The Rhetoric of Sultan Qaboos

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

The Omani nation has undergone profound changes during the past half-century. Sultan Qaboos who was the Sultan of Oman from 1970 until his death in 2020 aimed to ‘restore the past glories’ (1972) of the Sultanate of Oman, by working with the people in ‘unity and co-operation’ (1970). Facing underdevelopment and lack of national and social security Sultan Qaboos bin Said set out to develop a modern Oman that is deeply rooted in tradition and culture. Linda Pappas Funsch (2015) argues that the Sultanate of Oman has pursued political and social modernization while remaining grounded in its traditional roots. The Sultanate’s distinct national self-awareness and deep appreciation of historical tradition have contributed to an enthusiastic and unified society. It is a society that remains resolute in the affirmation of its Arab and Muslim identity as it enters into the modern age, while being culturally diverse and inclusive of other customs. .

Sultan Qaboos acceded to the Sultanate of Oman after overthrowing his father Said bin Taymoor in a bloodless coup. When he came to power, the Sultanate was engaged in violent conflict against communist insurgents in the southern region of Dhofar, and it confronted isolation, a low level of social development and a lack of education (Funsch, 2015). Sultan Qaboos bin Said is the only Arab leader to have documented his annual speeches on Oman’s National Day (18th of November, the Sultan’s birthday) and on other occasions (Funsch, 2015; Kéchichian, 2008). The Sultan’s speeches are a testament to his astute planning and reinforcesspeeches are a collective testament to his astute planning and reinforce the importance of documenting written and spoken communication between him to the people (Kéchichian, 2008:112). The speeches are a permanent record of the Sultan’s philosophy, actions and decisions. They provide an image of the man himself, unifying the nation with conviction and passion, and characteristically embedding the country’s glorious history and traditions into his discourse.

The death of Sultan Qaboos on the 10th of January 2020 left the nation bereft. International news media and world leaders contributed to honouring the late monarch’s diplomatic and political achievements. Ben Hubbard, writing in the New York Times of 10th January 2020, stated that, ‘western diplomats marvelled at the consistency of his foreign policy,’ and drew attention to a passage from the Sultan’s speech in 2007:

‘We work for construction and development at home, and for friendship and peace, justice and harmony, coexistence and understanding, and positive constructive dialogue abroad. That is how we began, that is how we are today, and that, with God’s permission, is how we shall continue to be.’

Historical, cultural and religious perspectives have been employed to study and examine the diplomacy and politics of the Sultan. Majority of the studies have emphasised on the elements of culture and family at Omani society and the influence of such elements to override the economic and political developmental concerns at the country (Barret, 2011). Only a limited number of studies have focused on the implications of utilised languages in the speeches of the Sultan in spite of the significant impact of such speeches on the Omani populace.

a Joseph A. Kéchichian (2008) looks at Qaboos’s speeches, but considers them from the point of view of the different topics which the Sultan addresses – topics such as infrastructure, education and training, agriculture and domestic concerns.

This study, by contrast, focuses on the effects of language and rhetoric which the Sultan deploys in his political speeches. Charteris-Black (2005) notes that the effect of rhetorical strategies is frequently the result of their combination. Therefore, it is of value to examine the interactions of strategies as well as looking strategies individually (Charteris-Black, 2005: 11). For a speaker to successfully convey a message and establish an ideology, he/she and the listener must want the same thing (Jones and Wareing 1999: 34). As a result, to achieve compatibility between audience and speaker, politicians often employ strategies that promote national unity (Ball and Peters, 2000: 81). Consequently, this study first aims to answer the research question:

1.How has the speaker achieved unity and hope through language? With this, I examine the collocates and semantic relations that are associated with the connotations of unit

2. What rhetorical strategies does the Sultan employ to create identity and solidarity with the people? .

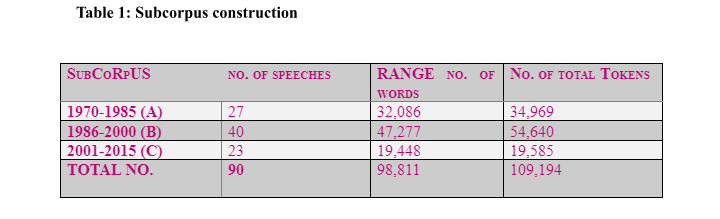

Focusing on 90 of the Sultan’s speeches from 1970-2015, the data consists of a corpus of 109,194 tokens from the official English translation. I observe the transformation of some of the speeches from live recorded footage, which is in Arabic, to the transcription in the original language, and then to the translation into English. The video recordings are mainly from broadcast websites (usually YouTube). The texts vary in length. The focus of the study is the evolution of the speeches and the examination of political rhetoric. However, the range of topics the Sultan covers during 45 years proved to be too diverse to produce effective results from a computational analysis of 90 speeches. As a result, the corpus is separated into three subcorpora, these being: subcorpus A, the beginning of a reformation; subcorpus B, the establishment of united policies; and subcorpus C, an established nation.

In order to carry out an extensive analysis, strengthen arguments and overcome limitations arising from working with a relatively small corpus (Angouri, 2010: 30), the data analysis combines computational and manual methods. The quantitative analysis has used Wordsmith Tools (Scott, 2012) and CFL Lexical Marker (Wools, 2011) in order to identify quantitative patterns of language use in the text. Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) is a theoretical framework in which many have identified as adopting a critical perspective on theoretical concepts such as ideology and power as well as taking into account the relations between discourse and social life (Fairclough, 2013; Baker et al., 2008; Bloor and Bloor, 2007). Whereas Corpus Linguistics (CL) is identified as utilising a variety of different methods to provide insights beyond lexis and grammar in large- scale collections (O’Keeffe and McCarthy, 2010:6). These CL methods are typically quantitative, however to provide further understanding, qualitative analysis is required, such as concordance lines (O’Keeffe and McCarthy, 2010; Baker et al., 2008). CL methods allow the researcher to be objective towards any given text, free from any preconceived ideas regarding the texts linguistic or semantic content (Baker et al., 2008:277). Whereas CDA helps identify social, political and historical ideologies embedded in discursive and linguistic data through social research. Regardless of objectivity, using CL methods on a small corpus, such as the Sultan’s speeches, would not obtain accurate statistics as it would contain small frequencies for results to be reliable. And in order to gain a comprehensive understanding on how language reveals power in social institutions, CDA needs a secondary framework or methodology (Wodak, 2004 cited in Baker et al., 2008:280).

As a result CDA is combined with CL following the argument that each approach can help ‘triangulate the findings of the other’ (Baker et al., 2008: 295). CDA and CL can be used as starting points of corpus analysis of frequencies, clusters and keywords; they identify potential topics of interest. However, frequency-based lexical analysis is not sufficient by itself and would overlook significant themes and topoi. Therefore, applying these two methods with the discourse-historical approach (DHA) helps in identifying implicit strategies based on the language used. Discourse analysis is the particular view of language in use – as an element of social life which is intimately interconnected with other elements. .

Fairclough (2003: 3) has suggested that textual analysis encompasses linguistic analysis as well as ‘interdiscursive analysis’ – as in seeing texts in terms of different discourses, genres and styles. DHA could permit the analyst to disengage from the corpus enough to consult other types of information – in this case, the social and historical environment in which the Sultan addresses his audience (Baker et al., 2008: 295). For the purpose of investigation of the persuasive and reformative rhetoric of this speech, knowledge about the historical, social and concurrent political atmosphere have been integrated to establish the context of Sultan’s discourse.

Chilton (2004) has argued that application of CDA could assist in identification of linguistic aspects which have been utilised within the discourse so as to effectively manage the element of power and exert internal control. There are two distinct features associated with the revelation of power in this context. The first one is the grammatical forms based revelation within any textual discourse and the second one has been the control exerted by any personality on any social occasion. Within the selected social context, the exercising of control by the Sultan through his speeches within the discourses of social events and political environments, would be focused upon. The dominant and prevalent socio-theocratic ideologies such as Islam, national identity and Omani social principles are instilled with the audiences by the Sultan through utilisation of his roles of power.

2.2. A Limitation of the Study

The primary limitation of this study has been the constriction of having to work with a mediated text. Customarily, an Arabic-speaking orator essentially delivers the data. However, the corresponding study has examined speeches through an English translation of a written Modern Classical Arabic (MCA) text. Pascal Damien (2011) identifies MCA as the primary language based medium of literature, education and formal communication.

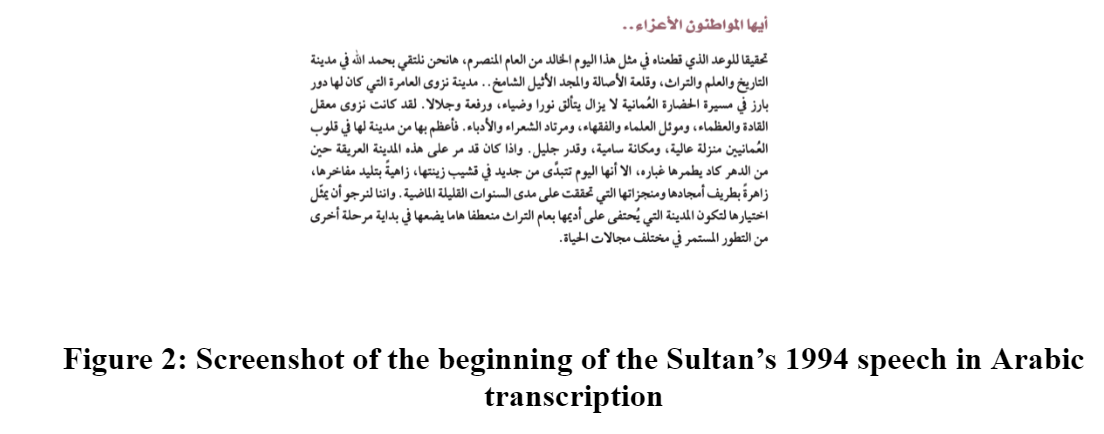

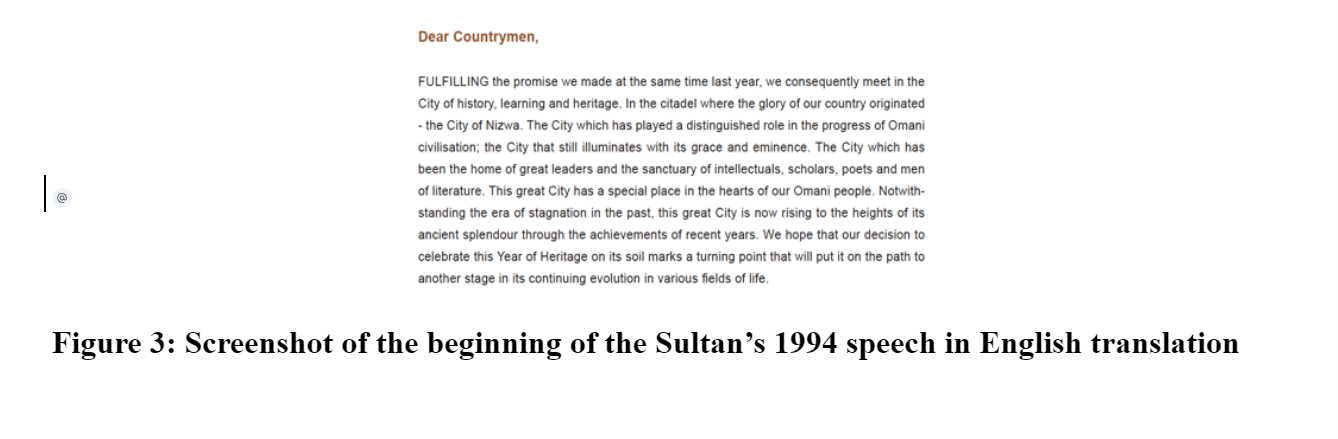

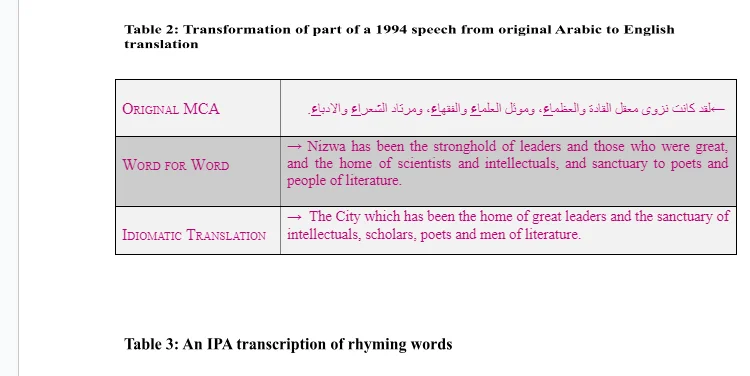

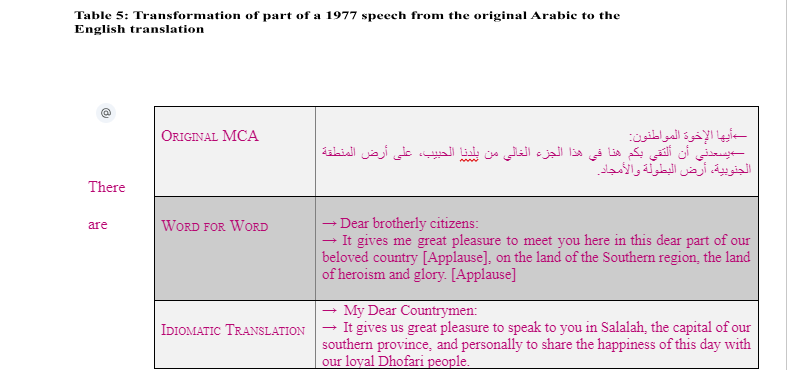

There are some instances where the speaker’s communication is lost through the process of transcription and translation. Various instances could be identified where the thread of communication of the speaker has been interrupted through the application of verbal transcriptions and subsequent translations. The analysis of such research material has been cross-referenced with three different versions of data so as to partially resolve the constrictions of analysing such artefact which has been subjected to double mediation. In order to partially overcome the limitation of analysing a doubly-mediated artefact, I cross-reference my analysis between the three versions of data to further examine the Sultan’s rhetoric. A clear representation on the various ways I could identify problems in the English translation would provide a more accurate analysis of the original Arabic speech. Figures 1, 2, and 3 below illustrate the process of transformation of the Sultan’s speech given on the occasion of the 24th National Day (18th November 1994) in the Governate of Nizwa.

Figure 1: Photo of the Sultan’s speech in the Governate Governorate of Nizwa in 1994

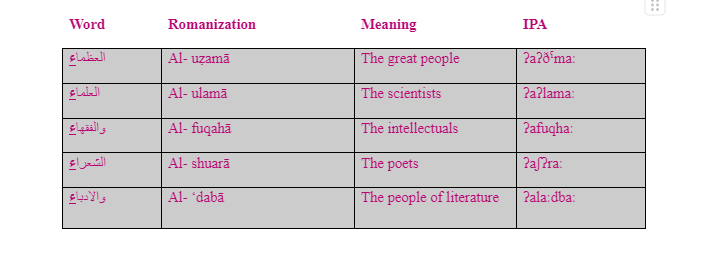

Because Arabic is a phonetic language, it is useful to analyse the speaker’s manner of articulation and delivery of rhythmic words in different settings throughout the corpus. Incorporating Arabic IPA mapping, I analyse the euphonic effect of specific letters and their recitative effects (Brierley et al., 2016; Damien, 2011). The speaker’s articulation and delivery of rhythmic words when addressing different topics increases the audience’s appreciation of, and loyalty to, the speaker. The speaker’s articulation and delivery of rhythmic words, while addressing different topics, increases the audience’s appreciation of, and loyalty to, the speaker. The Sultan uses euphony in his praise for different cities, further enhancing emphasis. The tables below present an example of how language changes through the process of translation, while also illustrating the effects of word choice in a spoken text. .

3. Nationalism

The Sultan maintains throughout his speeches that his primary concern from 1970 has been for the Omani citizen (Funsch, 2015; Kéchichian, 2008). Qaboos repeatedly explains his motives and reminds the people that his original goal was to ‘transform life [for Omanis] into a prosperous one with a bright future’ (1970). The new monarch recognises the importance of the Omani citizens’ rights and obligations, calling upon each individual to ‘take as much as he gives of his efforts, sweat, sincerity and loyalty to his dear land’ (1974). Moreover, he preaches loyalty not to him or to and his crown, but rather but to the country. The Sultan makes clear his intentions towards the Omani ‘sacred’ land and his loyal people who are willing to work towards their ‘country’s glory, honour, progress and prosperity’ (1975). .

In this context, the Sultan employs multiplicity of techniques to engage with hope and aspiration of developing a secured and united Oman. This primarily outlines application of conviction rhetoric by the Sultan to engage with audiences. Charteris-Black (2014: 108) has opined that conviction rhetoric is particularly effective in conveying to the audience the most strong and opinionative convictions and intentions of leadership elements. The emphasis is on choice of words, figures of speech and delivery features including the intensity of expression and volume. Sultan Qaboos aims at suppression of doubts and apprehensions of the audience through such rhetorical devices so as to persuade the populace in favour of presuming a prosperous future. Audience engagement is fostered through presenting views and ambitions by the Sultan. Conviction rhetoric is utilised to deploy pathos and generate an appeal to nationalistic/identity based ethos as well as to the moral purpose of audiences. Emotional intensity in the applied rhetoric and demonstration of passionate commitment are required to foster engagement in religious and ethical beliefs within the audience(Charteris-Black, 2014: 108).

Stevenson (1937) has argued that there are words that do not ‘simply describe a possible fragment of reality’ (Macagno, 2014: 103). Stevenson has claimed that a ‘magnetic effect’ is associated with words such as ‘terrorist’ or ‘freedom’ (Stevenson, cited in Macagno, 2014: 104). Influencing human judgement to realise the potential of triggering particular emotions is the objective of such moral value imbuing words. CL and CDA have been utilised to locate and track words, phrases and sentences in which deterministically nationalistic emotions have been invoked by the Sultan in the audience. As the corpus has been divided into three subcorpora, the changes in language and rhetoric has been examined. The prevalent argument has been that rhetoric of Sultan has changed over the process of Omani national progress despite the consistent theme of nationalism. This outlines that unitive language and syntax could facilitate the invocation of nationalism.

3.1. Use of Unitive Language

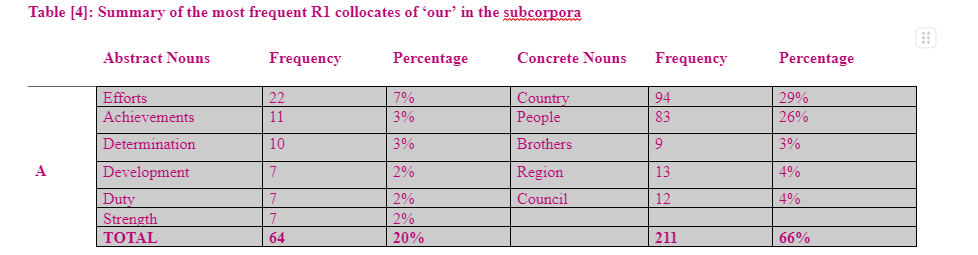

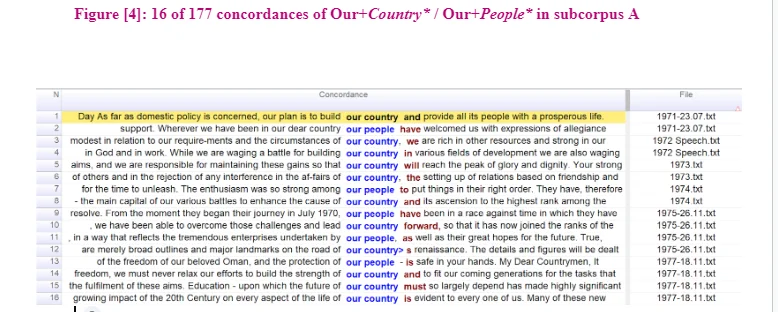

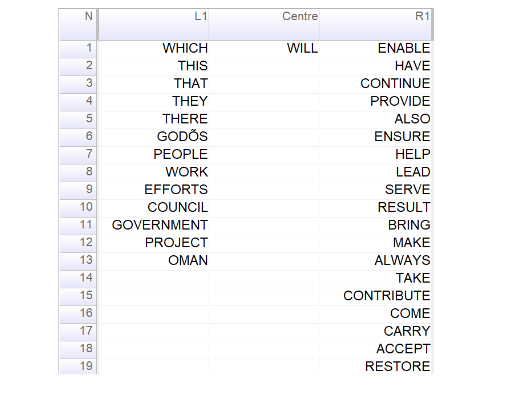

The frequency of the words which had connoted the element of Unity could be determined through a computational corpus analysis of speeches delivered during 90s. The most effective point of initiation of understanding a corpus is frequency word list (Tribble and Jones, 1997 cited in Baron et al., 2009: 41). The word list formulated through Wordsmith displays the words with highest frequencies of occurrence in the corpus. Table [4] shows the frequency of words expressing unity between nation and government. The determiner ‘our’ and inclusive pronoun ‘we’ could be identified to have occurred most frequently in the corpus, indicating the attitude in which the political discourse is categorised by the speaker. Words, such as ‘together’ and ‘us’, outline the determination of the speaker to emphasise on the supposed involvement of the people in the government decisions. Such vocabulary based Corcordance and collocate analysis, involving each of the subcorpus would assist in qualitative analysis of the manner in which addressing the audience is performed by Sultan Qaboos regarding different phases of national growth and progress. Subcorpora data evaluation could outline the persuasive and positive rhetoric through which patriotism is provoked by the Sultan within the audience to strive towards the objective of ‘complete dedication to the service of Oman’ (1977).

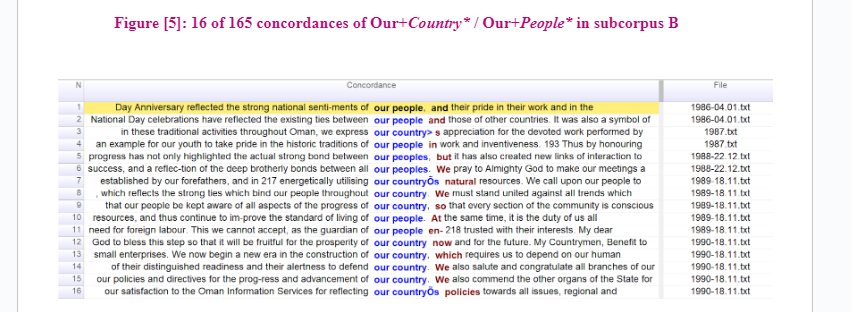

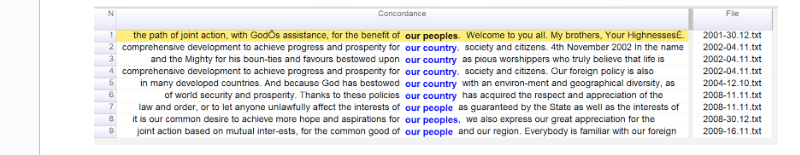

within the audience to strive towards the objective of ‘complete dedication to the service of Oman’ (1977). Exploring the inclusive determiner ‘our’ sheds light on the philosophy the speeches are built around, and which Qaboos seeks to inculcate into his audience: ‘Oman is a country with a deep-rooted history, a distinguished character, which has its own philosophy in social life’ (1993). To determine the context of the determiners with diverging lexical items utilised by the Sultan over the years, the concordance of ‘our’ in each subcorpus would assist. The focus would be on the words driving his rhetoric and the manner in which this change has occurred through the years. Sinclair (2003) argues in favour of interpreting the repeated words in a concordance with similar meaning or word class. R1 collocates of ‘our’ portray the significant themes which the Sultan addresses. Table [4] is consists of a list of the most frequent R1 collocates of ‘our’ depicting key topics occurring throughout the subcorpora. In order to summarize a large number of collocate patterns, I have divided the results into two categories, abstract nouns and concrete nouns. As the three subcorpora differ in length, the table presents the percentage frequency as well as the raw frequency of each example collocatefrequency as well as the raw frequency of each example collocates. It can be seen that concrete nouns are more frequently used in the corpus, indicating a united responsibility of audience and leader with regard to country and people. In subcorpus A, country and people are used the most frequently, at 29% and 26% respectively. While the speaker still uses these specific concrete nouns in subcorpus B, the frequency is significantly lower. In subcorpus C, by contrast, we see a complete change in language, revealing a sense of finality in the Sultan’s speeches.

3.1.1. Concrete Nouns

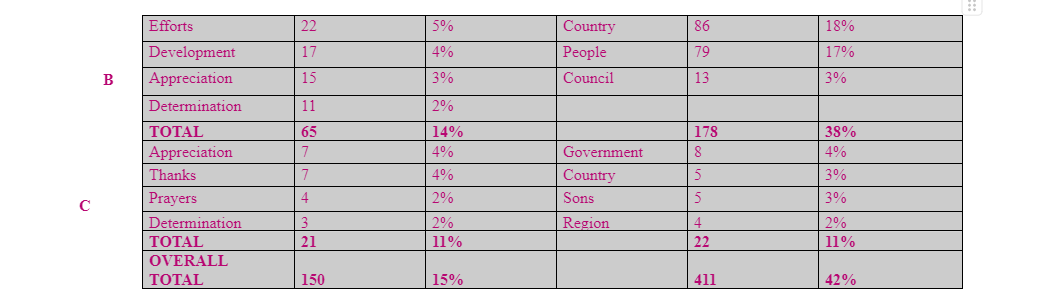

A comparative analysis of the Sultan’s use of concrete nouns helps us to appreciate the reason for the significant changes in frequency percentages over the years. A qualitative analysis of subcorpora A and B indicates the different meanings and contexts in which the phrases ‘our+country’ and ‘our+people’ are used. Figures [4] and [5] are concordances of the search words from subcorpora A and B.

There is a common theme of responsibility and accountability. The following examples portray the various ways in which the speaker evokes nationalism through language emphasising togetherness: ‘our plan is to build our country’ ‘we are waging a battle for building our country’ ‘we are responsible for maintaining these gains’ ‘the future of our country’ ‘we have been able to overcome those challenges and lead our country forward’

Regardless of year, Qaboos focuses on a semantic field of development: build, maintaining, overcome, forward, lead, future, gains. The active voice is prominent in the subcorpus. The speeches indicate an active subject of ‘we’ and ‘our’. The person deixis results in a portrayal of an ongoing participation and relationship between government and people. The speaker places emphasis on not only joint responsibility but also joint work and achievement. The present participle (maintaining, building) strengthens the rhetoric of continuity, thereby encouraging the audience to continue ‘building’. Moreover, the infinitive ‘to build’ acts as a complement, indefinitely linking the subject, ‘our’, to building Oman and helping to ‘provide all its people with a prosperous life’. However, the subject is used differently here; it does not include the audience, but instead focuses responsibility on the Sultan himself. The failure to distinguish between different uses of the same pronoun is a limitation of quantitative corpus analysis. Sultan Qaboos rarely refers to himself as ‘I’; he rather unites himself with the country or with the government. He does not regard himself as an individual anymore. The formation of a united front began when the Sultan took the throne on the 23rd July 1970, identifying himself as ‘I and my new government’. Therefore, a corpus analysis is not able to distinguish between a unitive we (leader and people) and the governmental we (government and leader). For example: ‘We renew to you our pledge to dedicate our life to the service of our dear people and country.’ As this is a promise for a better future, the governmental we is used to address the public. The most prominent ‘us’ and ‘them’ distinction is between Oman and those threatening its development: ‘we had also to grapple with and destroy the menaces of communist terrorism which threatened what we hold dear.’ Pennycook (1994) suggests that if the subject is constructed of different positions, it has different discourses; hence, the pronoun ‘I’ has a complex relationship between discourse and subjectivity. As a result, a focus on the

Sultan’s use of ‘I’ is significant in discovering in which contexts he felt the necessity to drop the role of ‘we’ the government, and display a personal judgment; this is further discussed in the next section. As this phase in his reign (1970-85) focuses on rallying his countrymen to build a country devoid of modern infrastructure and lacking necessary resources such as health and education, Qaboos is attempting to build morale by structuring his prose to evoke optimism and strength. We have established that the Sultan consistently ties progress with the Omani citizen, placing glory not on himself but the people. Forever proud of his fellow citizens, Qaboos deepens his appreciation of the Omani citizen, who ‘possesses the vibrant energy and active spirit that [can] carry him forward to the furthest horizons’ (1994). A consistent expression of approval is rewarding for citizens to hear, and the head of state thereby enhances motivation, instilling pride in accomplishments and faith in their capability. Figure [5] further reflects this rhetoric of inspiration in the Sultan’s language for a ‘new era in the construction of our country’. We see the Sultan reflecting on the ongoing progress, commending hard work and commitment: ‘Our celebration of the 15th National Day Anniversary reflected the strong national sentiments of our people, and their pride in their work’ ‘we express our country’s appreciation’ ‘progress has not only highlighted the actual strong bond between our people’ ‘deep brotherly bonds between all our peoples.’

The concordance examples above emphasise the importance of national unity by the adjective phrase preceding our people. Phrases such as ‘strong national sentiments’ and ‘deep brotherly bonds’ are a result of the progress in developing a united nation. Phrases such as strong national sentiments and deep brotherly bonds are emblematic of the intention to establish a united nation. During the 1986 speech to a State Consultative Council, Sultan Qaboos had reflected on the 15th National Day Anniversary (1985). Leadership elements and figures of prominence from the neighbouring Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states had attended the celebration. The Sultan had signified this occasion concerning placement of the country ‘to its proper place among the nations of the world’ (1986). It is also ‘a symbol of the friendship and co-operation which has helped (to strengthen) our relations with [Arab states] at all levels’. The emphasis had been on the acknowledging the sense of gratitude to the people of Oman through stressing on the development of the national identity of the unified country which enabled the Sultan to achieve military success.

‘The principles of our internal policy are clear and well defined. Its objectives have been manifested during the past three decades, and we are marching ahead with God’s will on the path of comprehensive development to achieve progress and prosperity for our country, society and citizens.’ ‘We currently live in a world of overlapping policies and interests but our international co-operation is in line with the Sultanate’s higher interests and in line with our contribution to the establishment of world security and prosperity. Thanks to these policies our country has acquired the respect and appreciation of the international community.’ ‘Nobody can fail to be aware of the fact that we are all working to achieve further joint action based on mutual interests, for the common good of our people and our region.’ The above demonstrated three examples acknowledge progress achieved during the previous three decades. The Sultan now focuses on perfecting present internal and external policies. ‘We are marching ahead’, expresses the drive to keep pushing for development in the nation. Moreover, the pre-modification of gratitude – ‘thanks to these policies’ – expresses the Sultan’s intention to show the audience the advantages and results of their hard work and the changes that have been made. These results are ‘respect’ and ‘appreciation’ on an international level, reiterating the achievement of his primary goals. Qaboos has consistently emphasised on the suggestive term ‘nobody’ to establish how it is not possible for anybody to not desist from recognising the united effort of the nation. This is emblematic of the achievement of a united country. Subcorpus C outlines the phase where Sultan can finalise foreign policies on the basis of firm, immutable principles of the country as well as the goals of security, peace and happiness for the Humanity in general (2009). .

3.1.2. Abstract Nouns

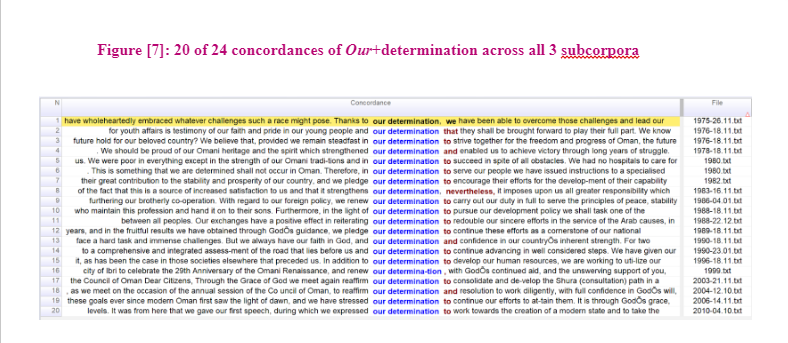

In his first address Qaboos states that Oman ‘in the past was famous and strong’ (1970): his determination is to restore it to its ‘glorious past’ and enable it to take up ‘a respectable place in the world’. His determination never wavered during years of conflict against communist insurgent He calls on his countrymen to ‘bear the burdens with patience and continue our work with steadfastness and determination’ (1971). This drive for resilience and perseverance is reflected in Table [4], where we see the noun ‘determination’ repeated in each subcorpora. Figure [7] shows concordance lines of Our + determination from all three subcorpora. The first concordance line from a 1975 speech shows the search words associated with gratefulness: ‘Thanks to our determination, we have been able to overcome those challenges and lead our country forward, so that it has now joined the ranks of the modern states. We thank and praise God for the success He has granted us.’ The Sultan starts his speech with excitement about addressing the people, for the first time, via the medium of colour television, a milestone which is ‘so precious to [all Omanis]’. The monarch asks his people to look back at ‘what we have been able to achieve, with God’s assistance, for our country and our people’. After five years on the throne, the Sultan takes this opportunity to show communicate to the Omani citizens what they have accomplished thus far. Moreover, during his 5th National Day speech, Sulan had proclaimed success in the

Dhofar War against the Communist Revolutionary movement of Oman. Sultan had also identified the Omani Armed Forces the primary instrument of exerting power of his regime as the purported ‘shield of the nation and the defenders of its sacred soil’. Qaboos has acknowledged the loyalty and efficacy of the armed forces. On the 18th of November 1975 the battlefield successes of the army is celebrated by Qaboos ‘with honour and pride, true heroism and sacrifice’. After eight days of delivering the National Day address, Qaboos appeared before the people of Oman in a televised address to emphasise on gradual national progress through overcoming of challenges. The emphasis on his supposed duty towards the nation and significance of hard word are suggestive of conviction rhetoric utilisation. His linkage with the people is established through pronouns ‘we’, ‘our’ and ‘us’. He aims to ‘renew determination’.

Creating a National Identity 4.1. Omani Morality and Religion

The discourse-historical approach takes into account ‘intertextual and interdiscursive’ relationships between various types of discourses, social variables and institutional frames of context (Baker et al., 2008: 279). Discourse analysis does not only focus on discourse, but also encompasses other related elements (Fairclough, 2010: 5). Fairclough (2003: 2) approaches discourse analysis on the basis of the assumption that language is the core of social life and is therefore fundamental in the research of social analysis. Phillips and Hunt (2017: 646) argue that Sultan Qaboos’s success in developing Oman and as both ‘the genesis and as the guardian of the country’s rapid transition from conflict and poverty to peace and development’ is has been achieved through by providing a ‘Renaissance narrative’ which was sustained by reference to positive changes at the start initiation point of his reign. Phillips and Hunt discuss the instant positive changes in progress which support the Sultan’s ability to reconstruct the nation. into this belief . Successful developments from 1970 are supported by the World Health Organization ranking Oman the first out of 191 countries in ‘healthcare system performance and outcome’ in 1997; moreover, in 2010 the United Nations Development Programme judged Oman to have made ‘fastest progress in human development’ since 1970 (cited in Phillips and Hunt, 2017: 646). As a result, the Omani ‘renaissance narrative’ focuses on national cohesion and the Sultan’s success insuccess of the Sultan in providing welfare and development to the people of the country (Phillips and Hunt, 2017: 647). Within this context, the focus of the investigation would be on instigation of change narratives to appeal to Omani citizens with through tradition and principles with the intention of entrenching a nationalistic Omani identity. Culture and religion are significant contextual factors in the speeches. Al Hajj (1996) contends that unlike the determination of loyalty and identity through nationalism in the West, Muslim countries utilise faith to determine identity (cited in Common, 2011: 218). The Sultan relies on guileful manipulation of general sentiments associated with religion throughout his speeches. His victory in Dhofar, for example, was due to his determinationreflected his in eradicating communism, requirement of ensuring the continuation of the incumbent form of his regime against Communist Revolution in Oman, which, was the biggest threat to the Sultanate, from Oman : ‘we are waging a sacred and armed battle against the enemy of Islam and the country’ (1972) (Kéchichian, 2008: 121). According to Charteris-Black (2004), a political fantasy could be initiated by a leaders through inaugural speeches to formulate a harmonious relationship with the people through

According to Charteris-Black (2004), a political fantasy could be initiated by a leaders through inaugural speeches to formulate a harmonious relationship with the people through sharing of moral convictions and values. Political metaphors are utilised to persuade the audience by leaders towards a supposedly shared vision. Such metaphors related to the audiences and achievement of coveted measures of success in such endeavours is incumbent on ‘linguistic and pragmatic awareness’ of the orator (Charteris-Black, 2004: 47). The conceptual metaphors of politics is conflict and others are utilised by politicians to relate to particular disputes (Charteris-Black, 2004: 91). Both social goals such as freedom and rights and negative social realities, including injustice and poverty could influence conflicts. This section has addressed the research question pertaining to the establishment of security and identity by the Sultan in an authoritarian manner.

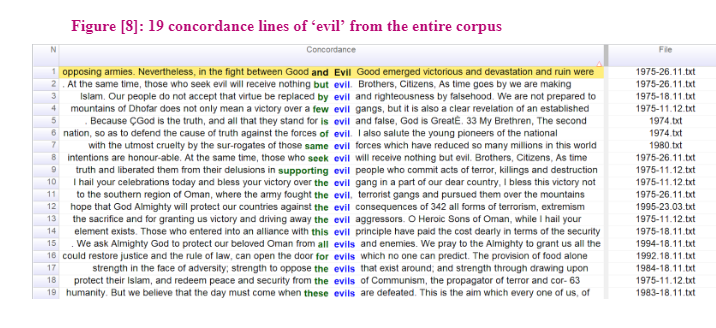

4.2. Conviction Rhetoric

As we have seen above, the fight in Dhofar, and officially integrating the Southern region as ‘an integral part of the Sultanate of Oman’ (1971), is the Sultan’s main concern have been the main concerns for the Sultan in building a national identity. His verbal attacks on communism Communism are examples of anti-outgroup rhetoric counter-revolutionary and counter political-dissent rhetoric with a reactionary purpose, which is otherwise unusual in his speeches. Considerable differences in application of conceptual metaphors by liberals and conservatives could be discerned involving the process of communication of moral perspectives and imperatives. According to Lakoff, the most important metaphor in the conservative moral system is moral strength (Lakoff, 1995). Though it is erroneous to identify the Sultan as a conservative, the incorporation of metaphors in the discourse against Communism has been identified by Lakoff as ‘[c]onservative metaphors for morality’ (Lakoff, 1995: 192). Structuring of speeches of Sultan through metaphorical references to suggestions evil is a force is discernible as well. Conceptualisation of Morality as strength has been intended to strengthen the fight against this purported ‘evil’ through firmness of resolve to resist such evil. Linguistic circumscribing of ingroups and outgroups using corpus methods has been performed through analysis of a KWIC concordance of ‘evil’ to determine lexical features. Figure [8] is a concordance analysis of ‘evil’ from the entire corpus.

The metaphor of moral strength depicts a world in which good is at war with evil forces. The metaphor imposes a ‘strict us-them moral dichotomy’ (Lakoff, 1995: 186). The above examples illustrate this image of good against evil, with good always triumphing: ‘Nevertheless, in the fight between Good and Evil, Good emerged victorious.’ The purported ‘hard and bitter struggle’ experienced by the Omani forces in the years of war against Communists in the South, has been justified by the Sultan as fight against the ‘gangs’ (Marxist revolutionaries). The battle to repress Communist ideals has been depicted as a war of moral beliefs. The reinforcement of the supposed beneficial effects of this victory has been outlined by the Sultan to the people as: ‘ruin was replaced by development projects’. The Sultan places power in the subject ‘Good’ by using the active voice. Moreover, the speaker relies on the conceptual metaphor of doing evil is falling to cast blame while at the same time, use this as a moral lesson: ‘As for those deluded infiltrators from beyond our borders, their voices are bigger than they are. Meanwhile, as we continue to march forward, building with one hand and carrying our weapons in the other, we still hold out our hands to all those whose intentions are honourable. At the same time, those who seek evil will receive nothing but evil.’ The speaker’s use of deixis marks the concept of outgroup. The person deixis, ‘those’, refers to the communist gangs who are against the Sultan and his people. His use of the first-person plural pronoun ‘we’ identifies this as a national fight against the elements belonging to the outgroup structure. The significance of the place deixis ‘from beyond our borders’ emphasizes the common technique of othering: distancing the other from ‘us’, the ‘infiltrators’ have never been part of ‘us’; they are foreign to ‘us’. Also, the post-modification

He ends his speech with a warning. Those who seek the immoral are bound to fall and face the consequences. The outgrouping in this instance is directed towards those who betray Islamic moral teachings. On the other hand, the ingroup, ‘those whose intentions are honourable’, are addressed with the conceptual metaphor morality is strintroced in the form of , ‘their voices are bigger than they are’, reemphasises that their threats have no force in the faength. Those who have the strength to deny evil and are honourable will receive support from the monarch and the country: ‘we still hold out our hands’. With this imagery, Qaboos seeks to attract his audience with the promise of inclusion and connection with the monarch.

4.2.1. Addressing Different Audiences

To deepen the bonds between monarch and people in Oman , Qaboos toured the nation giving speeches in different governates. His speeches delivered in different parts of the Sultanate incorporate praise and personal salutations to the different regions he is addressing. An analysis of the rhetorical effects of the Sultan’s delivery and style in these specific situations allows us to illustrate the effects of the original speech. Charteris-Black (2010) characterises style as being related to word choice, while delivery relates to the control of the voice and other performance-related aspects, such as articulation. I focus on Qaboos’s address to the people of Salalah. In 1977, after the nation’s moral victory against communism, the Sultan celebrated the 7th National Day in Salalah. I analyse his use of language from the original MCA. Table [5] is the transformation of the introductory passage from the original Arabic to my own word for word translation to the idiomatic translation. I have identified the moments when the speech triggered applause from the audience (YouTube, 2015). In the Arabic original, Qaboos’s greeting is explicitly ‘brotherly’: as the Sultan is returning to his birth place (Funsch, 2015; Kéchichian, 2008), he attempts to create a brotherly bond with the people of Dhofar, similar to the brotherly bond of Islam.

reveal. For example, the speaker starts by placing himself as the deictic centre: ‘it gives me great pleasure’. His use of a personal singular pronoun shows the audience the speaker’s personal pleasure in returning to his origins. The pre-modification of ‘Southern region’, ‘dear part of our beloved country’, gives the audience reassurance as well as emphasising the importance of Salalah and its place within Oman, and it therefore elicits applause. ‘The land of heroism and glory’ emphasises the victory Omanis achieved against communism. The Sultan praises the heroism and glory of the region in the Arabic version, whereas the idiomatic translation portrays the Dhofari people as ‘loyal’. It seems that the English translation is written with a view to its reception by a very different audience from the local audience to which the speech was orally delivered, and that to some extent it in effect presents a different speech.

Qaboos’s choice of lexis is in relation to what he addresses next: ‘It is especially appropriate that our first words today should be addressed to our armed forces – to our soldiers, sailors, airmen, and loyal Firqat – close to the battlefields where you fought for the freedom of our people with such noble self-sacrifice and devotion until final victory was won.’ The element of heroism has been emphasised upon by the Sultan to extend commandment to the armed forces. The deictic centre now shifts to soldiers, sailors, airmen and loyal Firqat (militia), with the as the speaker directly addresses ing them. His use of the active voice, ‘you fought’, gives the subject social agency; the material process presents the subject with a powerful role. By this, the Sultan not only displays gratitude, but, he also places the armed forces in a position of power, where they take are accorded with the credit for freeing liberating the people. Qaboos pays tribute to their efforts by emphasising the magnitude (‘such’) of their ‘noble self-sacrifice and devotion’. The variations in addressing the audience outline the intention of the Sultan to convey his message to the people. The comparatively informal speech to the students at the University of Sultan Qaboos in 2000 could be considered a case in point. In this speech, the Sultan addresses Omani youth on various topics from education to history to self-development. This speech encompasses the different roles Qaboos plays towards his people. We see his role as ‘Baba Qaboos’ (Rawat, 2020), an educator, an advisor, as well as his role as monarch, calling for civic duty and patriotism.

When analysing delivery, there are different areas to consider, such as physical appearance, dress, body-language and voice (Charteris-Black, 2014: 31): ‘Rhetorical effects of delivery are achieved by combining features that make an orator sound unique with others that imply a shared set of values. So style is a complex interaction between personal choice and social meaning and between the spoken mode and other means of communication.’ Charteris-Black (2006; 2014) analyses how these semiotic modes are applied to non-Western leaders. Charteris-Black proposes that non-verbal semiotic modes function to create symbolic meaning, enabling a communicable leadership style to arise through an interaction with ‘the conscious and unconscious needs of followers (Charteris-Black, 2006: 24)Charteris-Black, 2006: 24 ). He argues that leaders utilise unique communication styles to differentiate themselves from rivals and to function as signs of leadership performance (Charteris-Black, 2006: 4). Even though the Sultan is not in competition with other leaders, the style and delivery of his speeches are designed with reference to his audience. As Kéchichian (2008: 113) emphasises, the Sultan’s prose ‘was never condescending’, and this is evident in his speech to students of the University of Sultan Qaboos. In this speech, unlike those delivered in more formal settings, the Sultan infuses his speech with ‘symbolic actions’ to emphasise the importance of a particular point (Charteris-Black, 2006: 24). A sense of fatherly affection is evident in this speech, which is not apparent in his other speeches. Notice the differences between figures [9] and [10]. Figure [9] is a screenshot of His Majesty’s speech to the students of Sultan Qaboos University on 2nd May 2000, while figure [10] is a photo taken during a speech which was given in a more formal setting at the third session of the council of Oman. Qaboos’s attire is one noticeable difference, marking a significant difference in his self-presentation in the two different contexts. According to Martinez (2017: 315), most of the Sultan’s formal portraits depict him in the full court dress

of ‘a white dishdasha and embellished bisht with the royal khanjar [ceremonial dagger] at his waist, and the meticulously tied royal turban on his head’ (see figure [10]). This style of headcloth is restricted to the members of the royal family, whereas his clothing at the University is less formal. Martinez (2017) states that contemporary Omani men’s national attire incorporates a simple white dishdasha and a head covering, either a massar or a kumma; however, on more formal occasions, outside the workplace, men may wear a khanjar at the waist (Martinez, 2017: 308). The Sultan’s meticulous choice of dress further signifies the change in setting and terms of address.

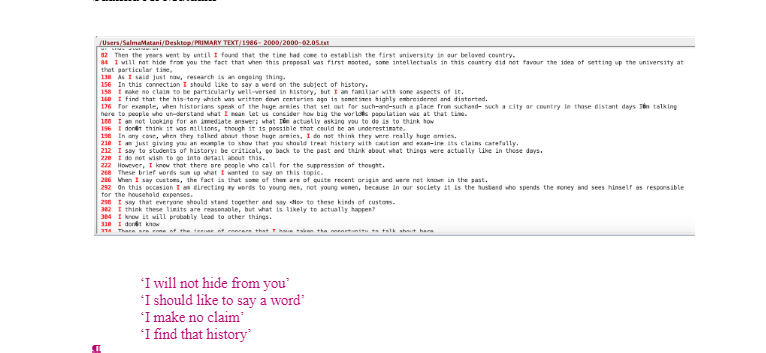

The event is made less formal as the Sultan speaks freely, with no script, which leads to an increase in eye contact and hand gestures, creating a comfortable and personal environment for the students to engage with his speech. The speech starts with the speaker’s commendation to the university and its past students: ‘We are happy to be with you today at this university which was founded a mere fourteen years ago … We are truly proud of what this university has achieved since it was established, and the speeches we have heard and the briefings we have received give us a sense not only of satisfaction but also of immense joy. We are proud of this university, but more than that, we in Oman (and elsewhere) are proud of you.’ As in other speeches, the speaker makes sure to acknowledge achievements and progress. His word choice expresses pride and gratification (happy, truly proud, satisfaction, immense joy, proud); and his use of adjective phrases enhances the sense of accomplishment of the audience, consisting of graduate students. Moreover, an analysis of deixis and deictic centres in this particular speech reveals the Sultan’s determination to connect with his audience. Figure [11] shows instances where the Sultan refers to himself, through the personal pronoun ‘I’. As previously stated, the speaker rarely refers to himself as ‘I’, except is particular circumstances.

Figure [11]: Examples of CFL distribution of the personal pronoun ‘I’ in a speech delivered in 2000

The demonstrated examples outline the incorporation of personal opinion speeches by the speaker. This is an attempt to become inclusive of the young people through demonstrative humanisation of himself by the speaker and through acknowledgement of personal limitations. This specific mode of addressing the people attempts to persuade the audience to become engrossed in the content of communication by the speaker. The Sultan has attempted to provide the clarified measure of reasoning which underscored his decisions so as to gain public trust and he also outlines the challenges he encountered: ‘I will not hide from you the fact that when this proposal was first mooted, some intellectuals in this country did not favour the idea of setting up the university at that particular time … However, we had a different view. We consult, but if we reach a decision we commit ourselves to it. So we ordered that this university should be established.’ (My emphasis.) The above quotation reveals two sides of the Sultan, the trustworthy leader and the firm monarch. Notice the change of pronoun from singular ‘I’ to governmental ‘we’ as he changes roles. By revealing a bit of the process which led to the establishment of the university the Sultan reinforces his power against those who were anti-education. His repetitive use of we+verb signifies action as well as power (italicized in the passage quoted).

4.3. Modality

Modality has been widely studied, notably in the works of Palmer (1986, 2001, 1990), and Coates (1983). Halliday (1994) defines modality as ‘the speaker’s judgment of the probabilities or obligations involved in what he is saying’ (cited in Fairclough, 2003: 164). Convincing imagery and discourses are utilised as standardised features of modalities of political rhetoric by political speakers for the purpose of influencing audiences. Charteris-Black (2014: 108) has referred this as ‘conviction rhetoric’ in which a stringent sense of intention and confidence is conveyed by the speaker through particular choices of words, figures of speech and features of delivery including volume and expressive intensity. The objective of political rhetoric is removal of doubt through presentation of an extensively defined plan for future course of event and, thus, putting out an appeal to the moral sense of purpose of the audience. Furthermore objectives are to engage the audience in beliefs of ethical and religious nature and passionate commitment in the emotionally intense rhetoric of the speaker (Charteris-Black, 2014: 106). The establishment of authority through conviction is performed through modality application. The Omani religious and cultural principles and persistent dedication of the Sultan towards national prosperity and development are reminded by the speaker through conviction rhetoric. The Sultan has also relied upon modality to ingrain the sense of successful development within his people during the establishment period of his government. This observation would be illustrated through the rhetoric which outlines the primary governance based objective of the Sultan, fulfilment of national duty.

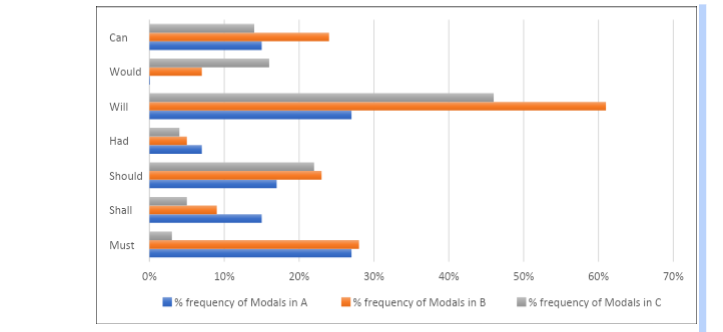

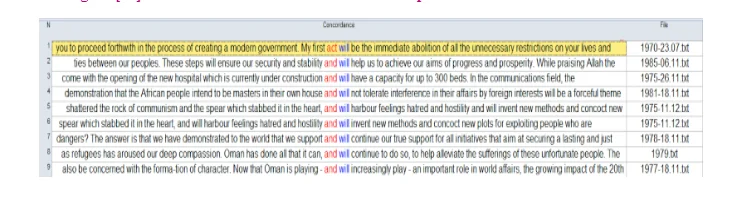

The Sultan’s conviction rhetoric appeals to ethos, and employs pathos and logos. The salience of modality in subcorpora A and B, revealed by the comparison of the three subcorpora in figure [11], highlights the importance of studying the use of modality. The prominence of modality in subcorpora A and B shows that the use of modality is essential in the Sultan’s political speeches. Figure [11]: Frequency of modal auxiliaries in the subcorpora

Figure [12] shows examples in which the speaker expresses intention. The Sultan clearly states, during his first speech in 1970, that his ‘first act will be the immediate abolition of all the unnecessary restrictions’ on the lives of his people. There is a direct exhibition of authority and power in his use of personal deixis ‘my’; especially as this is his first act, the speaker immediately establishes himself in the role of a hero freeing the people from unnecessary restrictions. Adverbial post-modifications, such as ‘immediate’ and ‘unnecessary’, reflect the urgency of starting to undo the actions of his predecessor. Figure [12]: 9 of 202 concordances of Will in subcorpus A

The dire circumstances in which the Sultan has to greet the people are not unbeknown to him. To this effect, the Sultan emphasises on talking about action, development program propositions and living standards improvement plans: ‘these steps will ensure our security and stability and will help us to achieve our aims of progress and prosperity’ ‘As far as domestic policy is concerned, our plan is to build our country and provide all its people with a prosperous life. That will be achieved only when the people share the burden of responsibility and help with the task of building … we shall strive hard to establish just, democratic rule in our country within the framework of our Omani Arab reality, the customs and traditions of our community, and the teachings of Islam – which always light our path.’(1971) Palmer (1990) views epistemic modality as the most distinct form of modality: epistemic modality has the ‘greatest degree of internal regularity and completeness’ (Palmer, 1990: 50). Qaboos uses the epistemic modality of certainty to increase citizen morale and promote motivation towards duty to country Qaboos has utilised Epistemic modality of certainty for the purpose of promoting dutifulness and motivation within the citizen towards their country . The epistemic will ‘refers to what is reasonable to expect’ (Palmer, 1990: 57). In spite of the fact that no exact form for the Epistemic will exists, the above demonstrated quotations are emblematic of the will which further indicates to a reasonable conclusion (Palmer, 1990: 57).

They are examples of the Sultan seeking to connect with his people through reason and logic, logos . The semantic field of confidence in his rhetoric assists him in his attempts to convey that Oman is being guided towards a successful future. This is further illustrated by a concordance pattern list of will from subcorpora A and B. Figure [13] shows that the most frequent R1 collocates of will are verbs. Figure [13]: Examples of concordance patterns of Will in subcorpora A and B

5. Conclusion

The objective of the rhetoric utilised by Sultan Qaboos has been to unify the nation and galvanise support towards a common goal. The preceding study has analysed the multiplicity of rhetorical techniques employed by the Sultan in 90 of his speeches delivered to the people of Oman. It has been evident that unitary rhetoric has been consistently utilised by the Sultan over the years although the change in such rhetoric has been proportionate with the progress made by Oman. The study has outlined that Subcorpus A has focused on semantic expressions of national development as rhetoric of continuity has demonstrated the maintenance of development. Present participle forms of verbs and infinitives which have been followed by unitive ‘we’ and ‘our’ has illustratetd further the supposed objective of national unification and obtainment of better progress. The dearth of ‘I’ as the personal pronoun could illustrate the personal and administrative integration intentions of the Sultan. The focus of the speaker on the achievement of Omani citizens instead on those of his own, is meant to enhance the morale and motivation of his audience. Subcorpus B has focused on commending and praising the people for their toil and on galvanising support from his loyal subjects. The words of endearment exemplify the rhetoric of the speaker to relate to the audience through culture and religion. The sense of esteem is communicated to the audience through adjectival phrases such as ‘brotherly bonds’, ‘sisters’ and ‘sons’. A sense of national identity is fostered through insinuation of religion and prayer. Qaboos has incorporated religious terms to incorporate prayers and praising the divine so that people could relate to such populist rhetoric and find reflection of their thoughts in the rhetoric of the speaker. The achievements in previous three decades are recollectetd in Subcorpus C with emphasis on current outcomes to reinforce gained advantages in the endeavoured projects.

Attempt of formulation of national identity through incorporation of religion in delivered rhetoric has been evident in speeches of Qaboos. His rhetoric on Omani principles and religion outlines the intention to foster a national identity through such constituents. The Dhofar War has been characterised through conceptual metaphorical applications within his rhetorical discourse. Communist rebels have been characterised as an outgroup by Qaboos which marks the utilisation of an unusual rhetorical strategy to structure his presentation of the rebels through metaphors which reinforce the key metaphor of evil is a force. Moral metaphors are utilised by the Sultan to evoke emotions within his audience so as to demonstrate the convincing opposition between evil and good and to foment solidarity amongst his followers against Communism. The rhetoric of religious devotion and prayer are meant to make the audience relate to his purpose. Furthermore, conviction rhetoric has been utilised in various manner to address different elements in terms of addressing the people with pride and praise after gaining victory in Dhofar war. The objective has been to infuse the audience with pride. However, the limitations of a translated text are revealed. The original Arabic transcription provides far better insight into the Sultan’s use of emotive language, specifically constructed for the people of Dhofar, than does the English translation. Another example of specifically constructed address was his speech to the graduates of the university. Here the speaker dresses in a different, less formal way from the way he dresses for other occasions. As we have seen, the address is also less formal; the speaker does not have a script to follow and this allows him to gesture and make eye contact with the audience. On this occasion the speaker sheds his official royal garment and language to advise youth.

Epistemic modality is used specifically to increase the morale of the people and to logically attract Omani citizens towards building a nation. Confidence in a secure and stable country is shown in the speaker’s rhetoric by his use of modal verb ‘will’. Analysis shows that the most frequent pattern is modal verb will+verb, expressing ongoing and future action.

Continue your exploration of The impact of Internet of Things on the Hospitality Industry with our related content.

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts