Dyslexia: Understanding the Reading Disorder and Its Various Definitions

Background by definition:

Dyslexia is considered to be a reading disorder among children and adults. The disorder can be recognized up to a certain limit by understanding the difficulties faced while reading and spelling single-word (Lyon et al., 2003; Pennington, 2009). Dyslexia can be considered to be of neurobiological in origin and have a high chance to get inherited. The risk factors contributing to dyslexia are premature birth, history of the condition in the family, delay in early speech and low birth weight of approximately less than 1500g along with environmental factors upgrade risk for the condition through with early intervention it can be prevented among children (Fletcher et al, 2007, Pennington, 2009). For those seeking education dissertation help, understanding these aspects is crucial in addressing the complexities of dyslexia in academic research. According to initial definition formulated by World Federation of Neurology dyslexia is considered to be a reading disorder in presence of several conditions such as average level of intelligence, socioeconomic status and conventional instruction (Critchley, 1970).

The above definition has been widely criticized because it defined by exclusion criteria, i.e., they have detailed what cannot be considered as dyslexia and failed to provide the inclusion criteria. (Rutter, 1982). Up to date definitions have come up through research which explains dyslexia according to the definition provided by the International Dyslexia Association (IDA) as “difficulties with accurate and/or fluent word recognition and by poor spelling and decoding abilities. These difficulties typically result from a deficit in the phonological component of language that is often unexpected about other cognitive abilities and the provision of effective classroom instruction.” (Lyon et al., 2003). This particular definition has been widely accepted because it has included all the inclusionary criteria and has also specified dyslexia to be a word-level disorder. By definition, it can also be presumed that the disorder is a specific cognitive deficit. There is evidence of sufficient classroom instruction and in the absence of any other disabilities, the intellectual retardation can be well explained followed by no additional reference to socioeconomic status and intelligent quotient (IQ).

The following features that differentiate dyslexia from any other reading disorders are tasks that may involve a) single words decoding (dyslexia), b) the capability to read words and a text automatically in absence of any word that denotes fluency, c) a problem of comprehension when decoding and fluency skills are found to be intact. Therefore a dyslexic person typically features all the problems in all three domains, but small children experience difficulty basically in fluency with or without comprehension. This type of distinction is very much important to identify the neuropsychological and neurobiological problems and its correlation will vary with the character of the reading problem (Fletcher et al., 2007).

Prevalence:

The correct definition of dyslexia used in the study determines the prevalence of the disorder. Based on the definition used it can be considered that about 5% to 10% of the population is dyslexic. Moreover, the nature of the definition estimates the prevalence and it is specific to a particular sample group used in the study. As per literature survey prevalence can be estimated to be about 6 to 17% in the school-age children which depend upon the criteria that have been included for understanding the severity of the reading disorder (Fletcher et al., 2007). Male predominance is evident from the data showing the ratio of about 1.5:1 which is lower than historical approximation showing the ratio of about 3–4:1 (Pennington, 2009; Rutter et al., 2004).

Signs and Symptoms of Dyslexia:

According to author (Moats et al, 2010) who identified the symptoms of dyslexia stated that the primary signs and symptoms are wrong and slow printing and word recognition, extremely poor spelling sense which in turn affects the reading accuracy and fluency, facing difficulty while reading comprehension and compromised speed of processing capabilities (reading fluency). Moreover according to the author (Olagboyega et al, 2008) the characteristics of dyslexia varies with discrepancy observed with ability and level of work produced, their intelligence and capability to learn, facing problem with the retrieval of the word, the problem with the speed of reading, memory problem, speed of processing, etc. They face problem to break down words morphologically. They cannot even spell an easy word, a prominent feature of dyslexia. Regarding spelling difficulties he explained in details about the misinterpretation of sound like using of ‘pad’ for ‘pat’; He also mentioned about writing spelling with wrong boundaries such as ‘firstones’ for ‘first ones’ writing wrong syllabification, such as ‘rember’ for ‘remember’; mentioning wrong duplication of letters such as ‘eeg’ for ‘egg’; application of intrusive vowels like ‘tewenty’ for ‘twenty’ confusion about the use of ‘b’, ‘d’ such as ‘bady’ for ‘baby’; and occurrence of letter reversal such as in ‘lentgh’ for ‘length’ or ‘tow’ for ‘two’. According to several authors, the dyslexic candidates feel quite different from their peers because of their compromised learning ability.

The Morton’s Model or Causal Model for Dyslexia:

According to the definition of the British Dyslexia Association (BDA, 1996) dyslexia is considered as a complex neurological condition and the condition affects more than one area such as difficulties are faced while reading, writing and spelling. The other areas such as numeracy, musical skills, functions of the motor and the organisational skills are sometimes affected due to this disorder. Morton and Frith (1995) used the phrase “causal model” to illustrate the foundation of the disorder. The model explains the cognitive and biological origin of the developmental disorder and related records are maintained of the varied range of description related to the biological, cognitive and the behavioural aspects. A definite space is kept for the environmental factors that shows interaction with the above mentioned all three levels. When the biological level is considered the gene factors, the condition of the brain and the causal relationship between the two are elaborated. The model also allows explaining the conditions of the environment such as the complications associated with the birth and the complications of the brain. The cognitive domain includes both the affective and the cognitive factors. The affective factors are generally placed at the intermediate cognitive levels but both Morton and Frith also highlighted that these effects can also be explained at the biological level as a physiological reaction or at the behavioural effect in the form of facial expression. The behavioural expression of the disorder are also stated and based on these it can be estimated that where the causal flow of the model finally approaches for example the condition of “poor reading”. These factors are considered to be of developmental significance. Therefore this model provides a explanation for the disorder as an integration of cognitive and the biological factors and also gets influenced by the environment (Morton, and Frith, 1995).

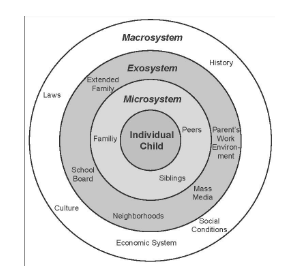

The Ecological Model:

This perspective is concerned with the position of the child within the families and the social or the cultural context. Based on few suggestions, the ecological paradigm can become favourable for two reasons: 1) It helps in the amalgamation of the related areas responsible for the developmental and social psychology. 2) Perspective identifies number of factors which influences the development of children. Therefore, the ecological paradigm includes all the factors concerning the development of the child and this has been elaborated by the model of Urie Bronfenbrenner. The perspective explains that the child and the environment get influenced by each other in a bidirectional, mutual and transactional manner. Therefore, this approach takes into account of the influences of the home and school (microsystem) and the cultural or political context (macrosystem). Based on the factors, one can freely consider the social and the developmental factors to design an educational policy identifying the needs and desires of children. The change becomes possible only with the widening of the assessment and this does not allow a child to be referred as dyslexia recognizing the failures of the children. Instead of that all children should be constantly observed and evaluated so that they are being taught in a manner that justifies their needs and at the same time recognizes the abilities. Particularly this approach is desirable as at present it is also recognised that a child with dyslexia has a genetic origin and the educational practice has to be altered without discriminating them (Poole, 2003; Ryan, 2001).

Other theoretical perspectives related to dyslexia:

Phonological theory:

This theory explains that individuals with dyslexia suffer from a deficiency in the representation with respect to the storage and repossession of the sounds of the speech. The capability of concentrating and influencing the linguistic sounds and this is very much essential for development and mechanization of the graphophonic relation required for the skills of coding and decoding the phonologic sounds. The deficiency in the phonological aspects represented by the dyslexic individuals results in an uncertain and dishonoured phonological representation. When the sounds of the speech are poorly retrieved, stored and presented then the learning concerned with the graphophonic is severely compromised. Those who advocate this theory they give consent over the causal part of the phonological deficit among the dyslexic individuals. The theory is supported by the evidence that the dyslexic individual have poor performance in relation to the phonological awareness, segmentation and management of the speech sounds (Prestes, and Feitosa, 2016).

Allophonic Theory:

This theory particularly stresses upon the fact that individuals who are dyslexic depicts a change on their perception of speech. The representation of phonemic is considered to be the ultimate stage in the process of development and it can be categorised into two important stages such as: the incorporation of the allophonic characteristic within the special phonologic characteristic of language which occurs when the individual is only one year old. The other aspect is the inclusion of the phonological characteristics within the segments of phonemic and this happens when the individual is between 5 and 6 years old. The atypical perception of speech can be considered as the major cause of dyslexia which specifically disturbs the principle of understanding. That is the reason why even the transparent alphabetical systems turns dense for the individuals who are dyslexic. This is also the major reason behind the alteration of the phonological awareness as it disturbs the mental picture of the phonemes. But this theory also faced criticism because it did not address or disregarded the findings related to the non linguistics deficits among the dyslexic individuals such as the deficiency in the auditory perception (Prestes, and Feitosa, 2016).

Auditory Deficit Theory

This theory is based on the fact that the auditory deficit is the major cause for the alteration caused during the phonological deficiency which causes difficulties during the reading, learning and writing. This theory depicts that the auditory deficit is the principle cause and the phonological deficit is considered to be the secondary one. The stimulus of speech is an acoustic signal and any alteration in the processing of auditory temporal domain eventually results in difficulties in the dealing with short elements for example with the consonants. Therefore any change in the observation of short sounds along with the rapid transitions of the auditory stimulus causes difficulties in the understanding of speech and have a negative impact on the formation of mental picture of stimulus of speech. The graphophonic writing is the coding and decoding of the stimulus of graphic which depicts sounds. The process of learning requires the capacity of the integration the auditory and the visual graphic component. Though several authors have criticised this theory based on the evidence that not every dyslexic individual faces problems or alteration in their temporal processing (Prestes, and Feitosa, 2016).

Psychological Impact of Dyslexia:

Thomson et al, 1990, has stated that the word dyslexia is purely scientific and medical. In light of this theory, dyslexia depicts “difficulty” or malfunctioning in reading or writing. The issue of dyslexia is much broader in the scenario than what we see it as “reading failures”. When a child goes to school there is always an expectation from him regarding his studies, to see him read and write well. Every child learns at his level and pace, and every child is different from the other in terms of their ability and skills. Unfortunately some children fall below expectation, and this is where learning difficulties come into play. It appears to be very much disturbing to parents and teachers when coming across a child who is very intelligent in many other areas but facing problems with reading, learning, and obviously, the matter becomes a serious concern. An individual without any knowledge of dyslexia refers to the child as not being intelligent. Crabtree, 1975 believes that there should not be any negative approach while dealing with children and instead of that it should be replaced with a more constructive, organised and more positive approach. Dealing with a dyslexic person is a matter of responsibility and patience. Dyslexia compromises the learning capability of child and it weakens the confidence level of the child when he sees other non-dyslexic children of her type and age progressing in the class work especially on the side of reading, writing and learning. Therefore to raise awareness among all age group people, sincerely the government and educational stakeholders should organise seminars, workshops on dyslexia and its implications. The programme of enlightenment will definitely reduce the incidence of labelling a child, and there should be a clear set goal in the school curriculum for the dyslexic individuals in the schools. Those children deserve love and care like any other child. Equility Act, 2010 views dyslexia as a condition of specific learning difficulty; many individuals who are with dyslexia have noticeable visual, creative problem-solving skills. Dyslexia should not be linked to intelligence, makes learning difficult, it is rather a “learning disorder”. It is worthy of note that, people who have dyslexia are often smart and hardworking, but have many troubles in connecting the letters they see. Dyslexia could be observed in children with both high and low intelligent quotients.

General George Pattern (1885-1945) the one time president of United States of America during the period of world war confessed that “he was not able to acknowledge letters till he became nine years old; at that same time he was also not able to read and write till he became eleven years old “.We should also understand that it is hard for individuals who are afflicted with dyslexia to spell correctly and if he cannot spell, it is more difficult to express in papers. This has been a hard task for those who went to school as dyslexic pupils or students like “George Patton” whom we have referred to in our explanation. Many problems come with word dyslexia. Dyslexia is a disorder which manifests specific learning difficulty (SLD) in which the person faces difficulties with reading and writing of language and words. Most of the dyslexic people manifest these characteristics, though it varies from day to day, they are consistent; they have excellent long-time memory regarding past experiences, locations and faces of people (Edwards, 1993; Emily et al, 2018).

Impact of Dyslexia on Reading and Writing:

To achieve academic development, lifelong learning capability and for sustainable development one should possess the highest ability to learn, read and write (Trudell et al, 2012). However, people suffering from dyslexia will find it difficult to accomplish this target as they face the problem in reading writing and learning. According to Regents of the University of Michigan, 2016, mentioned in their recent research report that the condition dyslexia makes it difficult for the learners to acquire the skills which are extremely crucial for learning process such as fluency in reading, spelling, following written directions, sequencing of information, spelling and access to certain text. Moreover, dyslexic individuals are forced to compensate for their weakness by following the other people of their age group, processing verbal information and also using note memorisation and also using experimental learning context. In a study conducted by Asiko, the chief executive of the non-profit Strive International that one out ten people are dyslexic. This is the reason behind about 5 million South Africans who are struggling with learning problems in school and other workplaces. Children suffering from dyslexia go through mental problems as they get abused by their peers at their school environment because of their inherent learning ability.

Environmental Factors Associated with dyslexia:

Conditions such as poverty, the orientation of family towards literacy acts as risk factors for dyslexia. Poverty has a clear impact upon language and achievement, but in case of middle-class families also where one or both of the parents are poor readers no importance can be given to learning-related activities (Pennington et al., 2009). However, another critically important factor is instruction. Through classroom-based approach has been undertaken to train dyslexic individualsthe quality of instructions varies considerably. The Meta-analytic reviews, for example, National Reading Panel Report (NICHD, 2000) have shown that children facing reading problems need instructional approaches which are plainer, such as the conversion of the alphabetic principle into training through methods like phonics (Rayner et al., 2002). In addition to teaching phonics more wide-ranging approaches that may also comprise reading practice to enhance fluency and clear teaching of comprehension strategies including vocabulary results in enhanced levels of overall proficiency of reading (Stuebing et al., 2008). The earlier intervention results in better outcomes; this is because children could not match with their peers when they are unable to contact print (Torgesen et al., 2001).

The other co occurring conditions with dyslexia:

It is common that people with dyslexia also suffers with learning disorders which are called co-occurring difficulties such as dyspraxia and the attention deficit disorder. The common features of dyslexia and dyspraxia are the difficulties in the processing of short term memories, while following the instructions, during concentration, in the sense of direction and sequencing, while copying from the board. The core problems of dyspraxia are poor tone of the muscle, the awareness of the body, in the integration of sensory elements, during motor planning. The common difficulties associated with the ADHD are inconsistency, organisation of the memory. The core problems are difficulties associated with the attention, hyperactivity and the impulsive behaviour. Another associated co occurring condition is the specific language impairment where the individual faces problems with regard to the receptive language and expressive language. They also show the features of short time related memory, during the planning and organisation, while following the instruction and the phonological awareness (Muter, and Likierman, 2008).

Diagnosis:

Diagnosis of dyslexia is a major problem as there is no specific blood test or any brain imaging technique available that can provide an accurate diagnosis. Author (Ellis et al, 1984) summons a medical correspondence while discussing dyslexia that reading in backward direction can be considered as a graded thing similar to physical ailments like obesity and measles. There has to be a solid basis before dividing the population into dyslexic and non-dyslexic. The differentiation should be based on quantitative measurements for the differentiation of dyslexic and non-dyslexic. While discussing the subjective author (Shaywitz et al, 1992) highlighted that their study findings stated that dyslexia can’t be stated as an all-or- anything phenomena and its severity varies in degrees like hypertension and obesity. Clinicians must understand there is practically no value of the cutoff score assigned in the aspect of biological activity and these are only assigned as the resources are limited.

Primarily, the technique that is used to diagnose the disorder that reading is calculated on a scale though no cutoff score is considered to be accurate which could differentiate individuals into dyslexic and nondyslexic groups. The distinction cutoff that differentiates between dyslexia and normal reading is subjective; the cut off considered varies from one study to another and therefore it is controversial. The situation, therefore, indicates that some subjectivity is needed to diagnose people suffering from dyslexia disabilities and the importance of a single isolated word reading test can be well understood. The Woodcock-Johnson Word Identification subtest or the Wide Range Achievement Test is used to distinguish dyslexic patients. During the test procedures in both the tests, the individual is advised to read words that will increase in difficulty (for example change over from simple words to complex multisyllable words like ‘cat’, ‘emphasis’ and ‘idiosyncrasy’). After the completion of the tests, the individual test scores are compared within the same age group. As mentioned in the Woodcock Word Attack test, pseudoword reading can be considered to be a significant test for the dyslexic patient. During the test reading of letters of pronounceable combinations which do not symbolize English words but can be expressed using English pronunciation rules are used for example items such as ‘shum’, ‘bab’, ‘bafmotbem’, ‘cigbet’. This test determines the decoding skills as possessing this skill helps to learn, read and ascertain the pronunciation of new words never encountered before.

Genetic and Neurological Basis of the disorder:

Dyslexia is of genetic in origin and it run in families has a genetic basis, and it is clear that dyslexia tends to run in families. Premature birth, history of the condition in the family, delay in early speech and low birth weight of approximately less than 1500g are the risk factors associated with the condition. Research studies on dyslexia have highlighted several chromosomes that may contain the necessary gene or genes responsible for dyslexia. The accurate genetic mechanism behind the disability and the pattern of inheritance are still not known. Studies on family (Pennington et al, 1991; Pennington et al, 1997; Pennington et al, 1999; Schulte-Korne et al, 1996; Snowling et al, 2000; Fisher et al, 2002; Regehr et al, 1988) have led to the discovery of the participation of definite chromosomes (Fagerheim et al, 1999; Fisher et al, 1999; Gayán et al., 1999) which point towards the genetic constitution of dyslexia. Chromosomes number 6 and 15 are thought to be of concern regarding the genetic basis of dyslexia. Although environmental factors can have ameliorating effects upon the condition, the basis of genetics can define the condition (Castles et al, 1999). Phonological dyslexia is a condition where individuals face more troubles while reading pseudowords was found to be more heritable than orthographic dyslexia, where individuals face more troubles reading exception words in a study conducted by Castles et al (Castles et al, 1999). Both types of disorder demonstrated considerable heritability.

As the genetic basis, there is also a neurological basis for dyslexia. As evident from the post mortem studies abnormalities have been found in the brain structure of dyslexic individuals (Galaburda et al, 1979; Galaburda et al, 1985). There is an absence of usual asymmetry in the planum temporale as a universal finding as neurological findings. The profound structural difference in the corpus callosum, which controls the communication between two hemispheres of the brain, has been observed between dyslexic and non-dyslexic individuals (Robichon et al, 1998; Robichon et al, 2000).

Treatment Available:

Direct and systematic way of teaching letters and their corresponding sounds (known as phonological skills) is an important way to treat dyslexic patients. As mentioned by Hatcher (Hatcher et al, 2003) and Nicolson et al, 1999 programs that methodically teach individuals the sounds of the letters found to be successful. Children with reading difficulties designed programs to augment reading fluency have improved reading abilities as per Vaughn et al (Vaughn et al, 2000). To improve the decoding skills and reading skills of dyslexic children Lovett et al (Lovett et al, 1988; Lovett et al, 1989; Lovett et al, 1990) and Vellutino et al, 1987) found a training programme for word recognition and decoding skills. Computer-based programs are very helpful in these cases. A study conducted by Wise et al (Wise et al, 1989) showed that computers can help dyslexic children. Reading books on a computer linked with speech synthesizers and then obtaining feedback on words that they found to be difficult was found to be an efficient way of learning. The approach also improved the children’s attitude towards learning. Computer-based exercises which influence speed or automatization helps to improve the reading skills of dyslexic individuals as mentioned in a study conducted by Irausquin et al. To nurture the reading skills of dyslexic children a computer speech based program was used by Lovett et al (Lovett et al, 1994; Lovett et al, 1994). Besides training the dyslexic children it is also important to know about the talents of the children. They are found to be gifted in the field of sports, art, music and dance and other may have superior visuospatial skills (Wolff et al, 2002). The skills can be found to be useful in the career of architecture and engineering.

Prevention:

Reading difficulties of children can be identified within five years of age (in kindergarten) and therefore required intervention programs can be provided. Study of Lesaux and Siegel, et al, 2003, found that children found to be at risk of reading difficulties in kindergarten level, when provided with classroom-based intervention programs which enhances phonological awareness, reading strategies and vocabulary (Wolff et al, 2002).

Updated news on Dyslexia:

Rather than labelling children as dyslexic making them eligible for special education services is highly appreciated. The model is named as Response to Instruction identifies children with difficulties and provides them with a classroom-based approach, more academic interventions which help them to overcome their difficulties. Following this model may prevent the condition or lower the serious learning problems of the children. This model is considered to be less costly and also patient-friendly. The research study of the future should focus on those children who cannot correct their single word deficiency after repeated interventions than those typical at risk considered children as discussed above. These studies will focus on the neurobiological and neuropsychological factors and will be of interest to neuropsychologists. Concept about the relation between brain dysfunction and neuropsychological tests may need to be subjected to change as according to newer concepts dyslexia is a heritable disorder which poses a greater threat to brain. Identification based on neuropsychological tests as a central part of identification is not well considered. Classification research should simplify the identification process. Moreover, very few evidence are available that such kind of assessment improves the academic and adaptive results. On the contrary little evidence are available upon Aptitude × Treatment interactions for identifications of cognitive/neuropsychological skills during treatment (Hale et al, 2008). Most relevant evidence about Aptitude × Treatment interactions is when strength and weakness related to academic skills are utilized to provide instruction differentially (Connor et al, 2007).

DEVELOPMENTAL COORDINATION DISORDER (DCD):

Background:

Major advancements have been noticed for understanding brain development and behavioural disorder though the study is not accompanied by a literature review of traditional academic infrastructure. The constant barriers faced in this field are disciplinary isolation and absence of significant interdisciplinary opportunities. For the enhancement of the clinical practice, researches and to train the subsequent generations academic institutions need to take courageous steps which will challenge the traditional departmental boundaries. These changes are urgently needed to bring truly developing, more organised and efficient approach for treating disorders related to developing brain. To define developmental disorder one should understand the limitations faced in areas of core functional domains such as (such as communication, motor, academic, social) resulting due to anomalous development of the nervous system. The manifestations of the limitations can occur during the infant stage and childhood featured as delay in approaching the developmental landmark, abnormalities that can be considered as qualitative and also lack of functions observed in more than multiple areas. Deficiency in multiple disciplinary boundaries defines the disorder and this makes the condition as a subject of potential interest to neurologists, psychiatrists and psychologists. Clinicians from other disciplinary subjects of health such as paediatrics working on developmental-behavioural characteristics, occupational and physical therapists and speech and language disorder pathologists also take this as a subject of immense interest. The clinical manifestations of the developmental disabilities show considerable differences in severity and also in certain areas of dysfunctions. Children suffering from developmental disorder get often affected in multiple spheres of function because of the various reasons such as non-specific nature of the condition and degree of abuses during the time of maturation of brain or augmented susceptibility to several causes resulting in disability such as trauma, malnutrition, infection. The characteristic feature of developmental disorders is an abnormal development of the brain in one or more spheres of function at the time of childhood but the reasons behind other brain disorders are not currently included and they may have their foundation in early anomalous neurodevelopment (Reiss et al, 2009). This can be well understood with the help of the mental disorder schizophrenia, which often demonstrates itself as in-depth symptoms of illusions and figment of the imaginations especially during the phase of late adolescence and early adulthood, is considered to have its roots in earlier childhood (Raedler et al, 1998). Early symptomatic features include delicate deficits of sensory-motor system, abnormalities observed during socialization, learning disabilities and also non-specific behavioural patterns. With the advancement of sensitive biological markers and specific early diagnosis, several treatments have materialized in the path of clinical neuroscience and therefore this disorder will be considered as neurodevelopmental in origin. The disorder is considered as the neurological condition which affects the attainment of certain skills such as memory, attention, language, and social interaction (Reiss et al, 2009). The disorder has a genetic origin but it is very difficult to detect the presence of the disorder through standard genetic screening of the parents. That is why the mutation noticed in an affected child can be considered as “de novo mutation” (DNM). Based on research it can be estimated that more than 40% of the developmental disorder is due to de novo mutations and it is equivalent to 1 out of 295 births in the United Kingdom alone. Moreover, the increase in prevalence is observed with increasing age of the parents. This kind of disorder become more distinct during childhood and includes conditions such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability and Rett syndrome. The features may be mild in some cases but some cases can show severe features and may require lifetime support system. Unfortunately when the disorder cannot be identified then providing the child with the best care is very much difficult (European Society of Human Genetics, 2019).

Prevalence

The prevalence of DCD is estimated to be as high as 10% and due to this, the disorder is referred to as a “hidden problem” (BBC Health Dyspraxia, 2006). 6 % can be considered to be more appropriate, among them 2% can be considered to be severe and a figure of 10% denotes individuals affected at a moderate level. The data implies that most of the school classes will consist of at least one affected child. As per data males get affected four times more frequently than females (Gordon et al, 1980) Premature birth and very low birth rate are the risk factors highly associated with the condition.

Characteristics of Developmental Disorder:

The clinical manifestations of dyspraxia differ considerably among children. Some may be noticed during infancy while some others manifest itself at a certain level of life. It varies from individual to individual and depending on the onset of the condition. Several problems may get unnoticed on the normal setting but when they are assigned a task which involves more than one child the symptomatic features may get noticed. The disorder can manifest itself in several ways among children and if not properly handled with care then can cause a wide range of problems for the children. The disorder exerts its inhibition on the normal maturity level and activities of the children. At first symptoms of dyspraxia can be noticed in a child with the problems of not sitting, crawling, and walking through these activities are common for children at their age and does them comfortably. Parents who are observant enough will notice his or her unusual body position which shouldn’t be in the first place. This child finds it difficult to play or manipulate his toys especially with the ones that have some complexities. The child faces problems such as “ lack of proper coordination of his body”, feeding the child also becomes difficult most times, the child cannot make use of spoons and knife during eating, this is because of the skills that are involved. Dyspraxic child does not have proper awareness of his body parts and also they don’t have proper control over their senses. Children suffering from developmental disorder always have a concentration problem. The child does not have proper control over its body parts and also lacks the power of judgement most of the times. Individuals affected with the disorder when becomes old their symptoms worsen and their life gets compromised. Dyspraxic children generally found to avoid certain physical activities such as jumping, football, running and other complex activities (Gordon et al, 1980).

Diagnosis:

For an accurate diagnosis of DCD, a vigilant neurological examination is required which should investigate for signs of cerebellar, a peripheral neuromuscular and other central neurological or connective tissue disorder. Both hearing and vision assessment should also be included in the examination. Subsections on Motor skill assessment of standard developmental assessment schedules should be used to measure coordination. The various other schemes developed are predominantly useful for the assessment of motor coordination (Touwen et al, 1979; Denckla et al, 1985) which also includes the Bruininks–Oseretsky Test determining the Motor Proficiency. The short version of this test takes only 30 minutes to administer when compared to the full version which takes about 2hours (Bruininks et al, 1978). In the United Kingdom the most widely used assessment is the Movement Assessment Battery for Children (Henderson et al, 1992) Moreover paediatric therapist rather than paediatricians including the neurodevelopmental paediatricians are more familiar with these motor assessment.

Further Assessment:

For the assessment of DCD and its associated complication a team of the paediatrician or paediatric neurologist along with physiotherapist and occupational therapist plays the major role and they, in turn, involve educational, clinical or neuropsychologists for the evaluation of associated difficulties. However the availability of all these specialized personal is unlikely though their contribution can be of immense help to those affected with DCD. After the initial diagnosis by the paediatricians and paediatric neurologists, it is a part of their responsibility to refer the cases for such an assessment. It cannot be considered as an appropriate practice to refer to every child suspected to be “clumsy” or “awkward”. This is because many children suspected of having DCD historically when referred for such assessment to an occupational therapist it was observed that their motor skills were actually within the normal limit. Therefore many cases which have been referred to occupational therapists are considered to be inappropriate ones which depicts significant waste of resources and mentioned as inefficiency within the National Health Service (Dunford et al, 2004) This can be well related with the fact stated in a recent survey consisting of 134 paediatric occupational therapists working in United Kingdom mentioned that out of the total cases that has been referred to occupational therapy services only 30.4% cases of the children were affected with DCD (Missiuna et al, 2006; Missiuna et al; 2004).

As an alternative approach other than occupational therapists and physiotherapists who are supposed to assess all suspected coordination difficulties help can be demanded from nursery or primary school staff, health visitors. Instead of those children who are more severely affected and demonstrates considerable coordination difficulties during their late preschool and early school years should be referred to occupational physiotherapy for proper evaluation and therapeutic regime. The children who are less severely affected manifest the symptoms at a later stage when no reference is needed to limited and overextended occupational and physiotherapy services. Doctors or Medical officers of school are in the ideal position of assisting and identifying any school children and they should be encouraged to take up the suspected cases of DCD. They should also enquire about the other notable features to the school staff such as about the motor performance of the children, problems during attention control, generalised or specific difficulties associated with learning and how the child relates to or get mixed up with their peers. A further report from any educational psychologist about the involved child will be highly appreciated. Several children suffering from coordination difficulties may not have a certificate from an educational psychologist but the assessment demands the need for that support for those children involved. The Motor Skill Screening Test was developed by Portwood as a screening instrument, and it is considered to be appropriate for the teachers to use as it takes only 20 minutes to administer. The Weschler Intelligence Scale for Children Revised is used by an educational psychologist can help to enhance this screening test. This particular test can be considered to be more official in addition to developmental background primarily helps the child in their classroom setting. Basic data have also suggested that teacher and parent intervention immensely helps children with DCD (McWilliams et al, 2005). Standardised questionnaires namely Perceived Efficacy and Goal Setting System which includes teacher and a caregiver questionnaire tool could be used for this kind of assessment (Missiuna et al, 2006; Missiuna et al; 2004).

Causes of Dyspraxia:

Researchers stated that the reason behind dyspraxia is not clearly understood and there are many researchers all over the places, trying to ascertain the root cause of dyspraxia in children. It is observed that among children facing movement difficulties have immature neurone development. Some experts believe that the nerves which control the area of muscles fail to develop appropriately and therefore, the brain itself cannot function properly. It is believed that there is an interruption within the region of the brain from where the information gets transferred from the brain to the body. Therefore it grossly affects the individual’s ability to perform activities in a very smooth coordinated way. However, because of the disorder occurred due to both dyslexia and dyspraxia it is advisable to make necessary interventions which will help them during their growth (Gordon et al, 1980).

Discussion about few Developmental Disorders:

Autism:

Among the different categories of prevalent developmental disorders, autism and its diagnosis have become a matter of great interest for both people who are conducting research and common public. Children suffering from autism can reveal a wide range of clinical features which includes developmental abnormalities which are qualitative, nerve-related problems especially related to sensory/motor symptoms, cognitive dysfunction, epilepsy, serious complications regarding adaptive behaviour and abnormal regulation of emotions. As a common man perspective, the disorder autism can be considered as an unfathomable disorder hindering childhood development. Although primarily the concept about the disorder was viewed as a disorder developed due to faulty parenting, at present the newer concept has cleared all doubt that autism happens as a result of abnormal brain development, function and has a genetical background (Reiss et al, 2009).

Rett syndrome

Rett syndrome (RS), is considered as a significant aetiology for intellectual disability and developmental deterioration among young females. The frequency of the condition is 1 in 10,000 live girl childbirths. The disorder shows clinical manifestations which need the expert guidance of clinicians, especially neurologists, paediatricians specialized on developmental-behavioural patterns, and psychiatrists. Psychologists expertised in both clinical and behavioural training plays an important role by helping the affected child along with her family after the onset of the clinical manifestations. Rett Syndrome also has a strong genetical origin therefore intervention from medical geneticists are also participating increasingly to diagnose the condition with precision. The initial symptoms of RS may at first get noted by a paediatrician and then the paediatrician may refer the case to a neurologist or specifically to a specialist of developmental disorders for further improvement and diagnosis. The vital signs and indications of the disorder include delayed development after birth but the pathology is not similar for all the cases as many individuals achieve the normal or close to normal accomplishment of an early developmental target during the initial weeks and months of their life. Other symptomatic features include suboptimal head growth during infant stage while communicating deterioration or stagnation of their hand use occurs especially around 1–2 years of age, other notable involuntary movements with hand stereotypy and irregular inhalation and exhalation process. Muscle tone also gets reduced during the early stage of development and the impairment increases over time. The previous symptoms when accompanied by deterioration and developmental plateau, the affected child may lose previous build up skills and interest regarding outspoken behaviours. This particular time can be considered to be crucial for the diagnosis of autism and intervention from psychiatrists or psychologists are demanded. After the phase of developmental deterioration as mentioned above, the track of RS becomes more stable, as a slow trajectory of developmental and cognitive growth can be observed with the ongoing establishment. Among 50% of affected person generalized motor or partial seizures can be observed (Reiss et al, 2009).

Fragile X syndrome:

Fragile X syndrome (FXS), is an X-linked semi-dominant disorder and considered to be one of the most common inheritable neurodevelopmental dysfunction. The literature study revealed that the disorder is prevalent up to 1 out of 4,000 males and 1 out of 8,000 females (Crawford, et al, 2001). Abnormal development of the brain and its functions leads to a chain of behavioural, cognitive, emotional and neurological problems which in turn occurs due to reduction in FMRP from full mutations linked with the identification of FXS (Reiss et al, 2003). Due to consistent inactivation of X chromosome, the condition is most prevalent among females. All males and about 50% of females demonstrate notable cognitive symptoms. It has also been observed that few FXS affected males and females consist of a mixture of cells showing a varied range of repeats (also known as repeat mosaicism) and because of this reason a huge range of phenotypic features can be noticed among individuals who are affected. Before the onset of puberty, fragile X syndrome of boys typically bears large heads and after attaining puberty, the traits may become more unique such as typical long face having prominent jawline and huge ears, forehead and macroorchidism.

Treatment Available

Therapeutic program for DCD includes certain well-designed trails. Generally, therapists use two major methods for treatment for DCD (Miyahara et al, 1995). The task-oriented approach uses patience as a tool to improve the quality of the task. Whereas in case of process orientated therapy it focuses on development of sensory modalities engaged in motor performance, for example, the sensory integration approach (Ayres et al, 1987) or kinaesthetic (also known as movement perception) approach (Laszlo et al, 1993) Very few studies based on the task orientated approach revealed noteworthy improvements concerning motor skills, as these tasks specifically targeted on this approach (Revie et al, 1993). The benefit achieved by using the task of process orientated therapy is varied, and it is very much similar to the general stimulation programme (Sims et al, 1996) and is much better than any other alternative treatments (Polatajko et al, 1995).

The recent therapeutic regime should also concentrate on developing the self-esteem of the affected individual other than concentrating on the core problems on coordination. Some clinical setups have come up with a better idea to help children to meet the rising educational and physical demand during their movement from primary to the secondary level of education by offering transitional programmes. Apart from physical therapies provided to DCD patients, immense benefit can be achieved from psychological support provided to them in group forms so that they can work upon their motor impairment, lost self-esteem and can develop certain strategies to deal with the problems. Handfuls of therapists residing in the United Kingdom are successfully trained with this kind of assessment and treatment approaches related to sensory integration. Therapists who have substantial expertise in this arena may use a wide range of non standardised tasks to evaluate the ability of the child in certain areas which includes cerebral integration, motor skills, limb-girdle stability, kinaesthetic awareness and body awareness.

Children and adolescents suffering from coordination difficulties demand treatment accuracy, and for them searching for care and help can be a matter of extreme frustration for families (Peters et al, 2004; Rodger et al, 2005) DCD affected children faces substantial level of difficulties at school level and therefore to educate the educators about this kind of condition is an indispensable part of the therapeutic regime. All should work in a team and they should be aware of the social consequence of the disorder.

Take a deeper dive into Divergent Views on Adverbs: A Comparative Analysis with our additional resources.

References:

- Lyon GR, Shaywitz SE, Shaywitz BA (2003). A definition of dyslexia. Annals of Dyslexia.;53:1–14.

- Pennington BF (2009). Diagnosing learning disorders: A neuropsychological framework. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; New York.

- Fletcher JM, Lyon GR, Fuchs LS, Barnes MA (2007). Learning disabilities: From identification to intervention. Guilford; New York.

- Critchley M (1970). The dyslexic child. Charles C. Thomas; Springfield, IL.

- Rutter M (1982). Syndromes attributed to “minimal brain dys-function” in childhood. The American Journal of Psychiatry;139:21–33.

- Lyon GR, Shaywitz SE, Shaywitz BA (2003). A definition of dyslexia. Annals of Dyslexia;53:1–14.

- Rutter M, Caspi A, Fergusson D, Horwood LJ, Goodman R, Maughn B, Moffitt TE, Meltzer H, Carroll J (2004). Sex differences in developmental reading disability. New findings from 4 epidemiological studies. The Journal of the American Medical Association; 291: 2007–2012.

- Moats L., Carreker S., Davis R., Meisel P., Spear-Swerling P.M.L. & Wilson B (2010). Knowledge and practice standards for teachers of reading, The International Dyslexia Association: Professional Standards and Practice Committee, Baltimore, MD.

- Olagboyega K.W (2008). The effects of dyslexia on language acquisition and development, Akita International University, Akita City, Japan.

- Trudell B., Dowd A., Piper B. & Bloch C. (2012). Early grade literacy in African classrooms: Lessons learned and future directions, Association for the Development of Education in Africa.

- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Report of the National Reading Panel (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; NIH Publication No. 00-4769.

- Rayner K, Foorman BR, Perfetti CA, Pesetsky D, Seidenberg MS (2002). How psychological science informs the teaching of reading. Psychological Science in the Public Interest; 2:31–74.

- Stuebing KK, Barth AE, Cirino PT, Francis DJ, Fletcher JM (2008). A response to recent re-analyses of the National Reading Panel Report: Effects of systematic phonics instruction are practically significant. Journal of Educational Psychology;100:123–134.

- Torgesen JK, Alexander AW, Wagner RK, Rashotte CA, Voeller KKS, Conway T (2001). Intensive remedial instruction for children with severe reading disabilities: Immediate and long-term outcomes from two instructional approaches. Journal of Learning Disabilities; 34:33–58.

- Ellis AW (1984). Reading, writing, and dyslexia: A cognitive analysis. London: Eribaum.

- Shaywitz SE, Escobar MD, Shaywitz BA, Fletcher JM, Makuch R (1992). Evidence that dyslexia may represent the lower tail of a normal distribution of reading ability. N Engl J Med; 326:145–50.

- Pennington BF (1991). Genetic and neurological influences on reading disability: An overview. Reading and Writing 3:191–201.

- Pennington BF, Siegel LS (1997). Dimensions of Executive Functions in Normal and Abnormal Development. In: Krasnegor NA, Goldman-Rakic PS, editors. Development of the Prefrontal Cortex: Evolution, Neurobiology, and Behaviour. Baltimore: Paul H Brookes Publishing; pp. 265–281.

- Pennington B (1999). Toward an integrated understanding of dyslexia: Genetic, neurological and cognitive mechanisms. Dev Psychopathol;11:629–54.

- Schulte-Korne G, Deimel W, Muller K, Gutenbrunner C, Remschmidt H (1996). Familial aggregation of spelling disability. J Child Psychol Psychiatry; 37:817–22.

- Snowling M, Bishop DV, Stothard SE (2000). Is preschool language impairment a risk factor for dyslexia in adolescence? J Child Psychol Psychiatry;41: 587–600.

- Fisher S, DeFries J (2002). Developmental dyslexia: Genetic dissection of a complex cognitive trait. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience; 3:767–80.

- Regehr SM, Kaplan BJ (1988). Reading disability with motor problems may be an inherited subtype. Pediatrics; 82:204–10.

- Fagerheim T, Raeymaekers P, Tonnessen FE, Pedersen M, Tranebjaerg L, Lubs HA (1999). A new gene (DYX3) for dyslexia is located on chromosome 2. J Med Genet;36:664–9.

- Fisher SE, Marlow AJ, Lamb J, Maestrini E, Williams DF, Richardson AJ (1999). A quantitative-trait locus on chromosome 6p influences different aspects of developmental dyslexia. Am J Hum Genet; 64:146–56.

- Gayán J, Smith SD, Cherny SS, et al (1999). Quantitative-trait locus for specific language and reading deficits on chromosome 6p. Am J Hum Genet;64:157–64.

- Castles A, Datta H, Gayan J, Olson RK (1999). Varieties of developmental reading disorder: Genetic and environmental influences. J Exp Child Psychol; 72:73–94.

- Galaburda AM, Kemper TL (1979). Cytoarchitectonic abnormalities in developmental dyslexia: A case study. Ann Neurol; 6:94–100.

- Galaburda AM, Sherman GF, Rosen GD (1985). Developmental dyslexia: Four consecutive individualswith cortical anomalies. Ann Neurol; 18:222–33.

- Robichon F, Habib M (1998). Abnormal callosal morphology in male adult dyslexics: Relationships to handedness and phonological abilities. Brain Lang;62:127–46.

- Robichon F, Bouchard P, Demonet J, Habib M (2000). Developmental dyslexia: Re-evaluation of the corpus callosum in male adults. Eur Neurol;43: 233–7.

- Hatcher PJ (2003). Reading intervention: a ‘conventional’ and successful approach to helping dyslexic children acquire literacy. Dyslexia;9:140–5.

- Nicolson RI, Fawcett AJ, Moss H, Nicolson MK, Reason R (1999). Early reading intervention can be effective and cost-effective. British Journal of Educational Psychology; 69:47–62.

- Vaughn S, Chard DJ, Bryant DP, et al (2000). Fluency and comprehension interventions for third-grade students. Remedial and Special Education;21:325–35.

- Lovett M, Ransby MJ, Barron RW (1988). Treatment, subtype, and word type effects in dyslexic children’s response to remediation. Brain Lang;34:328–49.

- Lovett MW, Ransby MJ, HardwicK N, Johns MS, Donaldson SA (1989). Can dyslexia be treated? Treatment-specific and generalized treatment effects in dyslexic children’s response to remediation. Brain Lang; 37:90–121.

- Lovett M, Benson N, et al (1990). Individual difference predictors of treatment outcome in the remediation of specific reading disability. Learning and Individual Differences;2:287–314.

- Lovett M, Warren-Chaplin PM, Ransby MJ, Borden SL (1990). Training the word recognition skills of reading disabled children: Treatment and transfer effects. J Educ Psychol; 82:769–80.

- Vellutino FR, Scanlon DM (1987). Phonological coding, phonological awareness, and reading ability: Evidence from a longitudinal and experimental study. Merril-Palmer Quarterly;33:321–63.

- Wise B, Olson R, Anstett M, et al (1989). Implementing a long-term computerized remedial reading program with synthetic speech feedback: Hardware, software, and real-world issues. Behav Res Meth Instrum Comput; 21:173–80.

- Lovett MW, Barron RW, Forbes JE, Cuksts B, Steinbach KA (1994). Computer speech-based training of literacy skills in neurologically impaired children: A controlled evaluation. Brain Lang;47:117–54]

- Lovett MW, Borden SL, DeLuca T, Lacerenza L, Benson NJ, Brackstone D (1994). Treating the core deficits of developmental dyslexia: Evidence of transfer of learning after phonologically- and strategy-based reading training programs. Dev Psychol;30: 805–22.

- Wolff U, Lundberg I (2002). The prevalence of dyslexia among art students. Dyslexia; 8:34–42.

- Lesaux NK, Siegel LS (2003). The development of reading in children who speak English as a second language. Dev Psychol; 39:1005–9.

- Hale JB, Fiorello CA, Miller JA, Wenrich K, Teodori AM, Henzel J (2008). WISC-IV assessment and intervention strategies for children with specific learning disabilities. In: Prifitera A, Saklofske DH, Weiss LG, editors. WISC-IV clinical assessment and intervention. 2nd ed. Elsevier; New York. pp. 109–171.

- Connor CM, Morrison FJ, Fishman BJ, Schatschneider C, Underwood P (2007). Algorithm-guided individualized reading instruction. Science;315:464–465.

- Raedler TJ, Knable MB, Weinberger DR (1998). Schizophrenia as a developmental disorder of the cerebral cortex. Current Opinion in Neurobiology;8:157–161.

- BBC Health Dyspraxia (2006). https://www.bbc.co.uk/health/conditions/dyspraxia2 (accessed 9 Jan 2006)

- Gordon N, McKinlay I (1980). Helping clumsy children. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

- Touwen B (1979). Clinics in Developmental Medicine. Examination of the child with minor neurological dysfunction, 2nd edn, No. 71. London: MacKeith Press.

- Denckla M B (1985). Neurological examination for subtle signs (PANESS). Psychopharmacol Bull 21773–800.

- Bruininks R H (1978). Bruininks‐Oseretsky test of motor proficiency examiner's manual. Circle Pines, Minnesota: American Guidance Service.

- Henderson S E, Sugden D A (1992). Movement assessment battery for children. London: The Psychological Corporation.

- Dunford C, Street E, O'Connell H. et al (2004). Are referrals to occupational therapy for developmental co‐ordination disorder appropriate? Arch Dis Child 89143–147.

- Missiuna C, Polatajko H (1994). Developmental dyspraxia by any other name: are they all just clumsy children? Am J Occup Ther 49619–627.

- McWilliams S (2005). Developmental co‐ordination disorder and self‐esteem: do occupational therapy groups have a positive effect? Br J Occup Ther 68393–400.

- Missiuna C, Pollock N (2000). Perceived efficacy and goal setting in young children. Can J Occup Ther 67101–109.

- Missiuna C, Pollack N, Law M (2004). Perceived efficacy and goal setting system (PEGS). San Antonia TX: Psychological Corporation.

- Crawford DC, Acuna JM, Sherman SL (2001). FMR1 and the fragile X syndrome: Human genome epidemiology review. Genetics in Medicine;3:359–371.

- Reiss AL, Dant CC (2003). The behavioral neurogenetics of fragile X syndrome: Analyzing gene–brain–behavior relationships in child developmental psychopathologies. Development and Psychopathology;15:927–968.

- Miyahara M, Möebs I (1995). Developmental dyspraxia and developmental coordination disorder. Neuropsychol Rev 5245–268.

- Ayres J A, Mailoux Z K, Wendler C L W (1987). Developmental dyspraxia: is it a unitary function? Occup Ther J Res 793–110.

- Laszlo J I, Sainsbury K M (1993). Perceptual‐motor development and prevention of clumsiness. Psychol Res 55167–174.

- Revie G, Larkin D (1993). Task‐specific intervention with children reduces movement problems. Adapted Phys Activity Q 1029–41.

- Sims K, Henderson S E, Morton J. et al (1996). The remediation of clumsiness. II. Is kinaesthesis the answer? Dev Med Child Neurol 38988–997.

- Polatajko H J, Macnab J J, Anstett B. et al (1995).A clinical trial of the process‐orientated treatment approach for children with developmental co‐ordination disorder. Dev Med Child Neurol 37310–319.

- Sugden D A, Chambers M E (2003). Intervention in children with developmental coordination disorder: the role of parents and teachers. Br J Educ Psychol 73545–561.

- Peters J M, Henderson S E, Dookun D (2004). Provision for children with developmental co‐ordination disorder (DCD): audit of the service provider. Child Care Health Dev 30463–479.

- Rodger S, Mandich A (2005). Getting the run around: accessing services for children with developmental co‐ordination disorder. Child Care Health Dev 31449–457.

- Miles E. (1995) can there be a single definition of dyspraxia?”Dyspraxia: an international journal of research and practice,1(1).

- Thomson M (1990). Developmental Dyslexia: studies in disorder of communication (3rd edition).Whurr Publishers LTD. London.

- Crabtree T(1975). Letter to the Guardian 30th December.

- Equality Act (2010): Employment law Guide Acceptance-paperback

- Edwards J (1993). The Emotional Effects of Dyslexia, Studies in Visual Information Processing, North-Holland. Volume 3;Pages 425-433

- Emily M. Livingston, Linda S. Siegel & Urs Ribary (2018) Developmental dyslexia: emotional impact and consequences, Australian Journal of Learning Difficulties, 23:2, 107-135.

- Reiss AL (2009). Childhood developmental disorders: an academic and clinical convergence point for psychiatry, neurology, psychology and pediatrics. J Child Psychol Psychiatry;50(1-2):87-98.

- European Society of Human Genetics. "Developmental disorders: Discovery of new mutations." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 16 June 2019.

- Poole, J., 2003. Dyslexia: a wider view. The contribution of an ecological paradigm to current issues. Educational research, 45(2), pp.167-180.

- Ryan, D.P.J., 2001. Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory. Retrieved January, 9, p.2012.

- Morton, J. and Frith, U., 1995. Causal modeling: A structural approach to developmental psychopathology.

- Prestes, M.R.D. and Feitosa, M.A.G., 2016. Theories of dyslexia: Support by changes in auditory perception. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 32(SPE).

- Muter, V. and Likierman, H., 2008. Dyslexia: A parents' guide to dyslexia, dyspraxia and other learning difficulties. Random House.

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts