Diversity of Special Economic Zones

1.0. Introduction

1.1. Defining Special Economic Zones

For more than half a century, SEZs have played a substantial role in the development of the economy, industrial growth, and international trade (Farole & Akinci, 2011). In the analysis literature, there are many different definitions of special economic zones (SEZ). Additionally, there is a wide variety of SEZs. The expression “SEZ” coats a wide range of zones, such as export processing zones (EPZ), free trade zones (FTZ), industrial parks, high technology zones, economic and technological development zones, free ports, enterprise zones, science and innovation parks, and others (Looser, 2012; Zeng, 2015). However, in general terms, SEZs can be defined as geographically delimited lands located within national borders of a country, where the principles for doing business differ from those that dominate in the national terrain (Farole, 2011 p. 23; Frattini & Prodi, 2013). Furthermore, SEZs usually functions per more liberal economic rules than those that generally prevail within states. The outcome of these improved circumstances is that SEZs are equipped with a business environment that is designed to be more conducive to added value throughout private investment in terms of politics and more efficient from an administrative attitude than in the national territory. The development of SEZs programs is based on many diverse reasons for choosing them as a policy tool. In general, however, they are usually interested in achieving a number of economic and political goals, such as growing foreign direct investment (FDI), promoting economic reforms, creating jobs, advanced training, technology and innovation transmission, increased productivity of local companies and using as experimental laboratories for new politics and strategies (Farole, 2011; Farole & Akinci, 2011; Lin & Wang 2014; Zeng, 2010).

1.2 A brief history of SEZs in International Political Economy

History of modern SEZs begins with the Shannon Free Zone in Ireland, established in 1959 (Farole, 2011; Zeng, 2015). The Shannon contributed the basic rules for SEZs, which was reproduced over the vast territory of the developing countries in the following decades. Since the 1970s, SEZs primarily established in the form of EPZ and were created in East Asia and Latin America for attracting FDI to labor-intensive manufacturing clusters to stimulate exports (Chen, 1995; Farole 2011). This was a deviation from the traditional policy of import substitution. EPZs, as a rule, are fenced areas with strict customs control, and most of the commodities (usually more than 80%) manufactured in the zones should be exported. This type of SEZ has been successful in a lot of economies, such as China, the Republic of Korea, Vietnam, Taiwan, Bangladesh, Dominican Republic, Mauritius, etc. (Arnold, 2012; Zeng, 2015). Since the 90s, SEZs have undergone significant changes, and the categories of permitted actions have enlarged remarkably. SEZs have become a vital political tool for many states aiming to attract FDI and create jobs (Farole, 2011). Over the last four decades, their popularity as a policy instrument has increased significantly. For instance, according to the International Labor Organization (ILO), in 1986, a database showed 176 zones in 47 countries; by 2006, 3,500 zones were registered in 130 countries (Aggarwal, 2012; Farole, 2011; Farole & Akinci, 2011; Zeng 2015). Nowadays, there are about 5,400 zones in 147 countries compared to 4,000 in 2014 (UNCTAD, 2019). Moreover, over 500 new SEZs are under development. SEZs are broadly created in most emerging and many advanced countries. Inward these geographically demarcated lands, governments promote industry throughout tax and regulatory impetuses and infrastructure maintenance (UNCTAD, 2019). Nowadays, SEZs are mainly located in East Asia, as well as in the Middle East and Africa (Farole, 2011). The boom of SEZ is a piece of a new wave of industrial strategies and a reaction to the growing competition for universally liquid investment (UNCTAD, 2019). They also contributed to consolidation with global trading and structural changes, covering industrialization and modernization processes.

1.3. Literature review and theoretical approach

An examination of the research topic has led to a more targeted choice of research material: from creating the theoretical foundations of establishing SEZs around the world to survey information available on comparative analyses of SEZs in developing countries. The literature on SEZs commits a vital endowment to our comprehension of globalization with neoliberal approach and themes such as attracting FDI, labor rights, export-based development results, and post-socialist practices with a market economy (Arnold, 2012). Some instruments of economic development tools such as SEZs were arguable, in particular, EPZ type. They were the topic of intensive contradictory debates during the last four decades on virtually every factor of their forms, meanings, and influence. These debates focused on core economic concerns, including spillovers of FDI, job, and incomes, as well as environment and gender (Farole, 2011 p.44). SEZs have mixed evidence of success. According to Farole & Akinci (2011), some personal data cites a variety of instances of infrastructure investments in zones leading to the emergence of "white elephants" or zones that have primarily led the industry to take advantage of tax incentives without significant employment or export revenue. Although the international political economy literature suggests that empirical studies illustrate a lot of SEZs were useful in developing exports and jobs, they were marginally beneficial in estimating costs and benefits (Chen, 1993; Jayanthakumaran, 2003; Madani, 1999; Warr, 1989). Furthermore, the authors claim that a lot of standard SEZ programs were prosperous in attracting investment and job creation in the short term, but have not been able to stay stable while employment wages rose and favored access to trade no more provides satisfactory benefits. However, there are notable similarities in SEZs throughout the majority of articles, mainly because of their general view of SEZ (Farole, 2011; Farole and Akinci, 2011; Frattini & Prodi, 2013). Some of the examples depict the catalytic role that zones play in economic development and regulation procedures (Madani, 1999). For instance, a lot of zones created in the four “Asian Tigers” countries in East Asia in the 1970s and 1980s played a decisive role in promoting their industrial growth and modernization actions. Likewise, the subsequent enactment of the SEZ model by China since 1979 and the introduction of the SEZ on an unprecedented scale allowed created a field for engaging FDI in a transitional economy. Moreover, it helped in the growth of the manufacturing sector in China. Besides, maintained as an impetus for large-scale economic changes, which were later distributed within the state (Farole & Akinci, 2011; Madani, 1999). Although the literature provides a wide range of analytical and comparative analyses on SEZs around the world, there is a gap like the lack of comparative studies of SEZs between Kazakhstan, China, and South Korea. The theoretical aspect of this project will intend to explain the SEZ in terms of the neoliberal approach. As Harvey (2007: 2) defines, "Neoliberalism is a theory of political and economic activities that assumes that human well-being can be best achieved by freeing individual entrepreneurial freedoms and skills within an institutional framework characterized by strong private property rights, free markets, and free trade." According to Farole (2011), reforms in the international political economy in the 1980s finished the internal policies of the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. Neoliberalism has led to the elimination of protectionist policies of these eras. A lot of research argued that SEZs lost their pertinence in this new climate because investment and trade barriers have been dismantled in the age of globalization (Farole, 2011).

Nevertheless, according to the World Investment Report 2019, the number of SEZs continues to increase sharply (UNCTAD, 2019). Likewise, most economists suppose that SEZs can provide more efficient and effective industrial development (Lin & Wang, 2014). According to Lin and Wang (2014: 15), mainly, investment in SEZs can: (1) ensure the integration of public services in a geographically demarcated land; (2) increase the effectiveness of limited public funding/infrastructure budget; (3) promote the growth of clusters or agglomeration of definite industries; (4) stimulate urban improvement - ensuring favorable living settings for employees and the scientific and technical staff, as well as the conglomeration of services, including economies of scale from environmental facilities, such as wastewater treatment plants and reliable waste treatment plants. Therefore, the authors suggest that zones can help create jobs and generate income, and possibly protect the environment and promote green growth and green cities. However, this paper will examine both the positive and negative effects of the neoliberalism approach, which apply through SEZs in terms of providing a critical analysis. As many scholars claim, over the past forty years, the liberalization of economic politics and the spread of new commercial tools have become the most significant economic growth worldwide (Simmons & Elkins, 2004). SEZ can serve as a political tool for financial liberalization, facilitating trade and expanding the use of resources, including FDI, and making a contribution to economic growth (Ge, 1999; Park, 2005). For example, foreign capital may be the deciding factor for developing countries due to the lack of resources and domestic savings. This eliminates the capital deficit, accelerates, and upgrades the domestic industry (Lin & Wang, 2014). Moreover, by using local employees and managers, companies with foreign investment can train local workers to learn management, marketing skills, and production activities (Madani, 1999: 42). Similarly, entering an international market gives domestic companies access to new technologies, and at the same time, competition forces local companies to introduce the latest technologies (Farole & Akinci, 2011; Frattini & Prodi, 2013; Zeng 2010, 2015).

1.4 Research proposal and research question

The relevance of the research topic is determined by the increasing demand for Kazakhstan for export orientation and economic diversification by the development of industrial clusters, which was destroyed after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Kazakhstan is located in Central Asia and does not have direct access to the sea (landlocked); thus, it has certain limitations to the international market. This means that exports have to travel long distances and across borders to reach the global markets and main logistics hubs. However, Kazakhstan is rich in natural resources, particularly oil and gas, which recorded for more than 60% of its exports and almost 25% of its GDP (which year) (CAREC, 2018). Furthermore, in Kazakhstan, the main clusters attracting the most significant amount of investment are oil, gas, mining, and other related services. Presently, as part of Kazakhstan industrialization program, the state is focusing on the following sectors as priority for investment in order to facilitate the Kazakhstan economy diversification: (1) oil and gas equipment; (2) textile; (3) agriculture and food industry; (4) construction; (5) building materials; (6) tourism; (7) metallurgy; (9) transport and logistics (Kapparov, 2012; Wandel 2010). The researched information on the relationship between SEZs in Kazakhstan and industrial development gives a perception of the current situation of SEZs and challenges faced by the Kazakhstan strategical meaningful industrial clusters that are part of the industrialization program of Kazakhstan (Wandel, 2010). According to Kapparov (2012), the creation of SEZs is one of the tools that Central Asian states use to increase FDI and guide them to specific sectors of the economy. In 1994–2015, the inflow of FDI in Kazakhstan was more than in other states of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) (CAREC, 2018). However, the production cluster of Kazakhstan could not attract much FDI for development, especially in the profitless textile industry (Petrik at al., 2017). Thus, a common problem of Kazakhstan SEZs is that they are not being used to their full potential in economic development (CAREC, 2018). These shortcomings can be eliminated by conducting comparative analyses of the processes of the SEZ in China and South Korea. These countries were not chosen by chance. Firstly, the choice was made because of the neighborhoods that Kazakhstan and South Korea have with China, which is one of the largest economies in the world. Secondly, South Korea, being China's eastern neighbor, is one of the Asian tigers (Konkakov & Kubayeva, 2016), and their experience of SEZ is essential for studying. Thirdly, a definite success case with SEZs is China (CAREC, 2018; Zeng, 2015). Their pioneered experience in the field of SEZs may be of particular importance for Kazakhstan since the Chinese SEZs have been successfully used as instruments to ensure the transition of China's economy from a centrally planned to a market. Moreover, SEZs in China oriented to increase export and attract FDI in terms of creating opportunities for technology transfer and create more skilled jobs (CAREC, 2018; Zeng, 2010).

Besides, the scientific novelty of this study lies in a comparative analysis of the functioning of South Korea SEZs as a neighbor of China, since this country can (is it can or cannot?) develop its economy without referring to the economic or demographic power of its neighbour. Thus, this country can serve as an example in studying the role of SEZ in the economic development of Kazakhstan, because Kazakhstan also borders China. In this way, this paper is aimed at studying SEZ activities in economic growth of Kazakhstan by analysing SEZ processes implementation in industrial clusters by studying China and South Korea’s SEZ in order to answer the critical question of this thesis “what is the role of SEZs in economic development of Kazakhstan through comparison with the experience of China and South Korea?”

1.5 Methodology and Thesis structure

This thesis compares how China and South Korea realised and liberalised SEZ procedures and how they governed the industry clusters in these countries by using SEZs. This cross-national approach raises analytical leverage to examine the relative importance of SEZ activities. Moreover, their economic and technological conditions inherent in a sectoral development to explain national patterns of growth in emerging countries. Also, this research will use qualitative analysis of empirical evidence to support the study. Moreover, the research methods will draw evidence from secondary data to systemize the founded information from both practical and theoretical attitudes. The role of a comparative analysis of the activities of SEZ in Kazakhstan and the two target countries is significant, because when the research is implemented, it may not have enough empirical data in similar economic conditions. This type of analysis is not embodied at a more serious methodically adequate level in the foreign and Kazakhstani economic literature. Moreover, the lack of general agreement on definitions of SEZ and the lack of exhaustive and transparent data of SEZ Kazakhstan make difficulties in determining the real impact of SEZs on economic development. It should be noted that data on the SEZ of Kazakhstan are also limited in content and latitude. (Propose-Magnitude) The research is structured as follows. (Outline structure of chapter one if necessary) Chapter two introduces SEZs in Kazakhstan with an objective to investigate their role in Kazakhstan's economic development and its impact on industrial growth. The chapter also explores the activities of Kazakhstan SEZs. Besides, it illustrates SEZs establishment purposes, regulation procedures by the government of Kazakhstan, including their significance in the development of Kazakhstan. Moreover, it analyses the investment climate in Kazakhstan for attracting investment in SEZs. In addition, it examines positives and negatives implicit on SEZs of Kazakhstan to establish what aspect of their implementation might benefit from comparison with China and South Korea cases. Chapter three considers the empirical facts of China and South Korea. This chapter investigates the available evidence which is related to SEZs and development in these countries. Likewise, it examines the SEZs reforms and their positive and negative effects on increasing economic conditions. Moreover, this cross-national examination increases the analytical capability to study the relevant value of state policies and financial circumstances implicit on SEZs. The comparative analyses of SEZ activities in China and South Korea will allow the identification of the strengths and weaknesses that can contribute to the emergence of suitable activities for their possible adoption by SEZs in Kazakhstan and their industrial clusters. Chapter four is the conclusion which summarizes the outcome of the study. This chapter will summarise the empirical experiences of SEZs in case study countries and present specific recommendations for further possible adoption of their effectiveness by Kazakhstan.

2. SEZ in Kazakhstan

2.1 SEZs performance in Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan is the ninth-largest state in the world, with a population of over 18 million people. Over the last decade, its economic development rate was among the leading economies globally. This made it possible to achieve the status of a country with an average income and low levels of poverty and unemployment. The first President of Kazakhstan introduced a view and program "Kazakhstan 2050" for the nation in December 2012. This ambitious vision posits that Kazakhstan will be among the top 30 developed states by 2050, not only in terms of per capita income but also in broad measures of social, economic, and institutional growth (Aitzhanova et al., 2014). Kazakhstan is the last republic that became independent from the Soviet Union in 1991. Over the years of independence, the state has achieved significant strides in increasing its economy and implementing fundamental changes as it transitions from planned to a market economy. Furthermore, Kazakhstan has a high potential for economic growth because it has distinctive mineral reserves. For instance, according to World Bank appraise, Kazakhstan still has over 5,000 undiscovered deposits of minerals worth more than 46 trillion USD (Kazakh Invest, 2019). This Central Asian country rank first globally in reserves of zinc, tungsten, and barite; second in chromite, silver, and lead; third in fluorite and copper; fourth place in molybdenum and sixth place in gold. Likewise, Kazakhstan ranks Eighth in coal reserves in the world and second in uranium sources. Kazakhstan is among the ten largest world exporters of grain and one of the dominant exporters of flour (Kazakh Invest, 2019). Its enormous natural resources and oil prices might lay the foundation for economic development. For example, according to Lin & Wang (2014), each nation has a base that includes land and natural resources, human and physical capital, which consist of the overall affordable budget that a country can direct for industries to increase the production of goods and services. This basis indicates that plenty of state resources define the optimum structure of the industry, which might enlarge state competitiveness. Moreover, Kazakhstan has considerable oil and gas reservation. The country ranks ninth in the world in explored oil resources, which are eliminated in the western regions. However, the most significant anxiety is over-reliance on the oil and mining industries in Kazakhstan (Kapparov, 2012). Likewise, in Kazakhstan, FDI and domestic investment are primarily focused on the oil-producing and metallurgical clusters of primary production (CAREC Programme, 2019), sidestep the secondary industry that is also the disadvantage of the current economic situation of Kazakhstan. These drawbacks the Kazakhstan government is trying to solve by adopting an industrialization programme for diversification of the economy (Nurzhanovna, 2011). As in many emerging countries, the goal of industrial policy was to stimulate the transition from mining and export of predominantly unrefined raw materials to the production and export of more high-tech and value-added goods (Guimón, 2013). To accelerate this transition and increase competitiveness in targeted clusters, the Kazakhstan government has put the issue of improving the state innovation and industrialisation policies in the priority place (CAREC, 2019). According to Lin & Wang (2014), SEZs as a tool of economic reforms can afford more active and efficient industrial growth. Furthermore, governments of developing countries often create SEZs to provide liberalised investment and economic politics on a small scale before implementing them throughout the country (Kapparov, 2012). This is obvious to avoid a likely conflict with current economic, social, and political structure due to instantly foreign involvement in the industrialization programme.

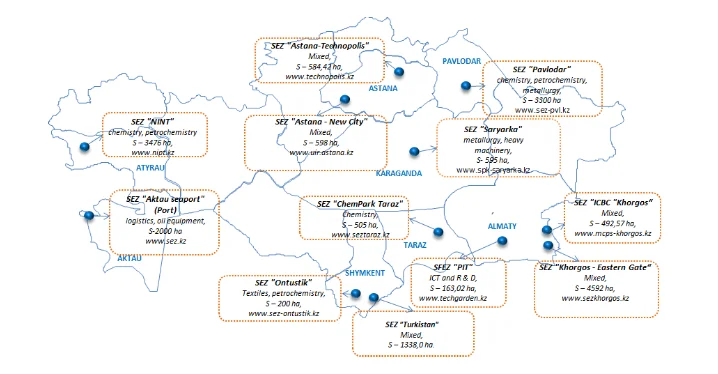

As Kapparov (2012) claims, succeeding in the practice of different states, the aim of creating SEZs in Kazakhstan as an instrument of economic development was the diversification and growth of the economy by attracting FDI, increasing manufacturing, enhancing export, import of technology and skills. For instance, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) research in 2015 illustrates that emerging Asian states with SEZs have 82.4% more FDI than emerging Asian nations without SEZs (CAREC, 2019: 65). Moreover, the activities of SEZs must be linked with the long-term plans for the industrial, social and innovative development of a country, which is an essential aspect of enhancing the role of SEZ in the development of zones themselves, hence the growth of the country economy (Kapparov, 2012). Besides, in Kazakhstan, there is the Ministry of Investment and Development of the Republic of Kazakhstan. It is the state agency of Kazakhstan that regulates the industry and industrial-innovative spheres, the state investment policy, and the policy of providing investment support. It also creates favorable conditions for investment climate; establish, operate, and liquidate of SEZs; implement of state policies to support investment and other industrial clusters (Kazakh Invest, 2019). This means that the Kazakhstan government, while creating this public agency, identified SEZs as an essential aspect of national economic growth. Existing SEZs in Kazakhstan placed within the state's national borderline, which has a distinguished juridical reign, with the entire required infrastructure, to perform actions in preference areas (Kazakh Invest, 2019). Nowadays, in the land of Kazakhstan, there are 12 special economic zones with various sectoral directions (Map 1).

The following purposes of establishing Kazakhstan SEZs declared by Kazakh Invest (2019): SEZ "Astana - new city" – hasten construction of new business and administrative hub of the capital and the starting of new industries; SEZ “Saryarka” - the increasing of the metallurgical industry, especially the manufacturing of finished goods by engaging producers of world brands; SEZ “National Industrial Petrochemical Technopark” - improvement and execution of advanced investment projects for the establishing and increasing of first-rate petrochemical factories and the producing high competitive petrochemical goods with high added value; SEZ "Aktau Sea Port" - the attraction of foreign and domestic investment in projects with export direction; increasing of innovative technologies for import substitution; SEZ “Chemical Park Taraz” - development of the chemical cluster as a part of the state strategic program “Kazakhstan 2050”; SEZ “Khorgos - East Gate" - considered as a vital object and a logistics hub connecting the Middle East, Central Asia, and China; SEZ "Park of Innovative Technologies" - development of information technologies, renewable energy, reserves conservation and effective use of natural resources, technologies in the field of extraction, transportation, and refining of oil and gas, development of new types of commodities, investment; SEZ "Pavlodar" - development of the chemical, petrochemical industry technologies, notably the production of products to export with added value; The SEZ “Astana - Technopolis” - innovative development of Astana city by increasing investments and using advanced technologies, know-how and the creation of modern infrastructure; SEZ "Turkestan" - hasten the development of Turkestan city, development of competitive tourism area, production of a unified information base for tourist services; SEZ “ICBC“ Khorgos ”- development of cross-national trade and economic collaboration, increasing of export orientation, improvement of transport and tourism infrastructure; SEZ "Ontustik" - advancement of the textile industry, attracting producers of world brands of textile commodities, the establishment of high-tech technologies;

As seen from the previous, each SEZ is distinguished due to its goals of creating, such as economic, geographical, and industrial specification. Likewise, Kazakhstan SEZs are geographically remote from each other and encompass their districts, as well as investment programs of SEZs, which are mainly focused on production. Although the light industry is one of the priority sectors of the economy of Kazakhstan, the majority of the 12 SEZs are focused on heavy industry.

2.2 Success and failure of SEZs in Kazakhstan

According to (CAREC Programme (2019: p.4), the Kazakhstan government adopted its first law on SEZs in the 1990s, and nine SEZs were created during this decade. However, by 2000, they had to be canceled owing to their not-profitability, which was consequences of deficiencies in the legal base, poor locations, lack of transparency, and subsequent corruption (CAREC, 2019). Afterward, this law has lost force with the ratification of the new Law of the Republic of Kazakhstan dated July 21, 2011, "On special economic zones in the Republic of Kazakhstan." Obviously, it was a second effort to modify SEZs in Kazakhstan because SEZs should have been adjusted to the developing international market, particularly before recent Kazakhstan joining the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2015 (CAREC, 2019). After the start of the second attempt to develop SEZs in Kazakhstan, the government showed a growing willingness in the development of SEZs. The government of Kazakhstan is making efforts to increase investment in macroeconomics and microeconomics levels. These attempts might be considered as a growing willingness of the government for developing the economy and industry clusters throughout SEZs in Kazakhstan. Besides, adoption of the productive investment policy might be one of the core aspects of the outstanding implementation of the industrial programme of Kazakhstan throughout SEZs (Kapparov, 2012). To achieve this goal, the Kazakhstan government established JSC National Company 'Kazakh Invest' in 2017. This company is a national agency for attracting investments to the Republic of Kazakhstan. Kazakh Invest provides a full range of services to support investment projects from idea to implementation on a "one-stop-shop" basis and acts as a single focal point for SEZs of Kazakhstan. Thus, it plays the role of a sole negotiator representing the interests of the Government of Kazakhstan in discussing the prospects and conditions for the implementation of investment projects through SEZs (CAREC, 2019; MIID KZ, 2019). Kazakh Invest has a network of representatives abroad. This company is a part of the Ministry of Investment and Development of the Republic of Kazakhstan, financed by the republican budget and provides its services at no cost (MIID KZ, 2019). Likewise, it is a national operator of the system for the development and promotion of non-resource exports. Thus, this might be considered as a third attempt of the Kazakhstan government to increase SEZ activities to improve their cost-effectiveness by the government of Kazakhstan. This illustrates that the role of the state in the development of SEZs in Kazakhstan is significant. Moreover, according to Omarova (2015), Kazakhstan is rightfully taking a leading position between countries of CIS in providing the most friendly climate for attracting investment. Kazakhstan's investment climate is provided by a conjunction of availability of natural resources, the market size, the geostrategic location, as well as a steady political condition and an appropriate legal base. As the author claims, supporting a convenient investment environment in Kazakhstan encloses the succeeding priorities: an advantageous tax regime, economic and political stability, the establishing of SEZ, an intelligent system for managing the investment process, and then making an appropriate investment law. On the other hand, Kazakhstan SEZs contain the next key performance indicators: domestic investment and FDI; production; the amount of SEZ members; created jobs and local content (CAREC, 2019: 31). Regardless of whether some Kazakhstan SEZs' goals in manufacturing, export, investment, or employment have been achieved, there is no persuasive factual data that any of these indicators has been considerably increased (CAREC, 2019; CAREC Programme, 2019).

Although during the last two decades total FDI attraction to Kazakhstan was the largest among CIS countries (UNCTAD, 2019: 183), according to available data for 2015 the cumulative FDI in all SEZs accounted for merely 8% of the total investment, which is significantly lower than the general target (CAREC, 2018: 64). For instance, according to Petrik at al. (2017), in the SEZ, "Ontustik" initially projected to attract 1 billion USD investments and construct 15 plants, which would constitute a complete cotton processing cycle. However, the actual figures depict that only 8 out of 15 factories in this SEZ operate investments of approximately 150 million USD, which is mainly through government lends (Petrik at al., 2017: 442). This means that the economic efficiency of the SEZ “Ontustik” showed considerably lower outcomes compared to what was expected. Consequently, SEZs were unlikely to benefit from any investment benefits. Moreover, the lack of investments in all Kazakhstan SEZs is a severe obstacle to their performance, as well as the development of industrial clusters (CAREC, 2019). Also, as discussed earlier, the majority of investment in Kazakhstan is focused on mining, oil, and gas segments. Production (exceptionally light industry) and services sectors could not attract the necessary level of investments (CAREC Programme, 2019). Furthermore, FDI is the primary origin of not only funds but also technical progress and knowledge in the field of management and, consequently, total factor productivity (TFP). For instance, Nurzhanovna (2011) claims that currently, the textile industry in Kazakhstan provides merely 10% of domestic needs despite the expectations that it should satisfy at least 30% of domestic demand for economic stability. Obviously, the government is involved in laying the foundation for developing the priority textile industry in Kazakhstan by creating the SEZ "Ontustik," state agencies, and regulatory framework, as mention earlier. The SEZ "Ontustik" is considered as the foundation for the advancement of the textile industry that might promote Kazakhstan textiles to enter the international market. On the way to this, there is a severe flaw, which is the absence of a quality human capital (Petrik at al., 2017). In Kazakhstan, few textile producers fall short of engineers, technologists, operators, weavers, and Seders (Nurzhanovna, 2011). This, therefore, means that the Kazakhstan workforce demands education and training in textile manufacturing that might be provided by increasing FDI and its additional benefits, such as the transfer of technologies. Furthermore, the following reasons may have caused FDI in Kazakhstan's SEZs: (1) lack of efficient managers in majority companies; (2) failing (up to complete absence) of the business habitat (up to the criminalisation and executive subjection) in the provinces that determines high investment risks (Omarova, 2015). Likewise, Kazakhstan SEZs have a particular register of allowed/permitted activities. Current activities reflect target sectors and priority areas of government. The special juridical reign applies only when SEZ participants join in the priority performances identified for particular SEZ following the aims of creating the SEZ. If an SEZ member receives more than 10% of his income from any performance, which was not indicated for their SEZ, the member will lose all investment impetuses (CAREC, 2019). Hence, the particular register of SEZs restricts potential investors’ numbers, since not all performances of firms based on SEZs might be included.

As mentioned above, there are numerous causes for SEZs' inability to engage FDI as well as a lack of managerial experience, and majority investors rely on foreign labour to meet wants. Patently, due to these obstacles, the Kazakhstan government is interested in attracting experienced global firms to manage SEZs, as evidenced by the consulting work of DP World in the SEZ "Khorgos-East Gate" (CAREC, 2019). Nevertheless, apart from this one case, there was little progress in engaging private management firms to SEZs that can be considered as another problem of Kazakhstan SEZs. Also, analysis of the success and failure experiences of SEZs will have a vital aftermath for Kazakhstan economic liberalization and can be learned from international knowledge of SEZs activities.

2.3 Chapter summary

It follows from the preceding that the legislative framework has been created and updated for the functioning of SEZs in Kazakhstan. Despite the failure in the 90s that threaten the existence of SEZs, the Kazakhstan government has not stopped the process of creating such zones. Likewise, it established SEZs with a clear focus on a specific industry. However, according to the available data, the SEZs do not use their full potential in the development of the industrial clusters in Kazakhstan. Although the conditions for investment are the best among the CIS countries, there is no significant increase in attracting investment by SEZs, including FDI, and hence, their goals have not been achieved. Thus, currently, the great benefits of SEZs for Kazakhstan's economic and industrial development are not substantial. To study the international experience of the SEZ, the next chapter will examine in more detail the experience of China and South Korea. In addition, the lessons of the SEZ in China and South Korea will be studied in terms of their positive and negative impact on aspects of the national economy. The experience of leading countries in the development of industrial clusters with the SEZs will help to identify strengths and weaknesses for the further formation of a successful course in the development of the economy of Kazakhstan and, in particular, its diversification of industry using SEZs.

3.China and South Korea: analysis of SEZs activities in economic development

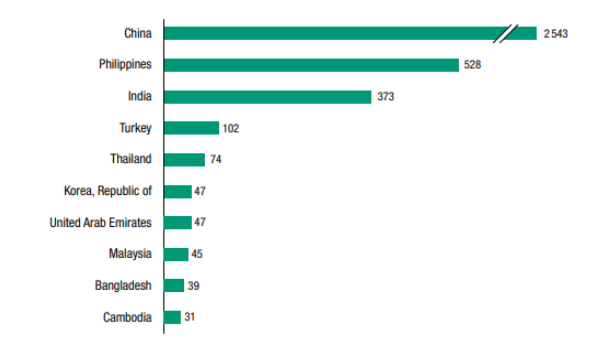

Although a general agreement on core aspects reflects the similarity of SEZ programs in the international political economy, there are majority differences in the purpose of establishing, regulation procedures, and economic consequences of different countries (CAREC, 2018). This chapter provides a brief history of SEZs and their role in economic development in two Asian states; China and South Korea. Moreover, it examines the performance of SEZs in both countries in terms of their crucial role in the structural reorganization of economy, facilitation, and engaging in the international market and advancing industrial development. Informatively, these two target countries are in the top 10 by the number of SEZs among developing Asian countries (Figure 1).

3.1 China

3.1.1 History of SEZs establishment in China

According to Hsueh (2012), various political views interpret how every state transforms using different priorities and measures. Domestic and sectoral differences in structural reform based on how each nation sees the strategic worth of sectors. China is the autocratic state that chased the aims of a sovereign country that represents the government's insight of strategic value to increase the advantages of liberalization (Hsueh, 2012). Deng Xiaoping was a Chinese leader who made the first essential measures to liberalise the communist-led economy in a country where a fifth of the world's population lives. The path that was determined by him directed the transformation of China from a closed outback into the market economy in two decades, which maintained development rates that were unparalleled in human history (Farole, 2011: 36; Harvey, 2007). The creation of SEZs in China was the first and most significant step that has done to structural reorganization and opens up its economy in 1979 (Farole, 2011). The creation of SEZs, their efficiency, and their influence on the transition time in China was discussed additional to related reforms and political questions. It has been argued that SEZs can perform as a legislative instrument in promoting trade and financial liberalisation, extending the use of assets, contribution to structural reforms, and economic development (Ge, 1999). Other SEZ programmes have not had such an influence at the national and international levels as the Chinese program (Farole, 2011). Its beginning was a core point in the evolution of modern SEZs. The first zones were created at the end of the 1970s as probation for the structural transformation of the whole economy by introducing capitalism and FDI beyond more than three decades of political and economic segregation. Initially created in the coastal regions of the country, the amount of SEZs expanded in the 80s and 90s of the 20th Century, covering a massive number of cities and areas, moving to the center of the country (Farole, 2011). This plan was victorious. China has become the largest exporter over the world of manufactured goods and a key receiver of FDI between developing economies. Furthermore, SEZs took a leading role during 1979-1995; the state attracted forty percent of global FDI in emerging countries. Ninety percent of them directed to shore regions (Farole, 2011) and SEZs contributed to the mutual side effect of technology and trade that served to build a thriving economy lengthwise the entire east coast of China (Eitzen, 2012). Nowadays, there are over 200 different types of zones in China, such as industrial, trade, technological zones. China gives an idea of more widespread use of SEZs as an instrument of economic development and universally expands its investing models in "zones of economic cooperation” (Lin & Wang, 2014).

The original goals of Chinese SEZs were comprehensive and without clearly determined preferences (Yuan & Eden, 1992). SEZs had to fulfill two tasks, such as attracting FDI and technology and connection with domestic firms. The practice of the Shenzhen SEZ illustrates the challenges associated with achieving these two different goals. For example, in the beginning, the zone was fully modeled as a trading and export center. Nevertheless, shortly after its formal foundation, the goals were expanded to establish a complex economic region, including industry, agriculture, livestock, trade, tourism, and real estate (Yuan & Eden, 1992). Moreover, for instance, the Chinese state compounded the performance of the Shenzhen SEZ by disclosure 14 shore towns for FDI as rivals, which reduced the possible investment level. Likewise, the location of SEZs in China can also interpret their inability to achieve their goals within a short period. In the beginning, SEZs were little cities without adequate infrastructure, roads, electricity, water supply, and communications needed for production (Yuan & Eden, 1992). One of the most serious obstacles that need to be removed in the economic sphere might be an improvement of infrastructure not only inside of SEZs but also the rest of the nation (Tatsuyuki, 2003). The development of social support will help achieve the goals of declining regional inequality by distributing benefits of growth to the internal provinces, as well as renew the obsolete industrial system.

3.1.2 SEZs performances in China

Given its impetuous economic development, China mainly owes to the showed effects that the most successful SEZs provide, which was the beginning of a lot of innovative strategies and processes that had a real revolutionary influence on the economic transformation (Yeung et al., 2009). The management and regulatory structure of Chinese SEZs allow the local authority to efficiently adjust and mediate SEZ processes by establishing and changing conditions for foreign and domestic investment (Chen, 1995: 596). SEZ functions are improving, versatile, and their targets often change during time. For example, first SEZs in emerging states generally had a typical selection of clearly defined and to some extent, restricted economic aims, which include attracting FDI, growing exports, and creating jobs. However, since the end of the 1970s, SEZs have expanded commercial objectives such as promoting the transfer of technology, managerial experience, improving ties with the domestic economy actors, and facilitation of broad regional improvement (Chen, 1995). As discussed earlier, SEZs provide a unique stimulus for its participants in terms of developing the economy. Simplistic business processes practice in SEZs and in those cases, when companies physically situated in zones are entitled to determined gains (Frattini & Prodi, 2013: 304). Nevertheless, the allurement of these benefits differs considerably in the process of time. For instance, if tax incentives affect economic performance, timely and reasonable correction of impetuses might stimulate more eligible financial actions of SEZs (Chen, 1995). Moreover, in a few emerging states, when the aims and roles of SEZs have shifted, the majority of the impetuses have been employed to districts outside SEZs because these benefits were more significant at the start of reforms in China (Chen, 1995). Thus, the close relationship among developing goals and stimulus describes the evolutional applicability of SEZs. Therefore, this evidence points out the necessity not to consider SEZs as separate facilities. Furthermore, they refer to want for a versatile treatment of changes in the functioning, planning, and development of SEZs, as well as their interaction with processes that develop outside the zones and the national policy of economic reforms.

In terms of separation from the prior dominance of the heavy industry, which was a primary for the growth in the Soviet era, the increasing of light production was devised as a way of becoming competitive with East Asian economies. China has benefited from its capability to transform the light industry into small manufacturing facilities and nanotechnology (Eitzen, 2012; Zeng, 2010). For example, Long & Zhang (2011: 7) cited a point made by Schmitz (1995) that one of the critical features of the industrial clusters noticed in China is the integrated manufacturing process which is divided into many small stages and which is carried out by the majority of small companies. By separating the manufacturing process into additional steps, the sizeable one-time investment might be converted into many small stages. For this reason, industrial clusters have become one of the most vital drivers of the rapid development of China (Frattini & Prodi, 2013; Zeng, 2010). The earlier SEZs mainly worked in traditional industries such as textile, leather goods, metal commodities, and furniture which were located in the provinces Guangdong and Zhejiang (Tatsuyuki, 2003; Wang & Yue, 2010), where historic trade possibilities, domestic manufacturing practices and government participation facilitated to very quick development of the area. Nevertheless, at the initial phase of SEZs, a considerable part of the investment was directed to the real estate, trade, and tourism sectors, while production still took a very insignificant role (Tatsuyuki, 2003). Focusing on light industry, common in East China, SEZs permitted for the supple reorganization, which sharply adapted to various stages of small scale trials. Inside a unified territorial cluster, the diversity of the domestic industry has rapidly turned into several particularised niches due to export increasing (Eitzen, 2012). For example, SEZs in the Tianjian region, which is a port area in the north-east of China, was created in the 1990s. By 2007, these earlier clusters for food production and medical facilities extended to six technological clusters: (1) electronic information in collaboration with Panasonic, Samsung and Motorola; (2) mechanical, electrical and optical integration; (3) biomedicine in cooperation with SmithKline Beecham and Novo Nordisk; (4) brand-new material cluster; (5) new energy and environmental cluster (Veolia Water and Vestas); (6) automobile cluster - Toyota (Eitzen, 2012). Since the opening up the Chinese economy, FDI in SEZs was mainly ventured in conjunction with external investors and domestic entrepreneurs (Tatsuyuki, 2003). Currently, impetuses for attracting investment in SEZs are significantly lower, as evidenced by the matter that foreign investors often choose to invest less or not to invest in Chinese SEZs than in other parts of the state (Zeng, 2010). Interesting to note, in the late 1980s, Chinese companies increasingly started to invest in SEZs to use various incentives (Tatsuyuki, 2003). For example, since 1997, the growth of Huawei Technology Co. Ltd, located in the Shenzhen SEZ, and other domestic companies, was a problem for transnational corporations (TNC) (Wei, 2000). Hence, the Chinese telecommunications equipment market has become the second biggest worldwide with huge market capacity after the United States. In the face of severe competition, equipment prices in China much less of the amount of similar equipment in other countries. This difference stems from competent research of cheap, hugely educated workforce, and not from low production costs due to majority TNC as well have manufacturing and trading chains in China (Wei, 2000). In addition, the Chinese SEZs need to increase efficiency by switching to high-tech, high-valued industries through research and development (R&D) sector (Tatsuyuki, 2003). The SEZs, which a catalytic role higher valued in the economic growth of China, might again act the same part in the new phase.

3.1.3 Success and failures of Chinese SEZs

Actually, one of the most successful SEZ in China is Shenzhen, which was able to increase the competitiveness of the Information and Communication Technology (ICT) cluster of private companies situated near the district with the endorsement of broad liberalisation and economic changes injected by the Chinese government (Leong, 2007). In 1982 guidelines were issued in the Shenzhen SEZ upon the segments in which FDI should be concentrated, which served as an apparent "signal" for foreign investors (Wei, 2000). Afterward, according to the help of a business-oriented government and continuously improving the economic environment, the capacity of investment in the production industry has begun to rise (Wei, 2000: 206). The most impressive progress reached by Shenzhen SEZ is the extension of industrial production and export. The fast pace of economic growth in Shenzhen SEZ has been obtained mainly due to the enormous capacity of increased shipping and FDI flows (Tatsuyuki, 2003: 11). Later, following a new growth plan of the Shenzhen SEZ, more attention was paid to the high-tech industry when selecting entrance to FDI to slowly upgrade the industrial pattern by moving from labor-intensive industry to technology industry (Tatsuyuki, 2003: 22). To move to high-tech and value-added market sectors, for instance, Huawei has made tremendous endeavors to hire many engineers whose average wages were nearly one-seventh of the average salaries in TNC. Then, in 1996, the largest R&D center was created in the telecommunications industry of China. Build on upgraded own products engineering competencies, Huawei had 70 percent of the market for broadband connection networks by 1998 that was specifically created to meet the needs of Chinese customers (Wei, 2000: 213). The effects of job creation caused by a sharp economic development and a massive influx of FDI into SEZs were very significant, and they were attended by inflation that caused a rapid increase in land prices, rents, and goods prices (Tatsuyuki, 2003). Per capita income in the SEZs as well grew significantly higher than the national average. Subsequently, robust regional income inequality has arisen among inner China and provinces with SEZs. At once, a growing number of economic and public offenses like illegal trade, corruption, smuggling, strikes, and environmental pollution also led to disagreements about the justified role of the SEZ (Tatsuyuki, 2003: 20). Negative sides of the performance of SEZs involve anxiety about often poor working conditions, limited surplus effects, and connections with domestic actors, their contribution to uneven growth of the national economy, and integration into the international market on which they are founded (Amirahmadi & Wu, 1995). Further, as Gopalakrishnan (2007) and Tatsuyuki (2003: 20) claim, a large number of the Chinese leadership and hardliner opposers blamed SEZs for adverse consequences. Although the zones have been successful with FDI and there are technological growths, they as well bear a negative side that is seldom admitted. Distressed migration, begging, and child labor all typical characteristics of SEZs and coastal areas of China. What happens in SEZs might be regarded as an improvement only concerning investments in total; in the social aspect, it is devolution (Gopalakrishnan, 2007). China made a few faults in the transformation process. For example, China’s keen desire for a sharp rise and industrialization was related to the growing income inequality between rural and urban areas and worsening social conditions (Lin and Wang, 2014). Nevertheless, Chinese SEZs established more significant particular goals of probation with market changes in price regulation, human resources management, financial practice, public administration, and social security (Chen, 1995). Since the time of receiving adverse effects, enormous efforts have been made to balance the Chinese economy in terms of reducing its dependence on export and investment; therefore, paying more consideration to quality of growth. One of the main concerns is about private participants. In China, there are currently six primary forms of public-private partnerships (PPP), each depicting increasing participation of private sector actors; hence, a gradual movement of risks from the government to the private sector. These include service treaties (management or services are transferred to outsourcing), acquiescence (which lead private capital to extend infrastructure and make the zone a valuable asset) as well alienation or privatization (Farole, 2011: 39). The participation of the domestic private actors in the improvement of infrastructure, transport, and services related to performances of SEZs might promote decreasing costs and increasing advantages.

3.2 South Korea

3.2.1 History of SEZs establishment in South Korea

Since the beginning 1960s, some of the Asian states decided to focus on their economic export programmes and EPZs were initially designed to act as a stimulant in the transition from domestic or traditional exports to non-traditional exports (Farole, 2011: 41; Byun & Wang, 1995). This growth pattern has led to the derivation of new East and Southeast Asia industrial states. South Korea was one of the major nations that followed this path (Farole, 2011). In the time of early industrialisation among 1962 and 1983, Korean politicians considered the development of new technologies by domestic companies as an essential aspect for modernisation of industry (Amsden, 1992; Chang, 1993). For them, this signified robust government monitoring over FDI. Korean politicians chose foreign loans, which guaranteed by the state, to FDI in terms of filling the constant gap in savings. Even while FDI was permitted, external majority ownership was prohibited, with a few rare exceptions outside the FTZ (Chang, 1993). Similarly, priority technology licensing was subject to severe restrictions whenever it was possible. For instance, technology licensing was prohibited in industrial sectors where domestic technological abilities were considered promising (Chang, 1993). Thus, South Korea created its first SEZ in 1970 in Masan, where it permitted merely FDI. In addition, South Korea adopted SEZs under politically isolated reigns and in the primary phases of the development of the economy (Aggarwal, 2012: 877; Byun & Wang, 1995; Tatsuyuki, 2003: 8; Warr, 1989). The Masan EPZ achievement inspired the South Korean government to build another zone in Iri on the west coast in 1973. Since the 1990s, the governments of South Korea started a forceful contribution to the globalisation of the domestic economy, in particular beyond the 1997 financial crisis. Likewise, the government sharply shifted its political position to FDI and moved from a protectionist and nationalist approach to liberalisation (Park, 2005; Byun & Wang, 1995). However, it was very difficult given the political and social barriers such as the resistance from chaebols (big Korean corporations), policymakers and labor unions to neoliberal approach (Chang, 1993; Park, 2005) Considering this situation, the South Korean state resolved to evolve SEZs in which more decisive measures for deregulation and liberalisation were to be taken (Park, 2005: 864). Thereby, Korean politicians made a compromise and adopted the path of elective liberalisation due to its more permissible reforms than broader liberalisation on the national level.

In Korea by 2000, there were solely two SEZs, and the same year, the enlargement of SEZs number has started. In this time of late industrialisation, South Korea developed the conception of SEZs in 2002 to attract more FDI, especially in R&D and services fields (Aggarwal, 2012: 881; Park, 2005). In contradistinction to conventional SEZs, created at the primary stage, which was closed industrial zones, modern South Korean SEZs are metropolitan industrial towns located on many square kilometers. It is also Interesting to note, according to Aggarwal (2012) and Yuan & Eden (1992: 1036), modern SEZs in South Korea were established on the model of the Chinese SEZs, while Tatsuyuki (2003) pointed out that the achievements of first EPZs and free port towns in South Korea and the rest of Asian tigers states seem to have served as an example for creating Chinese SEZs. According to the authors, the aim of creating this new kind of SEZ was to turn the state into a logistics, business, and financial center of Northeast Asia. In addition to becoming a testing ground designed to help regenerate a weak internal economy. Similarly, in 2003, the Committee and the Planning Bureau of SEZs were established to support them. Modern SEZs engage economic practices with high added value, such as trade, services, and manufacturing. Nowadays, they are considered outstanding towns with contemporary ports, offices, and airports likewise, prime hospitals, financial services, schools, shopping centers, tourist facilities, and leisure services (Aggarwal, 2012: 882).

3.2.2 SEZs performances in South Korea

Since the beginning 1960s, EPZs were launched while Asian countries, in particular, South Korea has stepped up their attempts to manufacture light industrial commodities to the external market (Tatsuyuki, 2003: 6). In South Korean SEZs, there are two predominant industrial sectors: textiles and electronics (Jayanthakumaran, 2003). Meantime, South Korea is the state that has been able to conduct the process of earlier industrialization most speedily compared to other countries (Yoo, 1997). Stress on the export increasing view of South Korea was accompanied by welcomed FDI and new relationships with foreign customers in the era of globalization and neoliberalism. FDI and subcontractors have supported to ease the balance of payments troubles, provided technology, and opened upmarket tracts needed for external development policy (Amirahmadi & Wu, 1995; Byun & Wang, 1995; Jayanthakumaran, 2003). Nevertheless, foreign investors were invited to input in the light industry export part, while they were not advised to invest in import-substituting parts due to their protectionist policy (Byun & Wang, 1995; Yuan & Eden, 1992). On the one hand, according to Johansson (1994), the neoclassical pattern did not take into account the side effects of FDI in SEZs and asserted new literature on growth theory. As he claims, the detached nature of SEZs and the low-skilled manufacturing operation do not contribute to the transfer of technology and related external effects. Nevertheless, South Korea's boom was built on a concept of economic improvement that covered much more than just the technology transfer. The development concept is a complex issue, including such broad areas as setting durable goals for increasing and structural reforms, investing in production capacities and infrastructure, ensuring qualified workforce, as well as technological development with SEZs (Chang, 1993). For instance, one of the most successful cases that reflect the role of FDI in technology transfer is the Masan EPZ. The goal of establishing the Masan EPZ was to boost productivity growth of the light industry by attracting FDI that supplemented the national economy but did not rival with them (Tatsuyuki, 2003: 9; Warr, 1984). The Masan EPZ proposed favorable operating and investment climate for respective investors include gorgeous infrastructure and prime industrial parkland with reliable governance and endorsement services in the technological industry. The zone has reached one of its most important goals to serve as an accelerator for diversification of the economy by creating competitive industrial clusters. Later in 2000, the Masan EPZ was rebuilt to represent liberalised external and internal economic surroundings. At the primary phases of increase, SEZs are used as analytical instruments for modernising the economy. Then over time, their role decreases with the development of production. Nevertheless, they proceed to increase the influx of foreign exchange and provide the diversification of the national economy. As Madani (1999) claims, EPZs are an inalienable section of future economic changes, especially diversification of industry. In this view, EPZs should have a defined life expectancy, losing their importance as states pursue regular macroeconomic reforms. As far as the state's economy opens up and develops its opportunities for the competitiveness of industrial export, EPZ export and employment proportion in total export and employment rates declines (Madani, 1999: 17). For example, South Korean SEZs fall into this rank because, as mentioned earlier, the government created them in early and late industrialisation periods due to global market changes as well as internal financial problems such as the constant gap in savings. It means that SEZs as a tool of economic reforms can be useful at the different stages of industrial evolution.

South Korean politicians have reintroduced an old concept of SEZs due to globalisation processes around the world, which widely proposed that moving from a production country to a service-oriented country demands the creation of global hubs for the international capital, technology, goods and skilled labor in the national terrain (Park, 2005: 852). According to the author, these hubs' role might be performed by SEZs. Currently, new types of SEZs appeared in South Korea. As these SEZs are still in their inception, South Korea estimates and adjusts its intervention policy to procure their achievement (Aggarwal, 2012). Such varied types of SEZs implicate that they might be tailored to the actual wants, circumstances, and goals of emerging states (Amirahmadi & Wu, 1995). For instance, in July 2019 the Minister of Small and Medium Business and Startups of South Korea said: "As there is no sky for a bird locked in a cage, there is no innovation if locked in a regulation", announcing the description of seven latest South Korean SEZ that are regulation-free for the first time on the earth (Invest Korea, 2019). It demonstrated the resoluteness of the South Korean state to build a pliable enterprise climate following the wave of the fourth industrial revolution. Regulatory-free SEZs are territories created to enable companies to handle business efficiently, without limitations from adjustments, to test innovative technologies, and to encourage innovative companies through endorsement steps like R&D financing and tax incentives (Invest Korea, 2019). These non-regulatory SEZs are listed below: Busan, Gangwon-don Province, Sejong City, Daegu Capital City, North Gyeongsang Province, North Chuncheon Province, and South Cholla Province. In each province and town was defined a specific industry such as (1) the bio-health industry; (2) blockchain technology zone; (3) a self-driving zone with the goal of creating the center of South Korea's first commercialisation of autonomous vehicles (4) a disposal area for next-generation batteries; (5) a well-being area, for example, one of the goals of that is a creating the world's first joint medical devices manufactories using 3D printers; (6) zone for electric mobility (e-mobility). E-mobility is a personal vehicle using electricity; (7) a non-regulatory zone for intelligent security management to develop a standard for wireless control, alarm system management, and safe gas shutdown (Invest Korea, 2019). Taking the first step into the future, the South Korean state is preparing to service these new SEZs, which are a testing ground for manufacturing innovations. This example also illustrates that SEZs can be a useful tool for diversification of the national economy to develop industrial clusters.

3.2.3 Success and failures of SEZs in South Korea

As Jayanthakumaran (2003: 58) points out, companies of South Korean EPZs have affiliated with the domestic economy over subcontracting, and local procurement then has achieved positive results in increasing export following liberalisation processes. Consequently, the correlation of export in EPZs to all production export, as well as FDI in EPZs to all FDI, was significant in the 1980s. Likewise, Jayanthakumaran (2003) and Yuan & Eden (1992) depict an outstanding relationship between EPZs and the domestic market in South Korea in terms of buying local resources and services like finance, insurance, transport, and packaging. For example, the highest domestic purchases have exhibited on footwear production. In 1971, enterprises in SEZs used merely 3 percent of manufacturing components from South Korea. Comparatively, 45 percent of details were received from South Korea by 1990 (Aggarwal, 2012; Byun and Wang, 1995; Tatsuyuki, 2003). Moreover, the subcontracts were exclusively significant compared to SEZs of other Asian states (Jayanthakumaran, 2003). Thus, local companies expected to gain admission to the technical know-how of the industry. Furthermore, in 1974, the South Korean state-permitted outsourcing of manufacturing operation from the Masan EPZ, which was due to the matter that the zone was engaged and companies had problems with extending their bulk (Aggarwal, 2012). Outsourcing has confirmed usefulness for the growth and technological renewal of companies placed beyond SEZs. The state also permitted 100% of local trading in all industrial sectors except technologies in 1980, where merely 5% of trade might be realized internally (Aggarwal, 2012). This instantly brings to rise in internal merchant to 14.7% in 1981, growing to 36% in 1990. Thus, SEZs performance a core part in challenging and innovating practices in the national economy. As described earlier, South Korea was a market economy, which accepted the export-oriented approach that offered an attractive stimulus for foreign investors. The state of South Korea also has a coherent and focused policy aligned at increasing the endowment to the rise of FDI in SEZs (Yuan & Eden, 1992). Nevertheless, according to Aggarwal (2012) and Byun & Wang (1995), industrial SEZs in South Korea still dominated by domestic investment; the FDI level is low there. Whereas the Masan SEZ is merely one zone that attracts significant FDI, the amount of FDI in other SEZs is minor. Besides, among the SEZs created after 2000, only two Daebul and Gunsan managed to attract investment, the others could not (Aggarwal, 2012: 888). The main problems facing SEZs are the high worth of territory, a lethargic approval practice, burdensome bureaucratic processes, unsatisfactory impetuses, and restrictive rules regarding FDI, South Korea's image as a closed economy, and fierce rivalry from China (Aggarwal, 2012; Bune & Wang, 1995). Afterward, the South Korean state took a number of remedies to strengthen SEZs such as (1) extending the term of tax incentives; (2) removing restraints on FDI in SEZs; (3) delegating authority to provincial heads and mayors of municipalities to provide permission for improvement factories to decline bureaucracy; (3) allowing foreign investors to inlay in internal medical entrepreneurship; (4) weakening immigration rules for investors involved in the development of research centers and logistics; (5) facilitating the process of issuing visas to employees who will work for foreign companies in SEZs (Aggarwal, 2012: 890).

3.3 Chapter summary

The success or failure of SEZs as an economic development instrument can be the result of three policies, such as structural economic reforms, facilitation entering the global market, and advancing industrial development. For instance, China's economic growth was dramatic since they started open-door reforms. The transformation of China into a market economy has accelerated due to the success achieved in SEZs (Tatsuyuki, 2003). The SEZ was almost a vital tool in implementing these politics and an unprecedented experiment in revitalising the economy by introducing neoliberal aspects into the Chinese socialist economy. In addition, the performance of South Korea SEZs was outstanding in economic and industrial development, as well. The success of South Korean SEZs seems like a mix between external and internal processes such as attracting FDI for learning its benefits with focused and clear policies (Yuan & Eden, 1992) and buying local components for manufacturing and permission outsourcing of production, through the implementation of liberalisation and protectionism policies together. Thus, the South Korean government produced a compromise and chose the path of selective liberalisation. The next chapter is the conclusion indicating the results acquired. This chapter will summarise the empirical experiences of SEZs in case study countries and present specific recommendations for further possible adoption of their effectiveness by Kazakhstan. Furthermore, it illustrates the future focus of research on the field of the development of SEZs.

4. Conclusion

4.1 Concluding remarks

In this examination, a stronger comparative analysis of SEZs in Kazakhstan, China, and South Korea was not possible because of the lack of a reliable and sequential database. However, these three countries represent the different development paths and activities of SEZs. Although at present there are no significant efficiencies of SEZs in development of Kazakhstan economy and their goals have not been achieved, it concludes that the SEZs can play a substantial role for Kazakhstan economic development, especially in the diversification of industry, as well as they performed in China and South Korea. Moreover, as global experience in the era of neoliberalism shows, the creation of SEZs was a driving factor in increasing the industrial cluster (Zeng, 2010). In these three countries, there are majority differences in the purpose of establishing regulation procedures and hence, in economic consequences. This thesis examined the performances of SEZs as a core tool for economic development and diversification of industry. In the international political economy existed a lot of cases of successful SEZs performances in influencing integration in the global market, structural reorganisation of economies, and increasing investment. Meanwhile, they face the problems related to investment climate and a complex production process as well as other issues arising with the rapid pace of the fourth industrial revolution. As seen from the review, SEZs in Kazakhstan might be a catalyst for economic reforms because there are excellent government involvement, developed infrastructures, but if they will subject to increase their effectiveness. Kazakhstan SEZs are in a favorable place to learn from the experience of SEZs in China and South Korea, despite the various circumstances and limitations, they can learn from fails and successes. For instance, In terms of secession from the former domination of the heavy industry, which was observed for Chinese growth in the Soviet-era communism, the development of light industry was considered as a way to become competitive with growing East Asian states. China has won from its ability to turn the light industry into small production facilities and nanotechnology (Eitzen, 2012). The transition to the light industry was the issue that China faced, which SEZs in South Korea met during the 1980s when moving to a high value-added industrial structure with an emphasis on the high-tech industry. Thus, South Korean and China went through two stages of industrial changes in the broad timeframe, while Kazakhstan can learn from its reforms at once. However, Kazakhstan must be scrupulous, while taking the experience of other countries, to prevent the faults, which experienced by SEZs. Moreover, the worth of SEZs should be determined to take into account much contemplation as well.

Firstly, all three case study countries created first SEZs on a small scale, but for various reasons. While, Chinese SEZs were built on a small scale to experiment with aspects of liberalisation to identify negatives before spreading across the whole socialist country, SEZs in South Korea, as well as in Kazakhstan, were established on the small-scale in order to attract FDI according to neoliberal market circumstances, which were necessary in the era of globalisation. Moreover, the South Korean government could not realise this at the national level due to the confrontations of local entrepreneurs, politicians, and labour unions. Thus, as a result of experiments with SEZs, the Chinese economy could join the international market, and the South Korean government attract FDI. Consequently, Kazakhstan SEZs can use the institutional policies for SEZs of both China and South Korea due to its aims to join to the international market and attract FDI, and make structural reforms according to its industrialization programme. Secondly, all three countries adopted SEZs strategies at different times. China and South Korea have reached marvelous success to their SEZs influence on primarily stage industrial development. Then, South Korea and China have shifted to the next stage of evolution in their SEZs. China reregulates SEZs to develop high technology industries, while South Korea attracts FDI through SEZs, seeking to establish world-class towns with regional firms, financial, and logistic centres due to challenges of a fourth industrial revolution. In order to avoid new problems related to the fourth industrial revolution, Kazakhstan SEZs might anticipate in advance trends in their target sectors and adapt changes. With clearly defined goals, host states might also understand that most zones never develop as planned.

Furthermore, nowadays, indifference from the past world SEZ experiences, the adoption of the best managerial, environmental, and social standards by SEZs attract as a competitive advantage. For example, the main attractive power of China was its certainly low wages, combined with differences stimulus. The comparative advantage of little workforce cost is declining due to economic growth. Thanks to significant investments, SEZs also leads to increasing employment and salaries Thirdly, as analysis illustrated, SEZs play a vital role in the economic development of emerging states if they are created at their suitable phase of economic growth. Their influence is probably to be very outstanding at the beginning of the transformation from domestic to international strategies. The SEZs might not only contribute to an export rise but as well as maintain as an experimental platform for new policies. Moreover, they can promote the passage from a protected economy to the market. However, SEZs significance has a downward trend when emerging states shift to liberal trading and investment mode (Amirahmadi & Wu, 1995). For this reason, China and South Korea turned their attention to the high-tech development industry, which has a lot of challenges, such as attracting highly qualified engineers, managers, and knowledge in this field. Then, to solve these issues by creating R&D centers. The government’s participation in establishing R&D centers with universities and capabilities for the training of labor forces was vital for shifting to the high-tech industry in these countries. Moreover, the role of states in creating more effective maintenance and dissemination systems of technology is as well, extraordinary. The Kazakhstan SEZs may adopt these practices in terms of the development of a high-tech industry due to the challenges of the fourth industrial revolution. In addition, they can create particular politics and benefits in order to contribute to attracting scientists, researchers and technical personnel to these areas for the development of domestic R&D centres as China and South Korea, which gave a range of stimulus for attracting engineers and qualified managers, while Kazakhstan met a problem with engaging experienced managers. Fourthly, the paper uses the data to investigate the influence of SEZs on the domestic economy as well. Comparing with the empirical evidence between SEZs in China and South Korea, it was found that the SEZ agenda boost FDI and does not extrude domestic investment. In opposite, the increasing domestic investment promoted the effectiveness of SEZs in both states. China and South Korea have increased domestic investment in SEZs that are encouraged and receive the same privileges as foreign investors, while Kazakhstan has a low level of any investment. Moreover, South Korea enhanced the subcontracts, which were exceptionally significant compared to the SEZs of other Asian states (Jayanthakumaran, 2003). Later, China also increased ties with local firms and involved domestic investment; as a result, it received advantages. Besides, domestic entrepreneurs expected to gain access to the technical know-how of the industries that could facilitate broad regional improvement. However, in China and South Korea, primarily SEZs were established by governments for the development of industrial clusters by attracting FDI in terms of their help to provide technology and service transfer and skills training (Chang, 1993).