Addressing Challenges of Ageing

Acknowledgments:

I would like to thank the Almighty God for His unfailing love and unfaltering faithfulness which saw me through. My family for their encouragement – I’m forever grateful.

A special mention goes to Chris McKenna for his support and guidance through out my research.

Copyright and disclaimer:

This project was supervised by a member of academic staff, but is essentially the work of the author. The project is undertaken primarily as a training exercise in the use and application of research techniques. Views expressed are those of the author and are not necessarily those of any other members of the School of Health & Life Sciences.

Due acknowledgement must always be made of the use of any material contained in, or derived from, this project.

Copyright of this major project rests with the author. The ownership of any intellectual property rights which may be described in this major project is vested in Teesside University and may not be made available for use to any third parties without the written permission of the University.

No portion of the work referred to in this project has been submitted in support of an application for another degree or qualification of this or any other university or institute of learning.

ABSTRACT

Introduction: The United Nations and other world governing bodies such as the World Health Organisation (WHO, 2018) report that the world’s population is ageing, suggesting the reason for a rise of elderly people in most countries of the world including the UK. This rise in ageing population presents challenges for health services and society at large as the elderly are susceptible to physical and mental health illnesses as well as functional disability (Fassberg et al., 2016). However, much attention has been towards reducing the physical illnesses for so long instead of pursuing some therapeutic measures. There has been a rise in the awareness of mental health in recent times resulting in notable consideration given to development and implementation of such prevention programmes to promote mental well-being across all population groups. Lifestyle Matters is one of the few occupational-based interventions designed with an aim of sustaining and improving mental well-being in older adults.

Method: The study conducted was mixed-method systematic review to examine the impact of this intervention in fulfilling the aims of sustainability and improvement mentioned earlier within occupational therapy-based practice .

Results: In total, 5 studies met the inclusion criteria: one randomised trial, two qualitative studies and two mixed methods design.

Conclusion: Further research is needed to strengthen the current evidence on the impact of the Lifestyle Matters design in improving mental health in older adults.

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND

Ageing population can be described as a representation of human accumulation of change including physical, psychological and social changes within a certain settlement and this could be claimed as a great triumph but also poses some challenges for the 21st century (Brickner, 2014). In 2018, the World Health Organisation, predicted that the number of older people worldwide was at 125 million and is expected to increase to 434 million by 2050, therefore, making ageing of the global population an important study. The United Nations (2019) and other world population governing bodies such as the World Population Prospects (2019) suggested that one in six people in the world will be aged 65 years or over by 2050 compared to the 2018 statistics. Like most countries around the world, the United Kingdom’s (UK) population is also ageing rapidly. As at 2001, the UK’s census revealed that there were more citizens aged 65 years and older than people under 16 years in the country (GovUK 2018, ). Currently, the UK is ranked 23rd place amongst the countries with the largest elderly population in the world (WorldAtLas, 2021). A major contributing factor to this trend has been the decreased fertility rates, further compounded by the longer life expectancy (Nargund, 2009).

Due to the developments mentioned above, there is need for the invention and implementation of preventative interventions to maintain and enhance the quality of life of the older population (Mason, 1994; Van Malderen, Mets and Gorus, 2013). This will consequently reduce health care costs as currently the ageing population places a strain on the health system, as older people are more prone to developing chronic conditions and multiple morbidities (Divo, Martinez and Mannino, 2014; Buja et al., 2018). Also, ageing involves changes in lifestyle which may affect the mental health of the elderly (Sachs-Ericsson, 2016; Patel., 2020). Studies done both recently and past have shown that older people are particularly vulnerable to factors that lead to depression such as bereavement, physical disability, and loneliness ( Prince, et al., 1997; More). These risks can significantly affect functioning which invariably affects quality of life (Mental Health Foundation, 2020). Thus, supporting individuals to develop and maintain a positive lifestyle for improved mental health, as well as prevent mental illness is the focus for occupational therapists working with geriatric populations within such health practice (Daley, Cristian, and Fitzpatrick, 2006; Atwal, and McIntyre, 2013).

Purpose of the study

The purpose of this study is to examine the effectiveness of the Lifestyle Matters Programme as a community-based intervention to improve and sustain mental well-being in older adults aged 65 years and over.

Objectives and aims

The study aims at examining the impact of the Lifestyle Matters Programme in improving the mental health of elderly patients by summarising the evidence available.

Firstly, this study will identify the barriers and promoters to mental well-being in older people. Then it will collate evidence of the efficacy of Lifestyle Matters intervention in the life context of older people. Lastly, it will make recommendations about the use of the Lifestyle Matters programme for older adults with specific health challenges.

CHAPTER TWO: LITERATURE REVIEW

Studies have shown that amongst the different types of occupational therapy interventions, lifestyle-based intervention to be more effective in improving the mental health of the elderly (Clark et al., 2012; Lund, et al, 2020).

Mental Health in Older People

Over 20% of adults aged 60 years are reported to be affected by a mental or neurological disorder, with the most common disorders in this age group being dementia and depression (WHO, 2017; Bourin, 2018). It has been shown that mental health also impacts on physical health and vice versa (Mental Health Foundation, 2020). Thus, it may be difficult to untangle the interconnections between physical and mental health in the older even when they present the symptoms associated with depression because treating physical conditions is higher on the list than mental illnesses (Cohen et al.,2006)

Researchers such as Tanne, (2004) have found that mental illnesses such as depression impair older people’s lives more than medical illnesses however for various reasons such as the lack of training in many clinicians and health care professionals in recognising mental illness in the older these often go undiagnosed (Lam et al., 2009; Bor, 2015).

Much of the spotlight on mental illnesses in the older population has been directed to Alzheimer’s and other psychological disorders related to dementia which is justifiable given that the prevalence of Alzheimer's is set to triple by 2050 and the treatment and care for dementia patients currently costs the world over $817 billion per year (Dementia Statistics Hub, 2015). However other schools of thought argue that the lack of attention given to the more treatable mental illnesses like depression and anxiety have had the effect on quality of life (Liu, Gou, and Zuo, 2016).

Results from a study by Noel et al., (2004) examining the relationship between depression severity and chronicity other comorbid psychiatric conditions, and coexisting medical illnesses showed that despite the presence of other medical commodities, diagnosis and treatment of depression has the potential to improve functioning and quality of life. It is pivotal that the mental illnesses of the older are acknowledged as they can cause great suffering and lead to impaired functioning in daily life (Bor, 2015).

A report by the Mental Health Foundation (2020), suggests that other than accepting the normal assumption of mental health problems in old age people, adults with related problems are supported. Dening and Barapate in 2004, report that mental ill health can greatly impact people in old age and can significantly affect their use of health and social services.

Relevant policies and guideline

The National Institute for Care Excellence (NICE), suggests that every year in the UK, 1 of 4 adults experiences mental health conditions. Further stating that, mental health conditions (both minor and severe cases) are the largest single disability cause in the UK. NICE works in collaboration with government sponsored groups such as the NHS England and NHS Improvement and Public Health England (PHE) to provide guidance and advice which are evidence-based to help improve social and health care services (NICE, 2015). The NICE guidance on mental health, which serves as the foundation for many commitments in the areas of national strategies, recommends that there should be improved access to psychological therapies as part of a stepped-care model used for treating the common mental health disorders. This guideline further recommends improvement in the physical healthcare and wellbeing of patients with severe mental health disorders. The NICE guidance also advised the allowance for people with these conditions to have controls over choices over their care. Thus, in the case of common mental illnesses, the guideline simply implies monitoring the patient’s progress and outcomes through the least intrusion and most effective interventions, in order to be able to classify the person for higher steps if necessary. In severe cases, NICE guidance focused mainly on long term recovery and aimed at improving the patient's care through early recognition and treatment (NICE, 2015).

Occupational Therapy and mental health interventions for older people

The occupational therapy approach to the mental wellbeing in elderly people is aimed at facilitating the development, recovery, or maintenance of the daily living and working skills (Royal College of Occupational Therapists, 2020). Occupational therapists have the tools and skills to help and empower the older population to manage their physical and mental health and prevent further decline. Occupational therapy practitioners fulfil the profession’s aims by using purposeful activities that are meaningful to the individual to restore function and enable the patient to pursue occupation as a result of therapy (Molke, 2009). Facilitating functionality and wellbeing in the older is imperative to occupational therapy and practitioners accomplish this through the implementation of a holistic approach to client centred care (Whalley Hammell, 2015). The current financial climate in health and social care such as cost to care and access to facilities has required that occupational therapists demonstrate the clinical effectiveness of their interventions in different client groups (Morley and Smyth, 2013). Therefore, the proper implementation of the Lifestyle Matters intervention for required intervention on specified ageing persons may require the expertise of an occupational therapist. As explained earlier, the concept of occupational therapy approach provides checks and balances of health and wellbeing and improvise realistic methods for achieving desired results in specified circumstances which relatively can be applied in case of ageing and mental health. However, due to recent studies in ageing population and its relativity to mental diagnosis, this may invariably imply difficult intervention by the occupational therapy practitioners.

Lifestyle Matters programme

Lifestyle Matters programme is an occupational therapy-based intervention for the older which addresses the quality of life and aims to empower individuals to make positive changes, which promote good physical and emotional health (Britt, Charles, and Valenti, 2008). The behavioural intervention was created from Bandura’s theory of self-efficacy (Bandura, 1977), which propose that, self-efficacy can be developed through four main sources; performance accomplishment, vicarious experience, verbal persuasion and inferences from emotional stimuli which is an indication of self-reliance and or vulnerabilities (Chatters et al, 2017). Although Bandura’s theory of self-efficacy explains the contributing factors to improving the behaviour of the individual, the theory fails to recognise the importance of readiness and motivation of the individual. Other literature (Marcus,Marcus, and Owen, 1992; Lee and Young, 2018) have highlighted the importance of motivational readiness in influencing the decision of behavioural change. Such limitation as that of Bandura's self-efficacy theory limits the effectiveness of the Lifestyle Matters programme as its success requires more than just behavioural change.

Lifestyle Matters intervention draws its roots from the Lifestyle Redesign Manual developed by Clark et al (2011) in the United States. In their research in 2011, Clark and others found out that the programme provided significant long-term health benefits and cost-effective treatment compared to other programmes. The process of acquiring healthy habits and routines in one’s life through the lifestyle redesign program evidently showed that clients made changes for both physical and mental health goals and incorporated meaningful activity on a daily basis to optimise health and happiness (Mountain et al, 2008).

The Lifestyle Matters intervention involves participants taking part in weekly group sessions for over 4 months and monthly one to one sessions and was designed through the application of occupational science theory and research. The content of the intervention includes an exploration of themes such as maintaining and improving mental wellbeing, maintaining physical well-being, safety around the home, dealing with finances, relationships and maintaining friendships (Mountain et al, 2008). Within the programme, ideas for each theme are discussed, including the rationale for the session, possible introductory activities, subjects for discussion and future activities that can be used with the group (Clark et al, 2012).

Gaps and rational of review

Although there is some evidence to suggest the effectiveness of the lifestyle redesign program, the evidence was based on the USA population, therefore, the generalisability of the programme is problematic. Limited research has been carried out to demonstrate the efficacy of the Lifestyle Matters programme. Currently, different literatures suggest that the Lifestyle Matters programme only affects those in need of change or at trigger points, and this requires further investigation.

Furthermore, there is lack of support for the cost-effectiveness of the programme in the UK (Asaria et al., 2014). This research will provide evidence to determine whether the intervention is clinically cost effective in a UK context. The results will discuss and provide decision makers with required implementation decisions. The questions being posed through this research are important given the increasing numbers of older people, pressure on the public purse and the associated need to support good health in the life span plan.

Some literature show promising results, however, more research needs to be conducted on improving self-efficacy and quality of life by helping participants socialise and engage with peers while teaching those new skills. Therefore, the need for reviews to address the various gaps in literature is important and evident. Notably till date, no current systematic review has been carried out to address this research question. Thus, it is on the basis of the gap in research literature that the key objectives of the present study were formulated.

CHAPTER THREE: METHODOLOGY

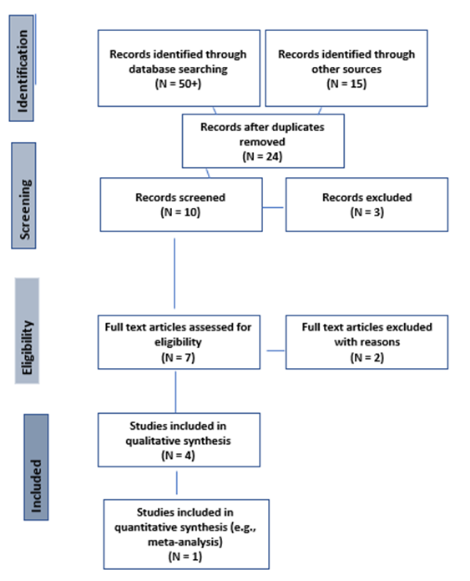

This chapter outlines and discusses the methods for the systematic review and has been designed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) Guidelines (David, Liberati,Tetzlaff and Altman, 2009). The use of a well-developed systematic review process is to eliminate low quality and irrelevant studies (Boland, Cherry and Dickson, 201; Atkins et al., 2014). The process includes accurately formulating the clinical questions to answer which for this research is:

Does Lifestyle Matters intervention improve and maintain the mental well-being of people aged 65 years and over?

The research question was formulated using the evidence-based practice formula, PIO (Population, Intervention and Outcome) framework (Fineout-Overholt and Johnston, 2005; EBSCO, 2019; Melnyk, and Fineout-Overholt, 2019). Table 1 below, describes the population, intervention, and outcome of the present study.

Table 1: PIO table

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

This study reviewed studies which used Lifestyle Matters as an intervention to improve the mental well-being of older adults both qualitative and quantitative methods. This process is a mixed-method systematic approach, and it involved reviewing and combining studies from different research traditions to create a guide in decision making (Pearson, 2015). Studies with a quantitative design such as randomised controlled trial are recommended as a study design for research evaluating the efficacy of healthcare interventions as they provide the highest quality of evidence on the question of a particular intervention’s effectiveness (El Feky et al, 2018) However, one major drawback of this study design is that in most clinical trials is that there is a challenge of retaining participants. The potential effect of this is that study results are undermined, and the result and integrity of the trial is questioned as data may be missing (Miller, Colditz and Mosteller, 1989; Evans, 2010. Gardner et al, 2016). Qualitative research was useful in this review as it provided rich, indepth information regarding the impact of lifestyle matters in improving and sustaining mental health in older adults (Mays, N. and Pope, 2002).

The review considered research on participants aged 65 years and older who took part in the Lifestyle Matters programme. Excluded studied where those with participants with a score of 18 or under on Mini-mental State Examination (MMSE) or with a high level of depression. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are based on that of the Lifestyles Matters programme (Mountain and Craig, 2008).

Only studies which used the Lifestyles Matters programme in comparison to any other clinical treatment intervention to improve health and well-being in the older were used for the review. It was not a requirement for the literature to specify the other intervention programmes components as these varied across studies.

Search Strategy

The following databases were used to complete the literature search; Ageline, Cochrane Library, PubMed, CINAHL, MEDLINE, Embase, CENTRAL and OTDbase. Multiple databases were been selected as it is suggested by previous studies that searching one database is insufficient for a comprehensive systematic review (van Enst et al, 2014; Peters et al., 2015 and Ross‐White and Godfrey, 2017, ). Databases such as MEDLINE and Cochrane Library were used as the Cochrane handbook (2011) recommends their use when identifying literature related to a topic of interest. Furthermore, MEDLINE, Embase and CENTRAL are recommended for identifying reports of randomised trials (Lefebvre, 2008 )

Grey literature was also searched to ensure that upcoming research that may supplement existing knowledge or offer substantial new information to assist in answering the research question was explored (Mering, 2018). Moreover, searching grey literature also helped in avoiding positive results publication bias (Sibbald et al, 2015). It is important that grey literature is searched because it is less likely that negative results of an intervention such as Lifestyle Matters are published in a journal however such results would have been reported in other sources (Adams, Smart, and Huff, 2017).

Due to the varying quality of grey literature, as it is not typically peer reviewed, the literature was carefully evaluated and critically appraised using the AACODS checklist tool (Tyndall, 2010; Haddaway et al, 2015).

The databases were selected as there enabled a search strategy to be built using a combination of medical subject heading (MeSH) terms and keywords (Boland, Cherry and Dickson, 2017). MEDline, Embase and CINAHL were utilised as there are considered the first three most important databases for reports of clinical research (Halladay et al., 2015, Sampson et al., 2016).

The search strategy comprised of three stages:

1. A limited search in Medline and CINAHL to identify the relevant keywords included in the titles, subject descriptors and abstracts.

2. Terms identified from the search were then used for an in-depth search of literature.

3. Bibliographies and reference lists of articles gathered from the second stage were searched.

In principal, the systematic review focused on studies which conducted research on the effectiveness of Lifestyle Matters in sustaining and improving mental health of the older adults. The initial search terms will be ‘Lifestyle Matters’ and ‘mental health’ in all databases. Table 2 below shows further terms which were be used to conduct the search.

Table 1: Key terms and search phrases for review

Study selection

Studies were independently assessed and reported using the PRISMA flow diagram (see Diagram 1). Studies were then reviewed for their validity prior to retrieval of information. The paperswere selected based on their titles and abstracts retrieved checked to ensure they met the inclusion criteria. This stage was ensure the reliability of the conclusions of the systematic review (Shamseer et al., 2015)

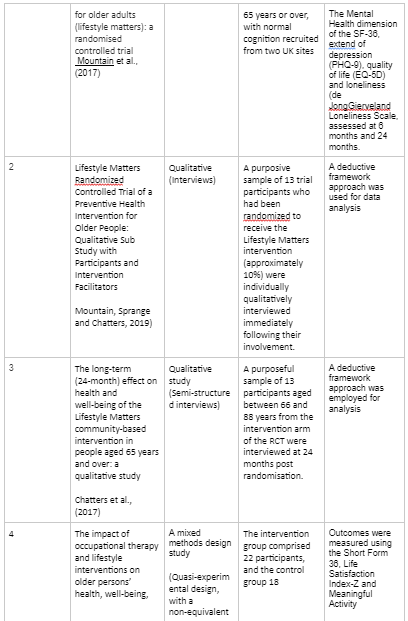

A total of 7 studies were considered appropriate for this review. Two studies were excluded during the eligibility stage of the PRISMA flow diagram leaving 5 studies to be reviewed. From these was 1 randomised controlled, 2 qualitative studies, 2 mixed methods studies.

Diagram 1: PRISMA flow diagram

Quality Assessment

The quality of the studies fulfilling the selection criteria was important for their use in the review. As such, the review assessed the quality of studies using the quality of the PeDro Scale, which is a list of questions based on the Delphi criteria list for quality assessment of systematic reviews (Verhagen et al., 1998). The studies were scored from 0 to 10 on the PeDro scale, the higher score indicating better quality (de Morton, 2009). Data extraction was performed by the author, and this was through identifying sample characteristics, control of intervention and outcome measures.

CHAPTER FOUR: FINDINGS

A randomised controlled study by Mountain et al., (2017) testing whether the occupation-based lifestyle intervention with 288 independently living adults aged 65 years or over, with normal cognition recruited from two UK sites. Results from the research showed that the Mean SF months differed by 2.3 points (9.5 CI: -1.3 to 5.9; P = 0.209) after adjudgements. The researchers reported that the analysis showed limited evidence of the clinical or cost-effectiveness in the recruited population and the analysis of the primary outcome revealed that participants were mentally well at baseline. From this study, Mountain et al., (2017) questioned how preventative interventions as Lifestyle Matters can effectively be targeted to those who may be at risk of mental decline.

A follow up study of the research (Mountain, Sprange and Chatters, 2019) exploring the acceptability, experience, and the short term impact of the preventative intervention by conducting semi-structured interviews with 13 participants immediately following their involvement in the study reflects that behavioural changes were identified within the interview data gathered. Furthermore, the researchers reported that the lack of participants' adherence to the overall intervention affected the overall impact of it. The study supported the quantitative trial results which implied that the researchers had not recruited participants who regarded themselves as being at risk of suffering from mental illness due to their age.

Another study which sought to examine the long-term effects of the Lifestyle Matters programme on lifestyle choices, well-being and participation in meaningful activities. was later conducted for a 24 month period (Chatters et al., 2017). Results showed that the majority of the participants were engaging in new or neglected activities, with all 13 participants reporting to have been experiencing the benefit of attending Lifestyle Matters such as a better perspective on life, interest in trying new hobbies and meeting friends. Several of the participants reported being more adaptive to changing circumstances but the significant and lasting impacts of the programme was in 2 of the 13 participants interviewed. Thus, the majority of the interviewed participants reported minor benefits and increases in self-efficacy, but did not report to have significantly experienced improvement in their health and well being. Participants who had experienced major benefits from the intervention reported to have had life changing events. This implies that the intervention is possibly most effective when lifestyle is reconsidered in order for mental health to be sustained.

The forth study analysed was conducted by Johansson and Bjorklund (2015) utilised a quasi-experimental design, with a non-equivalent control group combined it with semi-structured interviews. Statistical results from the study showed significant enhancement in general health variables such as vitality and mental health, and positive trends for psychological well-being. However, no statistical differences between the intervention group and the control group were noted. Furthermore, a qualitative analysis based on Occupational Adaptation pointed out social factors as a compliment to the overall results.

The last relevant study which used the Lifestyle Matters approach with a group of older people in warden controlled accommodation found out through feedback from data from individuals feedback and achievements that participation in activity had a positive and beneficial effect on the mental wellbeing of participants (Davidson, 2011).

CHAPTER FIVE: DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONS

The bulk work of an occupational therapist is dealing with the ageing people. Occupational therapy practitioners will always play an important and major role in supporting and assisting these ageing populations mentioned above in order to achieve the positive aims of meaningful life and maintaining their independence. However, due to the global increase in ageing population and with more longevity, it is becoming increasingly difficult for the OT to properly carry out their required tasks, therefore, the need for adequate care for these older adults must be ensured for the sustainability and maintenance of their mental well-being (Mason, 1994).

Addressing quality of life through positive interventions can counteract decline in physical and mental health in this neglected population.

The idea of adherence, self-efficacy and motivation are required elements needed in improving the sustainability of the elderly people's well being.

Self-efficacy can be described as individuals believing in their ability to succeed. PeraltaCaption and Hwang in 2011, reported that the person's perceptions towards occupational activities and capabilities was greatly influenced through self-efficacy. Therefore, occupational therapists should support and encourage the older person throughout the required process which invariably will motivate them in believing in their own abilities, thus, improving their self-efficacy. This discussion shows promising results for improving self-efficacy and quality of life by helping participants socialise and engage with peers while teaching them new skills.

The focus of the Lifestyles Matters programme as a potential intervention for improving mental health in the older will hopefully add to the existing literature in a field where evidence-based research is lacking. It is hoped that results from this research will inform policy makers, occupational therapy practitioners as well as other health care professionals of the various variables which interact with mental health outcomes within this population group.

When implementing this intervention, it is paramount that practitioners consider the variables associated with psychological and social identities; of which interact with the intervention outcomes.

Significance of study

A significant example suggesting the importance of more implementation of Lifestyle Matters intervention is the current pandemic of CoronaVirus (COVID-19), where its management and reduction through the restriction of movements may make it difficult for elderly people to participate in normal occupational activities outside their homes. The correcting measures mentioned above are likely to increase the mental illness amongst the ageing population who may already be isolated and occupationally deprived (Rogge, 2020, Banerjee, 2020). However, assuming a proper or adequate intervention has been in place, it will probably help in limiting such negative effects.

Limitations of research

The major limitation of the study was the lack of research. Furthermore, majority of the research available includes the key drivers of the intervention, Mountain and Gail (2008) in the studies. This means there could potential bias in the results presented. Also, as only one randomised control trial has been conducted on the success of the programme, there is a lack of statistical evidence to support the success of the intervention. Furthermore, the review was conducted by one author and this may affect the validity of the findings. Having one other reviewer would have reduced the potential of bias and unintentional error (Whiting, 2016).

Conclusion

The research has examined the effectiveness of Lifestyle Matters in sustaining and improving the mental well-being in people aged 65 years and older. The findings from the systematic review indicate great potential in the application of Lifestyle Matters as a preventative intervention in occupational therapy practice. However, more robust and high quality research is required to support its effectiveness particularly from trials conducted in the UK.

Future Research

Future systematic research should include more randomised controlled studies on the efficacy of the Lifestyle Matters programme for maintenance of mental well being. More general research could investigate the applicability of the occupation-based wellness programme in a range of settings such as in older adults living in long-term care. Although some research with this population has been done in this area by Devine and Usher (2017), further study is required with a larger sample.

APPENDICES

APPENDIX A: Studied reviewed

REFERENCES

Adams, J., Hillier-Brown, F.C., Moore, H.J., Lake, A.A., Araujo-Soares, V., White, M. & Summerbell, C. 2016, "Searching and synthesising 'grey literature' and 'grey information' in public health: critical reflections on three case studies", Systematic reviews, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 164-164.

Adams, R.J., Smart, P. & Huff, A.S. 2017, "Shades of Grey: Guidelines for Working with the Grey Literature in Systematic Reviews for Management and Organizational Studies", International Journal of Management Reviews, vol. 19, no. 4, pp. 432-454.

Al-Yahya, A.H., Raya, Y. & El-Tantawy, A. 2011, "Disability due to mental disorders and its relationship to severity of illness and quality of life", International journal of health sciences, vol. 5, no. 2 Suppl 1, pp. 33-34.

Atkins, P.W.B., Ciarrochi, J., Gaudiano, B.A., Bricker, J.B., Donald, J., Rovner, G., Smout, M., Livheim, F., Lundgren, T. & Hayes, S.C. 2017, "Departing from the essential features of a high quality systematic review of psychotherapy: A response to Öst (2014) and recommendations for improvement", Behaviour research and therapy, vol. 97, pp. 259-272.

Atwal, A. & McIntyre, A. 2013, Occupational Therapy and Older People: Second Edition, .

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191-215.

Blegen, M.A. 2010, "PRISMA", Nursing research, vol. 59, no. 4, pp. 233-233.

Boland, A., Cherry, M.G. & Dickson, R. 2017, Doing a systematic review: a student's guide, Second edn, SAGE, Los Angeles.

Bor, J.S. 2015, "Among the elderly, many mental illnesses go undiagnosed: Few health care providers have the training to address depression, anxiety, and other conditions in their older patients", Health affairs, vol. 34, no. 5, pp. 727-731.

Bramer, W. et al. (2013) 'The comparative recall of Google Scholar versus PubMed in identical searches for biomedical systematic reviews: a review of searches used in systematic reviews', Systematic Reviews, 2(1), pp. 115.

Brickner, P.W. 2014, "GLOBAL AGEING IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY: CHALLENGES, OPPORTUNITIES AND IMPLICATIONS", Care Management Journals, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 62.

Brickner, p.w. (2014) 'Global Ageing in the Twenty-first century: Challenges, opportunities and implications', care management journals, 15(1), pp. 62.

Britt, H., Charles, J. & Valenti, L. 2008, "Lifestyle matters", Australian Family Physician, vol. 37, no. 1-2, pp. 9-9.

Burson, K., Fette, C. & Kannenberg, K. 2017, "Mental Health Promotion, Prevention, and Intervention in Occupational Therapy Practice", The American Journal of Occupational Therapy : Official Publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association, vol. 71, no. Supplement_2, pp. 7112410035p1.

Chatters, R. et al. (2017) 'The long-term (24-month) effect on health and well-being of the Lifestyle Matters community-based intervention in people aged 65 years and over: a qualitative study', BMJ Open, 7(9), pp. e016711.

Chatters, R., Roberts, J., Mountain, G., Cook, S., Windle, G., Craig, C. & Sprange, K. 2017, "The long-term (24-month) effect on health and well-being of the Lifestyle Matters community-based intervention in people aged 65 years and over: a qualitative study", BMJ Open, vol. 7, no. 9, pp. e016711.

Clark, F. et al. (2012) 'Effectiveness of a lifestyle intervention in promoting the well-being of independently living older people: results of the Well Elderly 2 Randomised Controlled Trial', Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 66(9), pp. 782-790.

Clark, F., Jackson, J., Carlson, M., Chou, C., Cherry, B.J., Jordan-Marsh, M., Knight, B.G., Mandel, D., Blanchard, J., Granger, D.A., Wilcox, R.R., Lai, M.Y., White, B., Hay, J., Lam, C., Marterella, A. & Azen, S.P. 2012, "Effectiveness of a lifestyle intervention in promoting the well-being of independently living older people: results of the Well Elderly 2 Randomised Controlled Trial", Journal of epidemiology and community health, vol. 66, no. 9, pp. 782-790.

Colditz, G., Miller, J. and Mosteller, F., 1989. How study design affects outcomes in comparisons of therapy. I: Medical. Statistics in Medicine, 8(4), pp.441-454.

College of Occupational Therapists 2005, "College of Occupational Therapists: Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct", The British Journal of Occupational Therapy, vol. 68, no. 11, pp. 527-532.

Daley, T., Cristian, A. and Fitzpatrick, M., 2006. The Role of Occupational Therapy in the Care of the Older Adult. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine, 22(2), pp.281-290.

de Morton, N.A. 2009, "The PEDro scale is a valid measure of the methodological quality of clinical trials: a demographic study", Australian Journal of Physiotherapy, vol. 55, no. 2, pp. 129-133.

Devine, M. & Usher, R. 2017, "Effectiveness of an occupational therapy wellness programme for older adults living in long-term care", International journal of integrated care, vol. 17, no. 5, pp. 552.

Downs, S.H. & Black, N. 1998, "The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions", Journal of epidemiology and community health, vol. 52, no. 6, pp. 377-384.

El Feky, A. et al. (2018) 'A protocol for a systematic review of non-randomised evaluations of strategies to increase participant retention to randomised controlled trials', Systematic Reviews, 7(1), pp. 30-7.

Evans, S., 2010. Common statistical concerns in clinical trials. Journal of Experimental Stroke & Translational Medicine, 03(01).

Fässberg, M.M., Cheung, G., Canetto, S.S., Erlangsen, A., Lapierre, S., Lindner, R., Draper, B., Gallo, J.J., Wong, C., Wu, J., Duberstein, P. & Wærn, M. 2016, "A systematic review of physical illness, functional disability, and suicidal behaviour among older adults", Aging & Mental Health, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 166-194.

Fayers, P.M. & Machin, D. 2000, Quality of life: assessment, analysis and interpretation, Wiley, Chichester.

Fayers, P.M. and Machin, D. (2000) Quality of life: assessment, analysis and interpretation. Chichester: Wiley.

Fineout-Overholt, E. and Johnston, L. (2005) ‘Teaching EBP: asking searchable, answerable clinical questions’, Worldviews On Evidence-Based Nursing, 2(3), pp. 157-160.

Gardner, H.R. et al. (2016) 'A protocol for a systematic review of non-randomised evaluations of strategies to improve participant recruitment to randomised controlled trials', Systematic Reviews, 5(1), pp. 131.

Haddaway, N.R. et al. (2015) 'The role of google scholar in evidence reviews and its applicability to grey literature searching', Plos One, 10(9), pp. e0138237.

Johansson, A. & Björklund, A. 2016, "The impact of occupational therapy and lifestyle interventions on older persons' health, well-being, and occupational adaptation: A mixed-design study", Scandinavian journal of occupational therapy, vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 207-219.

Jüni, P., Altman, D.G. and Egger, M. (2001; 2008) 'Assessing the Quality of Randomised Controlled Trials', in 'Assessing the Quality of Randomised Controlled Trials' London, UK: BMJ Publishing Group, pp. 87-108.

Lajeunesse, M.J. & Fitzjohn, R. 2016, "Facilitating systematic reviews, data extraction and meta‐analysis with the metagear package for r", Methods in Ecology and Evolution, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 323-330.

Lee, D. & Young, S.J. 2018, "Investigating the effects of behavioral change, social support, and self-efficacy in physical activity in a collectivistic culture: Application of Stages of Motivational Readiness for Change in Korean young adults", Preventive Medicine Reports, vol. 10, pp. 204-209.

Lefebvre, C., Eisinga, A., McDonald, S. & Paul, N. 2008, "Enhancing access to reports of randomized trials published world-wide--the contribution of EMBASE records to the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library", Emerging themes in epidemiology, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 13-13.

Liu, L., Gou, Z. & Zuo, J. 2016, "Social support mediates loneliness and depression in elderly people", Journal of Health Psychology, vol. 21, no. 5, pp. 750-758.

Lund, K., Hultqvist, J., Bejerholm, U., Argentzell, E. & Eklund, M. 2020, "Group leader and participant perceptions of Balancing Everyday Life, a group-based lifestyle intervention for mental health service users", Scandinavian journal of occupational therapy, vol. 27, no. 6, pp. 462-473.

Marcus, B.H., Marcus, B.H. & Owen, N. 1992, "Motivational readiness, self-efficacy and decision-making for exercise", Journal of Applied Social Psychology, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 3-16.

Marx, B.L., Milley, R., Cantor, D.G., Ackerman, D.L. & Hammerschlag, R. 2013, "AcuTrials®: an online database of randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews of acupuncture", BMC complementary and alternative medicine, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 181-181.

Mason, J. (1994). Foreward. In R. Abeles, H. Gift, & M Ory (Eds). Aging and quality of life. New York: Springer Publications.

Mays, N. & Pope, C. 2000, "Qualitative Research in Health Care: Assessing Quality in Qualitative Research", BMJ: British Medical Journal, vol. 320, no. 7226, pp. 50-52.

Melnyk, B.M. and Fineout-Overholt, E. (2019) Evidence-based practice in nursing & healthcare: a guide to best practice. 4 th edn. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer.

Mering, M. 2018, "Defining and Understanding Grey Literature", Serials Review, vol. 44, no. 3, pp. 238-240.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D.G., and the PRISMA Group, PRISMA Group & and the PRISMA Group 2009, "Reprint—Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement", Physical Therapy, vol. 89, no. 9, pp. 873-880.

Mountain, G., Mozley, C., Craig, C. & Ball, L. 2008, "Occupational Therapy Led Health Promotion for Older People: Feasibility of the Lifestyle Matters Programme", The British Journal of Occupational Therapy, vol. 71, no. 10, pp. 406-413.

Nargund, G. 2009, "Declining birth rate in Developed Countries: A radical policy re-think is required", Facts, views & vision in ObGyn, vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 191-193.

Noël, P.H., Williams Jr, J.W., Unützer, J., Worcbel, J., Lee, S., Cornell, J., Katon, W., Harpole, L.H. & Hunkeler, E. 2004, "Depression and comorbid illness in elderly primary care patients: Impact on multiple domains of health status and well-being", Annals of Family Medicine, vol. 2, no. 6, pp. 555-562.

Patel, V. & Prince, M. 2001, "Ageing and mental health in a developing country: who cares? Qualitative studies from Goa, India", Psychological medicine, vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 29-38.

Pearson, A., White, H., Bath-Hextall, F., Salmond, S., Apostolo, J. & Kirkpatrick, P. 2015, "A mixed-methods approach to systematic reviews", International journal of evidence-based healthcare, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 121-131.

Pearson, A., White, H., Bath-Hextall, F., Salmond, S., Apostolo, J. & Kirkpatrick, P. 2015, "A mixed-methods approach to systematic reviews", International journal of evidence-based healthcare, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 121-131.

Peters, M.D.J., Godfrey, C.M., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Parker, D. & Soares, C.B. 2015, "Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews", International journal of evidence-based healthcare, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 141-146.

Prince, M.J., Harwood, R.H., Blizae, R.A., Thomas, A. & Mann, A.H. 1997, "Social support deficits, loneliness and life events as risk factors for depression in old age. The Gospel Oak Project VI", Psychological medicine, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 323-332.

Rogge, M.M. & Gautam, B. 2020, "COVID-19: Epidemiology and clinical practice implications", The Nurse practitioner, vol. 45, no. 12, pp. 26-34.

Ross‐White, A. & Godfrey, C. 2017, "Is there an optimum number needed to retrieve to justify inclusion of a database in a systematic review search?", Health Information & Libraries Journal, vol. 34, no. 3, pp. 217-224.

Sachs-Ericsson, N., Van Orden, K. & Zarit, S. 2016, "Suicide and aging: special issue of Aging & Mental Health", Aging & mental health, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 110-112.

Sampson, M., de Bruijn, B., Urquhart, C. & Shojania, K. 2016, "Complementary approaches to searching MEDLINE may be sufficient for updating systematic reviews", Journal of clinical epidemiology, vol. 78, pp. 108-115.

Shamseer, L., Moher, D., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., Shekelle, P., Stewart, L.A., PRISMA-P Group & the PRISMA-P Group 2015, "Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation", BMJ : British Medical Journal, vol. 349, no. jan02 1, pp. g7647-g7647.

Shea, B.J., Reeves, B.C., Wells, G., Thuku, M., Hamel, C., Moran, J., Moher, D., Tugwell, P., Welch, V., Kristjansson, E. & Henry, D.A. 2017, "AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both", BMJ, vol. 358, pp. j4008.

Sibbald, S.L., MacGregor, J.C.D., Surmacz, M. & Nadine Wathen, C. 2015, "Into the gray: A modified approach to citation analysis to better understand research impact", Journal of the Medical Library Association, vol. 103, no. 1, pp. 49-54.

Sprange, K., Mountain, G.A., Brazier, J., Cook, S.P., Craig, C., Hind, D., Walters, S.J., Windle, G., Woods, R., Keetharuth, A.D., Chater, T. & Horner, K. 2013, "Lifestyle Matters for maintenance of health and wellbeing in people aged 65 years and over: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial", Trials, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 302-302.

Srivarathan, A., Jensen, A. & Kristiansen, M. 2019, "Community-based interventions to enhance healthy aging in disadvantaged areas: perceptions of older adults and health care professionals", BMC HEALTH SERVICES RESEARCH, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 7-9.

Srivarathan, A., Jensen, A. and Kristiansen, M. (2019) 'Community-based interventions to enhance healthy aging in disadvantaged areas: perceptions of older adults and health care professionals', Bmc Health Services Research, 19(1), pp. 7-9.

Sterne, J., Savovic, J., Page, M., Elbers, R., Blencowe, N., Boutron, I., Cates, C., Cheng, H., Corbett, M., Eldridge, S., Emberson, J., Hernan, M., Hopewell, S., Hrobjartsson, A., Junqueira, D., Juni, P., Kirkham, J., Lasserson, T., Li, T., McAleenan, A., Reeves, B., Shepperd, S., Shrier, I., Stewart, L., Tilling, K., White, I., Whiting, P. & Higgins, J. 2019, "RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials", BMJ-BRITISH MEDICAL JOURNAL, vol. 366, pp. l4898.

Sterne, J.A., Hernán, M.A., Reeves, B.C., Savović, J., Berkman, N.D., Viswanathan, M., Henry, D., Altman, D.G., Ansari, M.T., Boutron, I., Carpenter, J.R., Chan, A., Churchill, R., Deeks, J.J., Hróbjartsson, A., Kirkham, J., Jüni, P., Loke, Y.K., Pigott, T.D., Ramsay, C.R., Regidor, D., Rothstein, H.R., Sandhu, L., Santaguida, P.L., Schünemann, H.J., Shea, B., Shrier, I., Tugwell, P., Turner, L., Valentine, J.C., Waddington, H., Waters, E., Wells, G.A., Whiting, P.F. & Higgins, J.P. (2016), "ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions", BMJ, vol. 355, pp. i4919.

Stovold, E., Beecher, D., Foxlee, R. & Noel-Storr, A. 2014, "Study flow diagrams in Cochrane systematic review updates: an adapted PRISMA flow diagram", Systematic reviews, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 54-54.

Tanne, J.H. 2004, "Depression affects elderly people's lives more than physical illnesses", BMJ, vol. 329, no. 7478, pp. 1307-1307.

Van Enst, W.A., Ochodo, E., Scholten, R.J.P.M., Hooft, L. & Leeflang, M.M. (20140, "Investigation of publication bias in meta-analyses of diagnostic test accuracy: a meta-epidemiological study", BMC medical research methodology, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 70-70.

Van Malderen, L., Mets, T. & Gorus, E. 2012; 2013, "Interventions to enhance the Quality of Life of older people in residential long-term care: A systematic review", Ageing Research Reviews, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 141-150.

Verhagen, A.P., de Vet, H.C.W., de Bie, R.A., Kessels, A.G.H., Boers, M., Bouter, L.M. & Knipschild, P.G. 1998, "The Delphi List: A Criteria List for Quality Assessment of Randomized Clinical Trials for Conducting Systematic Reviews Developed by Delphi Consensus", Journal of clinical epidemiology, vol. 51, no. 12, pp. 1235-1241.

Whiting, P., Savović, J., Higgins, J.P.T., Caldwell, D.M., Reeves, B.C., Shea, B., Davies, P., Kleijnen, J., Churchill, R. & ROBIS group 2016, "ROBIS: A new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed", Journal of clinical epidemiology, vol. 69, pp. 225-234.

Continue your journey with our comprehensive guide to A Study to Explore the Barriers and Facilitators.

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts