Emergence of Learning through Distance Education during COVID

Chapter One: Introduction

The emergence and rapid spread of the Covid-19 throughout the world has resulted in a global crisis of an unprecedented scale. The Chinese Government announced on December 8th, 2019 that its healthcare services were treating multiple people of an infection that it had since identified as the corona virus disease 2019 (Covid-19) (Bakar and Rosbi, 2020). Covid-19 is a respiratory disease that is highly transmissible from one person to the next- the virus is spread through physical contact with infected individuals, whether they exhibit the signs and symptoms of the disease or not (are asymptomatic). The most common signs and symptoms that exhibited by infected individuals are fever, cough, difficulty in breathing and sore throat (World Health Organization (WHO), 2020). The rapid spread of the virus and its development into a pandemic was promoted by various factors, such as: the fast and efficient transmission of the virus; the transmission of the virus through air (Yang, Zhang and Chen, 2020); constant human proximity and physical contact between the infected (symptomatic or asymptomatic) and the non-infected people; various populations’ vulnerability to the disease, for example those aged 65 years or more, as well as individuals with low immunity and those with pre-existing health conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, etc.; and the ease of movement due to technological advancements that have made it easy for people to travel from one part of the world to the other (Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2020). Following its rapid spread, WHO (2020), in January 2020, declared it a public health emergency worthy of international concern, and later on in March 2020 a pandemic after it was reported in several continents. Besides the numerous social and economic impacts it has resulted in, the Covid-19 pandemic has also brought about severe health impacts, which have continued to place increasing pressure on the world’s healthcare system as countries struggle to curb its effects and save their citizens’ lives. Among the most notable health challenges that the Covid-19 pandemic has brought about are mental health problems.

Following the increasing spread of the virus and the need to contain it, governments throughout the world, including the UK government, responded by putting in place various measures, including the restriction of internal or domestic movement through the institution of lockdowns, stay-at-home and physical social distance orders, closure (partial or total) of borders and travel bans which restricted international movements. These measures significantly affected people’s lifestyles and daily routines, as well as social interactions, as they had known them (Connor, 2020). Coupled with the economic impacts of the pandemic, including job losses and pay cuts, the measures aimed at containing the spread of the pandemic’s significant alteration of and impact on the global population’s social life acted as a catalyst for the development of mental health problems.

The coronavirus pandemic has affected millions of individuals globally and is expected to lead to significant mental health challenges among those who previous had no mental illnesses. It is also expected to exacerbate problems in those who have pre-existing mental health disorders and problems. Mental health challenges are likely to continue even after the pandemic is gone. Some of the factors linked to the disease which have been associated with its mental health impact on adults include experience of the virus, breakdown and or lack of social support, economic losses as well as stigma. These factors are linked both to short and long-term mental health challenges and issues (Chandola et al., 2020).

Chapter Two: Literature Review

The pandemic’s breakdown of social structures and its impact on mental healthContinue your exploration of Distance Education during COVID-19 with our related content.

Although much remains unknown with regard to the Covid-19 and the full extent of its consequences, it is expected that it will bring about profound and far reaching mental and physical health consequences (Candan, Elibol and Abdullahi, 2020). The possibility of the pandemic’s impact on mental health is demonstrated in part by evidence from China (Liu et al., 2020; Tian et al., 2020), as well as the experience of previous pandemics (Chan et al., 2006; Jeong et al., 2016). Preliminary evidence also points to the possibility of these experiences being replicated in the UK and across the world during the current pandemic (Williams et al., 2020). Apart from disrupting in an unprecedented manner the economy and the fabric of the society, the Covid-19 pandemic has also been shown to result in a host of challenges that have a high potential of significantly threatening our mental well-being (Holmes et al., 2020). One key component of our day-to-day life that significantly contributes to our stability is a structured day, which the Royal College of Psychiatrists (RCP) (2018) recommends as a factor that promotes mental health and well-being. However, as a consequence of the outbreak of the Covid-19 and its consequent growth into a global pandemic, as well as the measures taken by the UK and other governments to curb its spread and impacts, individuals’ ‘normal or structured day’ is seen to have been disrupted. For example lockdowns and restriction of gatherings result in people easily developing feelings of confinement and, with time, loneliness (Li and Wang, 2020). This loss of structure and disruption of a ‘normal day’ has the potential of giving rise to the development of unhealthy habits, such as excessive online gambling, gaming, alcohol consumption or substance use, as well as lack of exercise (Lopes and Jaspal, 2020). Due to lockdowns, people were forced to spend more time indoors and with their families- while this could be a positive outcome for some, it could also be stressful for others (Li and Wang, 2020). The economic impacts of the pandemic, including job losses and financial difficulties, have also been identified as factors likely to aggravate the development of mental health problems (Smith, Ostinelli and Cipriani, 2020). Whereas the lockdown is highly important with regard to the promotion of each individual’s health and safety, it also results in the separation of people from their friends and families, loss of freedom, as well as uncertainty (Gavin, Lyne and McNicholas, 2020; Vindegaard and Benros, 2020). According to the UK Office for National Statistics (ONS) (2020), key among the concerns that most people reported with regard to the lockdown were; personal well-being, employment and the impact that the pandemic had or would have on their finances, relationships, education and caring responsibilities. Additionally, about 50% of those surveyed also reported experiencing increased anxiety levels. Given their multi-factorial origins and the interplay between social, biological and psychological factors involved in the development of mental health problems, pandemics, such as the Covid-19, have been demonstrated to increase the likelihood of all these factors simultaneously coming into play (Smith et al., 2020).

Cases of mental health problems have already been reported in different countries including the United States and the United Kingdom. In the United States for example, 45% of the nation’s adult population reported cases of stress and anxiety, conditions which were increased by physical social distancing and fear of contracting the illness. On the other hand in the UK, about 33% of adults have experienced high anxiety levels since the pandemic began. A country like Italy, which was hit hard by the virus, experienced severe anxiety in 20% of its adult population, Insomnia in 7% of its adult population and depressive symptoms in17% of its adult population. These data show just how serious and negative the pandemic impacted and has the potential to affect the mental health of people around the world (Bu Steptoe and Fancourt, 2020).

According to Holmes et al. (2020), the effect of the coronavirus pandemic on people’s mental health is considered an important aspect of research and health going forward and that this impact should be given enough consideration in decisions about the spend, the time and how social distancing and lockdown restrictions are imposed and lifted (Layaerd et al., 2020). Early indicators, as identified by ONS (2020) through bespoke online surveys and cross-sectional studies on the virus indicate that there was lower subjective wellbeing levels and higher degrees of anxiety in the United Kingdom’s population compared to those found in 2019’s last quarter. Fancourt et al. (2020) note that this situation was sustained through the initial weeks of social distancing and the lockdown with some gradual and small improvements later after some weeks.

Following the establishment of associations between the Covid-19 pandemic and mental health it is important to determine who or the populations that might be at an increased risk of developing mental illnesses. According to findings by ONS (2020) and Zhou et al. (2020), the expectation is that individuals with an increased exposure to or likelihood of contracting the disease or at a higher risk of experiencing its adverse outcomes are likely to experience increased psychological morbidity. For instance, men and older people are known to have a higher death rate, with the elderly also being more likely to have underlying conditions which increase their vulnerability to the disease and likely mortality. Key workers, especially those in health and social care are also at an increased risk of Covid-19-related death (Zhou et al., 2020). These factors, though to a greater extent non-modifiable, contribute to individuals’ development of mental difficulties and/or illnesses. This is because the pandemic presents a challenging situation and acts as a stressor, resulting in individuals’ perceptions of their risk of contracting the disease as well as increased concerns regarding their safety, both of which are strongly associated with the likelihood of developing mental health problems or adverse mental health outcomes (Bults et al., 2011; Gao et al., 2020)

Smith et al. (2020), following their cross-sectional survey of UK adults who were self-isolating, concluded that poor mental health was significantly associated with self-isolating females, lower income individuals, younger people, smokers, as well as individuals with physical multi-morbidity. Another survey conducted by Rethink (a mental health charity in the UK) found that 42% of the respondents who were suffering from mental illness were of the opinion that the lockdowns following government’s effort to contain the spread of the Covid-19 had resulted in their conditions getting worse. Loades et al. (2020) also, following a rapid systematic review, posit that the social isolation that arises from the lockdown put children and adolescents at an increased risk of depression and anxiety.

Continue your journey with our comprehensive guide to Supporting Bushfire-Affected Communities through.

According to Banks and Xu (2020), it was clear there would be significant mental health impacts of the pandemic and the resulting social distancing and lockdown which were imposed on the people as a response to curb its spread. The health sector knew that the mental health was going to be one of the vital aspects of the coronavirus crisis. According to Kivimaki et al. (2017), the subjective wellbeing and mental health outcomes are important factors and risk factors for individual’s future longevity and physical health. Moreover, these factors can be the indication of a population’s future indirect impacts of pandemics. Additionally, wellbeing and mental health will drive and influence other individual behaviors, choices and outcomes (Kivimaki et al., 2017). In this literature review, the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic on various populations (women, young adults, children, the elderly, healthcare professionals and other frontline workers, patients and minority groups (immigrants), as well as access to counselling services will be explored.

Impact on women and young adults

Dunn, Allen, Cameron and Alderwirck (2020) claim that large changes have been witnessed in the UK citizens’ social life during this pandemic. Since the beginning of UK-wide lockdown on March 23rd 2020. Individuals were required to stay at home and provide reasonable excuses for to leave. The nation put in place tough lockdown conditions which were later relaxed with several regional variations. Most UK citizens passed through intense and severe social restrictions because of the disease. This lead to a rise in the number of potential stressors which impacted the mental health of a majority of adult population. Some of these stressors include those linked to the virus itself, like fear of contracting the illness. Others were indirect stressors because of the change in people’s social life, associated with the disruptions to people’s planned treatments, the economy’s shutdown and the increasing rate of unemployment and the associated financial stressors, new patterns of working, more home roles like child care, home schooling, and loneliness because of the lockdown conditions (Xue and McMunn, 2020).

Evidence show that the mental wellbeing and health of people in the United Kingdom worsened by the day during the pandemic and the imposed lockdown, with some groups becoming affected more than others. The wellbeing and mental health of women and young adults are reported to be worse affected during the coronavirus pandemic compared to men and older adults (Xu and Banks, 2020). These researchers note in their report that during the pandemic, a larger number of women reported being lonely. Additionally, they had greater levels of caring and family responsibilities, which made them to experience higher poor mental health levels than male adults (Etheridge and Spantig, 2020).

Etheridge and Spantig (2020) also found similar results with women, claiming that the lockdown due to the pandemic in many countries, including the UK, had significant impact on women’s mental health. According to this author, the pandemic increased the gap or inequality in people’s mental health with some groups having the poorest or worst mental health effects even pre-crisis. In their study, they also found that an increased prevalence of the virus led to an increase in mental health inequalities between different groups. Besides showing that specific groups suffered more due to the pandemic, these researches also claim that there is a difference in the magnitude or relative impact of the pandemic on the mental health of specific groups. According to these authors, some dimensions of people’s mental health suffered more than other dimensions and in some groups compared to others. According to Etheridge and Spantig (2020), while the measure s associated with people’s general happiness were affected across all ages, trends in some specific dimensions of people’s mental health were negatively affected, particularly in young individuals.

Breslau (2001) note that women are highly vulnerable to the impacts of traumatic incidences and the stress they experience because of the multiple responsibilities they have professionally and domestically. This is why nationwide survey in countries like China, Canada and the UK show that they are the most affected by the pandemic compared to the youth and men. Additionally, BioSpace (2020) support the findings which show that young adults were also affected by the pandemic. The authors note that young adults and adolescents are at increased risk of suicidal ideations and depression. According to Qiu et al. (2020), this group of people were more impacted by the information they received from different social media platforms, about the impact of the virus on people, the number of deaths which were being experienced and the fact that young people were likely to infect their elderly loved ones and even lead to their deaths. According to Xue and McMunn (2020), adults with children were likely to experience worse cases of mental health problems compared to those without kids. The author says that parents were afraid of the virus infecting their children. They experienced elevated concern for their children and high stress levels because of the fear, staying always on the lookout to protect their children from getting infected.

Banks and Xu (2020), in their study about the impact of social distancing and the lockdown in the first few months of the coronavirus pandemic in the UK say that the mental health of adults in this nation worsened by about 8.1%. These authors also note that the impact was mostly seen in women and young adults. These authors believe that this group had lower mental health issues before the pandemic. However, mental health inequalities still emerged, thanks to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Impact of the Pandemic on Healthcare professionals and frontline workers

Settings in the UK, the US, China and other parts of the world have reported serious mental health impacts of the pandemic on healthcare workers, first responders and frontline workers. These individuals reported significant cases of anxiety, clinical depression, suicidal ideations and post-traumatic stress (Rossi et al., 2020). In a study conducted by Liu and colleagues (2020) in China, it was found that 74% of the country’s professional workers suffered from post-traumatic stress, 36% had insomnia, and 45% had anxiety while 51% experienced anxiety. In this country, no difference was seen in the extent of mental health challenges experienced between healthcare professionals caring for patients suffering from the coronavirus and those caring for other types of patients (Liang et al., 2020). In other settings, healthcare workers, nurses and single doctors working in emergency rooms demonstrated greater predisposition to serious mental health challenges (Ho, Chee, Ho, 2019). In many settings including in UK hospitals, factors which affected the mental health of healthcare workers included the lack of sleep, discrimination, fear of contracting the virus and increased workload (Chen et al., 2020).

Healthcare workers caring for coronavirus patients isolated themselves from their loved ones to avoid the risk of infecting them. This in addition to the fear of contracting the virus led to lonely situations and significant mental health consequences, like depressive tendencies and suicidal ideations. As the number of individuals infected with the virus increased, workload for healthcare workers in UK hospitals and other countries where significant numbers of infections were high increased. The fewer number of doctors, nurses and other frontline workers in hospitals compared to the influx of infected patients requiring emergency care admitted to the hospitals meant that these professionals worked longer hours under the fear of getting infected. This led to exhaustion and fatigue with some becoming highly stressed and depressed. In a study conducted on Singaporean health workers by Chew et al. (2020), they were found with increased cases of lethargy, throat pain and headaches. To make matters worse for the health workers, some experienced discrimination. People were afraid of interacting with them because many believed that they might have been exposed to the virus. As a result, the health care workers were isolated and had few people to talk to and interact with. It means that the health workers, like those in the UK and other countries, suffered from mental health disorders because of these factors (Chen et al., 2020).

Impact of the pandemic on patients

According to Bo et al. 2020), most Covid-19 patients, mostly inpatients, suffered from posttraumatic stress disorders. In this research, it was found that these symptoms are likely to last for not less than two years, as shown by the previous SAR outbreak. Like SAR infection, Bo et al. (2020) found that the coronavirus pandemic would result in low life quality among those infected and their relatives. Gemelli et al. (2020) notes that coronavirus survivors are likely to have long-term challenges or consequences which will need multidisciplinary care, such as mental health treatment. Additionally, Li and Wang (2020) discovered that adults with coronavirus-related symptoms were also likely to report high loneliness and mental distress levels compared to those without such signs. Fancourt et al. (2020) also claims that adults who had pre-existing mental health problems similarly reported higher degrees of loneliness, depression and anxiety compared to those lacking pre-existing mental health challenges. Additionally, Wang et al. (2019) reported increased depression, anxiety and stress levels in people with some physical symptoms like coryza, dizziness and muscle aches, as well as those who believed that the status of their health is poor.

Rise in anxiety and depression in low income, minority grouped and immigrant adults

Wright, Steptoe, & Fancourt (2020) note that adults in low socioeconomic positions and low-income households also experienced more levels of depression and anxiety than those from higher socioeconomic positions and household income. According to these authors, adults lacking employment were likely to show increasing loneliness levels. Additionally, those who lost their income earlier as the lockdown began also reported similarly higher mental distress and anxiety levels. High stress levels have also been witnessed among migrant workers because of the income uncertainty and their levels of exposure to the virus (Qiu et al., 2020). Qiu et al. (2020) note that these individuals demonstrated increased depression, anxiety and stress.

In the US and the UK, reports show that individuals earning low wages had higher mental health challenges compared to high-income earners (Panchal et al., 2020). Low income earners lacked enough money to stock up food and other essentials needed to survive the lengthy lockdowns. The lack of sufficient food and other important essentials led to a strain and serious physical and mental difficulty in this group. This is the same situation which individuals who lost their jobs went through. The inability to pay for rent/mortgage meant that some people were at risk of losing their houses and livelihoods, especially for those who lost their jobs or businesses. These situations led to stress, anxiety, depression and even posttraumatic stress (Panchal et al., 2020).

High stress levels in educated adults

Niedswiedz et al. (2020) also found significantly higher levels of mental distress in employed adults, especially those with higher education levels. According to Niedswiedz et al. (2020), the impact of some particular stressors like those linked to finances and unemployment on the mental health of adults might have increased even after the initial lockdown as employers and business grappled with tough economic consequences that came about when the economy was shut. Qiu et al. (2020) support the findings that educated adults were mostly affected by the pandemic. The authors claim that this is because this group of individuals experienced increased stress levels because they are highly self-aware about their health. They understand how the virus is spread and how it can affect their bodies and their loved ones. This awareness increased their fear for the virus and caused increased stress levels.

Impact of the pandemic on the mental health of the elderly

It has been shown that older adults are at increased risk of mental health challenges because of the pandemic (BioSpace, 2020). Countries like China and the UK have older populations with pre-existing depression. With the pandemic and the associated social distancing and lockdown, their depression worsened. BioSpace (2020) highlight that this group of people were also like to suffer from the fear of dying from the virus, a situation which would lead to the worsening of their mental health and stressful times. These findings are contrary to those in a study conducted in Canada and the US which found less mental health disorders or problems in seniors above 65 years old compared to other population segments (BioSpace, 2020). No reasons were, however, given for this contrasting finding.

How access to counseling has been effected by the lockdown

According to Duan and Zhu (2020), the pandemic disrupted health care systems in many countries around the world. This research shows that Covid-19 affected the care of other patients suffering from chronic illnesses and who required visiting physical healthcare premises to receive chronic care. In the UK, mental health care is usually accessed through local General Practitioners (GPs). However, because of the infectious nature of the virus, spreading easily through air, face to face appointments was halted in most secondary care facilities for other patients, and GPs started to advice their patients not to physically visit the facilities. Instead, the sessions were conducted via the telephone, of which telephone calls were also screened to establish the priority of the patients’ clinical need- this further contributed to negatively affecting people’s access to mental health. This led to high stress levels for the patients who needed chronic care but could not visit hospital and be treated in a timely manner (Duan and Zhu, 2020). This situation also affected psychiatric patients, particularly those who were already experiencing suicidal ideations, stress, anxiety and depression (Hao et al., 2020). Other patients who suffered because of the social distancing and the lockdown are those suffering from bipolar disease and schizophrenia. The lack of free movement, and reduced socialization had an impact both on their physical and mental health. Hao et al. ( 2020) note that this is so especially because these patients often depend on regular visits to healthcare facilities and the regular clinical contacts with mental health professionals for support.

Factors facilitating the mental health disorders in adults

Evidence shows that there are three main factors which affect populations and result in mental health difficulties in adults. According to Institute for Social and Economic Research (2020), the direct effect or impact of the virus, especially near-death experiences for individuals diagnosed with the illness has been found to cause significant mental health effects on individuals. These individuals not only suffered from the thought of having a deadly virus but were also isolated from their loved ones, a difficult experience for both the patients and members of their families. Families who lost their loved ones because of the virus, are reported to have particularly suffered serious mental health problems including stress, anxiety, depress and posttraumatic stress. Additionally, the discrimination and stigma associated with the virus impacted survivors’ mental health significantly (Institute for Social and Economic Research, 2020).

Governments put in place measures to stop the virus from spreading. Such measures included limiting or restricting physical interactions. Limited access to important social support amenities, inadequate medication and food supply and reduced access to important treatment for individuals with serious mental health conditions and diseases like cancer, reduced access to churches, mosques and other faith-based institutions and reduced access to leaders and law enforcement institutions led to an increased level of mental health problems for those requiring those services (University of Essex, Institute for Social and Economic Research, 2020). In many communities have social structures which keep people together and provide support to those in need, especially those with illness and the elderly. The lockdown and the social distancing directives affected these structures and led to loneliness among the groups that are vulnerable to mental health challenges (University of Essex, Institute for Social and Economic Research, 2020).

One area that was hit hard resulting in stress and uncertainty is jobs (International Monitory Fund, 2020). Many people working both in the informal and formal sectors lost their jobs. While governments put in place measures to shield individuals working in the formal sectors from financial difficulties, most of those in informal activities were not eligible for the schemes (International Monitory Fund, 2020). One of the areas that was significantly affected by this virus is the agricultural sector, where a significant number of informal workers are situated (Joyce and Xu, 2020). According to Joyce and Xu (2020), this sector has been hit hard by the pandemic and the imposed lockdown which affected their perishable goods. The lockdown led to huge loses in the sector since their goods could not reach the market because of the lockdown. Besides this leading to the loss of livelihoods for many people working in the sector, this also led to a shortage in food supply, affecting many people who depend on agricultural produce for food. This situation led to mental health problems like stress and depression (Joyce and Xu, 2020).

Conclusion

Evidently, the pandemic affected all people at a global scale. Access to important essential services, food and leadership was affected. Those with pre-existing mental health difficulties suffered significantly with their conditions being worsened. Women also suffered mental health challenges because besides worrying about their professions, those with families and children had multiple roles, increasing pressure and mental stress. Different sectors, both formal and informal were affected, with job loses that led to increased stress and depression. Low-income earners and migrant workers suffered from job uncertainty increasing their stress levels. Healthcare professionals and frontline workers also suffered a hit with increased workload, discrimination, fear of contracting the virus and fatigue causing more stress, anxiety, depression and suicidal ideations.

Chapter Three: Methodology

Introduction

The successful completion of a study requires the researcher adopts appropriate and suitable strategies and methods, whose choice will be influenced by the type and scope of the study. The employment of the most appropriate methods will result in the study effectively achieving its goals and objectives. Besides the type and scope of study, the choice of research methods will also be impacted on by the time available to the researcher for the completion of the research and the environment in which the research is conducted (Quigley and Notarantonio, 2015). A researcher therefore needs to possess and draw on their knowledge and understanding of the numerous research methods and how they apply to the different types of studies. In addition, they must appreciate that the various methods are unique and apply or are suitable to certain types of studies and that no one particular method can be used for all studies.

In order to explore the impacts that the Covid-19 pandemic has had on various categories of the population in relation to their mental health, as well as affected access to counselling services and the consequence of this, the systematic research approach will be employed. This approach has repeatedly demonstrated its ability to result in transparency (which is brought about by the extensive evaluation of the relevance and quality of the body of knowledge and research materials used) with regard to the way in which the study generates or develops its conclusions. The significance of the systematic research approach and the transparency it facilitates is that the likelihood of misinterpretation or lack of clarity among the study’s readers or even the researcher regarding the knowledge base that has been used (Wahyuni, 2012). The approach, through its clear emphasis of the steps followed by the researcher to conduct the study, minimizes the possibility of employing unsuitable or less appropriate methods which would result in the obtaining of distorted or inaccurate results, thereby enhancing the study’s findings and thus, its overall quality (Faux, 2012). Wahyuni (2012) also asserts that the systematic approach also results in the study’s explicitness and the potential of readers to gauge if the researcher was thorough and achieved their objectives.

Research philosophy

Research philosophy influences the quality of the data that is collected when conducting a research, and is therefore a key aspect of research (Mackey and Gass, 2015). Researchers must therefore select and employ a research philosophy that is highly appropriate to the type of study being conducted as it will markedly impact on the study’s overall quality. Wahyuni (2012) identifies the three most popular research philosophies as interpretivism, realism and positivism, and notes that each is advantageous and disadvantageous depending on the type of study it is employed in. To complete and accomplish the objectives of this study, the researcher chose to adopt the positivist research philosophy. This is due to its proven ability to do away with the likelihood of researchers being biased during their data collection activity thus, encouraging their objectivity, which sequentially contributes to the minimization of likely margins of error in the findings of study that would originate from a prejudiced data collection (Verschuren, Doorewaard and Mellion, 2010). As a result of its employment of positivism, the findings obtained by the study can be regarded as truly and accurately demonstrating the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic and its effects on access to psychiatric counselling.

Research Approach

Research approach indicates the plan of action and process that underscores the study’s general assumptions and the key strategies it employs in the collection and analysis of data, as well as presentation of findings in a manner that results in the attainment of its aims. According to Mantere and Ketokivi 92013) deductive research approach and inductive research approach are the two most common research approaches, and the choice of either is significantly predicted by the type of study and the availability and accessibility of the data needed to complete the study. The deductive research approach is normally employed in instances where the data needed to complete a study is readily available and can be accessed easily, whereas the inductive research approach is used in situations where the necessary data not readily available or easily retrievable. Due to the newness of the Covid-19 pandemic and relatively limited body of knowledge on the topic, this study will employ the inductive research approach. Through the inductive approach, the researcher will be able to identify patterns from their observations relating to the topic and then develop explanations/theories for the observed patterns through multiple hypotheses (Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill, 2012). This way, the researcher will use the data collected to generate meanings so as to identify patterns and associations to develop theories (Bernard, 2011).

Research Design

Research design describes the process followed by the researcher to conduct the study and answer the research questions asked by the study (Creswell and Poth, 2017). One or more research designs can be used in combination, depending on the type of study being carried out, and the most common ones are: descriptive, cross-sectional, longitudinal, exploratory, explanatory, and so on (Eastwood, Jalalulin and Kemp, 2014). For the effective investigation of the current study topic, the researcher chose to use a combination of the cross-sectional and descriptive designs. Through the descriptive design, the recognition and elucidation of people’s beliefs, values, attitudes, behaviors, perceptions and thoughts relating to the study topic is made possible (Gray, 2019). The researcher chose the descriptive design given its enhancement and reinforcement of reasonableness and accuracy of the interpretation of the findings obtained, thereby making it suitable for this study which is a fact-finding one. As a result of the time and resource constraints and the limited time available for the completion of the study, the study’s objectives and resulting convenience, the researcher also chose to use the cross-sectional research design through which the necessary data is collected within one time period (Sekaran and Bougie, 2016). Using the two designs together will significantly improve and enhance the overall quality of the study, and thus its validity and credibility (Rahi, 2017).

Data Collection

Data collection is a critical phase of the research process since without it, it would be difficult or impossible to effectively complete a study. Thus, researchers must take into account the type of study they are carrying out since this will influence the type of data they will need to collect as well as their degree of availability and access. The data collected and used in conducting a research can generally be categorized as either primary or secondary data. In this case where research is primary, the researcher will collect primary data. Primary data is that which researchers collect direct from the source and in real-time (while conducting the study) (Driscoll, 2011). Given that primary data purposes to generate specific explanatory information that is explicative of the topic being investigated, this study will utilize the specificity brought about by primary data to effectively address its research questions (Norris et al., 2015). Various primary data collection methods exist, including observations, surveys/questionnaires, interviews and experiments. The researcher chose to employ questionnaires as the data collection method of choice. The questionnaires, which will accommodate both closed and open-ended questions, were chosen because of their facilitation of the capacity to collect broad-spectrum of data from a sizeable sample size in an easier, more convenient, quicker and cost-effective manner (Testa and Simonso, 2017). Questionnaires have also been illustrated as an effective technique that has the potential of minimizing or eliminating the possibility of the researcher wrongly or inaccurately interpreting the responses given by the participants of the study or the study’s findings (Gray, 2019).

Target Population

The target population describes the entire unit or group of individuals from whom the study aims to draw conclusions and generalize its findings to. Uprichard (2013) suggests the adoption of the most suitable sampling strategies in order for the researcher to obtain and draw on the appropriate sample size in relation to its quantity and qualitative attributes. To obtain the needed sample size, a researcher can adopt either probability or non-probability categories of sampling techniques. The researcher adopted the use of both probability and non-probability techniques. The non-probability technique he employed was the purposive sampling method through which he identified participants who exhibited certain characteristics (Zhi, 2014), for example psychiatrists, counsellors and mental health nurses, as well as patients suffering from mental disorders or in need of psychiatric services. He also used the probability sampling technique (random sampling method) to randomly identify participants (women, young people, older adults, etc) from whom he would collect data relating to how the Covid-19 pandemic had impacted on the various aspects of their lives. Through this combination of sampling strategies, the researcher identified and recruited a total of 150 respondents.

Data Analysis and Presentation

Due to the use of primary data that is descriptive and also qualitative, the descriptive statistical analysis method will be used in conjunction with Microsoft Excel for the analysis of the collected data. The findings arising from the analysis of data will then be presented using tables, percentages, pie charts, bar graphs, among other visual charts.

Ethical Considerations

Before they could take part in the study, the participants needed to give their written informed consent. They were also guaranteed their anonymity and the privacy and confidentiality of their information, as well as the use of their responses for no other purpose besides purpose of this study and that no one outside the research team could access them. In addition, they affirmed to their ability and right to withdraw from the research at any point.

Chapter Four: Results

Introduction

The researcher began by collecting demographic data. The collection of demographic data from research participants is necessary as it facilitates determining whether the involved participants are representative of the target populations sample for purposes of generalisation. When demographic information is not included, the risk of assumption of the “absolutism” stance comes about (Conelly, 2013). This stance makes an assumption that the phenomena of interest are the same giving zero regard to socioeconomic status, gender, and age. When detailed information on the characteristics of participants is provided, that enables researchers to move towards a “universalism” position which recognises the presence of universal psychological processes that manifest in different ways, dependent on different participant`s characteristics (Bhargava, 2020).

There are differences that exist between groups and this is proven through the collection of demographic data. In addition, by thoroughly describing participants, researchers and readers are put in a better position to determine to whom research findings generalise, and through this allowing for the making of comparisons across replication of studies (Beiser-McGrath and Huber, 2018). Also, necessary data for secondary data analyses and research synthesis is also provided.

Section One: Demographics

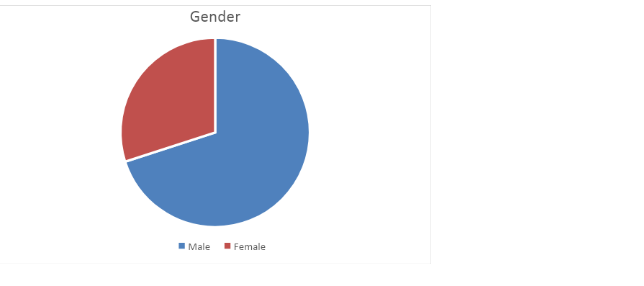

While the researcher had initially identified 150 possible participants, due to time limitations, only ten were involved in the study. These ten were selected through simple random sampling of the initial sample. When asked about their gender, 7 (70%) of the participants reported being male, while 3 (30%) said they were male.

The participants were then asked about their employment status, to which 6 (60%) reported being employed and 4 (40%) said they were not employed.

The participants were then asked about their professions. Out of the six employed respondents, the majority were carers, 3 (50%), 1 was a counsellor, 1 a bar staff and 1 was a professional support worker in mental health.

The respondents were asked about their academic qualifications. The majority of them had high school qualifications which were the lowest qualifications, another considerable lot, precisely six respondents had college certificates, 2 participants had college diplomas, 1 was an undergraduate and two were post-graduate.

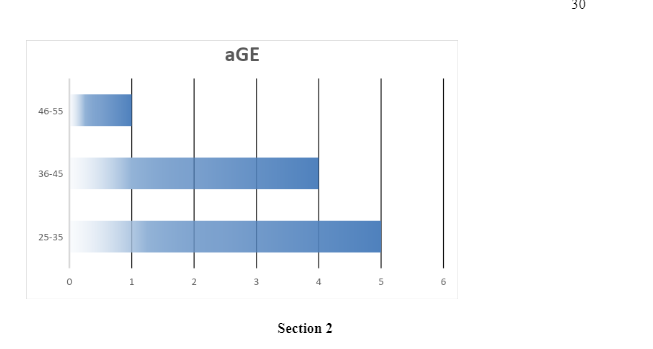

The respondents were then asked about their ages. 5 (50%) of the respondents were aged between 25 – 35 years, 4 (40%) were aged between 36 – 45 years, while 1 was aged between 46 and 55 years. None of the respondents was aged between 18-25 years, 25-35 years, or above 55 years.

The participants were then asked about the different impacts the pandemic had had on them and their households. 5 of the respondents said that they had been affected through loss of their jobs, 6 reported that they had been affected by being sent for partial or furlough leaves, loneliness was commonly reported by all the participants, 9 participants reported changes in work patterns, and 9 also reported disruptions in their social lives.

The participants where then asked whether they felt like the pandemic had contributed to an increase in mental health incidences among the general population. All the respondents said that the pandemic had resulted in an increase in the incidences of mental health problems. The respondents equally attributed these mental health problems to lockdowns and movement restrictions, stay at home measures, fear of contracting the virus and the pandemics social, health and economic impacts.

An enquiry was subsequently made on the type of mental disorders that the participants or the people who they knew or were close to them were suffering from. Anxiety was reported as the most common mental disorder, with 9 of the respondents ticking against anxiety. A significant portion of the participants, 8 to be precise reported depression, 6 reported mood disorders, 4 reported sleeping disorders, 1 reported emotional problems and 1 reported addictive disorders.

An enquiry was subsequently made as to whether these effects came about before or after the pandemic. All the respondents said that these impacts came by after the onset of the pandemic, while 4 responded that they had also experienced the problems before the pandemic.

The researcher then enquired from the participants, specifically those who worked as healthcare providers and frontline workers, the effects the pandemic had had on their performance of duty and care to Covid-19 and also non-Covid-19 patients. 5 out of the employed respondents were healthcare workers. The remaining participant who was not a healthcare worker but worked as a bar staff was required to identify the different ways through which the provision and access to psychiatric treatment and counselling among patients with mental health illnesses had been affected. The participant ticked against all the options including reduced access to counselling due to lockdowns and movement restrictions, limitation of face-to-face counselling appointments/sessions, scaling down of counselling/psychiatric services to provide more room for the management of Covid-19 patients and the reduction of the available funds to cater for psychiatric/counselling costs due to job losses and pay cuts.

In the midst of acute health crises, healthcare services are put under excessive pressure which makes life more stressful. There are very many patients during the pandemic who require treatment and this places even more strain on mental health workers. Healthcare workers also perceive increased risks due to getting exposed to patients with the pandemic. The provision of medical care in the midst of the pandemic has generated fear and heightened stress levels among health workers. These health workers are exposed to increased risks of infection, dying and death, moral dilemmas related to making decisions on those who qualify for intensive care, and increased workloads. These experiences have the potential of being traumatising and contribute to increased mental health risks in groups of mental health workers who are already at risk. There is the possibility of psychological effects being variable across different studies which demonstrates a higher risk of acquisition of trauma and stress-related disorders. In this study, the participants reported symptoms of anxiety, post-traumatic stress, insomnia, and depression. The participants also reported increments in their workload, and reported dear of the virus and contracting it. The problems in insomnia are reported in other different studies. Being proximal to cases of Covid-19 has been associated with worsened quality of sleeping with various studies reporting that healthcare workers and frontline workers experience poor quality of sleep and increased severity of insomnia.

There are also studies that have reported additional outcomes including psychological trauma, burnout at workplaces and distress. Among healthcare workers, there are increased levels of exhaustion within workplaces and increased prevalence of fatigue. The study also established differences by age with the younger healthcare workers experiencing relatively higher anxiety, depression, insomnia, and post-traumatic stress. The study also established differences between female and male health workers and women experienced more of these symptoms when they were compared to men.

Chapter Five: Discussion

The findings of this study reveal that Covid-19 has had significant effects on people`s mental health. The symptoms of anxiety and depression have been the most common. The findings of this study are common to other studies that have been carried out in other different places. A study carried out on an Iranian population found that anxiety, depression and anxiety were common among the population as a result of Covid-19 (Garcia-Fernandez et al. 2020; Khan et al. 2020; Chatterjee et al. 2020; Pfefferbaum, 2020). Many people have been facing challenges that have the potential of being overwhelming, stressful and causing relatively strong emotions among individuals. People have the tendencies of getting more anxious and feeling unsafe whenever there are changes in their environments (Mann et al. 2020). Especially, with the outbreak of infectious diseases which are characterised by unclear outcomes, the levels of anxiety rise significantly.

The findings of this study also point to increased prevalence of loneliness as a result of Covid-19. With the imposition of different rules aimed at ensuring physical distancing, the prevalence of loneliness increased and this could have had an effect on the exacerbation of existing mental health conditions (Wickens et al. 2021). Different challenges for the management of loneliness feelings are presented by the Covid-19 pandemic. Different studies examining the effects of quarantine have established that many people have struggles to adapt to ways of life that are not congruent with the social nature of human beings and reported different negative psychological reactions to quarantine, for example, loneliness (Groarke et al. 2020; Killgore et al. 2020; Rosenberg et al. 2020). One of the most important risk factors for loneliness is limited social interaction.

This study also found out that different restrictive measures put up to contain the spread of Covid-19, effectively limiting physical interactions acted to worsen mental health. These measures effectively limited access to social support structures,

There are different ways through which the pandemic has likely had effects on mental health, and in particular with the increased social isolation that results from the different necessary safety measures that have been put in place. There is extensive research that links loneliness and social isolation to worsened mental health (Hwang et al. 2020; Pancani et al. 2020; Robb et al. 2020).

This study further found out that the pandemic has led to disruptions of social life. This disruptions are observed to have been brought about by the different restrictive measures that have been put in place by governments aimed at curbing the virus` spread, including the limitation of movements, enforced quarantine, closure of public spaces, and enforcement of social distancing. These measures have brought about different economic impacts as found in this study including the loss of jobs. Out of the 10 respondents, 5 (50%) said that the pandemic had led them or a member of their household to lose their jobs. From the findings of this study, it is quite clear that during the pandemic there was a considerable number of people that were refrained from going outside, got suspended or lost their jobs and began working from home. The majority of the participants also confessed to either them or members of their families having been sent for partial or furlough leaves owing to the pandemic.

The pandemic also brought about changes to work patterns. At the height of the pandemic back in 2020, up to half of the globe`s workforce was working remotely. However, continuous remote working has been reported to extend work days, diffuse work-life boundaries and additionally reduce mental wellbeing. A study by Sato et al. (2020) was carried out to examine how work-related changes brought about by the pandemic were associated with depressive symptoms. The study established that reduced weekday steps during the period of declaration had associations with increased depressive symptom odds. For work related purposes, at times, face-to-face interactions become necessary as they facilitate the building of collaborations, building relationships, solving challenges that are complex and generating ideas (Prasada and Vaidya, 2020). Working from home has however, not been bad entirely. Different studies have reported that it is possible to accomplish majority of work related tasks remotely with no significant drops in quality and productivity (Beland et al. 2020; Crowley and Doran, 2020; Wang et al. 2021).

The participant who did not work in the healthcare sector admitted that Covid-19 had limited their access to psychiatric treatment and counselling among patients with mental health illnesses. This happened through reduced access to counselling as a result of restrictions on movements and lockdowns, limitations of face-to-face counselling sessions, scaling down of counselling/psychiatric services for purposes of providing more room for management of patients with Covid-19 and reduction in the funds available for catering for the costs of psychiatric counselling as a result of pay cuts and job losses. From this is evident that the pandemic has effectively disrupted and in some instances entirely altered critical mental health services, while there has been an increase in the demand for mental health care. The increased demand has been triggered by income losses, fear of contracting the disease, uncertainties about the future, and bereavement. A survey carried out by the WHO in August 2020 to evaluate the different ways through which Covid-19 had changed the provision of mental, neurological and substance use services, reported extensive disruptions to access of critical mental health services (WHO, 2020). The survey reported that mental health services for vulnerable people had been disrupted by over 60%, with 67% of these disruptions being on psychotherapy and counselling, 65% to services aimed t reducing critical harm and 45% to treatment of dependence on opioids. The survey also reported disruptions in workplace and school mental health services. A study by Ahmed et al. (2020) that sought to determine the impacts of Covid-19 societal responses on healthcare for non-Covid-19 related issues reported that the abilities of slim residents to seek healthcare for conditions that had no relationship with Covid-19 had been diminished.

Conclusion

The current study found that Covid-19 has had immense effects on people`s mental health. For complete recovery from the pandemics negative impacts, plans have to be put in place to address the mental health issues that people and mental healthcare professionals face. There is need for public health surveillance during the course of the pandemic and even after the pandemic to include plans for surveillance of mental health for purposes of allowing for adequate responses to the mental health issues that are anticipated. Without a doubt, good mental health is quite fundamental for well-being and overall health.

The leaders of different healthcare organizations also have roles to play and a very important role is played by communication. Organizations have to ensure that they provide their staff with evidence-based information that is accurate and timely on Covid-19 and the response to be taken by the hospital, including the worst case scenarios. Effort should be put to ensure that there is visible leadership that is also easily recognisable. Regular communication should also be provided and this should come with the opportunities of doing regular check-in`s and discussions. Healthcare workers should be provided with autonomy and input into the making of decisions in all possible instances and bureaucratic hindrances should be removed to make their work more flexible and enable them to work with minimal pressure.

With time, the pandemic will become a thing of the past. However, its mental health effects on the well-being of general populations, healthcare professionals and people who are vulnerable will be there for long. Governments and authorities will need to continuously show strong leadership and also be supportive to healthcare workers to be able to deal with the pandemic`s mental health issues in addition to supporting the mental health workers and their families. One of the ways through which this can be achieved is through the deliberate actions of adding healthcare staff mental health support process as ongoing agenda items for policy planning.

For purposes of reducing the mental health risks of Covid-19, the following recommendations would be helpful.

- Isolation should be broken, that is, communication with family members, friends, and loved ones should be increased even when there are distances. The loneliness could be reduced through video-chats and group calls. And in the event people have limited social networks, professional helplines could come in handy but they have to be managed by professionals who possess proper training.

- People should also be advised to maintain their normal life rhythms. Maintenance of regular routines by means of having diet patterns and sleep-wake routines.

Limitations of the study

The study had a relatively small sample size of only 10 participants. Small sample sizes have effects on the reliability of the results of a survey and that is because these samples lead to increased variability, which could bring about bias. Appropriate sample sizes are necessary for validity. Whenever the sample sizes are too small, the results yielded end up lacking validity. In addition, the results from small sample sizes are often questionable. A larger sample size would have produced more valid results.

References

Bakar, N.A. and Rosbi, S., 2020. Effect of Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) to tourism industry. International Journal of Advanced Engineering Research and Science, 7(4), pp.189-193.

Beiser-McGrath, L.F. and Huber, R.A., 2018. Assessing the relative importance of psychological and demographic factors for predicting climate and environmental attitudes. Climatic change, 149(3), pp.335-347.

Béland, L.P., Brodeur, A. and Wright, T., 2020. The short-term economic consequences of Covid-19: exposure to disease, remote work and government response.

Bhargava, A., 2020. RE: On the importance of demographic variables and longitudinal data analyses in climate change research.

BioSpace, 2020. New Study by Teladoc Health Reveals COVID-19 Pandemic’s Widespread Negative Impact on Mental Health. https://www.biospace.com/article/releases/ new-study 560 -by-teladoc-health-reveals-covid-19-pandemic-s-wide spread-negative-impact-on-mental-health/ [Accessed 2nd March 2021]

Bo HX, Li W, Yang Y, et al., 2020. Posttraumatic stress symptoms and attitude toward crisis mental health services among clinically stable patients with COVID-19 in China [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 27]. Psychol Med. 1–2. Doi: 10.1017/ S0033291720000999. [Accessed 2nd March 2021]

Breslau N., 2001. The epidemiology of posttraumatic stress disorder: what is the extent of the problem? J Clin Psychiatry. 62(Suppl 17):16–22.

Bu, F., Steptoe, A., & Fancourt, D., 2020. Loneliness during a strict lockdown: Trajectories and predictors during the COVID-19 pandemic in 38217 United Kingdom adults. Social Science & Medicine, 265, 113521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113521. [Accessed 2nd March 2021]

Bults, M., Beaujean, D.J., de Zwart, O., Kok, G., van Empelen, P., van Steenbergen, J.E., Richardus, J.H. and Voeten, H.A., 2011. Perceived risk, anxiety, and behavioural responses of the general public during the early phase of the Influenza A (H1N1) pandemic in the Netherlands: results of three consecutive online surveys. BMC public health, 11(1), pp.1-13.

Candan, S.A., Elibol, N. and Abdullahi, A., 2020. Consideration of prevention and management of long-term consequences of post-acute respiratory distress syndrome in patients with COVID-19. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 36(6), pp.663-668.

Chan, S.M.S., Chiu, F.K.H., Lam, C.W.L., Leung, P.Y.V. and Conwell, Y., 2006. Elderly suicide and the 2003 SARS epidemic in Hong Kong. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry: A journal of the psychiatry of late life and allied sciences, 21(2), pp.113-118.

Chandola, T., Kumari, M., Booker, C.L. and Benzeval, M.J., 2020. The mental health impact of COVID-19 and pandemic related stressors among adults in the UK. medRxiv.

Chatterjee, S.S., Malathesh Barikar, C. and Mukherjee, A., 2020. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on pre-existing mental health problems. Asian journal of psychiatry, 51, p.102071.

Chen Q, Liang M, Li Y, et al, 2020. Mental health care for medical staff in China during the COVID-19 outbreak [published correction appears in Lancet Psychiatry. 2020 May; 7(5):e27]. Lancet Psychiatry.7 (4):e15–e16. Doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30078-X [Accessed 2nd March 2021]

Chew NWS, Lee GKH, Tan BYQ, et al., 2020. A multinational, multicentre study on the psychological outcomes and associated physical symptoms amongst healthcare workers during COVID-19 outbreak. Brain Behav Immunol. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.049 [Accessed 2nd March 2021]

Connelly, L.M., 2013. Demographic data in research studies. Medsurg Nursing, 22(4), pp.269-271.

Creswell, J.W. and Poth, C.N., 2017. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. London: Sage publications.

Crowley, F. and Doran, J., 2020. COVID‐19, occupational social distancing and remote working potential: An occupation, sector and regional perspective. Regional Science Policy & Practice, 12(6), pp.1211-1234.

Duan L, Zhu G., 2020. Psychological interventions for people affected by the COVID-19 epidemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 7(4):300–302. Doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30073-0 [Accessed 2nd March 2021]

Dunn, P., Allen, L., Cameron, G., & Alderwick, H., 2020. COVID-19 policy tracker. London: The Health Foundation. https://www.health.org.uk/ news-and-comment/charts-and-infographics/covid-19-policy-tracker. [Accessed 2nd March 2021]

Eastwood, J.G., Jalaludin, B.B. and Kemp, L.A., 2014. Realist explanatory theory building method for social epidemiology: a protocol for a mixed method multilevel study of neighbourhood context and postnatal depression. SpringerPlus, 3(1), p.12.

Etheridge, B., & Spantig, L., 2020. The gender gap in mental well-being during the Covid-19 outbreak: Evidence from the UK (ISER Working Paper Series No. 2020-08). Institute for Social and Economic Research. https://econpapers. repec.org/paper/eseiserwp/2020-08.htm. [Accessed 2nd March 2021]

Fancourt, D., Bu, F., Mak, H-W, and Steptoe, A., 2020. Covid 19 Social Study: Results release 11, UCL mimeo. https://www.covidsocialstudy.org/results [Accessed 2nd March 2021]

Gao, J., Zheng, P., Jia, Y., Chen, H., Mao, Y., Chen, S., Wang, Y., Fu, H. and Dai, J., 2020. Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. Plos one, 15(4), p.e0231924.

García-Fernández, L., Romero-Ferreiro, V., López-Roldán, P.D., Padilla, S., Calero-Sierra, I., Monzó-García, M., Pérez-Martín, J. and Rodriguez-Jimenez, R., 2020. Mental health impact of COVID-19 pandemic on Spanish healthcare workers. Psychological medicine, pp.1-3.

Gavin, B., Lyne, J. and McNicholas, F., 2020. Mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic. Irish journal of psychological medicine, 37(3), pp.156-158.

Gemelli, 2020. Against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Study Group. Post- COVID-19 global health strategies: the need for an interdisciplinary approach [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 11]. Aging Clin Exp Res. 1–8. Doi: 10.1007/s40520-020-01616-x [Accessed 2nd March 2021]

Gray, D. E., 2019. Doing research in the business world. Sage Publications Limited.

Groarke, J.M., Berry, E., Graham-Wisener, L., McKenna-Plumley, P.E., McGlinchey, E. and Armour, C., 2020. Loneliness in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-sectional results from the COVID-19 Psychological Wellbeing Study. PloS one, 15(9), p.e0239698.

Handbook of Pschosocial Epidemiology. Abingdon: Routledge, Routledge Handbooks Online, https://doi.org/:10.4324/9781315673097. [Accessed 2nd March 2021]

Hao F, Tan W, Jiang L, et al., 2020. Do psychiatric patients experience more psychiatric symptoms during COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown? A case-control study with service and research implications for immunopsychiatry. Brain Behav Immunol. 87:100–106. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.069 [Accessed 2nd March 2021]

Ho C, Chee C, Ho R., 2020. Mental health strategies to combat the psychological impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) beyond paranoia and panic. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 49:1–3.

Holmes, E. A., O’Connor, R., Perry, V. H., Tracey, I., Wessely, I., Arseneault, L., Ballard, C., Christensen, H., Silver, R. C., Everall, I., Ford, T., John, A., Kabir, T., King, K., Madan, I., Michie, S., Przybylski, A. K., Shafran, R., Sweeney, A., Worthman, C. M., Yardley, L., Cowan, K., Cope, C., Hotopf, M., Bullmore, E., 2020. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science, Lancet Psychiatry, 7, 547–60

Holmes, E.A., O'Connor, R.C., Perry, V.H., Tracey, I., Wessely, S., Arseneault, L., Ballard, C., Christensen, H., Silver, R.C., Everall, I. and Ford, T., 2020. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. The Lancet Psychiatry.

Hwang, T.J., Rabheru, K., Peisah, C., Reichman, W. and Ikeda, M., 2020. Loneliness and social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Psychogeriatrics, 32(10), pp.1217-1220.

Institute for Social and Economic Research (2020). Understanding Society COVID-19 User Guide. Colchester: University of Essex.

International Monitory Fund, 2020. Policy responses to COVID-19. https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-and-covid19 /Policy-Responses-to-COVID-19 [Accessed 2nd March 2021]

Jeong, H., Yim, H.W., Song, Y.J., Ki, M., Min, J.A., Cho, J. and Chae, J.H., 2016. Mental health status of people isolated due to Middle East Respiratory Syndrome. Epidemiology and health, 38.

Joyce, R. and Xu, X., 2020. Sector shutdowns during the coronavirus crisis: which workers are most exposed? London: IFS. https://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/14791 [Accessed 2nd March 2021]

Khan, K.S., Mamun, M.A., Griffiths, M.D. and Ullah, I., 2020. The mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic across different cohorts. International journal of mental health and addiction, pp.1-7.

Killgore, W.D., Cloonan, S.A., Taylor, E.C., Lucas, D.A. and Dailey, N.S., 2020. Loneliness during the first half-year of COVID-19 Lockdowns. Psychiatry Research, 294, p.113551.

Kivimäki, M., G. Batty, A. Steptoe and I. Kawachi, 2017. The Routledge International

Layard, R., D. Fancourt, A. Clark, N. Hey, J-E De Neve, G. O’Donnell and C.Krekel, 2020. When to release the lockdown? A wellbeing framework for analysing costs and benefits. IZA Discussion Paper No 13186. https://ftp.iza.org/dp13186.pdf [Accessed 2nd March 2021]

Li, L. Z., & Wang, S., 2020. Prevalence and predictors of general psychiatric disorders and loneliness during COVID-19 in the United Kingdom. Psychiatry Research, 291, 113267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113267 [Accessed 2nd March 2021]

Liang Y, Chen M, Zheng X, Liu J., 2020. Screening for Chinese medical staff mental health by SDS and SAS during the outbreak of COVID-19. J Psychosom Res. 133:110102. Doi: 10.1016/j. jpsychores.2020.110102 [Accessed 2nd March 2021]

Liu S, Yang L, Zhang C, et al, 2020. Online mental health services in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Psychiatry. 7(4):e17– e18. Doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30077-8 [Accessed 2nd March 2021]

Loades, M.E., Chatburn, E., Higson-Sweeney, N., Reynolds, S., Shafran, R., Brigden, A., Linney, C., McManus, M.N., Borwick, C. and Crawley, E., 2020. Rapid systematic review: the impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry.

Lopes, B.C.D.S. and Jaspal, R., 2020. Understanding the mental health burden of COVID-19 in the United Kingdom. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy.

Mackey, A. and Gass, S.M., 2015. Second language research: Methodology and design. Abington: Routledge.

Mann, F.D., Krueger, R.F. and Vohs, K.D., 2020. Personal economic anxiety in response to COVID-19. Personality and Individual Differences, 167, p.110233.

Norris, J. M., Plonsky, L., Ross, S. J., & Schoonen, R., 2015. Guidelines for reporting quantitative methods and results in primary research. Language Learning, 65(2), 470-476.

ONS, 2020. Personal and economic well-being in Great Britain. London: Office for National Statistics. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing/bulletins/personalandeco nomicwellbeingintheuk/may2020 [Accessed 2nd March 2021]

Ons.gov.uk. 2021. Coronavirus (COVID-19) related deaths by occupation, England and Wales - Office for National Statistics. [online] Available at:

Pancani, L., Marinucci, M., Aureli, N. and Riva, P., 2020. Forced social isolation and mental health: A study on 1006 Italians under COVID-19 quarantine.

Panchal N, Kamal R, Orgera K, Cox C, Garfield R, Hamel L, Muñana C, and Chidambaram P., 2020. The Implications of COVID-19 for Mental Health and Substance Use: https://www. kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/the-implications-of-covid- 19-for-mental-health-and-substance-use/. [Accessed 2nd March 2021]

Pfefferbaum, B. and North, C.S., 2020. Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. New England Journal of Medicine, 383(6), pp.510-512.

Prasada, K.D.V., Vaidya, R.W. and Mangipudic, M.R., 2020. Effect of occupational stress and remote working on psychological well-being of employees: an empirical analysis during covid-19 pandemic concerning information technology industry in Hyderabad. Indian Journal of Commerce & Management Studies, 11, pp.1-13.

Qiu J, Shen B, Zhao M, Wang Z, Xie B, Xu Y, 2020. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations [published correction appears in Gen Psychiatr. 2020 Apr 27; 33(2):e100213corr1]. Gen Psychiatry. 33(2):e100213. Doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020- 100213 [Accessed 2nd March 2021].

Quigley, C. J., & Notarantonio, E. M., 2015. An exploratory investigation of perceptions of odd and even pricing. In Proceedings of the 1992 Academy of Marketing Science (AMS) Annual Conference (pp. 306-309). Springer, Cham.

Rahi, S., 2017. Research design and methods: A systematic review of research paradigms, sampling issues and instruments development. International Journal of Economics & Management Sciences, 6(2), pp.1-5.

Robb, C.E., de Jager, C.A., Ahmadi-Abhari, S., Giannakopoulou, P., Udeh-Momoh, C., McKeand, J., Price, G., Car, J., Majeed, A., Ward, H. and Middleton, L., 2020. Associations of social isolation with anxiety and depression during the early COVID-19 pandemic: a survey of older adults in London, UK. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11.

Rosenberg, M., Luetke, M., Hensel, D., Kianersi, S. and Herbenick, D., 2020. Depression and loneliness during COVID-19 restrictions in the United States, and their associations with frequency of social and sexual connections. MedRxiv.

Rossi R, Socci V, Pacitti F, et al., 2020. Mental health outcomes among front and second line health workers associated with the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. 1-5. doi:10.1101/2020.04.16.20067801

Sekaran, U. and Bougie, R., 2016. Research methods for business: A skill building approach. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

Smith, K., Ostinelli, E. and Cipriani, A., 2020. Covid-19 and mental health: a transformational opportunity to apply an evidence-based approach to clinical practice and research.

Smith, K., Ostinelli, E., Macdonald, O. and Cipriani, A., 2020. Covid-19 and telepsychiatry: development of evidence-based guidance for clinicians. JMIR mental health, 7(8), p.e21108.

Testa, M. A., & Simonson, D. C., 2017. The Use of Questionnaires and Surveys. In Clinical and Translational Science (pp. 207-226). Academic Press.

Tian, F., Li, H., Tian, S., Yang, J., Shao, J. and Tian, C., 2020. Psychological symptoms of ordinary Chinese citizens based on SCL-90 during the level I emergency response to COVID-19. Psychiatry research, 288, p.112992.

Uprichard, E., 2013. Sampling: Bridging probability and non-probability designs. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 16(1), pp.1-11.

Vindegaard, N. and Benros, M.E., 2020. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: Systematic review of the current evidence. Brain, behavior, and immunity, 89, pp.531-542.

Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, et al., 2020. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 17(5):1729. Doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729 [Accessed 2nd March 2021]

Wang, B., Liu, Y., Qian, J. and Parker, S.K., 2021. Achieving effective remote working during the COVID‐19 pandemic: A work design perspective. Applied psychology, 70(1), pp.16-59.

WHO, 2020. COVID-19 disrupting mental health services in most countries, WHO survey. [online] World Health Organization. Available at: https://www.who.int/news/item/05-10-2020-covid-19-disrupting-mental-health-services-in-most-countries-who-survey [Accessed 16 May 2021].

Wickens, C.M., McDonald, A.J., Elton-Marshall, T., Wells, S., Nigatu, Y.T., Jankowicz, D. and Hamilton, H.A., 2021. Loneliness in the COVID-19 pandemic: Associations with age, gender and their interaction. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 136, pp.103-108.

Williams, S.N., Armitage, C.J., Tampe, T. and Dienes, K., 2020. Public perceptions and experiences of social distancing and social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic: A UK-based focus group study. BMJ open, 10(7), p.e039334.

Wright, J., Steptoe, A., & Fancourt, D., 2020. How are adversities during COVID-19 affecting mental health? Differential associations for worries and experiences and implications for policy. MedRxiv Preprint. https:// doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.14.20101717 [Accessed 2nd March 2021]

Xu, X., & Banks, J., 2020. The mental health effects of the first two months of lockdown and social distancing during the Covid-19 pandemic in the UK. London: The IFS. https://doi.org/10.1920/wp.ifs.2020.1620 [Accessed 2nd March 2021]

Xue, B., & McMunn, A., 2020. Gender differences in the impact of the Covid-19 lockdown on unpaid care work and psychological distress in the UK [Preprint]. SocArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/wzu4t [Accessed 2nd March 2021]

Zhi., H. L., 2014. A comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. PubMed, 105-11.

Zhou, F., Yu, T., Du, R., Fan, G., Liu, Y., Liu, Z., Xiang, J., Wang, Y., Song, B., Gu, X. and Guan, L., 2020. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. The lancet, 395(10229), pp.1054-1062

Take a deeper dive into Challenges to Women's Empowerment in South Asia with our additional resources.

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts