The Nurture Early for Optimal Nutrition Study (NEON)

Introduction

My PhD research was embedded within the Nurture Early for Optimal Nutrition Study (NEON). This research was funded by the CLAHRC North Thames and aimed to explore the optimal and sub-optimal infant feeding practices in the Bangladeshi population of the London borough of Tower Hamlets (3).

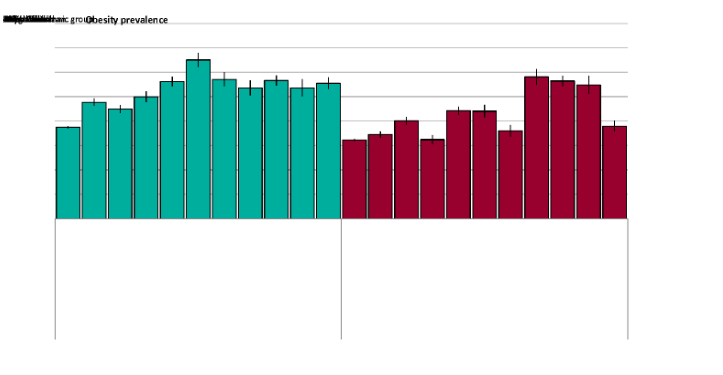

The NEON intervention will explore how to adapt the women’s group PLA cycle for the Bangladeshi population of Tower Hamlets, where the individuals who identify as being of Bangladeshi origin constitute 32% of the population (9). The Bangladeshi population of Tower Hamlets has high rates of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) that relate to over nutrition (10) (see Figure 1: Public Health England Nutrition trends in childhood obesity 2016). These NCDs are also increasing in among the children of Bangladeshi origin (see Figure 1: Public Health England Nutrition trends in childhood obesity 2016) (10). For healthcare dissertation help, accumulating culturally tailored according to interventions becomes crucial in place to address these health disparities efficiently.

The project is divided into five phases (3):

- phase 1 involved four systematic reviews that explored infant feeding practices in Bangladeshi, Indian and Pakistani populations

- phase 2 involved discussing infant feeding practices via focus group discussions (FGDs) with Bangladeshi population of Tower Hamlets and key informant interviews (Imams, heads of nurseries, child health services, child health ambassador, children’s centre care practitioners and Mosque women’s events managers);

- phase 3 –involved interviews about infant feeding practices in Tower Hamlets with community children’s nurse, general practitioners (GPs), health visitors, pharmacists, midwives and public health professionals;

- phase 3 –involved interviews about infant feeding practices in Tower Hamlets with community children’s nurse, general practitioners (GPs), health visitors, pharmacists, midwives and public health professionals;

- phase 5 is to explore adaptations to the women’s group PLA Cycle for the Bangladeshi population of Tower Hamlets

This PhD research was carried out concurrently with phases 2-4 of the NEON study. The recommendations from this PhD research will be addressed in phase 5 of the NEON study.

Participatory models (like the women’s group PLA cycle) involve their target population in the design or delivery of health interventions to ensure that, they are contextually relevant (11). Collaboration, mutual education and acting on the results devolved from the research are the key features of participatory models (12). Mutually respectful partnerships between researcher and the population of interest are important in participatory models (12). Other participatory models have already shown that, they can successfully engage the Bangladeshi population of Tower Hamlets in research design (13). Beck et al., (2005) aimed to develop recommendations for the users and commissioners of sexual health services for the Bangladeshi population in Tower Hamlets (13). They used utilised community participation techniques to explore the cultural and contextual taboos around the access to services (13). They assembledaassembled a steering group optimise optimising community interests within the project. They demonstrated that, community ownership was optimised by using an iterative approach to data collection which allowed the project to address key issues around the access to sexual health services by the target population (14), but they did consider how this iterative process could feed into further adaptation, so that the services remained accessible.

Introduction

The value of reverse innovation is emphasised in both global health and local community engagement. The benefits of this bidirectional learning partnership have the potential to overcome some of the resource constraints faced by health providers, planners and health systems. Interventions developed in LICs could offer a new and cost-effective approach to current models of care in HICs. To optimise the effectiveness of these interventions, an adaptionadoption process should be taken place thatplace, which is standardised through the intervention lifecycle (from conception to implementation). This research will explore the concept of reverse innovation in the context of health intervention adaptation. The intervention, that will be adaptedwhich will be adapted, is the evidence-based women’s group PLA cycle model (15-21).

The value of reverse innovation is emphasised in both global health and local community engagement. The benefits of this bidirectional learning partnership have the potential to overcome some of the resource constraints faced by health providers, planners and health systems. Interventions developed in LICs could offer a new and cost-effective approach to current models of care in HICs. To optimise the effectiveness of these interventions, an adaptionadoption process should be taken place thatplace, which is standardised through the intervention lifecycle (from conception to implementation). This research will explore the concept of reverse innovation in the context of health intervention adaptation. The intervention, that will be adaptedwhich will be adapted, is the evidence-based women’s group PLA cycle model (15-21).

New approaches are needed to tackle resource constraints and changing disease patterns

Modern global health challenges are complex, multi-faceted and consume large amounts of resources (23). They require an interdisciplinary approach, which that considers the whole systems rather than individual problems (23). Worldwide increasing demands for health and healthcare are transforming the way that health system designers maintain existing services and develop new programmes (24). Consumers of healthcare are petitioning for better quality, evidence-based, affordable and accessible care (25, 26). Global health advisors like the WHO and the UN are encouraging the countries to provide universal health coverage by strengthening current services, re-structuring health governance, improving accountability and legislation, and regulating health services from the private and public sector (26-28). These demands are provide increasing pressure on healthcare providers to look further afield for solutions.

Global disease patterns are in transition from high rates of communicable disease to higher rates of non-communicable diseases and this is presenting a contemporary challenge to health systems (29). The growing burden of non-communicable disease includes cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, obesity, type 2 diabetes and some cancers (30). Nutrition is engaged in a battle against two extremes: under-nutrition affects those that are deficient in calories, and over nutrition occurs when an individual is consuming too many calories leading to obesity (31). Both are classified as malnutrition. Malnutrition is an imbalance in the nutrients, that which are being consumed and that are being utilised by the body (31). All the countries are experiencing a growing epidemic of non-communicable diseases linked to malnutrition (32), and changing economic landscapes and demographic variations mean that, the demand for services is transforming the way health providers address these diseases.

In 2015 the WHO stated that worldwide 39% of over 18 year olds were overweight (33). Between 1980 and 2014, the prevalence of obesity has more than doubled, with 15% of women and 11% of men being diagnosed as obese (33). Obesity is a risk factor for type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease, and often has co-morbidities such as micronutrient deficiencies and dental caries (34). Additionally, individuals suffering from these nutrition-related illnesses are getting younger, with 41 million children under five being diagnosed as overweight or obese in 2014 (33). These changes in disease patterns have prompted healthcare providers to adapt to meet new demands on services (2) and look for new models to fill gaps in existing medical professional-led health promotion interventions. Ethnic minority groups in HICs are at higher risk of developing these morbidities than their Caucasian European counterparts, therefore, they are a population of interest for health commissioners (35, 36). Crisp (2015) highlights that, HIC’s health systems have the ability to treat nutrition-related ill-health, but they are generally not good at managing chronic illness and have not developed sufficient preventative mechanisms (37).

In global policy, universal health coverage (UHC) is part of the Sustainable Development Goal 3 Health (part 8). UHC is currently driving the global health agenda: as of 2018, the United Nations (UN) have dedicated an official UN UHC day (12th December) and UHC is achieved, when each member of the population can access all the domains of healthcare (health promotion, preventative, curative, rehabilitative and palliative services) of sufficient quality to be effective, while preventing the risk of financial hardship to the procurer of the service (38). To In order to provide equal access to services the NHS should consider new approaches and/or adapt current approaches to address inequalities in health. With the landscape of health rapidly transforming, however, it is becoming increasingly difficult to provide accessible services to the whole population

Reducing health inequalities is a declared national priority in many economically developed countries (1). The resources needed to address such inequalities in health requiresresources needed to address such inequalities in health require adequate finance, structure, and collaboration between many health system actors. Over the next five years the NHS will continue to move care into the community care by strengthening primary health care services and supporting allied-health professionals and communities to lead on preventive interventions (39). This is in response to an interest in social prescribing and working with social assets and the third sector (39). To In order to optimise the relevance of preventative approaches that are closer to home, we must consider alternatives to the current health professional-led interventions. Community-based interventions have proven a viable alternative in low-income settings,settings; however, the process of implementing such interventions within a trusted universal healthcare system is unchartered. Understanding the future challenges faced by current services helps unravel the contextual influences on health behaviours, barriers to accessing healthcare and limitations of health care providers, that which could affect implementation in the UK.

Clinicians and nurses are equipped with skills that allow them to practice medicine universally. The Brain Drain effect is an economic theory whereby professionals who possess heterogeneous skills move from one country to another for higher social or economic capital (40, 41). This can either be beneficial or detrimental to an economy depending on the migration patterns of the professionals (40). In health and healthcare, health workers traditionally moved from LICs to HICs, presenting a problem for LICs who were financing the training of these health workers and then losing them to health systems that could offer stronger financial gains (42). Now, with changes to the NHS working policies for junior doctors and the impending Brexit restrictions to European mobility, the migration of health professionals is going to be compromised, with more professionals opting to leave the UK NHS (43, 44).

It is apparent that, the UK will face challenges relating to the provision of healthcare. Crisp et al., (2014) stated – “health and healthcare are no longer the sole preserve of traditional professionals and health systems” (45). In LICs the shortages of trained medical staff are prompting not-for-profit organisations and partnerships to explore creative means by using existing pools of knowledge and community resources to address these gaps in services (46-51). The majority of the literature in this area has focused on health worker shortages in LICs, especially in sub-Saharan Africa (52, 53). In the UK NHS, there are severe shortages of health professionals, particularly in primary care (54). The Nuffield Trust report (2014) emphasised that, there are not enough general practitioners (GPs) being trained, more trainees now work part-time, and the existing pool of GPs is under-resourced (54). This problem is not unique to the GPs or the NHS; other HICs are experiencing staffing shortages, particularly in rural areas as health services become centralised (55-58)

Health inequalities in ethnic minority groups

In the UK, demands for NHS services are increasing and there is growing awareness of longstanding unmet health needs such as health equity for ethnic minority groups (39). Furthermore, NHS planners are looking forward to redesign healthcare so that that the people can get optimal healthcare that is tailored to their needs when they need it (39). Ethnic minority groups in the UK experience disproportionate levels of nutrition-related ill-health as compared to their White European-origin counterparts. Differences in the rates of these morbidities have been reported by the majority of HICs (36). In terms of nutrition-related ill-health such as obesity or cardiovascular disease, the main preventable risk factors are amenable behaviours including physical inactivity and poor dietary choices. Addressing these behaviours therefore represents the focus of most preventative interventions.

The rates of ill-health related to nutrition vary globally based on environmental factors and, theoretically, on genetic ones (59). Migratory populations can be at a higher risk of developing their morbidities due to new environments, genetic predispositions and lack of engagement with health systems (59). Failure to engage these populations in health services poses a risk of inter-generational acquisition of behaviours, that which contribute to nutrition-related ill-health (36). This could subsequently create complex disease patterns within the countries of migration (36). Addressing inequalities in ethnic minorities could help countries adjusting to new patterns of disease (59)

There is no specific nomenclature to describe what traits constitute an ethnic minority group in the literature. Villarroel (2018) highlighted the differences in the conceptualisation of ethnicity across Europe and consider this to be a barrier to identifying ethnic inequalities in health (60). Kulatai et al., (2016) suggested that, the constructs of ethnicity are interchangeable based on an individual’s personal relationship with their environment and their heritage (61). Both facets can be influenced by culture (61). Challenges in the terminology lie in inequality and racism, so encapsulating the population of interest without including any negative connotations or terminology, which is challenging. Demographic information regarding ethnicity will vary between countries (60).

Country-level policies that group individuals by ethnicity could further contribute how ethnicity or race is conceptualised within a context. In the UK, Bhopal (2009) considers the White population as the ‘majority’ and then differentiates between minority populations based on their country of origin, e.g. Bangladeshi (36), which is challenging because, White is a category of race, not necessarily ethnicity. Ethnicity and race can often be used interchangeably, which can further complicate how ethnicity documented, leading to misconceptions about social norms and values, that which could influence health service design.

Sproston and Mindell (2006) describes described the ‘general population’ as the whole population of England, regardless of minority ethnic group, which fails to distinguish the seven minority ethnic groups on whom the report focuses (62). Fixating on some of the larger ethnic minority populations and collating the smaller minorities into a single group- Other (61), may further exacerbate issues relating to designing health services that are tailored to the needs of individuals. The terms ‘Other’ suggests that, the policymakers recognise larger ethnic groups, but not smaller groups, and there is not always an option for mixed race/ ethnic groups. Without nuances related to ethnicity, it may be challenging to design appropriate policy and health services to cater to the needs of a population, that which is changing and the disease patterns which that are also changing as a result.

Individual ideologies relating to ethnicity could also influence how it is embodied within the population. Bhopal (2009) agrees agreed that, ethnic group, country of birth and name are proxy indicators of ethnicity (63), but this may only be relevant to first generation migrants as second or third generation migrants may begin to identify with their environment. This suggests that ethnicity could be fluid and open to interpretation by the individual or the community in which the individual resides. This raises questions about which traits should be accounted for during adaptation and how they should be stratified. For the purpose of this PhD, an individual, who belongs to an ethnic minorityminority, is considered to be someone, who does not identify with the majority population in the UK.

PhD Research Aims & Objectives

My approach to this research was built on the assumption that, an efficacious evidence-based intervention which has proven successful in reducing neonatal mortality across multiple cluster-RCTs (2) could undergo theoretical adaptation to produce a set of recommendations which that would allow it to address health disparities in an ethnic minority group in a HIC. Understanding the facets of translating an evidence-based intervention between two contexts required me to explore three areas in my systematically searched literature review. The term translation will refer to the action of moving an intervention between two contexts. The term adaptation will be applied to the act of adjusting the intervention so that it can be implemented within the context and it is also appropriate to the new target population. These terms will not be used interchangeably.

The following section outlines how I addressed this process. I will present the aims and objectives of this research and how each chapter will address each objective in the following section

Aim

To determine how to theoretically translate the women’s group PLA cycle from multiple LICs to the UK NHS context, using the exemplar of infant nutrition in the Bangladeshi population of Tower Hamlets, London.

Outline of chapters in relation to the objectives of this PhD research

The following section will describe how and why I chose the areas of exploration for each chapter. This will begin with the narrative reviews, then the qualitative studies, and the synthesis of all primary and secondary data within Chapter 9: Discussion. Objectives 1-4 will be addressed in the narrative literature reviews of chapters 2-4. In these chapters I searched the literature using the criteria from the Identification, Screening and Eligibility phases of the PRIMSA flow diagram. (REFERENCE).I then critically reviewed and interpreted the literature of the three areas: reverse innovation (Chapter 2); health intervention adaptation (Chapter 3); and the women’s group PLA cycle intervention (Chapter 4). The rationale for the selection of these topics and how they address each objective is explained in the following section.

Chapter 2: Reverse Innovation related to objective 1 (appraise appraising the term reverse innovation, examine current examples from the literature and the conceptual challenges). The concept of reverse innovation was selected because it represents a collection of ideas, which that highlight the challenges related to the inter-country translation of interventions, specifically between LICs and HICs. I decided to conduct a narrative review on the current evidence surrounding the concept of reverse innovation to determine the origins of the term, existing evidence and to help me understand the complexities of the process. I also wanted to consider the challenges to the process, that which goes beyond the initial assumption that it is only about moving intervention from LIC to HIC contexts. I thought, it might help me to pre-empt and address some potential cognitive biases from health providers, participants and health systems. I hoped to include these nuances in my recommendations for adaptation.

Chapter 3: Health Intervention Adaptation related to objective 2 (determine determining the theoretical frameworks that support adaptation of health interventions.). I explored the literature that supports health intervention adaptation to assess the current theories surrounding including adaptation theory and to validate my own assumption, that adapting a reverse innovation for context could facilitate its acceptability and feasibility in the new setting. I also believe that, context can influence culture, and I wanted to determine if there were any models, that which considered the context and culture, particularly for ethic minority groups. I also wanted to explore how an intervention can be adapted to fit a new context without compromising previously successful intervention outcomes.

Chapter 3: Health Intervention Adaptation related to objective 2 (determine determining the theoretical frameworks that support adaptation of health interventions.). I explored the literature that supports health intervention adaptation to assess the current theories surrounding including adaptation theory and to validate my own assumption, that adapting a reverse innovation for context could facilitate its acceptability and feasibility in the new setting. I also believe that, context can influence culture, and I wanted to determine if there were any models, that which considered the context and culture, particularly for ethic minority groups. I also wanted to explore how an intervention can be adapted to fit a new context without compromising previously successful intervention outcomes.

Chapter 3: Health Intervention Adaptation related to objective 2 (determine determining the theoretical frameworks that support adaptation of health interventions.). I explored the literature that supports health intervention adaptation to assess the current theories surrounding including adaptation theory and to validate my own assumption, that adapting a reverse innovation for context could facilitate its acceptability and feasibility in the new setting. I also believe that, context can influence culture, and I wanted to determine if there were any models, that which considered the context and culture, particularly for ethic minority groups. I also wanted to explore how an intervention can be adapted to fit a new context without compromising previously successful intervention outcomes.

Chapter 6: Study 1 will record the results of the key informant interviews. All of the major themes, that which emerged from the data, will be presented in this chapter. These results will be synthesised into a generic framework for the adaptation of the women’s group PLA cycle, which will be usedtoused to inform the topic guide for the FGDs in Study 2.

Chapter 7: Study 2: Focus group discussions with the Bangladeshi population of Tower Hamlets wasFocus group discussions with the Bangladeshi population of Tower Hamlets were related to objective 5 (determine determining how the intervention could be adapted to be acceptable and feasible within the UK NHS context and the Bangladeshi population of Tower Hamlets). Assisted by the community facilitator from the NEON study, I conducted FGDs with members of the population of Tower Hamlets that identified as being of Bangladeshi origin. This helped me to explore the contextually and culturally appropriate adaptation that need to be applied to the women’s group PLA cycle. I then synthesised the results of the three FGDs (2x female participants and 1x male participants) to produce a list of theoretical adaptations to the model to for make making it appropriate and feasible within this specific context.

Chapter 7: Study 2: Focus group discussions with the Bangladeshi population of Tower Hamlets wasFocus group discussions with the Bangladeshi population of Tower Hamlets were related to objective 5 (determine determining how the intervention could be adapted to be acceptable and feasible within the UK NHS context and the Bangladeshi population of Tower Hamlets). Assisted by the community facilitator from the NEON study, I conducted FGDs with members of the population of Tower Hamlets that identified as being of Bangladeshi origin. This helped me to explore the contextually and culturally appropriate adaptation that need to be applied to the women’s group PLA cycle. I then synthesised the results of the three FGDs (2x female participants and 1x male participants) to produce a list of theoretical adaptations to the model to for make making it appropriate and feasible within this specific context.

Chapter 9: Discussion related to objective 6 (create creating a formulaic framework that details the theoretical adaptation process). This chapter of my PhD thesis allowed me to synthesise the concepts from chapters 2-4 and the qualitativestudiesqualitative studies 1 and 2 to createacreate a theoretical adaptation framework for the women’s group PLA cycle intervention. I appreciate that, these adaptations are theoretical in nature, and therefore highlight that, the feasibility and acceptability of the adaptations will be reviewed in the NEON study team meeting and via the NEON study pre-pilot.

The following chapter will dive explore into the concept of reverse innovation in a bid to understand how and why this concept is important to public health during a time, a where resources are ever constrained and the challenges in health provision are increasing. With challenges such as global warming and changing disease patterns, it is potentially time to challenge, where innovation emerges and how it is shared around the globe.

Continue your journey with our comprehensive guide to The Influence of Macro-Sociological Factors on Dementia Patients.

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts