Analyzing Questionnaire Survey Responses from Accounting Stakeholders

Chapter 6: Questionnaire Survey Analysis

6.1 Introduction

The main aim of this chapter is to illustrate the analysis of the questionnaire surveys, which has been collected from the three key-targeted stakeholders namely: accounting academics, professional trainers and preparers of financial statements. In accordance with the methodology, a quantitative method employed in order to report the analysis of the data collected from the questionnaire surveys. As discussed earlier in Chapter 5 of this thesis, mixed-method approach including questionnaires and interviews has been adopted, while the current chapter reflects the findings from the questionnaire survey. This section focuses specifically on quantitative dissertation help related to data analysis techniques and interpretation.

This chapter comprises six main sections. Section 6.2 discusses the development and the processes underpinning questionnaire surveys. Section 6.3.1 summarises the background information about the respondent groups. Section 6.3.2 presents an overview of the nature of education and training associated with IFRS in Saudi Arabia. Section 6.3.3 reports the results of an analysis of the effectiveness on the same matter. Section 6.3.4 discusses the institutional factors affecting IFRS education and training. Section 6.4 draws the conclusion from the questionnaire analysis.

6.2 The Development and the Process of the Questionnaire

This section provides an overview of the development of the questionnaire surveys. Five main steps were undertaken in order to collect the data that will attempt to answer the main research questions addressed by this thesis. These steps will be discussed in turn, below.

6.2.1 Questionnaire Design

First, the researcher designed three English-language versions of the questionnaire based on a review of the literature, taken under consideration the main aim of this study which examines the education and training associated with the implementation of IFRS in Saudi Arabia.

Continue your journey with our comprehensive guide to Analyzing Exercise in Obese Older Adults.

Take a deeper dive into Accounting with our additional resources.

The questionnaire surveys are broadly similar, but some sections included amended questions based on the participants’ specific role and their involvement with IFRS education. All the questionnaires were divided into five main sections, namely: (i) demographics and background details of the participants (e.g. gender, age, nationality, level of education, experience, etc.); (ii) the nature of education and training associated with IFRS in Saudi Arabia; (iii) the effectiveness of education and training associated with IFRS; (iv) the institutional factors affecting education and training associated with IFRS; and (v) concluding questions. In accordance with the latter section, there is an optional question asking the participants, if they are willing to be contacted later on for an interview. This is a key step employed to identify further interviewees for the second method of the mixed-method of this research which is the interview guides.

Take a deeper dive into Accounting Role with our additional resources.

6.2.1.1 Type of Questions

The questionnaires include primarily closed-ended questions in order to help the participants to navigate the survey questionnaires more easily and to aid the researcher in capturing the dataset. Thus, they attempt to answer the main research questions as follows: (i) to ascertain the nature of education and training associated with IFRS in Saudi Arabia and evaluate its effectiveness; and (ii) to identify the factors affecting education and training associated with IFRS. Under the closed-ended questions, the researcher attempted to use three main types of questions, namely: (i) multiple choice; (ii) checklist; and (iii) Likert scales in order to encourage the participants to complete the questionnaire. This approach is in line with similar studies that have employed questionnaires in accounting and finance research (Gray and Roberts, 1984; Jermakowicz and Hayes, 2011; Prewitt and Morris et al., 2013; Alshekmubarak, 2015; Loyeung et al., 2016; Alamoudi, 2016; Pawsey, 2017; Yamani and Almasarwah, 2019; Albu et al., 2020).

Looking for further insights on Thematic Analysis in Exploring Friendship? Click here.

6.2.1.2 Piloting

English-language versions of the three questionnaires were piloted. As De Vaus (2013) suggested, a pilot test is useful to assess: (i) the reliability and validity of the questionnaire; (ii) the terminologies used; (iii) the sequences and types of the questions; (iv) formatting the questionnaire; (v) the estimated time is taken to complete the questionnaire; (vi) the clarity of the questions; and (vii) capturing some language errors. Therefore, the researcher decided to pilot the English versions of the questionnaire across several accounting academics, professional trainers, and preparers. The questionnaire related to the accounting academics was sent to three academies in Saudi Arabia. Two copies of the questionnaire were returned with the following feedback: (i) some statements required further clarification; (ii) language errors; and (iii) adding or adjusting some questions. In terms of the professional trainers, five copies have been sent and four were returned with the following comments: (i) asking for more explanations with regard to cultural factors; and (ii) adding a question under the educational factor. For the preparers, six pilot copies were sent and five were returned with the following feedback: (i) suggested amending the potential time taken to complete the questionnaire from 10 to 15 minutes; (ii) recommended that the invitation letter should be made more attractive to encourage more respondents and to increase the response rates; and (iii) issues with sentence structure and grammar. The researcher considered the feedback and made amendments accordingly.

Continue your exploration of An Open And Closed Ended Questionnaire On Various with our related content.

6.2.2 Translations

Second, the researcher translated the questionnaire into the Arabic language because the majority of the participants across the three-targeted groups are Arabs and the Arabic is the official language, used in their business. Another reason for translating the questionnaires was that, the participants were likely to have a greater interaction and understanding of the questions being asked and were thus more likely to provide clear and considered answers. The translation went through more than one stage in order to minimise any problems. First, the researcher translated each statement into Arabic and asked for a review from academic colleagues whose native language is the Arabic. Second, a copy of the three versions of the questionnaire (the English-Arabic version) was sent to an English teacher who is fluent in both English and Arabic to review language accuracy and ensure the Arabic versions were consistent with the English versions. Lastly, a copy of the three Arabic versions of the questionnaire was sent by email to an accounting academic, a professional trainer, and a preparer to guarantee that the questions were clear and understandable for the targeted participants. After completion of the translation processes, the researcher was required to make some alterations in order to improve the Arabic versions and the final translated questionnaire for distribution. The final versions of the English and Arabic questionnaire are provided in Appendices 6.3 to 6.8.

6.2.3 Distribution

Third, the Arabic version of the questionnaire was distributed to the three targeted groups: (i) accounting academics; (ii) professional trainers; and (iii) preparers of the financial statements, via an electronic official survey tool provided by the University of Dundee called Bristol Online Survey, “BOS”. The email addresses of the participants were available via official public websites. Consequently, the researcher sent a specific link for each targeted group to their email address. The links contained an information sheet, which mainly informed the participants about the nature of the study, the confidentiality of the given information and the way where to be stored. Samples are provided in Appendix 6.2.

6.2.4 Collection

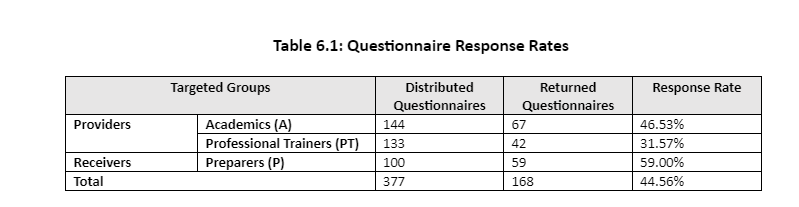

Fourth, the researcher collected the raw questionnaire data from the online survey tool “BOS” adopted in this study. Table 6.1 below summarises the targeted groups, the number of distributed questionnaires, returned questionnaires and the response rate. It indicates that, 377 copies of the questionnaire were sent and 168 were received. The total response rate is 44.56%, which further represents 46.53% of the accounting academics, 31.57% of the professional trainers, and 59% of the preparers of the financial statements.

This total response rate of 44.56% seems to be reasonable due to the trending nature of IFRS in Saudi Arabia, which is a key player in achieving the Saudi Vision 2030 by generating the benefits of increasing foreign direct investments and enhancing the relations between Saudi markets and international markets (Nurunnabi, 2020). In comparing this response rate with other studies, a total response rate of greater than 40% is common in studies associated with IFRS adoption and IFRS education in Saudi Arabia. For example, Albader (2015) employed online questionnaires and his total response rate was 52%, while Alkhtani (2010) used the same method and recorded a total response rate of 40%.On the other hand, some studies conducted in Saudi Arabia, the accounting literature on non-IFRS topics recorded lower response rates. For instance, Alamri (2014) examined corporate governance in Saudi Arabia using online questionnaires and he obtained an overall response rate of only 9%. Another study by Alamoudi (2016) on corporate social disclosure in Saudi Arabia recorded a total response rate of less than 20%.

Dig deeper into Academic Integrity in Higher Education with our selection of articles.

In this study, one academic and one preparer out of the 168 responses were excluded due to the incompleteness of their surveys. Thus, the final sample is a total of 166 (44.03%) respondents, who completed the questionnaires across the three targeted groups. According to the literature, excluding questionnaires is common in quantitative research and there are arguments regarding the allowable exclusion rate of the questionnaire surveys (Bennett, 2001; Enders, 2003). For example, Bennett (2001) argued that, excluding questionnaires should be up to 10%, while Enders (2003) emphasised that, the maximum allowance for the questionnaires should not exceed more than 15% of the total responses rate.

The limitation of this method is that the researcher distributed the questionnaires only in the Arabic language, which may create a problem of nonresponsive bias. This is because there is a minority of non-Arabic speakers amongst accounting academics, professional trainers, and preparers working in Saudi Arabia who did not take part in the study due to the surveys being distributed in Arabic; yet these members of the population may have some reasonable views on IFRS education.

6.2.5 Analysis

The analysis is the final phase of the questionnaire survey process. The online survey tool “BOS” adopted in this study helped the researcher to export the surveys data into the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS). The data transferred from BOS to SPSS were in a coded format. In addition, the researcher checked the SPSS files in order to ensure the variables names, values, and level of measurements was consistent in order to run a valid analysis. The researcher used non-parametric tests because the majority of the questions that covered the main research questions were based on a five-point Likert scale. The two common non-parametric tests, which could help to analyse the Likert scale questions, are Kruskal-Wallis (K-W) and Mann-Whitney (M-W). They used to identify if there are significant differences between two or more groups of an independent variable based on the ordinal level of measurement (Anderson et al., 2009). In this study, the Kruskal-Wallis (K-W) test was used to compare between the means of the three groups while the Mann-Whitney (M-W) test was utilised to compare between the means of the two groups (Couch et al., 2019).

6.2.5.1 Reliability and Validity

Ensuring the reliability and validity of the research instrument is a key part of the questionnaire surveys analysis process. Reliability is described as an approach to evaluate the quality of the data collected (Bryman et al., 2018). It is also an important tool to measure the internal consistency of questionnaire results and the Cronbach alpha test is the most commonly used to measure this (Field, 2013). Cronbach alpha analysis has values from zero to one, where a value closer to one indicates that, the results are more reliable (Bryman et al., 2018). However, values below 0.60 make doubts on the reliability of the research instrument used. In the meantime, values above 0.90 demonstrate an excellent internal consistency in the questionnaire results while a value above 0.80 indicates a good internal consistency of the results of the survey (Field, 2013). In the case of this present study, the reliability test was adopted using Cronbach’s alpha test for the Likert scale questions. It showed values are between 0.80 and 0.90 and this further indicated a good internal consistency of the dataset collected. This provides some comfort to readers that the results reported and interpreted in this study are reliable.

Validity means that, the instruments “measure the concepts what is intended to be measured” (Greener, 2018, p.375). In other words, researchers should measure what they need to be measured. Focusing on content validity is highly recommended before distributing surveys, as it assesses the content of the questionnaire and ensures that the questions are cleared and validated (Taherdoost, 2016). A number of important steps should be considered in order to assure the validity of the questionnaire as follows: (i) reviewing the validated questions adopted in previous questionnaires from prior studies; and (ii) piloting the questionnaires (Taherdoost, 2016). This study used both steps in order to guarantee the validity of the questionnaire and the participants who involved in the pilot study recommended potential alterations (see more in section 6.2.1). Thus, the researcher attempted to adopt these two steps in order to ensure that questionnaires were reasonably valid.

6.3 Results

6.3.1 The Respondents’ Background

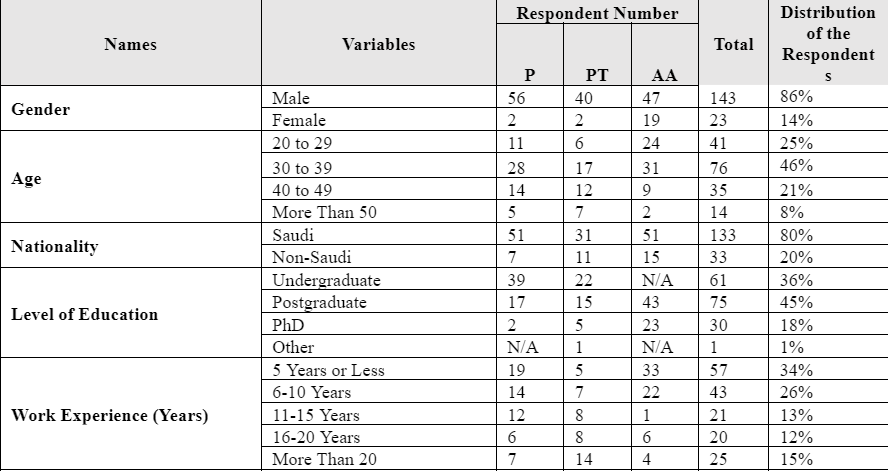

Table 6.2 summarises the background information for all respondents. As reveals from the data supplied in Table 6.2 that143 (86%) of the respondents were male and 23 (14%) were female. Thus, gaining access to females’ respondents was difficult due to the social structure of the governmental system in which male and female workplaces are separated (Albader, 2015).The Table 6.2 also demonstrates the age distinguish of the respondents (from 20 years old to more than 50 years old), which further indicated a different range of ideas and experiences from these respondents with regard to IFRS education. In addition, the inspection of Table 6.2 reports that 133 (80%) of the respondents were Saudi nationals and 33 (20%) were non-Saudi. It can be noted that the majority were Saudi nationals. This can be interpreted by the fact that in 2016, Saudi Arabia announced a plan called the Saudi nationalisation scheme ‘Saudisation’ or ‘Nitaqat scheme’. This plan is part of the Saudi Vision 2030 and it aims to “enhance the effectiveness of ‘Saudisation’ policy so as to reduce the level of unemployment among youth in the Kingdom” (Sadi, 2013, p. 39). In other words, this scheme attempts to fill positions in both the government and private sectors with Saudi nationals in order to reduce the unemployment percentage in the country (Ministry of Labour, 2019).

With respect to the level of education, 36% of the respondents held undergraduate; 45% postgraduate degrees and 18% possessed PhDs.Thus, the sample of this study has a greater total percentage of postgraduate and PhD holders as compared to those with only a first degree, which suggests a reasonable knowledge and experience in IFRS education. In terms to the work experience of the participants, an inspection of Table 6.2 indicates that 5 out of 42 (12%) professional trainers had five years’ experience or less, while19 out of 58 (33%) preparers possessed the same range of work experience. However, the percentage is considered to be high, in the case of the accounting academics group, 33 out of 66 (50%) of whom had up to five years of teaching experience. This low of teaching experiences among the accounting academics can be explained by the fact that, a high number of those academics are greatly involved in administrative responsibilities (Srdar, 2019).

Continue your exploration of Analyzing Exercise in Obese Older Adults with our related content.

- 3. All the respondents from the accounting academics (AA) group hold a postgraduate degrees or PhDs. With respect to their positions, the results indicated that 43 out of 66 (65%) are lecturers, 18 out of 66 (27%) are assistant professors, and 5 out of 66 (8%) are associate professors. This sample has a large respondent rate from lecturers which represent (65%) of the total AA. In comparing this result with other studies in the context of Saudi Arabia, Mallak (2018) found that the majority of his participants were lecturers. This also supported by the Ministry of Education which reported that a large percentage of lecturers in Saudi Arabia still existed (MOE, 2020).

In terms of professional qualifications, 59 out of 166 (36%) respondents had various professional accounting qualifications. For example, 33 out of 59 (56%) held CPAs, SOCPAs, or both, while 107 out of 166 (64%) had no accounting professional qualification at all. A high percentage of those without accounting professional qualifications come from the accounting academics group. As reveals in Table 6.2 that 58 out of 107 (54%) did not hold professional accounting qualifications comparing with other groups. However, the representation of qualified accountants in this study was reasonable, as the total number of those who have obtained a professional accounting qualification in Saudi Arabia generally considered to be very low, as the findings from the interviews reported that the number of CPAs in Saudi Arabia was insufficient to meet the labour markets and the companies’ needs (see more in section 7.8.1.1).

In terms of companies, organisations, and university types, 30 out of 58 (52%) individuals work in the financial sectors. This is followed by 24 out of 58 (41%), who worked in non-financial. On the other hand, only 7% worked for other sectors. Half of the professional trainers (50%) worked in local accounting offices and the remaining half in accounting professional bodies and other similar organisations. All the accounting academics who participated in this study teach in public universities. Thereby, no accounting academics from private universities have taken part in this study due to the lower number of private universities in Saudi Arabia. There are 31 universities teach accounting programmes and only three of those are private universities (SOCPA, 2019). Thus, it is acknowledged that, a lack of representations from the private universities could be seen as a limitation of the current analysis. However, the representatives from the majority of large universities in Saudi Arabia took part in this study.

- 4. In terms of the other professional accounting qualifications: two respondents have ACCA/FCCA and other two hold CERTIFRs. However, the remaining 22 out of 59 (37%) have different accounting qualifications such as Certified Management Accountant (CMA), Certified Internal Audit (CIA), Certified Islamic Professional Accountant (CIPA), and Certified Fraud Examiner (CFE).

According to Table 6.2,111 out of 166 (67%) of the respondents agreed that, Arabic is the official language, used in their work. Meanwhile, 55 out of 166 (33%) used, English as the official language. In terms of the level of familiarity and unfamiliarity with the use of IFRS among all the respondents, 138 out of 166 (83%) were familiar and only 28 out of 166 (17%) were unfamiliar. This indicates that the majority have some level of knowledge in IFRS. In addition, the analysis of the results in Table 6.2, reveals that, the professional trainers group had the lowest level of unfamiliarity with only 3 out of 28 (11%), while the preparers’ group had the highest level of unfamiliarity which 14 out of 28 (50%) were unfamiliar among the three participant groups. However, a reasonable sample from the total number of preparers which 44 out of 58 (75%) were familiar with the use of IFRS in the country.

Table 6.2: Background of the Respondents

6.3.2 The Nature of education and training associated with IFRS in Saudi Arabia

This section analyses the answers of the preparers of financial statements, accounting academics and professional trainers to the questions associated with the nature of education and training associated with IFRS. It begins by analysing the responses of the preparers in terms of: (i) who provided IFRS education and training; (ii) to what extent do the preparers receive education and training; (iii) what teaching methods are used; (iv) the duration of IFRS courses; (v) the cost of education and training; (vi) where the training courses take place; and (vii) what encourages preparers to attend the training.

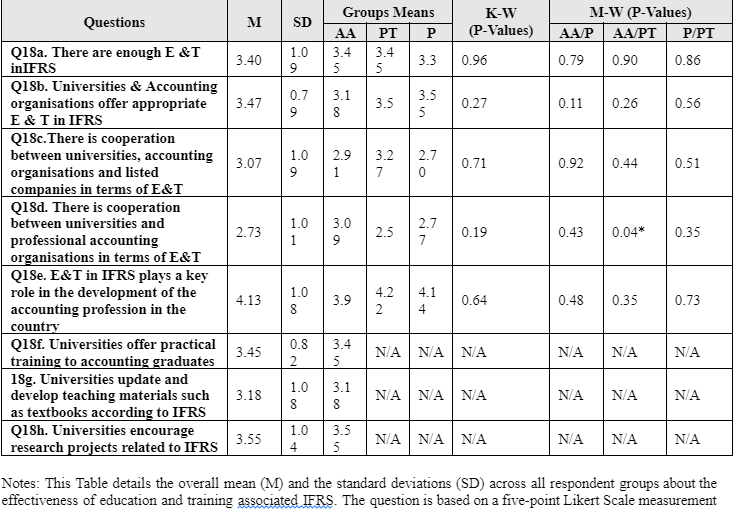

6.3.2.1 Preparers of Financial Statements

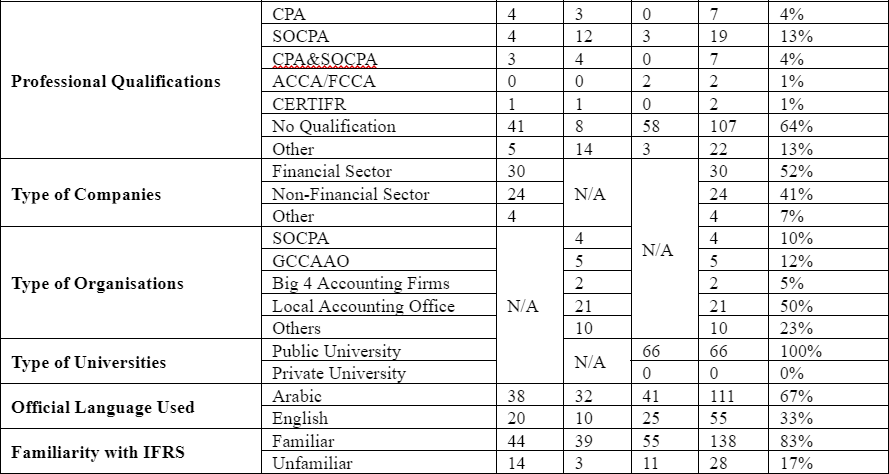

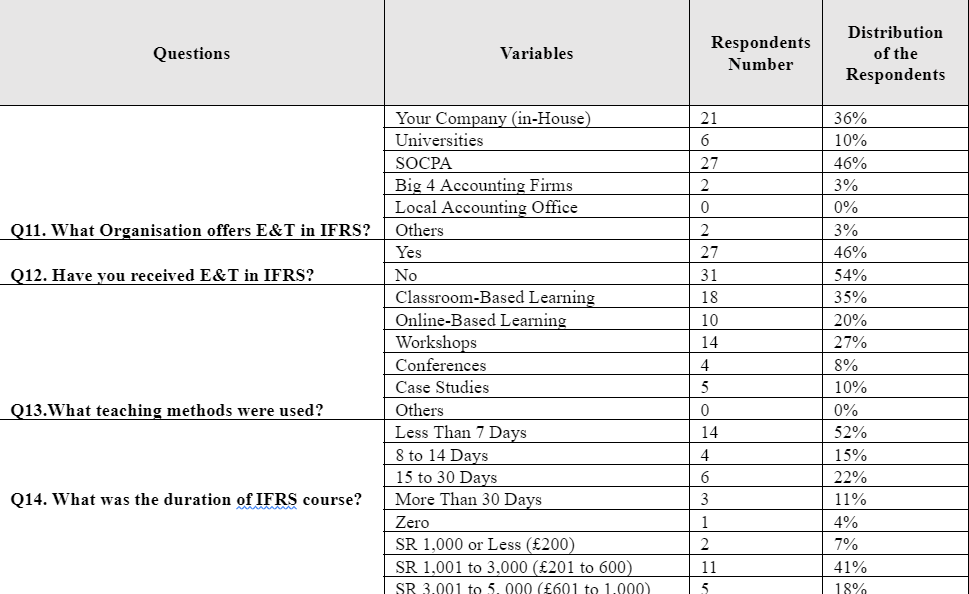

Table 6.3 provides a summary of the preparers’ responses in terms of the nature of IFRS education and training available in Saudi Arabia. The analysis reveals that, SOCPA ranked the first in terms of providing IFRS education and training, which 27 out of 58 (46%) of the preparers agreed that, SOCPA is the dominant provider, which offers the majority of IFRS training in the country. The results of the questionnaire surveys also indicate that, the preparers’ own companies (in-house) ranked the second in terms of offering IFRS education and training, which 21 out of 58 (36%) of the preparers agreed on this matter. On the other hand, local accounting offices have been rated poorly. This finding was expected because the number of local accounting offices are limited, which may have a negative impact on the practice of the accounting profession in Saudi Arabia (Nurunnabi, 2018).

Another reason for a low percentage of IFRS training being reported from Saudi local accounting office’s is that, the main role of these offices is offering accounting services such as audit and taxation, so they have less interest in providing IFRS training (SOCPA, 2019). In addition to this, it is apparent from Table 6.3 that27 out 58 (46%) preparers obtained IFRS training, while 31 out 58 (53%) did not obtain these training. These results demonstrate that, more than half of the preparers did not acquire suitable training associated with IFRS. This may be due to some potential reasons discussed earlier in the extant literature such as (i) a lack of training opportunities; (ii) poor quality education and training; and (iii) the high costs associated with obtaining the necessary knowledge (Sucher and Jindrichovska, 2004; Alkhtani, 2010; Nurunnabi, 2017; Pawsey, 2017). When the participants were asked about the teaching method used in training sessions, 18 (35%) respondents acquired knowledge via classroom based-learning, 14 (27%) learned via workshops, followed by 10 (20%) who received education via online-based learning. However, 5(10%) respondents gained information via case studies and only 4 (8%) others via conferences. Thus, the respondents used various teaching approaches in order to obtain education and training associated with IFRS. Consistent with these answers, earlier literature emphasised on the importance of the use of various teaching approaches. For example, Jackling et al. (2012) argued that, the traditional lecture approach such as a classroom-based learning approach was an active learning method, which offered a great level of engagement and interaction between the instructor and the students in IFRS education. On the other hand, other authors highlighted the importance of the use of non-traditional teaching approach such as online-based learning methods and case studies approach (Holtzblatt and Tschakert, 2011; De Souza Costa et al., 2018).

For instance, Holtzblatt and Tschakert (2011) suggested that, learning IFRS via online was flexible and accessible teaching approach, which helped the interested parties such as the students to gain a wide range of information in IFRS. Additionally, De Souza Costa et al. (2018) emphasised on the value of the use of case studies for obtaining knowledge associated with IFRS, by arguing that such learning approach played a key role in enhancing the students’ skills in order to understand IFRS.

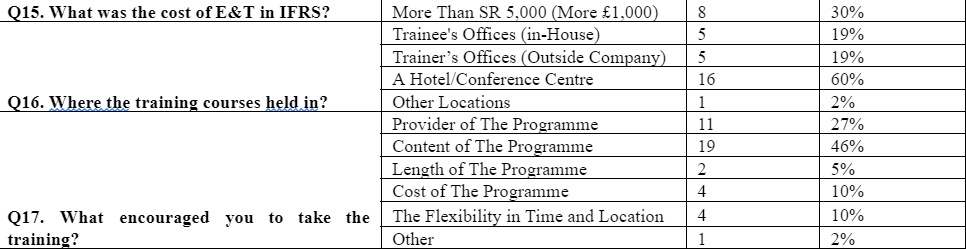

Table 6. 3: The Nature of Education and Training associated with IFRS amongst Preparers

Notes: The Table shows the frequency answers of the questions associated with the nature of education and training amongst the 58 preparers (P). Abbreviations: E&T= Education and Training.

From the results present in Table 6.3, it is apparent that more than 50% of the respondents attended courses of less than 7 days duration, while only 11% attended a course lasting more than 30 days. With respect to the costs of IFRS education and training, about 41% of respondents estimated that the costs of education and training ranged from SR 1,001 to 3,000 (£201 to £600). This is closely followed by 30% of those who estimated that the costs were more than SR 5,000 (more than £1,000). This range of prices indicates that, the costs might in some instances to be prohibitive. Meanwhile, fewer respondents reported that the IFRS training was not expensive and that in some instances, it was free of charge. In response to the question “Where are the training courses held?”, almost 60% of the preparers choose hotels and conference centres as the venues for training, whilst 40% split evenly between the trainees and trainer officers. These findings tie in well with the findings of the interviews (Chapter 7), which confirmed the importance of having the training courses outside the trainees’ own company offices. This might be because having the training off-site may provide a more comfortable learning environment, where the participants could share their ideas and experiences and facilitate active interaction between trainers and trainees. The respondents were also asked to identify which factors motivated individuals to take particular training sessions. As shown in Table 6.3 that, 46% of the respondents answered that the content of the programme was paramount, while 27% cited that the providers (trainers) represent a key motivation for the choice of training. In contrast, the length of the programme ranked as the least motivating factor at only 5%.

6.3.2.2 Accounting Academic and Professional Trainers

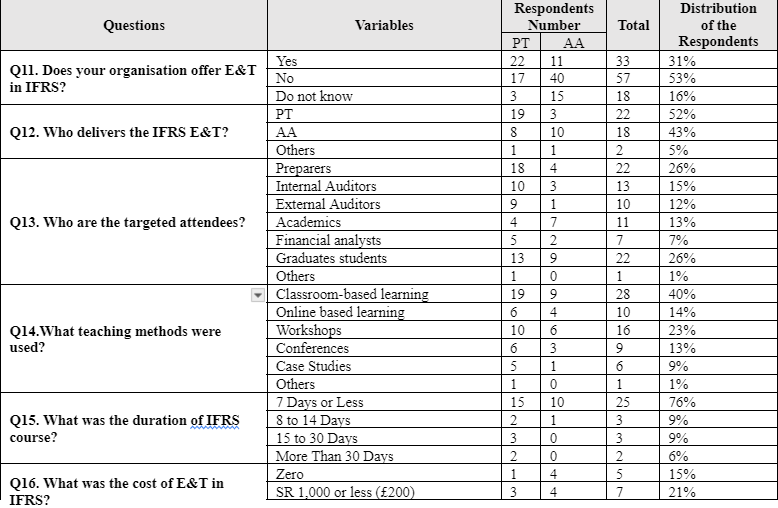

Table 6.4 presents the results obtained from the accounting academics (AA) and the professional trainers (PT) with regard to the nature of education and training associated with IFRS. From the data supplied in Table 6.4, it reveals that 57 out of 108 (53%) AA and PT respondents pointed out that organisations such as universities and SOCPA did not offer adequate education and training associated with IFRS. In contrast to this result, only 33 out of 108 (31%) of the respondents stated the opposite. Respondents were asked to indicate “who delivers the IFRS education and training?” As indicates in Table 6.4 that 52% answered that, the professional trainers (PT) delivered IFRS training. This is followed by 43%, who reported that, it was the accounting academics (AA). Thus, IFRS requires more of a practical explanation than a theoretical one, so the majority of the participants could have assumed that, the professional trainers are better placed and have the necessary expertise to deliver practical knowledge and discuss recent and relevant real-life examples of IFRS (Han et al., 2019).

Table 6. 4: The Nature of Education and Training associated with IFRS amongst Accounting Academics (AA) and Professional Trainers (PT)

In terms of the targeted attendees, Table 6.4 highlights that both respondents of AA and PT commented those preparers and the graduates’ students rated as the highest targeted audiences for the IFRS training. In the meantime, financial analysts and othersrepresented the lowest audiences. In response to the question: “What teaching methods were used?” 40% of the respondents relied on classroom-based learning as the most frequent teaching method used. This is followed by workshops (23%) which were ranked as the second teaching approach. Nonetheless, less than 15% identified other tools, such as online-based learning, conferences, and case studies considered in some instances key teaching methods. It is interesting to note that, a high percentage of accounting academics and professional trainers agreed with the preparers that, classroom-based learning is the most used teaching approach, as opposed to the remaining teaching approaches. With respect to the duration of an IFRS course, more than 75% provided a course run for less than 7 days duration. This response is also in line with the result of the preparers, who avail the benefit of the IFRS course that runs up to 7 days. When the participants were asked about the range of education and training course fees, 85% of the providers charged a price from SR 1,000 to more than 5,000 (£250 to more than £1000). While 15% of the participants estimated that the costs were low or free. However, since the IFRS training is relatively costly, it could discourage the interested parties to access into an adequate IFRS training. In response to question 17, almost 50% reported that the trainer’s offices were typically used for training with less than 10% utilising venues in the trainee offices or other locations.

- 5. Other includes all of the above variables in question number 13 of Table 6.4.

6.3.3 The Effectiveness of education and training associated with IFRS in Saudi Arabia

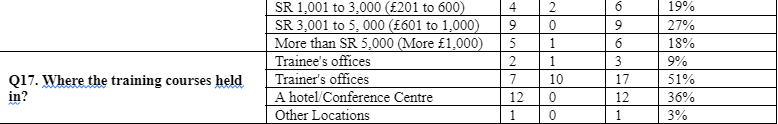

This section of the questionnaire requires all of the respondents to assess the effectiveness of education and training associated with IFRS. Table 6.5 illustrates the statements that have emerged from the prior literature designed to measure the effectiveness of IFRS education and training. The inspection of the Table indicates that the question asked about the whether IFRS education and training play a key role in the development of accounting profession, recorded the highest overall mean of 4.13, amongst all the respondents. This answer can be explained by the fact that the majority of the participants agreed that adequate IFRS education and training is important for developing the accounting profession in Saudi Arabia. As mentioned in the literature review, there was a relationship between accounting education and the accounting profession, whereby a sufficient education and training led to enhance accounting practices including the use of IFRS (Loyeung et al., 2016). Additionally, a recent study in the MENA region including Saudi Arabia found that there is a gap between accounting education and accounting practice and the IESs are not in use in the universities (Mah’d and Mardini, 2020).From a theoretical institutional perspective, normative pressure that generated from accounting education could affect the accounting profession and the use of IFRS in developing countries (Nurunnabi, 2017). Similarly, Hassan et al. (2014) found that, there was a normative pressure impacted from the accounting education on the use of IFRS in Iraq.

Table 6. 5: The Effectiveness of Education and training associated with IFRS

Table 6.5 above also provides a list of statements related to the effectiveness of education and training associated with IFRS in Saudi Arabia. It reveals from this table that, the statements are related to whether universities: (i) encourage research projects related to IFRS; (ii) provide appropriate training; (iii) make practical training available to accounting graduates; (iv) ensure the existence of relevant education and training; and (vi) develop essential teaching materials, such as textbooks, recorded means scores of 3.55, 3.47, 3.45, 3.40, and 3.18 respectively. With regard to cooperation between the three institutions namely; universities, SOCPA, and listed companies in terms of education and training related to IFRS, the results reported an overall mean below the mid-point, 3, while the communication between SOCPA and universities had an overall mean of 2.73 which was the lowest overall mean among the all of the other statements. There was a level of disagreement amongst the respondents with regard to the existence of cooperation among these three institutions in terms of IFRS education and training. These results are in line with the interview findings (Chapter7), where the interviewees were in the opinion that the lack of cooperation and communication mechanism among the universities, SOCPA, and listed companies exist (see more in section 7.7). In line with these findings, evidence from the literature also highlighted a poor relationship between the universities and professional accounting bodies in terms of providing appropriate training in IFRS (Gallhofer et al., 2009). However, several studies from the literature emphasised on the importance of the engagement between universities and the professional accounting bodies in terms of IFRS education (Larson and Brady, 2009; Stevenson, 2010; Stoner and Sangster, 2012; AlMotairy and Stainbank, 2014; Hassan et al., 2014; Nurunnabi, 2015).

It can be seen from the data supplied in Table 6.5 that the groups’ means are different with regard to the effectiveness of education and training associated with IFRS. However, the groups’ means that recorded the highest regarding the statement associated with roles of IFRS education in developing the accounting profession in Saudi Arabia with means of 3.90 for accounting academics, 4.22 for professional trainers, and 4.14 for preparers respectively. By contrast, the group means reported the lowest in terms of the cooperation between the three stakeholders namely; universities, SOCPA, and listed companies with a mean of 2.91, for accounting academics, 3.27 for the professional trainers, and 2.70 for preparers. In response to question (18d) which asked about the cooperation between both universities and professional accounting organisations in terms of IFRS education and training, the group means were recorded with 3.09, for accounting academics, 2.5 for the professional trainers, and 2.77 for preparers, which further indicates that, there was a lack of interrelationship between universities and SOCPA in terms of providing the adequate IFRS education and training.

As discussed earlier in this section, the non-parametric tests, Kruskal-Wallis (K-W) and Mann-Whitney (M-W) were carried out to measure the five-point-Likert scale questions. Both tests will aid the researcher to discover if there are significant differences between the groups’ mean. An analysis of the results of both tests (K-W and M-W) as shown in Table 6.5, reveals that, there are no significant differences across all the statements with the exception of the statement related to the cooperation between universities and professional accounting organisations in terms of provision IFRS education and training in question (18d). However, The result of ( M-W) test for this statement reveals that there is significant difference between the group means of AA and PT, as a high number of PT respondents, as opposed to the AA group, disagreed on the existence of the institutional collaboration between universities and SOCPA. This significant difference can be explained by the fact that, PT respondents blamed the limited roles of universities with regard to the development of IFRS education in the country (see section 7.7.2).

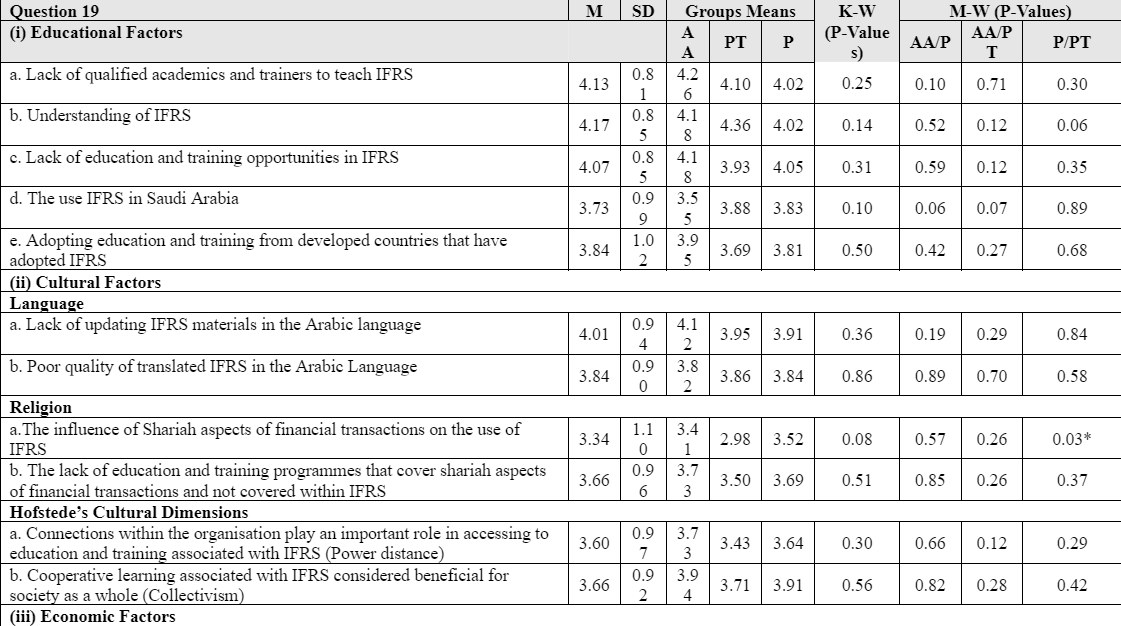

6.3.4 The Institutional Factors Affecting Education and Training of IFRS

This section intends to find out the impact of various institutional factors namely; educational, language, religious, cultural, economic, political and other factors on education and training associated with the implementation of IFRS in Saudi Arabia. These factors will be discussed in greater details in the flowing subsections.

6.3.4.1 Educational Factors

Table 6.6 indicates that, the overall means across the statements associated with the educational factors ranged from 4.17 to 3.73. These results may reveal that the majority of respondents highlighted, in aggregate, their agreement about the influence of educational factors on education and training associated with IFRS. For example, the statement related to the importance of understanding IFRS recorded the highest mean of 4.17. This was followed by an overall mean of 4.13 for the statement associated with a lack of qualified academics and trainers to teach IFRS in Saudi Arabia. A possible interpretation for this result might be that, these educational related factors including the dearth of qualified academics and trainers may have an influence on the level of understanding IFRS. Thus, interested parties such as students and trainees may find it difficult to gain access to proper IFRS education programmes (see more in section 7.8.1). This finding was also supported by the extant literature, which found that, the limited number of qualified academics to teach IFRS had a negative impact for the students to exercise the professional judgments according to IFRS (Wells, 2011; Jackling et al., 2012; Stoner and Sangster, 2012; Patro and Gupta, 2012, Albader, 2015; Folashade et al., 2016). In this regards, the successful inclusion of IFRS into accounting educational programmes depends on the availability of these qualified accounting academics (Patro and Gupta, 2012).

With respect to the statement on education and training opportunities in IFRS, the majority of respondents felt that, lack of such opportunities also had an influence on the use of IFRS. This result was in line with the earlier literature, where the deficiencies in education and training opportunities had prevented accountants from understanding IFRS properly (Nurunnabi, 2012; Hassan et al., 2014).

In terms of the impact of the educational factor on the use of IFRS in Saudi Arabia, the respondent’s answers suggested that, IFRS education had an impact on the use of IFRS. The participants also emphasised, in aggregate, their agreement with the view that adopting educational and training programmes from other countries such as the developed countries in Saudi Arabia could have an influence on IFRS education and training in the country. This finding is also supported by Abubaker (2014), who found that, most of the GCC countries, including Saudi Arabia, were influenced by the developed countries accounting education system due to the countries’ economic and political relations. From institutional theoretical framework, mimetic pressure from developed countries accounting education had an impact on IFRS education and training in Saudi Arabia, as seventy-five of the interviewees confirmed that adopting and accepting IFRS education from the developed countries is beneficial (see more in section 7.8.1.8). These IFRS textbooks used and programmes taught in Saudi Arabia were largely copied from those utilised in developed countries by Saudi accounting academics and professional trainers, who had their education from the developed countries in order to improve education and training practices in the country. In supporting this argument, Powell and DiMaggio (1983) argued that, mimetic pressure may lead organisations to copy other organisations’ systems for the purpose of improvement and development.

6.3.4.2 Language Factors

This sub-section investigates the respondents’ perspectives with regard to the language factors. Table 6.6 represents the statements associated with the language factors and the statement related to the lack of updating IFRS materials in the Arabic language recorded an overall mean of 4.01, which seems to be that, majority of the respondents from most of the groups showed their agreement on the significant impact of this factor on IFRS education and training. In addition, the poor quality of translated IFRS in the Arabic language reported an overall means above mid-point of 3, which may illustrate that, a large number of participants are expressing their level of agreement with the significant impact of these factors on IFRS education and training. This answer from the questionnaire respondents were in line with findings from the interviews where Eighty-five percent of the interviewees expressed their opinions with regard to the impact of the quality of the Arabic IFRS translations on IFRS education (see more in section 7.8.2).

6.3.4.3 Religious Factor

This sub-section demonstrates the answers of the respondents with regard to the impact of religious factors on IFRS. The data supplied from Table 6.6 indicates that the question asked about the influence of the Shariah aspects on the use of IFRS, had an overall means of 3.34 which shows that, there are some elements of agreement towards the influence of religion factor on the use of IFRS in Saudi Arabia. In addition, the results of the P-value for the M-W test highlight significant differences between the groups' means of preparers and professional trainers with regard to the same statement. For example, a large number of preparers articulated a greater degree of belief in the influence of the religious factor on the use of IFRS compared with professional trainers due to the differences between IFRS and the requirements of the Shariah aspects of the financial transactions. Additionally, Table 6.6 presents responses concerned about the influence of the lack of IFRS education that covers the Shariah aspects of financial transactions. It reveals that this statement reported an overall mean above the mid-point of, 3, which suggest the importance of covering and teaching the topic related to Islamic financial transactions (more information in section 7.8.3).

6.3.4.4 Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions

This sub-section provides the statements associated with the factors of Hofstede's cultural dimensions. The answers from Table 6.6 reveals that, the impact of the connection on accessing to IFRS training, recorded a mean above the mid-point of , 3, which may further emphasis that, the majority of the respondents believed in the connection with regard to accessing IFRS training that had an impact on the development of accounting education in the country. In response to the question associated with the impact of the cooperative learning on IFRS education, an overall means above the mid-point of, 3, which indicated that most of the respondents were in the agreement that this kind of learning was beneficial for society.

6.3.4.4 Economic Factors

The respondents were in agreement that, economic environment has an impact on IFRS education and training with overall means of 4.05. In relation to the impact of the Saudi economic environment on accounting education, the results suggested that, all the economic factors had an impact on education and training associated with IFRS. This finding is supported from the interviews (chapter 7), as seventy-five percent of the interviewees emphasised on the relationship between economic development and IFRS adoption and their education, where a strong economy may aid to ensure the availability of the outstanding quality of IFRS education and training (more information in section 7.8.5). Earlier literature proved the importance of economic factors in supporting and enhancing accounting education; which in turn, may contribute to satisfying accounting practices (HassabElnaby et al. 2003; Tahat et al., 2018;Nurunnabi, 2018; Yamani and Almasarwah, 2019). In institutional theoretical framework context, there is a coercive pressure originating from the economic factors on education and training, associated with IFRS as the education system in general and the accounting education, in particular, are entirely dependent on the national financial and funds support from the Saudi government in order to improve the level of education in the country (Yamani and Almasarwah, 2019). Part of the economic factors is the costs associated with IFRS training and when respondents were asked about the impact of these costs on IFRS training, an overall mean of 3.98 was recorded which suggest that, the costs factor can be a barrier to access into the required IFRS education and training.

6.3.4.5 Political Factors

An inspection of Table 6.6 below reveals that, the impact of the political factor on IFRS education and training has a mean of, 3.86, which indicates a level of agreement among the respondents in relation to the influence of the political environment in supporting accounting education in Saudi Arabia. Linking this answer to the institutional isomorphism, it can be noted that, there was a robust coercive pressure generated from the political factor on the accounting education, as the Saudi government is responsible for supporting and funding the development of the education system in the country. However, this argument is not in line with other studies that applied institutional isomorphism, which further found that, there were a lack of coercive pressure stemmed from political factor (governments) on accounting education as both governments of Iraq and Libya had limited funding on the development of accounting education ( Hassan et al., 2014; Abubaker, 2014).

6.3.4.6 Other Factors

The participants were asked about other factors that may have an impact on accessing IFRS education and training. It turns out that, the complexity of IFRS is one of these factors, with a mean of 3.94. This score may be explained by IFRS complexity impacted on accessing to IFRS education and training. The higher complexity of IFRS may create great difficulty in finding the required educational and human resources, such as IFRS textbooks and qualified accounting academics and trainers (more information in section 7.8.7). Evidence from the literature emphasised that the IFRS complexities and difficulties were one of the impediments to IFRS adoption and IFRS education ( Larson and Street, 2004; Folashade et al., 2016; Ediraras et al., 2017; Jermakowicz et al., 2018; Siregar et al., 2020) For instance, Ediraras et al. (2017) and Siregar et al.(2020) argued that, there was a significant demand for IFRS education and training but the complexity of the standard was a potential factor that hinders its understanding and implementation.

Another factor considered was the irrelevance of IFRS to Saudi Arabia; but the results revealed that a majority of the respondents disagreed with this statement, on the assumption that IFRS was relevant to the country because Saudi is moving towards international economy status and IFRS adoption is part of this movement. In terms of the result of the K-W tests with regard to the above statement, Table 6.6 reported that there are significant differences between the three groups’ means. Additionally, the P-value for the M-W test illustrated a significant difference between preparers on the one hand and both accounting academics and professional trainers on the other, on the statement associated to the irrelevance of IFRS to Saudi Arabia. A possible explanation of this result is that a high percentage of accounting academics and professional trainers felt that IFRS are relevant for the Saudi context, on grounds that, the Saudi economy is in its development phase, of which the adoption of IFRS plays an important and active part. However, preparers believed that, IFRS is designed for developed countries and perhaps they perceived that, IFRS does not fit with the Saudi business environment.

In response to the question about the influence of the principles-based nature of IFRS on education and training, the overall means was below the mid-point, 3, which indicated that this factor may have a slight influence on accounting education. With regard to the M-W test related to the above statement, there was a significant difference between preparers and accounting academics, as shown in Table 6.6, the group mean of preparers was greater than the group mean of accounting academics. This may indicate that, a great number of preparers compared with accounting academics, suggested that the principles-based approach had an influence on the development of IFRS education, as the use of principles-based approaches over rules-based there is more flexible in terms of providing greater understanding in exercising accounting professional judgments (Wells, 2011).

6.4 Summary and Conclusion

This chapter discussed the results of the questionnaire survey, obtained the perceptions of the accounting academics, professional trainers, and the preparers of financial statements on education and training associated with IFRS in Saudi Arabia. In terms of the nature of IFRS education and training, the findings indicated that, most of the preparers agreed that, SOCPA is the key provider of IFRS training in the country. In contrast, the local accounting office rated poorly. From the accounting academics’ and professional trainers’ perspectives, the role of SOCPA and universities in providing IFRS education and training was seems to be limited. As a result, a large number of preparers did not obtain training. With respect to the teaching approach, the three respondent groups used different learning approaches in order to learn about IFRS with a suggestion that, the length of the course should be short because preparers do not have the time to attend for long training sessions. In terms of the location where the training sessions should be held, it is interesting to note that the academics and trainers’ views were different from those of the preparers. The results reveal that, the preparers viewed hotels and conference centres as appropriate learning environments, whilst both the academies and trainers used their trainer’s offices for training (Section 6.3.2).

As discussed earlier in this chapter that a larger number of respondents agreed that the professional trainers and accounting academics were the two main providers of education and training in Saudi Arabia. In the meantime, both preparers and accounting graduates were rated as the main attendees at IFRS sessions. In relation to the factors that motivated individuals to take particular training sessions, it turns out that, both the content of the programme and the speakers are important elements for taking training, whilst other factors such as the length of the programme did not have a significant impact on attending these training sessions (Sub-section 6.3.2).

Regarding the effectiveness of education and training in IFRS, the highest overall mean was associated with the statement that argued the IFRS education and training played a key role in the development of accounting practices in Saudi Arabia. This statement also recorded the highest group means across all respondents’ groups, whilst the overall mean noted the lowest with regard to the statement of the cooperation between the providers (universities and SOCPA) and the receivers (listed companies) of education and training associated with IFRS (Section 6.3.3)

In terms of the various institutional factors that may have an impact on education and training associated with IFRS in Saudi Arabia, educational, language, religious, Hofstede’s cultural dimensions, economic, and political factors have been identified as key factors. With respect to the educational factors, the responses indicate that, all of the statements related to the educational factors had an influence on education and training associated with IFRS. With the exception of the statement associated with adopting education and training from developed countries, which had an impact on this matter. In terms of the language factors, the results emphasised that the problem associated with the shortages of updating IFRS materials and quality of translation into the Arabic language are the issues that impacted on the development of IFRS education and training. Additionally, respondents demonstrated their agreement on some elements of the impact of the Shariah aspects of financial transactions on the IFRS in Saudi Arabia.

The respondents also revealed that there was a relationship between economic development of accounting education and this had an impact on the use of IFRS in Saudi Arabia. However, the costs associated with IFRS education and training had an influence on accessing education and training related to IFRS. The results associated with the political factor revealed the impact of the political environment in supporting accounting education and training. In terms of the other factors, the findings reported that both factors including complexity of IFRS and the principles-based nature of IFRS had an influence on IFRS education and training. Additionally, the statement associated with the irrelevance of IFRS to Saudi Arabia is also one of the other factors and the results further revealed that, a majority of the respondents disagreed with this statement, assuming that IFRS is relevant to the country because Saudi is moving toward international economy status and IFRS adoption is part of this movement (section 6.3.4).

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts