Association Between Board Composition And College Performance

Opening Statement

The Old Testament prophets did not say ‘Brothers, I want consensus. They said: ‘This is my faith, this is what I passionately believe in. If you believe it too, then come with me’

Reflexive Statement

I have worked in the Further Education (FE) sector as a lecturer within the School of Business and Economics for 20 years and I have held a position as a governor for the previous 12 years.

Following the completion of a Master’s Degree in Finance and a Post Graduate Certificate in Education, I continued to develop my intellectual skills and a PhD in Business and Management seemed an ideal way to do this.

When I took up the role as a governor, I soon found out that there was not enough time to debate issues despite receiving volumes of policy papers usually a month preceding meetings. It became apparent that the entire governing board seemed blocked up with procedures. Senior management (specifically, the principal), was in charge of the governing body and the purpose of the governing board was to rubber stamp the proposals from the senior management of the college.

Prior to taking up this role, I had read and researched extensively on leadership, management organisations and governance within the public sector, specifically within an FE setting including models of leadership which were collaborative and . This led me to formulate my research questions which focused on the association between board composition and college performance including the settings and contexts in which colleges work as organisations.

My consistent study of the literature also has deepened my knowledge and understanding of the sector, however, little understanding of New Public Management has been achieved, because before undertaking this study, I had not completely realised the effects of new public management, even though I was experiencing the phenomenon at governing board meetings. This study has enabled me to take a step back and observe governance as though from an outsider’s perspective. This was useful as it caused me to undertake sefl-reflection and analyse my own practice and role on the governing board from a different viewpoint. Throughout this study, I have become increasingly reflexive about my self-practice and I believe that this has enabled me to make informed judgements and better decisions in my work as a governor.

At the commencement of the thesis my views on board composition, board characteristics and its association with organisational performance were fairly narrow and, I initially held, what I now see, as fairly conventional views. However, after four years and after a considerable amount of research and reflection, I feel I have come a full circle and now I am in a position to begin to answer the questions which I had set out in my application proposal, about how board composition associates with organisational performance.

Chapter 1

1. Background to the Thesis

1.1 Introduction and rationale for the study

The Further Education (FE) sector has undergone major reorganisations since the 1944 Act which brought legal meaning to its existence as successive governments attempted to address the issues of how to drive long term improvements in skills and employment. The 1980s heightened the search for improvements in the sector with numerous pieces of legislations resulting in a situation where providers had been required to cope with endless changes (Jephcote et al, 2008) and perpetually reinvent themselves in the light of the latest concurrent policies. This has been a situation which has been referred to by (Keep, 2006) as policy-makers ‘playing with the biggest train set in the world’.

This constant change in the sector means that leaders and governors face a daunting set of challenges. The Ofsted report on ‘How Colleges Improve’ (2012), sums up the appropriately informed relationships between governors and managers which Ofsted inspectors look for in colleges:

‘The governors of good and outstanding colleges were well-informed, received the accurate information and could thus challenge managers vigorously on the college’s performance.’

A survey of college leaders in 2016 found that creating an agile organisation that is able to anticipate change and react appropriately to it is considered an essential factor in a college’s future success (Feldman, 2016). To this extent, the Leadership Conversation Project undertaken by the Education and Training Foundation (2014) identified a clear sense of urgency about the need to future proof the sector in terms of developing its leaders for a challenging tomorrow. The focus on leaders was concentrated on Principals to the neglect of the governing body. This neglect led me to review the literature pertaining to the roles and responsibilities not only of Principals as in (Leithwood et al, 2004) but also of FE governors as in (Gleeson et al, 2010); and (Cornforth et al, 1999). For instance the Further and Higher Education Act (1992) enabled the Secretary of State to establish a ‘body corporate’ for the purpose of conducting an FE institution. This process, which is typically known as incorporation, created FE corporations. To enact the ‘corporation’, a governing body is formed whose responsibility it is for determining the educational character, mission(purpose) of the college(s), the strategic direction and oversight, the financial health and value for money.

In spite of this responsibility getting placed on the governing boards currently there is still relatively little research available on the association between board characteristics and college performance.

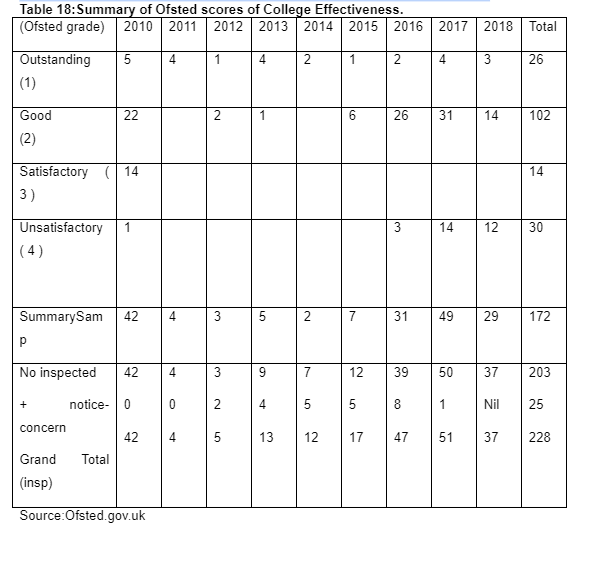

(Cornforth et al, 1999) maintain that the governing board is significant in:

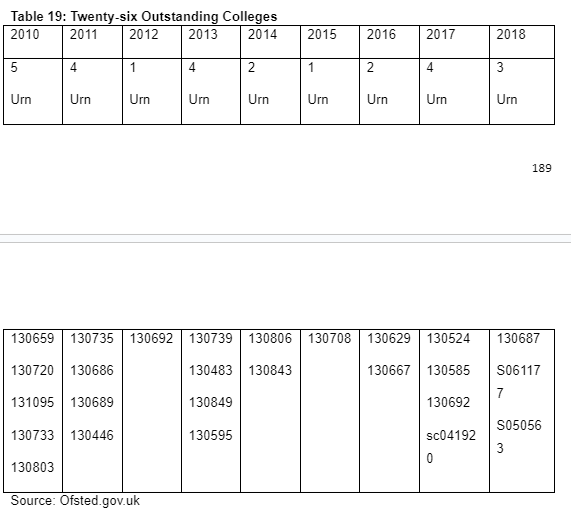

Becoming the point of final accountability for the actions of the college

Becoming the employer of staff

Formulating policy

To understand the role of the governing board in Further Education and the apparent need to set the strategic direction of the college, it is necessary to consider the context and current situation within the sector in a greater detailed manner.

1.2 Contextual setting of the study

The FE sector consists of a diversified range of different providers including general FE colleges and specialist colleges. About four million people participate as students in the sector each year (NAO, 2015). Successive governments have always believed that the sector is crucial to their strategy of raising productivity growth, economic growth and being at par with their European counterparts, a process described as the competitive settlement (Avis, 2007a). It is this settlement that locates the English economy within globalised economic relations which sees its economic success dependent upon making full use of the skills of the labour force. In this settlement, value-added waged labour is seen as the route to a competitive and successful economy, one that is able to ‘hold its own’ on the world stage (Ibid, p:1). Tied to this thinking is the belief that talents of all need to be mobilised and that waste of human potential be avoided. What necessitated this thinking is the situation after the Second World War; a period which saw declining social mobility accompanied by increasing polarities in the distribution of income and wealth.

Therefore FEs focus have always been on providing a link between school and work- supporting people to gain the vocational skills and qualifications they need to secure and to progress in employment or learning (DBIS, 2014). However, this is not their only role as increasing number of FE colleges are now providing Higher Education (HE) courses. In 2012 alone, it was estimated that 250 colleges were providing HE courses to approximately 175,000 students (Parry et al, 2012). The sector however remains the ‘educational Other to schools and universities’ (Page, 2011b) and as the ‘Cinderella’ addition to the framework of the traditional tertiary system (Foster, 2005) in that it sits outside the perceived ‘normal’ progression and is constantly wrestling to maintain a distinct identity. (Foster, 2005), further referred to it as the ‘neglected middle child’ of the British education system located between schools(youngest) and Higher Education (oldest), pointing out that it is often undeservedly neglected in favour of the other two (Ibid). More recently, and perhaps in light of its history, there has been a shift away from the term ‘further education sector’ to the broader ‘learning and skills sector’ to encompass all types of post 16 education.

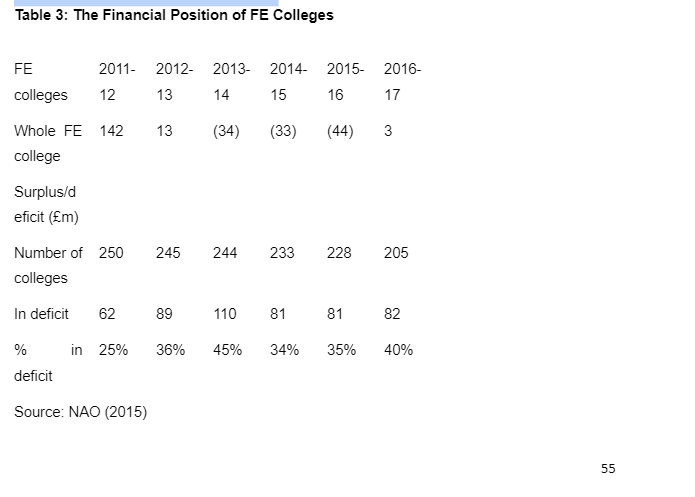

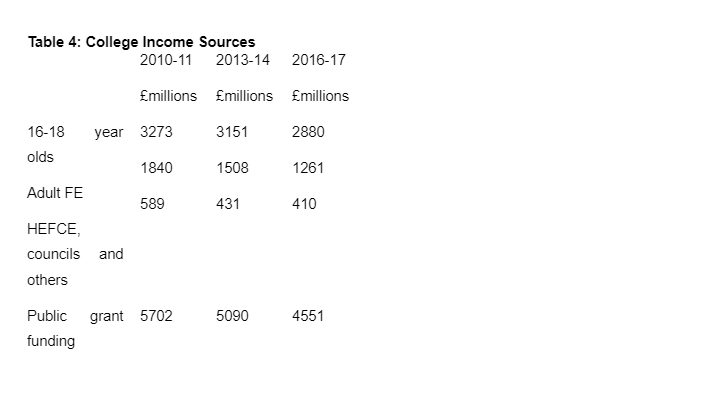

Successive government’s funding cuts have led to the sector facing its biggest challenge for over a decade as budgets are cut and governors are required to manage budgets strictly to according to lender’s specifications to the extent that insolvency is now a crime and governors would be penalised. While there had been a renewed emphasis on the vocational role that FEs face, for example, under New Labour, the entire English education system continues to experience financial problems. Crisis is an over-used word to describe this situation. There is a serious mismatch between expectations, costs and resources. The National Audit Office shows that during the early years of the 2000s, spending on education was 5% of GDP rising to a peak of 5.8% in 2015. It added that the financial health of the sector has been declining since 2010 and almost half of the colleges were in deficit in 2013-14. (NAO, 2015). The report also shows that public spending on education as a share of GDP declined from 4.4% in 2016-17 to 3.9% by 2021-22 (AoC, 2017). The picture overall has been persistent decline in budget based funds allocation from 2010-2015 alone by approximately 25% (Keep, 2014) and it keeps declining. Despite the current interest in high quality technical and professional education from across the political spectrum, the fact remains that the sector is under significant pressures with continuing uncertainties, for example, over the devolution of adult skills funding from 2017. The Skills Funding Agency, responsible for monitoring financial health, anticipates that the number of colleges it rates as financially inadequate will continue to grow. In response to this, the Department for Education working jointly with the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, have launched a programme of post-16 area based reviews to provide opportunities for institutions to restructure their provisions to meet the changing context and so as to achieve maximum impact. The aim is to ensure institutions are financially stable and able to deliver high quality service provisioning, stating ‘we will need to move towards fewer, often larger, more resilient and efficient providers’ (DBIS, 2015b). The 2015-17 Area Based Reviews (ABRs) took place involving England’s further education and sixth form colleges. The ABRs were designed primarily to reduce costs in post-16 education which, under the Coalition and Conservative government, is unprotected in terms of public expenditure. In response to this initiative, colleges will need to review their structures, governance roles and responsibilities to ensure they have the right skills and expertise in place to meet current and future challenges faced by the sector (Justice, 2011). Thus the road to economic stability was identified with creating larger FE institutions or forms of federations which could reduce ‘backroom costs’ and the duplication of provisions. These larger institutional formations were also seen as having the potential to respond with greater effectiveness to needs of the employers on a sub-regional or regional basis and to create higher quality progression routes to employment for young people and adults.

Devolution policies were being developed alongside the ABRs. The Cities and Local Government Devolution Act 2016, was designed to introduce directly elected mayors to combined local authorities in England and Wales and to devolve housing, transport, planning and policing powers to them- a process known as ‘devo-deals’. These include the devolution of the Adult Education Budget and discretionary support for 19+ learners. In essence, while the ABR and the devolution processes could be interpreted as a move towards a more collaborative approach to post- 16 education and training, it was a continued drive in support of the development of a thoroughly market oriented system through support for and promotion of a greater range of providers competing for learners in the post-16 arena. The moves saw the emergence of University Technical Colleges and Academies. These reforms post a completely new set of challenges.

These challenges are many and varied and include ‘significant’, ‘substantial’, ‘simultaneous’ and ‘synergistic’ (Hill et al, 2016,p.79) changes relating to the turbulent nature of the FE sector; the need to secure improvements in learner outcomes and more importantly the cost of resourcing provision. While innovation projects have to focus on the short term benefits, college funding constraints meant they have to seek growth in ways not always central to the needs of the employers. College governing bodies felt that employers do not understand the powerful policy levers that drive college behaviour (funding, inspection, performance), and that employers were only prepared to work with them on short-term initiatives or projects rather than to see them as long-term partners (UCL, 2018). These factors contributed to a lack of mutual understanding between college and local industry. Within the sector, there has been a reduction in standards as judged by Ofsted (Ofsted, 2016). With the number of good and outstanding colleges declining, the imperative was placed on the need to generate and sustain organisational improvement. These combined challenges required governors and principals to demonstrate effective and robust leadership and management skills. (Graystone, 2015, p.26), in a recent review of FE Governance, stated ‘tough times lie ahead for further education’. As a result of these reforms, questions have been raised about how FE colleges can be led, changed and improved within such an unstable environment (Elliot, 2015).

Having briefly considered the wider FE sector to provide background and context specific to the study, I will now present my rationale for the study and contribution to the literature.

1.3 Contribution to the Literature

Improving the effectiveness of colleges is increasingly recognised as a core concern for Governments, however as has been demonstrated above, it is still uncertain whether the reforms have led to improved colleges. This concern has resulted in the plethora of policy and ideological changes that I have recounted in the literature. Central to this concern are the characteristic features which governing boards must possess. While policy and ideological positions change, tensions have continued to manifest in board composition through the discourse of managerialism- a process through which commercial and business values permeate through public sector organisations, eliciting the compliance of new corporate models of managerial control over the work of the governing board. Tensions and mistrust remain unresolved. On the one hand, while managerialism represents the reassertion of ‘management’s right to manage’, (Ball, 1994), on the other, the process conveys the message that efficient management resides in the private, rather than, in the public sector and that outsider board members would infuse market-driven knowledge and discipline into the board and improve college performance.

Despite numerous researches into board composition, none has considered the association between board composition and college effectiveness.

1.4 Research Questions

This thesis investigates the association between governing board composition and college performance. It aims to investigate whether board composition may hinder or improve college performance. By composition, I consider specific board characteristics such as board size, non-executives on the board and executives such as the principal and senior management, the gender of board members and knowledge of the board (finance and education specific).

The study aims to identify whether non-executives (board outsiders) or executives (board insiders) have any significant association with college performance. For college performance, I identify this in terms of the wider sustainable economic, social and environmental benefits that may accrue to a community as a result of college performance. For example, a college’s performance is measured by the number of learners who pass an examination or the numbers who go on to secure employment or indeed the number that progress to higher education.

1.5 Research Questions

1 Is there an association between board characteristics and college (organisational) educational effectiveness?

2 Is there an association between board characteristics and college (organisational) financial health?

3 Do all stakeholders find proper representation (board insider/board outsider) and their knowledge on the governing board maximise college (organisational) effectiveness?

The three research questions are specific and designed to provide an insight into the association between board composition and organisational effectiveness. Effectiveness constructs are defined as goal attainment, constituency satisfaction and resource acquisition (Holland, 1988). It is intended that the research will contribute to the literature on board insider and board outsider theory within further education. It has been informed both by my own experiences and by my reading of the literature. This research is important as many authors believe that FE is a significantly under-researched sector (Gleeson et al, 2005); (James et al, 2007). This current lack of research, specifically within Ofsted observed General Further Education colleges in England, provides originality in this study.

1.6 Structure of the thesis

Chapter one sets the scene by discussing the historical, legal and governance foundations of further education in England. It discusses and assesses the differences between three key stages of development. It introduces government intervention and highlights tensions on governing boards. While the concept of governing boards is increasingly recognised in this chapter, much less is known about the concept and practice of corporate governance.

Chapter two examines corporate governance and the various differences in practice

Chapter three

Chapter four

Chapter five

Chapter six

Chapter seven

Chapter: 2. Literature Review

2.1: Introduction and Overview of Research Plan

The objective of this study is to examine the association between Governing Board composition structure and effectiveness of English Further Education (FE). The focus of the study is on board composition structure, the characteristics which the representativeness that governing bodies are required to have and how all these impact on outcomes which FE colleges must seek to achieve. While doing this, I will examine the history of FE, central government legislations and interventions into FE provision and, if necessary, then design a model that will fill the gap in the literature in respect of fulfilling the objectives of corporate governance in so far as FE outcomes of goal attainment and resource provisioning are concerned.

Given that the existing knowledge is at present limited and often scattered, the scope of this study is substantial and includes the following:

An informed assessment of the composition and role of the Corporate Board.

A review of existing FE corporate governance since 1944.

The role of actors ( Ofsted, FEFC,FE Commissioner Funding Agencies)

The potential for a new model to link board composition, senior management and interested partners in achieving board strategic role and outcomes.

Recommendations. The final goal of the study is to provide stakeholders with the essential knowledge base needed to develop a strategy for effective governance of Further Education provision.

These five components will be informed by a multi-disciplinary perspective and by drawing on observations, questionnaire and interviewing, using qualitative and quantitative research methods. In doing so, the study would be drawing attention to the complex interplay of stakeholder intervention which could underpin FE provision in English colleges.

2.2: A History of Further Education and Governance in the United Kingdom

In order to explore the practice of corporate governance in FE colleges, the analysis reviewed the origins and purpose of FE provision.

In doing this, I have drawn inspiration from McCulloch (2011:254) who suggested that:

'historical research has the capacity to illuminate the past, patterns of continuity and change over time and the origins of current structures and relationships'.

According to Sadler (1908)ⁱ, the view that the state should fix a minimum standard of school training and attainment and require it to be reached by every child was first adopted in England as a principle of public policy in 1876. Sadler claims that the decision to adopt this principle was reached after a conflict of opinion which had lasted for three generations. He opines that it was reached with reluctance. . For scholars like Sadler, voluntary effort has for generations played a great and stimulating part in the social history of English education. He claims that it was this voluntary spirit that gave birth to evening schools and adult school movements which have metamorphosed into further education.

Further Education (FE) is then defined as full-time and part-time education for persons over the statutory school age. It typically includes vocational training as well as academic qualifications. The term FE College is:

'Applied especially to those colleges offering courses at levels equivalent to those of a sixth form, but with emphasis on a wider range of vocational subjects, training programmes and leisure activities'. (Macfarlene, 1990).

Typically, the FE sector provides:

Apprenticeships, which are paid jobs incorporating training that lead to nationally recognised qualifications;

Education and training courses that are provided mainly in a classroom, workshop or via distance learning;

Courses leading to ‘skills for life’ qualifications which are intended to enhance everyday skills in reading, writing, mathematics and communication;

Informal community learning courses for a range of participants (Hill et al, 2015).

The earliest comprehensive picture that I have of governing bodies in England and Wales dates back to the late 1960s (Baron and Howell, 1974) . According to these authors, only half of Local Education Authorities saw governing bodies as significant components in the administration of colleges. They claim that there were three elements which denied governing bodies any significant role. These, according to them, were the emergence of full-time professional staff of education in the local authorities, the political elements of local government and the failure of central government to define a discrete area of responsibility for governors. Arguably, it can be said that as the bureaucratic army of education staff grew through the middle years of the century and as teaching itself attracted all the trappings of a profession, so, any scope for the meaningful participation of 'lay' governors disappeared. Policy-making and the day-to-day running of a college were shared between the Principal and managers.

Indeed, the Taylor Report (DES, 1977b) found:

'Little evidence that, in the standard provision in the 1944 (Act) that the

Governors shall have the general direction of the conduct and

Curriculum of the college' was taken seriously.’

However, the past fifty years have seen a rapid change in the way FE is governed in the United Kingdom. Many changes in various government legislations and rising social aspirations have made the demand for education and governance of further education colleges very challenging. For example, the 1992 Act required governing bodies to:

' ask probing questions, to support the principal, to keep a firm check on senior management, suggest new ways of approaching difficult problems and to draw on its members' own professional experience.' (Shattock, 2000).

With the neo-liberal 'market' philosophy which the 1992 Act brought, the power of LEAs was reduced; the governance character changed almost overnight enabling governors and principals of FE institutions to be accountable to a wide range of audiences, including parents, Local Education Authorities and to the central government. The key questions that emerge in the face of these changes are:

What is corporate governance and what does it seek to achieve in FE? Who are the actors (agents)? To what extent are the interventions in corporate governance defining and adding value to the specific aims of FE provision?

In considering these types of corporate arrangements, the research study examines aspects of corporate governance activities since 1944. In particular, the analysis will identify the effect of changes from activities which tend to define corporate governance as a mechanism for making and implementing collective goals for society, through to an era where they have to be accountable for resources spent and to operate as ‘private’ entities. The research then proposes a model of collaboration to associate non-executive board members as stakeholders in order to maximise board strategic role in the FE sector.

2.3: Historical Context

The latter half of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century saw a period of great change in FE within UK. Particularly, the period between the 1944 Education Act and the Education Act of 1988 were periods of significant experimentation in terms of both the education governance and ideological approaches.

(Hall, 1944) and (Lucas et al, 1999) both claim that the 1944 Act gave birth and legal meaning to Further Education (FE) in the United Kingdom. It was the case that by this time, the United Kingdom was emerging from war time devastation and that the economy needed skilled labour to register growth. However, this critical pool of labour depended upon a sufficient number of trained workers for employers to draw from. As the supply of trained labour was drying up, there was a national concern over skills shortages. Consequently, the then government set up a national enquiry which decided that technical colleges should be the main vehicle to deal with skills shortages. This initiative multiplied the growth of FEs. The penetrating power was so intense that its development can best be summed up in a history of overlapping phases, resulting in a political and national spectrum which reinforced the concept of social democracy (providing education for all). It was this power which ushered in the 1944 Act. For purposes of clarity, I have categorised governance in FE as having gone through three phases: phase 1 (1944-1970s); phase 2 (1970-1980s) and phase 3 (1990s to present).

2.3.1 Phase 1: The Emergence of Governance in Social democracy 1944- 1970

(Gann, 1998) has maintained that the stranglehold that local political parties had over governing bodies, both by their monopoly on appointments and by their control of policy-making, was held on to by local authorities regardless of their political complexion. Governing or managing bodies, as they were called during this era, were squeezed out of their significant roles, sandwiched as they were between the overriding powers of the local education authority and the day to day handling of the college by the Principal.

The broad social and political consensus supported the role of education in enabling economic growth, equality of opportunity and social justice. This move was caused by rising birth rate, economic growth and most importantly the political will to reform. Education policy focused upon the fundamental change of introducing colleges for all young people in place of a tripartite school system practised elsewhere in Europe which selected and excluded the majority of young people. This system of inclusive education growth and governance constituted by the 1944 Education Act was seen by policymakers as providing an appropriate framework to support the growth of a sector committed to the expansion of opportunity. The 1944 Butler Act, which came to be known as the 1944Act, consolidated the stranglehold on the college governing body. By the Act, the Ministry of Education issued Model Instruments and Articles for colleges in 1945. In that instrument, representative governors were to be appointed by the local authority and co-opted. The Articles specified three areas for which the governing body was responsible: the inspection of college premises and keeping the local authority informed of their condition; determining the use of college facilities and appointing the Principal and core staff.

The birth of the 1944 Education Act, made it a legal duty for Local Education Authorities to provide Further Education. It required all LEAs to establish and maintain county colleges which were to provide school leavers with vocational, physical and practical training. The 1944 Act among others stipulated that:

‘It shall be the duty of every local education authority to secure the provision for their area of adequate facilities for further education; including full-time and part-time education for persons over compulsory school age and to serve upon every young person residing in their area who is exempt from compulsory attendance for FE a notice directing him to attend a college. The Act further made it clear that the Ministry of Education was responsible for the payment of any fees incurred in the education of that particular person to the local education authority.’(Act. 1944para. 41-47). Hall,( 1944) explained that prior to the 1944 Act, ‘throughout the United Kingdom, there has never been any legal compulsion on a young person to go to college.’ (ibid p19) He opined that this legal directive to LEAs from central government was necessary. Hall (1944) noted that earlier attempts from central government to enable LEAs to provide education facilities for their local areas had failed because neither any deadline was given to local authorities nor were sufficient funds provided. Although the 1944 Act did not set any specific timetable, as to how and by which date the provisions should be implemented, the LEAs were required to establish and maintain county colleges the purpose of which were to provide school leavers with vocational, physical and practical training. (Lucas et al, 1999) have noted that in the first year after the Act, no extra money was spent on colleges. This neglect, the authors claim, showed the then governments' laissez-faire attitude towards college education funding. In the words of Hall (1944), this laissez-faire attitude was only rectified in England & Wales many years later after the promulgation of the 1944 Education Act. The author admits though that the Act was a ‘great piece of social legislation’ which sought to create educational opportunities for all as it empowered LEAs to serve 'college attendance notices on under-eighteens' requiring them to attend colleges (44-47). Funding for colleges were made available through an amendment to the Act and was administered to colleges by LEAs in the form of grants. LEAs provided grants: for clothing (51), offered boarding accommodation where appropriate (50), provided milk', meals and other refreshment for pupils in attendance at colleges (49) and made grants in respect of medical expenses (100) charging no fees. To give meaning to the 1944 Act, central government further directed that industry does cooperate and associate with new colleges, in order to identify skills gap and for colleges to provide training tailored to meeting these skills. These forms of associations led to the growth of technical colleges which eventually became institutions for 'day release' vocational education of the employed and for those serving apprenticeships. The 1944 Act also created for the first time a Minister for Education, whose role was:

--'to promote the education of the people of England and Wales and to implement the progressive development of institutions devoted to that purpose and to secure the effective execution by local authorities under his control and direction of the national policy.' (Section 1, 1944 Act,) Nevertheless despite the manifest policy of strengthening the central authority, the 1944 Act only provided the Minister with limited and specific powers. For example, the Minister would not control the curriculum nor the teachers, but 'could require LEAs to establish and maintain teacher training colleges '(62).

The post 1944 governing body was in my view an interesting combination of employer and caretaker. The vague definition of duties left the power of managing colleges very much in the hands of the Principal and the LEA. Although the conduct and curriculum of the college was nominally in the hands of governors, any encroachment they might have made into it would be fiercely resisted by the professionals of the college and of those of the LEA. Governors were powerless. Indeed:

'In the London Borough of Haringey in 1979, three governors of Creighton Comprehensive School, including Harry Ree, Professor of Education at the University of York, were removed by the ruling Labour group after they refused to vote in support of a strike of school caretakers. Unfortunately, the party failed to observe such formalities as telling the governors of their dismissal or having the decision ratified by full council. The local government Commissioner said.

‘ It cannot be good administration let alone fair to the individuals concerned to appoint new governors before those they are to replace have been removed from office or even told that they are about to be removed' ( Commission for Local Government,1980)’.

2.3.2 Contradictions in Legitimacy

It would appear that wide powers were given to LEAs. The objective of provisioning such powers was that the LEAs should provide 'adequate facilities' for full-time and 'part-time' education and this practice continued well into the 1960s but some contradictions and conflicts in roles emerged. Under the Act, the LEAs were constituted with wide ranging responsibilities and powers to provide education in order to develop their local colleges and communities. However, just as the Minister of Education was not provided with direct control over the LEAs, the LEAs were deprived of absolute direction of their colleges. The functions and purpose of LEAs managers became too diverse. As a result, what emerged of colleges were a quasi-autonomous status under the general guidance of a governing or managing body which were required to carry on with the business of providing vocational education to cater for the youth. The role of governors was not specified in the Act, except to say that they were mainly co-ordinators of college activities. Hall, (1944)described governors as 'un-elected elites' who performed varying roles; however , as time went on, the concept of governance began to take meaning and purpose. During the latter part of the 1970s, however, there were various attempts to strengthen the position of governing bodies. The Campaign for the Advancement of State Education (CASE) agitated for greater numbers of representative governing bodies, for example in Richmond and in Harrow. The National Association of Governors and Managers (NAGM) emerged as a pressure group and to provide information and training: the first handbook for governors appeared (Burgess and Sofer, 1978); and the Advisory Centre for Education (ACE ) campaign for greater numbers of representative governing bodies emerged. Local campaigns were started for parental representation on school governing bodies. There was also a movement for teacher involvement in school governance based upon some notion of industrial democracy and the rights of teachers as employees to be fully consulted about the aims and organisation of the school (Taylor, 1977). The public inquiry into the events of the William Tyndale Junior and Infants Schools proved to be of major significance. By 1977, there had been some significant progress in the development of governing bodies. But the most powerful voice to emerge in support of governing bodies was the findings of the Taylor Report. This Report, in 1977, was the first review of the structure and operation of school governing bodies and its major recommendation was that governing bodies should be made up of equal numbers of local education authority representatives, school staff, parents and representatives of the local community. But the report also expressed the belief that schools should possess a distinctive character within an efficient system of local administration. The Taylor Committee (DES,1977b) identified five reasons for the increasing demands for involvement in college governance which were made forcefully:

Local government reorganisation in 1974 had increased the size of local education authorities, bringing about a demand for greater involvement in decision-making at the college level.

Reorganization brought together authorities interested in giving a meaningful role to governing bodies with those who were not;

The Advent of corporate management: taking some independence away from LEA Education Departments, raised the profile of governing bodies as a voice for education;

The growth of comprehensive schools awakened public interest in the structures of education.

Voluntary organisations such as CASE; NAGM; ACE brought pressure for change.

The Report recommended representation on governing bodies, in four equal parts, involving the LEA; teaching and non-teaching staff; parents and individuals from the community.

The purpose of governance of colleges at this time meant having a broad responsibility for an organisation, ensuring its survival and its well-being. In the spirit of the Report:

' the new governing bodies would be responsible for establishing the aims of the college, share in the formulation of the curriculum, participate in budgeting, take an equal share with the LEA in appointing the Principal and the primary responsibility for appointing other staff' (Taylor Committee DES, 1977b).

It is worthwhile to note that though the 1980 Act failed to implement the whole-scale changes recommended in the Taylor Report, the momentum for representative governance continued (1992 Cadbury Report; FEFC Guide for Governors 1994; Tricker, 1996) and interest in corporate governance began to gather attention with meaning and purpose.

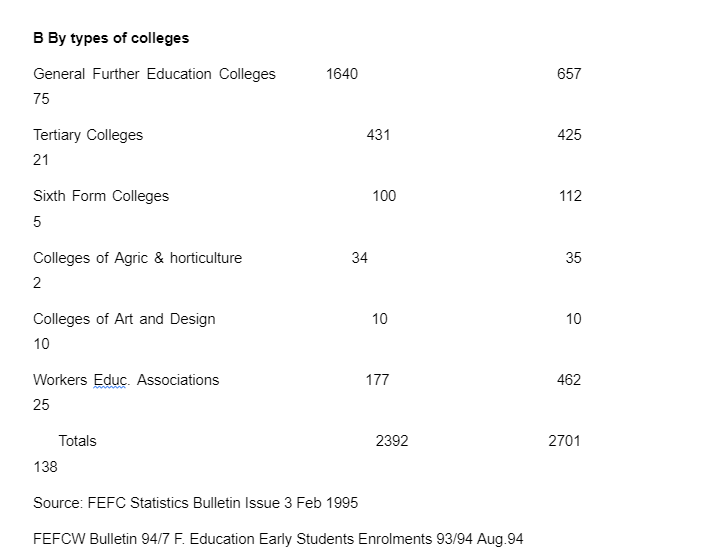

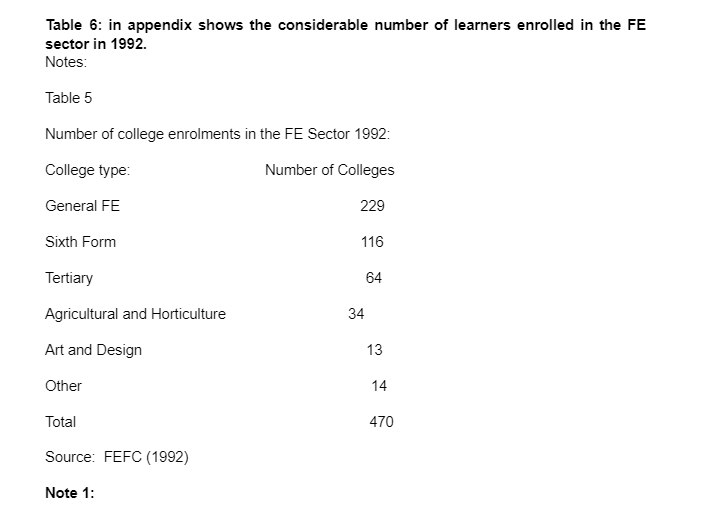

Meanwhile, by the early 1970s, the numbers of young people seeking vocational education provision had grown exponentially. (see table below, student numbers from 1951-1965).

Source: The FE Sector in Context: adapted from' FE and Life-Long Learning Andy Green and Norman Lucas 1999'

(Crowther, 1959) The Government White Paper, (1961) and (Bratchell, 1968), all show that there was greater emphasis on vocational education in the context of apprenticeships; spurred on by the 1944 Act. For example, The Government White Paper, (1961) commenting on Technical Education, announced a new urgency towards vocational education. The paper’s rationale for the adoption of this stand was to make a direct link between the sectors that had skills with those sectors that lacked skills and therefore could not rejuvenate growth. The paper called for increased work in higher technological and advanced technical education. In furtherance of the rationale of it, The White Paper proposed a new Diploma in Technology which led to postgraduate studies. The paper set targets to providers to double day -release students within five years from the existing numbers of 335,000 in 1954. However, these targets 'were not met as even (10) ten years later, those learners on day- release had only risen to 650,000'. (Bratchell, 1968; Lucas,N.& Green,A. 1999). Additionally, in 1959 the Crowther Report remarked that the FE sector’ is a crucial sector for generating economic growth but criticised it for its confusion and proliferation of courses’, and its high part-time attendance and low retention rates. He argued for more day release and sandwich courses. The 1961 Government White Paper, in its maiden release, ‘Better Opportunities in Technical Education', put greater emphasis on lower levels of academic study, but called for a concentration on technicians, craftsmen and operatives. By 1960, the numbers in these categories had risen to 283,000 on part-time or block release courses, 152,000 on evening-only courses, and 14,000 on full-time courses. (Lucas, N.& Green, A. 1999). Again, we observe that between 1960 and 1966, there was significant shift towards full-time, sandwich and day-release courses (Bratchell, 1968). Therefore, it can be argued through these observations that throughout the 1950s and the early 1960s, colleges were seen as responding to government initiatives, reaching a high point of work-relatedness in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Within the period under discussion, apprenticeships remained the main vehicle of vocational training and were usually completed without any parallel off-the job general or technical education.(Bratchell,: 1968).It would appear that, The Crowther Report (1959), which suggested, that, further education would be the next ‘battleground of English education’, had taken momentum with large numbers of young people who had left school at 15 with few or no qualifications signing for college apprenticeships.

There was a further development of interest to the debate here. Within the context of 'Skills for All', the 1964 Industrial Training Act helped to affirm the role of Further Education by providing the training required by apprentices. This Act, established the Industrial Training Boards (ITBs), whose purpose was to promote and coordinate training in the different sectors of the UK economy. The 1964 Act also empowered the ITBs to redistribute the costs of training between employers by means of a levy-grant system; however, as (Field 1996) argued this was found to be ‘too costly for employers’ (Field, 1996).

Meanwhile, as the rush into college apprenticeships were increasing, many school leavers were also opting for college provision in sixth form academic courses. The consequence of this was an expansion in the FE sector which began to expand; it soon earned its name as a sector providing ‘second chance’ education for all (Green 1986:100).

Many academics agree that the focus of FE in the 1960s was influenced by the statutory Industrial Training Boards (ITBs). As (ITBs) were set up to increase skills training in industry and commerce, this move gave meaning and purpose to FE as a skills training provider. (Hall, 1944) argued that many FE colleges were offering courses for unemployed adults and young people who were taking part in government training and employment schemes. This rush into colleges, he claims, necessitated the introduction of a wide range of government schemes including the Youth Training Programmes and Employment Training for adults. The introduction of Youth Training Programmes and Employment Training Programme for adults were given momentum in a 1972 government consultative document ‘Training for the Future’, because of some criticisms of the Industrial Training Act. One major criticism of the Industrial Training Act was the inability of the industrial training board to increase the quantity of industries and to improve the quality of training to meet growing demand. The government, through the document recommended the establishment of a National Training Agency to co-ordinate the work of the industrial training boards and to develop a national training advisory service. (Cantor and Roberts, 1979) argue that it was these recommendations that gave birth to the 1973 Employment and Training Act. The Employment and Training Act, it was observed, ushered in a Manpower Services Commission, which was introduced in 1974, and whose duty it was to promote more and better industrial training. Towards this goal, the Training Services Agency and the Employment Services Agency were established. In 1975, the Training Services Agency, which was renamed the Training Services Division (of the Manpower Services Commission), issued a document called ‘Vocational Preparation of Young People’. This document underlined the serious deficiencies in the existing provision of manpower and ‘suggested appropriate action’ (Cantor & Roberts, 1979: 7). As a consequence of this document, a joint initiative by the Training Services Agency and the Department of Education and Science was launched in order to create a separate vehicle that catered for youngsters in employment not receiving education and training. This special vehicle caused the numbers of trainees to grow by ‘4,500 by the year 1977’ (ibid, 1979:p7).

Another major initiative in Further Education which gave momentum to the rise of FE provision and populism in the 1960s was Technician Education. Technician Education was given priority in the Haslegrave Committee recommendations. The committee which issued its report on Technician Courses and Examinations in 1969, advocated for the introduction of a unified pattern of courses of technical education for technicians in industry and in the field of business and office studies. It was this report that also recommended the establishment of two new councils: - the Technician Education Council (TEC) and the Business Education Council (BEC) to devise and approve an entirely new pattern of courses to cut across advanced and non-advanced further education. According to Cantor & Roberts (1979), the introduction of these two Councils not only increased the number seeking Further Education provision but also increased the variety of courses to include business, art and design education, as industries were more willing to take on people with these qualifications.

However, for all its strengths in providing a legal framework and a focus for Further Education, not seen in the history of UK Further Education provision, the 1944 Act soon came under criticism in the early 1970s. First, the apprenticeship system was seen as deficient and not an adequate vehicle for meeting the skills required by the economy. According to Lucas & Green (1999), the crafts union saw the apprentice system as a means by which the union could protect the skill status of their members. They, therefore (the Crafts Union), restricted trained apprentices entry (from colleges) into their demarcated trades, because, they (the Union) thought that the skills acquired in colleges were not adequate or were too narrow. Employers too viewed the apprentice system as a way of gaining ‘cheap labour' because central government did not place any statutory obligations on them to assist with funding so that the skills acquired will match industry standards’ (Rainbird,1990).

As if these criticisms were not enough, The Carr Report, 1958 also highlighted deficiencies in the apprentice system. According to Carr (1958), the apprentice system involved unduly lengthy periods of time-serving and the system failed to train to any specific standards; provided 'narrow' skills and was 'impoverished' in terms of general education and theory (Carr Report, 1958; Perry,1976 ). (Gleeson & Mardle, 1980), too, were also highly critical of the role of technical colleges. To them the role of technical colleges was to prepare apprentices to fit in with the existing occupational structures and industry status quo so ‘college teachers and administrators did not tolerate questions from learners who genuinely would want to ask questions on industry dominant assumptions such as industry mission and vision, culture and management practices', in relation to the general outlook of the economy. (Gleeson & Mardle 1980) but there was a much more damning observation on governance practices. (Hillier, 2006) argued that the inability of FE governors and the LEAs to coordinate further education activities in the different sectors of the economy was a problem .He contended that as each local education authority was responsible for provision, there were wide variations in the type and amount of technical education available and that because the 1944 Act failed to create a national training system to coordinate the training and accreditation of courses nationally; such absence; of a significant central coordinating body, which would have enabled each LEA to provide education to meet the national needs, only enabled LEAs to focus on provision to meet the required local standards. The result of this failure in the words of (Lucas and Green, 1999), was a 'highly uneven provision' that varied substantially from one locality to another.

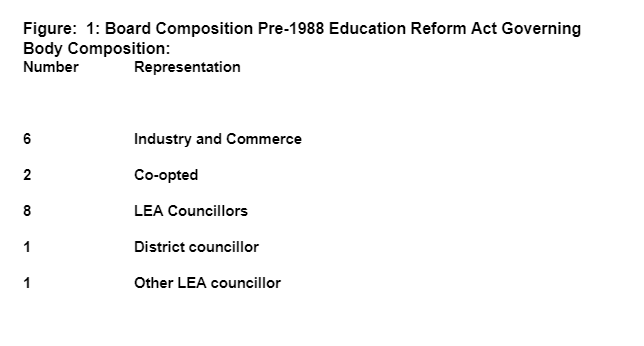

Yet there were more criticisms of the 1944Act. (Gleeson and Mardle, 1980) had earlier observed that legislation under the 1944 Act was permissive, allowing LEAs wide scope for interpretation. As an outcome, there were differences in the courses run by colleges; their grant funding criteria and financial positions at the local level too were different because their geographical circumstances and area populations were different; so too were their management and governance styles (Ibid: 1980:43). The authors remarked that a typical college governing body in the 1960s, would include members appointed by the local authority, representatives of local employers and local trade unions with little or no expertise. In their review of the governing practices of Western College, the authors remarked that the governing board was a 'bureaucratic hierarchy, consisting of conflicting dimensions of FE’: i.e. those with interest in industry and those with interest and skills in education (ibid, 1980:57).

The above criticisms and observations made it difficult for DfE officials at the central government level to monitor progress and to assess the overall impact that colleges and governors were making at the local, regional and national level so as to gauge the overall impact that the entire FE sector was making to the economic development of the nation.

Meanwhile, while the above considerations were being pondered over, attention came to be directed towards an Audit Commission Report on the 'non-performance of colleges and the inefficiencies in the administration of colleges by LEAs. The report was published by the Audit Commission in 1985. This report revealed that LEAs could save the nation fifty million pounds (£50m) a year through better management and organisation (Audit Commission, 1985).For example, in the case of Liverpool City Council, the report found among many others, that, there was a ‘lack of management information, particularly in respect of student hours and lecturing hours,’. The report concluded that without this information, it was difficult to audit the measure of the payments, the reason of such payments and the recipients of such remissions. The observations from the report triggered concerns that information provided to governors could have been improved so that governors are able to make correct assessments and judgements (Frain, 1993) As already observed in earlier pages, the 1944 Act did not specify the role of governors, but left the administration of colleges in the hands of local administrators. The only vague stipulation in the 1944 Act with reference to administration of colleges (and perhaps with misappropriation and conflict resolution), was enshrined in section (68): which said:

'the Minister could intervene to prevent LEAs or managers or governors from acting unreasonably(68). Jones (2003:20) saw this vagueness in the Act and the lack of directives on governor responsibility as sufficient reason to leave the Act for local interpretation, which indeed was the case. Thus, while, for example, in Liverpool, the practice where Liverpool City Council officials gathered four managers of its four colleges at this time, to co-operate with each other, together with a nominated LEA officer to administer policies and to consider issues common to the FE colleges they represented, was highlighted as good practice, this practice of local and regional coordination was not replicated across all LEAs nor County Councils in the UK(Frain, J. 1993).

In considering the deficiencies of the 1944 Act, so far discussed, Lucas and Green (1999) have made the point that the whole arrangements appeared to formulate two separate authorities; - LEAs and Central Government to be in charge of FE, and in not establishing the manner and form in which the governance and the administration of colleges should be performed, the 1944 Act was 'crafted to create confusion'. Specifically, Hill (2014) noted that miscellaneous provisions have been set out in sections: 61-69 including:

-the power of LEAs to conduct or sponsor educational research (82) ;

-the power of LEAs to provide financial assistance to a university to improve further education facilities (84);

-the right of LEAs to accept gifts for educational purposes (85) were too general and lack specificity, and when juxtaposed with sections: 100-107 which said that:

-the power of the Minister to make loans.....in respect of initial expenditure, (105), created confusion in responsibility; seemed to create two separate operational authorities:-, 'dividing the responsibility for the governance of education between central government and LEAs.' (Hill, 2014) .

For these reasons, Hill saw power relations at play in FE provision right from the onset of the government policy: buttressed further in the observation of (Section 1) which said:

-'the Minister had the duty to secure the effective execution by the local authorities, under his control and direction, of the national policy for providing a varied and comprehensive education service in every area' (Section 1 (1)); yet ‘granting autonomy to LEAs to 'set local policies and allocate resources; (41) and to give voice to the corporate spirit and identity of a college'. (Bratchell,1968:65). This author was highly critical of the Acts' position and cautioned that ‘in all these actions LEAs should be wary of their role' because, as he put it:

-'the Minister could intervene to prevent LEAs or managers or governors from acting unreasonably' (68).

This power play, together with the contradictions and confusions in authority, may well have been fuelled in part by the political necessity to impose a succession of different employment training schemes in response to the growing youth unemployment from the 1970s and the plethora of awarding bodies that arose, offering separately developed and differently structured qualifications and courses. Hall (1987) argued that it was in order to overcome this fragmentation, which he described as a ‘jungle of qualifications’ (Hall, 1987), that the then government initiated the review of vocational qualifications in 1985. This review led to the development of the National Vocational Qualification Framework.

Therefore, as a result of the confusion and contradictions discussed which were created by the 1944 Act, responsibility between the key tasks of managing college assets and resources, of planning and of developing curriculum and teaching became blurred. Questions often arose as to who manages what and how. Encompassing the central government, LEAs, colleges, ministers, councillors and teachers. In the words of Weaver, (1976), the 1944 Act created a:

' Complex web of interdependent relationships among the manifold participants'. While the Minister was making 'grants' directly to aided and special agreement colleges for up to fifty (50) percent of the cost of new premises (103), the Minister also had the power to make loans' to aided and special agreement colleges in respect of initial expenditure(105).

Wider afield, the then government had urged the development of technical education at higher levels through the Robbins Report in 1963. The Report, which established polytechnics to work alongside colleges to ensure people gained the necessary high levels of knowledge required for vocational qualifications, was constituted to cause further fragmentation as each qualification had its own awarding body; so for example the advanced further education which was defined as being anything above A level, such as Higher National Diplomas had its own BTEC awarding body.

It is also argued that to a limited extent, the 1944 Act (Part 2) did set out the way in which the building of educational facilities would be carried out and managed by county borough councils, the largest of which was the London County Council (LCC) as one great benefit of the 1944 Act. However, the directive again gave the LCC no power of supervision, control and administration. Rather, these duties were left to the LEAs and the Education Minister to be performed. Another contention for the failure of the 1944 Act was cited: - that the body responsible for the management and administration of educational assets was not clearly laid out by the 1944Act. Hall (1984), also saw ambiguity in governance in the Act but holds the view that FE was constituted in a 'political order of social democracy' based upon the principles of justice and equality of opportunity and designed to ameliorate class disadvantage and class division, and for this reason alone the Act fulfilled a necessary requirement. This political order of social democracy was a result of the immediate experiences from war years of high unemployment and the lack of skilled labour for industry. He claims that it was a period in transition and that the Act provided the plight of the welfare and the lack of work for the citizens more than its legal legitimacy.

Therefore, in all these considerations, it may be right to suggest that the 1944 Act enabled a period of expansion in college education;- providing the needed artisans for industry. Yet in doing so, the FE sector might have failed to achieve anything comparable to the statutory status of schools or universities; nor did it in the words of Lucas & Green, (1999) have 'the benefit of a formalised contractual relationship with employment.' To them, ( Lucas and Green (1999: 23) the 'technical phase' of FE expansion was limited to the expansion of the economy and the development of apprenticeships. They contend that by so doing, the focus of education provision was narrowed down to meeting immediate industry needs; was relatively short -lived and was only confined to the period of the 1950s and into the 1960s. They held the view that vocational education in England was not institutionalized in the same way as it was in other systems in mainland Europe. They cited examples of Sweden and in Germany, where specialised vocational institutions were closely tied to vocational qualifications and the labour market. They support their claim by referring to England in the 1960s where, they claim only a small proportion of 16-19 year olds were involved in full-time or part-time education in relation to the large numbers of the youth population, while the majority of young people in work did not receive any meaningful form of education and training.( ibid: 24).

Considerations of this sort were taken to be evidence of the failure of The 1944 Act and the failure especially of the LEAs to manage FEs in the national interest. These were the considerations which had prompted the conservative government to enact the Education Reform Act (1988) within which the local management of colleges was given critical attention. Considerations of this magnitude led to the second phase of FE development.

2.3.3 Phase 2: -1970s-1980s

We have described some weaknesses in the 1944 Act, however, these weaknesses notwithstanding, interest in FE provisioning has been continuing to expand consistently. According to Hiller (2006), Devon LEA had taken on the challenge of expansion and was the first to establish a tertiary college (ibid:24) in the country. Sixth form colleges, too, were created nationwide , providing full-time education, mainly A level courses for young people moving on from comprehensive schools that did not possess a sixth form. During the 1970s, industry and colleges were to work together to fashion out curriculum and progression strategies. Cantor et al. (1995) argue that it was during the 1970s and onwards that government felt it necessary to intervene directly in education and training policy to grapple with the UK's relatively poor record on skills training. Specifically, during the 1970s, there was growing antipathy in England towards the ‘swollen state’ of the immediate post-war years, largely for economic reasons concerning the level of public expenditure. However, there were complications, misunderstandings and non -cooperation. Complexities of cooperation between industry and vocational skills acquisition notwithstanding, the urge to train the workforce continued well from the 1970s into the 1980s. Full participation in FE was rising steadily and colleges were required to respond with greater effectiveness to the requirements of new types of learners including adults who previously would have gone directly into the industry and also to meet the needs of those learners who wanted to take academic courses such as the Ordinary and Advanced Levels. Many LEAs attempted to establish cooperation between schools and sixth form consortia in order to offer reasonable range of academic courses. Other LEAs removed sixth forms from schools and merged them into sixth form colleges or combined sixth forms with FE colleges to form tertiary colleges which provided both academic and vocational courses. Some tertiary colleges included adult education, whereas other LEAs maintained separate adult provision.

In 1981, the government published a White Paper, 'A New Training Initiative: Programme for Action,' which set out a programme for improving training, including the creation of industry standards. The idea of the White Paper was to try and specify outcomes which would be obtained from vocational qualifications. A further White Paper, 'Working Together: Education and Training' (1986) reinforced the governments' aim to establish standards of competence. One of the recommendations was to set a National Council for Vocational Qualifications; hence it is only proper to identify the period 1970s to 1980s as a period of critical state interventions in FE college provision. While the government was focusing on the creation of industry standards and a system of vocational qualifications, the FE colleges were finding themselves experiencing the requirement to change fundamentally the way in which they taught vocational programmes; their focus was now on how to get their courses recognised by professional associations. FEs were also coming under the requirement to adapt their management styles to industry standards by adopting value for money standards through progression of learners into industry.

As if this change was not destabilising enough to complicate issues of governance, the Education Reform Act of 1988 introduced yet a new form of management and governance. Under this Act, LEAs were no longer in control of colleges in terms of managing their grants and day to day governance as administrators as was the case in the 1944 Act. The new Act of 1988 required that any college with more than two hundred (200) full-time equivalent enrolments could receive funding direct from central government through one of its quangos: - the Skills Funding Agency or the Further Education Funding Council.

The issue of stakeholder governance too continued to dominate the agenda of college administration. A radical response from the government came with the Green Paper ‘Parental Influence at School (1984). This Paper advanced a comparatively greater substantial representation on school governing bodies and some clarification of the governors’ role to enable their more effective functioning. Governing bodies were to exercise far stronger powers in the determination of the curriculum, principles of discipline and the appointment of staff. The report indicated that governors would meet at least four times a year to fulfil these responsibilities.

It was clear by this era that the policies affecting the FE sector were exerting effective control, on the one hand through regulating management and governance and on the other, by defining the type of training and qualifications that the sector provided.

This was the era sometimes referred to as the ‘new era of Vocationalism' because it emphasised the preparation of young people for work. This development was different from that of the 1944 Act period because it shifted away from the narrowly focused 'preparation for work’ towards a wider notion of preparation 'for life', for 'citizenship', 'for multi-skilled work' and for 'collaborative work relationships'. The growth is evidenced clearly as by November 1970, there were six hundred and sixty (660) institutions in the United Kingdom consisting of universities, polytechnics, colleges, day release colleges only; evening institutes, craft institutes and agricultural institutes. (Cantor & Roberts, 1972:p38),the 'purpose of which was to meet the rapidly mounting demand for higher education within further education without prejudicing opportunities for the very large numbers of students following non-advanced courses and to make more rational and effective use of resources available' (ibid: 32). Evening Institutes were expanded in 1970 to six thousand five hundred (6,500).((Ibid:p43)), to cater for large numbers seeking work and for apprenticeship programmes.

By this time, the importance of the further education sector has continued to be recognised through a range of reports and texts, however, one of the most seminal reports that influenced the direction of further education provision was provided by Sir Andrew Foster who led an investigation in the future of further education colleges during 2004-2005. In his report (Foster, 2005), identified a range of strengths within the further education sector, particularly the numbers of learners who accessed learning programmes through college provision. He recognised and acknowledged the wide diversity of provision, evidencing a strong commitment to social inclusion by providers who offered programmes that were both flexible and adaptable. There was also evidence of college provision supporting local businesses by providing programmes that included the skills needed for those businesses. Foster also acknowledged the commitment of further education colleges to develop a professional and committed workforce. However, Foster also identified key challenges: ‘above all, FE lacks a clearly recognised and shared core purpose’ (DfES, 2005).

The Foster Report was followed by another major review by Alison Wolf because although there was an increase in the uptake of education; the technical and practical skills which were imparted were unsatisfactory in meeting the needs of industry and manufacturing. The purpose of her review was to consider how the UK can improve vocational education for 14-19 year olds and thereby promote successful progression into the labour market and into higher level education and training routes. According to Professor Wolf, the UK college education needed a wholesale re-alignment of incentives. She argued that the existing performance tables, funding systems and regulatory compliance were all pushing education and governance in the wrong direction. For example, her view was that 16-19 year olds were discouraged from catching up with their English and Maths through the implementation of league tables. Her view was that current college education was churning 16-19 year olds who meander between education and vocational short-term employment, with a hope to making real chance for progress, or a permanent job, but are finding neither. She (Wolf, 2011), concluded that the framework of vocational qualifications required reform in order to ensure that all those participating in such programmes were given a fair chance of receiving a good education and also be well positioned to obtain a good job. As part of this reform, she identified that all vocational programmes for the future should require all participants to achieve at least a grade ‘C’ in English and Mathematics. In contradiction of the previously developed Diplomas, Wolf argued that young people aged 14-16 should continue to spend the majority of the time focusing their studies on a shared academic core of subjects, rather than any study that might be regarded as vocational.

According to the Wolf Report, another challenge that education providers face is funding. For example the Education Maintenance Allowance (EMA) was a means-tested grant that was offered to learners whose household income fell below a certain level. There were three levels of Education Maintenance Allowance, with students receiving £10; £20; or £30 per week to support them with their travel costs and living costs while attending college. However, there were requirements imposed on students who were in receipt of this benefit. Students were required to provide evidence of attendance at their learning programmes by registering at each class- should they fail to attend any of their lectures, punitive measures would result in terms of withdrawal of the allowance.

With the coming into power of the coalition government, the EMA was replaced with a smaller, new grant. This grant was administered by local providers to those learners considered to be most in need of financial assistance. This scheme was made up of two parts:

- The first part consisted of students who were identified as most vulnerable and received bursaries of (one thousand two hundred pounds) £1200 per academic year

- The second part was discretionary and only awarded to students who were facing genuine financial hardships and to be used on items such as transport cost.

Wolf observed that funding was driven by a government agenda and influenced by a grand market – driven mechanism. The funding architecture was relocated to the Skills Funding Agency, a government quango. This quango was directed by central government to fund particular curriculum areas which, according to policy-makers inform, the construction of an economically active and socially just society. The result is that the funding formula for FE provision follows several funding formulas that allocate money in quite different ways. In practice this means that there are very different sets of principles underpinning each of the funding systems. In keeping with the legal requirement that 16-18-year-olds are enrolled in education or training, the 16-19 Funding Formula functions in a similar way to the National Funding Formula for schools, where qualifications are delivered at no cost to the learner and institutions are reimbursed based on a central government estimate of how expensive such services ought to be to be provided to the students. The Adult Education Budget (AEB) is more closely aligned with the 16-19 years vocational education Funding Formula, but with the important difference that some learners-primarily those aged 24 or older who are in work or not seeking a job- are expected to co-fund their qualifications. These students pay 50% of the agreed rate for their course. However, the ‘agreed rate’ is still set by the government based on the number of learning hours in the course, which are in turn regulated by the Office of Qualifications and Examinations Regulation (Ofqual).

With such a confused signal of provision in the sector, the Wolf review proposed a fundamental simplification of the educational system for 14-19year olds. It proposed major changes in FE organisation and funding, its regulatory structures and its quality assurance mechanisms. The proposals were intended to give institutions the flexibility to respond to local and changing labour markets; and engage employers more directly in delivery and the promotion of quality assurance; give colleges greater access to vocational professionals, and young people greater access to specialized instruction. But more importantly, the review brought more coherence in programme delivery and instruction, a simplified funding system a competitive labour force and high returns to apprenticeship and employment, based on its observation that the many vocational qualifications taken by young people were of little economic value and were generated by governments desire for young people to acquire extensive qualifications with a high chance of success. The legacy of the Wolf Review is that it instead proposed a greater focus on GCSEs-English and Maths in particular- and a move from funding individual qualifications to funding individual students. The government implemented many of these reforms by 2013, including the new 16-19 National Funding Formula and the English and Maths funding condition. Table two shows major reform to further education and skills since 2000.

Table 2: Major Reforms to FE since 2000

2.3.4 Further Education for students with 19 years and more of age

In addition to providing education for young people, the further education sector also provides education and training for adults, which has historically been the main focus of this sector. Extensive ranges of education and training options are available at this stage and are currently providing a comprehensive summary of them is beyond the scope of this study.

Thus, concerning the limitations of the1944 Act, including the inability of LEAs to manage FEs effectively and more importantly, regarding ability of FEs to bring the UK out of recession, the reforms highlighted by Foster and Wolf reports pave the way to a major shift in government policy. However, as the reader will observe, further renewed focus on employability and skills provision by the government led to charges by (Bryan, 2007) of ‘the McDonaldalization of further education’: with charges laid against further education that government messages were so confused that they (the government) did not know what it was that they should be producing. They claimed that further education should be an area that focused on the development of skills, confidence, self-esteem and social inclusion rather than ‘an education’.

There were also resentments which were echoed vociferously by Lord Callaghan. In his famous 1976 Ruskin College speech as the Prime Minister in office, he voiced fears about the quality and governance of education.

Callaghan identified the teaching profession as:

‘Complacent and failing to pay sufficient attention to skills and attitudes required to regain Britain’s declining prosperity’. (Callaghan, J.1976)

Thus, by the time Margaret Thatcher’s new right government had been elected, images of teachers and governors, as self-serving and monopolistic were already becoming subjected to reformation in common sense to justify greater state control and to further regulate the governance and education management.

2.3.5 Education Policy under the Conservatives (1979-1997)-Thatcher’s Legacy on Education

Conservative party conference speeches from 1975-1978 throw light on Margaret Thatcher as one Prime Minister who outlined an alternative course for the nation and for education policy: echoing the individual spirit as opposed to the social (welfare) state. The written transcript of her speeches reveals her as a dominant theme to be the necessity in leading the United Kingdom out of socialism and establishing a free market economy. She emerged victorious after an intense ideological struggle within her own party in which she gained the reputation as the only 'man enough' to stand against Edward Heath (Tricia, M.1978). From the time of her election in February 1975 until the defeat of her government in April, 1979, she led a shift in the ideological focus of the conservative party from the left to the right: instead of a party in sympathy with social democracy and the welfare state under Margaret Thatcher became proponents of free enterprise and de-nationalisation. (ibid: 1978:112). Her worldview was a British economy characterised by free capitalism which served the strong and able bodied and was bent on the shakeup of the welfare state.

'As regards the nationalized industries, the major problem is the defeatist conviction among the public and even among the Conservative politicians that they cannot be unscrambled. Well they can, and details are given in Goodbye to Nationalization (edited by Dr. Rhodes Boyson, Churchill Press.1971)).

Earlier as Minister for Education, Margaret Thatcher had abolished the Free School Meals and Milk initiative implemented by the 1944 Act.

Again, during the 1960s, degree granting polytechnics and colleges which were established by virtue of the 1944 Act and were under LEA (local) control ; and which were seen to be training skills for industry by providing industry with non-advanced and Advanced Vocational qualifications in Agriculture, Business, Art, Accounting and Science were removed. These qualifications were thought to be very necessary at the time. However, they were removed and the technical body charged with providing them was placed under the control of the Department of Education and Science (central control) when Margaret Thatcher assumed office.

As if these were not enough signals from central government, the low tuition fees in colleges and universities which have always remained low were raised.

It is important to drive home the point that since 1945, each student's LEA has paid these fees and awarded also a maintenance grant based upon the parent's ability to provide support; and in certain cases, 'there were no fees charged for admission to colleges, (Act 1944: :section 69) however, the proposals in the Education Reform Era suggested that colleges increase their fess, and not to be absorbed by their LEAs.

In order to demonstrate further how this period was different from the 1944 Era, it is instructive to highlight the role that Margaret Thatcher played in reshaping FE governance. Margaret Thatcher was responsible for signing off and not implementing or (implementing some) proposals in the Russell Committee Report on adult education. The Russell Committee was set up by Labour in 1969 to review non-vocational adult education in England and Wales and to recommend ways of obtaining 'the most effective and economical deployment of available resources to enable adult education to make its proper contribution to the national system. The Commission had three main terms of reference:

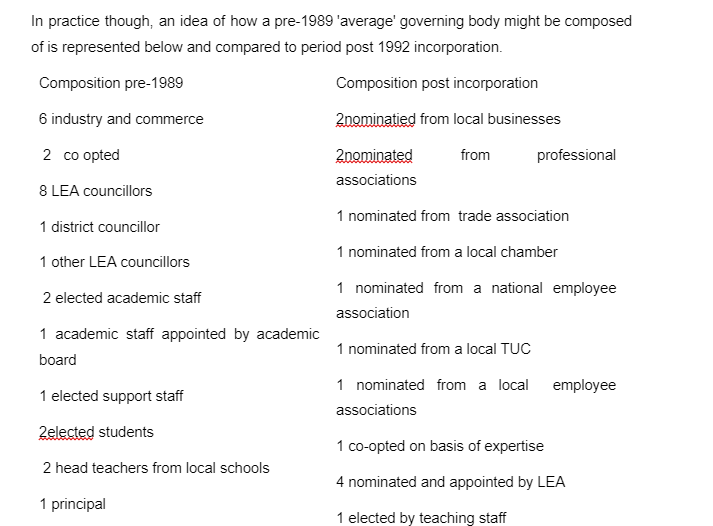

First, it was mandated to assess the need for and to review the provision of non-vocational adult education in England and Wales;