Needs of Transgender Students in Athletics and School Environments

- 16 Pages

- Published On: 02-12-2023

Introduction

Athletics and physical education are fundamental components of school children’s experience. Educators acknowledge that the group of students who identify as transgender require adequate attention to ensure that they get the opportunity to enjoy the benefits of physical education participation in a respectful and safe environment (Howe, 2012). Many transgender students, just like their cisgender (i.e. those whose gender identities are the same as the same sex they were assigned at birth) counterparts, enjoy their participation in athletics or physical education classes and therefore, it is the school leader’s responsibility to create an inclusive environment through policies and practices that enable all the students to enjoy and benefit the same experience. For those seeking education dissertation help, addressing inclusion and safety in physical education settings is crucial for supporting diverse student needs effectively.

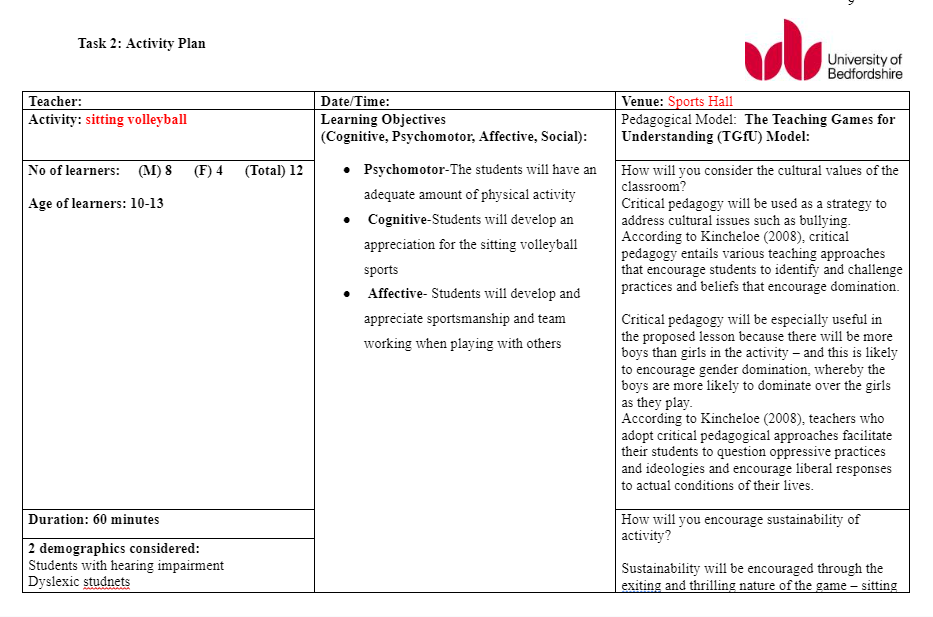

It is until this kind of inclusive environment is created that physical education can be considered inclusive. This essay considers both transgender and minority muslim demographics and examines whether sport or physical education in volleyball is inclusive for these two demographics. To effectively achieve this objective, the essay will rely on a case study of Jasson Anne, who has been a student at a single-sex girl’s school for five years. Jason’s parents disclosed to the headteacher that their child was trans and is under the care of Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS). He had been living as Jason throughout the summer holidays, feeling a lot more comfortable with himself and wanting to continue in his role in the sixth form. Hormone therapy has caused Jason’s appearance to become increasingly masculine, which is occasionally surprising people who are unfamiliar with his transition. On the other hand, Halima is a Muslim girl who likes to participate in Volleyball games.

The concept of inclusivity

The concept of inclusivity has largely been debatable and confused with that of integration. In the education context, Gibson (2014) stated that “Inclusion is political, a transformative process for all participants. Social justice, acceptance and promotion of diversity in the form of its practice.” (pp. 34). On the other hand, Vickerman (2012) defined an integrated class as a setting whereby students from different backgrounds, some with various disabilities learn alongside their peers without disabilities. In an integrated classroom, the disabled students receive extra support to help them adapt to the regular curriculum and in some cases, separate educational programs are implemented within or outside the classroom. However, while both inclusion and integration are geared towards facilitating an enabling environment for students with special education needs to learn, there has been a trend for most educationists to move away from integration and towards inclusion (Armour, 2014).

The whole concept of inclusivity in physical education is anchored under various government policies, laws and regulations that regulate equality, equity and inclusivity within the education sector. In this regard, Hodge (2009) noted that many schools may not have any policies that guide the inclusion of both cisgender and transgender students in sports and physical education and that many physical education teachers may not be aware of the laws, policies and regulations that exist. Yet, over the past few decades, the UK government had adopted numerous laws, regulations and policies that apply to the inclusion of transgender and those from minority ethnic groups (e.g. Halima and Anne) in sports and physical education participated by their non-special education needs counterparts.

For example, the Equality Act of 2010 was enacted to protect individuals from various forms of discrimination, including ethnic and gender-based discrimination. A year later, the Public Sector Equality Duty (2011) was introduced to ensure that the two demographics like Anne are not discriminated against based on her gender, race, disability maternity and pregnancy, sexual orientation and religion. Moreover, other education-based laws and policies that protect Anne and Halima from exclusion include, the Special Education Needs (SEN) and Disability Act 2001 that protects individuals from unfavorable treatment due to their transgender or ethnic identity. Furthermore, the SEND Code of Practice (2014) obliges Anne’s and Halima’s teachers to create a learning environment where individuals with special education needs, just like the others with no special needs, are treated with respect, dignity and equality.

Bearing in mind the legal requirements for inclusivity in the context of sports and physical education, it is only through the adoption of best practices that Anne’s and Halima’s teachers can claim to have established an inclusive volleyball physical education program. Otherwise, that physical activity cannot be considered as ‘inclusive’. According to Evans et al (2015), the best practices may span from school inclusive policies to simple things like establishing gymnasiums, locker rooms, playing fields and other spaces that facilitate inclusivity for transgender and Muslim students.

Looking for further insights on Learning Environment With Planning? Click here.

The first and perhaps the most important aspect of inclusivity that determines if the environment is inclusive for transgender and Muslim students is lesson planning and delivery. According to Haycock & Smith (2011), physical education can only be considered inclusive if the teachers plan their sports and physical education activities in a manner that does not create a barrier to Anne and Halima’s participation and enjoyment of the lessons, just like their non-special needs counterparts. For instance, in line with the SEND Code of Practice (2019), all the facilities in the physical education environment should be accessible – including the showers, locker rooms and toilets. In this regard, Drury et al (2017) pointed out that in a physical education environment, the toilets, locker rooms and showers should be adopted to accommodate both Muslim and transgender students’ identity. This implies that even though Halima and Anne should not use separate facilities, the school should provide private/separate charging spot, toilet and showering facilities when either of the two students request for it. Even the locker rooms should have some private options for toileting, showering or charging for use by Anne and Halima if they desire them. According to Foley et al (2016), this would increase Anne’s and Halima’s enjoyment, confidence and will to participate.

In some cases, teachers plan to have sports and physical activity competition in other schools and venues, and this presents a challenge for transgender and Muslim students. In such a scenario, those sports and physical activities can only be considered inclusive if, for example, Anne’s and Halima’s teachers or coaches, in consultation with both students, should notify their counterparts in the other schools before the competitions about providing appropriate access to toileting, showering and charging facilities that are safe and comfortable for Anne and Halima. However, as McGuire et al (2010) contend, this notification would be done in a manner that maintains Anne’s and Halima’s right to confidentiality.

The other potential area that should be identified and addressed beforehand is the issue of hotel rooms when Anne and Halima travel to participate in physical activity outside her hometown. According to Russell et al (2010), transgender and Muslim students should be assigned their hotel rooms just like their non-special needs counterparts. In doing the hotel bookings, priority should be given to comfort and privacy, especially when the teammates are asked to share rooms.

Physical education can only be inclusive when teachers adapt their teachings to respond to the needs and strengths of every pupil. In terms of language, teachers must ensure all the names and pronouns used within the classroom context is adapted to Halima and Anne’s needs. For example, teammates, students, coaches and any other participant in the volleyball physical education activity must call Anne and Halima by their chosen names. Similarly, as Snapp et al (2015) noted, references to transgender and/or Muslim students should be done in a manner that reflects their pronoun and identity references – same to their non-special needs’ counterparts.

The above proposals for best practices mainly involve modifying the sports environment and activities to meet the needs, abilities and skills of all participants, in this case, transgender, Muslim and non-special need participants. However, according to Williamson & Sandford (2018), there is a general assumption that the best and only way to create an inclusive opportunity for physical education setting is to change various aspects of the standard or regular activities – the common athletics activities always delivered in schools. And yet, it is important to understand that there are many different options encompassed in modifying physical activities in a wide range of settings. To further explain this concept, Fitzgerald (2009) argued that much as adapting or modifying physical education is not always about just including the person in the sports setting without making any adaptation, it is also not just about making minor changes in the physical education activities – even though this is a good place to start.

Against this backdrop, the England Athletics Inclusion Spectrum guidance was developed to facilitate a guided approach to modification and adaptation of sports and physical activities and make them more inclusive. Ideally, it is only until Halima and Anne’s teachers refer to the Inclusion spectrum model and align their physical education lesson plans to the model that they can be inclusive.

Briefly, the inclusion spectrum model has five elements that must be considered to ensure physical education is inclusive: the first element is the open activity element, whereby the teachers are supposed to ensure that their physical education lessons contain simple activities that are based on what both the transgender and Muslims studnets can do without making any drastic modifications (Laker, 2002). For example, if Halima, Anne and her colleagues are to participate in a ball game, the game should be one like volleyball that they can easily play with little or no modification.

The next element of the inclusion spectrum is activity modification. Here, according to Lumby (2016), everyone should do the same activity regardless of the modifications to support and challenge both the transgender and Muslim participants. For example, in case the teacher modifies the volleyball game to make it more enjoyable, everybody should then be allowed to enjoy the game.

Third, the inclusion spectrum stipulates that the physical activities must be grouped according to their abilities, whereby each of them does the same activity but at different levels (Seach, 2011). Again, for example, when Anne, Halima and their non-special needs colleagues are playing volleyball, the teacher should organize each team in a manner that considers their abilities. i.e. mix the students with more skills together with those with less skills – regardless of their gender or religious orientation.

Practically, the inclusion spectrum has several implications for Anne, Halima and her non-special needs colleagues’ engagement in physical education. They must consider several other aspects of the game such as dress code and uniform for the volleyball activity to be regarded as inclusive. For instance, during the game or when they are travelling to the venue, Anne’s teacher must ensure that they have a religious and gender-neutral` dress code (Flintoff et al, 2008). Instead of requiring girls in the team to wear skirts, the teacher should just ask the team to wear slacks or skirts that are clean and dressier to appropriately represent the team and the school.

On the other hand, all the team members should have a uniform that is appropriate for the sport and to all the members – one which they can comfortably wear. Because Anne is a transgender boy who has not undergone surgery to remove her breasts but is competing in a boys’ team, provisions should be made on her uniform to cover her chest while not giving her any competitive advantage over the others (Oliver & Kirk, 2016). On the other hand, because Halima would want to maintain her Hijab while playing, she should be allowed to wear it whenever she feels like.

Based on a broader spectrum of physical education, several other considerations must be made to ensure Anne and Halima receive inclusive physical participation. For example, within the school setting, all members of the school community should be informed about Anne’s transgender identity and Halima’s Muslim religious background (Youndell, 2005). They should receive an orientation education on transgender laws and policies including how to use the appropriate name and pronouns when addressing Anne and Halima. Moreover, according to Azzarito & Soloman (2005), they should also be sensitized on how to interact with Anne in any setting, including the need to set high expectations for every pupil, including Halima and Anne. More importantly, the activities cannot be considered as ‘inclusive’ if the opposing teams, their teachers and coaches are not informed about Anne’s transgender identity and Halima’s Muslim orientation before the competition and the expectations for treatment whenever the teams are off the field.

Looking for further insights on Navigating the Waves of Online Group Communication? Click here.

References

Pedagogical cases in Physical Education and Youth Sport. London: Routledge

Azzarito, L. and Soloman, M. A. (2005) A reconceptualization of physical education: The intersection of gender/race/social class. Sport, Education and Society, 10(1): 25-47.

Drury, S., Stride, A., Flintoff, A. & Williams, S. (2017) Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender young people’s experiences of PE and the implications for youth sport participation and engagement. Sport, Leisure and Social Justice, 84.

Evans, A.B, Bright, J.L & Brown, L.J. (2015). ‘Non-disabled secondary school children’s lived experiences of a wheelchair basketball programme delivered in the East of England’. Sport Education and Society, 20(6), 741-761

Foley et al. (2016) Including Transgender Students in School Physical Education. Journal of PE, Recreation & Dance. 87(3) 5-8.

Fitzpatrick, K, and Russell, D. (2015) On being critical in health and physical education. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 20(2): 159-173.

Fitzgerald, H. (2009). Disability and Youth Sport. London: Routledge (electronic) Stidder, G. and Hayes, S. (ed.) (2013). Equity and Inclusion in Physical Education and Sport. 2nd edn. London: Routledge

Flintoff, A., Fizgerald, H. and Scraton, S. (2008) The challenges of intersectionality: researching difference in physical education. International Studies in Sociology of Education, 18(2): 73-85.

Fittipaldi-Wert, J. and Mowling, C. M. (2009) ‘Using Visual Supports for Students with Autism in Physical Education’. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance, 80(2), 39-43.

Flintoff, A, Fitzgerald, H. and Scraton, S. (2008) ‘The Challenges of intersectionality: researching difference in physical education’. International Studies in Sociology of Education, 18(2), 73-85.

Green, K. (2008). Understanding Physical Education. London: Paul Chapman (electronic)

Laker, A. (ed.) (2002). The Sociology of Sport & PE: An Introductory Reader. London: Routledge Falmer.

Howe, P. D. and Parker, A. (2012). ‘Sport, disability and celebrity culture’. Celebrity Studies, 3(3), pp. 270-282.

of Disability, Development and Education, 56(4), pp. 401-417.

about inclusion and teaching students with disabilities’. International Journal

Lumby, J. (2016). Leading for Equality: making schools fairer. London: Sage (electronic)

Vickerman, P. Walsh, B. and Money, J. (2004). ‘Planning for an Inclusive Approach to Your Teaching & Learning’, in Capel, S (ed.) Learning to Teach PE in the Secondary School: a companion to school experience. London: Routledge, pp. 156-162.

Morley, D. et al. (2005). ‘Inclusive PE: teachers’ views of including pupils with special educational needs and/or disabilities in PE’. European Physical Education Review, 11(1), pp. 84-107

mainstream secondary physical education: A revisit study. European Physical Education Journal Review (to be printed and reflects on Morley et al. 2005 research).

McGuire, et al. (2010) ‘School climate for transgender youth: A mixed method

investigation of student experiences and school responses’, Journal of youth

and Adolescence, 39(10), 1175-1188.

Oliver, K. L. and Kirk, D. (2016) ‘Towards an activist approach to research and advocacy for girls and physical education’. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 21(3), 313-327.

Snapp, et al. (2015) ‘Students’ perspectives on LGBTQ-inclusive curriculum’ Equity & Excellence in Education, 48(2), 249-265.

Seach, D. (2011) ‘Children with Autism’ Chp. 6. In Supporting Inclusive Practice Edited by G.

Smith, A. (2004). ‘The inclusion of pupils with special education needs in secondary school physical education’. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 9(1), 37-54

Russell, et al. (2010) ‘Safe schools policy for LGBTQ students and commentaries’, Social Policy Report, 24(4), 1-25.

Stride, A. (2014) Let US tell YOU! South Asian, Muslim girls tell tales about physical education. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 19(4): 398- 417.

has entitlement and accessibility been realized? Disability & Society, 27(2), 249-262

Vickerman, P. (2007). Teaching Physical Education to Children with Special Educational Needs. Abingdon: Routledge.

Williamson, R. and Sandford, R.A. (2018) ‘‘School is already difficult enough...’: Examining transgender issues in physical education.’

Youdell (2005) ‘Sex-gender-sexuality: how sex, gender and sexuality constellations are constituted in secondary schools’. Gender and Education, 17(3), 249-270.

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts