Domestic Violence and Abuse among Black Minority Ethnic Women

Abstract

Background: Domestic Violence and Abuse (DVA) is a global phenomenon, which requires all health and social care practitioners to work collaboratively to support and recognise victims of DVA. This paper presents a review of published studies on DVA amongst Black Minority Ethnic (BME) women. There is paucity of research, which addresses the issue of DVA amongst BME women. According to UK research, an individual’s ethnicity has not been identified as a DVA risk factor. However, there are specific elements, which make BME women vulnerable, and these elements must be taken into consideration by policy makers. Much of the available research on DVA and its interventions focuses on Caucasian women’s experience around DVA. BME population in UK is rapidly growing; therefore, there is a need to explore DVA trends within the BME groups. This study was aimed at exploring the factors, which influence non-disclosure and help seeking behaviour amongst BME women who experienced or are experiencing DVA. The review provides an analysis of the available literature that address DVA amongst BME women.

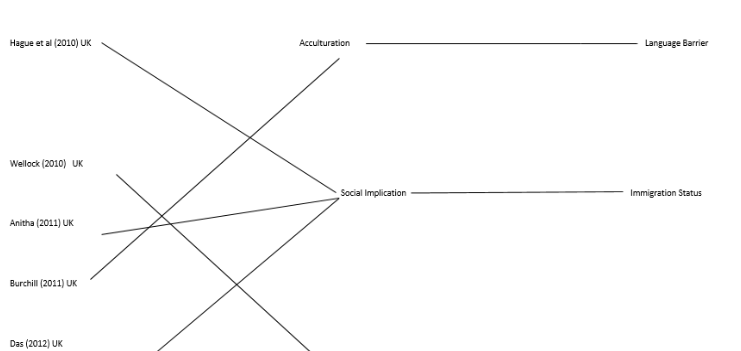

Results: 54 studies were identified and 6 studies conducted in UK met the inclusion criteria. Three key themes emerged from this review, which was Acculturation, Social Impact and BME women perception of DVA. The review also identified that socioeconomic and cultural values amongst BME communities plays a major role in BME women’s ability to disclose DVA.

Conclusion: Understanding BME women’s perspective around DVA aids in developing relevant policies and identifying service provision needed to safeguard victims of DVA and their children. Therefore, there is a need for further research around this topic in order for health visitors and other practitioners gain more awareness around challenges faced with BME women experiencing DVA. In addition, the review identified that the key to supporting and promoting an environment conducive for DVA disclosure, Health Visitors and other practitioners should access appropriate training which equips them with the ability to identify DVA victims and be able to support them in a cultural sensitive manner.

CHAPTER 1: BACKGROUND TO THE REVIEW

Introduction

This chapter provided an overview to the study, which was aimed at examining the context of domestic violence and abuse (DVA) within the Black Minority Ethnic (BME) group. From the integrated literature review, this research identified three main themes including acculturation, social impact and BME women perception of DVS. Citing the work of Burchil (2011), this research highlighted the challenge that health visitors experience while working with refugees and asylum seekers in the UK. This study also presented child safeguarding and risk. Burchil (2011) found that the victims of DVA had difficult cultural adjustments in the United Kingdom, especially those who experienced DVS in their home countries. In particular, women experienced more difficult cultural adjustments once in the UK. This study observed that women continued to live with their abusive husbands even after the right information was offered by the HVs to acquire support services.

On the theme of social impact, this study cited the work of Hague et al. (2010), a cross-sectional study that conducted in India and the UK to investigate immigrant South Asian women experiencing DV. This study notes how Asian women experiencing DV in the UK are often silenced. It also highlighted these women often find it difficult to seek help and support because of their status as immigrants and because of the lack of information concerning their rights. They are also often overwhelmed with their fear and vulnerability thus failing to report any abuse they are going through Furthermore, Hague et al. (2010) note that these women usually find difficulty securing a job in the UK making it difficult to sustain themselves and financially reliant on their abusers.

On the third theme of BME women perception of DVA, this research looked into the work of Wellock (2010) that explored the perception of domestic abuse by BME women’s culture. These women perceived arranging marriage as being a parental responsibility to find a good husband to their daughter. This forced women into some particularly abusive relationships. Additionally, shame due to marriage breakdown was identified to be a factor encouraging women to remain in abusive relationships.

This study also assessed the Health Visitor’s (HVs) role in identifying, responding to DVA and the challenges HVs face in supporting BME women experiencing DVA was also discussed. The definitions of main terms used throughout the study where given in this chapter. In addition, this chapter concluded by outlining the review aim and objectives which were based on the analysis of the evidence.

What is Domestic Violence and Abuse?

Within health, visiting practice DVA is an overarching term, which refers to a type of violence, or abuse, which occurs between family members or intimate partners (Robotham and Frost, 2005). DVA is mainly used by perpetrators to gain control over their victim (Kenney, 2011). Home Office (2019 p.192) define DVA as “any incident or pattern of incidents of controlling, coercive or threatening behaviour, violence or abuse between those aged 16 or over who are or have been intimate partners or family members regardless of gender or sexuality”. There are different forms of DVA that include-

Other forms of DVA include female genital mutilation, forced marriage and child to parent violence (Home Office 2019). Noticeable effects of DVA might be bruises or broken limbs. However, Kenney (2011) warns that, DVA can be complex to identify; not all DVA has visible signs. Therefore, Public Health workers have a crucial role in recognising and responding to victims of DVA.

In some publications, DVA is addressed as intimate partner violence (World Health Organisation (WHO), 2013). Nevertheless, for the purpose of this study the term DVA was used as it is a broad term which also include the violence perpetrated by other family members and not only limited to intimate partners (Menton, 2015; World Health Organisation (WHO), 2013).

Domestic Violence and Abuse trends

DVA affects 1 in 3 women in the UK and in 2018 1.3 million women experienced domestic violence in England and Wales. (ONS, 2019). DVA does not always stop at injury, there have been reported cases of death of DVA victims; for instance, in 2016 two women were killed each week in England and Wales by their former or current partner (Refuge, 2019). In addition, WHO (2013) reported that globally, perpetrators of one-third of female murderers are their intimate partners. Which is a matter of concern, that despite the controversies surrounding DVA and the evidence on the extent of DVA incidence, the government continues to cut down on services that provide early intervention support to these vulnerable women (Siddique, 2018; Ogunsiji, 2016; Sandhu and Stephenson, 2015). Related to this is the problem of non-disclosure of DVA where many victims do not come forward to report the matter (ONS, 2019). The lack of disclosure is problematic due to two reasons; first, the actual incident of DVA remains a ‘grey area’ (Izzidien, 2008). Secondly, the legal and social measures that are in place to help victims are not implemented to protect the victims, as they will not have come forward to report these crimes. Therefore, it is important to explore the DVA disclosure amongst women. In the case of BME women, reasons for non-disclosure are also related to factors, which make it important to explore the issue further from a BME context (Izzidien, 2008).

Most abusive relationships tend to follow a cyclical pattern and the changes between stages are subtle and vary depending on the nature of the abuse (Dugan and Hock, 2013). The cyclical pattern disguises the abusive relationship until the abuse becomes extreme (Dugan and Hock 2013). Conditions of family life and equation between perpetrator and victim may hinder the victim’s help seeking from appropriate sources (Taylor et al., 2013). As DVA is coercive in nature, it is probable that victims may not be able to get help or may be prevented from getting help by the perpetrator (Walby and Towers, 2018).

Walby and Towers (2018) identify DVA as severe form of coercion, which is influenced by gender inequality. Coercive control is “an act or pattern of acts of assault, threats, humiliation and intimidation or other abuse used to harm, punish or frighten the victim” (Women’s Aid, 2019). Coercive control is considered more detrimental to women’s well-being due to the fact that most abusers utilise it to instil fear and compliance in their partners (Stark, 2010; Women’s Aid, 2019). DVA perpetrators usually intimidate and destroy their victim’s sense of value utilising a set of behaviourism to form a framework of power and control over their victims (Woodhouse and Dempsey, 2016). The methods used by perpetrators to lure their victims mainly involve power and control, as identified by the Duluth model (Duluth, 2017). The Duluth model is identified as an effective DVA intervention and on the other hand, it has attracted criticism because the model was developed with the scope of reducing DVA to women perpetrated by male partners and not vice versa (Bohall, Bautista and Musson, 2016). Furthermore, the model’s criticism is that it can be ineffective to some minority communities as it was developed without keeping in mind the minorities, their specific social and cultural conditions (Bohall, Bautista and Musson, 2016).

Why is it important to explore DVA disclosure amongst BME women

Family has been perceived as a safe haven historically, a place where there is protection from the hostile world. However, this has not been the case for more than two million victims of DVA in the UK, who have faced violence within the confines of their family homes (Office of National Statistics (ONS), 2018). The documented estimated numbers of women experiencing DVA was reported to be lower due to the fact that the majority of BME women are reluctant to disclose DVA or seek help (Femi-Ajao, 2010; Das, 2012). Therefore, this study was pivotal in identifying the hindrances in help seeking amongst BME women, to develop disclosure or reveal the real situation in terms of domestic violence and abuse among women in BME and contribute in the development of public health interventions targeted to support BME women.

DVA also has economic costs; in 2017 an estimated £66 billion was utilised in England and Wales to cover direct and indirect costs of DVA whereas £34 014 was the cost per individual DVA victim (Home Office, 2019). DVA can also simultaneously result in loss of productivity; women who are currently in or have recently left abusive relationships are less likely to maintain stable employment (Home Office, 2019). Therefore, DVA is also a financial burden to society with serious social costs. The statistics on DVA that indicate the high incidence level of reported DVA (Woodhouse and Dempsey, 2016) combined with literature that suggests the social and economic cost of DVA, make this issue a major social issue of our times and one that requires social and legal responses.

Women are identified to be at high risk of DVA compared to men mainly due to cultural gender norms such as patriarchal structures and economic dependency (Refuge, 2019; ONS, 2019; Walby and Towers, 2017; WHO, 2017). DVA can affect anyone despite his or her gender, race, age or ethnicity (Manton, 2015). An estimated 695000 men were identified to have experienced DVA perpetrated by women in 2018 (ONS, 2019).

DVA has also been identified to have detrimental effects on other family members. Furthermore, children who witness the violence when it occurs in the home may suffer emotional distress, sleep disturbances, exhibit bullying behaviour towards other children and demonstrate poor school performance (Das, 2012; Manton, 2015). CAADA (2014) states that in addition to the emotional harm caused by witnessing DVA, 62% of children living in household with DVA were also physically hurt by the perpetrator. The psychological effect of DVA on the mother has a negative influence to the mother’s ability to buffer her child/children from the abuse therefore DVA also affect parenting (Moylan et al, 2010; Litherland, 2012). Although the bond or communication between mother and child is one of the protective, factors in children’s response to traumatic stress (Moylan et al, 2010). Research indicates that mothers who are exposed to DVA may show a co-occurrence phenomenon of abuse as an abusive parent (Coohey, 2004).

DVA has been acknowledged as a public and safeguarding issue due to its significant adverse health consequences to the victim and to other family members who witness the abuse (Peckover, 2014). The adverse health outcomes of DVA include physical injury, sexually transmitted diseases, premature birth, low birth weight, suicide, depression, death from homicide, unplanned/unwanted pregnancy and abortion (Ogunsiji, Foster and Wilkes, 2016; WHO, 2013).

Despite the numerous detrimental effects of DVA against BME women on women, children, families and general society, its disclosure has been limited and the real situation or number of women experiencing domestic violence and abuse has not been fully revealed because of the many barriers like fear, cultural influence and perception of the women as a normal cultural thing, the lack of employment, and the lack of information to access support. This report aims to develop disclosure and reveal the extent of DVA among BME women in the UK.

Why DVA amongst BME women should be addressed?

BME is a terminology used in the United Kingdom to describe people from a non-white descent, for example, Black Africans, Asian and Afro-Caribbean’s (Institute of Race Relations (IRR), 2019). Although BME is not a homogeneous group with the same identity, culture, belief and values, they do share everyday experiences of discrimination in the UK (Sandhu and Stephenson, 2015). BME communities are identified to have higher levels of abuse driven suicide and honour based killings (Siddiqui, 2018).

In the UK, there are few studies that explore DVA amongst the BME population even though it is acknowledged that DVA among BME women is not always reported (ONS, 2019). The study by Hague et al (2010) and Femi-Ajao, Kendal and Lovell (2018) concluded that there is need for further research in order to provide insight on the experiences of BME women around DVA. Similarly, Siddiqui and Patel, (2010) and Rehman et al, (2013) demonstrated how national discriminatory policies and practices within statutory agencies often exclude the experiences of BME women. Therefore, there is a need to explore the experience of the BME women with respect to DVA.

In 2011, an estimated 13% of the UK population was from the BME group and this figure was predicted to rise to 30% by 2050 (ONS, 2015). Therefore, due to this rapid growth of the BME population in the UK, a gold standard systematic review was deemed essential. This would ensure that DVA amongst the BME population would be identified, responded to and enable provision of support services tailored for the needs of BME women.

Nevertheless non-disclosure is not only limited to BME community, it is a theme amongst the majority of DVA victims (Bradbury-Jones, 2015). Taylor et al (2013) suggest that victims of DVA conceal their abuse to professionals due to fear and confidentiality reasons. Furthermore, Femi-Ajao (2018) and Siddique (2018) suggests that BME women are often subject to intersectional discrimination that may also hinder their ability to seek help. Intersectional experiences are commonly reported with respect to victims of DVA, where the intersection between gender, race and class can play important roles in how women experience and respond to DVA (Marchetti and Daly, 2017). Intersectional approach has come to be increasingly adopted by feminists who seek to consider DVA as a phenomenon, which does not rigidly fall into category of a radical approach (George and Stith, 2014).

HV’s and midwives have been identified to make stereotypical assumptions on which women are likely to disclose their DVA experience depending on culture or background, despite the national guidelines to support practitioners’ decision-making in DVA interventions (Taylor et al., 2013). Most practitioners including HVs appear to struggle with the complexities that dominate BME women’s lives around DVA experience (Siddiqui, 2018). Several studies have highlighted the importance of practitioners’ understanding of BME women’s perceptions around DVA and disclosure as essential to identifying interventions and treatment options designed to combat DVA (Stockman, Hayashi and Campbell, 2015: Vanda, 2010). However, the national guidelines available to question DVA may not be appropriate for BME women, and health care professionals have been found to lack cultural awareness that is vital in supporting BME women (Vanda, 2010). In addition, NICE (2014) encourages professionals to tailor their support to meet the needs of the DVA victim.

Similarly, Ruggieri et al (2013) study suggest that health professionals failed to identify DVA due to lack of expertise in assessing and psychologically understand DVA victims even though 80% of women visiting Emergency Rooms were victims of DVA.

Health Visitor’s role in recognising and responding to DVA

HVs are registered nurses/midwives with a Specialist Community Public Health Nursing (SCPHN) qualification (Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC), 2004). HVs central role is to ensure that every child and young person have the best start in life through assessing and providing appropriate interventions as per assessment outcome. HVs work in partnership with the parents/carers, statutory and non-statutory agencies to provide support to families with children under 5 years old (Institute of Health Visitor (IHV), 2019). Safeguarding and Child Protection are core activities of health visiting and HVs are well placed to undertake this role (Eynon et al, 2012; Bradbury-Jones 2015; Luker, McHugh and Bryar, 2017). HVs are amongst the frontline staff that has opportunity to identify DVA manifestation when visiting families for routine service provision (NICE, 2016). Therefore, HVs are expected to offer appropriate support to the victim and family when DVA is disclosed or identified.

In 2005 National Health Service (NHS) introduced routine asking of DVA by Health professionals to women for them to disclose if they are victims of DVA (NICE, 2014). This practice was aimed at enabling healthcare professionals to challenge DVA, empower the victim and simultaneously reduce health inequalities (Bradbury-Jones, 2015). However, this phenomenon is contested due to HVs lack of knowledge and understanding of the link between DVA and the influence of race/culture in uncovering DVA in BME communities (Bradbury-Jones, 2015). In concurrence, Donetto el al, (2013) also criticised health professionals including HVs for failing to identify the nature of DVA among BME women in their study with BME groups experiencing high levels of DVA. Furthermore, nearly three quarters of children on the At Risk register live in households where there is domestic violence, which most of the victims are reluctant to engage with the statutory plans, and this continues to be challenging to support these families to safeguard their children (Birmingham City Council, 2009). Hence the rationale for undertaking this review.

What is the current state of knowledge?

Several studies have suggested that BME women are disproportionately affected by DVA compared to their white counterparts (Stockman, Hayashi and Campbell, 2015; Izzidien, 2008). This disproportion significantly amplifies the fact that BME women are more likely to face barriers such as isolation, language and lack of knowledge in accessing DVA support services (Stockman, Hayashi and Campbell, 2015: Walby and Towers, 2018).

The ONS (2019) identify DVA as a complex public health concern, which is challenging to ascertain its actual statistics. The figures of DVA occurrence are grossly underestimated and it is considered that BME women only seek support when the violence is more severe (Women’s Aid, 2015; Ogunsiji, 2016; Sisters for Change, 2017). In 2017, it was reported that the total number of victims of DVA recorded from the BME women was 9.6% compared to their white counterparts, which were 87.8% (ONS, 2019). Refuge (2019) states that even if a woman experience one hundred DV incidents, only five will make it to official data. Despite these alarming statistics and the growing number of BME community in the UK, very little is known about the extent and nature of DVA amongst the BME community (Femi-Ajao, 2018). It has been documented in literatures the significant role of alcohol and other drugs play in DVA (Gadd et al, 2019). However, knowledge of contextual risk factors to DVA such as cultural beliefs and social norms is still limited, so as our understanding of what constitutes appropriate prevention and intervention strategies amongst BME women (Bradbury-Jones, Clark and Taylor, 2017).

What are the gaps in the current knowledge?

DVA is sometimes a lifelong issue for some BME women as they are reluctant to seek help as they may have a higher social acceptance of DVA within their culture because men often regarded as breadwinners, head of the family and women are considered to be subordinates (Ogunsiji, 2016). BME women may not report the DVA to professionals due to their cultural values, which encourage women to keep domestic issues within the private domain or fear of racist response from professionals (Women’s Aid, 2015; Ogunsiji, 2016; Femi-Ajao 2018). Furthermore, it has been identified that some BME women do not understand what constitutes DVA, and this has been a contributing factor for not seeking help as they normalise the abuse (Das, 2012; Hague et al, 2010; Women’s Aid, 2015). Therefore, there is definitely a need to fill this gap in knowledge in order for the BME women to make autonomous decisions regarding their safety and of their children. In concurrence, The Ending Violence against Women and Girls Strategy (2016-2020) identify raising awareness of DVA through educating women and girls as a preventative measure to combat DVA (HM Government, 2016).

Most BME women who are affected by DVA are dependent on their partners for income and experience social exclusion such as inadequate housing, poverty, lack of access to education and unemployment (Vanda and Wellock, 2010). Walby and Towers (2018) also concur that the economy has a significant impact on DVA, and this was evident in the 2008 UK economic crisis, the numbers of domestic violence crime escalated. The ONS (2019) further notes that women whose immigration status is dependent on their marriage are most likely to experience DVA. It has been recognized that BME women’s immigration status amongst other social implications, which might be, linked to financial stability play a major role in their help seeking ability (Das, 2010; Anitha, 2011, Femi-Ajao, 2018).

Furthermore, before 2002 women on spousal visa were threatened with deportation if they leave their relationship during their 2-year probationary leave (Anitha, 2011). This policy was reviewed and replaced with Domestic Violence Concession Rule 289A (2002), as the exposed women and their children to significant harm (Anitha, 2011). Under the Domestic Violence Concession Rule (2002) victims of DVA who entered the UK on a spousal visa where able to apply for Indefinite Leave to Remain (ILR) if they can prove that, DVA is the reason for their relationship breakdown (Anitha, 2011). Furthermore, it was acknowledged that during the period of ILR application these women are vulnerable and prone to be destitute due No Recourse to Public Funds (NRPF). Therefore, Destitution Domestic Violence (DDV) concession allowed victims of DVA to apply for access to public funds (Home Office, 2019). Current research claims that even though these policies are in place, not every BME woman is ware of them or aware of how to access the support (Haque et al, 2010; Wellock, 2010, Burchill, 2011).

Furthermore, in response to related gaps in knowledge and responses to DVA, NICE (2016) introduced quality standard with key recommendations and guidance for frontline staff to improve their care provision to DVA victims and the perpetrator by identifying areas of their own improvement and offering appropriate support.

Aim and objectives

In order to conduct a well-focussed literature review it was essential to start with a clear research question (Aveyard 2019). The PICo (Population Interest Context) framework was utilised to guide the question formulation as it enabled a more exploratory analysis of the phenomenon compared to PICO (Population Intervention Comparison Outcome) which is mainly used for quantitative questions (Wakefield, 2014).

The aim of this integrated review was to summarise existing research on BME women’s experience around DVA and disclosure.

The objectives of the review were to:

To examine factors which influence the majority of BME women experiencing DVA not to seek help

To understand the impact of DVA on BME women and their children.

To explore how HVs can encourage help seeking amongst BME women.

Conclusion

DVA is a violation of the victims’ human rights and for women victims it may depict gender inequality. DVA undermines the health, dignity and autonomy of the victim, yet it remains masked in a culture of silence. HVs are amongst the key health professionals who normally have the opportunity to identify and provide DVA aimed interventions. Although there is little evidence, which suggests that BME women experience more DVA that other ethnic groups, it can be suggested, BME women experiences around DVA may be different due to cultural factors, problems of accessing help services due to language barrier and discrimination. Most DVA against BME women is deeply rooted in traditions that value men more than women. These factors are likely to make BME women’s experiences of DVA difficult to respond to. Therefore, given the complexities around DVA disclosure amongst BME women, exploring and understanding their perceptions around their experience is intrinsic for development of support services for BME communities. Furthermore, professionals who work with victims of DVA need to acknowledge that culture is not bound by borders; individuals rich or poor, educated or non-educated take their culture with them wherever they go (Robotham and Frost, 2005; WHO, 2013; Home Office 2019).

Chapter summary

The definition of DVA was presented in this chapter alongside an overview of DVA amongst BME groups. Gaining an understanding on how culture and other social factors impacts DVA disclosure within BME communities will offer valuable information to health visiting practice. Furthermore having an insight on BME women’s experience will be pivotal to other practitioners and policy makers working in the field of DVA in the United Kingdom. The next chapter discussed the literature search strategy utilised in identifying literature addressing the key issues relating to DVA within the BME community. The studies were critically analysed and common themes were drawn from the studies included.

Chapter 2: THE INTEGRATED LITERATURE REVIEW

Introduction

This chapter examined the existing literature exploring domestic violence and BME women. The factors that hinder DVA disclosure among BME women were discussed in Chapter 1. In order to provide a comprehensive understanding of the study topic, a systematic approach was utilised to identify available literature and a clear methodology was described (Aveyard, 2019). This chapter concluded with the description of emerging themes from identified studies.

The Literature Review

An integrated literature review is a comprehensive methodological approach of reviews that provides synthesis of knowledge by allowing inclusion of experimental and non-experimental studies to fully understand the phenomenon been analysed (Aveyard, 2014; Tavared de Sauza, Dias deSilva and de Carvalho, 2010). Furthermore, integrated literature review enables the reviewer to create new knowledge, identify gaps in research (Torroco, 2016). Therefore integrated reviews are considered as a valued evidence based practice tool (Tavared de Sauza, Dias deSilva and De Carvalho, 2010). Conversely, literature reviews are criticised that they may yield misleading information, as there is no set method to ensure all the literature in the topic has been considered in the review (Moule, 2018). Hence, the literature searching skills need to be robust in order to identify all relevant literature (Bettany-Saltikov and McSherry, 2016).

Search strategy

The literature search strategy was well defined in order to enhance rigour of the review by minimising the potential of yielding inaccurate results by ensuring complete and unbiased result (Whittemore and Knafl, 2005; Aveyard, 2014). An extensive systematic search permitted the provision of up to date evidence and minimised publication bias (Parahoo, 2014). Bettany-Saltikov and McSherry (2016) warns that negative results are not always published as much as positive results in journals therefore a wide literature search strategy is pivotal in yielding unbiased results. Addressing publication bias was pertinent in this review due to the nature of the review that aimed to understand human behaviour (Whittemore and Knafl, 2005).

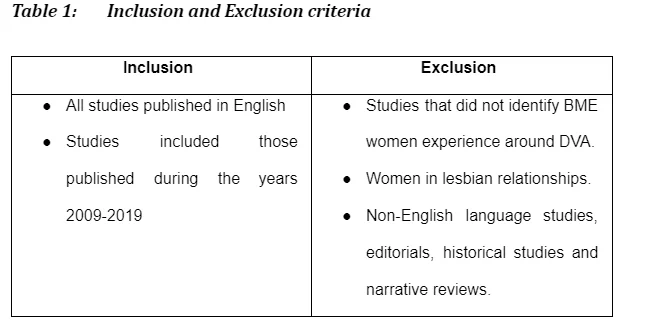

A rigorous and transparent reported inclusion and exclusion criteria was essential as it limited the number of literature to be reviewed and guided the study selection process (Togerson, 2003 in Bettany-Saltikov and McSherry, 2016). See table 1 for inclusion and exclusion criteria.

The databases searched to identify primary research articles included: CINAHL, University Library Search, Medline, SocIndex, Nursing, and Allied Health Service. These databases were deemed appropriate for literature search, as they are relevant for nursing research (Halcomb and Fernandez, 2015). Computerized databases are criticised due to limitations linked to search terms and indexing problems that may yield 50% of the eligible studies (Whittemore and Knafl, 2005). Therefore, appropriate search terms were used in order to identify relevant literature (Parahoo, 2014). The Boolean operator OR was used to expand the search (Wakefield, 2014).

There was a plethora of information; hence, a more focused search was undertaken using the keywords and Boolean operators, AND to narrow the search (Wakefield, 2014). There was a dearth of information relating to DVA and BME women. Therefore, a comprehensive search of literature was performed, which included hand searching of journals relevant to the study topic cited by researchers in their references (Aveyard, 2019; Halcomb and Fernandez, 2015). English papers worldwide including studies conducted in America were also analysed to ascertain if there were similar themes as identified in the UK. Furthermore, the search did not limit to full text only, as there were other ways of getting the full text of the studies identified. In addition, researchers who conducted research on the similar topic were contacted to ascertain if they had any unpublished studies elsewhere. This comprehensive literature search strategy minimised the risk of cherry picking literature (Aveyard, 2019).

Search outcome and Study selection

The initial search from the databases using keywords: - domestic violence, yielded 9264 articles. 8841 articles were excluded after application of BME or Black minority ethnic group keywords. The second search yielded 423 studies published between 2010 and 2019. 372 articles were excluded, as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Further three articles emerged through hand searching the reference lists of the included studies.

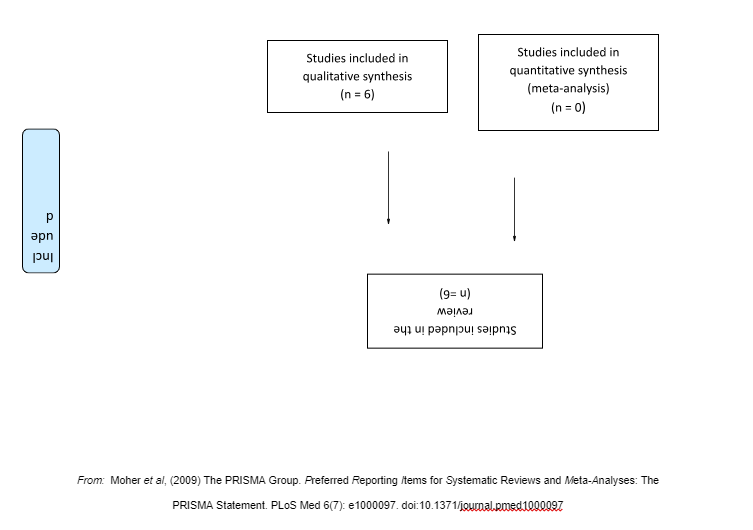

The journal titles and abstracts of the 54 identified studies were reviewed. 48 articles excluded, as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Aveyard (2019) recommend that following in depth critical appraisal any papers that seemed relevant at initial review of the abstracts but no longer relevant to the study should be discarded at this point. 3 of the articles excluded were duplicates. Majority of studies did not focus on BME women’s experience around DVA, hence they were excluded. A total of 6 articles were selected, as they were deemed appropriate for the review, based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. See figure 1 the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis) flowchart for the literature selection process (Liberati et al, 2009). The PRISMA model is a widely accepted gold standard for reporting studies and it enables an audit trail for the reader (Aveyard, 2019).

See appendix 2 for the summary of the included studies. All the studies included were qualitative. Qualitative approach provides exploratory analysis of human behaviour and it is an important evidence base for nursing research (Lipp and Fothergill, 2015). The quality of each study included in the review was assessed by the author against the criteria outlined by the validated CASP tool for qualitative studies (CASP, 2018). The CASP tool comprises of ten questions, which was used to appraise the studies, see appendix 1. The study quality was not an inclusion criterion for studies in this review. The CASP tool was utilised as part of the qualitative systematic review process (Bettany-Saltikov and McSherry, 2016).

Assessing the methodological quality of included studies enables the reader to evaluate the potential bias in each study (Halcomb and Fernandez, 2015). Similarly, Windle, Bennett and Noyes, (2011) mention that reviewing study quality is a vital component in evidence-based practice as confirms the credibility and reliability of evidence. However, Whittemore and Knafl (2005) claim that there is no gold standard for evaluating methodological quality in an integrated review.

Data extraction and Synthesis

The data extraction process identified by Whittemore and Knafl (2005) was adapted in this review in an attempt to answer the review question (Bettany-Saltikov and McSherry, 2016). The included articles were read by the author, in order to extract data, summarising the main points (Parandeh et al, 2016). Conversely, having one author analysing and synthesising data could diminish validity of the study (Parandeh et al, 2016). Therefore, as a novice and single-handed researcher, the author meticulously analysed the studies a couple of times in order to enhance rigour and ensure that no important pieces of information were missed during synthesis (Wakefield, 2014). A data extraction form was used to standardise the data extraction process and to improve validity of the results (Bettany-Saltikov and McSherry, 2016). To ensure data extraction rigour and to avoid premature analytic closure, the discernment of patterns and themes were verified with the primary sources for accuracy (Whittemore and Knafl, 2005).

Themes from the literature review

A thematic analysis approach to data synthesis by Whittemore and Knafl, (2005) was adopted to identify key elements from the data and integrate results from the included studies. Thematic analysis also enabled the author to identify any similarities, differences and gaps in research (Polit and Beck, 2017). The themes, which were identified from each study, were summarised and combined with themes from other papers in order to identify common themes (Aveyard and Bradbury-Jones, 2019). To facilitate understanding of the key concepts of the included studies the studies were read multiple times. The themes were aligned with the study objectives in order to facilitate maximum use of available data (Femi-Ajao, Kendal and Lovell, 2018). Appendix 3 demonstrates the initial identification of themes from the data. The three themes were-

Acculturation

Social Impact

Theme 1 – Acculturation

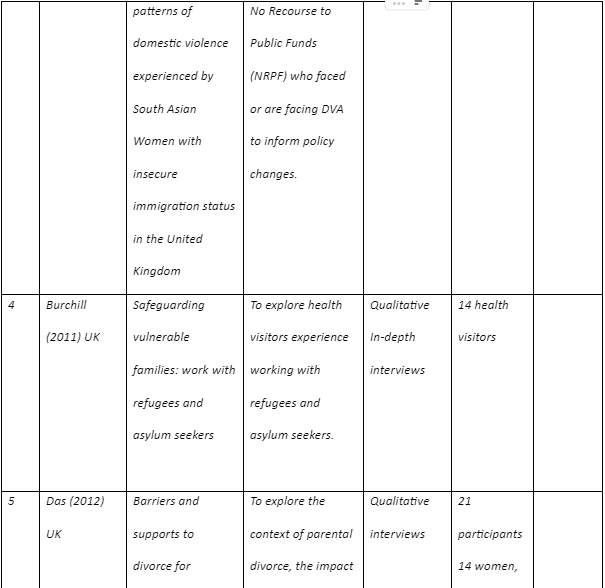

Burchill (2011) examined safeguarding vulnerable families and the challenge health visitors experience working with refugees and asylum seekers in the UK. The study was undertaken in 2006 framed by Laming’s (2003) recommendations following the Climbie Inquiry. Burchill (2011) presents one of the key findings that focused on child safeguarding and risk. Fourteen health visitors were purposely sampled based upon experience: work with vulnerable and marginalised communities in an area with concentrations of refugees and asylum seekers (Burchill, 2011). Ethical approval was explicit. The main premise of his argument was that working with the most vulnerable groups gives rise to complexity of need (Burchill, 2011). The data collection method was in depth interviews conducted at health centres across London, United Kingdom.

Participants in the study mentioned that they identified amongst the victims of DVA they were working with that cultural adjustment in the UK was a challenge, especially where DVA had been witnessed in their country of origin (Burchill, 2011). The participants interviewed mentioned that women they supported found it difficult to make cultural adjustments once in the UK. The other cultural adjustment challenge identified by the participants was most women who were supported perceived the perpetrator/husband as the head of the family therefore; they believed he has the right to heat his wife. Furthermore, HVs also mentioned in that even though they had provided the women they were supporting with information on support services they would still chose to live with their abusive partners.

Theme 1: Conclusion

Learning a new culture can be challenging for some BME women because their perpetrators or families would have instilled barriers for the women to remain in abusive relationships. Acculturation has been linked to non-disclosure of DVA due to its contribution to stress integrating to a new culture and economic pressures. Women found it difficult to acknowledge that DVA is a breach of Human Rights due to the way DVA is perceived in their culture or country of origin. Therefore, migrating to the UK is a major change in regards to BME women’s lifestyle and culture. It is acknowledged that changes following migration increase vulnerability encountered in a new country that may lead to acculturation stress that may in turn result to increased risk of DVA (Burchill, 2011).

Theme 2 – Social impact

Hague et al (2010) is a cross-national study that reported on a small action based study conducted by researchers from India and UK working collaboratively to investigate the accounts of newly immigrant South Asian women experiencing DV. The study was carried out in two stages. First stage involved interviewing South Asian women who immigrated to UK and then experienced marriage difficulties and the second stage involved feeding back to organisations in India (Haque et al, 2010). The study was undertaken between 2007/08 supported by a small grant from British Academy on the initiative of Nirmala Niketan partners following their pilot interview on a group of women living in a specialist South Asian Domestic Violence Refuge in UK (Hague et al, 2010). The main premise of the study was to accentuate the views of immigrant South Asian women experiencing DVA who were marginalised and silenced in the UK (Hague et al, 2010). Ethical approval of the research was not clearly documented in the study. The study sample comprised of sixty seven mostly newly immigrant South Asian women with experience of DVA. The data collection methods for the study were interviews and focus groups which were held at various locations UK and some of the venues were withheld, as they did not wish to be identified (Hague et al, 2010).

Many of the research participants reported the factors that hindered their ability to seek help were their immigration status and lack of information regarding their rights exacerbated their fear and vulnerability (Hague et al, 2010). One of the participants interviewed in the study mentioned she was exposed to DVA for 15 years without knowing she was eligible to apply for British citizenship (Hague et al, 2010). The participant further mentioned that she was made to believe that if she leave her husband or report the DVA to the police she would have no right to remain in the UK (Hague et al, 2010). Furthermore, inability to secure employment for some of the BME women interviewed hindered their ability to leave abusive relationships, as they were financially reliant on the perpetrator. Participants expressed that not knowing their rights, influenced their ability to seek help, as they felt threatened that if they disclose DVA they will lose their children (Hague et al, 2010). Spangaro et al (2011) study had similar findings that suggest that women conceal DVA due to fear of having their children taken away.

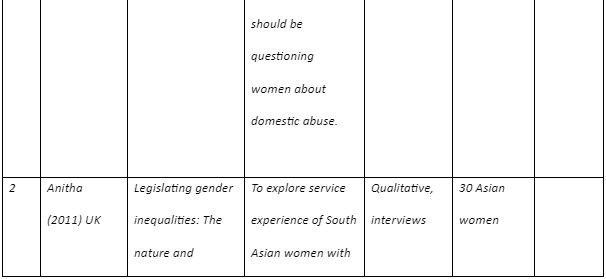

Anitha (2011) explored the experiences of Asian women living in North West and Yorkshire regions of England with NRTPF who experienced DVA accessing DVA services. The study was conducted in 2007 and it was aimed at inform policy changes in the UK. Women included in the study were mainly from India, Pakistani, and Bangladesh. The data collection method utilised in the study was semi-structured qualitative interviews conducted in Urdu, Hindi, and Punjabi (Anitha, 2011). Thirty women were purposely recruited for the research. Twenty of the women recruited were accessing domestic violence services and other ten women were living with family or friends, recruited via word of mouth and chain method (Anitha, 2011). Ethics approval was in place prior to the study commencement.

Participants mentioned a number of social implications which hindered help seeking which included DVA being perceived as a norm in their culture (Anitha, 2011) One women in Anitha (2011) study mentioned that she came to UK with the aim of improving her life but did not turn out as expected, the abuse escalated and perpetrator isolated the women. According to research, most perpetrators utilise a mixture of controlling behaviours that might include isolation to instil fear in their victims (Bradbury-Jones, Taylor, Kroll and Duncan, 2014). The biggest fear identified amongst the women interviewed in the study was being returned India (Anitha, 2011). This was evident in the study when one woman mentioned that her visa had expired and the in-laws threatened her that they will “Deport her with her baby” (Anitha, 2011).

Femi-Ajao (2018) study explored the factors that influenced disclosure and help seeking amongst Nigerian women resident in the UK who had experienced DVA or are experiencing DVA. The research was conducted as part of the PhD research and the study aim was prompted following the researcher’s experience in 2008 when she came in contact with a victim of DVA who was reluctant to discuss her DVA experience (Femi-Ajao, 2018). The DVA victim later married the perpetrator despite being advised to flee the relationship and she blamed herself for provoking the perpetrator (Femi-Ajao, 2018). The study participants were recruited from Nigerian Community groups, faith based organisations and the Manchester No Recourse to Public Funds team. The research was conducted between 2012-2013 in the homes of participants in Manchester and University of Manchester and the data collection method was in-depth semi structured interviews (Femi-Ajao, 2018). The Ethical approval was explicit.

Participants identified lack of finances to sustain themselves was amongst the obstacles women face when thinking of leaving their abusive relationships (Femi-Ajao, 2018). Femi-Ajao (2018) also recognises that the participant’s immigration status contributed to their financial dependency on the abuser (Femi-Ajao, 2018). Majority of the study participants were on a spousal visa and they feared deportation and destitution (Femi-Ajao, 2018). One study participant expressed that she was afraid to report DVA because she was told if she reports to the police they would be both deported (Femi-Ajao, 2018). Therefore, it is very important for professionals to be able to identify signs of DVA, ask about DVA routinely, offer advice and give information on local DVA support groups (Burchill, 2011; Bradbury-Jones, Taylor, Kroll and Duncan, 2014).

Theme 2: Conclusion

The data from all the studies included suggests that DVA disclosure was facilitated by a combination of overlapping issues triggered by the sociological impact of DVA encountered by BME women. Participants in all the studies included indicated that that due to some of the negative impacts were reluctant to seek help.

Theme 3 - BME women perception of DVA

Wellock (2010) explored how domestic abuse is perceived within the BME women’s culture and to identify who should be questioning women about domestic abuse. The study was aimed at addressing the gap in knowledge due the rise of maternal deaths among BME women following the report Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths in 2001 (Wellock, 2010). Semi-structured interviews were conducted to collect data. Six non-pregnant BME women from Bangladeshi, Somalia, Pakistani, Somalia and Sudan living and working for the primary care trust in Manchester, UK were purposely selected for the study (Wellock, 2010). Ethical approval was explicit.

Participants did not acknowledge that marrying a husband chosen by her parents might be similar to be coerced into a relationship due to the fact that they perceived arranging marriage is a parental responsibility to find a good husband to their daughter (Wellock, 2010). It is illegal in UK to force or pressurise someone to agree to marry (Home Office, 2012). Shame due to marriage breakdown was identified to be a factor encouraging women to remain in abusive relationships (Wellock, 2010). One participant mentioned that being married made her more acceptable within her culture (Wellock, 2010).

Das (2012) is a UK study that explored the narratives of British-Indian adult children who experienced and witnessed parental DV or parental divorce and their perspectives on the choices and decisions their mothers made in staying or leaving the marriages and the support that affected their decisions. The study was aimed to address the gap in knowledge on what hinders BME women to escape violent relationships (Das, 2012). The study was part of PhD and ethical approval was explicit. The participants of the study were recruited via advertising the study in South Asian localities, temples, student groups, career centres and various internet blogs. Initially Twenty-one participants from the British – Indian ethnicity volunteered, fourteen females and seven male participants and eight participants were excluded, as they did not report DVA and victimisation of their mothers (Das, 2012). Thirteen participants were finally recruited for to participate. The age of parental divorce ranged from six months to twenty two years. Interviews were used to collect data. Sixteen participants were interviewed via telephone and five participants were interviewed face to face.

Das (2012) study mentioned that women were exploited, did all the housework on top of a full time job. Furthermore, paternal family’s interference was identified to be linked the abuse of the women (Das, 2012). Das (2012) mentions that women resisted seeking support in order to protect their privacy. BME perceived DVA should be kept private as it is associated to shame and women are often blamed for DVA due to patriarchal norm. The main findings of the study suggested that BME women normalise DVA due cultural norms and patriarchal institutions that disempower women (Das, 2012).

Theme 3: Conclusion

In conclusion, most studies that explored DVA amongst the BME community suggest that the husband is seen, as the head of the family- patriarchal hierarchy has been evident as a reason of normalising DVA (Das, 2011, Femi-Ajao, 2018 and Hague et al, 2011). How an individual perceive their situation or experience is suggested to be the first step of acknowledging that they need help, without self acknowledgement any support intervention would not be successful (Craven, 2010; NICE, 2014). Interventions like the Freedom Project which focus on empowering the victim have been identified to be successful because the victim is given information for them to make informed decision(NICE, 2014).

Chapter Summary

Cultural backgrounds affects BME women’s beliefs and attitudes towards their decision making around their DVA experience as demonstrated in 83% of the studies included (Wellock, 2010; Anitha, 2011; Burchill, 2012; Das, 2012; Femi-Ajao, 2018). The main factor which hinder disclosure has been discussed above social implications as identified in most studies is linked to economic and cultural values. Immigration status was identified to be a common factor amongst BME women who settle in UK on a spousal visa. In contrast for BME women who have settled status it was mainly cultural values that contributed to their lack of DVA disclosure. In the next chapter was narrated in sub-themes that were created following further analysis of the included studies. While existing evidence suggests BME women are likely experience DVA and not seek help, due to their cultural and social beliefs.

Chapter 3: ANALYSIS AND INTERPRETATION OF THEMES

Introduction

This chapter presents the analysis of the initial themes that were restructured to create sub-themes to incorporate emerging findings based on the author’s critical analysis (Anitha, 2011). The study utilised the thematic analysis recommended by Aveyard (2019) which involves breaking down relevant data into different modules and discussing how it relates with each other. The study topic was the starting point of the thematic analysis. This served as guide and enabled the author to address the study topic and objectives. New research was utilised to support this analysis.

Synthesized thematic findings

The main DVA disclosure related findings amongst BME women identified in the six reviewed papers are highlighted in appendix 3. The sub-themes are illustrated in figure 4.

Sub-theme: 1 – Language barrier

Hague et al. (2000) and Burchil (2011) have highlighted the problem of language barrier under the main theme of acculturation. From the introduction section, it has been highlighted that one of the reasons why the issue of DVA is prevalent among BME women in the UK is because of lack of sufficient research or study in this area, which is partly because of the issue of language barrier. This is a cultural adjustment problem. In a previous study conducted by Tipton (2018), it is indicated that the absence of sufficient reporting of domestic violence and abuse by women from black and ethnic minority groups has greatly hindered efforts to stop. Additionally, this author notes that women from these groups particularly those from South Asia are not likely to access services leave alone report their experiences. According to Tipton (2018), culture and language are of a lot of significance, particularly to the women who seem reluctant to seek help and services. This researcher claims that these women might be lacking a comprehension or an understanding of their needs and experiences. The other challenge noted by Tipton (2018) is that even though more women from ethnic minority groups are seeking for domestic violence and abuse services unlike in the previous days, the mainstream services are yet to have the capability to offer them adequate appropriate services that satisfy their needs.

The problem of sticking to their usual way of life or culture, and persevering in abusive relationships as well as the inability to access support, help or the right information because of a language barrier makes it easy for these women to go through domestic violence and abuse. Language barrier has been identified in various studies as contributing factor why BME women are sometimes reluctant to seek help due to lack of knowledge and awareness of DVA support services (Wellock, 2010, Das, 2012, Femi-Ajao, 2018). Reina, Lohman and Maldonado (2014) study that was conducted in America had similar findings that demonstrated that Latina women faced major barriers in seeking help because there was lack of bilingual service providers. It is agreeable that the problem of communication is a big issue, even for those who might be interested in seeking help but cannot communicate effectively in English. This in addition to their status as immigrants can make these women, or men, going through abuse, reluctant to seek help. Wellock (2010) and Anitha (2011) studies add to the issue of language by stating that interpreting services was available but there was an issue around gossiping and the lack of confidentiality amongst the women and interpreters within the community, also mentioning this as one of the reasons why BME women withheld information regarding their experience (Wellock, 2010). For those women who finally gathered the courage to seek help, professionals in the UK find difficulty in acquiring the right or accurate information from women who experienced DVA using interpreters. Wellock (2010) contend that there have been cases where interpreters misrepresent information. Conversely, it is likely that without accurate presentation of the women’s account of their DVA experiences it becomes challenging to provide appropriate support to the BME women (Femi-Ajao, Kendal and Lovell, 2018). Interpreters who provide misleading information have likely also made it difficult for researchers to find accurate information about DVA among BME women in the UK. Evidently, from these pieces of research, language barrier, which falls under the theme of acculturation, is a huge problem with regard to BME women experiencing domestic violence and abuse.

The culture and language barrier of women from ethnic minority groups also influences the attitude of the professionals offering services to those experiencing domestic violence and abuse. According to Tonsing (2016), assumptions and stereotypes about the language and culture of women from ethnic minority groups often shape the kinds of service response offered to the victims of abuse. This author notes that most often, healthcare professionals, including those offering mental health services to victims of violence or abuse who are suffering from depression, stress or anxiety often find it hard communicating with people who do not understand or cannot communicate using the English language. Therefore, they become reluctant in accepting them as patients. Women from ethnic minority groups are also stereotyped as quite uncivilised or even violent. As a result, they are seen as the causes of problems of violence and abuse in their families. This makes those offering DVA services quite reluctant to serve them or help them (Tonsing, 2016).

Besides the fear of being stereotyped, Rai and Choi (2018) claim that women from ethnic minority groups are usually reluctant to engage the DVA services and seek help because they are concerned about being judged by the professionals and rest of society. As mentioned by other literatures, these authors claim that most cultures hold family honour to a high esteem. Women are afraid of how the professionals offering DVA services will view them and how society will judge them if it comes out that they reported their secrets or inner family issues to outsiders. Because of this, they chose to keep their suffering a secret and from the public by not seeking help.

From a unique perspective, the research of Lee, Sulaiman‐Hill and Thompson (2013) bring new light under this acculturation barrier. One important factor that this research brings to light is the issue of culturally inappropriate service models adopted by the UK government. Policy makers and those in charge of offering domestic violence and abuse services have not factored the issues of culturally sensitivity in their approaches. For instance, women from other cultures, like those from Muslim countries might find it difficult to attend the services when they have to meet a man alone, particularly non-Muslim individuals to express themselves. The services have failed to consider how culturally inappropriate the services they offer can be to those from ethnic minority ethnic groups (Lee, Sulaiman‐Hill and Thompson, 2013). Another factor is failing to ensure that the institutions offering DVA services are culturally diverse, to encourage those who are afraid of visiting the premises because of feeling out of place to attend and seek services. The lack of cultural diversity in these institutions have also continued to worsen the language barrier problem, because most often, the women who wish to seek help cannot communicate well in English and shy off when they know they will not be able to say their problems and be understood. Women from ethnic minority groups might also believe that the services being offered in institutions that are not culturally diverse are limited, and are offered only to the popular group like white people (Lee, Sulaiman‐Hill and Thompson, 2013).

Sub-theme: 2 – Immigration status

Analysis of the main theme, social implication as discussed by Anitha (2011), Hague et al. (2010) and Femi-Ajao (2018) has led to a single sub-theme of the immigration status as a factor that affects BME women, increasing their experiences of domestic violence and abuse because of their status as immigrants. Most BME women emigrate to developed countries for the purpose of seeking a better life However, on their arrival in these countries and after establishing their lives there, not establishing per say, but after surviving for a while, they begin to experience the real challenges that come with the status of being an immigrant. One of the social implications that have emerged out of these literatures is the immigration status. This status and the lack of proper documentation such as health insurance and so forth makes these women reluctant to seek help when they are experiencing domestic violence and abuse.

Adams and Campbell (2012) who state that women from ethnic minority groups living in the UK, especially the immigrants, are afraid of the UK authorities support these claims. They are afraid of government institutions such as the housing department, immigration department, taxation, courts, the police and child protection. Women experiencing domestic abuse and violence are afraid of reporting their cases and situations because their immigrant status means that they risk losing their houses. They also fear that they might be arrested and taken to court that might lead to losing their children to the child protection agency. Additionally Adams and Campbell (2012) note that the families’ small businesses that help them survive might begin to be taxed. As a result, they prefer to keep silent with their domestic violence and abuse due to the fear of losing everything they have built over time. Women in these situations suffer most because in most of these cultures as mentioned by Adams and Campbell (2012), their cultures promote remaining submissive to their husbands.

Immigration issue is usually central to most BME families where DVA is reported (Hague et al, 2010 and NICE, 2016). The majority of participants from all the six studies included mentioned immigration as one of the factors that was pivotal amongst BME women for them to disclose DVA or seek help. Consequently, without a valid UK visa BME women were concerned that they could not access social benefits, find employment or can be deported to their country of origin, therefore they would not be able to provide for their children (Hague et al, 2010; Anitha, 2011, Burchill, 2011). Participant mentioned that she stayed with the perpetrator due to fear of being separated from her children as children as she felt without appropriate visa she would not be able to support the children (Anitha, 2011; Burchill, 2011; Das, 2012). The UK Boarder Agency has outlined policies like to ensure immigration procedures safeguards the victims of DVA and their (Home Office, 2018). However, thousands of DVA victims will suffer in silence if the information is not cascaded to BME women. Additionally, these women usually feel like disclosing DVA will compromise their opportunity for a better life (Anitha, 2011; Burchill, 2011; Randell et al, 2011).

One of the main issues, a social implication problem that has emerged from these pieces of literature due to BMEs’ status as immigrants is the lack of employment. Immigrants have been shown to lack the ability to access employment opportunities compared to their white counterparts. The lack of employment means having limited finances. With the lack of employment and limited finances, the situation becomes worse for women living with violent and abusive husbands and families. They can neither access health services nor seek, for instance, legal help, due to their inability to pay for these services. Hage et al (2010) have, for instance, mentioned the lack of proper information concerning their rights. This is because these women lack the finances or employment opportunities through which they can access critical information pertaining to their rights and how to get the necessary help to stop DVA. Furthermore, these authors opine that such issues are also exacerbated by institutional racism in the UK, where whites are preferred or prioritised for employment, essential services and other critical needs like accessing services when experiencing domestic violence and abuse. The result of such problems as noted by Anitha (2011) is that BME women are often isolated and cannot find the help they need to stop the violence. They continue to suffer from abusive husbands and from community or family gossip for many years without finding support.

Sub-theme: 3 – Fear

From the thematic synthesis, fear as a sub-theme falls under the main theme of BME women’s perception of domestic violence and abuse. The works of Wellock (2010) and Das (2012) highlight this problem succinctly. Fear amongst DVA victims encompass the fear that they would not be believed by professionals, fear that their children will be removed from their care by social services, fear that if they disclose it would result in further violence, fear of consequences it might have on their immigration status (Rose et al, 2011). Similarly, Burchill (2011) mentions that women felt leaving their matrimonial home will bring shame, embarrassment to their family. Furthermore, the BME women would remain in abusive relationship due to fear of becoming destitute and not being able to fend for their children. Therefore, BME women perceive the benefits of seeking help and leaving the abusive relationship might be outweighed by the risk (Randell et al, 2011). In addition, BME women believe that their husbands have the right to beat them (Burchill, 2011).

For black and ethnic minority women, particularly immigrants, they have normalised being beaten by their abusive and violent husbands. Most of them come from cultures where women remain submissive to their husbands and stay at home taking care of children and house chores. As a result, they are afraid of going against this norm and would rather persevere and live with such suffering to keep their homes and families. Furthermore, evidences by Wellock (2010) and Das (2012) in the UK indicate that family honour is very important for most individuals in BME groups. Saying something that can go against or harm family honour is highly prohibited. As a result, these pieces of evidence suggest that women keep quiet about their abusive husbands to keep family honour. These authors also opine that BME women and their families do not like being gossiped about by the community or other family members. Exposing oneself to the public, for instance, by reporting about abusive husbands becomes the talk of the community and neighbours and it becomes highly stigmatising. The women going through DVA in the United Kingdom, therefore, prefer keeping quiet about their suffering in domestic violence and abuse from their husbands to being gossiped and going through stigma that might result from reporting their family issues to the authorities.

In most ethnic minority groups, especially because of the culture of their homes countries, honour is associated with the sexual behaviour of a woman. Therefore, deviations from the established sexual norms is considered dishonourable or disgraceful to the whole family. Other countries also consider intimate partner issues, violence or abuse taboo subjects that cannot be taken out of the family circle. In these cultures, it is very disrespectful to report abuse, especially sexual abuse by a partner. This is the case in countries like Nigeria and Jordan (Bessa, Drezett, Rolim and de Abreu, 2014). Pakistan, for example, also consider divorce a shameful act which society cannot accept (Hadi, 2017). Based on these cultures, women are abused sexually, physically and emotionally, keep these problems to themselves or within their families, and do not seek extra-familial help. These happen for immigrant women in the UK who experience such challenges but remain silent with their issues because of their cultures and social norms that promote protecting their family honour at all cost (El Abani and Pourmehdi, 2021).

These arguments are supported by Guerin and de Oliveira Ortolan (2017) who say that there are patriarchal societies all over of the world where it is acceptable that men have the right to punish their wives through physical methods. According to Guerin and de Oliveira Ortolan (2017), this is the case for ethnic minority women in the UK whose origin is a country like Ghana where men can chastise their women physically. Similarly, Hussain et al. (2019) note that this attitude is also found in the Japanese culture where women and men of all educational levels and classes agree or accept that wives can be battered by their husbands. According to Mojahed et al. (2020), many women experience violence from their male relatives or husbands in Islamic countries. In these countries, physically punishing your wife is even allowed in religious texts and is institutionalised as a social norm (Mojahed et al., 2020). Therefore, women from these cultures and similar cultures in different parts of the world, who live in the UK, have continued to go through domestic violence and abuse because in their cultures, being punished physically by a husband is normal.

According to Ingram (2016), domestic violence and abuse is a serious problem and threat in societies and cultures that are already under duress because of the lack of education, opportunity and because of extreme poverty. In this study, the researcher found a relationship between sexual assault and domestic violence against women in some communities with poverty. Kerr (2018) also found that among Native Americans, domestic violence and abuse were blamed on hardship and severe poverty. According to Necula (2020), most countries globally see and consider a woman as his husband’s property, especially with regard to the woman’s sexuality. These authors give the example of numerous women from a country like Bangladesh where they are beaten even to death with some being driven to commit suicide after being dishonoured by rape.

Supporting these claims are site who claim that there both service-related and structural barriers which prevent or discourage women from ethnic minority groups in Western countries like the UK from seeking help. These authors claim that many women in black and ethnic minority groups, especially immigrant women who have run away from their homes with their husbands due to life difficulties like war and poverty lack education. This is besides the problem of language barrier where communicating their issues in English is difficult. The lack of education means that these women remain ignorant to the understanding and knowledge of their rights and services which they can seek to stop their suffering. The lack of education and knowledge about their rights and how they can find help means that these women continue to suffer without knowing what to do. Their husbands also take advantage of this ignorance to hurt them because they know their wives will not be able to take measures against their actions (WHO, 2009).

Francis, Loxton and James (2017) also discuss about the cultural barriers that prohibit individuals from finding extra-familial help, particularly children and women. According to Francis, Loxton and James (2017), such cultures, especially those in ethnic minority groups who are also immigrants from regions where this is the norm, women experiencing domestic violence and abuse are afraid of the consequences of finding extra-familial help. Most often, looking for help within the family or from other family members and relatives yields no results. The result is that they continue suffering abuse and violence from their partners or even other family members. This is similar to cultures where the norms, particularly, traditional gender responsibilities and roles prevent males from taking part in DVA services or talking with others about their family difficulties. Consequently, men do not get the necessary advice or help in how the relationship with their wives can be improved to avoid violence and abuse. This means that women continue to suffer as they keep their challenges to themselves (Francis, Loxton and James, 2017).

The fear of women to report domestic violence and abuse is most influenced by social and cultural norms of ethnic minority groups (Messing et al., 2015). According to Messing et al. (2015), many cultures have reinforced a negative perception against women. For instance, there cultures where girls are seen as less valuable compared to boys. This is the case, for instance, in India where female children are perceived to have less economic and social potential. A similar situation is also seen in Peru where the girl child is not seen as important. Instead, they are perceived as instruments to be used in home labor (Messing et al., 2015). As a result, the freedom of women is restricted and they are treated in unaccepted ways like being physically assaulted and raped. Women from such societies already see themselves as being inferior to their male counterparts. They end up accepting the kind of treatment they get like being beaten or mistreated by their husbands.

NICE (2014) notes that there is a need to raise awareness on the impact of DVA and educate BME women in order for them to safeguard themselves and their families. Based on a report by NICE (2014), the government of UK should come up with campaign programs to raise awareness on stopping violence and abuse against women in BME groups. It is important for these communities, both women and men, to be taught the negative impacts of DVA on families, on women, on communities and the entire nation, as well as how to stop it. As noted earlier by Home Office (2019), women who undergo domestic violence and abuse usually loose productivity and cannot help to build their families in terms of being motivated to find employment and support their families. They may also suffer from health challenges as a result of the violence and abuse costing the government a lot of money to cover for their health. NICE (2014) thus called for increasing awareness and campaign against women in BME groups.

In contrast, Randell et al. (2011) identified fear in a different context, as an internal motivator for seeking help amongst DVA victims due to fear of the DVA getting worse and their children or themselves being hurt or killed. Randell et al. (2011) claims that for some women in BME groups, it becomes very difficult to persevere DVA and become fearful for their health and the safety of their children. As a result, they become motivated by this fear and opt out of abusive relationships. They, therefore, seek help from the authorities, disregarding all the social implications of being immigrants, and the likely consequences of reporting their bad experiences such as stigma or gossip in communities.

Impact of domestic violence and abuse on BME women

Wright (2017) has shown how domestic violence and abuse can have serious mental and physical health consequences on women. Indeed other researchers such as Wright (2017) claim that DVA can increase the risk of social and psychological problems, injury and even death. According to Wright (2017), domestic abuse, particularly psychological abuse, usually have more impact that is negative on women compared to physical assault. Heise et al. (2019) support this claim by saying that women suffer more from purposeful ignoring, jealous control, ridiculing, criticism and threats of, for instance, being harmed, destroying their personal properties, and abandonment compared to being assaulted.

Nikparvar et al. (2018) highlight some non-fatal outcomes that BME women who have experienced DVA have shown. Some women have acquired unwanted pregnancy from being sexually assaulted and raped while others have been infected with sexually transmitted diseases like HIV/AIDS. Other women have suffered from permanent disabilities while others have experienced miscarriages because of being physically beaten by their husbands (Nikparvar et al., 2018). According to Nikparvar et al. (2018), domestic violence and abuse have serious mental health consequences on women who experience it, especially those in ethnic minority groups who are already under the duress of poverty, lack of jobs and employment opportunities, and the effects of racism. Nikparvar et al. (2018) say that BME women who have suffered from DVA have shown signs of depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, eating problems, sexual dysfunction, obsessive-compulsive disorder and low self-esteem. In much serious situations, these women have portrayed suicidal ideations, experienced maternal mortality and even committed suicide (Yalch, Schroder and Dawood, 2017).

Conclusion

BME women are usually trapped in a cycle of abuse due to immigration issues, fear of being homeless and not being able to provide for their children. The normalisation of DVA among women who come from cultures and societies where being punished by husbands is normal and where women are seen as less valuable compared to men have led to increased suffering among these women. The result is that these women suffer serious physical and mental health problems and cannot or have no means to access help. Therefore, with appropriate DVA intervention and education on what constitutes DVA, BME women would be able to make informed decisions and seek help. HVs and other professionals who support children and families should be trained to identify DVA and being able to discuss with the victim.

Chapter 4: THE FINDINGS

Introduction

This chapter presents the findings of the review and illustrates how they address the aim and objectives of the study. The chapter also includes limitations of the integrative literature review and discussions on implications to health visiting practice. This integrated review was aimed at examining why BME women are reluctant to disclose DVA.

The findings of the review were discussed focussing on the four objectives of the study that were:

To examine the factors which influence the majority of BME women experiencing DVA not to seek help.

To understand the impact of DVA on BME women and their children.

To explore how HVs can encourage help seeking amongst BME women.

Finally, to provide recommendations towards improving policy and practice within health visiting and other agencies that support BME communities.

The Factors which influence a majority of BME women experiencing DVA not to seek help

All the studies included in the review examined the factors that influence BME women not to seek help. The results from the review suggested that there are various reasons why BME women find it extremely challenging to disclose DVA. Some of the discussed barriers include social and economic factors such as finances and the lack of employment because of their status as immigrants. The lack of employment and limited finances makes it difficult for BME women undergoing DVA to seek help or legal support because of their costs. Their immigration issues such the lack of proper immigration documents or Visas also discourage them from seeking help because of the fear of being deported back to their countries. These women are also afraid of gossip from their communities and the harming their family honour. These are worsened by the lack of awareness of their rights. As a result, some BME women continue to live through serious suffering because of DVA. The lack of finances and limited funds also means that these families live in poor housing and as such, lack community support influenced DVA disclosure (Anitha, 2011; Burchill, 2011; Femi-Ajao, 2018).

In addition, it was recognised that cultural beliefs and values play a major role in BME women’s decision-making on whether to disclose DVA (Wellock, 2010; Das, 2012). According to these authors, some BME women have normalised being abused and passed through violent treatment by their husbands. In their cultures and ways of livelihood, the husband is the head of the family and has a right to beat their wife. Women, on the other hand, take household roles and are supposed to remain submissive to their husbands. This normalisation of violent treatment and abuse means that suffering women do not seek help.

Burchill’s (2011) study also identified that stigma was amongst the cultural issues BME women face from their community if they make a decision to liver her husband. According to this author, women who participated in the study reported that they could not disclose their experience due to fear of being deported from UK, being destitute or losing their children and families.

The impact of DVA on BME women and their children

This objective was not fully addressed by the review. Das (2012) was only study included in the review that interviewed children, but the impact of DVA on the children was not fully addressed in the study. Obviously, we all know from research that it is very traumatising and upsetting for children to witness their parent being abused. There is a number of published research which have addressed the impact of DVA on children such as finding it difficult to concentrate at school, sometimes children become withdrawn (Devaney, 2015). DVA can have significant risk to the child’s long-term mental health and physical problems (CAADA, 2014; Manton, 2015). Children who witness DVA have a higher risk of being abused themselves, as they tend to normalise the abuse (Das, 2012).

How HVs can encourage help seeking amongst BME women