To Gather the Views of fellow Somali Students on the Factors

Introduction The study aimed to examine the views of young women of Somali heritage undergoing education in the United Kingdom and determine the factors they consider have impacted their academic attainment. The study has looked at various issues that have been the cause of or reasons behind the underachievement among young Somali women, highlighting the need for education dissertation help. The study found that young women and children of Somali heritage studying in the UK are underachieving mainly because of the language barrier. The young girls who come into the UK with the dreams of pursuing education find difficulty understanding the curriculum or teachers because of their inability to communicate, read, write or hear the English language. Additionally, young Somali women in UK schools, similar to other students from ethnic minority groups, are affected with stereotyping because of their skin colour and backgrounds, often seen as second class citizens who are not allowed access to high standards of education and services. Young Somali girls also come from households that experience economic deprivation, often characterized by low income or lack of employment. The economic deprivation affects their households through the lack of proper housing and overcrowding in their residential houses and areas. (Hammond, 2013) The lack of these basic needs or good quality facilities and livelihood is often the cause of stress and anxiety that reduces their focus on their academic attainment, leading to poor performance. This research has also found that most UK schools have failed to use black teachers or achieve workforce diversity, meaning few teachers understand the girls’ needs or cultures. Similarly, the schools have failed to develop inclusive curriculums and ethos for individuals from ethnic minority groups. Lastly, the schools lack monitoring and mentoring programs, and together with the low expectations from these students, they find it difficult to do well in institutions that do not care for their welfare and needs (Bigelow, 2011).

Abstract

The study aimed to examine the views of young girls of Somali heritage undergoing education in the United Kingdom and determine the factors they consider have impacted their academic attainment. This research used mixed methods, both qualitative and quantitative research methods, to find data and relevant issues related to this topic. An online questionnaire and zoom focus meetings were especially used in focus groups to collect relevant research questions. The collected data was then analysed thematically to assess the issues highlighted by the focus groups. Some of the issues raised by the focus groups that seem to affect the attainment of young women of Somali heritage include language barrier, stereotyping and racism, economic deprivation, low expectation, poor housing and overcrowding. Other barriers to excellent performance in the UK schools included lack of workforce diversity or black teachers in some of the schools, lack of monitoring and mentoring programs, and the absence of an inclusive curriculum and ethos (Alitolppa‐Niitamo, 2004). This study has confirmed that some UK schools have continued to produce poor academic attainment among ethnic minority groups. Underachievement, especially among the young women of Somali heritage, is still a concern that communities, schools and policymakers should consider. The research has recommended the development of strategies that can help raise women’s achievement in UK schools, for instance, through strict policies and laws that fight racism and stereotype behaviours in schools and communities, policies that enhance workforce diversity and diversity in communities and institutions as a whole and creating programs that support individuals from ethnic minority groups to perform better in UK education systems (Alitolppa‐Niitamo, 2004).

Literature Review

Diriye and McLean (2006) note that the UK's underachievement or education attainment debate has mostly been about black ethnic minority group students. This author notes that school attainment of young Somali students lags behind their majority peers’ average achievement and that this performance gap is continuously growing both in secondary and primary education. This author claims that despite the increasing concern among policy makers and debate concerning underachievement in UK learning institutions, the young Somali women and students’ needs are yet to be addressed and are instead often overlooked by national and local policymakers because usually, these authorities have failed to identify and recognise Somali heritage individuals in their regions as an ethnic group during the collection of data. Somalis have lacked this recognition in UK societies since the 19th century, yet certain local authorities comprise large Somali ethnic communities (Bahadar et al., 2014). Bahadar et al. (2014) call this situation ‘social invisibility’, an experience that Bahadar et al. (2014) says that even African Caribbean individuals in the UK do not have because they are a recognised ethnic group. Harris (2004) claim that while both African Caribbean and Somalis suffer racism, the previous group is seen as part of the UK community, giving them a significant public presence and visibility in the larger British society. However, even though Somalis are visible through their unique dressing code, the social distance between the British culture and Somalis increases the isolation of this ethnic minority group in the UK (Harris, 2004).

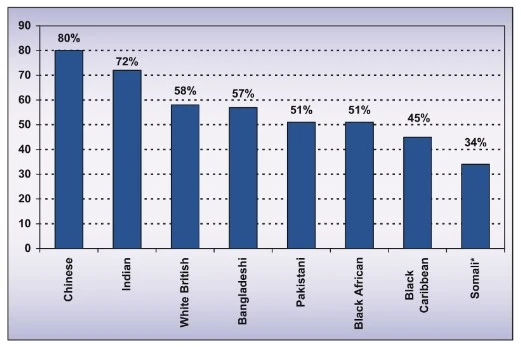

Available evidence conducted in Lambeth, London, shows an increasing pattern of underachievement among students of Somali heritage compared to the average of Indian, Caribbean, African, White British students (Demie and McLean, 2006). Rutter (2004) support this claim by showing the GCSE, KS3, KS2 and KS1 data trend that indicates the dismal academic attainment of students of Somali heritage in 2006.

Diagram 1: Low academic attainment by Somali students in Lambeth schools in London in 2006 (Demie and McLean, 2006). This DfES collected data shows the performance of more than 1000 students of Somali heritage in about 10 UK Local Authority schools (Demie and McLean, 2006).

According to Demie and McLean (2006), various reasons or factors can be attributed to the low academic attainment among students of Somali heritage in these UK schools. One of these factors is that students of Somali heritage have no understanding of the education system in Britain. Demie and McLean (2006) claim that in the UK, students pass through stages based on their age, unlike in their home country Somali where they do so based on their ability. These authors argue that even their parents do not know how the levels, for instance, 1-8, work as a measure of the student’s progress. This leads to confusion among this ethnic group, making both the parents and their children less invested in the education system and their children’s academic attainment. The other issue that these authors discuss is the language barrier. They claim that bilingualism is usually a new idea to many Somali heritage students and their parents. Most of them cannot speak English, and the families have limited capacity or ability to help the young students with school work. Demie and McLean (2006) also suggest that the language barrier may also make Somali students’ parents less willing to attend school meeting and engage the staff concerning their children’s performance. These researchers opine that to worsen this situation, most UK schools do not have specifically tailored arrangements to reach out to such parents.

Dig deeper into Historical and Modern Perspectives on Nepalese Women with our selection of articles.

Furthermore, Gillman (2017) highlights the issue of lack of or insufficient parental support. These authors claim that most parents of the Somali heritage students do not help the students since they cannot speak English and do not have prior education. Therefore, besides not understanding how the education system works or its specific importance, they can also not communicate fluently in English hence offer little or no support to their children undergoing education in UK school (Gillman, 2017).

Continue your exploration of Somali English Bilingual Analytical with our related content.

According to Rutter (2004), the other reason behind the low academic attainment among Somali students in UK schools is families with single parents. This researcher suggests that about 20% to 70% of families of Somalis have women as their family heads. The researcher associates this male absence with the possibility of them being killed back at home or splitting up because of their work in Gulf countries or because of divorce. The lack of both parents in the UK means that the single parent struggles alone to maintain the family leading to economic deprivation and the challenges associated with it like low income, lack of sufficient and high-quality housing, food, clothing. Rutter (2004) suggests that these effects could cause low academic attainment among these students because they lead to stress and anxiety in the students, reducing their focus on school work.

Other reasons associated with low academic attainment among Somali students in UK schools include living in overcrowded neighbourhoods (Ismail, 2019). These authors claim that you may find one family with six children living in a tiny space and noisy environment where a child or student can neither have room to store learning materials or study. Additionally, these individuals often experience racism, meeting culturally biased teachers and living in communities where they are seen as less human beings (Ismail, 2019). Together with trauma because of the civil war back home, these factors may make it difficult for the students to settle in and instead manifest behaviour such as irritability, aggression, depression, withdrawal, and lack of morale or motivation (Ismail, 2019). Moreover, Ismail (2019) claim that these students may show poor attendance at schools and in addition to the poverty and stressful dwelling places; these individuals are on track towards poor academic performance.

Analysis of the research approach and findings

The online questionnaires and zoom focus groups highlighted some of the key challenges Somalis students experience in UK schools and the reasons they came into the country in the first place. First, quantitative data show that of the individuals who took part in the study, none was born in the UK in filling the questionnaire. One of the participants came into the UK when she was between zero and five years. Another young woman came into the UK when she was between five and ten years old. Additionally, one came to the UK when she was between thirteen and fifteen years old, while two came to the UK when they were above fifteen years old. Of all the individuals who took part in filling the online questionnaire, the reasons for coming into the United Kingdom were pursuing business opportunities. In contrast, others said that it was a family decision to leave their home country for different reasons. Others said that they came into the UK to come and live with their family members already settled in the United Kingdom. The participants stated that they started school in the UK when their English level was intermediate, poor or very poor, with only one saying that she had intermediate English fluency. None of the participants could speak English Fluently, showing how the language barrier was a problem to their settling in. Most participants stated that the language barrier was their biggest problem with others, stating that the lack of a role model and the absence of a support system and racism were a concern, preventing their academic attainment from improving. In general, these participants stated that the availability of influencers and understanding the UK education system and extra support to Somali students would help them improve their performance. Additionally, the results attained from the questionnaire analysis indicate that most of the parents had limited language ability, making it difficult for them to offer any help to their children’s learning and education. These results are in tandem with the literature above that indicates language barrier, lack of support, racism and other factors hindering better academic attainment among students of Somali heritage.

To validate my questionnaire and findings, I asked my university supervisor to critique to help determine whether the questions were appropriate to my research topic. Corrections were made to fine-tune the questions and direct them to a specific audience, young Somali women studying in the UK. Using the Microsoft forms, I created an online questionnaire that could be answered by willing participants, making it easy to collect data on the topic during the coronavirus pandemic. This tool was appropriate for this study because I could easily get the answered questionnaires at home through the online platform. By receiving answered questionnaires, I engaged with the specific issues that I felt were of greatest priority, particularly on the barriers such as racism, language and lack of support and programs to improve Somali students’ performance. The combination of open-ended and closed questions allowed participants to answer questions fully and express how the various barriers limited their attainment. The online questionnaire and zoom focus groups were both engaging and interesting, giving me the chance to collect satisfactory answers to my research questions. The zoom focus groups made it possible to include participants from cohort students and allowed me to collect information. This further highlighted the challenges that students of Somali heritage and their parents experience in the UK regarding academic performance. For instance, the issue of the wider-society racism.

The inability to conduct face to face focus group due to the pandemic made it quite challenging to discuss the issues further. It was, therefore, problematic to collect adequate information based on seeing the participants’ expressions and understanding their feelings in terms of how these issues affect their academic attainment. The qualitative analysis made it possible to assess the social aspect of the participants’ life, making it easier to understand how the various issues affect them. On the other hand, the quantitative approach made it possible to quantify the number of Somali students affected by social, psychological and economic issues. Through this study, my quantitative and qualitative research knowledge had increased compared to when I proposed the project. However, I could not foresee the pandemic, which changed my approach from face-to-face focus group to online zoom. I am glad that even though the pandemic limited my ability to conduct face to face focus group, I was still able to maintain ethics in my online zoom by receiving the participants’ consent and the university’s permission before starting the study.

Ethical Approach

Despite the fact that the research was to be conducted through conventional methods involving face to face data collection techniques, I still considered it ethical to continue with the research through an online platform. Even though the study faced a limitation of respondents, the online questionnaire administered and the zoom meetings helped the research grasp what I would have found in the field.

Ethical considerations was imperative in this research as it served to support the valuable requirements for collaboration during the work period. Given that this research depended on the collaboration between the researcher and young Somali women participants, the researcher ought to offer assurance to protect the interest of the target groups like their keeping the participants’ identities hidden and safely keeping the collected data from unwanted parties. Even though this study was challenging to continue with because of the COVID-19 pandemic, I still continued with it, keeping in mind all the necessary ethical considerations. This was possible given the fact that data collection was to be conducted through an online process.

Among the key aspect that I considered in the process of research was objectivity. It is worth noting that the study was conducted during the pandemic stricken season, thereby justifying the need for objectivity. The aspect of objectivity was important since it guided me to avoid the issue of personalizing the values in the process of data collection and analysis. Furthermore, the aspect came in handy in ensuring that the research does not alter the research finding to suit personal beliefs, perspectives or expectations.

Another issue of gravity in research is the consent of respondents. In the instant study, the researcher ensured informed consent of the participants to ensure that they voluntarily take part in the study. Important elements of the study were well elaborated to the respondents to understand what they were taking part in. By doing so, the study participants had an opportunity to choose whether they participated in the study and under which circumstances. Additionally, informed consent ensured that the participants understood how to respond to various questions. However, given that the study was conducted online, I was forced to do so through email to adhere to COVID-19 guidelines. Apart from that, I ensured that the participants were given the final report of the study findings to understand and raise concern before the report is finalized for publishing. Given the sensitivity of the research, I needed to assure the respondents of the confidentiality of their responses. This ensured that the privacy of any individual participating in the study is well upheld, providing an environment where rapport and trust were built with the participants. Therefore in the instant study, the identities of the participants were concealed as exposing them. In this context, I also assured the participants that the information received will be well safeguarded to serve the intended aim.

As researcher and being a young Somali woman with some past unpleasant experiences, I knew that this study was likely to cause me and my fellow young women participating in this research to recall unpleasant or emotionally upsetting experiences. Therefore, I had to ensure that everybody taking part in the study consented and that there was necessary support such as family support to calm them down in situations where they became sad, emotional, anxious or depressed because of the bad memories. The support I had during this study was very useful because my family and friends provided the necessary environment for me to overcome the bad and sad memories. As a result, I have been able to work through some of these issues while developing the research project and through discussions with my supervisor. The available support made me feel able to manage and successfully complete the topic safely.

Furthermore, to consider the aspect of “carefulness” during the study. In this case, as researcher myself I ensured that I carefully reviews the data collection instruments to eradicate issues that would otherwise prove sensitive and vice. Apart from this, it was also my responsibility to ensure that careless mistakes are avoided during the research process. The presentation of results was carefully and critically assessed to ensure that I present the final findings worth the purpose of the study. I also considered the aspect of emotional balance during the study. Some of the issues raised in the study would remind the participants of the experience and traumas.

The process of acquiring ethical approval seemed slightly different from what has always been given because now, I had to factor in the problem of the Covid-19 sensitivity (Vindrola-Padros et al., 2020). The process included key elements like where proving whether I need ethical approval or not; the number of applications that I had to make; where the applications were to be made, and the key ethics the application should have. The challenge experienced during the application process was the delay of approvals due to the change in operations due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the issues related to isolation and lack of movement, as well as keeping social distance, making it difficult to reach participants of the study (Vindrola-Padros et al., 2020). In my view, the only issue that has changed in the aspect of ethics during this pandemic season is the additional Covid-19 safety consideration ethic which implies that the researcher should ensure the health precautions of the respondents. However, through the online questionnaire sharing aspect, the issue was well taken care of, helping me avoid explicit conduct with the participants.

Evidence-based Practice

The literature reviewed in this study has widened my understanding of what Somali girls go through in their endeavors of academic achievement. For instance, the literature in this study has demonstrated how girls with Somali heritage suffer from language barriers. Basing on this fact, the knowledge that has been revealed from the analysis of literature does not only apply to education but can be useful also in others that still involves such migrants who may not be able to read, write and communicate effectively as required in a foreign region like the UK. To address this problem, the literature has revealed that various interventions ought to be put in place collaboratively to meet the need on the ground. As a pertinent issue, the language barrier has stopped many achievements, just as demonstrated by the findings in this study, which only focused on academic achievement.

Another critical issue that I have realized from the literature review based on the sensitivity of the topic in context is that administration of the day plays a big role in determining the fate of a matter. If the government action were to be taken, such issues of low academic underachievement from the foreigner who suffer as a result of their nationality would not be the case. I would advocate for such measures as improving diplomatic relationship as it is through such channels that the grievances of the sufferers can be addressed. Factually, research has already proved that there is a problem that requires the attention of the main stakeholders, the governments of both nations. However, reluctance in implementing strategies and policies that would help do so is seriously wreaking havoc on the individual efforts undergoing the problems at stake.

In my initial discussion at my workplace, I had come across some anecdotal information that the study has proved right. For instance, my colleagues had touched on several occasions about racism, low living standards, and discrimination, among others in foreign countries. This study, through its findings and the reviewed literature, has demonstrated that the anti-racism campaigns that have been ongoing at the workplace, schools, places of worship, shopping malls, among other areas, should continue. Still, with a different approach, maybe that would prove ideal in this period we are living in (Joseph-Salisbury, 2020)

Based on my project's objectivity, I have different expectations that needed to be proven through research. One of the critical issues was actually to prove scientifically that the issues that are being spoken about daily on the streets, churches, places of worship, workplace, and even schools on barriers of Somali girl academic achievement are real. Furthermore, I desired to document evidence that various stakeholders can reference in addressing the issues associated with the topic in context. It is also important to mention that the respondents require a voice of representation; therefore, another expectation during this study was that I would help those students who are undergoing this problem speak on behalf of those who cannot be reached. Finally, the fact that research is one of the forces of enriching the knowledge motivated me to endeavor this study, hoping that the results will reflect the true picture, hence the area's knowledge in context.

Conclusion

The issues articulated in this study are of great intensity that considerations should be made with a solution-based approach. Amongst the issues that the study established is that there are several barriers that the study established concerning the state of Somali school going students and academic achievement. As demonstrated in the literature review and the study findings, one of the leading barriers is a language difference.

The language barrier has caused wreaked great havoc on academic achievement, given that understanding of the language used, mainly English, takes time. It should be well noted that the people of Somali descent use the Somali language as their main language. Additionally, most of the work and assignments should be read in English, the UK's official language. Understanding teachers and curriculum would therefore prove to be a major impediment in the course of their studies.

It is also worth noting that there is a direct correlation between academic achievement and the economic status of an individual. One of the main factors that came out during the study is that some girls of Somali descent do come from economically deprived families. Therefore, access to good education facilities has proven a barrier in their efforts of academic achievement. The idea of separation by economic class implies that good schools and educational facilities belong to the economically elite families leaving the ordinary schools to lower class people where some Somali girls fall. Additionally, low economic status implies the kind of lifestyle a student would live, which leads to a life full of stress and anxiety hence low academic achievement.

The stereotyping mentality has also served as a great challenge. Somali girls are seen to be of African descent, disadvantaging them as they are seen as second class citizens. The treatment from such incidences always leaves affected students traumatized and discriminated resulting in low academic achievement. In the same line, the aspect of workforce diversity has not been tackled well in the UK, given that there are very few black teachers who, in the real sense, would understand the dynamics that affect an African child in such circumstances.

As this research comes to an end, I can say I have raised an important issue that needs to be tackled by the Government, schools and the community, the issue of young Somali women students and students from ethnic minority groups in the UK in general experience social related challenges hindering their academic attainment. As a young Somali woman, I have come to the conclusion that what my fellow minority students in the UK need are just the correct support and a system that is put in place for them. In the future I will be an advocate for the voiceless. I believe my research will raise awareness so that these issues will be solved in the near future. I have great hope that young Somali women will have a bright future ahead of them.

Recommendations

The top priority should be addressing the language barrier in schools. This can be attained by creating an intensive program geared towards attaining a certain level of fluency in English at a basic level before the transition to the next level of intermediate classes occurs.

In the same vein, parents should be encouraged to take full responsibility for supporting their children, especially the young women.

Campaigns on stereotyping, racism, discrimination, among other factors, should be encouraged and, if possible, upgrade the instruments of advocacy.

References

Alitolppa‐Niitamo, A., 2004. Somali youth in the context of schooling in metropolitan Helsinki: A framework for assessing variability in educational performance. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 30(1), pp.81-106.

Bigelow, M., 2011. (Con) texts for cultural and linguistic hybridity among Somali diaspora youth. The New Educator, 7(1), pp.27-43

Demie, F. Lewis, K, McLean, C., 2006. The Achievement of African Heritage Pupils: Good Practice in Lambeth Schools. Lambeth Research and Statistics Unit

Gillman, P., 2017. The achievement of Somali boys: a case-study in an inner-London comprehensive school (Doctoral dissertation, University of Oxford).

Harris, H., 2004. The Somali community in the UK-What we know and how we know it ICAR. Kings College London.

Hammond, L., 2013. Somali transnational activism and integration in the UK: Mutually supporting strategies. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 39(6), pp.1001-1017.

Ismail, A.A., 2019. Immigrant children, educational performance and public policy: a capability approach. Journal of international migration and integration, 20(3), pp. 717-734.

Joseph-Salisbury, R., 2020. Race and racism in English secondary schools. Runnymede Perspectives.

Rutter, J., 2004. Refugee Communities in the UK: Somali Children’s Educational Progress and Life Experiences. London Metropolitan University.

Vindrola-Padros, C., Chisnall, G., Cooper, S., Dowrick, A., Djellouli, N., Symmons, S.M., Martin, S., Singleton, G., Vanderslott, S., Vera, N. and Johnson, G.A., 2020. Carrying out rapid qualitative research during a pandemic: emerging lessons from COVID-19. Qualitative health research, 30(14), pp.2192-2204.

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts