Family Presence During Resuscitation

Abstract

Background: Families present during resuscitation has been a current topic in clinical practice over the past twenty years (Paplanus et al., 2012). This is due to the increase in the numbers of families willing to be present throughout the event and with the ever-growing social media influx, they have outlined what they are able to do in hospital settings. There have been worldwide studies to look at the impact that such presence of familieshas on health care professionals and on their perspectives on families remaining in clinical conditions, however, little insight is available on this subject since few studies have outlined the effects of such presence on the families (LaRocco and Toronto, 2019).

Aim:Is to search and research the impact families have on witnessing resuscitation througha systemic review.

Methods: The Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), PubMed, Wiley, Google Scholar were searched to find relevant literature.Research between 2015 to the presenthas been utilised. Due to the lack of research on the family’s point of view,some of the papers were identified which have both views from both staff and family to help the author gain relevant insight into the findings.Six papers met the inclusion criteria and were criticallyanalysed using the Critical Appraisal Skill Programme (CASP) (2018) and McMaster (1998)toolkit and finding five key themes; Sharing information, staff’s attitudes, grieving, everything which had been performed and the psychological impact on the families.

Findings:The study has shown that the research does not have any robust information on weather families gain certain effects from witnessing resuscitation. There were a variety of views, and these outlined the necessity to conduct greater numbers of researches before implementing FPDR in clinical practice, due to the mixture of views from both families and staff perception.

Chapter 1 - Introduction:

The purpose of the systematic literature review is to look at the impact on family members while they could be present during Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) and the impact it has on while they witness it. There is increasing numbers of debates about the advantages and disadvantages of family members-witnessing resuscitation and the impact it has on them (Paplanus et al., 2012). This will be done by searching for relevant literature and critically analysing the obtained informationto find the impacts it may have on families witnessing the event of resuscitation. The overall structure of this dissertation will be organised into chapters outlining the introduction, methodology, findings, recommendations, implications and summary ofthe study.

Throughout this systematic review, confidentialitywill be maintained and no breach of the Data Protection Act (2018) would be undertaken and work would be aligned with the code of conduct Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) (2018) .

The controversial international debate of familieswhichcouldwitness CPR and the impact it may impartto them has been raised serval times;however, still, no concrete evidence has been published in the UK(Koberich, 2018). Althoughguidance has been published worldwide, The Emergency Nurse Association (2012)was published has since been removed and seen the procedure being left with no guidance available. However, The Resuscitation Council UK (2010) wrote guidelines on how families should be present if their children needed CPR attempts; but did not mention any guideline on adults. Although, when rewritten removed this section and stated they were waiting on newer research before publishing guidelines on FPDR (Resuscitation Council UK, 2015).

Nevertheless, local trusts have been producing their guidance on FPDR. However, this causes growing concerns with the limited research available on the procedure and the impacts on the families are not known and the trusts have not utilised the existing evidences as well (Miller and Stiles, 2009). However, with the little published literature available on the impact on FPDR, the context of this study wasfacilitated and the four pillars of nursing of Royal College of Nursing (RCN) (2018) were utilised to research and develop clinical practice.

In the 1980s, Doyle et al. (1987) reported two separate occasions of families demanding to be present during resuscitation efforts and see the family present during resuscitation (FPDR) programmesin America. Since this, it has seen health professionals express their views that it is too traumatic for families to witness and distract staff in facilitating the procedure (De Stefano et al. 2016).

By reviewing the UK in-hospital cardiac arrest report, the research hashighlighted that 16,210 patients needed CPR in 2018 (Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre, 2018). However, only 2%of families were able to witness their loved ones gettingresuscitated even though 94% expressed they wanted to be present (Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre, 2018).

In comparison, Lederman (2019) states thatwhen family members are present, they avoid doubting the actions of health professionals and stop expecting unrealistic efforts from the professionals to securethe lives of their loved ones. However, from the findings it could be discerned that they do not consider the detrimental impacts of the same which could be contradictory to those of the expectations of the families, this systemic review will go and see if the answers can be obtained to ensure thatthis controversial debate could be ended (Portanova et al., 2015).

In this systematic literature review, there will be a slight use of abbreviation to refer to specific nursing and clinical terms and these are outlined in the table below.

In summary, this chapter has introduced the topic of FPDR and has providedbackground information of how it was introduced into clinical practice. Chapter two will look at the search strategies used in finding the informative material required to see if families are impacted by witnessing resuscitation.

Chapter 2 - Literature search strategy:

This chapter discusses how the research was obtained from the topic summarised in chapter one. EBP comes from the integration ofresearch and obtained knowledge and has usedit to deliver excellent care based on the current, available, valid and relevant evidence (Ellis, 2019). With the continuous changes in healthcare, EBP needs to be adaptedand newer research has to be obtained to meet the challenging complex needs of the industry (Mackey and Bassendowski, 2017). However, the hierarchy of evidence has been utilised to rank the relevant evidence to seethe quality of their validity, design and applicability to patient care (Polit and Beck, 2017). Doleac (2019) expresses that the hierarchy of evidence triangle outlines a visual and systematic depiction of forms of research from the least reliable to the most reliablewhich is known as the “gold standard” (Ingham-Broomfield, 2016). It is essential to understand the quality of EBP that will be used to implement the change in practice to see if it is robust to rely on findings alone (Schmidtand Brown, 2017).

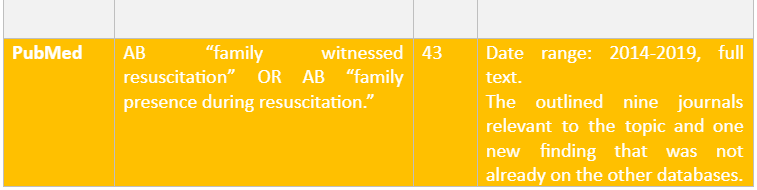

The study employed a comprehensive literature search utilising the university academics electronic database, to help obtain more considerable nursing literature and appropriate for identifying the effects of FPDR in the clinical area (Godin et al., 2015). The search was conducted between October 1st – 20th October 2019. The electronic search is essential in performing as the online databases are seen to have diverse and current information regarding any topic to help in executing the study in a successful manner (Dunn et al. 2018). The search platform which was mainly considered in executing the study was CINHAL, but the others such as MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, Wiley and PubMed was used in collecting information by employing the search terms established below. However, google scholar was utilised to see if any other research became available due to the limited research available on FPDR.

The research question in the study was formulated by using Population, Intervention, Context and Outcomes(PICO)framework (Bettany-Saltikov, 2016). The PICO framework is mainly used in evidence-based studies to develop the research question by enquiring about the topic of the study in details (Milner and Cosme, 2017). It implies the development of a clarified research question which could assist the researcher to understand the facts regarding the data which is required to be collected to resolve the identified problem in the study (Khan et al., 2003). Although there are many different frameworks, this framework is comparatively appropriate to the research question which requires to be resolved through qualitative research processes involving research participants from which their experiences and feelings could be obtained (Bettany-Saltikov, 2016). However, due to not having any context to the question and no comparison, the context was missed out in the PICO table and left with the PIO (Bettany-Saltikov, 2016). The table below outlines the PIO for this research and how the question was broken down. When the PIO outlined the main words and showed different words with the same meaning that could be used in the search to find a broader range of literature from using the Boolean search tools (Considine et al., 2017).

To help search the Boolean operators such as “AND” “OR” “NOT” were used for connecting the keywords highlighted in the PIO,to develop a proper search in collecting the required information (Bettany-Saltikov, 2016). As well as utilising “ and * to further produce more relevant results by expanding the search terms (Bozzano et al., 2006). While, utilising the reliable databases subject headings to provide further medical terms that may have been used to help retrieve the correct journals on FPDR (Bettany-Saltikov, 2016).

On searching the literature, sit highlighted limited journals being retrieved on family’s views, perspectives and the impact it had on them to witness CPR. However, there had been plenty of research facilitated on the perception of medical staff on their thoughts and feelings on families witnessing resuscitation. Below in table 2, shows the hit number of the different words used to facilitate the search and how many hits were found and which were relevant to the systemic review.

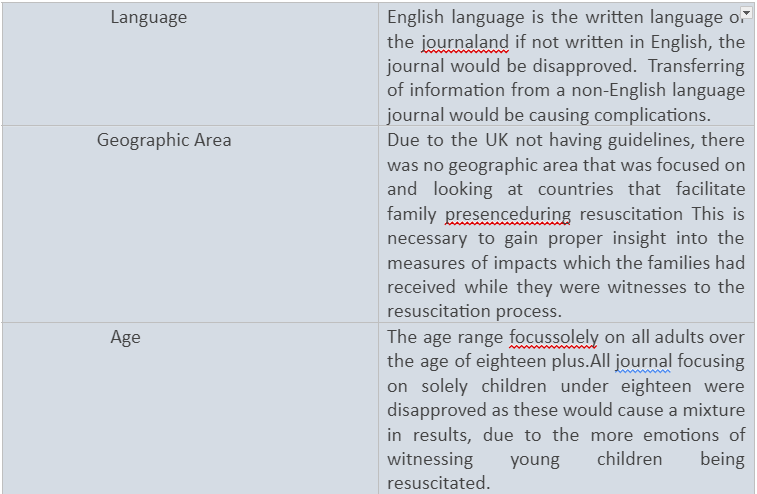

On the eighteen papers that were found, they then went through the inclusion and excursion criteria. The inclusion criteria inform the characteristics which are to be considered to perform the study, and the exclusion criteria are the factors that are to be avoided by the researchers to be considered in performing the study as it would lead to raising error (Doolen et al. 2016). The inclusion and exclusion criteria of the study are highlighted below in table 3.

After looking over the eighteen journals, it is seen that eight of the journals were not peer-reviewed and seen their relevance to the study to be inconclusive. Also, ten of the journals looked at the views of children, in which six of these were not peer viewed which were not relevant to the study (Parahoo, 2014). Due to the limited research on the subject,seen six journals left. To gain further information seen some of the previous journals with children and adults’ views in the same paper being used. However, only extracting data relevant to family opinions. By being aware of how this could be detrimental to the findings but being concise as there was not enough evidence to fulfil the systemic literature review and seen three of the previous finding placed back.

Making sure a non-bias approach was taken; this saw nine journal articles were narrowed down utilising the hierarchy of evidence table and picking the six papers that were more robust over the others (Daly et al., 2007). The remaining nine full-text studies were independently reviewed by hand reading the abstracts of the articles to make sure that these were compatible to the methods applied in the current study and were in line with the inclusion criteria as has been previously described (Bettany-Saltikov, 2016).As well as looking at the papers mainly focus was on the effects of family members witnessing CPR and their opinions. Also, making sure the articles were from different literature sources to have well-balanced research selections and making sure they were robust sources (Heaton, 2008).On looking at the hierarchy of evidences, two journals were eliminated these were related to literature review processes and were not of the gold standard which had been needed (Ingham-Broomfield, 2016). By evaluating the articles found from reading the texts thoroughly and filtering out any irrelevant articles, by reading the full articles seen the final six papers being obtained.

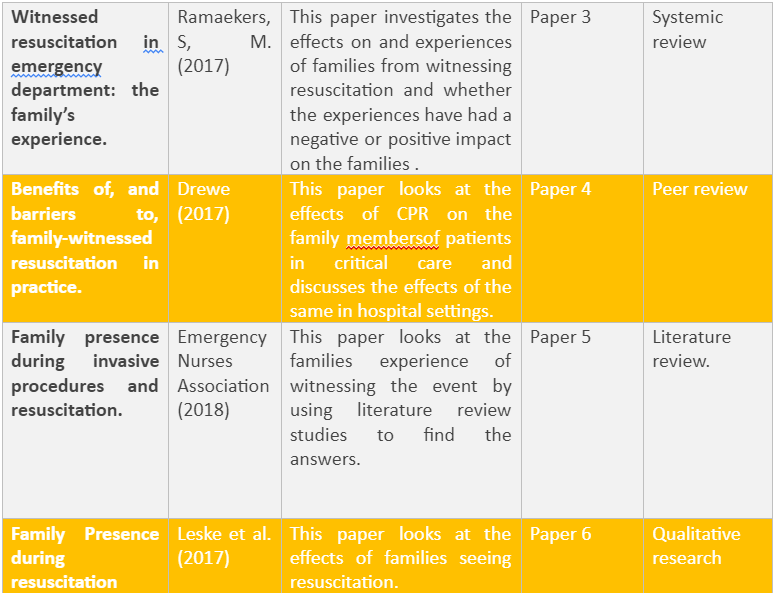

Below is a table of the journal articles that were picked to be critically analysed and formed the final six papers.

From the six papers being obtained from the above systemic search, will now be critical analyses in the next chapter.

Chapter 3 - Literature Review:

The systematic review was to analyse each of the six of the journals to highlight the key themes. The findings highlightedfivekey themes which are highlighted in the table below in which the themes have been related to the individual points of the study.The themes that emerged from across all papers were strong and apparent throughout each paper. Fromappraising the quality of the research by critiquing the evidence using the CASP (2018) and McMaster (1998) it was found how reputable the researchwas. The CASP (2018) toolkit was used on the random control trials, systematic reviews and qualitative research. However, McMaster (1998) was used with quantitative research as it was better suited to evaluate this type of research.

Before discussing the key themes, it was noted throughout all papers that it was not stated if the resuscitation attempts had been successful or the patient had passed away. Flaws have emerged from utilising a conflicting populationsample and mixed viewpoints have been obtained from the different outcomes of the events (Polit and Beck, 2017). Herbert (2013) outlines from having an improper selection brings forth chance of havingjudgemental and biasedfindings from not obtaining a randomised research sample . This meant that limitations could arise from the research using flawed assumptions to base study arounddifferences in the views and of the families outlining confounding factors regarding the subsequent effects which the families would encounter (LoBiondo-Wood and Haber, 2017).(Šimundić, 2013).

In comparison, from the deficiency of research available seen some of the studies have mixed opinions of health professionals and families andhaving to extract information solely from thefamilies viewpoints, which potentially could see implication throughout (Coggon et al., 2003). Meaning it may see the validity being conflicted encase there is a mixture of views being placed together, but being cautiousabout collecting only the families viewpoints with the possibility of combination of views (Moule et al., 2016).

Similarly, as there was no research available from the UK and was all from other overseas countries seen that the findings or information, they provide may not be able to be transferable to the UK laws and policies. Due to having the UK having regulatory bodies that all health professional need to abide by their professional standards could see implications for their work conduct (NMC, 2018). Equally, after reviewing all papers, it highlighted that all findings have only been conducted in either emergency departments or intensive care units, as described they are the only areas with experienced staff to utilise the event. From the findings, it wasoutlined that specific area based focus had made transference to other hospitals improbableand would not be robust to other areas outside that of critical care (Gelling, 2015). The potential of research bias exists since the authors could express various viewpoints in unsubstantiated and unsupported manner and without stating the possible sources of such observations along with inadequate randomisation of the research outcomes(Fain, 2017).

Sharing information:

All papers outlined that families view themselves as a value to the team by being able to provide the health professionals during the event with vital information on their family medical history of the patients as they are their family members, current medications, health conditions and allergies. Currently, the NHS Constitution (2015) promotes health professionals to work with services users and their families to make care person-centred, while not excluding people and to value all information which could beprovided. However, it does not state that the information was acknowledged by the health professionals but states later on that families caused a distraction to all health professionals during their resuscitation attempts from having to listen to both information and communicating with other staff on the procedure (Langbecker et al., 2013). Papers 1, 2, 5, and 6 expressed they felt that they were compromising patient safety and were unaware of their expected roles in this situation on supporting the families while their loved ones were under treatment. Salmond and Echevarria (2017) state that having policies and procedures help professionals know their specific responsibilities associated with their role would be assisting in the improvement of the patient care and would prevent the professionals from having to experience certain complications involving the limitations to their training. The NMC (2018) highlights that all nurses must not work beyond their limitations and completing all training to provide them with a competency that is needed to fulfil their job role or they will be working against their professional conduct.By outlining the importance of guidelines and procedures being developed to understand their expected roles and not going against their work ethics. Kodama and Fukahori (2017) highlight policies which are produced by wards through personal interpretation of the task and no utilisation of the evidence-based practices take place. This means that serious and negative implications could arise and no consistency could be achieved which could see families and patients being placed at risk and open the trust to litigation.

From critically examining the papers, it showed papers 4 and 5 had no methodology on how they had retrieved their findings and no clear aims on what they were trying to achieve their explanation in their title. It is crucial to have precise methods in research to help design the research and toprovidethe information the reader needs to judge the authenticity and validity of the study as well as that of the data collection process(Hammarberg et al., 2016). Meaning potential flaws in the research and papers 4 and 5 being subjective to being bias as it was identified as an expert’s opinion and not robust and trustworthy source of where they had gathered their research from (Parahoo, 2014). Additionally, these views from both papers could have been from having a good experience of families being present during resuscitation and outlined their personal experiences and other experiences had not been gathered to explore further findings (LoBiondo-Woodand Haber, 2017). Additionally, paper 2 utilised quantitative research to help gather their findings, since the research involved extensive robustness, it was not difficult to gather the correct information from having open-ended questions to gain further insight into the benefits in presence of family members during such procedures (Boswell and Cannon, 2018). Cresswell et al. (2003) states from the use of mixed methods research that open-ended questions could explore the nature, and offer the researchers with rich, qualitative data as well as utilise quantitative data . Significantly, the research would assist the researcher to gain sufficient insight into the opinions of the family members who could be present during the procedures of resuscitation to measure the derived benefits of such an undertaking (Cresswell et al., 2003).

Similarly, paper 3 and 1 express that families felt that sharing information had an impact on the success of the resuscitation attempt, as well as knowing they did everything which they could to help during the resuscitation attempted. In agreement, the professional standards outlined in NMC (2018) specify that all nurses need to work in partnership and respect all the contributions which could assist with effective care delivery. Camp-Gibson et al. (2016) concur, declaring that families providing adequate information to health professionals enable the feeling of being a valued member of the team and an advocate for the patient.

Likewise, all paper excluding paper 5 summarised that families were able to talk to their loved ones while being resuscitated and furnished them with the information on what was happening to them during the event to provide reassurance. The research papers have signified that the families had a positive impact from being present during the event and distracted them from the interventions going on around them (Fain, 2017). However, since reliable findings have not been consulted involving proper surveys through appropriately developed questionnaire, the subsequent outcomes published in this context by researches have been invalidated as well(Parahoo, 2014). Another flaw was detected in papers 2 and 6, were their participants were reduced over half after the families witnessed the event and refused to be a part of the trial and retracted their participation without explaining why. This indicated that itwas not possible to investigate the significance of the results due to not knowing if the participants were negatively impacted by witnessing the event and if the remaining participants had only positive perceptions (Johnson, 2019). It highlighted that the random control trials were no longer rigorous, their methods were no longer transparent and implications to the paper’s findings could have been obtained from not being randomised no more (Parahoo, 2014). Pararhoo (2014) explains these papers could have been more robust if these had explained in the methodology sections the reasons behind a large amount of participants dropping out from the research. The researches were required to highlight if the event had any effect on the family and justify the evidence through considering the same in the findings of the research (Parahoo, 2014).

Finally, paper 1, 3 and 4 indicated that the family were able to share information to other family members on the procedures through recollection of the events to others who were not able to attend and such efforts assisted them with understanding the process with nonmedical jargons. Braine and Wray (2018) agree by stating it helped by sharing the experiences with other loved ones and brought them closer together, instead of a health professional explaining and having no connection with the patient. Abbaszadeh et al. (2014) adding further that having family members able to discuss the event, saw the breaking bad news calmer and saw the family members taken control of the information sharing and reduce the stress to the health professional during the difficult time. While Mackie et al. (2019) express by having a more personal focus and helping with the family come to terms what had happened with the help of the family members that have been presented to reassure others.

Staff Attitudes:

Even though this study is looking at the family’s perspective, it was expressed throughout all papers that they felt staff attitudes affected their time while being present during resuscitation. Wendover (2015) expresses that staff attitudes have prevented the implementations of FPDW and have eliminated evidence-based practice to design innovation to change practice from their personal views. The NMC (2018) outlines that staff need not let their values and personal views jeopardise care delivery to service users. In agreement, Aitamaa et al.(2016) state that nurses must understand their own values in order to practice ethically and not to let their own views influence decisions and actions to deliver care safely. As outlined in papers 1, 3 and 5 found that nurses did not uphold their code of conduct (NMC, 2018) and made families feel unwelcome and did not want to support the procedure and expressed their own views on the situations. Meaning there were ethically flaws in the research from the authors not looking at any ethical implication that the research may entail and any consideration that would have to be implemented (Waycott et al., 2017). This signified that the importance to adhere to ethical principles in order to protect the dignity, rights and welfare of research participants (World Health Organisation, 2011).

Likewise, it hasseen for staff attitudes to changes a promotion in leadership needed to be utilised. Barth et al. (2016) highlight that leadership needs to be revised to see the impact of changing people’s beliefs and attitudes to see it reduce the interference of care delivery from changes being maintained. Leadership can help adjust staff attitudes that need to be adopted by all health professionals to see innovations being promoted and changing to promote better care delivery (Curtis et al., 2011). Huber (2017) state that due to the lack of training, guidance and organisational support staff do not pay attention to the procedure of FPDR . As it has become a taboo subject among health professionals from their professional standpoints the subject has seen them portray negativity on the procedure and placed their views and opinions which has seen families feeling unwanted (Rattrie, 2013). Looking at the transformational leadership style to help individuals to adopt to organisational change and influence as well as motivate the changes in practice by making staff aware of the findings and enable change in staff morale (Bommer et al., 2004). However, before this can happen, new clinical research on the subject needs to be produced in a transferable manner so that the same could be acceptable to all areas to measure if there is an impact from families being present during resuscitation. Also, making sure that their findings are valid, reliable and applicable to support all health professionals on what could be best regarding the current evidence-based practice (Gerrish and Lacey, 2010).

Wendover (2015) highlights that without the application of proper procedures and policies, staff allocation throughout the health mechanisms could become tenuous since staff members could become unwilling to place their registrations at risk due to absence of proper knowledge regarding the methods of facilitation of such events. Also, personality traits and value would be brought to the surface and this could result in depriving patient’s families of sufficient emotional support as the absence of knowledge of how to maintain professional support could be the most significant obstacle in this context (Wendover, 2015).

Nonetheless, limitation of the findings could be seen due to existence of bias from personal beliefs and values which have been highlighted in papers 1 and 4 which could lead to false impression and conflict between the accurate findings (Parahoo, 2014). Also, papers 2 and 5 did not outline any clear aim regarding the projects and did not justify for the utilised sampling strategy, as well as not mentioning how they did any of their methodology (Gerrish and Lacey, 2010). Aims are essential in research to outline the knowledge and understanding which is needed in order to answer the research questions (Doody and Bailey, 2016).

Grieving:

All papers found that FPDR found it assisted with the acceptance of of the families involving the situation of their loved ones and provided them with closure to help with the passing. McGahey-Oakland et al. (2007) stated that families knowing that they passed away with loved ones present and not left alone with strangers, allowed them to feel comfortable and bring a sense of what had happened. However, several authors disagreed that produced research stated that the grieving process was more traumatic from that of FPDR and the presence of family members ensured that such personnel would be suffering from extensive implications of their acquired experiences (Compton, 2011; Rose, 2018; Sherman, 2008). This could counter the research bias through a combination of differential research findings. .

Papers 1, 2, 3 and 4 did not specify their population they were aiming at even though it was highlighted at the beginning it was looking into adults only. However, from reading each paper, it showed that they had abstracted findings from other papers that had a mixture of population and did not highlight this as a contradiction in their findings and how they abstracted the sole information to be adults (Parahoo, 2014). Signifying limitations to the research, they utilised to base their current findings, as well as using not peer-reviewed research to base their finding saw the research being weak and not robust enough to change current practices (Poilt and Beck, 2017). By having a clear population helps understand the leading focus group and help readers understand the preferred target group so as to effectively transfer the knowledge gained from the findings to the same population (Tappen, 2016).

Everything was being done:

All papers except paper 6 allowed families to feel confident that everything was done to assist their loved onesregarding FPDR through witnessing the efforts of the health professional. Kennedy et al. (2017) voiced that families feel that health professionals try harder when family members could be present during the procedure. Due to the research, the findings from the health sectors of USA outlined the limitations to the findings due to the USA having higher litigation claims compared to the UK (Woo et al., 2017). This brings into perspective that in the USA, they have FPDR to show families that every effort had been undertaken to prevent litigation claims being put in place from them not seeing the event (Jabre et al., 2013). This has attested to the relative weakness of the research performed overseas when the outcomes of such research are required to be transferred to the contexts of the UK from having different laws and procedures, from that of the country of origin of the research based data. (LoBiondo-Wood et al., 2017).

From the family members observing the teamwork and the delivery of care that was being upheld, saw the families having a positive effect on being present during resuscitation efforts. However, there was no structured way into how they obtained these findings in papers 3, 4 and 5. Meaning it saw failings in the reliability, as it is essential to outline how they obtained the answer to help make the research robust (Parahoo, 2014). These saw the findings in these papers being possible bias from an expert point of view from not stating how they found the answer (Moule et al., 2016).

Psychological impact:

Interestingly, papers 4 and 5 results presented that families who were present during the resuscitation were less likely to have psychological issues such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression and anxiety over the families that did not attend. However, papers 3 and 6 have outlined that that families experienced unpleasant memories from the event but did not explain this further but stated that they regretted their decision in being present. These both saw a difference in retrieving their findings, papers 4 and 5 did not have any methodology and was using expert opinions, while papers 3 and 6 retrieved their information three months after the event to see if the event had any psychological issues had arisen (Gerrish and Lacey, 2010). From information which has been obtained after the event, the findings have been derived understanding about probable issues . However, papers 3 and 6, which had earlier stated that half of the participants had retracted their participation, have further led to believe there were potential flaws in the findings as these were nonrandomised (Parahoo, 2014). Meaning, from having an unrandomised focus group could see the findings being biased from only having a positive experience in the participants from negative impact being in the families who dropped out from the trial (Tappen, 2016).

From the inconclusive results regarding the research on the suppositions of FPDR causing psychological issues, the resuscitation Council (2015) has withdrawn guidance on the procedures and no further health institution has provided guidelines due to the incomprehension of the procedures. Nevertheless, papers 4 and 5 have expressed that families who were not present in the resuscitation and seated in the waiting area often see increased anxiety and stress disorders from the unknown of what is happening. However, the findings did not state how they retrieved this information and had not conducted or did any literature reviews themselves to obtain these results and saw the evidence as weak (Parahoo, 2014). With paper 5 expressing they re-interviewing participants one year later but had not a methodology or what method was used to gather the information from questionnaire, interviews, showed that there was no reliability to the findings (Cormack et al., 2015). Munhall (2012) state that the research methodology is the specific procedures or techniques used to identify, select and analyse the literature used to help with the findings, this will help identify the reliability of the paper by showing how the author came to the answer from their selected findings. Besides, the research found by papers 2 and 6 stated participants that initially agreed to be part of the research withdrawn and did not explain to their reason behind this and could potentially see anunrandomised controlled group (Fain, 2017). It could also see readers interpreting that it was detrimental to the family as they wished to not be part of the research after witnessing the event and had psychological implications with them not wanting to relive the experience (Johnson, 2019). From the research not being trustworthy has seen that it has seen the finding on families psychological health after witnessing CPR events being inconclusive from the lack of relevant and well-researched information being produced (Parahoo, 2014).

Additionally, all papers stated that health professionals had the ability to decide whether the families had the psychological ability to witness their loved ones being resuscitated. However, there were no details about how they examined or detected if the family members had psychological impairments and would be able to manage the event. This was outlined in the bias opinions of nurses who utilised their perspectives of being health professionals to make judgements on family members and could have extensive impacts on the families and this could facilitate the lodging of litigations from wrongly accused family members regardingpsychological health issues (Polit and Beck, 2017). However, Jabre et al., (2013) state all families have the fundamental right weather to decide if they want to be present after understanding of the event they are about to be subjected to and giving verbal consent. No judgement should be made off any health professionals. However, due to no procedures being produced it can be seen that health professionals can utilise their own opinions on how they evaluate the family and their ability to handle high-level psychological events (Jabre et al., 2013). The NMC (2018) states that all nurses must follow all policies and procedures in maintaining patient safety and to protect themselves from not carrying out any procedures which have not been supported with evidence. Due to some nurses assisting in the family being present clear guidance needs to be produced for them to maintain the accredited standards and know-how to manage and assess family members appropriately (LaRocco and Toronto, 2019).

While Paper 1 and 3 found families who attended suffer no psychological impact. Nevertheless, these findings were obtained straight after the event. They did not provide time for participants to absorb and reflect on the impact of witnessing the event and could present inaccurate result from being in a state of shock or denial (Burns, 2018). New research requires to be obtained on the prospects of exploring psychological implications to design new research strategies around these to develop greater transparent outcomes to assist with finding the answer (Parahoo, 2014). Then, such researches could be utilised to develop the nursing practices and to improve the outcomes further involving the quality of care services as per the NMC (2019) standards of proficiency.

From all of the papers, it showed that all research on the impact to FPDR was weak and all had limitations to their methods and needed further research before changes could be implemented into practice from robust evidence-based practice (Gerrish and Lacey, 2010). Moving on to the next chapter discusses the recommendations from the findings.

Chapter Four – Recommendation:

From the previous chapter, it has shown the effect’s resuscitation has on families and outlined that several recommendations needed to be implemented from the key theme that arose. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2015) states that addressing recommendations can identify gaps and ensure the development of the research in providing safe and effective care.

One of the recurring recommendations that emerged from all papers and outlined in chapter one was that there is no policies or guidelines published. The implementation ofpolicyin practice to support and guide both staff and families. To help overcome the current barrier, O’Donnell and Vogenberg (2012) highlight thatpolicies and procedures will provide guidance, standardisation, structure and consistency in clinical practices, and will reduce the risk of harm or safety to everyone in the clinical area. To address this issue, clear policies need to be made from the development of evidence that newer research will find. Meaning family principles will guide it and hopefully will reduce any mistakes during the eventand supporting their physical and psychological needs. All nurses have a duty of care to work within are limitation and providing the best possible care (NMC, 2018). By having a policy and guidance in place will see health professional working to the standards set to and providing excellent care.

The International Emergency Cardiovascular Care and Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Guidelines (Cummins and Hazinski, 2000) state an establishment of a policy will support the needs of the family members during resuscitation to maintain consistency throughout all clinical areas so to deliver excellent care during a difficult time. To help create the policy, national guidelines need to be produced when research is developed, and outlining the role descriptions and training to specifically to support families during FPDR and to promote the new policy for all staff to be aware of the changes they are implementing(Sak-Dankosky et al., 2019).However, before a policy can be implemented more robust research needs to be obtained to see if it is beneficial and if there are reliable findings on the effects it had on families though reliable, evidence-based practice. From having a policy will see staff being aware of their role throughout the procedure and reduce the risk of litigation and from not working outside their limitation and see safe practice being maintained throughout (NMC, 2018).

Another recommendation that surfaced while analysing all papers were staff’s attitudes were affecting the family’s experiences or even prohibited them from being present. To combat these findings, leadership skills need to be highlighted and developed in all nurse roles to be maintained in clinical practice (Bakari et al., 2017). By providing nurses updates to their leadership skills and making them aware of how their current behaviours and inhibition to change can affect patient care delivery systems outcomes (Dougherty and Lister, 2015). By providing education and team meeting sessions on leadership changes and maintain excellent standards will promote best practice through current evidence-based practice and will see nurses motivating and each other to clinical practice (RCN, 2020). As well as updating nurses, leaders need to be appointed and look at adapting a transformational leadership approach to work with the team to identify the approaches to adopt a successful change, while creating a vision to guide the change through inspiration and motivation (Hawkins, 2017). This will see nurses adapting the new procedures, as well as providing a staff meeting for them to express their current feelings but addressing DeBono (2017) six thinking hats to look at all issues in a positive and approachable way. While coming up with solutions into how they can support families during the sensitive procedure and see staff expressing their techniques to see the staff attitudes become more open on the procedure.

Within the grieving theme, several recommendations emerged relating to staff needing to be trained and educated to support the family emotionally and being able to provide them with information. Education is necessary to be addressed for the staff to obtain knowledge on how to overcome such a sensitive procedure with the correct guidance (Dwyer andFriel, 2016). To overcome the education, by looking at different teaching methods and finding which one will work best to address FPDR and encouraging the inclusion and build further methods and designs to address the target audience(Chen et al., 2017). However, on delivering FPDR training, it will have to depend on the resources the organisations can provide due to their training facilities and adapt it to their needs of the procedure (Toronto and LaRocco, 2018). It is therefore recommended that all of the hospital trusts are required to constitute educational training programs for their workforces to help meet the current standards which could be also in line with the NMC (2018) standards of practice.

Similarly, whenever newer research has been obtained and when such researches have been successful, to look at implementing into student nurses academic program to see it being able to be addressed in classroom settings where they can practice during simulation sessions (Chen et al., 2017). By introducing this concept early on in student nursing education, will increase confidence and comfortability will be obtained (Powers, 2017). Additionally, by allowing role play and scenario-based exercises in the university will prepare all student nurses for real-life situations and promote a more positive mindset toward FPDR (Powers, 2017). However, due to the research implications and unknowing, if FPDR is essential to the grieving process, further studies are required to focus on the development and validity of the development of FPDR (Parahoo, 2014).

Several themes emerged relating mainly to positive psychological effects but did note that it did affect some families. To help investigate a deeper understanding and find more reliable research, more structure and randomised controlled trials need to be obtained to seek the validity of the research (Politand Beck, 2017). Tingen et al., (2009) highlight that nurses need research to help them advance their field and understand the importance of the procedure and utilising it to better patient care delivery in providing optimal nursing care. Meaning, nurses can utilise the newer evidence-based practice to directly impact the care provided to all families while witnessing the events to make it as pleasant as it can be. However, all psychological impacts need to be reported in future studies to help build on how it will be maintained while using an experimental design that needs to study the shortand long‐term effects of FPDR on families (Toronto and LaRocco, 2018).

All nurses have a duty of care to care for both the patients and their family members and the research has highlighted that nurses are trying to protect families from witnessing traumatic events (Leske et al., 2017). Consent of the families would be required to be gained before the procedure to help them understand what they are going to be witnessing and the procedures. Signifying, the family having an insight into what they are about to witnesses as well as gaining consent on their contribution to further research in them expressing later if it had any impact on them. Meaning that several nurses dedicated to research need to be appointed and looking at how they will structure their research as well which methods they will take to make it robust while addressing limitations (Parahoo, 2014).

From the recommendations, there will always be the implication of how it would affect adult nursing. Below is a table of the explicit recommendation of what this chapter has outlined as key recommendations. In the next chapter will outline the challenges of making the recommendation in practice.

Chapter Five – Implications for Adult Nursing:

The study of the previous chapters has suggested that recommendations have to be developed regarding the implications of the same on adult nursing.Implications for the nursing practices involve discussing the findings and what thesecould entail for individuals who work in the current area of the study (Annesley, 2019).

One of the primaries findings outlined is that there needs to be newer research obtain. Meaning it could see the cost and timing of the newer research is acquired. However, it needs to see if the clinical budget will be able to facilitate the trail and discussed if it can be afforded (Huber, 2017). If unable, it could see implication on researchers trying to utilise other countries findings from utilising different laws, policies and procedures (RCN, 2019a).Curtis et al. (2017) outline that translating research into clinical practice is challenging but needs to be valid in improving patient outcomes from other findings from their evidence-based practice. Meaning, accurate translation of their findings to adapt it to the UK govern policies and in line with the professional code of conduct (NMC, 2018). Also, making sure hospitals do not make their own hospital base policy, as it could see the policy being based on weak evidence-based practice from their own clinical research (Toronto and Larocco, 2018). As this process could outline that certain mistakes could be occurring such as families not receiving the assistance consistently regarding the national guidance measures which would be required to base their policies on.

Likewise, a policy needs to be published to see families and staff know what is expected of them while receiving the correct support during a sensitive time. However, producing a policy will see the need for newer research to be conducted. For research to be conducted is trying to get the patient’s onboard to being part of the trail and talking about sensitive issues who may not have thought of dying (Toronto and LaRocco, 2018). It may cause difficulties to obtain newer research from the inability to randomised FPDR due to the unpredictability of the event happening and not having the resources in place to abstract the data (Leske et al., 2018).As well as gaining consent off families to relive their experience later down the line when they want to forget about the experience, if not successful (Fiori et al., 2019). The systemic review could as well highlight the fact that the particularised behaviour of the participants involves their unwillingness to be involved in the research data collection process (Parahoo, 2014). Also, the cost of having extra staff on the ward to conduct the research and not being able to predict if a patient is going to go into cardiac arrest are also significant obstacles. From the current staff, shortages may see it hard to obtain research nurses from taking them from other wards that are currently struggling in the staffing crisis (RCN, 2019b). However, making staff aware, that they cannot perform FPDR. At the same time, the research and policy are being implemented, as it is opening to litigation claims from going beyond their work limitation (NMC, 2018). As well as being aware of cultural implication when carrying out the research and considering all particular settings and how they will be adapted to (Masuda, 2017).

Similarly, while educating the staff, they need to look at which education method would be beneficial for the staff . However, both classroom and e-learning packages will increasethe cost of the NHS in implementing such processes into practices. However, when designing the training, one needs to evaluate the effects on the learning and addressing of the key points. Powers (2017) outlines that professionals obtain greater information when they have eLearning training course based direct lecture sessions. Before the design of the training package needs to be facilitated, understanding which programme is better suited to their clinical environment would have to be performed (Johnson, 2019).

From facilitating leadership skills to practicing the trainings derived from the teaching session, FPDR has been attempting to maintain the procedures. However, trying to have the time to take all the staff off the ward to have an update and making sure all staff could attend would require multiple sessions to be put on to address leadership. This has outlined the fact that the trust would be having to pay for multiple sessions, as well as staff levels would have to be reduced while the time of the training session would be facilitated. As the RCN (2019b) outlines the current staffing shortage and how the management would facilitate these sessions. Additionally, Yukl (2013) highlights that staff may not be aware that their leadership style needs to change and may see reluctant to change. This is were change theory needs to be looked at and seeing with a theory is better suited to help get people on board, e.g. Lewin’s (1951), Roger’s (1983). Meaning that the change is the driving force and assigning leaders who will push employees in the direction of change and see it implemented correctly (Yukl, 2013). The only issue is the resistance of employees who do not want to propose the change and these need to be looking at their personal attributes as to why they do not want to apart to the change (Henriksen, 2020).Also, by assigning leaders to help keep the staff motivated, will see the leaders having to take time out of their regular role and may need the trust open up new nursing jobs to maintain adequate staff levels and maintain safety (RCN, 2019b).

Moving forward, it has highlighted that further research is required to be facilitated to make the recommendations in practical and effective in finding out if there is an impact on families when witnessing resuscitation. When valid, reliable findings are shown and these could further be utilised to undertake various other forms of recommendations, however, the implications of detrimental impacts regarding the clinical cost management, timing and implemented changes in the nursing practices would be required to be factored in within the future studies as well.

Chapter Six – Conclusion:

As outlined in chapter one, it showed that FPDR was a very taboo subject upheld in the clinical area, however health professionals were still proceeding with the procedure with no guidance on if it had any impact to the families witnessing. The present study was designed to determine the effect of family members being present during resuscitation. From the findings, it has revealed from the literature show it is very controversial among both families and nurses and other health professionals. There are still many unanswered questions and remain unsure if there is any implication to families witnessing the procedure due to the lack of research.

From utilising the RCN (2018) the four pillars of nursing credentialing criteria have been highlighted as clinical practice, leadership, education and research. Has seen all four pillars used to help with the systematic review to transform patient care by underpinned the four characteristics and performing them throughout the systemic review (RCN, 2018).It found that primary research needs to be obtained to provide clinical areas with robust evidence on what is the best practice so as to meet the clinical standards. As well as obtaining research solely from the UK to make it transferable to all clinical practice areas. However, the research needs to look at both the experience and the trauma it may cause in the future to the families and looking at revisiting the participants later down the line to make sure that the research is vital with no flaws. In future investigations, it might be possible to use a different approach and understanding it is a sensitive area. However, if families want to be present, they need to be a part of the research to help improve clinical practice as well as understanding how to support and maintain the procedure at the same time to excellent standards. Also, using a mixed study group from both unsuccessful and successful attempts to get a greater understanding and utilising mixed research with both qualitative and quantitative research (Parahoo, 2014).

Additionally, with new research being obtained will be able to see current implications or advantages and being able to utilise the findings and see if they want to facilitate the change and implant the new information into them polices to guide staff. Signifying, it will ensure more consistency throughout all clinical practice. It will help eliminate staff points of views and not lead nurses to make difficult decisions when there is guidance in their practice. Furthermore, due to the lack of a policy currently is leading to inconsistency to patient-centred care and the support of an establishment of policy being implement could prevent this from happening. Also, it will see if effective education needs to take place and if successful look at implementing it into academic practices for students to learn from the beginning of their training.

The outcomes and information derived from the systematic literature review would be disseminated to the Resuscitation Council (2020) along with the specialised research nurses so that knowledge about the evidence based interventions could be effectively transferred to the recipients as well. The intention is that such a process could carry on the research to further the findings and to determine the new research processes which could be discovered and associated knowledge could be transferred into the clinical practice (Curtis et al., 2017). The author would be utilising the professional development and adhere to the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) (2018) standards on sharing knowledge to identify gaps in care which would require to be attended to maintain patient safety and the management of patient family members.

Due to the current situation of the families wanting to be present while their loved ones are resuscitated, there needs to be more guidance and findings on the benefits of their presence in the room. As well as the impact it will have on them, and these questions need to be answered before placing them in this situation. Also, nurses need to be aware going forward of the risks they are performing if they are letting families being present from working outside of their limitation and going against their NMC (2018) code of conduct. Due to the question remains to be unanswered, the author will carry on in their professional body to research the implications and carrying on with the research proposal.

References:

- Abbaszadeh, A., Ehsani, S, R., Begjani, J., Kaji, M. A., Dopolani, F, N., Nejati, A., and Mohammadnejad, E. (2014). ‘Nurses' perspectives on breaking bad news to patients and their families: a qualitative content analysis’. Journal of medical ethics and history of medicine; 7(18).

- Aitamaa, E., Leino-Kilpi, H., Iltanen, S., and Suhonen, R. (2016) ‘Ethical problems in nursing management: the views of nurse managers’. Nursing ethics; 23(6), pp.646-658.

- Annesley, S, H. (2019) ‘The implications of health policy for nursing’. British Journal of Nursing; 28(8): pp. 496-502.

- Bakari, H., Hunjra, A, I., and Niazi, G, S, K. (2017) ‘How does authentic leadership influence planned organisational change? The role of employees’ perceptions: Integration of theory of planned behaviour and Lewin's three step model’. Journal of Change Management; 17(2), pp.155-187.

- Barth, J, H., Misra, S., Aakre, K, M., Langlois, M, R., Watine, J., Twomey, P, J., Oosterhuis, W, P. (2016). ‘Why are clinical practice guidelines not followed?’ Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine; 54, pp. 1133-1139.

- Bettany-Saltikov, J. (2016) How to do a systematic literature review in nursing. 2nd edn. London: Open University Press.

- Bommer, Rubin, & Baldwin, 2004

- Boswell, C., and Cannon, S. (2018) Introduction to nursing research. 5th edn. Texas: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

- Bozzano, M., Bruttomesso, R., Cimatti, A., Junttila, T., Ranise, S., van Rossum, P., and Sebastiani, R. (2006) Efficient theory combination via boolean search. Information and Computation; 204(10), pp.1493-1525.

- Braine, M, E., and Wray, J. (2018) Supporting families and carers: a nursing perspective. Raton: Routledge.

- Camp-Gibson, E., Severtsen, B., Vandermause, R, K., and Corbett, C. (2016) Understanding family members experiences of facilitated family presence during resuscitation. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses.

- Chen, C., Tang, J., Lai, M., Hung, C., Hsieh, H., Yang, H., & Chuang, C. (2017) Factors influencing medical staff's intentions to implement family‐witnessed cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A cross‐sectional, multihospital survey. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing; 16(6), pp. 492–501.

- Cormack, D., Gerrish, K., and Lathlean, J. (2015) The Research Process in Nursing. London: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Considine, J., Shaban, R, Z., Fry, M., and Curtis, K. (2017) ‘Evidence-based emergency nursing: designing a research question and searching the literature’. International emergency nursing; 32, pp.78-82.

- Compton, S., Levy, P., Griffin, M., Waselewsky, D., Mango, L, M., and Zalenski, R. (2011) ‘Family-Witnessed Resuscitation: Bereavement Outcomes in an Urban Environment’. Journal of palliative medicine; 14, pp. 715-721.

- Creswell, J, W., Clark, V, P., and Garrett, A, L. (2003) Advanced mixed methods research. Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioural research. Thousand Oaks, Canada: Sage, pp.209-240.

- Cumin, R, O., and Hazinski, M, F. (2000)The Most Important Changes in the International ECC and CPR Guidelines.Journals of the American Heart Association; 102(37), pp. 376.

- Critical Appraisal Skill Programme. (2018) CASP Checklist. [Online] Available at: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/. [Accessed on 4th November 2019].

- Curtis, E, A., De Vries, J., and Sheerin, F, K. (2011) ‘Developing leadership in nursing: exploring core factors’. British Journal of Nursing; 20(5), pp. 306-309.

- Curtis, K., Fry, M., Shaban, R, Z., and Considine, J. (2017) ‘Translating research findings to clinical nursing practice’. Journal of clinical nursing; 26(6), pp. 862–872.

- Daly, J., Willis, K., Small, R., Green, J., Welch, N., Kealy, M., and Hughes, E. (2007) A hierarchy of evidence for assessing qualitative health research. Journal of clinical epidemiology; 60(1), pp.43-49.

- Data Protection Act.(2018)Legislation. [Online] Available at: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2018/12/contents/enacted. (Accessed: 23rd September 2019).

- Department of Health and Social. (2015) NHS Constitution for England. London: Department of Health and Social.

- De Stefano, C., Normand, D., Jabre, P., Azoulay, E., Kentish‐Barnes, N., Lapostolle, F., & Adnet, F. (2016). Family presence during resuscitation: A qualitative analysis from a national multicenter randomized clinical trial. PLoS ONE, 11(6).

- Doleac, J, L. (2019) “Evidence‐Based Policy” Should Reflect A Hierarchy Of Evidence. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management; 38(2), pp.517-519.

- Dougherty, L., and Lister, S. (2015) The Royal Marsden Manual of clinical nursing procedures. 9th edn. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons.

- Drewe, C. (2017) Benefits of, and barriers to, family-witnessed resuscitation in practice. Nursing Standard; 31(49).

- Dunn, H., Quinn, L., Corbridge, S.J., Eldeirawi, K., Kapella, M., and Collins, E, G. (2018) Cluster analysis in nursing research: an introduction, historical perspective, and future directions. Western journal of nursing research, 40(11), pp.1658-1676.

- Dwyer, T., and Friel, D. (2016) ‘Inviting family to be present during cardiopulmonary resuscitation: Impact of education’. Nurse education in practice; 16(1), pp.274-279.

- Emergency Nurses Association. (2012) Clinical Practice Guidelines Synopsis: Family presence during invasive procedures and resuscitation. [Online] Available at: https://www.ena.org/practice-research/research/CPG/Documents/FamilyPresenceSynopsis.pdf. [Accessed on 10th February 2020].

- Fain, J, A. (2017) Reading, understanding, and applying nursing research. FA Davis: Philadelphia.

- Fiori, M., Endacott, R., and Latour, J, M. (2019)‘Exploring patients’ and healthcare professionals’ experiences of patient‐witnessed resuscitation: A qualitative study protocol’. Journal of advanced nursing; 75(1), pp.205-214.

- Gerrish, K., and Lacey, A. (2010) The research process in nursing. 6th edn. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Godin, K., Stapleton, J., Kirkpatrick, S, I., Hanning, R, M., and Leatherdale, S, T. (2015) ‘Applying systematic review search methods to the grey literature: a case study examining guidelines for school-based breakfast programs in Canada’. Systematic reviews; 4(1), p.138.

- Haber, J. (2017)Nursing research-E-book: methods and critical appraisal for evidence-based practice. London: Elsevier Health Sciences.

- Hammarberg, K., Kirkman, M., and De Lacey, S. (2016) ‘Qualitative research methods: when to use them and how to judge them’. Human Reproduction; 31(3), pp. 498–501.

- Heaton, J. (2008) Secondary analysis of qualitative data: An overview. Historical Social Research/HistorischeSozialforschung, pp.33-45.

- Herbert, S. (2013) Perception surveys in fragile and conflict-affected states.Birmingham, UK: GSDRC, University of Birmingham.

- Rose, S. (2018) ‘Supporting relatives who choose to witness resuscitation attempts’. Nursing Times; 114(3), pp. 30-32.

- Royal College of Nursing. (2018) Royal College of Nursing Credentialing for Advanced Level Nursing Practice. London: Royal College of Nursing.

- Royal College of Nursing. (2019a) Research and innovation. London: Royal College of Nursing.

- Royal College of Nursing. (2019b) Staffing Levels. London: Royal College of Nursing.

- Royal College of Nursing. (2020) Leadership Skills. London: Royal College of Nursing.

- Sak-Dankosky, N., Andruszkiewicz, P., Sherwood, P.R. and Kvist, T. (2019) Preferences of patients’ family regarding family-witnessed cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A qualitative perspective of intensive care patients’ family members. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing; 50, pp. 95-102.

Dig deeper into Family Breakdown Is A Matter of Concern with our selection of articles.

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts