Public-Private Partnerships in Infrastructure

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION

Introduction

Globally, the provision of infrastructure such as transportation, water, sewage, gas supply has been the customary responsibility of the respective governments. However, the lack of adequate public and private investment in infrastructure provisioning have been catalysed by population growth and unsustainable urbanisation (Gauba, 2017; African Development Bank, OECD & United Nations Development Programme, 2016). Presently, 55 % of the world’s population live in urban areas and by 2050, 68% of the world’s population is projected to be urban. Therefore, governments globally must develop strategies to improve provisioning of basic services, affordable housing and infrastructure to meet the requirements of the expanding global urban population (UNDESA, 2019). Public Private partnership ("Typical schools PPP stakeholders,") is the utilization of the resources of public authority and that of a private entity to provide a public service (Delmon, 2017).The primary objectives of PPP is the blending of public and private resources to achieve a goal or set of goals judged to be mutually beneficial for both of the private and the public entities ( . Jensen, 2016). Estache and Saussier (2014) have added that PPP projects help to free up government funds for other purposes. Similarly, Välilä (2020) argues that PPP projects provide improved efficiency in public service, innovation, value for money and transparency which ordinarily may hardly be achieved through traditional public procurement methods. Due to these advantages, the concept of PPP has been increasingly adopted globally to deliver infrastructure notably in developed nations such the United Kingdom, USA, Australia, China. For example, presently over 705 infrastructure projects are active in UK (HM Treasury, 2018b). In the USA, PWC (2016) reports that between 1985 and 2010; a total of 363 PPP projects have been recorded. Similarly, Commonwealth of Australia (2017) asserts that over 127 PPP projects have been recorded before 1980 across both social and economic infrastructure such as transport, education and utility sectors in Australia. Also, in China, PPPs accounted for 36 percent of the total infrastructure investment by 1997 (Chen & Doloi, 2008).There is also a growing trend in other developing countries such as India and South Africa. For example, PPP constituted 36% of its infrastructure expenditure while in its 12th development plan, it grew to 50% of its infrastructure investment amounting to about $ 8 billion. Presently, over 758 active PPP projects exist in India (Telang & Kutumbale, 2014) . Similarly, in South Africa, the budgetary provision of over $ 56 billion dollars for infrastructure provision from 2019 to 2022 shall be partly financed through PPP. It is estimated that PPP projects shall account for about $ 1.3 billion representing 2.2% of the projected infrastructure provision by the government(Oxford, 2019). Nigeria is fast becoming a global urban giant (Fox, Bloch, & Monroy, 2017). By the year 2050, it will become the third most urbanised country with 70% of its population living in urban areas and will account for 10% of the of the global population (UNDESA, 2015). The dynamics of urbanisation is a global phenomenon that will continue to reduce the average distance between cities and towns creating a diffusion of urbanisation towards rural areas (African Development Bank, OECD & United Nations Development Programme, 2016). Thereby, it would give rise to a huge demand for infrastructure and the need to upgrade existing services in order to support the economic activities of its growing population ( Guy, Marvin and Moss, 2016; Peterson, 2009). Moreover, the present effort by the government of Nigeria to deliver infrastructure through the traditional procurement route of direct funding have not yielded the required result. Presently, there are over 19,000 uncompleted or abandoned public projects (Umoru & Erunke,2016), which are estimated to gulp over $ 47 billion and would require an estimated 30 years to complete (Ewa, 2013). The situation of abandoned projects has become persistent in Nigeria due to various factors such as poor planning, incompetent project managers, incorrect cost estimates, poor design, political influence, poor funding, corruption etc. (Olalusi and Anthony 2012; Ubani and Ononuju 2013; Ayuba, et al. 2012; Hoe, 2013; Ayodele and Alabi 2011; Sharafadeen, Owolabi & Olukayode, 2018). This will remain so until strategies are put in place to address these issues through alternative means of funding infrastructure (Akinleye, 2017; World Economic Forum, 2018).

Nigeria has, in the recent past, adopted the concept of Public Private Partnerships (PPP) to bridge its infrastructure gap (African Development Bank OECD & United Nations Development Programme, 2016; Akintoye, et al., 2003). However, Nigeria has not recorded much success in PPP implementation due to challenges such as investments in infrastructure development projects which are not commercially feasible from the private sector perspective; the political and the non-commercial risks as well as poor organisational and regulatory capacities to monitor and provide an enabling environment for PPPs (Ahmed, 2011; Babatunde, 2015). However, Ogunsanmi (2014) argues that there was need to address concerns of stakeholders in PPP projects in Nigeria in order to improve project success. Owing to the renewed global interest in the adoption of PPP to bridge infrastructure gap, there has been a growing interest in the issues which make PPP successful in both practice and academia. Therefore, numerous researches have tried to ascertain the critical success factors (CSFs) of PPP projects in different countries (Toor and Ogunlana, 2008; Liu and Wilkinson, 2014; Osei-Kyei and Chan, 2017). A variety of CSFs have been inclined to stakeholder engagement (SE) (Eyiah-Botwe, Aigbavboa & Thwala, 2016). Chinyio and Akintoye (2008) confirmed the importance of SE in the modern forms of construction procurement such as partnering and the Private Finance Initiative (Lhuillery & Pfister) where many stakeholders are involved to ensure that the process could captures the varied stakeholder interests. Though, a variety of stakeholder engagement frameworks exist in construction industry (Bal, Fearon & Ochieng, 2013), very few are specifically tailored to the PPP projects. For example, El-Gohary, Osman and El-Diraby (2006) initiated the development of a SE model for PPP projects. However, Henjewele, Fewings and Rwelamila (2013) argued that it was complicated, limited to engaging stakeholders at the initiation stage and only considered the inputs of the government entity. Therefore, they initiated a framework which emphasized on integrating the ideas of the general public through the project lifecycle. Junxiao Liu, Love, Smith, Regan and Davis (2014) developed a framework using a performance prism, to measure CSF for performance of PPP stakeholder organisations through the project lifecycle. Similarly, based on PPP CSF, Babatunde (2015) developed a guide to help stakeholder organisations involved in PPP projects in achieving higher capability in Nigeria and developing countries. However, his insights on stakeholder engagement governance were also narrow. Casady, Eriksson, Levitt and Scott (2019) have added that standardized judicial and normative rules and procedures are required to govern the interaction between public and private actors. However, established protocols to appropriately engage stakeholder communities when considering PPP projects are also important but lacking in Nigeria (Akintoye & Kumaraswamy, 2017).

Problem Statement

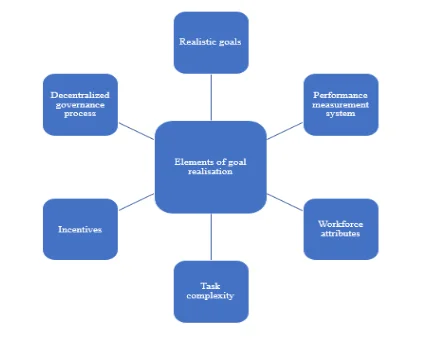

The primary aim of PPP projects is to deliver public governance via collaborative models, characterized by public and private sector cooperation (Andrews and Entwistle 2010). Grimsey and Lewis (2007) and Iossa and Martimort (2015) assert that goal realisation is the principal purpose of private financing as a governance tool in urban development, through investment in superior infrastructure asset development processes. The urban development process traditionally brings about an interplay of different stakeholders and policies that is plagued by potential risks of poor coordination including development of inaccurate targeting strategies, fostering of misconceptions and miscommunication and even the undermining of municipal and local capacity in the long term (Basedow ,Westrope & Meaux, 2017). Further, PPP projects in an urban setting are more challenging because PPP stakeholder organisation have varied institutional goals, norms and expectations which, make partnership between the public and private sector particularly challenging (Wojewnik-Filipkowska & Węgrzyn, 2019). The dearth of appropriate governance mechanisms which provide a platform for engagement through which the public interest can be protected despite the delegation of authority by governments to business concerns has become evident especially in developing economies and in immature PPP markets such as Nigeria (Baker, Justice and Skelcher 2009). Moreover, studies have shown that in Nigeria, a lack of clear coordination between the government, the concessionaire and the negligence towards fostering of public engagement hindered many projects at various stages of development, for example, the Lekki Epe concession toll road in Lagos state and the Abuja land swap project (Change, 2013; Gravito & Alli, 2017). The 2015 Infrascope evaluation of the environment for public private partnership in Africa ranked Nigeria 13th out of the 15 African countries despite its huge population and economic potentials (The Economist Intelligence Unit, 2017). The unfavourable PPP environment needs to be improved to attract the local and foreign investors and to ensure sustainability of existing projects. Furthermore, studies on PPP have grown tremendously in the last decades, but the gaps identified in the earlier studies are as the following:

Dig deeper into Dissertation Help Services Aid in Data Analysis with our selection of articles.

CSF studies in PPP have not critically analyzed engagement of the external stakeholders in the process of urban infrastructure provision.

Perceptions of stakeholders on CSFs for stakeholder engagement in PPP infrastructure projects have not been properly identified.

Studies have not looked at the key theories that impact the governance stakeholder PPP urban infrastructure projects.

Having identified these gaps, this research intends to develop a stakeholder engagement framework that can improve PPP project success in Nigeria. The framework will serve as guide that can foster engagement of PPP project stakeholders in an urban setting. The research shall attempt to answer the following questions:

How are urban infrastructure procured?

How are stakeholder engaged in PPP projects in Nigeria?

What are the critical success factors for stakeholder engagement in PPP urban infrastructure projects Nigeria?

What are the challenges of stakeholder engagement in Nigeria?

What are the key governance mechanisms which can improve stakeholder engagement in Nigeria?

Aims and Objectives

The aim of the research is to develop a strategy that can improve stakeholder engagement in public private partnership urban infrastructure projects in Nigeria. The objectives are:

To explore literature on PPP urban infrastructure delivery strategies.

To establish stakeholder engagement related challenges in PPP urban infrastructure Projects.

To Identify the critical success factors for stakeholder engagement in Nigeria.

To develop a stakeholder engagement framework for public private partnership in urban infrastructure projects in Nigeria.

To validate the developed framework of public private partnership.

1.3 Scope and Limitation of the Study

This study focuses on urban infrastructure projects procured through public private partnerships (PPP) infrastructure management in Nigeria. Throughout the world, PPP is increasingly adopted to deliver infrastructure. With the growing urbanization governments in Nigeria at different spheres are adopting PPP to bridge infrastructure. This research will focus on urban infrastructure that both economic and social in nature. Section 2.3 of the thesis elaborates on the different types of economic and social infrastructures.

Research Methodology Employed

The research objectives of research informed the choice of methods used in the study. A mixed method approach was employed to help answer the diverse and extensive range of the research questions relevant to the objectives, and to guarantee comprehensiveness of the research process. The table below illustrates the research design adopted. The research will be carried out in 3 phases. The methods used were literature review; questionnaire-based surveys; qualitative interviews; and evidence from documentary sources; The Table below maps out the summary of the research flow. The first phase involves critical literature review while in the second phase both literature review while in the second phase, it involves collection of primary and secondary data from the field. In the final phase of the research, the theoretical framework is validated using focus groups. Chapter 5 of the thesis clearly elaborates the research process

Research Structure

To achieve the research flow as indicated in the table above, the thesis shall be structured into nine chapters as briefly detailed below:

Chapter One: It introduces the subject of the thesis, Problem statement justification of research, research question, aims and objectives of the thesis.

Chapter Two: The chapter will provide an overview of the literature on Urban Infrastructure delivery. The methods of providing urban infrastructure. It also discusses public private partnership experiences in other countries and Nigeria as a strategy for infrastructure provision

Chapter Three: This chapter will describe the importance of stakeholder engagement, tools, and techniques and Key principles of engagement and barriers to stakeholder engagement.

Chapter Four: It reviews theories which underpin stakeholder engagement in public private partnership urban infrastructure projects. It attempts to develop a conceptual framework that will guide the research analysis.

Chapter Five: This chapter will describe in detail the research methodology that has been applied in undertaking this research. The chapter would also explain the steps followed and methods employed by the researcher for the purpose of data collection.

Chapter Six: This chapter will focus on detail analysis of the collected data from the face-to-face semi-structured interviews and discussion of the qualitative results of the survey to understand stakeholder perception on the practice of stakeholder engagement in the research context.

Chapter Seven: This chapter will focus on detail analysis of the collected data from questionnaire and discussion of the quantitative results of the survey on critical success factors of stakeholder engagement in the research context.

Chapter Eight: This chapter will focus on development of a conceptual framework for stakeholder engagement readiness assessment of stakeholder organisation. It shall also validate and test the framework detail analysis of the collected data from questionnaire and discussion of the quantitative results of the survey and focuses on issues relevant to shared Goals in the research context

Chapter Nine: This chapter will lay emphasis on discussions of findings and recommendation for future research.

1.4 Contribution to knowledge

I. Theoretical contribution – Development of a theoretical analytical framework using multiple theories to help address issues relevant to stakeholder engagement in PPP projects.

II. Practical contribution – Development of a stakeholder engagement framework that can improve the practice of stakeholder engagement in PPP urban infrastructure projects.

Chapter summary

This chapter gave a background of the research, aims and objectives of the research. It also outlined the research process and suggested the research methodology to be adopted for the study.

CHAPTER 2: LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Introduction

This chapter discusses urbanisation and urban infrastructure delivery strategies. It also highlights the concept of public private partnerships as a procurement strategy of infrastructure.

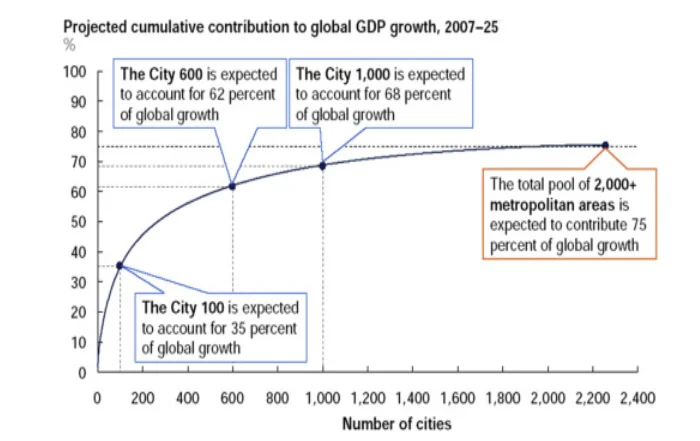

2.2 Urbanisation

Urbanization is a fundamental phenomenon of multidimensional transformation which rural societies go through in order to evolve into modernized societies from sparsely populated areas to densely concentrated urban cities (Oni-Jimoh, Liyanage, Oyebanji, & Gerges, 2018). The word ‘urbanisation’ is often used as a catch-all term to represent urbanisation, urban growth and urban expansion (Fox and Bell, 2016; Fox and Goodfellow, 2017).The term ‘urbanisation’ is used here to refer specifically to an increase in the proportion of a country or region’s population that resides in urban settlements, while ‘urban growth’ refers to an increase in the absolute size of a country or a region’s urban population. These terms are frequently used interchangeably in both academic and policy circles (Fox, 2012; Potts, 2012).Urban means town or city and refers to both built-up agglomerations and the way of life (Antrop, 2000). Since the 1930s, Urban areas have been created and further developed by the process of urbanization (Park & Burgess, 2019). Presently, 55 % of the world’s population live in urban areas and by 2050, 68% of the world’s population is projected to be urban. Therefore, governments globally must develop strategies to improve provision of basic services, affordable housing and infrastructure to meet expanding populations need (UNDESA, 2019).The dynamics of urbanisation is a global phenomenon that will continue to reduce the average distance between cities and towns creating a diffusion of urbanisation towards rural areas (African Development Bank, OECD & United Nations Development Programme, 2016). This trend creates a continuum of towns that make it difficult to separate what is rural and urban (Potts, 2012) and affects all facets of community development, ushering changes in the physical, demographic, economic, and social characteristics (Cobbinah, Erdiaw-Kwasie, & Amoateng, 2015b). It can be said that urbanisation is a product of social, economic and demographic evolution that concentrate population in large towns and cities changing land cover/use, social lifestyle and relations and economic structure. Urban areas provide far more economic growth than rural areas. As illustrated in figure 1 bellow, presently, over seventy five percent of the global GDP is generated in over two thousand Cities. Whereas six hundred cities account sixty percent of global GDP out of which thirty five percent are accounted for by 100 cities.

However, urbanisation can either stimulate or impede growth and development of urban areas in both developed and developing countries if not harnessed properly (Cobbinah, Erdiaw-Kwasie, & Amoateng, 2015a). In the developed world, urbanisation is historically linked to economic growth (Henderson, Roberts, & Storeygard, 2013). However, since the end of the Second World War, developing countries are increasingly becoming urbanised (Glaeser, 2014; Glaeser and Henderson, 2017). Such countries include Bangladesh, Pakistan, Kenya, Nigeria, and Philippines which are presently fast becoming urbanised with some of their cities having up to 11 million inhabitants. The prevalence of poor mega-cities today runs counter to historical experience. In the past, the world’s largest cities were almost all in the most advanced economies (Jedwab & Vollrath, 2019). Excess urbanization beyond the appropriate speed for economy and society to adjust causes various problems. These internal urban issues offset a part of urban productivity gains which are worst indices for the poor in urban areas. Thus, living environment for the urban poor is further worsened, and the informal economy which is characterized by expansion of economic activities not captured by formal statistics and not covered by social security and regulation are severely affected (Iimi, 2005). Conflating these issues is analytically problematic and can lead to confusion about what is happening, and, by extension, what the appropriate policy responses might be (Fox, 2014; Fox and Bell, 2016; Fox and Goodfellow, 2016). In the recent past there has been renewed emphasis on the role of infrastructure as a driver for poverty reduction and competitive advantage of urban areas(Prud’Homme, 2005). How cities prevent the negative impact of urbanisation depends on policies and enabling environment that are put in place (Cadena, Dobbs et al. 2012).

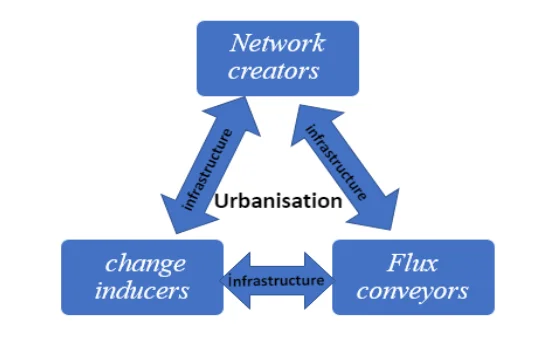

2.2.1 Relationship between Urbanisation, Infrastructure and Sustainable Development

The World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) identified sustainable development as that which ``meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs'' (WCED, 1987, page 43). A common understanding of the term in policy is linking economic, social, and environmental concerns to form the so-called `triple bottom line' (Pope et al, 2004). The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) based policy has reiterated that provisioning of adequate infrastructure is key to actualising SDGs and empowering societies globally(Aizawa, 2020). Urbanisation has diverse impact on each society’s historic, economic, environmental, structural and cultural background (Brakman, Garretsen, & van Marrewijk, 2015; Concepción, Moretti, Altermatt, Nobis, & Obrist, 2015; J. D. Miller & Hutchins, 2017; Yach, Mathews, & Buch, 1990). As illustrated in Figure 2, the phenomenon is associated with increased concentration; movement of people within the greater urban areas; changing physical environments increase the need for employment and education socio-cultural changes healthcare needs, housing and transportation. Infrastructure is fundamental in an urban setting because it aids network creation, flux conveyance and induces change in urban areas. The key determinant for the support for sustainable urbanisation is infrastructure. Numerous authors confirmed that infrastructure transforms human settlements from loci of small city-states reminiscent of ancient Greece into the definitive centres of economic and cultural production and reproduction of the new millennium (Bilgili, Koçak, Bulut, & Kuloğlu, 2017; Lin & Du, 2015; Neuman & Hull, 2009). In urban areas, infrastructure matters first because it provides crucial final consumption items to households, particularly water and to a lesser extent energy and telecommunications. In addition to its impact on the aggregate income, infrastructure can also have an impact on income inequality and this issue has attracted increasing theoretical and empirical attention in recent years.

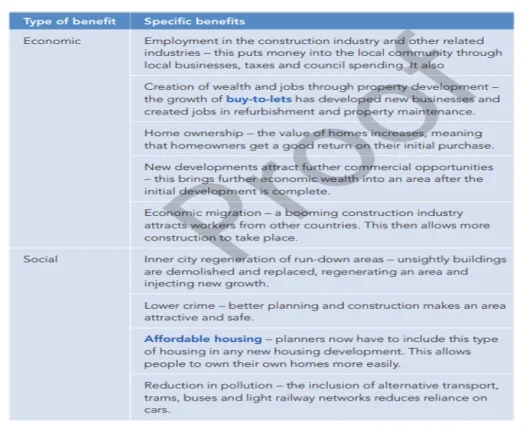

Conceptually, there are good reasons why infrastructure development may have a differential effect on the incomes of the poor, over and above its impact on aggregate income (Cobbinah et al., 2015a). Infrastructure facilitates the poor’s access to productive opportunities, raising the value of their assets. It can also improve their health and education outcomes, thus enhancing their human capital. More broadly, access to and use of infrastructure services including telecommunications, electricity, roads, safe water and sanitation play a key role in the integration of individuals and households into social and economic life (Hashmi, Ishak, & Hassan, 2018; Lloyd-Jones & Rakodi, 2014; Maria, Acero, Aguilera, & Lozano, 2017; Misra, 2019; Palei, 2015). Infrastructure planning can support growth and liveability by refocusing the frame of decision-making to the broader socio-technical system in which physical infrastructure systems are embedded. The uncertainty of urban growth implies that investment decisions may consider alternative interventions with lower requirements for physical capital expansion (McArthur, 2017b). In order to nurture a competitive environment for a service economy in urban areas, the development of infrastructure systems are required, even at the feeder level, as a means of enabling efficient distribution of public value in urban areas (Iimi, 2005). For small and medium industries, especially in developing countries, about half of infrastructure services constitute intermediate consumption for small firms and therefore, the measure of availability of the infrastructure services impacts on their business sustenance. Straub, (2008) asserts that small firms rely on the existence of a suitable and relatively cheap transport and telecommunication network to provide service to existing clients and network with associates and even penetrate new clients. In addition, significant portion of urban infrastructure services are utilised as final consumption by households. Therefore, it impacts on a significant portion of expenditure of urban dwellers especially the poor in developing countries. Foster and Yepes (2005) have shown that households in developing countries spend a significant fraction of their income on water and electricity. For example, in a sample of Latin American countries, households in the poorest quintile often spend more than 5% of their income on water and more than 7% on electricity. Therefore, its availability and affordability are important for sustainable livelihoods in cities. As illustrated in table Table 2 bellow, the value generated from infrastructure arises not just as a facilitator of economic activities but as the provider of the employment in the process of construction and also, it provides employment in the accompanying regulatory and operating services, thereby fostering economic and social benefits (Cobbinah et al., 2015a; McArthur, 2017a).

Therefore, infrastructure is increasingly been utilised as an economic stimulus tool deployed to revamp failing economies. During the global financial meltdown from 2007 to2008, both developed and developing countries invested about 40% of their stimulus into infrastructure funding while advanced economies spent 21% (International Labour Organization 2011). A number of researches have confirmed the causality between expansionary infrastructure policies with improvement of economic performance of the country (Lorde, Waithe, & Francis, 2010; Odhiambo, 2010; Sami, 2011; Shahbaz, Mutascu, & Tiwari, 2012; Solarin & Shahbaz, 2013). In the Scottish construction sector for example, the indirect impact of core construction has a multiplier of 1.6, it is evaluated that each £1 spent on construction generates a total of £2.84 in total of economic activity (Scottish Parliament, 2019). In the European Union, the process of infrastructure provision provides about 18 million direct jobs and contributes to about 9% of the EU's GDP (European Commission, 2019). Therefore, if the lack of infrastructure or low quality infrastructure are key constraints on development and economic activities, then, an increased expenditure on infrastructure may ultimately stimulate innovation as well as economic and social benefits (Agénor, 2010). However, the optimal level of infrastructure required by a society is an issue of contention. Though Samuelson (1954), posits that the level of infrastructure capital for a society is ideal when supplementary infrastructure delivered through private sector efforts shrinks social utility. However, marginal benefits i.e. economic and social benefits, surpass marginal infrastructure expenditure when provided in surplus and can consequently lead to subsidising the cost of doing business within a society and, thereby, diffusing economic advantages to less viable businesses, consequently, increasing their chances of prospering. On the contrary, infrastructure deficit stifles the enabling services and networks required to aid a functional economy, leading to economic failure (Samuelson, 1954). In addition, with a poor infrastructure endowment, the marginal productivity of existing infrastructure will be low and alow-growth equilibrium may be attainable only by the economy; however, a substantial level of infrastructure network expansion would raise the productivity in the society and permit reaching the high-growth equilibrium (Agenor, 2013). Banyte (2008) also analyses infrastructure as the factor that determines successful diffusion and adoption of innovation in the market. However, infrastructure shortages have become increasingly serious as a result of the growing population and the modernization of the global economy, especially in developing countries such as Nigeria (Wang, Kwan et al. 2019). It can be said, that, infrastructure is fundamental to production and other economic activities. It also supports the wellbeing and comfort of the inhabitants of an area. It helps to diffuse economic benefit to the poor. Similarly, it improves competitiveness of cities and improves its internally generated revenue due to flourishing economic activities. The following part of the thesis will investigate the definition of infrastructure, the types and delivery strategies.

2.3 Urban Infrastructure

Urban infrastructure comprises of a socio-technical system of facilities and services, such as power supply, the Internet, telephone services, pipe borne water, refuse collection, health and education facilities and housing and others, which are important to the basic operation of towns and districts (Dong et al., 2018). They consists of capital goods which are not consumed directly; they provide services only in combination with labour and other inputs (Prud’Homme, 2005). They share some common characteristics; they have a high fixed cost, long economic life, the potential to dominate a market and to interact with other infrastructure projects (Office for National Statistics, 2017). Infrastructure is the physical network that channels a flux (water, fluid, electricity, energy, material, people, digital signal, analogue signal, etc.) through conduits (tubes, pipes, canals, channels, roads, rails, wires, cables, fibers, lines, etc.) or a medium (air, water) with the purpose of supporting a human population, usually located in a settlement, for the general or common good. It consists of a long-lasting network connecting producers and service providers with a large number of users through standardized (while variable) technologies, pricing and controls which are planned and managed by coordinating organizations (Neuman & Hull, 2009). In economic terms, however, infrastructure can be a structure which allows for the production and exchange of goods and services. Broadly defined, the concept of infrastructure is not limited to public utilities, but may also refer to information technology, informal and formal channels of communication, software development tools and political and social networks which support the economic system (such as a city or a country). It also encompasses the soft aspects of infrastructure such as operating procedures, management practices and development policies that interact with societal demand and the physical world to facilitate the transport of people and goods and the provision of safe water and energy, among others (Bhattacharyay, 2009; Yumi, 2017).

2.3.1 Categorisation of Urban Infrastructure

Infrastructure could be categorised as economic or social. An economic infrastructure includes transportation, electricity, communication and water and other services or the systems that are important for the economic activity of people. On the other hand, social infrastructure includes housing, educational and health services and other services and systems which are socially inclined (Infrastructure and Projects Authority, 2016). Frank and Martinez-Vazquez (2014) suggest that infrastructure can be classified as a network or point. They note that a ‘network infrastructure’ includes roads, bridge telecommunications, energy infrastructure and so forth, while a ‘point infrastructure’ includes health facilities and educational facilities and so on, which is more common to the social sector and requires human capital to provide optimal services to its citizens, such as instructors and medical practitioners. As illustrated in table 3, Buhr (2003) identified infrastructure based on human wants such as water, warmth, light, health, shelter, security, information, education and mobility.

Torrisi (2009) has argued that, the priorities for infrastructure need depend on the region of the world and the requirements of their citizens. For example, in less developed countries, many attach more importance to a basic infrastructure, such as water and irrigation, while in developing countries the demand for transport and social infrastructure is greater. Similarly, in highly developed countries, electricity and ICT are of greater significance. However, Buhr (2003) has outlined that to achieve the optimal outcomes from infrastructure provisioning three crucial tactics are required to be applied. Firstly, it should serve as medium for economic diffusion i.e. the economic process through provision of mechanisms that can support entrepreneurship, skilled and unskilled labour opportunities, capacity building etc. Secondly serve as a medium for satisfying long and short-term educational requirements. Thirdly, it should serve as medium that fosters social interaction. Therefore, policymakers must select or encourage the procurement of an appropriate form of infrastructure that suits the present stage of a country’s development and context and also embed appropriate mechanisms that will ensure citizens get value for money (Lee, 2015; National Infrastructure Commission, 2017; Perkins et al., 2005).

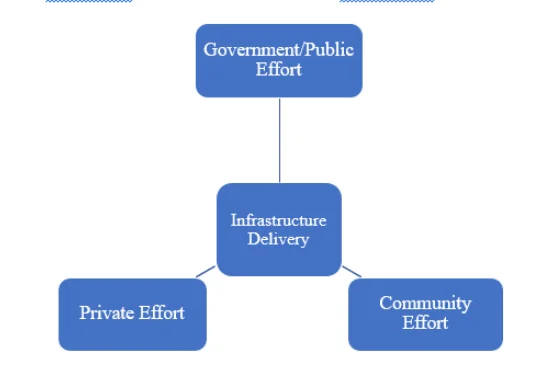

2.3.2 Urban Infrastructure procurement Systems

Masterman (1995) refers to phrases such as ‘building procurement method’, ‘procurement form’ and procurement path’, which have been used by various authorities when referring to this concept acquiring an infrastructure. According to Franks (1984), procurement system is combination of activities undertaken by a client to obtain an infrastructure. Rwelamila (2000) views it as organizational structure adopted by the client for the management of the design and construction of an infrastructure project. However, Adjei (2016) & Rahmani (2017) suggest that procurement system is the set of agreements prepared to guide the execution of an infrastructure project which must enable the client to meet the objectives set to be realised upon completion of the project. McDermott (1999) adds that procurement system must foster improved technology adoption and process and provide a platform for learning and skill development. A variety of procurement systems exist with different arrangements which differ in terms of how responsibility is apportioned, the sequential order of activity, processes and procedures and, finally the organizational approach in project delivery (Ali et al, 201). The variances in procurement systems impact on project delivery performance (Tang, 2019). Infrastructure could be delivered through community effort, private effort or by the government (see figure). From this point onwards, infrastructure has been delivered through community efforts where a group of persons with a common interest deliver infrastructure to serve their common good. Similarly, there were private endeavours by business interests to deliver infrastructure for economic gains. However, the community efforts lacked sustained efforts and the quality of the infrastructure delivered remained poor and inadequate (Akin, 2016; Mansuri & and Rao, 2004). On the other hand, the private efforts were more profit oriented and where provided, they had high potentials for segregation and unaffordability to some segments of the society (Trangkanont & and Charoenngam, 2014). The essence of government is to cater for the welfare of its citizen (Wilson, 2017), therefore government participation in infrastructure provision remains the most viable form of infrastructure delivery strategy in order to deliver welfare to all its citizens. The following part of the thesis shall discuss on infrastructure procurement strategies adopted by government to deliver infrastructure.

3.3.3 Public Infrastructure procurement system

The procurement of infrastructure by government has been majorly through conventional methods until after the Second World War (1939–1945) (J. B. Miller, 2013). According to Kwakye (2014), the conventional system saw the separation of design from construction and each stage of the production process managed separately. This procurement method may be characterized as a sequential approach: conception, development and implementation phases are each completed and approved before proceeding to the next as has been demonstrated in Figure 2.2 below.

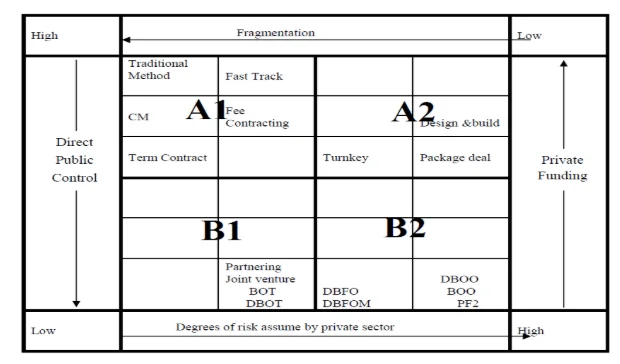

Following that era, numerous procurement systems have emerged. The growing adoption of these procurement systems were basically as result of decimal performance of the traditional procurement types (Pietroforte & Miller, 2002). The second phase was a time of economic decline which saw the gradual shift from traditional to non-traditional procurement systems. The third phase was ushered in by the global economic recovery which saw experienced clients adopting the design and build and management-orientated systems. In the fourth phase, new systems emerged which had been hybrid of both traditional and modern construction procurement systems(Pietroforte & Miller, 2002). Masterman (2002) have categorised the main procurement systems into four different segments such as, the separated procurement system, the integrated procurement system, the management oriented procurement system and the discretionary procurement system. In an earlier contribution, Miller 1995 asserts that procurement systems can be classified according to two dimensions: the type of project delivery and the choice of project finance method (see Figure 1).The vertical axis represents a continuum in which funding responsibilities (i.e. financial risks) for producing, operating and maintaining a facility are shifted from government (direct funding) to private investors (indirect funding). The horizontal axis, instead, represents the extent according to which the various phases of a facility lifecycle are procured separately (segmented procurement) or combined with each other (combined procurement). These two axes form four quadrants according to which different types of project delivery systems are classified (Pietroforte & Miller, 2002). Howes & Robinson (2005) also presented an infrastructure procurement framework made up of four categories (see Figure 2.4) which was delineated into four namely: A1; A2; B1 and B2 quadrants. Within the A1 quadrant the procurement systems, projects are fully funded by governments or public entities with thegovernments having the dormant control over the project. This category comprises traditional method; design and build; fast track; fee contracting; construction management and term contract. On the A2 quadrant, procurement systems which fall within this category such as design and build, packaged deals and turnkeys are characterised with government control. However responsibility for design and construction lies with a single organisation (Masterman 2002; Howes & Robinson, 2005;(Pietroforte & Miller, 2002). However, in the B1 quadrant, procurement, systems are characterised by reduced government control and risk burden. Procurement systems within this quadrant include build-operate-transfer (BOT); partnering; design build operate and transfer (DBOT) and joint ventures. Whereas in the B2 quadrant, procurement systems are characterised by divestiture of risk and financial responsibilities from government to the private sector (Delmon, 2010). These procurement systems include design-build-own-operate (DBOO); design build-finance-operate-manage (DBFOM); build-own operate (BOO); private finance 2 (PF2) and design-build-finance-operate (DBFO) models(Howes & Robinson, 2005 Delmon, 2010).

The Latham report revealed that traditional construction strategies were adversarial and there was need for adoption of more innovative procurement strategies. In this regard, collaborative construction project arrangements have been the subject of many development efforts owing to the frustration felt towards the challenges such as funding and opportunism and conflicts inherent in traditional procurement system. Globally, three approaches have stood out: project partnering, project alliancing and integrated project delivery which are also referred to as public private partnerships (Lahdenperä, 2012). The following part of this study shall focus on PPP procurement strategy which falls within the B1 and B2 quadrant as illustrated in figure above.

2.4 Public Private Partnership PPP

Public Private partnership (PPP) is the utilization of the resources of public authority and that of a private entity to provide a public service (Delmon, 2017). It involves risk sharing through design of hybrid organizations and contracting out management and provision of government business to private entities (Schelcher, 2005). It as a relationship in which public and private resources are blended to achieve a goal or set of goals judged to be mutually beneficial both to the private entity and to the public (J. Jensen, 2016). The goal of PPP infrastructure delivery is due to the need to bridge financial and managerial capability in both centralised and decentralised infrastructures (Davoodi and Tanzi, 2002). It has fast been adopted by politicians as a mechanism to quickly meet up political promises due to short time horizon of their political mandate (Bahl and Bird, 2013). The modern PPP focus for public infrastructure began in Australia and the United Kingdom in the 1990’s (Hodge, Greve and Boardman, 2017). For example, in Australia, notable urban infrastructure projects financed through PPP include the City Link Project in Melbourne and Sydney's Cross City Tunnel and in the United Kingdom the Thames crossing and the London underground expansion have been financed through PPP .Both countries have also used PPP finance projects in health, education and prison among others (Vries and Yehoue, 2013; Jefferies and Rowlinson, 2016). Similarly, in Europe America, Canada and China, the adoption of PPP is on the rise (Hodge, Greve & Boardman, 2017; Long & Wang 2016). In the developing world, success stories of the adoption of PPP in countries such Malaysia, India and South Africa and Nigeria have come forth in the area of urban infrastructure provision such health, housing and transportation services (Walwyn & Nkolele, 2018 Tsukada, 2015; Ismail & Harris, 2014; Yang, Hou &Wang 2013). However, some scholars have argued that there is a growing trend of infrastructure provision through PPP beyond the need to bridge capability and finance, it is a quick way to fulfil the political promises due to short time horizon of their political mandate (Bahl and Bird, 2013; Osei-Kyei and Chan, 2015). It can be associated with opportunism, lengthy procurement process and high transaction cost (Thomassen et al., 2016; Liu and Wilkinson, 2014).

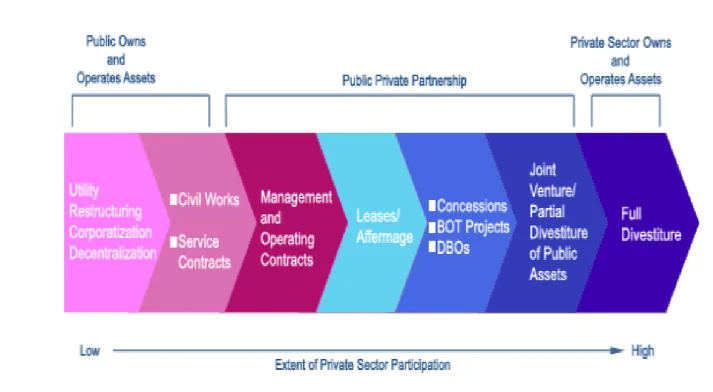

2.4.1 Forms of PPP

PPPs are of various forms can vary by degree of private participation see figure 2 The development and form of PPP vary by country ((Delmon, 2010, 2017).

Design & Build (Das Gupta et al.): DB is an integrated method of project delivery that combines design and construction services into one contract with the private entity as single point of responsibility (Q. Chen, Jin, Xia, Wu, & Skitmore, 2016). The option has some merits over the traditional contract but could pose some risks at the operational phase for the government partner and hence, it may not provide full value “value for money” (Ramsey, El Asmar, & Gibson, 2016).

Private finance initiative (Lhuillery & Pfister): A typical PFI project involves the setting up of a consortium of stakeholders to finance, build operate an infrastructure. As practised in the UK since 1992, the government pays for services rendered to the public on its behalf or user fees are charged by the consortium to recoup its investment (Khaderi & Shukor, 2016).

Design, Build and Operate (DBO): It is the integration of designing a, constructing and operation of an infrastructure in a single contract (Merna & Njiru, 2002). The financing usually comes from the public sector arm of government and the owner ship of asset is retained by public sector whereas, the obligation for the building of infrastructure and its operation through a defined period is the responsibility of the private partner (Merna and Njiru, 2002). Upon the expiration of the contract period, the contract could be renewed or the facility is returned to the public sector (Federal Transit Administration, 1999; Zhang & Kumaraswamy, 2001)

Operational Contracts (O&M): These types of contracts usually span beyond twenty years upon which the facility is returned to the public entity (Tsang, 2002). An existing public infrastructure is given as concession to a private entity and he runs and maintains infrastructure which could sometimes include upgrading or refurbishment (Lai & Yik, 2007).

Design, Build, Finance and Operate (DBFO): The private entity has the contractual obligation for designing, building, financing and operation of the infrastructure. The private partners investment is recovered through user pay fees (McArthur & Sun, 2015).

Build, Own, and Operate (BOO): The private entity independently builds, owns and operates the facility. There is usually a form of leverage given to the private entity to ease the realization of the project. In this form of partnership there is no direct financial contribution from the public entity however there could be leverages such as tax exemption (Bernstein, Gonzalez, & Heikal, 2016).

Private Finance Initiative - The Term Private Finance Initiative (Lhuillery & Pfister) has been defined as a subset of PPP (Quiggin 2004; Li et al,2005; Singaravelloo 2010). The PFI model evolved to become one of the most commonly applied collaborative frameworks amongst national and regional governments around the world. The framework covers a wide spectrum of private sector participation, including management contracts, lease contracts, concessions, and divestiture/privatisation (Ball and Maginn, 2005; HM Treasury 2009). The UK is a leading and typical example of a developed country where the dominant PFI model has been extensively used to manage infrastructure since 1992. Other countries which have adopted this approach include Australia, Canada, Finland, France, Ireland, Japan, Malaysia, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, the United States and Singapore (RICS, 2011). PFI is a legal framework for managing concession projects in the United Kingdom, in which the government (public sector) buys and regulates the services of the private sector in providing public infrastructure (Li and Akintoye 2003). The goal of this framework is to increase the use of private sectors‟ money and management skills in procuring public projects at both central and local authority levels. In effect, the private sector earns more business profit on investment (Akintoye and Beck 2009). Under PFI procurement, the government does not partake in infrastructure construction, as an alternative it purchases service from the private entity for what it uses or in addition a minimum guaranteed purchase of service such as schools, roads, hospital builds prisons etc (Akbiyikli & Eaton, 2006).

Divestiture: Under this model, the government agrees for the private entities to take ownership of an existing infrastructure facility or build a new one. The private entity will have control over all the asset, maintenance and operations. However, the government takes regulatory oversight to ensure that end user charges and service standards are within agreed standards and threshold (Choudhary, Singh, & Gupta, 2019; Kirkpatrick, Parker, & Zhang, 2004). They can come in a variety of structures, for example, Regulatory Asset Base (RAB) partnership where a tariff plan is agreed upon over a long period of time between the government and the service provider. It is aimed primarily at encouraging investment in the development and upgrading of infrastructure (Davis, 2019). The licence to operate and tariff is set by an autonomous regulator who ensures that services and expenditures are in the interest of the users. It is a type of economic regulation typically used in the UK for monopoly infrastructure assets such as water, gas and electricity networks. In 2016, the model was applied successfully for the first time to a single asset construction project of the £4.2bn Thames Tideway Tunnel (TTT) sewerage project (Department of Business Energy & Industrial Strategy, 2019).

The procurement systems which fall within this quadrant are characterised by varying structural complexities and merits. contrary to the conventional wisdom, infrastructure investments do not typically lead to economic growth (may be in the short run) especially if it fails to capture stakeholder expectations (Ansar, Flyvbjerg, Budzier, & Lunn, 2016). Therefore, the decision to embark on an infrastructure development project and the choice of procurement system should be hinged on the needs of stakeholders in the infrastructure project or the program to be formulated on a country-by-country, sector-by sector and project-by-project basis (Carbonara, Costantino, & Pellegrino, 2016; Delmon, 2010).

2.4.2 Global experiences and challenges of PPP

There has been a rise in the adoption of PPPs as procurement system for infrastructure by governments globally (Li et al., 2005a; Leininger, 2006; RICS Policy Report, 2012). It has been reported that about 135 countries now adopt the procurement system as a strategy to build new infrastructure or improve existing stock with an investment magnitude in excess $158 billion globally (World Bank Group, 2016b). The major countries known to have established PPP as a procurement strategy for infrastructure include UK, USA, Canada, Spain, South Africa (Eggers & Startup, 2006). However, most recently, the top five countries with PPP infrastructure investment commitments have been consisted of Argentina, Brazil, China, India, and Mexico (World Bank Group, 2018). It is essential to elucidate summarily the PPPs environment and challenges in some of the countries mentioned earlier. The focus of this study is on stakeholder engagement hence it will focus on stakeholder elated challenges as follows:

UK experience

UK economy has matured through having adopted the strategy to deliver infrastructure and public service through the PFI initiative. Presently about PPP projects are in existence valued at over 705 capital value of £56.6 billion are active (HM Treasury, 2018b). The UK government has incurred an average of £10 billion pound charges towards PFI projects between 2016-2017 representing 0.5% of its GDP and still has an obligation based on existing contracts to pay about £ 200 billion from now till over 2040 (Wolf, 2018). Following the relative successes of PFI in UK, numerous countries are beginning to adopt the strategy to procure infrastructure projects (Khaderi & Shukor, 2016). However, the adoption of PPP to deliver infrastructure has slowed down in recent years. For example 86% of PFI and PF2 contracts were signed before 2010 (House of Commons, 2018). However, due to stakeholder concerns, the government has halted the adoption of PFI strategies for new projects since 2018, however, it will continue to meet obligations of existing contracts through there Lifecyle. However, other forms include successful and established tools relevant to PPP such as Contracts for Difference, the Regulated Asset Base Model and the UK Guarantee Scheme in recent time (Davis, 2019; HM Treasury, 2018a).In the recent past , the government in UK have been unable to meet up to certain PPP obligation. For example, the ‘priority school program has required £1.7 billion for the Future Force 2020 scheme for military accommodation and the rolling stock for the Crossrail project and each has a financial shortfall of £1.2 billion that |UK governments have been unable to pay its private partners. (The Economist, 9 March 2013, 30–32). A report published by the Public Accounts Committee of the House of Commons, stated that returns to investors have been too high and had led to massive high financial liabilities to public authorities. The report concluded that it could not identify the value for money realised in a lot of PPP projects in UK (Willems & Van Dooren, 2016). There are also evidences of poor management of stakeholder relationships as contributory cause of poor performance of PPP projects in the UK (Smyth & Edkins, 2007)

United States (USA) Experience

PPPs have been adopted in USA from hitherto now. For instance, as early as 1792, the first long-distance stone and gravel road in the country was delivered in Lancaster Turnpike and the intercontinental rail road in 1869 (Smith, 2009). There is no standard approach to delivery of PPP in the USA as opposed to the UK where the standardised approach is the PFI strategy. In addition, USA operates a decentralised management system. Authority to undertake PPPs is typically granted to agencies by the Congress on an agency-specific basis or even on function-specific or project-specific basis (Smith, 2009).Therefore, capturing the total number of PPP projects in USA is difficult. However, PWC (2016) reports that between 1985 and 2010; a total of 363 PPP projects have been recorded, with a total value of US$59.5 billion P3s in the US being represented by toll road concessions. However, the governments and investors are now coming together on a much broader range of projects, including social infrastructure. However, in consideration of the size of the US economy which is six times bigger than the UK economy, it can be said that the full potential of PPP is yet to be utilised to deliver infrastructure in the USA. Presently, much is expected from the PPP market in the US, where the economy is more than six times bigger than the UK economy. There are indications that PPP is witnessing a growth in USA, for example, in 2015, five deals were closed while in 2016, nine deals were closed (InfraDeals, 2015; PWC, 2016). However, some projects have witnessed. The slow maturity of PPP-enabling institutions, legal frameworks, and governance structures is having an effect on America’s PPP growth (Casady & Geddes, 2019). Similarly the laws do not offer adequate incentives, transparency, and accountability for the U.S. to successfully deliver a coordinated PPP program (Geddes & Reeves, 2017; Reeves, Palcic, Flannery, & Geddes, 2017). In certain projects have experienced challenges of devious conduct by key stakeholders and the transaction costs were also huge for example, California freeway SR 91 Express Lanes which had been opened in 1995. Though many highway projects are relatively predictable from a construction cost perspective, these are highly uncertain from a utilitarian perspective. For example, there was relatively little problem in constructing the Dulles highway on schedule. However, use levels on the toll road were significantly lower than anticipated (10,000 per day during the initial month versus 34,000 per day projected) (Vining, Boardman & Poschmann, 2005). PPP in USA also suffer from poor management of stakeholder relationships which is a contributory has been found to be a contributory cause of failure of PPP projects (El-Gohary et al., 2006).

Australian Experience

Australia is considered as one of the most mature PPP markets globally amongst other countries with a strong focus on value for money but operates a rigid PPP framework with few PPP models in operation and thus decreasing its potential for more PPP projects. (Utz, 2013). However, English (2006) asserts that over 127 PPP projects have been recorded before the end of 2005, with a total value of AU$35.6 billion spread across both social and economic infrastructure in the transport, education and utility sectors. According to Infrastructure Partnerships Australia (2019) road and social infrastructure are the most common types of infrastructure delivered through PPP followed by renewable energy generation, passenger rail and water infrastructure (Infrastructure Partnerships Australia, 2019). However, despite its experience and expertise, Australia is still experiencing challenges in implementing some of its PPP infrastructure projects. The ‘East West Link’ is a large PPP infrastructure project that was recently terminated (VAGO, 2015). Similarly the ‘Sydney Light Rail’ project is also experiencing both technical and non-technical challenges (Casimir & McDougall, 2018). The key challenges affecting Australian PPP projects are inclined to skills of key stakeholders, huge cost burden on the public, poor public accountability, efficiency of the Treasury office and balancing competing interests within public agencies which limit decision making within the guidelines which govern PPP in Australia (Mwakabole, Gurmu, & Tivendale, 2019).

Chinese Experience

China is increasingly adopting PPP to deliver infrastructure especially with the wave of urbanisation. Based on 2017 evaluations, over fourteen thousand projects have been delivered through PPP with a value of about US$2.6 trillion (Zhao, Su, & Li, 2018).However, the PPP in China had evolved through various phases. The first wave of PPP expansion took place in the 1980s. Shortly after the opening in 1978, municipalities experimented with BOT projects in the 1980s due to decentralisation of authority. The first attempt in China was the Shenzhen government’s collaboration with a foreign company in a power plant construction(S. Zhang, Gao, Feng, & Sun, 2015). The second phase PPPs accounted for 36 percent of the total infrastructure investment by 1997 but PPP activities share of PPPs quickly dropped to 13 percent in 1998 and to 11 percent in 2002 following the Asian economic crises and issues relevant to poorly structured existing PPP projects which overburdened the government with too much risks and commitments (Chen & Doloi, 2008). The third wave of PPP activities was impacted by the end of world economic crises of 2008 and the ballooning local debts of municipalities. Due to rapid urbanization and increasing need for infrastructure, the central government saw the need to intervene by cleaning up the mess witnessed in the second phase by learning from previous mistakes and establishment of a regulatory PPP framework which induced the establishment of rules at local and regional levels that improved the growth of PPP in China as an infrastructure procurement system (Zhao et al., 2018). However, despite the growth of PPP in China there are issues of poor administrative structures that will align with the guidelines instituted by the governments which contribute to the resolving of the implementation issues. Similarly, there is absent of unified PPP law that can help clarifying the roles and responsibilities of stakeholders(S. Zhang et al., 2015). In addition to this, there is complete absence of the public participation mechanism which obstruct the public, as a stakeholder, from partaking in the designing of the project and in the implementation of the same (Zhao et al., 2018). Trust deficit also exists from the public due to the general culture of Confucian values which is oriented towards fair distribution of wealth rather than wealth production itself (Jong, 2012).

Indian Experience

India is increasingly recognising the importance of infrastructure to sustain its increasing urbanisation and economic growth with GDP growing at an average 7.7 % GDP per annum(Colmer, 2016). In that regard, it has keyed into the concept of PPP procurement with a steady rise in investment over the years. As has been detailed in figure 1, the procurement of infrastructure, in the tenth development plan, amounted to about 24% of infrastructure expenditure while in its 11th development plan, the investment in PPP constituted 36% of its infrastructure expenditure while in its 12th development plan it grew to 50% of its infrastructure investment amounting to about $ 8 billion . Telang and Kutumbale (2014)have reported that as at 2011, India had about 758 active projects. He noted that the success of PPP procurement strategy in India was amplified by the interest taken by the government to boost such partnerships through enactment of various laws and establishment of institutions.

South African Experience

South Africa adopted PPP as an infrastructure procurement strategy following the enactment of the PPP law in 1998. Infrascope ranked the country as the best African PPP market. The country has a strong business infrastructure, a sound financial sector and moderate standards in accounting, regulatory structures and law (The Economist Intelligence Unit, 2017). The budgetary provision of over $ 56 billion dollars for infrastructure provision over the next 3 years shall be partly financed through PPP. It is estimated that PPP projects shall account for about $ 1.3 billion representing 2.2% of the projected infrastructure provision by the government. PPPs in south Africa have a short pre-contract lifecycle relatively not more than three years(Oxford, 2019). Although there have been investments in energy projects especially in renewable energy sources, specifically 14 wind power projects and 13 solar energy projects. Similarly, there have been investments in transport and in the water and sewerage sectors, the majority of the PPP investments was in telecommunication sector with over US$27 billion (World Bank, 2015). The positive outcome can also be aligned to local ownership, shareholding and benefit sharing which is a quite exclusive to the south African PPP market but is vital set of requirements for PPPs in south Africa (Oxford, 2019). However, some projects have witnessed challenges such as opposition to the e-tolling on South Africa’s Gauteng freeway upgrade which is the largest infrastructure PPP project in Africa(The Economist Intelligence Unit, 2017). Issues such as high cost burden on citizens, ineffective and unreliable public transport option for the citizens affected the project. In addition, lack of stakeholder engagement and transparency in the project transaction process and poor public enlightenment about the project were identified as issuers which hindered the project (Manley & Gopaul, 2015)

2.5 Urbanisation and infrastructure in Nigeria

2.5.1 Introduction

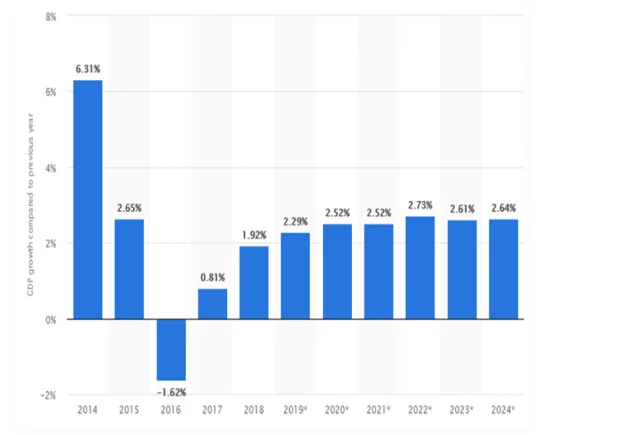

Nigeria is also Africa’s largest economy with a GDP of $1,951.42. It is presently the 8th largest producer of oil which is its major source of revenue. The growth in agriculture, telecommunications and services have positively impacted on its economic growth rate over the years (World Bank, 2020). However, in recent years its economic growth rate has declined see figure bellow plunging over 62% of its population extreme poverty and if the current trajectory is not checked, the amount of people leaving in extreme poverty will increase from present over 68 million citizens to 110 million people will be in extreme poverty by the year 2030 (Kharas, Hamel, & Hofer, 2018). Various scholars and multinational agencies have identified challenges affecting economic growth in Nigeria to be; policy implementation, corruption, exchange rate inconsistency, money supply and inflation rate and poor public infrastructure (Akekere, Oniore, Oghenebrume, & Stephen, 2017; Akinlo & Lawal, 2015; World Bank, 2016). The culmination of these issue have further impacted on the potential of the country to attract froing direct investment(African Development Bank, 2020; Lawal, 2016; Nwosa, 2019).

It is estimated that the population of the country is about 202 million people, it is Africa’s most populous country (World Bank, 2020). Nigeria is fast becoming a global urban giant (Fox et al., 2017). By the year 2050, it will become the third most urbanised country with 70% of its population living in urban areas, and will account for 10% of the of the global population (UNDESA, 2015). It is currently experiencing shifting demographics with greater number of cities emerging. As detailed in figure bellow, as of 1990 the country had 16 cities with a varied population that ranged between 300,000- 5 million in the year 2018 it was estimated 50 cities were estimated to exist with an urban population that ranged between 500,000 and 10 million and by the year 2030 about 67 cities will become urbanised with a population raging between 5000 and above 10 million.

2.5.2 The State of Nigeria’s Infrastructure.

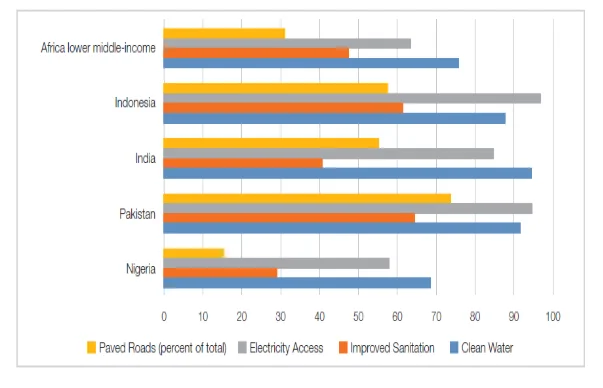

Nigeria primary delivers infrastructure through the traditional procurement route of direct funding which has not yielded the required results. Presently, there are over 19,000 uncompleted or abandoned public projects (Umoru & Erunke,2016), which are estimated to gulp over $ 47 billion and about 30 years to complete (Ewa, 2013). The dearth of efficient infrastructure, proper urban planning and the spontaneous nature of urban growth accompanied by diverse socio-economic, cultural and environmental issues has constituted serious challenges to urban growth and environmental sustainability in Nigeria (Adebimpe and Peters, 2018). Urban areas in Nigeria have not improved. Instead, they continue to experience a more impoverished situation in their physical infrastructure and social services, such as housing, roads, electricity, water, education and public health (UN Habitat, 2015). The analysis, illustrated in Figure 3, shows the data for 2016 for lower middle-income economies in Africa (African income peers) as well as for lower-middle global income economies (global income peers), specifically Pakistan, India and Indonesia. According to the International Futures forecasting system and the Traditional Infrastructure Index (World Bank, 2016), it shows that Nigeria had one of the lowest levels of access to improved basic infrastructure anywhere in the world, ranking 162 out of 186 countries.

The current stock of Nigerian infrastructure primarily procured through traditional procurement strategies has been subjected to project to corrupt practices, poor workmanship and failed infrastructure which has rendered the several sectors of the economy to lack competitiveness (Manu et al., 2019; Onolememen, 2020). For example, various surveys have highlighted that the efficiency of physical capital assets in Nigeria such as roads, public education facilities, electricity production, health infrastructure and access to treated water compared to other countries within the region is deteriorating and is responsible for about 40 percent of the productivity handicap faced by African firms. Raising Nigeria’s infrastructure stock would boost annual per capita growth rates by 4 percentage points and reduce poverty according to conducted simulations (Calderón, 2009; Sobjak, 2018). A recent report by IMF offered numerous solutions towards closing the infrastructure gap and improvement of efficiency. It highlighted that improvement of the quality of Nigeria’s governance practices to meet sub-Saharan African benchmarks could result in percent reduction in the efficiency gap. It emphasised several areas in improvement in public infrastructure delivery processes, such as improved public governance process which could cut overhead costs and improve expenditure management. Similarly, adoption of alternative infrastructure procurement strategies and multi-year budgeting strategies could lead to improvements in efficiency (International Monetary Fund, 2018). In an effort to bridge the infrastructure deficit in Nigeria, a thirty-year plan, known as the National Integrated Infrastructure Master Plan (NIIMP), was created. The Master Plan constitutes a financial road map for the investment in critical infrastructure across the country. The plan indicates that the transportation sector has an estimated budget of $775 billion, energy $1 billion, water and mining $400 billion, housing and regional development $350 billion, ICT $325 million, social infrastructure $150 billion and vital registration and security $50 billion. Meeting these illustrative infrastructure targets for Nigeria would cost $14.2 billion annually However, at present, Nigeria is spending only $5.9 billion on federal infrastructure leaving a substantial deficit of $4.6 billion (National Planning Commission, 2014). This represents around 7% of the GDP on infrastructure, although this is above the average for sub-Saharan Africa. However recent infrastructure budgetary provisions have been low, for example, in 2018 budgetary expenditure on infrastructure was equivalent to 2.3% of GDP. The government is also grappling with competing demands between capital expenditures and recurrent expenditure such as staff wages and overheads salaries. For example, statistics from Nigeria’s Budget Office indicate that recurrent expenditure was 147% of total revenues in 2018, denoting that the government was obligated to lend money to meet up recurrent expenditures (Business, 2020). Similarly available funds for infrastructure is susceptible to corruption especially large infrastructure projects (Sobjak, 2018). This situation has plunged about 60 percent of the urban population in Nigeria live in slums (Onyemaechi et al., 2015). To meet its infrastructure need over the next ten years and reduce its infrastructural deficit, research suggests a need to increase infrastructure spending to at least 12% of the GDP, this is an amount the Nigerian government cannot solely provide (SANUSI, 2012). To achieve this monumental task of bridging Nigeria’s infrastructure gap about 48% will have to be delivered through PPP while the outstanding 58% will be financed through direct funding from government (Oyedele, 2019).

2.6 Nigerian PPP Experience

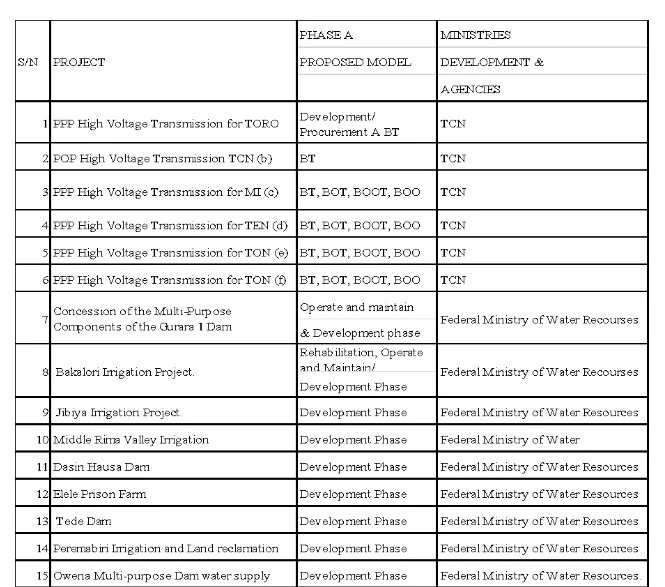

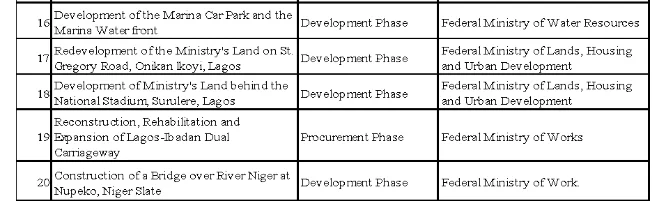

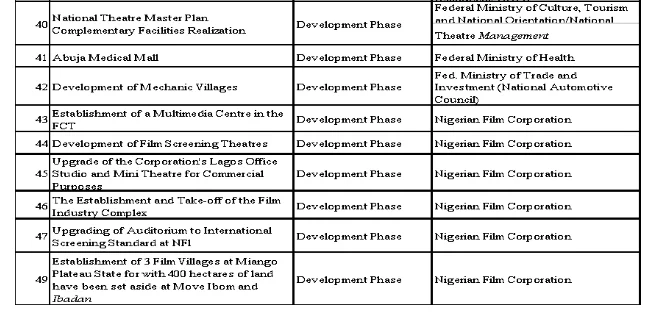

PPP infrastructure projects are increasingly becoming popular in Nigeria especially with the enactment the comprehensive National Policy on PPPs in 2009 (Infrastructure Concession Regulatory, 2013). Especially with dwindling government resources and increasing need for new infrastructure and improvement of existing stock, both the federal government and the states have been adopting PPP to bridge infrastructure deficit (Erumebor, 2017). The system of governance in Nigeria is Federation type. The government is divided into the federal , the state and the local governments. There are issues the federal government has sole responsibility to legislate upon, similarly there are those that the state government only may pass laws for items on the residual list whereas the federal government has exclusive right to legislate on issues on the exclusive. The PPP law falls within the concurrent list. . The PPP law in Nigeria exists at the federal level and at some states in the country (G. Nwangwu, 2016). This means that where projects intersect with federal government jurisdiction states must seek approval from the federal government to embark on such projects. The Infrastructure Regulatory Commission (ICRC) is an agency set up by the government to scrutinize FGN's PPP project proposals and monitor execution. It serves as an independent advisory that guides the FGN in its decision to adopt PPP to deliver infrastructure projects through PPP procurement strategy. It also assists state governments in building capacity and diffusing best practices in their bid to establish local frameworks and laws (ICRC, 2012). Indeed, the enactment of the PPP law and establishment of the PPP Unit has improved the PPP investment climate in Nigeria with numerous projects that cut across social and economic infrastructures such as hospitals schools, power generation, telecom, housing roads etc. As detailed in the table 6 below Nigeria has adopted various forms of PPP procurement strategies and many projects are at various stages of execution.

2.6.1 PPP Institutional Framework in Nigeria

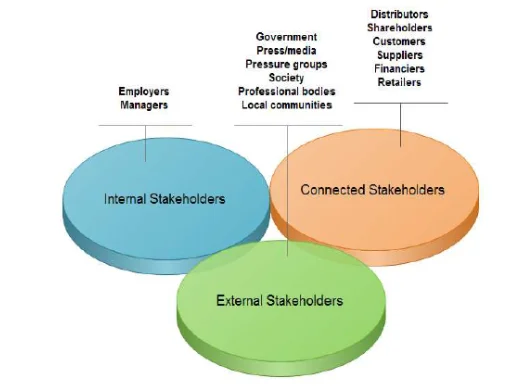

The institutional framework in Nigeria cut across all ministries and parastatals in the Federal government (Infrastructure Concession Regulatory Commission, 2017). As detailed in figure 14 bellow, the PPP framework in Nigeria specifies roles and responsibilities to relevant government organisations and federating units. As stated by Jomo, Chowdhury, Sharma, and Platz (2016) PPP frameworks tries to foster harmonious working relationships between the various governments and private stakeholders in the PPP process by ensuring that there is orderliness in the system and transparency in the decision-making process. Though the Nigerian PPP framework as detailed captures government stakeholders concerned with the project being considered and ensures they partake in the decision-making process from initiation to execution. However, the complexity of a PPP institutional framework affects the decision making process, final configuration of the project and hence, its performance within the project lifecycle (South, Levitt, & Dewulf, 2015; Van Gestel, Voets, & Verhoest, 2012). Moreover, Grimsey and Lewis (2002) asserts that PPP projects are complex because there are multiple numbers of stakeholders involved with a different yet competing interest which must be balanced. The institutional framework indicates decision points and the various stakeholders involved, yet at every point, the decision is done in silos which may create mistrust, increased bureaucracy and conflict of interests among stakeholders especially the public and legislative arm of government. This is validated by the findings of Solomon Olusola Babatunde, Perera, Udeaja and Zhou (2014) where they established that the Lekki-Epe Expressway toll road concession in Lagos, Nigeria suffered implementation setbacks due stakeholder resistance within the political and public spheres. Similarly, the institutional framework does not clearly capture the non-governmental organisations and community representatives as stakeholders in the decision-making process. Nigeria Infrastructure Advisory Facility (2017) asserts that poor stakeholder engagement contributed to community resentment of the PPP projects especially those that are user fee inclined, thus,. . The MMA2 case also highlights that management of politicians ‘expectations and setting realistic project goals hampered the smooth operation of the project. This calls for a strong contract management capability within the Government team. It is also captured in literature that lack of expertise of both the public and private sector stakeholders have been further highlighted as one of the major causes of PPP project failure in Nigeria (Ahmed, 2011; S. Babatunde, 2015).Various researchers have also established that public and private partners’ capacity deficiencies regarding management competency such as stakeholder engagement, is a major barrier to effective PPP project delivery in developing countries (Y. Ahmed & I. Sipan, 2019; Umar, Zawawi, & Abdul-Aziz, 2019; A. Walker, Ameyaw, & Chan, 2015). A recent assessment of PPP environments of 15 African countries ranked Nigeria 13th in terms of enabling environment (The Economist Intelligence Unit, 2015). Hence improved capability of the public and private partners in PPPs in Nigeria can help in the successful delivery of PPP projects (Solomon Olusola Babatunde, Perera, Zhou, & Udeaja, 2016; G. Nwangwu, 2016). In view of the importance of stakeholder engagement to successful deliver PPP projects and the lack of skills within the PPP landscape in Nigeria, it becomes desirable to develop a stakeholder engagement readiness framework for both government and private sector organisations involved in PPP infrastructure projects in Nigeria.

Regarding the regulatory framework, some pieces of legislation, including Privatization and Commercialization Act (1999); the ICRC Act of (2005); the Fiscal Responsibility Act (2007), and the Public Procurement Act (2007); were identified in the National Policy on PPP as being relevant to PPP transactions in Nigeria.

Especially in stakeholder engagement related capabilities as it has been identified as a crucial success factor which is hindering the potential of PPP development in Nigeria (G. A. Nwangwu, 2013)

2.6.2 Key Challenges of PPP Implementation in Nigeria

2.6.2 .1 Regulatory related challenges

PPP contracts rely on robust contract governance to ensure that the responsibilities of the private and the public sectors are clearly defined and adhered to (Grimsey & Lewis, 2004). The structure of the PPP Act in Nigeria has restricted authority of The ICRS to ensure compliance with contract terms especially at the government end (Solomon Olusola Babatunde & Perera, 2017b; M. Dada & Oladokun, 2012). In addition, the existing framework does not protect private sector stakeholders framework that need to be put in place so as to empower the public authorities to enter into agreement with the private sector and as well protect the interest of the private sector (Solomon Olusola Babatunde, Opawole, & Akinsiku, 2012; Onuorah, 2014). (M. Dada & Oladokun, 2012; Onuorah, 2014) that there is absence of guidelines to guide public authorities on the drafting of the PPP contract (M. Dada & Oladokun, 2012; Onuorah, 2014) . There are multiple laws in existence which are in conflict with each other creating infighting between government organisations which have oversight (Idris, Kura, & Bashir, 2013; Ikpefan, 2010) For example, due to policy inconsistency a conflict between the ICRC Act and the Privatisation Act presently exists (African Legal Support Facility, 2019; G. Nwangwu, 2018).The ICRC and the Bureau for Public Enterprise BPE were created under both government legislations respectively with similar schedules constantly competing over projects, creating an atmosphere of certainty as to which of the two organisations should have authority over privately financed projects (Abdulsalam, 2014; G. Nwangwu, 2018).There are too many inconsistent government policies and care-free attitudes in the government which could affect the general economy and PPP projects (Idris et al., 2013; Taiwo, 2013). In Nigeria, due to poor political will, PPP projects can be revoked, or a fresh concessioner could be invited in the event a new set of political figures emerge in government. In addition, vested interests in the country in the political and elite circle against PPP can frustrate the project often at the early stage of the project. There are likelihood of corruption and bureaucratic bottlenecks associated with getting approvals which reduces the prospects of investors to partake in the project (Adebiyi, Sanni, & Oyetunji, 2019; Bhanu & Stone, 2016; M. Dada & Oladokun, 2012; Ibietan & Joshua, 2015; Idris et al., 2013) .

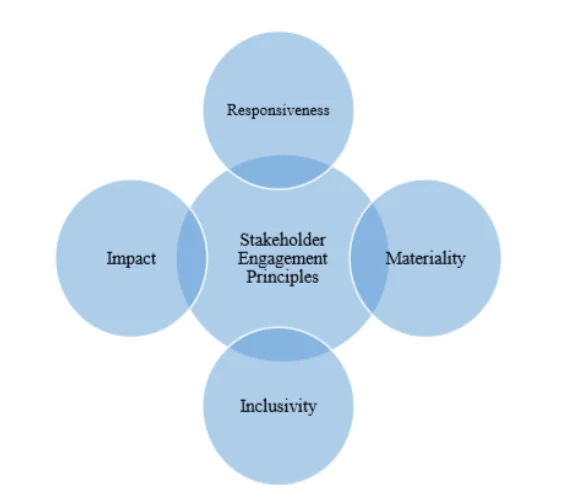

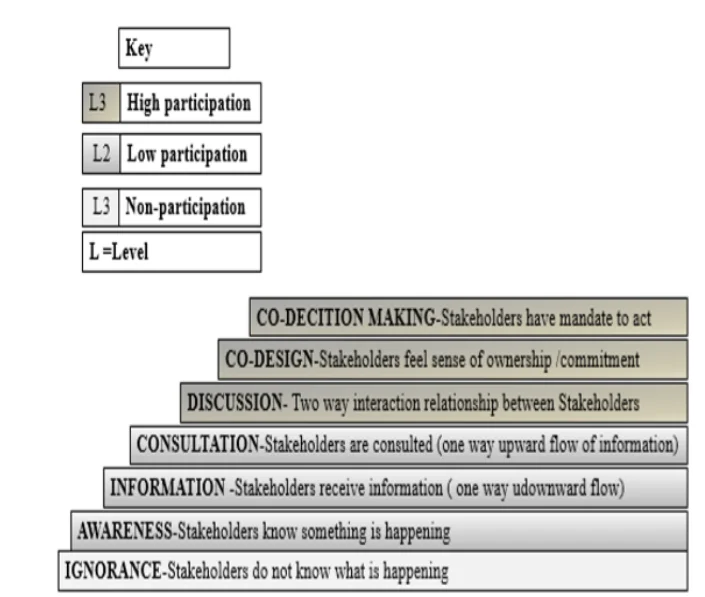

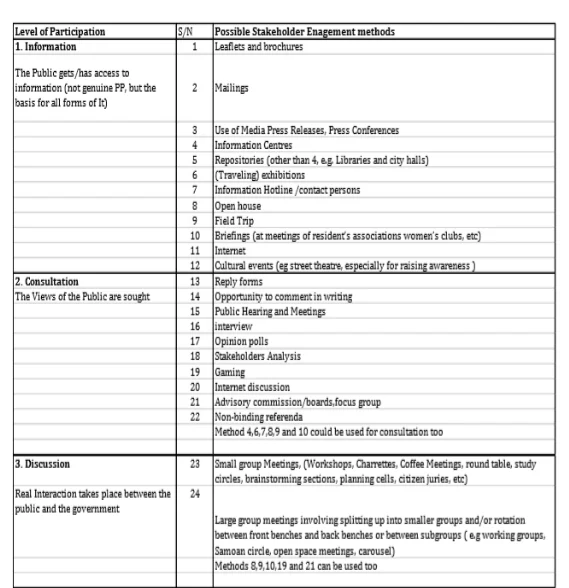

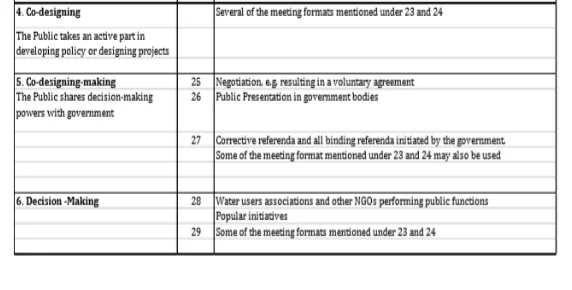

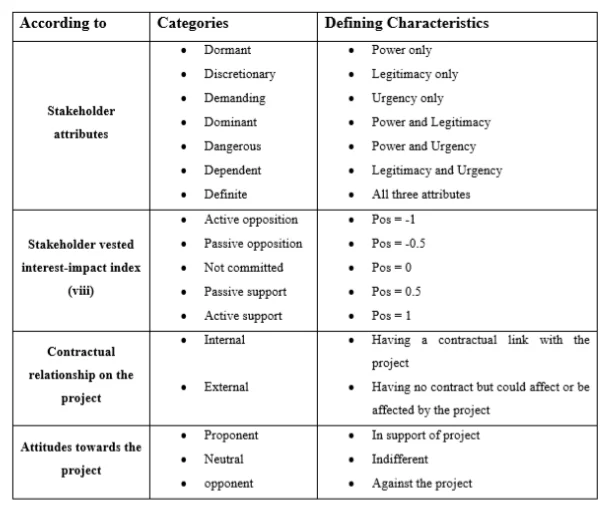

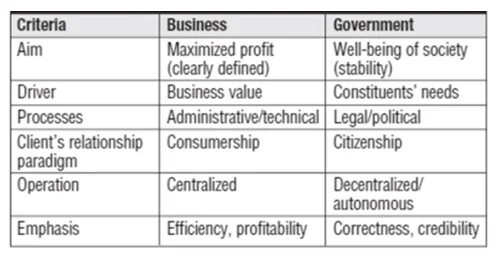

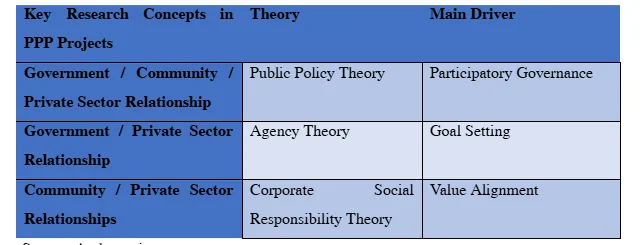

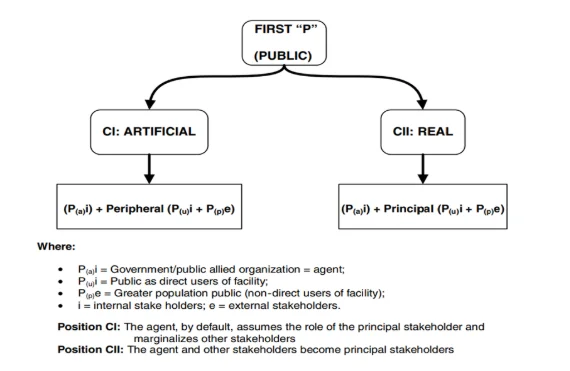

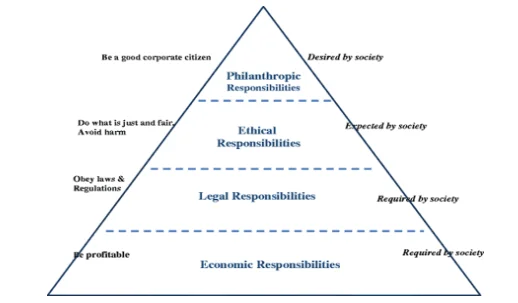

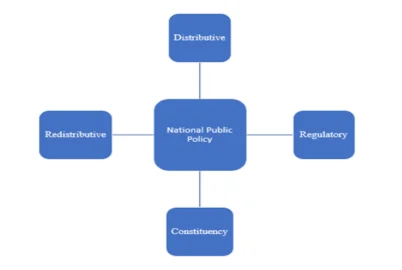

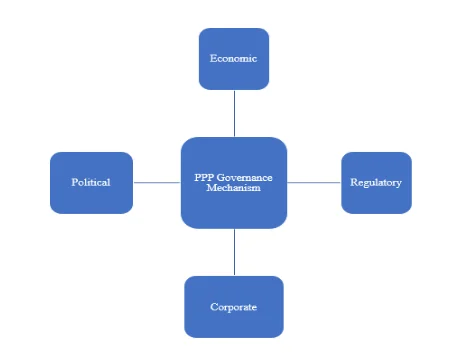

2.6.2 .2 Legal related challenges