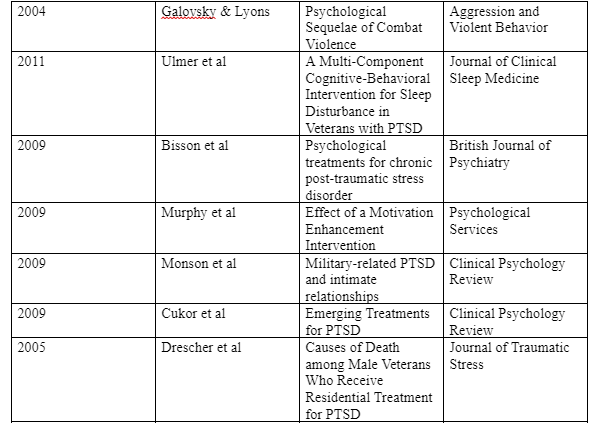

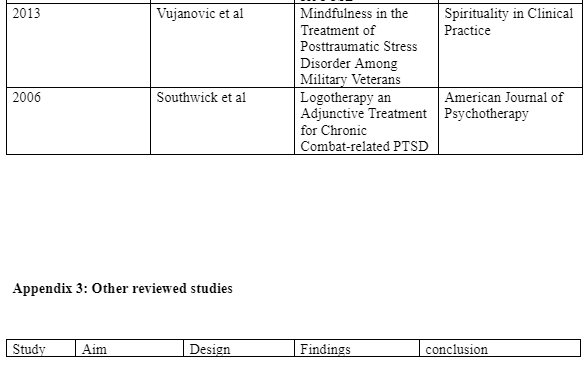

The study retrieved existing journal articles from three major online databases such as EBSCO, MEDLINE and CINAHL. The search strategy yielded a total of 32 studies, 15 of which were classified as first and second line treatment intervention studies, 10 classified as general treatment intervention studies and 7 classified as other reviewed studies (i.e. see Appendices 1,2 and 3). Based in the selection criteria, the selected journal articles were on a variety of PTSD interventions for war veterans and therefore for purposes of an easier analysis, categorised the journals into two major categories, namely those that focused on first and second line treatment of PTSD (i.e., those that have the highest recommendations from treatment guidelines), and those that gave a generally relevant research on military veteran PTSD interventions, treatments, medication and job training. Attached in Appendix 1, are the details for the first category of studies while Appendix 2 highlights the second category of studies. The reviewed studies applied different efficacy criteria. But the most common were effect sizes, average decline in PTSD symptom level in post-treatment follow-up, and level of symptom remission. Other studies also measured the effect sizes based on Cohen d.

Fist Line Treatments

Notably, first line treatments in the reviewed studies were generally categorized as either trauma-focused or non-trauma focused. The trauma-focused treatments included a range of techniques focusing on the details of traumatic experiences or associated emotions (e.g. assumptions and beliefs) through Cognitive-Behavioral approaches. These techniques were Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT), Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing therapy (EMDR), and prolonged exposure therapy (PET); which are also considered the three most widely researched trauma-focused therapies by clinical guidelines (Forbes et al, 2010). It is also important to note that all the three therapies are based on different theoretical underpinnings, require not less than 12-sessions of engagement, require a specialty setting for quality delivery, can be emotionally involving for the patient, and are manualised. Contrastingly, non-trauma-focused therapies aim at addressing the patent’s current stressors, goals, relationships or reactions. Based on the current review of literature, the only non-trauma focused therapy that has attracted a large volume of evidence and supported by a majority of treatment guidelines for PTSD is inoculation training (although this review does not capture any evidence on inoculation training), which entails the development of stress management skills and application of those skills to reminders of traumas and daily stressors. According to (Karlin & Cross, 2014), 98% of veteran affairs institutions in the USA offer both CPT and PET. Interestingly though, the two treatments were not validated for use among active military or veteran population, but rather, there were used as treatment remedies for female sexual assault survivors.

Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT)

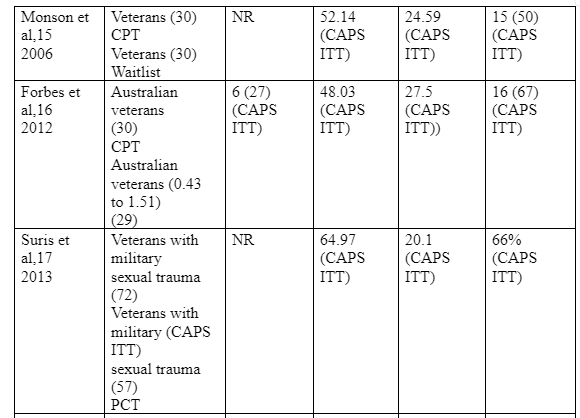

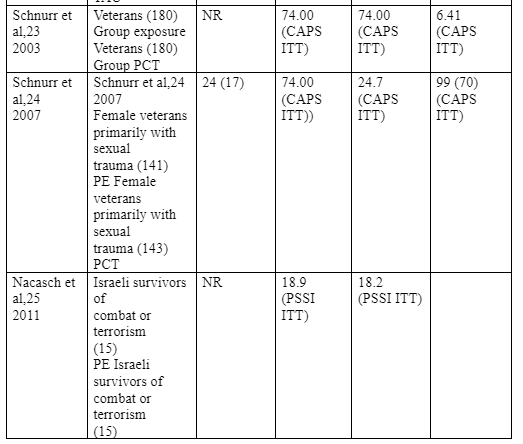

Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT) is a type of cognitive behavioral therapy, but has been found to be more effective for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Resick et al, 2015). It involves teaching the patients how to challenge and modify their beliefs associated with trauma by assisting the patients to understand the traumatic event in order to reduce its ongoing effect on the patient’s life (Forbes et al, 2012). This review identified five randomized control trials on CPT with a total of 481 patients. While four of the trials (Monson et al 2006, Forbes et al 2012, Suris et al 2013, Morland et al 2014) enrolled veterans, one involved active military soldiers (Resick et al 2015). The first trial (Monson et al 2006) entailed a comparison of patient waitlist versus people given either present-centered therapy (i.e. a non-trauma-focused treatment focusing on the patient’s current life problems) or CPT. Also, one trial (Morland et al 2014) compared the efficacy of group CPT delivered through telemedicine and in person., the studies displayed a treatment drop-out rate of between 16% and 35%. Monson et al (2006) involved 30 veterans in the intervention group (CPT) and 30 veterans in the control group (i.e. those who were in the waitlist) both groups had similar follow-up duration (i.e. 1 month). 6 subjects in the intervention group dropped out compared to 4 in the control group. There were no remissions experienced in each group despite a difference in the mean post treatment PTSD score (i.e. 52.14 CAPS ITT core for the CPT group and 76.03 CAPS ITT for the waitlist group). A comparison of the treatment effects between the two groups showed that the TCP group had CPT group had a 24.59 decrease in CAPS ITT compared to 3.07 CAPS ITT for the control group. A comparison of the treatment effects between Monson et al and Morland et al indicated that 50% of the veterans who received CPT attained a clinically significant change in PTSD

symptoms post-treatment while 71% of the CPT group on Morland et al attained a clinically significant change in PTSD symptoms as measured by the CAPD ITT scale. However, it is important to note that Morland et al enrolled different sample sizes; the latter enrolling 30 subjects in the intervention group while the former enrolling 61 subjects in the intervention group. Nonetheless, further comparison between the results of Monson et al and Morland et al indicated that 60% of the intervention group in Monson et al’s study retained PTSD diagnosis at post-treatment while 74% of the intervention group in the study by Morland et al maintained PTSD diagnosis at post-treatment. Hence, despite the difference in sample size, Monson et al realised a larger treatment effect size compared to Morland et al. Three trials (Suris et al 2013, Morland et al 2014, and Resick et al 2015) reported the CPT within group intent-to-treat effect sizes to be d = 1.02, d = 0.78, and d = 1.10 respectively, while all the trials reported a 49% to 67% symptom change as well as meaningful post-treatment PTSD scores that were constantly above the set clinical cutoffs. For example, the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) read 50 on all the trials, while the PTSD Scale-Interview (PSSI) read 20 on all the trials. Furthermore, a post treatment PTSD diagnosis was reported in four of the studies (i.e. Monson et al 2006, Forbes et al 2012, Suris et al 2013, and Morland et al 2014); approximately two thirds of the patients retaining their diagnosis. More importantly, symptom remission was reported in only one trial (Forbes et al, 2010), whereby the CAPS score was less than 20 with a 27% symptom remission, thereby indicating a weak effect. We also had a deeper comparison between Suris et al (2013) and Resick et al (2015) and Forbes et al (2012). Forbes et al involved 30 veterans in the intervention group (CPT) and 29 veterans in the control group (TAU) and both groups had similar follow-up duration (i.e. 3 months), Suris et al 2013 involved 72 veterans in the intervention group (CPT) and 57 veterans in the control

group (TAU) both groups had similar follow-up duration (i.e. 6 months), while Resick et al 2015 involved 56 veterans in the intervention group (CPT-C) and 52 veterans in the control group (CPT) both groups had similar follow-up duration (i.e. 12 months). In Forbes et al, 9 intervention group subjects as well as 9 control group subjects dropped out. Suris et al experienced a 35% drop out in the intervention group and an 18% drop out in the control group. Similarly, Resick et al (2015) experienced a drop out of 27% in the treatment group and 13% drop out in the control group. 27% of the subjects in Forbes et al’s intervention group experience a remission at post-treatment, while only 3% in the control group experienced remission at post-treatment. Both Suris et al (2013) and Resick et al (2015) did not report any treatment remissions in either their treatment or control groups. Regarding the comparison between various control conditions, in the study by Monson et al (2006), the waitlist approaches were outperformed by CPT in regards to PTSD reduced symptom (g = 1.12), significant symptom change, and loss of diagnosis, even though symptom change did not remain statistically significant one month after treatment. Nonetheless, in Monson et al (2006), there was a more significant (d = 0.97) symptom remission and clinical symptom improvement than treatment as usual among Australian Veterans. In Forbes et al (2010), found a non-significant group difference in meaningful symptom improvement and loss of diagnosis at three-month follow-up, although the group differences in symptom remission between CPT and TAU remained significant. Suris et al (2013) compared present centered therapy and CPT as a treatment for military sexual trauma and found a significant (d = 0.85) reduction in PTSD symptoms after treatment in CPT despite the fact that the group differences did not remain significant after 2, 4, and 6-month follow up. Furthermore, the study did not find any significant differences in the PTSD symptoms assessed through interviews. Nonetheless Suris et al (2013)

encountered some fidelity issues whereby one therapist assigned to deliver the CPT had unsatisfactory competence. Consequently, after conducting a supervisory evaluation, the researchers decided to exclude the therapist from the study and avoid the analysis of his data. Ideally, this action was meant to ensure that the data associated with this therapist was not attributed to CPT. In another trial (Resick et al 2015) comparing present centered therapy and CPT in active military soldiers, results showed a statistically significant improvement in self-reported PTSD symptoms in both groups (i.e. CPT and present centered therapy), although the CPT group showed more statistical significance (d = 0.40). Moreover, Resick et al (2015) found small and non-statistically significant between-group differences especially with regards to interviewer-assessed PTSD symptoms immediately after treatment (d = 0.21), six months after treatment (d = 0.22) and 12 months after treatment (d = 0.21) – as discussed further in the following sections. Nonetheless, Resick et al (2015) also found no significant differences in the average number of patients with clinically significant change in self-reported PTSD symptoms immediately after treatment, six months after treatment, and twelve months after treatment. A deeper comparison of the CPT treatment effects between the three studies revealed significant differences that are worth noting. For instance, with regards to change in PTSD symptom at post treatment, 67% of subjects in Forbes et al’s intervention group obtained a clinically meaningful change in PTSD symptom at post treatment, compared to 66% and 49% in Suris et al and Resick et al’s studies respectively. Similarly, when we compared the number of CPT intervention group subjects who retained PTSD diagnosis at post treatment, we found that 63% of the subjects in Forbes et al retained PTSD diagnosis post intervention, compared to 72% in Suris et al and no remission in Resick et al. This implies that regardless of the sample sizes, Forbes et al indicated the largest CPT treatment effect as per CAPS ITT measurements.

In totality, the reviewed randomised control trials on CPT were focused on both the veterans and active military personnel with sexual trauma or combat trauma and have shown an acknowledgeable level of methodological rigor (at least according to the current researcher’s evaluation), even though one trial, Suris et al (2013), had some fidelity problems. Moreover, the reviewed trials had large effect sizes compared to usual treatments or no treatments (waitlist).

Prolonged Exposure Therapy (PET)

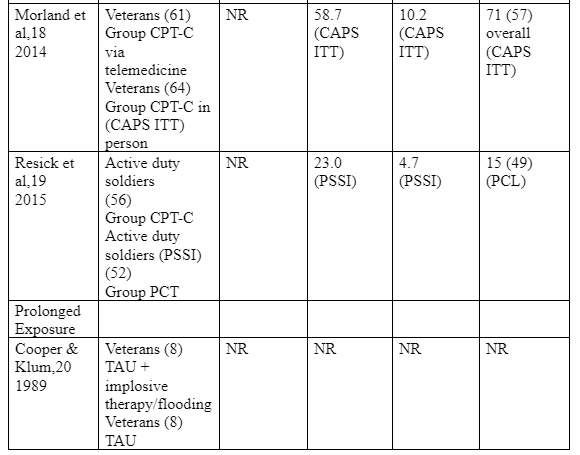

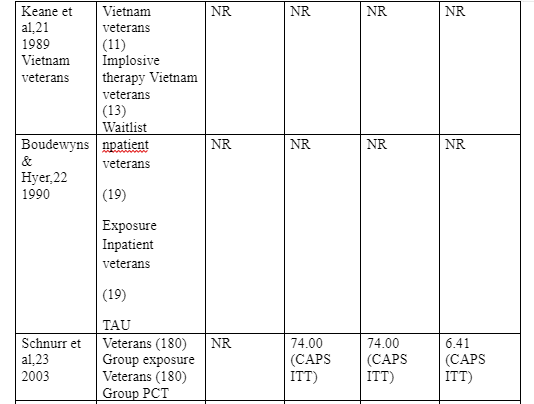

Briefly, prolonged exposure therapy denotes the activity of engaging the patient in a repeated recalling of the trauma to eliminate the fear associated with such traumatic memories (i.e. also called imaginal exposure) and to get used to facing trauma reminders in real world. This differs from CPT which entails cognitive restructuring, whereby the patient is guided through to change the maladaptive beliefs they adopted as a result of exposure to trauma. This may involve writing about of the traumatic experience. Firstly, PET is a type of cognitive behavioral therapy that involves the use of two approaches (i.e. vivo and imaginal exposures) in treating PTSD. According to Rauch et al (2015), the imaginal exposure involves a retelling of the trauma memory, while vivo exposures involve a gradual confrontation of places, things and situations that remind the victim of the trauma. Nonetheless, PET may also involve breathing retaining and trauma memory processing (Schnurr et al, 2007). Four randomised control trials were identified that (i.e. Schnurr et al 2007, Nacasch et al 2011, Yehuda et al 2014, and Rauch et al 2015) focused on PET as a PTSD intervention for military veterans. An analysis of earlier studies (e.g. Cooper et al 1989, Keane et al 1989, and Boudewyns & Hyer 2003) reveals that PET is a new approach and earlier approaches used exposure-based techniques. Also, one of the trials (Schnurr et al 2007) included an exposure-based group therapy that neither yielded a considerable reduction in PTSD symptom nor produced better results than present-centered Therapy (PCT) control group. However, the most robust randomised control trial compared PET with present centered therapy among sexually traumatized veterans (Schnurr et al, 2007). Meanwhile, Yehuda et al (2014) focused on minimal attention, Rauch et al (2015) focused on present-centered therapy, while Rauch et al (2015) focused on treatment as usual. (Yehuda et al 2014 and Rauch et al 2015) were primarily focused on glucocorticoid-based biomarker responses dealing with clinical improvement. Ultimately, the general dropout rates among these studies were 13% to 39%. To achieve a deeper analysis, we compared the studies across different aspects and realised various points of differences in the study sample sizes and treatment outcomes. Schnurr et al enrolled 141 female veterans with sexual trauma in the treatment group (PE) while 143 similar subjects were enrolled in the control group (PCT). Both groups were put under equal follow up duration of 6 months. Nacasch et al 2011 enrolled 15 patients in the intervention group (PE) and 15 subjects in the control group (TAU) both groups subjected to equal follow up duration of 12 months. Yehuda et al (2014) enrolled 37 participants in the intervention group (PE) while 15 veterans were enrolled in the control group (minimal attention), with equal follow-up duration of 3 months. The last study in the group, Rauch et al (2015), involved 18 veterans in the intervention group (PE) and 18 veterans in the control group (PCT) with no follow up duration assigned to each group. Participants in only one study (Schnurr et al) experienced remissions at post treatment (i.e. 17% and 7%) in treatment and control groups respectively. The studies also displayed a difference in mean post treatment total PTSD scores in their intervention groups

indicted as 52.9 (CAPS ITT) 18.9 (PSSI ITT), no remission, and 30 (CAPS completer) in the intervention group among Schnurr et al, Nacasch et al, Yehuda et al, and Rauch et al respectively, while the mean post treatment total PTSD score in the control groups were 60.1 (CAPS ITT), 35.0 (CAPS ITT), no remission, and 53.6 (CAPS completer) reported by the Schnurr et al, Nacasch et al, Yehuda et al, and Rauch et al respectively. There was also a difference in pre-post decrease in PTSD symptoms across the intervention groups in all the studies. For instance, Schnurr et al recorded a 24.7 difference in the CAPS ITT scale, Nacasch et al recorded an 18.2 difference in the PSS ITT scale, and Yehuda et al recorded a 23 difference in the CAPS scale while Rauch et al recorded a 49.2 decrease in the CAPS completer scale. 70% of the intervention group in the study by Schnuur et al attained clinically meaningful PTSD symptom change at post treatment, no clinically meaningful change was reported in the studies by Nasach et al and Yehuda et al, while 91% of the subjects in the study by Rauch et al reported a clinically significant change in PTSD symptoms. Furthermore, participants in the reviewed studies retained PTSD diagnosis. For instance, 61% of the subjects in Schnurr et al retained PTSD diagnosis at post treatment; no remission was experienced in the studies by Nacasch et al and Rauch et al, while 56% of the subjects who received PET retained PTSD diagnosis post-treatment. Therefore, regardless of the sample sizes, Schnuur et al reported the best treatment effect size considering it had the lowest PTSD symptom retention. Only one (Schnurr et al, 2007) study reported a large within group intent to treat effect size (d = 0.80) for prolonged exposure. Also it is only the study by Schnurr et al (2007) that reported a clinically significant reduction in PTSD symptoms – among 70% of the patients, a phenomenon that could be attributable to a larger sample size. Furthermore, two trials (Schnurr et al, 2007; Nacasch et al, 2011) the reported mean post-treatment symptom scores remained or were above

the clinical cutoffs for PTSDT, with Schnurr et al (2007) reporting a 52.9 CASP while Nacasch et al (2011) reporting a PSSI of 18.9. A loss of diagnosis in the intent-to-treat sample was reported in one study (Schnurr et al, 2007), whereby 61% of the patients retained their diagnosis post-treatment. In comparison with control conditions in Schnurr et al (2007), there were improved symptoms observed in female veterans with sexual assault trauma who received present-centered therapy and prolonged exposure therapy, with intent to treat effect size of (d = 0.27) in favor of prolonged exposure. No significant group difference in clinically meaningful improvement was observed, neither was there any observed significant group differences for symptom remission or loss of diagnosis after three or six month follow-up (Schnurr et al, 2007). A greater symptom reduction as a result of prolonged exposure was observed in a sample of Israeli veterans compared to the level of symptom reduction out of psychodynamic therapy and the outcomes maintained throughout a 12 month period of follow up. In the study by Yehuda et al (2014), prolonged exposure did not outperform a 30-minute weekly minimal attention control conducted in conjunction with symptom monitoring phone calls. While a significant improvement was observed in both groups, the groups did not display any significant differences (Yehuda et al, 2014). The last randomized control trial examined cortisol after a prolonged exposure and found no significant differences between present-centered therapy and prolonged exposure in the intent to treat sample with regards to interviewer-assessed PTSD outcomes even though the researcher found significant differences (i.e. d = 1.08 in person-centered therapy compared to d = 3.16 in in prolonged exposure) in favor of prolonged exposure in among participants who completed the study. Generally through, there is a paucity of robust randomize control trials on prolonged exposure therapy as an intervention for PTSD for military veterans compared to CPT with an exception of Schnurr et al (2007). Besides, the

review has observed that most of the UK-based studies have small sample sizes. The only two robust studies with robust data on prolonged exposure therapy for traumatized veterans are Boudewyns & Hyer (1990) and Rauch et al (2015).

Eye Movement and Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR)

EMDR is a form of psychotherapy that involves the patient attending an emotionally disturbing event in brief doses while concurrently focusing on an external stimulus. Hence, when a patient is put under EMDR therapy, they are exposed to sequential doses of lateral eye movements to enable them to facilitate and process traumatic memories and to bring them to adaptive resolution, (Kip et al, 2013). Some randomized control trials on EMDR involve small samples that were either tested 1-3 brief sessions (Rodgers et al 2015, Devilly et al 1998, and Jensen 1994) or involved different comparisons (Pitman et al, 1996). Moreover, a review of the studies reveals that the methodologies they used are inconsistent with the methodologies adopted by the most current trials. Two reviewed studies tested the adequacy of EMDR doses and found that they were associated with large symptom reduction and 78% of participants who completed the doses were no longer fit to be classified as having PTSD diagnosis (Carlson et al, 1998). The performance of EMDR was comparable to variants in which the eye tracking was absent or when compared with actively delivered non-trauma-focused therapy. Maintaining its results to a nine-month period, EMDR outperformed biofeedback-assisted relaxation and wait-listing (i.e. those who had not had any treatment) (Carlson et al, 1998). Generally though, most of the studies evaluating the efficacy of EMDR are civilian, and therefore there is a need for more studies on the military population.

Silver et al (1995) involved a sample of 83 veterans who had received a formal PTSD diagnosis. Participants were non-randomly assigned to each of the four groups whereby the first group received EMDR, second group received relaxation intervention, and third group received Biofeedback while the fourth group acted as control group. The researchers did not clearly indicate the treatment duration as well as the therapist’s level of training, but the treatment was apparently replicable even though they did not apply the standard EMDR protocol i.e. they used a non-standardised self-report problem form to measure outcome. Nonetheless, the non-standardized outcome measurement tools indicated that the participants who received the EMDR intervention had better symptom improvement compared to the control group. Ideally, the EMDR treatment group displayed better results compared to Relaxation intervention (except for the depression variable), and better results compared to the Biofeedback group in all the variables. However, despite the positive results, a worrying limitation of this study is that the participants were not randomly assigned. Besides, the researchers used unknown outcome measurements and the results not having any statistical power. In another randomized control trial by Boudewyns & Hyer (1996), 61 war veterans diagnosed with PTSD were subjected to baseline assessment using War Stress Inventory, DSM-III-defined, and the SCID before being randomly assigned to EMDR and Exposure Interventions, while part of the participants were also assigned to the control group. The researchers did not indicate the therapist’s qualifications despite indicating the exact treatment fidelity. Furthermore, despite being generally replicable, the researchers did not follow the required EMDR standardard EMDR protocol. Furthermore, the researchers attempted to control for confounding factors by excluding patients who had been diagnosed with schizophrenia or organic mental disorder. Using the Impact of events scale (IES ) and the Clinically Administer Post Trauma Scale (CAPS) as

instruments for measuring treatment outcomes and blinding the assessor, the CAPS assessment showed a significant improvement in PTSD symptoms, while IES indicators did not show any treatment effect. However, the qualities of these results are limited by the fact that the researchers failed to include measures of standard deviations, therefore it was impossible to determine the effect sizes. Pitman et al (1996) involved 17 Vietnam War veterans diagnosed with PTSD and randomly assigned them to the two components of EMDR (i.e. eye-movement or fixed eyes) in a series of weekly sessions characterized by alternate components of EMDR each week. The study was characterised by low to moderately accepted treatment fidelity. Besides, whereas the intervention procedure was replicable, the researchers used specific but non-consistent standard of EMDR intervention protocol. There were efforts to control the confounding factors, whereby participants with manic, organic, and psychotic disorders were excluded. A blinded assessor used M-PTSD, CAPS, PTSD Symptom Scale and IES to measure the treatment outcomes. Ultimately, the assessment revealed an average (23%) improvement of PTSD symptoms across all the treatment groups despite the fact that the researchers did not provide any comparison data (i.e. standard deviation, correlations and means) to enable effective corroboration of the data. Moreover, these results were limited by the fact that the researchers presented incomplete data and failed to report treatment adherence. Another study, (Calson et al 1998) involved a sample of 35 war veterans and randomly assigned the participants to EMDR, Biofeedback, and Routine interventions. All the included participants had been diagnosed with PTSD using the DSM-IV-PTSD and the diagnoses were established by reviewing each participant’s medical records. Ideally, of interest to the reviews were M-PTSD, PTSD Symptom scale and CAPS attributable to each participant. Whereas the authors reported

that the involved therapists were trained, details of these trainings were unclear. The study was also characterized by variable treatment fidelity; it was replicable and seemed to have followed the standard EMDR protocol. Unfortunately, the authors did not give clear details of the treatment adherence; neither did they acknowledge taking account of any confounding factors. Nonetheless, Calson et al (1998) used the PTSD Symptom Scale, IES, CAPS and M-PTS to independently assess the treatment effects. Ultimately, all the assessment indicated a significant improvement in PTSD symptoms. Consequently, the authors concluded that EMDR is an effective intervention for PTSD for veterans who experience less threatening levels of stress, and that it can have a positive impact on attrition, thereby contributing to a significant level of cognitive attrition. Nonetheless, these results are limited by the fact that the researchers failed to ascertain the assessors’ reliability, did not give clear details on treatment adherence, and failed to take account of confounding factors. Devilly et al (1998) involved 51 Vietnam War veterans and assigned the first batch of 20 participants to either EMDR or EMDR treatments without the eye movement component (REDDR) using a stratified randomization technique. All the included participants had been diagnosed with PTSD based on the PTSD-I and DSM-III-R defined PTSD. The next 10 participants (control group) were grouped to receive a standard psychiatric support (SPS) and were randomly assigned to receive each of the three conditions. The researchers assessed treatment effects using the M-PTSD, while the therapist was reported to have completed a Level II EMDR training, although it was unclear whether the assessor ha a god training in administering EMDR. Ultimately, there were no statistically significant differences in the conditions as indicated by the M-PTSD. Notably though, after a six-month follow up, the researchers reported further reduction in treatment effects among three veterans who were under

both the REDDR and EMDR conditions. However there are several significant limitations to the study findings including low statistical power, limited details about the assessor, an unclear randomisation strategy and less frequent treatment sessions. In another study by Roodgers et al (1999), 12 Vietnam combat veterans with PTSD diagnosis were randomly assigned to two treatment groups i.e. EMDR an Exposure. There were no reports on the level of therapist training, but the treatment was replicable with no consistent adherence to EMDR treatment standard protocol. Besides, while the treatment adherence was reported to be strong, there were no reports of treatment fidelity. Nevertheless, IES was used to assess the treatment effects, with the participants asked to complete the inventory because it related their experiences of distressing memory. Ultimately, the IES assessment tool indicates an improvement in the conditions on the account of Intrusion subscale, but no improvement was reported on the account of Avoidance subscale.

Second Line Intervention

Due to high drop-out and none-response incidences from first-line therapies, researchers have increasingly focused on examining alternative interventions including various types of cognitive-based therapy (Kent et al 2011, Strachan et al, 2012) or interventions delivered through different modes including web-based content (Litz et al, 2007) and virtual reality (Kent et al 2011 & Strachan et al, 2012). For instance, Kip et al (2013) tested the efficacy of accelerated resolution therapy (i.e. a variant of EMDR) and found large effects compared to an educational control condition (which was similar to wait listing) in veterans with PTSD (d = 1.25). Also, there are other randomized control trials that have also revealed the efficacy of mindfulness-based interventions, attention-based modification (Kuckertz et al, 2014), memory specificity training (Moradi et al, 2014) and mantram repetition (Borman et al 2008, Borman et al 2013). There was better (d = 0.85) efficacy of healing touch therapy compared to usual treatment in the study by (Jain et al, 2012). These findings imply that reduced PTSD symptoms can be achieved with various disparate treatment interventions. Contrastingly, there are treatments that have failed to demonstrate efficacy in veterans including biofeedback, mindfulness-based stress reduction, and relaxation (Lande et al 2010, and Kearney et al, 2013). For instance, Possemato et al (2011) found little meaningful improvement of PTSD symptoms with a 3-session intervention involving writing about combat trauma. Dunn et al (2007) conducted a study on the efficacy of cognitive behavioral group therapy for treating drug dependence and comorbid PTSD, and depression and comorbid PTSD. Results did not reveal any substantial improvement of PTSD symptoms.

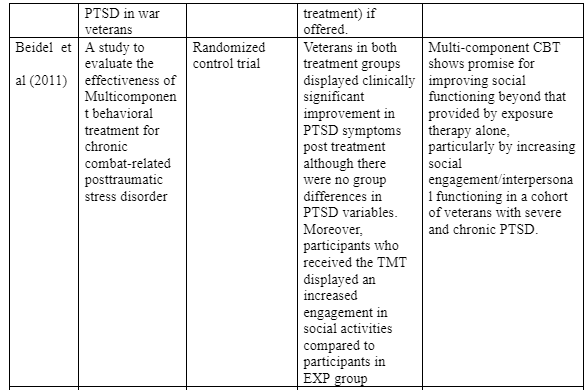

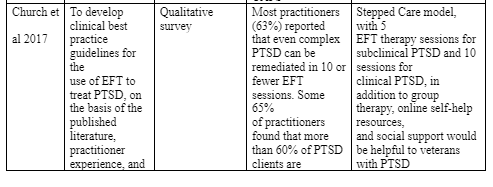

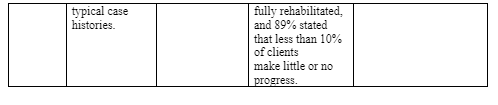

One RCT study (Beidel et al, 2011) evaluated the efficacy of a multicomponent of cognitive behavioral therapy (i.e. trauma management therapy) which is a combination of social emotional therapy and exposure therapy among male veterans with chronic PTSD. The study involved 35 male veterans and assigned each of them to trauma management therapy (TMT) or exposure therapy (EP), after which a clinical assessment was conducted before treatment, during the treatment and after treatment. The results showed PTSD symptom improvement and improved social emotional functioning. Broadly, the authors found that veterans in both treatment groups displayed clinically significant improvement in PTSD symptoms post treatment although there were no group differences in PTSD variables. Moreover, participants who received the TMT displayed an increased engagement in social activities compared to participants in EP group. However, it is important to note that these changes occurred in the period between mid-treatment and post treatment thereby supporting the author’s earlier hypothesis that TMT alone would not contribute to better social functioning. Whereas participants in the TMT group also experienced a significant decrease in physical range, the decrease was particularly experienced upon the introduction of emotional component of TMT. With reference to the many existing evidence on emotional freedom techniques (EFT) as an intervention for PTSD, Church et al (2017) were interested in developing treatment guidelines for the use of emotional freedom techniques, which is a counseling technique consisting of a variety of interventions such as acupuncture, thought field medicine, energy medicine and neurolinguistic therapy, in the treatment of PTSD in war veterans. The study relied on a survey to gather data on the veterans’ experience of PTSD, and used the responses together with existing research evidence to combine a comprehensive PTSD treatment guideline for war veterans. Ultimately, the authors found that even with ten minutes of emotional freedom techniques sessions could remediate complex PTSD symptoms – as reported by 63% of the 448 practitioners. Moreover, 65% of the practitioners who participated in the interviews reported to have achieved full rehabilitation among 60% of the clients while 89% of the practitioners reported that only less than 10% of their clients experienced little or no improvement. Despite not gathering evidence from the therapy recipients, the authors concluded by recommending Five EFT therapy sessions for subclinical PTSD and double that amount for clinical PTSD. One study (Colgan et al, 2016) evaluated the use of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) as an intervention for PTSD in veterans by examining the various components of MBRS that would work well for this particular group of patients. Therefore, the researchers assigned each participant the one component of MBSR i.e. mindful breathing, body scan, quiet sitting and

slow breathing even though the researchers were only interested in evaluating two components (i.e. mindful breathing and body scan) compared to other non-MBSR interventions (TAU). Ultimately, participants who received the MBSR experienced an improvement in depression and PTSD symptoms, while those who received non-MBSR treatments did not experience any depression and PTSD symptom improvement.

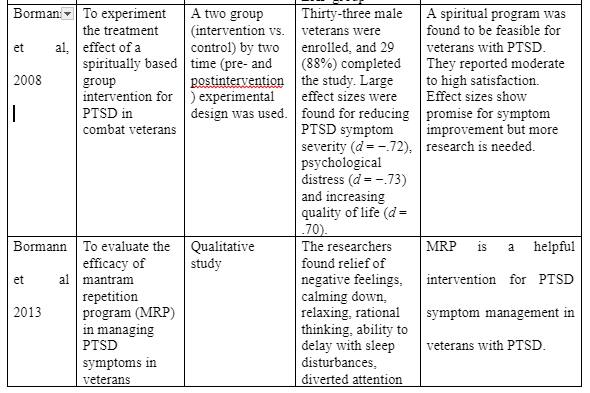

General Treatment and Intervention Studies

Bormann et al (2008) explored the treatment effect of a spiritually based group intervention for PTSD in combat veterans. Specifically, the authors intended to examine the effect size, feasibility, and satisfaction of a spiritual intervention which entailed the practice of repeating specific spiritual phrases on a daily basis to improve PTSD symptoms. A total of 14 veterans (treatment group) were randomly assigned the intervention while 15 participants (control group) were assigned treatment as usual (TAU), and outcome measures were evaluated by quality of life, psychological distress, and patient satisfaction and PTSD symptoms. Based on outcomes from 88% of participants who completed the study the authors found a significant effects size in the reduction of PTSD symptoms. Particularly, psychological distress improved by (d = −.73), quality of life improved by (d = .70), while PTSD symptoms improved by (d = −.73). Therefore, the authors concluded that spiritual programs have a feasibility of being effective treatment for PTSD due to the reported moderate to high patient satisfaction. Because the effect sizes were based on Cohen d, the differences were absolute with no comparing figures for the control group. One qualitative study (Bormann et al 2013) evaluated the efficacy of mantram repetition program (MRP) in managing PTSD symptoms in veterans. The program was delivered on a weekly basis to 65 participants in six sessions, whereby participants were taught how to choose an appropriate

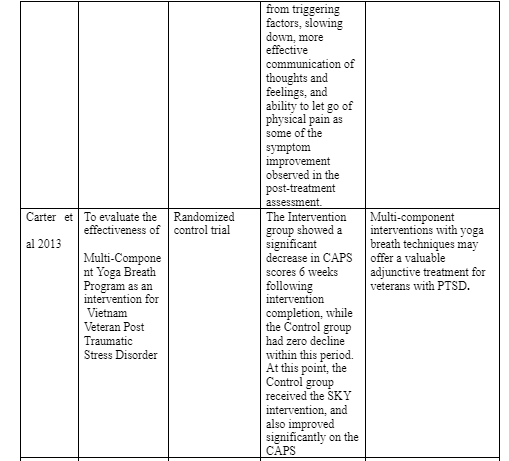

mantram, thoughts and behavioral slow down techniques, as well as emotional regulation. The researchers used the critical incident research design whereby the participants were interviewed three months after the intervention as part of the randomized clinical trial. After collecting data on incident type and frequency, the researchers found relief of negative feelings, calming down, relaxing, rational thinking, ability to delay with sleep disturbances, diverted attention from triggering factors, slowing down, more effective communication of thoughts and feelings, and ability to let go of physical pain as some of the symptom improvement observed in the post-treatment assessment. The authors concluded that MRP is a helpful intervention for PTSD symptom management in veterans with PTSD. Despite the various treatment interventions for PTSD in war veterans, PTSD continues to affect the lives of many war veterans. Whereas many interventions have been developed to manage PTSD, achieving remissions through either pharmacology or psychotherapy has not been easy. Therefore, one study (Carter et al 2013) evaluated the impact of Sudarshan Kriya Yoga (SKY), which is psychophysiological therapy, on sympathetic over activity, parasympathetic activity and stress resilience in patients Vietnam War veterans with PTSD. The intervention was carried out over 5 days with 22 hours of yoga instruction per session. Besides, there was a two-hour group sessions every week in the first month and thereafter 2 hours yoga sessions monthly for five months. After assessing the PTSD symptom severity before the intervention , six weeks after the intervention and six months of follow up, the researchers found a clinically significant improvement in the Clinically Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) among the treatment group six weeks after the end of the intervention while the control group displayed no effects within the same period. Later on, after being exposed to SKY, the control group displayed significant improvement in the CAPS. Furthermore, the CAPS improvements in both groups were

maintained six months after the treatment. The authors concluded that yoga breath techniques have a positive treatment effect on veteran PTSD. The review yielded 10 other general treatment and intervention studies for PTSD in veterans. Bisson et al (2007) was a meta-analysis as opposed to Ulmer et al (2011) and Murphy et al (2009). The main aim of Murphy et al (2009) was to evaluate the level of awareness among veteran PTSD patients and found that veterans may respond poorly to PTSD treatments due to lack of awareness on the need to change as opposed to biological reasons or inadequate interventions. Murphy et al (2009) also argued that veterans with PTSD are likely to see coping strategies such as mistrust of others or social isolation as functional strategies and not as psychiatric symptoms. This implies the need for a focused effort towards the veterans’ readiness to change. In another study by Ulmer et al (2011) on a multi-component cognitive-behavioral intervention for sleep disturbance in veterans with PTSD, it was found that while nightmare problems can be addressed by newly developed interventions, these interventions may not fully address the sleep-related difficulties associated with PTSD in veterans. Three articles were identified that discussed various innovative PTSD treatments for veterans. For instance, Vujanovic et al (2013) evaluated the use of mindfulness-based interventions and concluded that whereas there is an increase in the application of such interventions, there is a need for more scientific studies evaluating their ability to treat psychological problems. In another review by Cukor et al (2009), the authors reviewed the efficacy of pharmacologic and psychotherapeutic interventions for treating PTSD in veterans. After reviewing several studies on social-based interventions as well as other technological interventions, the authors concluded

that emphasis should be put on virtual reality as a treatment intervention for PTSD in veterans (Koven et al). One study reviewed logotherapy as an innovative treatment for PTSD. The treatment involves treatment through meaning, is futuristic and focuses on the individual’s strength while conferring responsibility on the patient to take responsibility and change their situation. Therefore according to Southwick et al (2006), the basic characteristic of logotherapy is infusing optimism on the patient regardless of suffering, also known as ‘tragic optimism.’ Furthermore, tragic optimism takes advantage of the patient’s ability to change suffering into positive achievements and to change from a feeling of guilt to taking actions that will be have a meaningful effect on their lives. According to Southwick et al (2006), logotherapy is an adjunctive therapy that helps in enhancing other PTSD treatments. The authors demonstrate how veterans with PTSD can receive logotherapy in different settings. Ultimately, Southwick et al (2006) conclude that veterans can enhance their lives by engaging in various activities such as volunteerism, service projects, Socratic dialogue and topical discussions. The essence of logotherapy, according to Southwick et al (2006), is that veterans with PTSD can see the condition as a challenge that makes them stronger when they fight its symptoms. The other reviewed journal articles deal with specific problems associated with PTSD. For instance, two studies (Galovsky & Lyons 2004, Monson et al 2009) focus on relationship problems such as divorce, anger and numbing as problems associated with PTSD, and found that addressing these issues can create positive results with PTSD symptoms in veterans. On the other hand, Cukor et al (2009) evaluates the cause of deaths among veterans receiving PTSD treatments. According to Cukor et al (2009), the life expectancy of PTSD patents is often

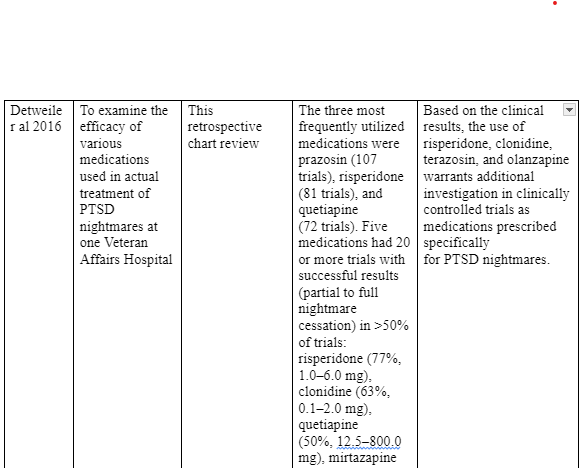

shortened by substance abuse, homicide, and accidents. Nonetheless, the authors fail to comment on the safety qualities of these therapies. Another study, Kearney et al (2011), evaluates the effectiveness of combined treatments mindful-based stress reduction (MBSR) consisting of yoga, body awareness and meditation; and concludes that MBSR can help in achieving significant improvements of PTSD symptoms among war veterans. Foa et al (2005) focuses on three types of treatments for veteran rape victims as well as prolonged exposure. The author asserts that prolonged exposure compared to other techniques, produces better results with PTSD symptoms. But one article, Burke et al (2009), evaluates the important role of independent living, family support, and rehabilitation and provides various resources that can improve PTSD symptoms in veterans. One reviewed study (Detweiler al 2016) specifically focused on PTSD nightmares in war veterans and the various treatment interventions to improve the symptom. The retrogressive chart review evaluated the efficacy and effectiveness of various treatment interventions tested on war veterans in a Veteran Affairs Hospital. The study involved an evaluation of PTSD nightmare treatment records from 2009 to 2013 and compared the efficacy of active treatment interventions used in the patients in comparison with treatment interventions suggested in reviewed articles. Ultimately the study included 327 patients, 13 medication combination and 478 treatment trials. Prazosin, quetiapine, and mirtazapine were the three most frequently used medications appearing in 107, 72 and 81 trials respectively. Five medications featured over 20 trials that yielded either partial or full nightmare cessation. The study concluded that clonidine, olanzapine, and terazosin

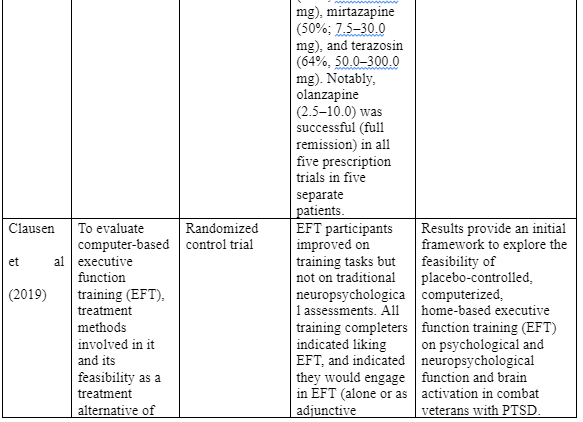

have a good potentiality of treating PTSD nightmare and warrants further research. However, the researchers did not find eny superiority between the dedications and mindfulness based therapy. One recent study (Clausen et al 2019) evaluate computer-based executive function training (EFT), treatment methods involved in it and its feasibility as a treatment alternative of PTSD in war veterans. The study enrolled 20 male veterans with partial or full PTSD and their control counterparts, who were then exposed to functional neuroimaging, neuropsychological and clinical assessments. Both the control group and the assessment group were exposed to EFT for a period of six weeks after which a repeated assessment was carried out to evaluate their dropout rates, and clinical feasibility of EFT. Both treatment groups demonstrated clinically significant PTSD symptom improvement. Moreover, while the treatment group improved in training tasks, they did not demonstrate any improvement in the neuropsychological assessments. Ultimately, the authors concluded that EFT has a potentiality of serving as an alternative treatment intervention for veteran PTSD, even though further research is needed to explore whether EFT may have positive effects above what the study observed.

Discussions

First Line Treatments (CPT and Prolonged Exposure, EMDR)

In the past 10 years, researchers have been interested in establishing effective treatments for PTSD for war veterans and service members. Still, according to findings from the reviewed literature, there is a need for improvement and development of more effective treatments. Nonetheless, some of the most popular first line treatments such as prolonged exposure and CPT have shown large effect sizes within the respective treatment groups. However, it is important to note that effect sizes are not effective in capturing the heterogeneity of patient outcome and are more common with psychology literature than literature in medicine because most psychology literature are based on qualitative feedback. Unfortunately, at most one-half of the patients within the reviewed randomized control trials on prolonged exposure or CPT did not show any clinically significant change in symptoms. Furthermore, in some of the reviewed randomised control trials (Monson et al 2006, Forbes et al 2012, Suris et al 2013, Morland et al 2014), at least two thirds of the patients who received either CPT or prolonged exposure retained their diagnosis after treatment. It is also apparent that within some reviewed RCTs (Monson et al 2006, Forbes et al 2012, Suris et al 2013, Morland et al 2014), the mean scores of PTSD had remained above the thresholds for diagnosis, two studies suggesting that remission is uncommon. More importantly, it was apparent that most trials on prolonged exposure and CPT involved a comparison between patients receiving intervention and those not receiving any form of standard intervention, or with those receiving usual treatment. We also found that when prolonged exposure was compared to CPT, the researchers observed equal improvement levels.

A considerable number of patients in CPT and prolonged exposure trials dropped out, and the rates are similar with the number of dropouts experienced in civilians receiving trauma-focused therapy in (Schottenbauer et al., 2014). Observably, non-adherence to treatment has been a problem among veterans, especially as evidenced in extensive observational studies on military-related DoD and VA treatment interventions, and the studies have found that only a small proportion of military and veteran individuals receive at least the minimum number of mental health treatments upon being diagnosed with PTSD (Hoge et al., 2014). Consequently, Hoge et al. (2014) speculate that these dropouts are attributable to concerns over confidentiality, stigma, time constraints, and lack of proper patient-therapist relationship. Currently, prolonged exposure and CPT remain as treatment choices preferred by VA policies. Besides, clinical guidelines such as the DoD and VA guidelines have recommended prolonged exposure and CPT as treatment interventions for PTSD in veterans US Department of Veterans Affairs (2010), despite being based mainly on civilian participants. Noteworthy though, the guidelines do not give separate recommendations for EMDR and other trauma-focused interventions, thereby treating them with equal standing. However, evidence by Bradley et al. (2005) shows that civilians tend to have better PTSD treatment outcomes than veterans, despite the evidential inconsistencies and lack of enough empirical data to prove this assumption (Watts et al, 2013). Speculations on why treatment outcomes may be better in civilians than veterans are that veterans may have been exposed to more severe trauma and because military personnel is exposed to both life threats and traumatic experiences that may require different approaches to treatment (Price et al. 2013). In a recent study comparing trauma-focused therapy to non-trauma-focused therapy among both civilians and military personnel, it was found that people with more complex trauma such as

refugees and veterans experienced a minimal difference in efficacy between the two therapy approaches, with trauma-focused therapy yielding a moderate distinction in effectiveness among people with less complex trauma (Gerger et al., 2014). However, Gerger et al as not included in the review because it focused on active military personnel rather that war veterans. Other studies have also found additional reasons why veterans might have worse outcomes; including comorbidities, where (Markowitz et al., 2015) found that the 87% of veterans presenting themselves to primary care facilities had at least a comorbidity and three to four disorders. Literature by Hundt et al. (2014) can be used to put these findings into perspective. The authors, while discussing the subject of cognitive behavioral therapy among veterans, observed availability of relatively fewer trials, and that cognitive behavioral therapy often fails to outperform controls, and that these results are unfavorably comparable to civilians. Notably, researchers and practitioners have still not resolved whether focusing on trauma, either through cognitive reframing or through exposure would have treatment effects. Scholars need to reconcile the finding that interpersonal therapy (in civilians) and present-centered therapy may have the same efficacy with that of trauma-focused therapy; with the assumption that sticking to trauma-focused approach can only help in symptom improvement (Markowitz et al., 2015). Various guidelines, including DoD, stipulate that practitioners should be guided by patient preference during treatment selection. But, there is a paucity of research on patient preferences as well as on biological and behavioral influencers of care dropout, which has the most substantial influence on how much treatment can be effective (Hoge et al., 2014). While there are several on-going large scale studies on veteran PTSD and its interventions, it is equally important to research PTSD interventions for military personnel currently in service. Schnurr et al. (2015) conducted a study to compare the effectiveness of prolonged exposure and CPT in veterans. In

that study, it was unclear whether a continued focus on comparing the efficacy of treatments would improve the delivery of care because most leading interventions have consistently demonstrated equivalency in treatment effects among civilians. Similar observations were made by Benish et al. (2008) and Powers et al. (2010). Nonetheless, Schnurr et al 2015 was not included in the review because it could not be retrieved in full text.

Multi-component behavioral therapy

The results of this systematic review have also identified multi-component behavioural therapy as an effective intervention for PTSD in military veterans. The reviewed study (Carter et al 2013), was among the first clinical trials to establish that exposure therapy is effective in managing PTSD symptoms in veterans. It emerged that veterans with EXP and TMT conditions showed statistically significant clinical improvement in PTSD symptoms upon conducting a clinical comparison between their pre and post-treatment conditions. Based on qualitative data from the reviewed studies, this study has found that exposure therapy is associated with reduced nightmares, verbal rage, and flashbacks, even though these outcomes were similar in all relevant treatment groups. However, it is also important to note that the study did not find any statistically significant improvements in the patient’s emotional or social functioning. The results showed that participants in the TMT group experienced an increase in social activities participation as opposed to those in the EXP group. More importantly, it is worth noting that the changes were experienced mid-way the treatment intervention (i.e., after undergoing the exposure therapy), thereby supporting the assumption than TMT can improve the social functioning of military veterans with PTSD. It also emerged from the results that the recipients of multi-component behavioral therapy were associated with reduced episodes of physical rage, although this

improvement was not directly attributable to the SER part of TMT. Worryingly, no participant in the reviewed studies showed an increase in Quality of Life. Nonetheless, this study has established that exposure therapy can benefit veterans with PTSD and confirming the assertions of existing literature that exposure therapy is an effective intervention for veteran PTSD.

Group-based Spiritual Intervention

The literature review highlighted group-based spiritual intervention for veteran PTSD. We encountered data on the feasibility of spiritual interventions and the extent to which patients were satisfied with the intervention. First, the results showed that veterans from different historical wars in Vietnam, fist Gulf and Korea were interested in joining and participating in the intervention. Besides, the researchers did not encounter any difficulty in participant recruitment because most of them were retirees who had the time to participate in such activities. Furthermore, the acceptability of the intervention was depicted in the high retention rates experienced by the researchers. However, it is important to note that the authors had difficulty in recruiting participants from Afghanistan. It is speculated that veterans from Afghanistan could have been more reluctant to participate due to poor timing or mental illness-related stigma. Besides, the reviewed study on spiritual intervention indicated large treatment effect sizes of d −.70, which is relatively comparable to the effect sizes of other established interventions. Generally, this supports the idea that spiritual interventions are an inexpensive and innovative intervention that can be used as complementary to other interventions to improve PTSD symptoms in war veterans. However, the reviewed data did not show a statistically significant effect on clinically measured PTSD symptoms.

Mantram Repetition program

Our results identified yet another PTSD intervention for war veterans called mantram repetition program (MRP). As more veterans return home from war, mental health facilities are tasked to provide quality health services for veterans with PTSD and those with other mental health issues. Furthermore, because mental illness is associated with stigma, it is vital that mental health interventions do not cause further stigma. Moreover, veterans need to be put under mental healthcare as soon as possible to avoid long term PTSD effects. However, it is apparent from the reviewed literature that some veterans may refuse to receive mental healthcare, or may not be ready yet to seek help. Consequently, such circumstances require alternative interventions such as the MRP, which may be valuable in addressing the veterans’ mental health issues. A variety of RCTs have been conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of MRP in treating PTSD symptoms among war veterans and revealing that the intervention can be used as an alternative and yielded similar results. For instance, Bormann et al. (2013) conducted a qualitative study to evaluate the use of MRP by asking the participants about their experience. Among the participants who completed the survey, 92% mentioned that MRP assisted them in managing at least 268 trauma triggering events and enhanced their ability to cope. Furthermore, the study by Bormann et al. (2013) revealed that MRP assisted them in effectively managing symptoms such as sleep disturbances anger, elevated irritability, and releasing emotions. Mantra repetition has also been associated with improved mood and focus of energy, especially considering that PTSD in veterans is characterized by hyperarousal. However, the most intriguing evidence found by this review is that whenever mantram repetition was used, the patient experienced an improvement in PTSD symptoms. The