Conventional Oil Recovery Limitations

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

As societies grow and people seek a higher standard of living, the demand for energy also increases. It fuels economies, schools, homes, industry, transportation, and construction. It is a vital element of our daily lives. The energy system today is the result of many decades of choices, made by energy suppliers, consumers, and governments. Societies want reliable energy, which are affordable and widely available. As a result, hydrocarbons represent over 80 per cent of the energy mix (Shell Energy Transition, 2019). In fact, during the exploitation of the hydrocarbons in a new reservoir using conventional methods, the amount of oil obtained from it, varies from 20 to 40% of its potential. At the same time, it is estimated that, there is still about 60 to 80% of the oil remaining in the reservoir, if only the conventional oil recovery methods are utilised (Kamal et al., 2015, Abidin et al., 2012). For this reason, enhanced oil recovery (EOR) methods are seen, therefore inevitable for application in most of the oil fields to recover this vast fraction of unrecovered oil. It is an essential technique in oil industry worldwide, as there is a decline in production from natural fields and new oil field discoveries are not sufficient to match the growing energy demand, as well as difficulties in finding a new oil field (Abidin et al., 2012).

The petroleum recovery process occurs in three different stages: primary, secondary and tertiary recovery stage. The primary recovery stage takes place when the reservoir uses its natural energy to force the oil to the wellbore, and it is often referred to as the initial production stage. According to Farouq-Ali and Thomas (1996), this stage can recover over 50% of the original oil in place, and it is dependent on the type of hydrocarbon and the reservoir drive mechanism. For example, in case of oil sand, the primary recovery is zero; in contrast, the recovery from light oil reservoir and a water drive can reach until 50% or even more in reservoir, which is effectively gravity driven. The secondary recovery stage, on the other hand, utilises the injections in order to repressurise the reservoir and displace the oil to the producing well. It is done through the injection of gas or water, and water flooding is thus referred to as secondary recovery (Ahmed and McKibbey 2005). The third stage or tertiary recovery is also referred to as enhanced oil recovery (EOR), and targets what is left in the reservoir. This stage also involves the injection of gas or fluids inside the reservoir, but with the aim of reducing the forces such as interfacial and viscous forces holding the oil, to facilitate the production.

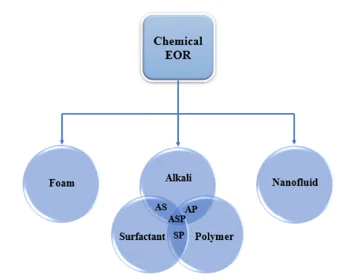

EOR method helps to maximise the oil reserves recovered, prolong the life of fields, and also increase the recovery factor. It is an essential tool for firms, helping to maintain production and increasing the returns on older investments. In the EOR process, there are three primary techniques applied, which are gas injection, chemical injection and thermal injection. Chemical enhanced oil recovery (cEOR) is one of the promising EOR methods, in which polymers, surfactants and alkaline are utilised. Polymers, on the other hand, enhance the viscosity of the displaying fluid and consequently decrease the water/oil mobility ratio (Kamal et al., 2015; Abidin et al., 2012; Buchgraber et al., 2009).

Polymers are substances consisting of long and repeating chains of molecules. These substances have unique properties, depending on the kind of molecules being bonded and how they are bonded (Bradford, 2017). A chemical EOR method, uses polymers, is called polymer flooding, and this has been utilised in the field for about 40 years (Mogollon and Lokhandwala, 2013). Polymer flooding consists of combining a long-chain polymer molecule with water injected, in order to increase the water viscosity, so that the fluid is more difficult to flow than the oil, and consequently, the oil production increases. This technique improves the areal and vertical sweep efficiency and as a consequence improves the water/oil mobility ratio (Gbadamosi et al., 2019, Abidin et al., 2012)

To further improve the enhanced oil recovery process and get a better performance, recently new methods are also being applied. Different chemicals are combined, and it is called “binary combination of chemical EOR”. The combination includes, Alkali-surfactant, Alkali-polymer, surfactant-polymer and Alkali-surfactant-polymer flooding. Surfactants can be used in combination with polymers; as they decrease the interfacial tension between the water and oil and wipe out the oil trapped from the reservoir rock and consequently boost the oil production (Pope, 2007). This leads to a reduction in residual oil saturation and it further improves the macroscopic efficiency of the process.

Research problem

Polymers have been used for many years in oil and gas industry with the purpose of increasing the viscosity of the injected brine in order to boost the oil recovery. Conventional polymers, which are frequently used, present some problems for today’s world that tries to go green. The most commonly used are Hydrolysed polyacrylamide (HPAM) and biopolymer xanthan gum. However, HPAM is susceptible to high salinity and temperature; in addition, it is harmful for the environment due to its synthetic nature. Xanthan gum on the other hand is highly susceptible to oxidation and biodegradation. The oil and gas industry aim for a polymer, which is tolerant to high salinity and also high temperature conditions in the reservoir.

Take a deeper dive into Harnessing Solar Energy with our additional resources.

This leads to the following research questions:

What are the advantages and disadvantages of using conventional polymers?

Which type of polymer is better and why?

What are the environmental problems associated with conventional and natural polymer?

Is it economically feasible to adapt natural polymers?

Aims and Objectives

To investigate the existing natural and conventional polymers

To understand the effect of high and low salinity on polymer flooding performance

To understand the principles behind polymer flooding

To determine the behaviour of natural and conventional polymers in porous media

Structure of the dissertation

This research dissertation seeks to understand and give a huge overview on polymer flooding processes by critically reviewing the advantages and disadvantages of using both conventional (synthetic) and natural polymers; and seeing if there is a possibility for oil and gas industry to shift to natural polymers. This dissertation starts by introducing the polymer flooding topic in chapter 1 (this chapter) by defining polymer flooding, the problem statement and further highlighting the aims and objectives of the dissertation. The following chapter looks at the literature review for evaluating the existing journals and books, which talk about polymer flooding. It also divides the different types of polymers and highlights their rheological properties, adsorption, thermal stability, recovery factor and etc. The next chapter describes the methodology, used in this research project. Chapter four analyses the results and discusses the temperature, salinity and recovery factor of both types of polymers, and at last the chapter five concludes the whole research.

CHAPTER 2

LITERATURE REVIEW

Overview

This chapter discusses the literatures related to the topic of interest, pointing on different types of polymers available on the marked.

Mechanism and principle of polymer flooding

Polymer flooding projects typically involve the mixing and injection of polymer over a prolonged time until almost 1/3 or 1/2 of the pore volume in the reservoir has been injected. Then, this polymer “slug” is accompanied by continued long-term flooding of water to push the polymer slug and the oil bank in front of it towards the production wells. Over a period of years, this polymer is continuously pumped in order to achieve the targeted pore volume. As the water is pumped in the reservoir, it follows the path of least resistance (usually the highest permeability layers) to the area with a lower pressure of the offset production wells. Moreover, if the viscosity of the oil in place is higher than that of the water injected, the water will finger through this oil, resulting in low sweep efficiency or bypassed oil (Abidin, Puspasari and Nugroho, 2012).Polymer flooding technology increases the recovery of oil through a combination of mechanisms such as mobility control, disproportionate permeability reduction and viscoelastic nature of the polymers.

Mobility control

The mobility ratio can be defined as the ratio between the mobility of the injectant (water) and the mobility of the displaced fluid (oil). The mobility ratio of a waterflood is represented in the equation below:

Mr=KwoKow

Where

Mr – Mobility ratio

o – Oil viscosity (cP)

w – Water viscosity (cP)

Ko – Permeability to oil (mD)

Kw – Permeability to water (mD)

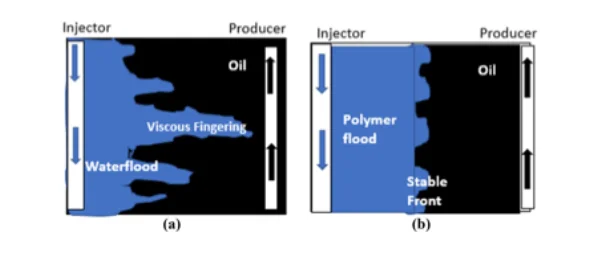

The mobility ratio determines the stability of the oil displacement process. The main goal of any EOR process is to get Mr less than 1. If Mr > 1, this means that water is more mobile than the hydrocarbon and indicates an unfavourable situation as water fingers through the oil zone (viscous fingering), leading to an early breakthrough and lower efficiency of oil displacement (see figure 2 below). Favourable Mr is achieved in polymer flooding by increasing the viscosity of the water. It is always required that Mr 1 to ensure a high macroscopic sweep efficiency. Figure 2 below shows how polymer flooding influences the recovery of oil by reducing the mobility ratio. The presence of polymer in the displacing phase induces an increase in the injectant viscosity. Consequently, this leads in a stable front of the displacing phase entirely denuded of viscous fingering a channels within the reservoir, therefore, resulting in a higher recovery of oil. (Sorbie, 1991; Zaitoun et al., 2012; Delshad et al., 2008).

Disproportionate permeability reduction (DPR)

In addition to the principle of mobility ratio stated above, polymer flooding boosts the sweeping efficiency through disproportionate permeability reduction. As some reservoirs have heterogeneous nature, they have an uneven distribution of permeability (having varying permeability in different layers). This results in the channelling of excessive production of water into layers with high permeability, resulting in a large amount of mobile oil and gas remaining trapped in low permeability areas, thereby, resulting in poor recovery during primary and secondary production stages (Mishra et al., 2014). The polymer solution injected in the heterogeneous reservoir, during polymer flooding, builds up flow resistance to water in the areas of the reservoir it penetrates; thus, reducing the relative permeability of water (Krw) while making sure there is little or even no reduction in the relative permeability of oil (Kro). This mechanism is called disproportionate permeability reduction. The increased resistance of the polymer to water subsequently diverts the injected water into poorly swept or unswept (low permeable) zones of the reservoir through segregation of flow paths and the formation layers on pore wall by the adsorbed polymer; hence, resulting in a higher recovery of oil (Wei, Romero-Zerón and Rodrigue, 2014).

Viscoelasticity of polymer molecules

The viscoelasticity of polymer is the third mechanism proposed to be responsible for increased macroscopic efficiency during polymer flooding. Polymers undergo a sequence of expansion and contraction during their flow in porous media, unlike Newtonian fluids (Veerabhadrappa, Trivedi, and Kuru, 2013). This allows the polymeric molecules to produce additional “elastic viscosity” that enhances microscopic and macroscopic displacement efficiency. Urbissinova, Trivedi and Kuru (2010) and Veerabhadrappa (2013) studied the effect of viscoelastic properties of polymer on macroscopic efficiency. A polymer of similar average molecular weight but different molecular weight distribution was used to generate the elastic difference of the polymer solution with the same shear viscosity. The outcome of their experiment showed that, polymer solutions with high elasticity, further exhibited significantly higher resistance to flow through porous media and the stability of the propagating front, hence minimising fingers. This cumulated in a lower residual oil saturation, higher sweep efficiency, and improved oil recovery.

Rheology in porous media

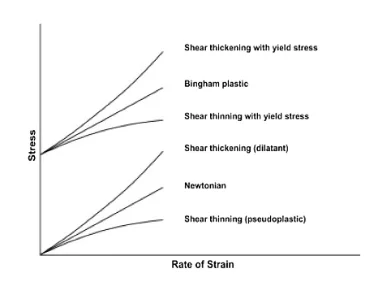

In order to design and evaluate polymer flooding, it is fundamental to have a broad knowledge of polymer solution rheology at reservoir conditions (Kaminsky et al., 2007). Rheology can be defined as the study of flow and deformation of a system under a variety of shear. As such, when talking about the flow in porous media, the study of rheology is essential because it helps to understand the behaviour of the fluid. In porous media, the fluid can present Newtonian and non-Newtonian behaviour. For a Newtonian fluid, the viscosity is represented by the relationship between the stress and shear rate. The viscosity remains constant in a Newtonian fluid, no matter the amount of shear applied; thus, the relationship between the viscosity and shear stress is linear, which means that viscosity versus shear stress graph will be a straight line. The fluid on this case experiences a direct proportionality between the stress and strain, and the flow is laminar (Sochi, 2010). The non-Newtonian fluid viscosity, on the other hand, does not have a constant viscosity at all shear rate; thus, apparent or effective viscosity is used to characterise the viscosity of the fluid at shear rate. Therefore, where the proportionality between the stress and strain is not linear, there the fluid is non-Newtonian. Non-Newtonian fluids can be divided into four groups: dilatant, pseudoplastic, rheopectic and thixotropic.

Dilatant: when shear is applied, the viscosity of the fluid increases. E.g., cornflour, quicksand, and water. Pseudoplastic: the more shear is applied, the less viscous the fluid becomes; e.g., ketchup, polymer. Rheopectic: this type of fluid behaviour is quite similar to dilatant; however, in this case, the viscosity increases with time when shear is applied (time-dependent); e.g., gypsum paste, cream. Thixotropic: the viscosity decreases with time when shear is applied (it is time-dependent); e.g., cosmetic, paint, asphalt and glue.

In the case of a material with pseudoplastic properties, the lower the shear rates, the higher the viscosity, and the recovery of viscosity happens immediately upon the release of shear rate (Rezae et al.; 2016). The most famous model to describe pseudoplastic behaviour is the power-law model, which is seen in the equation below:

μ=Kdudy(n-1)Equation 1

Where:

K – Flow consistency index (cp.secn-1)

du/ dy – Shear rate or the velocity gradient perpendicular to the plane of shear (1/s)

n – Flow behaviour index (dimensionless)

μ – Apparent or effective viscosity as a function of shear rate (cp)

In order to understand the role of rheology in the evaluation of polymer flooding it is necessary to be familiar with mobility ratio (Mr), which is the ratio of displacing phase mobility to displaced phase mobility, as discussed above. Polymer flooding is preferred in reservoirs having the viscosity of the oil < 150 cP, according to screening criteria (Taber, Martin and Deright, 1997). This is the highest limit and reservoirs, which present much lower viscosity of the oil, are potential candidates for PF. The reason for that is that to get a good Mr requires more concentration of polymers, which is not economically feasible. In order to achieve a favourable mobility ratio, viscosity values should be optimised, as high viscosity is not always desirable because of certain problems. First, in order to obtain high viscosity, high polymer concentration is required for making PF more expensive. Second, fluids with high viscosity are difficult to inject. Injectivity refers to how easy the injectant fluid enters the reservoir. Third, fluids with very high viscosity may not reach the region with low permeability. In summary, the optimum viscosity range is a function of the properties of the reservoir and the nature of the reservoir. The optimum value of viscosity is the one, which gives Mr < 1. The optimum range of viscosity of polymer solution is different for different reservoirs, and this is due to differences in viscosity of reservoir oil and effective permeability. By using high MW and higher concentrations, high viscosity can be achieved. In cEOR laboratory investigations, it has been used MW as high as 20 million Dalton (mD); and the polymer concentration should be between 1000 ppm and 3000 ppm for economic purposes (Han et al., 2013). For cEOR applications, two types of rheological properties of a polymer are usually evaluated. Measurements for steady shear are typically performed at a shear rate of 7.3 s-1. The shear rate used in the laboratory study should generally correspond to that experienced in the transportation process in the pipelines and porous media, especially in perforation whole or in the near-wall zone. For laboratory studies, all the literature available suggests a shear rate of 7.3 s-1 as it reflects the shear rate experienced in the reservoir (De Melo and Lucas, 2008). Dynamic rheology was not considered relevant for cEOR applications in the past. However, it has now attracted attention due to the fact that polymer elasticity can help to recover residual trapped oil. Two critical parameters that can be obtained from dynamic viscosity are complex viscosity and elastic modulus.

Thermal stability

In designing of a polymer flooding, laboratory thermal stability data of polymer is an essential factor. Polymer needs to be thermally stable for several months at reservoir conditions. At high temperatures, the polymer thermally degrades, resulting in a decrease in viscosity. This decrease in viscosity adversely affects the Mr. instead of viscosity reduction polymer can also precipitate in the presence of reservoir brine with higher salinity. For a particular polymer to be considered a right candidate, it should have less than 50% of viscosity loss over a specific period of 6 months at reservoir conditions. To select a polymer, it is not only considered properties such as good rheology, thermal stability and adsorption; the polymer should also have good compatibility with reservoir brine, good biological stability, good chemical stability, good injectivity, good shear stability, and low cost. In designing polymer flood there are also other parameters to take into consideration such as reservoir temperature (90C), permeability (>50 mD) and salinity (40 g/L). Reservoirs with high permeability are better candidates as reservoirs with low permeability have injectivity and excess retention issues.

Adsorption

Adsorption can be defined as a process, where a solid holds molecule of a liquid, gas or solute as a thin film. According to Rouquerol (2014), adsorption is the adhesion of ions, molecules or atoms from a liquid, gas or any dissolved solids to a surface. In addition to viscosity, the interaction of the polymer with the rock affects its transportation through the reservoir. Polymer adsorption contributes to polymer retardation, and this is due to mass transfer from the polymer-rich aqueous phase to the solid rock phase. Polymer adsorption is proven to be dependent on the salinity of the aqueous phase, and it is usually considered that the adsorption of higher degree happens at higher salinity (Lake et al., 2014). This is possibly because of the alteration of the polymer conformation in the presence of salts, resulting in increased coiling, and decrease in area per molecule resulting in increased adsorption. Increase in salinity consequently increases the solution’s solvent power, resulting in decreased adsorption (Moudgil and Somasundaran, 1984). The polymer flooding efficiency can be reduced by polymer retention in the reservoir rock surface due to surface mechanical trapping and adsorption. Unlike optimum viscosity, minimum polymer adsorption is always necessary. High polymer retention can decrease the amount of polymer in the flooding liquid, and high concentration is needed to achieve a desirable mobility ratio that may not be economically feasible. Even if it displays promising thermal stability and rheological properties, polymers with higher retention may be rejected at the initial stage. The two types of adsorption, dynamic and static adsorption are used to evaluate the polymer retention behaviour. Polymer retention is dependent on the chemistry of the polymer, composition of the reservoir rock temperature salinity, and composition of the polymer (Gbadamosi et al., 2019).

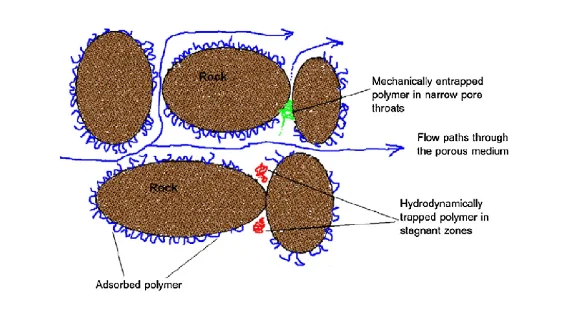

Polymer retention

The main reason for adding polymers to the displacement fluids is to increase the viscosity of the injected brine. However, the major interactions such as London dispersion and electrostatic interactions forces happens between the polymer molecules transported and the surface in the reservoir (Gbadamosi et al., 2018). These causes retention of molecules of polymer and results in the creation of a bank of injection fluid entirely or partially denuded of polymer, depending on the degree of retention of the polymer molecules transported. Therefore, the final viscosity of the injectant in the reservoir is lower than the required target viscosity, thus reducing the effectiveness and efficiency of the polymer flooding (Xin et al., 2018). Factors that influence polymer retention in porous medium include molecular weight, polymer type and concentration, flow rate, rock permeability, temperature, salinity and the presence of clay minerals. Overall, the retention of polymer is an essential factor, whichregulates the economic viability of a polymer flood process, as they affect the permeability of the rock, the viscosity of the injected polymer solution, and consequently recovery process of the oil. There are three main mechanisms of polymer retention in porous media, which are: polymer adsorption, hydrodynamic retention and mechanical entrapment, as seen in figure 4 below.

Mechanical entrapment

There is a similarity between hydrodynamic retention and mechanical entrapment, and both mechanisms occur only in porous media. When large polymer molecules are stuck in a narrow flow channel it said to have occurred mechanical entrapment (Willhite and Dominguez, 1977). According to Herzig et al. (1990), the mechanical entrapment of the polymer flooding can be resumed based on filtration phenomena of deep bed as follow:

The concentration at the end of the core will not achieve the required input concentration or would do so when a large amount of polymer pore volume passes through, which probably may lead to a blockage and this enables polymer to flow through other larger channels.

The other polymer distribution will also not be uniform, enabling large polymers near the inlet, at the core and reducing in that order.

Eventually, there are many trapping zones, the media will be totally blocked, and the consequently the permeability will fall to zero.

Salinity and Concentration Effects on polymer solution viscosity

When the sodium chloride (NaCl) is applied to the solution, the intrinsic viscosity of a homogeneous PAM increases. The viscosity increase is even more apparent when CaCl2 is added to the solution. However, there is a decrease in the viscosity of HPAM when a monovalent salt is added (e.g., NaCl). This happens because the salt added neutralises the charge in HPAM side chains; and when HPAM is dissolved in water, there is a dissipation of Na+ in the water. In high molecular chains –COO− repel each other, making them stretch, increase in hydrodynamic volume, and increase in viscosity. When salt is added to the solution, some Na+ molecules surround –COO− and shields the charge. –COO− repulsion is thus reduced, hydrodynamic volume decreases, and the viscosity also decreases. When divalent salts such as CaCl2, MgCl2, and BaCl2 are added in an HPAM solution, they have a complex effect. The solution viscosity increases at low hydrolysis after it reaches the minimum. At high hydrolysis, on the other hand, the viscosity of the solution decreases until precipitation occurs.

Polymer classification

Generally, there are two types of polymers: synthetic and natural polymer or biopolymer. Synthetic polymers are the ones human-made or synthesised in the laboratory, while natural polymers are obtained naturally and have its origin in animals and plants. In Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) operations, two major types of polymers are used, namely, synthetic polymers with a typical example of hydrolysed polyacrylamides (HPAM) and biopolymers with a typical example of xanthan. Their variations and derivatives are developed to fit particular needs. Between these two types of polymers, HPAM is mostly used due to its advantages in price and large-scale production, and according to Wang et al., (2006) HPAM solutions show significantly greater viscoelasticity than xanthan solutions. Besides HPAM and xanthan, there are still a vast number of polymers, which can be used in EOR and will be discussed later in this paper.

Synthetic polymers

Synthetic polymers are the types of polymers made by humankind or synthesised in the laboratory. The following section will describe these polymers and their specific individualities and properties.

Polyacrylamide

Polyacrylamide (PAM) in its unhydrolysed form, is non-ionic in nature. For EOR applications, a non-ionic PAM is not used because of its high adsorption on mineral surfaces (Sheng, 2010). Therefore, the polymer is particularly hydrolysed in order to reduce adsorption through the reaction of PAM with a base, such as sodium carbonate or potassium hydroxide or sodium. At elevated temperature or pH, the pendant amide group present in PAM may undergo hydrolysis, although PAM does not hydrolyse at room temperature (Kurenkov et al., 2001). This hydrolysis that PAM undergoes was studied and observed by Muller in 1980. Variation in the pH and viscosity of an aged sample was observed at high temperature (Muller, 1981; Muhammad et al., 2015). The hydrolysis reaction converts some of the amide groups (CONH2) to carboxyl groups (COO-). PAM hydrolysis introduces negative charges on the backbones of polymer chains, which have a significant impact on polymer solution rheological properties. The negative charges on the polymer backbone repel one another at low salinities and induce the polymer chain to stretch. The negative charge on the backbone boosts the viscosity because of the intermolecular repulsion (Xu et al., 2011). When we are talking about synthetic polymer most of the time, we are referring to polyacrylamides. The performance of a polyacrylamide will generally depend on its molecular weight and the degree of hydrolysis (Sugiharjo et al., 2009). The term polyacrylamide is used to describe any polymer containing acrylamide as one of the monomers (Xiong et al., 2018). The molecular weight (MW) of a commercial polyacrylamide varies from 105 > 107 Da. PAM with high MW (>106 Da) has more applicability because of its high viscosity, water retention characteristics, and drag reduction capabilities.

Partially Hydrolysed Polyacrylamide (HPAM)

The copolymer of acrylamide (AM) and its salts (acrylic acid) is the commercially available water-soluble PAM mostly used in cEOR application; and is known as hydrolysed polyacrylamide or HPAM (Seright et al., 2011; Niu et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2008; Xu et al., 2012; Wakasiki et al., 2014). Partially hydrolysed polyacrylamide (HPAM) for EOR applications, is formed by adding alkali to PAM. HPAM or its salts can be directly produced as acrylic acid and copolymer of acrylamide (Levitt and Pope, 2008). The mechanical entrapment and chemical adsorption can be attributed as the reason for PAM to be adsorbed and also the retention of PAM and other polymers on the reservoir surfaces (Hollander, Somasundaran and Gryte, 1981). However, in some cases, mechanical entrapment is the main reason for the retention of PAM. There are many factors responsible for the adsorption of PAM on the surface of the rock, and this may include temperature, ionic strength, polymer molecular weight, surface charge, and the functional group distribution (Kursun et al., 2000; Sabhapondit, Borthakur and Haque, 2003).

Thermal Stability of Hydrolysed polyacrylamide (HPAM)

The degree of hydrolysis (DOH) is the term used to describe the percentage of acrylate groups in HPAM. The negative charge caused by hydrolysis increases the viscosity of the polymer because of the increased repulsion between the chains of HPAM. However, an elevated degree of hydrolysis may not always be beneficial in all cases, as precipitation may occur in the presence of divalent cations. Zaitoun et al., (1983) reported that, in the presence of divalent cations, at 80ºC, the value for the critical degree of hydrolysis for precipitation to be 33%. Moreover, even if precipitation does not occur, strong interactions of cations with the carboxylate group can lead to a decrease in HPAM viscosity (Zaitoun and Potie, 1983; Ryles, 1988; Lu et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2009). However, according to Ryles (1988), the solution viscosity is very high, when the amount of divalent cations is negligible (< 200 ppm). The rate of hydrolysis is strongly dependent on the pH and temperature (Lu et al., 2010). Ryles (1988), realised that at 90ºC, the rate of hydrolysis is rapid, at 70ºC moderate and 50ºC negligible.

Rheology of hydrolysed polyacrylamide (HPAM)

Hydrolysed polyacrylamide (HPAM) exhibits different behaviours. At low shear rates usually exhibits Newtonian behaviour and at high shear rates non-Newtonian behaviour. A non-Newtonian behaviour includes both shear thickening and shear thinning regions (Nasr-El-Din, Hawkins and Green, 1991; Lewandowska, 2007; Ghannam and Esmail, 1998). The shear thickening behaviour is usually seen after a critical shear rate. The critical shear value generally depends on the degree of hydrolysis, the molecular weight, the temperature and the concentration of polymer (Lewandowska, 2007; Hu, Wang and Jamieson, 1995). Salts considerable decrease the viscosity of HPAM aqueous solutions because of the charge shielding effect (Sukpisan et al., 1998; Martin et al., 1983), but it is still better than non-ionic PAM (Sabhapondit, Borthakur and Haque, 2003). The PAM chain is highly sensitive to shear degradation and very flexible. The inclusion of the acrylate group makes the chain rigid because of the charge repulsion (Flew and Sellin, 1993). HPAM, on the other hand, is less sensitive to shear degradation, when compared to PAM, and HPAM with high molecular weight is more sensitive to shear degradation than HPAM with low molecular weight (Martin, 1986). During pumping and near wellbore region, a high shear rate can be observed. HPAM with high molecular weight also makes it less suitable for low permeability oil reservoir (Zhong et al., 2009). Zaitoun et al., (2012), observed that, some high molecular weight polymers viscosity was low when compared to low molecular weight polymers viscosity after shearing The rheology of salinity sensitive polymers, such as HPAM in aqueous solutions is already well understood (Sorbie, 1991). With increasing polymer concentration and with decreasing salt content, the viscosity of the solution or melt consequently increases. Such solutions may exhibit a shear-thinning behaviour (i.e., the viscosity of the solution decreases with increasing shear rate), for typical shear ranges encountered at the reservoir scale. This behaviour is especially important for the deployment of polymer flooding in the field, as the highest shear rate would be encountered near the wells; and thus, the decrease in viscosity would further enhance the polymer injectivity (Torrealba and Hoteit, 2019).

Adsorption of hydrolysed polyacrylamide (HPAM)

A higher degree of hydrolysis (DOH) reduces the HPAM adsorption in sandstone reservoirs because of the large number of COO− groups in HPAM. In carbonate reservoirs, the adsorption of HPAM is higher than in the sandstone reservoir. Unlike non-ionic PAM, electrostatic attraction between the rock surface of the reservoir and the charged polymer plays a significant role in polymer adsorption. (Atesok, Somasundaran and Morgan, 1988). Therefore, the strong connection between COO− and Ca2+groups results in high adsorption of HPAM in carbonate reservoirs. Salinity also has a detrimental effect on HPAM adsorption in sandstone reservoirs. A very high concentration of salt introduces cations that facilitate the interaction between the polymer and the sandstone rock surface by reducing the size of HPAM flexibility chain, which leads to high adsorption (Lecourtier, Lee and Chauveteau, 1990; Cook, King and Peiffer, 1992; Lee and Lecourtier, 1989). High-temperature results in an increase in the negative charges on the rock surfaces, which increases the electrostatic repulsion and consequently decreases the adsorption. Another important factor that influences the retention of polymers in the reservoir rock is the permeability (Sheng, 2010). Mechanical entrapment is high in low permeability rock and, low in high permeability rock. According to Seright and Zhang (2013), HPAM adsorption and retention in dilute and concentration region has been shown to be concentrated independent, while in the semi-dilute region is concentration dependent. Seright and Zhang (2013), also proposed that polymer retention can be reduced by first injecting a solution with low polymer concentration. Polymer molecules exist as a free coil in the dilute region, and almost all of the molecules are in contact with the surface of the rock. In the concentrated region, the polymer molecules cover all the sites of the rock. Thus, in these two regions, concentration does not affect. There is mixed adsorption in the semi-dilute region, where full segments of the molecules are adsorbed while others are only partially adsorbed. Yun 2014 showed that at higher salinity conditions, HPAM retention for a micromodel system is low. Moreover, Lee and Schlautman (2015), showed that the molecular weight’s effect on polymer adsorption follows a non-monotonic trend, with low adsorption for both high and low molecular weight and moderate adsorption for intermediate molecular weight. According to Jankovics (1965), polymer with high molecular weight would actually adsorb less and more slowly. If the dominant interaction mechanism between the polymer and the rock is the adsorption, and then continue to inject a polymer solution in the reservoir at a salinity lower than the salinity of the reservoir, then low salinity front will be transported ahead of the front of the polymer. This behaviour is called polymer retardation (Lake et al., 2014). In summary, in the presence of divalent cations, the application of HPAM is limited to 75ºC. However, the application of HPAM can be extended to 100ºC, in the presence of negligible amounts of divalent cations (< 200 ppm). Many reservoirs with residual oil tend to have more hostile conditions of salinity and temperature (Chen et al., 1999; Han et al., 2013). It is evident from the above discussion that both PAM and HPAM have deficiencies and requires some modifications or replacement for cEOR in high salinity and high-temperature reservoirs. Several attempts have been made in order to improve the performance of EOR polymers for reservoirs with high salinity and high temperature, by modifying or changing the structure of both PAM and HPAM. For the modification of PAM, several approaches are used. Copolymerisation of acrylamide (AM) is the most common method to extend the application of AM based polymers with suitable monomers that can increase the rigidity and stiffness of the polymer chain (Sabhapondit, Borthakur and Haque, 2003; Khune et al., 1985). Modified PAM can be split into three classes. The first class of PAM consist of those copolymers or terpolymers synthesised by adding rigid or stiff monomers. These monomers are more resistant to cation shielding, more resistant to chemical degradation, and can sterically obstruct the polymer chain to keep the hydrodynamic radius at fair value at high salinity.

Copolymers of Acrylamide

3.3 Copolymers of Acrylamide

3.3.1 Copolymer of Acrylamide and 2-Acrylamido-2-Methylpropane Sulfonic Acid. The thermally stable 2-acrylamido-2-methylpropane sulfonic acid (AMPS) monomer can be copolymerized with AM to obtain a water soluble anionic polymer with improved thermal stability. The structure of AM-AMPS copolymer is shown in Fig. 3. Several investigations of laboratory evaluation of AM-AMPS copolymer for EOR applications92,93 have been reported. Incorporation of the AMPS monomer in AM also improves the solubility of thepolymer in the presence of divalent cations. Thermal stability of AM-AMPS copolymer (Moradi et al., 1987)Thermal stability of AM-AMPS copolymer (Moradi et al., 1987) evaluated the AM- AMPS copolymer with a low AMPS content (36%) at 121◦C. Although precipitation was observed at this temperature in seawater of 33, 560 ppm, increasing AMPS content to 91% showed negligible precipitation. Using a high AMPS percentage has a couple of disadvantages; namely, AMPS is a more expensive monomer compared to AM and the homo polymer of AMPS is not a good viscosifier. They reported the optimum conditions for application of the polymer as a 40% AM content and a maximum of 93◦C at a maximum salinity level of 33,560 ppm. Ryles94 observed that the rate of hydrolysis decreased with increasing AMPS concentration. Parker95 discovered that AMPS itself hydrolyses at temperatures higher than 120◦C with AMPS hydrolysing after 55 days, while at 150◦C

Natural polymers

Xanthan gum is the most important polymer in this class; however, there are others such as carboxymethylcellulose, sclerolucan, welan gum, guar gum, okra, cassava starch, aqueous beans, mushroom polysaccharides, cellulose and schizophyllan. The expression‘gum’according to Zohuriaan and Shokrolahi, (2004), is generally used to refer to a group of polysaccharides (natural polymers) or their derivatives which, when dissolved in water, produce a viscous solution at a low concentration. Gums can be generally categorised as modified gum or natural gum; and by the fermentation of microbial organisms (xanthan, welan) or plan exudate (gum Arabic), natural gum can be obtained. In contrast, modified gums include cellulose derivatives or starch (Zohuriaan and Shokrolahi, 2004).

Xanthan Gum

Xanthan gum can be defined as a high molecular bio polysaccharide, which is typically produced by the Xanthomonas bacterium fermentation process (Leela and Sharma, 2000; Jang et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2012). Xanthan has shown to be tolerant to divalent cations, and, under high salinity conditions can maintain its viscosity (Celik, Ahmad and Al-Hashim, 1988), due to the ordering of molecules of xanthan at high salinities. However, negatively charged pyruvate molecules wrap around the main chain in the presence of salts to make a rigid rod-like structure (Celik, Ahmad and Al-Hashim, 1988). Xanthan gum resistance to shear and mechanical degradation is way better than polyacrylamide because of the rigidity of the chain (Zaitoun et al., 2012; Seright, Seheult and Talashek,2009; Abbas, Donovan and Sanders, 2013). In deionised water, xanthan gum viscosity is lower when compared to polyacrylamide copolymers at equivalent molecular weight and concentration. However, when compared to PAM copolymers, xanthan gum has higher viscosity in salinity solutions (Sheng, 2010).

Thermal Stability of Xanthan Gum

The molecules of xanthan gum at low temperatures comprise of a structure of double helix, while at high temperatures, the structure of double helix is convertedinto a disordered coil (Xu et al., 2012).Ryles et al., (1983), stated the temperature limit for xanthan gum to be < 70ºC, while Ash et al., (1983) stated that xanthan gum was stable at 70ºC. However, Wellington (1983), after studying polymers, he reported that polymers were stable at 90ºC. According to Milas et al., (1988), there is a 50% of viscosity retention at 80ºC after six months, while according to Seright and Henrici (1990), xanthan gum retained 50% of the viscosity for at least five years at 75 to 80ºC. Han et al., (1999), reported xanthan with 60% of viscosity retention for 300 days at 80ºC and 170,000 ppm salts. Under most of the conditions examined, xanthan gum is thermally unstable at 100ºC, and the thermal stability is dependent on the polymer concentration, conformation, and salt content (Lambert and Rinaudo, 1985; Kierulf and Sutherland, 1988). The difference in the temperature limit stated in the studies referred above is probably due to difference in salinities. Xanthan gum’s thermal stability strongly depends on salinity. The results reported show that xanthan solutions are thermally stable at salinities, where an ordered structure is reached by xanthan. For example, a xanthan gum solution having 1 g/L of sodium chloride (NaCl) was not thermally stable at 90ºC due to the disordered structure at this salinity. However, another solution having 50 g/L of sodium chloride (NaCl) was thermally stable at 90ºC because of the formation of an ordered structure at this salinity level (Lund, Lecourtier and Muler, 1990). For EOR applications, this property is highly desirable, and it illustrates the possible application of xanthan gum flooding in reservoirs with high salinity. Xanthan, in general, is not stable at high temperatures (90ºC).

Rheology of xanthan gum

Xanthan gum rheological properties are suitable for EOR applications. In the oil and gas industry, xanthan gum is utilised for the numerous purposes, and this includes drilling, pipeline cleaning and work-over, fracturing, and completion (Kat-zbauer, 1998).Xanthan gum has a non-Newtonian pseudoplastic behaviour at room temperature (Richardson and Ross-Murphy, 1987) and in solution, xanthan exhibits shear thinning, and the viscosity decreases with shear. During pumping and near the well bore area, polymers may experience very high shear. In contrast to HPAM, xanthan gum is more resistant to shear, that is due to the rigid or rod-like structure of xanthan (Abbas, Donovan and Sanders, 2013). The viscoelastic behaviour that HPAM presents is due to chain entanglement, and HPAM chains are unable to relax fast if high shear is applied and breakage may occur. On the other hand, at high shear, rigid rod-like chains of xanthan tend to align with the flow field with minimal breakage (Abbas, Donovan and Sanders, 2013). A very high viscous solution can be obtained because of helical conformation, and it is stabilised by the formation of hydrogen bonds between the backbone and the side chains (Seright, Seheult and Talashek, 2009; Bejenariu et al., 2010). Xanthan gum solutions may even form a liquid crystalline phase at high concentrations (Bejenariu et al., 2010). A small amount of salts added to an aqueous solution of xanthan causes a decrease in viscosity due to the charge shielding effect (Wang et al., 2002; Xu et al., 2012). Increasing the concentration of salts, however, has no major effect on the viscosity. Similarly, with the addition of salts, the dynamic modulus also decreases, but adding more salts has a negligible effect on the dynamic modulus (Xu et al., 2012). In summary, xanthan shows much better rheological properties at high salt concentrations compared to HPAM. Furthermore, the shear resistance is also better when compared to HPAM.

Adsorption of xanthan

Adsorption of Xanthan gum: the electrostatic attraction between the positively charged limestone surface and the negatively charged pyruvate functional group is the main reason for the adsorption of xanthan gum on limestone. Moreover, to determine the adsorption of xanthan gum, one of the most important factors is the pH. The adsorption is considered as high, when the pH is below 8.2 and it decreases with increasing pH above 8.2 because of the negative charge, caused on the surface of limestone rock. Salting out at high salinity is another process responsible for the adsorption of xanthan gum. The presence of salt may decrease or increase the adsorption of xanthan gum. Moreover, above plateau region, the adsorption of xanthan gum increases with adding the salt and vice-versa (Celik, Ahmad and Al-Hashim, 1988). This is because of the competing effects of electrostatic attraction and salting out. Increasing the temperature that allows xanthan gum to coil, helps to reduce the adsorption of xanthan gum on limestone because of reduced exposure of negative side chains of coiled xanthan to rock surfaces (Celik, Ahmad and Al-Hashim, 1988). In the presence of surfactants, the polymer adsorption competes with the surfactant adsorption. Celik et al., (1988), studied the adsorption in the presence of ethoxylated sulfonate and realised that as both polymer and surfactant carry negative charges, a competition exists between the xanthan polymer and the ethoxylated surfactant. From the data he collected, it showed that, the adsorption of surfactant is much faster when compared to the polymer because of the low molecular size of the surfactants. By adding calcium, the adsorption of xanthan gum on the sand was found to increase, (Lee and Lecourtier 1989) and adsorption is controlled by the competition of electrostatic repulsion between xanthan and hydrogen bonding xanthan gum and mineral surfaces. Although the electrostatic repulsion dominates at low ionic strengths and adsorption is low, electrostatic repulsion decreases at high ionic strength, leading to an increase in adsorption. In summary, the adsorption of xanthan gum when compared to HPAM is low (Lee and Lecourtier 1989).

Xanthan gum molecular weight

Xanthan gum has a molecular weight of about 2x106 to 2x107 Da, and xanthan gum having a viscosity of 1g/L is between 13-35 mPa.s and at low pH values (up to pH 3) the viscosity is stable, temperature (up to 80ºC) and high salinity (up to 3% salt).

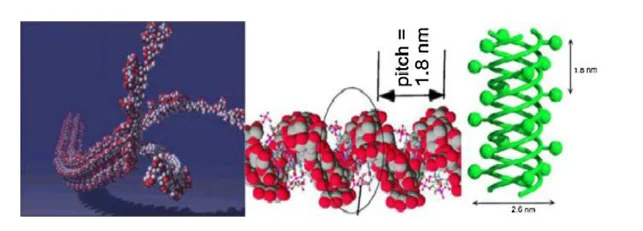

Schizophyllan (SPG)

Schizophyllan (SPG) is a non-ionic and water-soluble extracellular biopolymer, which is produced by the fungus schizophyllum, and it is a white-rot ubiquitous mushroom found in the forests of Germany (Zentz et al., 1992; Quadri, Shoaib and Alsumaiti 2015). Because of its non-toxic, high stability and environmentally friendly characteristics, SPG is used in different sectors and for multiple purposes such as the treatment of cancer, preservation of food and in the oil industry (De Dier et al., 2013; Borchani and Paquot, 2015; Fang and Nishinari, 2004; Zhong et al., 2013). Schizophyllan contains the same structure, as that of the scleroglucan natural polymer (Fang, Takahashi and Nishinari, 2004), consisting of b-(1-3)-D glucose residues linearly linked with one glucose side chain of b-(1-6)-D- for every three main chain residues (Fang, Takahashi and Nishinari, 2004). Figure 6 below illustrates the chemical structure of schizophyllan. The excellent properties of SPG solutions are due to a very stiff triple-helical structure that is formed in the SPG polymer chains (see figure 7).

Schizophyllan (SPG) has an outstanding thickening efficiency, with a high average molecular weight of 2–6 Mio Daltons. Schizophyllan can endure harsh conditions of high salinity and temperature due to its stiff triple-helical structure and intermolecular interactions via hydrogen bonding. In addition, SPG is freely charged, which therefore results in low adsorption on the surface of the rock; and with the increase in salinity and temperature the low adsorption values decreases (Leonhardt, Ernst and Reimann, 2014).

In what concerns rheology, SPG presents quite similar properties to other natural polymers. Showing pseudoplastic fluid behaviour with pronounced shear-thinning and thixotropy properties and can be analysed theoretically by the power-law model. Concentration plays a vital role in SPG solutions performance. Its rheological data in the presence of a low concentration of SPG solutions show substantial viscoelastic properties, while a high concentration, solid-like state arises. In addition to concentration, the viscoelasticity of the SPG solution is highly affected by temperature. (Fang and Nishinari, 2004; Sanada et al., 2012; Ogezi et al., 2014).

Mushroom polysaccharide

Mushroom is a type of fungus, which exists significantly on the earth. It is commonly utilised in medical and food industry, due to its bioactive activities, such as anti-inflammatory and antioxidants activity. Mushroom polysaccharides, commonly referred to as glycans, contributes primarily to the bioactivities of mushroom (Kim et al., 2015; Aves and Do Nascimento, 2016). Based on the number of different monomers, polysaccharides can be divided into two classes: 1. Homopolysaccharides, containing only one kind of monosaccharide; 2. Heteropolysaccharides, including two or more kinds of monosaccharide units. Currently, commercialized mushroom polysaccharides mainly includes schizophyllan, lentinan, grifolan, krestin (polysaccharide epeptide complex) and PSK (polysaccha- ride protein complex) [80,81]. The chemical structure of mush- room polysaccharides varies from diverse origin and culture environments, and generally includes single-helix, triple-helix and random coils. The triple-helical form is usually the most stable conformation [82]. Fig. 11–15 presents the structure of some typical mushroom polysaccharides [79, 83]. The properties of mushroom polysaccharides are closely related to their chemical structure and molecular weight. According to the previous studies, the molecular structure of mushroom polysaccharides, namely the ratio of triple helix to single chain, changes with the molecular weight [84]. For rheological properties, it was reported that, mushroom polysaccharides solutions are pseudo- plastic fluid with shear-thinning properties caused by the orientation of the polymer molecular chain. The orientation degree increased with the shear rate. Moreover, the viscoelasticity of the polymer solution strongly depends on the concentration and temperature for a specific polysaccharide [85–87]. The report of the pilot tests of mushroom polysaccharides EOR are limited and only a field test using schizophyllan was conducted in the Bockstedt oilfield in Northern Germany in 2014 as mentioned above [74].

Okra

Another study on natural polymers was performed by Alamri et al. (2012), they studied okra using the Brookfield rheometer. They discovered that the profile obtained showed an increase in shear stress at a higher shear rate, which confirmed the fluid had pseudoplastic behaviour and conformed with the power-law model. Georgiadis et al. (2010), also had similar findings reporting that okra exhibited a shear thinning behaviour at high concentration. According to Sengkhamparn et al. (2009), while studying pectin in okra, they realised that okra exhibits high viscosity at low concentration and also shows shear thinning behaviour. Ndjouenkeu et al. (1995), also came up with similar conclusions confirming that the flow behaviour of okra was similar to other polysaccharides, showing shear thinning behaviour and an increase in viscosity with concentration.

Welan gum

Welan gum is an anionic natural polymer formed by the fermentation of sugar by the genus Alcaligenes bacteria. Welan gum is commonly utilised in the petroleum industry as a cement addictive, water shutoff chemical and enhanced oil recovery viscosifying agent. As shown in figure below, WLG comprises of a three-fold arrangement of double helices. The terminal a-L-rhamnopyranosyl groups comprise two-thirds of the repeating welan gum units, and the remaining has an a-L-mannopyranosyl group. The properties of welan gum solution are greatly affected by sodium (Na) and calcium (Ca), because of these anionic charges on the backbone (Gao, 2016; Gao 2014). For example, the viscosity and viscoelasticity of welan gum solution reduce when the inorganic cations are present due to the shrinkage and coiling of polymer chains under the charge screening effect (Kaur et al., 2014).In contrast, Gao 2014 conducted the rheology tests of welan gum solutions and observed that, WLG was able to withstand harsh conditions upon long- term heating. The superior tolerance of WLG solution to extreme conditions is mainly attributed to the network structures formed by the adjacent double helices. Owing to the network structure, WLG solutions exhibit higher viscoelasticity and viscosity than xanthan at the same conditions even though WLG has lower molecular weight. For rheological properties, WLG solutions are also typical non-Newtonian fluid with shearing– thinning behaviours (Lopes, Milas, and Rinaudo 1994).

Guar gum

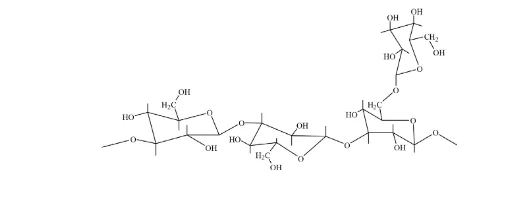

Guar gum is a non-ionic and hydrophilic natural polymer, generated from the endosperm of Cyanaposis psoraloides and two annual leguminous plants Cyanaposis teragonalobus. The majority of Guar gum production in the world comes from India or Pakistan (Razavi et al., 2016; Kobayashi, 2012). Guar gum is commonly used as a thickening agent of fracturing fluid because it is one of the naturally occurring water-soluble natural polymers with the highest molecular weight (Azizov, Quintero and Saxton, 2015). As seen on figure below, Guar gum is composed of (1-4) b-D mannopyranosyl unit of linear backbone chains with a-D-galactopyranosyl unit branch points connected by (1-6) linkages.

Due to the hydrophilic nature, GG is insoluble in organic solvents but attains its full viscosity potential in cold water. In addition, GG possesses good hydration properties because of its large hydrodynamic volume and the nature of specific intermolecular interactions (Asubiaro, Shah, 2008; Ines et al., 2011). Nevertheless, GG is not able to be hydrated completely, which leads to potential risk of plugging in porous media when GG is used as EOR base fluid (Gastone, et al., 2014).The non- ionic nature renders GG compatibility to salts over a wide range of pH value. For the entire shear rate range, the viscosity of GG solution increases as salinity increases mainly because of a fact that the shielding of ionic charges formed by salt ions is disrupted, which thus leads the main chains to expand. However, the salt resistance of GG decreases with the increase of divalent cations and GG may precipitate from solutions at high concentrations of calcium ions (Wang, 2015; Sun and Boluk, 2016). As for temperature effect, the viscosity of GG solutions increase with temperature due to insolubility of some molecule at low temperature and then rapidly decreases with temperature, indicating the poor thermal stability. In terms of rheological properties, GG solutions exhibit Newtonian behaviours at relatively low concentrations and pseudoplastic behaviours at high concentrations. However, the elasticity of GG solutions is weak, and no yield point is observed (Casas, Mohedano and Garcia-Ochoa, 2000).

Nowadays, the petroleum utilised as emulsifier, thickener, and stabiliser in the food and beverage industry and pharmaceutical industry is the biggest consumer of Guar gum and more than 40% of the world’s Guar is used as additives in hydrofracking fluid. It is approximated that a traditional hydrofracking project consumes 80 acres’ annual yield of Guar (200–500 kg/acre). The high demand of Guar in the petroleum industry results in a big export volume of Guar from India to the USA. In 2013, around 800 thousand tons of Guar gum was produced globally, out of which 300 thousand tons were exported from India to the USA [70]. The average MW of Guar gum is in a range of 106 to 2 × 106 Da and the ratio of mannose to galactose units is varied from 1.6:1 to 2:1 [26,27].

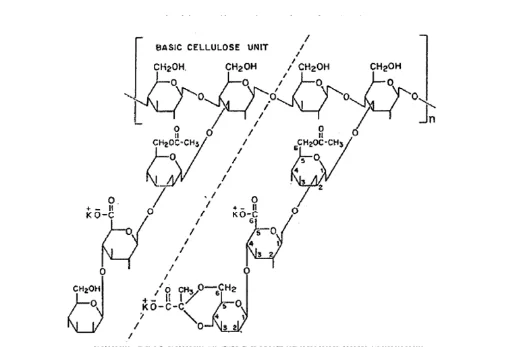

Carboxymenthylcellulose

Carboxymenthylcellulose is an anionic polyelectrolyte produced from the reaction of chloroacetic acid with insoluble cellulose in the presence of base. CMC has a specific gravity of 1.6 and usually exists in the form of white and odourless powder. Wide applications of CMC in food industry, pharmaceuticals and cosmetic industry, textile industry, and oil and gas industry, can be found (Liu et al., 2012; Kowalska and Krzton-Maziopa, 2015). The repeating unit of CMC is anhydro glucose C6H10O5, which is similar to that of starch except that the anhydro glucose units are bonded through b-linkages. The structure of CMC varies depending on the degree of substitution (DS) of the hydroxyl groups on the anhydroglucose unit. Figure 5 below shows the structure of CMC with degree of substitution of 1 (Thomas, 1982). The rheological properties of CMC solutions are highly dependent on polymer concentration. The solutions show nearly Newtonian behaviours at low concentration; while at high-end concentrations, a pseudoplastic, thixotropic and viscoelastic response is observed. Furthermore, CMC solutions exhibit concentration-dependent viscoelastic properties and have a critical concentration c*. Viscous behaviour dominates when CMC concentrations lower than c*; while when the concentration exceeds c*, elastic behaviour is presented. All these properties of CMC solution including pseudoplasticity, viscoelasticity and thixotropy are associated with the heterogeneous substitution of the hydroxymethyl groups. Similar with the above biopolymers, degradation is also a serious concern for CMC. The general limit temperature of CMC is from 135 to 149ºC. In addition to thermal degradation, oxidative decomposition may also occur. The limitations and challenges make the pilot test of CMC injection vacant to date.

Scleroglucan

Scleroglucan is a non-ionic biopolymer produced by the fermentation of a pathogen fungus plant of genus sclerotium. It is currently regarded as the best eco-friendly alternative for HPAM because of its excellent stability and environmentally friendly nature. Scleroglucan has a rigid, rod-like and triple helical structure, consisting of linearly connected b-1, 3-D glucose residues and b-1, 6-D side chain of glucose attached to each third main chain residue in the backbone (Rivenq, Donche and Nolk, 1992; Guo et al., 1999). Figure 12 below shows the illustration of a Scleroglucan structure.

Scleroglucan’s rigid chain and triple-helical structure give rise to its outstanding solution properties, such as good shear resistance and excellent tolerance to temperature. Due to its non-ionic features, scleroglucan solutions are also resistant to pH and high mineralisation. Farina et al., (2001), while studying this topic observed that scleroglucan solutions tended to remain stable when the pH was changed to either moderately alkaline or highly acidic values. Nevertheless, when the triple helical structure decomposed under this extreme condition, a pH above 13 led a steep decline in the apparent viscosity. Moreover, after the addition of NaCl, KCl, CaCl2, MgCl2 and MnCl2, there was a slight decrease in the viscosity of the solution; the presence of FeCl3 however, resulted in an increase in viscosity. The main reason for the decrease in viscosity is because of the gradual interactions within the multi-stranded structure triggered by the inorganic salts. In contrast, the increase in viscosity can result from aggregation and gelation caused by the breakdown of glycosidic linkages FeCl3 is present with pH = 1.3 – 1.5 (Farina et al., 2001). In addition to high stability, scleroglucan solutions display high viscosifying ability at low concentration because of its chain rigidity of the triple helical structure and high molecular weight (Shoaib and Quadri, 2016). According to Davison and Mentzer (1982), liquid grade scleroglucans are good seawater candidate viscosifier with at least a five-fold rise at 90ºC for a concentration of 500 g/m3. Concerning rheological properties, scleroglucan solutions display pseudoplastic behaviour with an exponential relationship between polymer concentration and apparent viscosity.

Scleroglucan

The MW of Scleroglucan is ranged from 1.3 × 105 to 6.0 × 106 Da, varied from different producing strains and fermentation conditions [19]. Scleroglucan disperses easily in the water due to the presence of glucopyranosyl group [66], and 35 mg/L of Scleroglucan can give 10 mPa·s of viscosity. Generally, Scleroglucan possesses better stability than Xanthan under extreme environments, which is a common concern in petroleum production. Kalpakci et al. studied the thermal stability of Scleroglucan at realistic reservoir conditions and found only 10–20 percent of the original viscosity was lost at 105 ◦C after 460 days. Moreover, the Scleroglucan solution can retain all of its viscosity at 100 ◦C during the two years research period [21]. Scleroglucan is recommended to be applied at temperature of up to 135 ◦C while the loss of viscosity occurs in a short time beyond this threshold [22]. The outstanding rheology and stable properties make Scleroglucan the second-largest utilised biopolymer in the petroleum industry, following Xanthan gum.

Cassava starch

Liu et al. (2014) investigated the rheology of cassava starch to manufacture adhesives and stated that with the increase in the speed of the rotor, the apparent viscosity of cassava starch decreased slowly, the fluid was pseudoplastic and it also exhibited shear-thinning behaviour. Che et al. (2008), on the other hand, conducted a series of studies on dilute aqueous solution of cassava starch an found that it also exhibited shear thinning behaviour, and when the concentration was increased above 0.4% the cassava starch changed from Newtonian to non-Newtonian; and to represent the flow behaviour of the fluid three models are suitable, the power law model, Bingham model and Herschel-Bulkley model. according to Huang et al., (2006), the mechanical activation reduces the cassava starch’s apparent viscosity, and this apparent reduction in viscosity with increase in shear rate shows the existence of shear thinning nature.

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts