Understanding Fractions in Mathematics

Introduction

Fraction is one of the topics, which is conceptually challenging and most in need of attention pointed out by Behr et al. (1984). Alon (2012) sees fraction as building blocks in the context of ratio and proportion as well as studying decimals and percentages. Furthermore, good understanding of fractions leads to success in algebra suggested by the National Mathematics Advisory Panel (2008). Brown and Quinn (2007) also endorsed the view whereas Booth and Newton (2012) asserted that competence in algebra is essential to higher levels of learning in mathematics.

Department for Education (2013) has led the path of progression, shown below and also confirms the sequence of thought, which runs through the above arguments about the vitality of acquiring conceptual understanding in fractions:

This study is going to identify and critically examine to engage with current debates concerning the teaching and learning of fractions. The critical analysis will be comprised of firstly, considering the common misconceptions that the learners experience in learning fractions and then secondly, to review the existing teaching and learning approaches to determine the best resolution, which will ensure all the learners, who are able to understand the concept and make progress within the topic of fractions.

Common Misconceptions with Fractions

Fractions often cause challenge due to their interpretation to represent and describe things e.g. sometimes fraction is narrated as a part of a whole (quarter of a pizza) or part of a set (quarter of the class). Sometimes it is numerically represented i.e. a position on a number line. Dickson, Brown and Gibson (1984) described in detail the relative conceptual challenge of these different ‘interpretations’. The above progression table presented in introduction reflects the different levels of complexity of these interpretations. Two aspects of these distinct interpretations that present the conceptual challenge are:

a part of a whole - when an object is ‘divided’ or ‘split’ into two or more equal parts

a position on a number line – numbers which are represented between whole numbers;

Passing through the journey of interpretations in Key Stage 1 and 2, potential difficulty may arise in Key Stage 3 when the children are asked to exhibit the leaned knowledge to solve problems. Children find it difficult to apply the learned knowledge of fractions through these interpretations to problem solving situations because they don’t know which interpretation is to apply (Nickson, 2000). These findings imply that children need to have clearer, deeper and stronger conceptual understanding of fractions in order to bridge the gap between Key Stage 3 and Key Stage 4. Furthermore, a clearer understanding of the concept and selection of interpretations to solve particular problem is required to deliver the content well and fill the gaps. This should be addressed in teaching.

Further analysis of these common misconceptions associated with different interpretations of fractions is now discussed in detail.

Part of a Whole

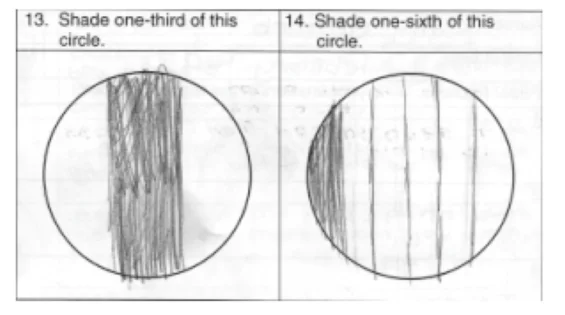

Gould et al. (2006) explains that a number of students have misconceptions with the concept of fractions as part of a whole. The exercise of giving questions on shading areas where the shape is already partitioned based on the assumption of level of understanding that may not be in place. This is shown in figure 1, when the students were asked to make their own partitions to shade the certain fractions, the misconception has emerged as the pupils did not realise that partitions have to be equal and incorrectly partitioned the circles.

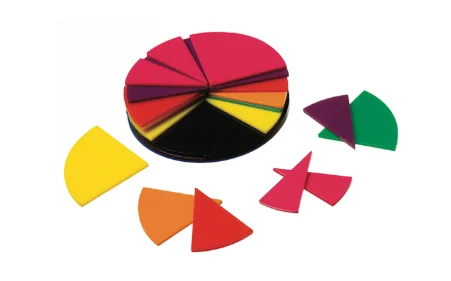

Alon (2012) recommended the use of ‘manipulatives’ to help learners being able to divide/partition circles such as sectors of a circle and these models aid pupils to comprehend the conceptual understanding of fractions. This is a good visual representation of the part-to-whole relationship, however its scope is limited as a conceptual aid due to not being able to use in isolation, as the learners need to be exposed to the other interpretations of fractions too.

Position on a Number Line

According to Wu (2001), number lines are not always used to represent the fractions; hence the relationship between the whole number and fractions is not always obvious. In a visual representation of the number line, the learners become used to counting whole/discrete numbers and hence find it difficult to fit the fraction on number lines (Gallistel and Gelman, 1992). Tzur (2004) claimed that, prior knowledge on whole numbers is key here which interferes as well as helps; when students identify their errors understand and incorporate their new ideas. However, there is a contrast between the arguments of Hunting and colleagues (1996) who claimed that after learning fractions, students’ knowledge of natural numbers was stronger whereas Mack (1995) thought that, once children learnt about fractions, they get confused and incorrectly apply the concept to the whole numbers. An ‘Integrated theory of numerical development’ is presented as a suggestion by Siegler et al. (2013), where the understanding of number gradually increases as well as filters to the realisation that all the real numbers have magnitudes and can be positioned at specific locations on a number line. During my placement, my mentor set a task to key stage 3 students. The task was to sort a list of the improper fractions into those that were less than 1 and those that were greater than 1. Some students follow the method of comparing the numerator to the denominator – if the numerator is bigger than the denominator then the fractions is bigger than one, if smaller then the fraction was smaller than 1. Whilst this strategy suited to some, others did not understand the logic behind the concept that why this was true and the students who forgot the ‘rule’ could not make any progress. My reflection suggests that, a number line would be a beneficial visual representation to aid and clarify the concept (Discussed in detail under the section of Review of Current Approaches to Teaching and Learning – Multiple Modes of Representation).

Over-Reliance on Procedural Knowledge

Procedural knowledge is defined as the ability to follow a sequential algorithm to solve mathematical problem (Miller and Hudson, 2007). Misquitta (2011) - in the context of fractions- links procedural knowledge to operations and use of algorithm, for example, making the denominators same to add fractions. Byrnes and Wasik (1991) sees this procedural knowledge at early stage of learning as rote learning and argues that concept oriented tasks are easier to comprehend in comparison to those which use procedural knowledge. Furthermore, Mack (1990) and Peck and Jencks (1981) noted in their studies that, even though pupils with procedural knowledge were able to complete the task but had little conceptual understanding of the topic. During some observations with Key Stage 4 groups in regards to understanding of fractions and their equivalences in terms of percentages, and through the conversation with the students, it was evident that mode of teaching was based on rote learning. For example, half is equal to 50% and three quarter is equal to 75%. Although there was little evidence of conceptual understanding in this case, the students’ responses were accurate. According to Hallett et al. (2012), these apparent inconsistencies could be attributed to different learning styles amongst the learners involved in the studies. Some students may have better ability to comprehend theoretical underpinning of fractions, whereas other may have a better ability to retain the procedures. One of my adaptations to the teaching pedagogies based on the suggestion by Misquitta (2011), where I differentiated the task on fractions for year 9, a low ability group of learners with a range of special needs using more explicit instructions and by providing frequent practice of fractional computation. The guidance provided by the literature of Kroesbergen and Van Luit (2003) was used during my lesson to teach in small segments, addressing the needs of pupils based on memory deficit, short attention span and slow pace to task completion. This practice ensured that, the learning was differentiated to suit the needs for all the pupils including the low ability. Hecht and Vagi (2012) noted that, to excel in mathematics both conceptual understanding and procedural knowledge are required. Furthermore, the term ‘iterative process’ has been used by Rittle-Johnson et al. (2001), to describe the acquisition of conceptual and procedural knowledge and propose that, for some learners attaining one type of knowledge lead to improvements in the other. This may be the case that, pupils may need both but in contrast, Behr et al. (1983) are sceptical about the over reliance on procedural knowledge as without a sound understanding of the concept, procedures can be confusing and hard to remember. This could also lead to a significant number of errors in calculations, when solving problems. Gabriel et al.’s (2012) study exposed that, the delivery mode for teaching fractions is mainly based on procedural knowledge. During my placement, I delivered a lesson on how to find fractions of an amount to key stage 4 students using the procedure multiply by the top, and then divide by the bottom. The language of the algorithm was simple and students found it easy to comprehend and apply to simple questions such as ‘¾ of 40’. In contrast to this, the students were unable to take their procedural as well as conceptual understanding to next level when language of the question was changed to ‘what fraction of 45 is 35?’. What I have learned from this experience is that, learning is a ladder and lesson should not be fixed to one procedure rather more open ended tasks with a variety of compare and contrast questions should also accompany to develop better understanding (see Review).

Addressing Misconceptions

A quote from the conversation with my mentor, “Teaching is not something where everything is fixed, you should judge and adapt there and then by responses from the learners to address their needs as well as monitor their progress for the best outcome”. The earlier discussions about the misconceptions as well as feedback from my mentor set the grounds to adapt and adjust my approach to either prevent misconceptions from forming or allow the opportunities for misconceptions to take place and address them as separate learning episode. OFSTED (2012) states, that errors are essential part of learning and effective teachers nurture a climate where learners do not mind making mistakes. This allows pupils to take risks and through that their understanding can be developed if they have opportunity to explain their thinking to their peers. Research endorses the findings of OFSTED. According to Cockburn (1999), mathematical errors provide the opportunity for the teacher to probe into child’s thinking process; an effective mechanism for assessment for learning and, with careful handling can enable the children to learn from mathematical mistakes. Swan (2001) focused on to that by suggesting that, misconceptions are in fact essential stages in children’s mathematical development. In contrast, Koshy (2000) stated that, the children have expressed strong feeling of anger, frustration, disappointment and demotivated on making mathematical mistakes, which is a potential barrier to learning. Gottfried (1982) further argued that, improved level of achievement is down to competence in the subject that comes through the motivation. This suggests that, a careful consideration should be given to prevent harmful effects to self-esteem by providing the learners the opportunities to independently review their own misconceptions and correct them accordingly. Creating situations, where the children feel more in control of pointing out their mathematical errors, lead to widen the opportunity for them to explore and discuss their own misconceptions (Spooner, 2002). During a key stage 3 lesson on equivalent fractions, I set a plenary task which was done in pairs where students were to discuss with each other and complete the task. Student’s conversations with each other allowed me to identify if there were any gaps or misconceptions still there and they were addressed through intervention and were asked to reflect back on what they have learned and clarify their misconceptions.

Review of Current Approaches to Teaching and Learning

Developing Conceptual Understanding

The study by Gould et al. (2006) revealed much evidence of student misconceptions with fractions (figure 1). Some recommendations were made for suggesting about how best promote conceptual understanding with fractions. According to Gould et al. (2006), first recommendation is to let the pupils partition their own shapes, so that teacher can draw upon whether students have conceptual understanding of the fractions. Planning key stage 3 lessons on fractions, following the recommendation, for my first lesson on finding the fraction of an amount I asked the students to partition circles into different fractions. Model of fraction circles was provided for support (figure 2). A model of fraction was also used to support the students, who needed more help through visual representation of fractions (figure 3) to address differentiation.

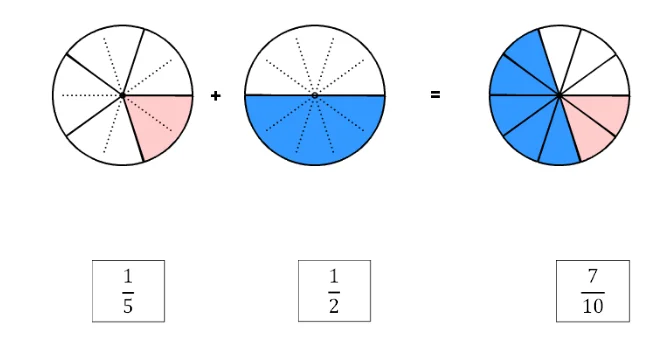

In the main task, the students were required to partition circles into fractions independently without any support, hence allowing them to draw as per their levels of understanding of finding fractions of amounts. The model of fraction circles and fraction cake has been provided to the students with a very useful visual representation of part-whole relationship of fractions especially for those who needed extra support. The misconceptions that have been presented at the beginning of the lesson were successfully addressed and checked through the plenary activity at the end. The first exquisite lesson using visual aids led the pupils to make further progress in a series of lessons on fractions. The students were given an opportunity in the last lesson to practise addition and subtraction with fractions. Instead of using procedural method finding a common denominator using lowest common multiple method, pupils were encouraged to use fractions circles (figure 4) to identify lowest common multiple. This visual tool helped pupils to actually understand what it meant to add or subtract fractional amounts and apply the learned concept to partition their own shapes to complete the task. Fraction circles even refined the concept of equivalent fractions as well as part-whole interpretation to be able to add and subtract fractions.

Use of ‘compare and contrast’ questions is the second recommendation, made by Gould et al. (2006) to draw student’s misconceptions and allow for open-ended discussion. In order to exercise this strategy, I expose the following question to a Key Stage 4 group of learners: ‘how is a third of a circle like a quarter of a circle? What is the difference?’ The relative size of fractions was emerged as discussion point through these open-ended questions. This opportunity allowed me to address the misconception that a third is smaller than a quarter. Watson and Mason (1998) emphasized on creating classroom climate, which is open to discussions and questioning, as it helps to elicit misconception that might not have appeared though student’s responses to learning activities (see Common Misconceptions with Fractions – Addressing Misconceptions).

Multiple Modes of Representation

Exposure to multiple modes of presentation to support conceptual understanding has significant importance demonstrated by the research in recent years for example Ainsworth (2006), Amato (2008) and Gagatsis and Elia (2004). Multiple representations allow different perspectives, hence scaffold deeper understanding and provide differentiation at the same time to address different learning preferences stated by Ainsworth, Bibby and Wood (1997). While, using fractions circles in my key stage 3 lessons to develop part-whole relationship, I have gathered that, another strategy is required to demonstrate that the fraction can also be positioned on a number line, which is also a harder bit to understand for some pupils. Counting stick was used to aid addition of fractions. An extension activity was set, where the students were asked to identify a fraction on counting stick. For example, locate one half and add three quarters to it. This practice did not only show the part-whole relationship but also the occupancy of numbers on the number line. This strategy was an addition on their exiting knowledge of fraction circles and refined their ability to add fraction by using number line.

The abstract mathematical thinking could be developed through multiple representations especially to those pupils who are only exposed to concrete representations of mathematical concepts. This way variety of multiple representations solidifies the strengths and cancels out the weakness of having just one representation in place (Elia, Gagatsis and Demetriou, 2007). A study by Isiksal and Cakiroglu (2011) has also revealed in their findings that prospective teachers also agreed to the use of multiple representations to deliver fractions as they deepen students’ conceptual understanding. The study has also mentioned the use of manipulatives and other instructional materials to make fractions more understandable for the students. To exercise the multiple mode strategy while teaching equivalent fractions to key stage 4 students, I used two different representations. First one was shading grids (figure 6). This elicited on the students’ comprehension of the part-whole relationship of fractions and worked as a beneficial visual tool to partition the shapes. This is a good follow on from portioning circles into fractions and it could be adjusted in a scheme of work that includes both the activities placed along the path of progression within the topic.

The visual aid used for the second representation was a fraction wall (figure 7). Although this was not utilised as a means to convey part-whole relationship, and the idea behind the strategy was to engage the pupils through an accessible game in order to introduce a fraction wall for progressing onto further details of fractions. Two key benefits of this approach achieved were; the students being able to find equivalent fractions and also could compare the relative magnitudes of fractions more easily. Students also found that, the fraction wall helped those arranging fractions in order of size. Cuisenaire rods are more tactile resource to address students’ needs too which I will consider to use too in future.

Real-Life Contexts

Students find the fractions hard to understand because they do not why they need to use them. Skemp (1986) used a term ‘A need for new numbers’ to introduce fractions and suggested that, we need fractions when we are using measures (p.173). For example, if the length of an object is measured in centimetres, it may be that, the length lies between two unit measures. In order to measure that difference between two units, we need to introduce a fractional unit, which is also a solid example from real-life application in the context. Lesson focus can determine which tools to use, for example a tape measure could be used to measure the length of an object, and a measuring jug could be utilised for measuring the capacity of a liquid, weighing scales for measuring a mass.

The rationale behind learning ‘new numbers’ as fractions is necessary to be explained to the children by helping them to understand, the importance of fractions. Lamon (in Couco) states that ‘…traditional instruction in fractions does not encourage meaningful performance…’ (p.146). Children were able to solve more complex fractions where learning was underpinned by understanding shown in findings by her research. Furthermore, Critchley (2002) states that problem solving activity based on real life example involving the use of fractions, supports child’s ability as well as understanding. I delivered a lesson on fractions to Key Stage 3 mixed ability group of learners. The students were to cook and share pizza amongst their class fellows. The lesson was differentiated in a way that, less able students were to find simple fractions of amounts, so that pizza could be shared using halves, quarters and eights. A further challenge was added by placing questions like three students each want 3/5 of a pizza, will two whole pizzas suffice for them? The rationale behind the challenge was to bring addition of fractions into the context too. The middle ability students were to follow the recipe by using measuring jug and weighing scales to measure the ingredients, whereas the higher ability were given the task to make pizza enough for three people by utilising their own justified judgment and even adapting the recipe to make pizzas enough for the whole class (16 in total). This way, the students were also given an exposure to the concepts of ratio, proportion and scale factors.

Relevance of the topic to real life context made it quite enjoyable experience for the learners. I inferred from this experience that, practical work along with the support of images provided; the students could actually contextualise mathematical concepts and experiences as well as they were able to abstract the underpinning mathematics. This transition from the written exercises of fractions to cooking pizzas was not smooth for all the pupils. Some students struggled to comprehend the formal mathematics and the abstract concept from their practical work. For example, one of the learners could not grasp the equivalence of two eighths and quarter a slice of pizza. This might be due to not having enough practice on equivalent fractions. However, overall for the majority of the learners, the experience was very useful and it enabled them to conceptually understand the fractions and to make progress.

Conclusion

Awareness of the different interpretations of fractions is prerequisite for a good practice in teaching and learning of fractions as well as to provide the opportunities to address common pupils’ misconceptions in the lesson. There are some benefits of procedural knowledge in terms of differentiating for less able learners, but the scope of procedural knowledge is limited in its usefulness, as the children require the development of conceptual understanding. Strategies aimed to develop pupils understanding by creating their own fractions e.g. partitioning their own shapes, open-ended questioning using compare and contrast strategies. Multiple modes of representation should be used by the teachers to communicate different interpretations of fractions including investigation based problem-solving activities. Real-life examples along with some practical work are useful but carefully chosen, followed by effective dialogue with the students to establish the extent of their understanding. Students’ correct answers on a concrete task should not be used as a validation of conceptual understanding the abstract. Both practical and abstract work need to be explored in their own right about the perceived links between the two.

References

Ainsworth, S. (2006) ‘A conceptual framework for considering learning with multiple representations’. Learning and Instruction, 16, pp. 183 – 198

Ainsworth. S. Bibby, P., and Wood, D.J. (1997) Evaluating principles for multi-representational learning environments. Paper presented at the seventh European Association for Research on Learning and Instruction, Athens, Greece

Amato, S.A. (2008) ‘The use of relational games in initial teacher education: Bringing the classroom into the lecture theatre. In B. Clarke, B. Greyholm and R. Millman (Eds.), Tasks in primary mathematics teacher education: Purpose, use and exemplars (pp. 177-196). New York: Springer

Alon, S. (2012) ‘Building a more complete understanding of fractions: Evidence and Analysis of a classroom case study’. National Teacher Education Journal, 5(2), p115-127

Behr, M. J., Wachsmuth, I., Post, T. R., & Lesh, R. (1984) ‘Order and equivalence of rational numbers: A clinical teaching experiment’. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 15(5), pp. 323–341

Behr, M., Lesh, R., Post, T., Silver, E. (1983). Rational number concepts. In R. Lesh & M. Landau (Eds.), Acquisition of mathematical concepts and processes (pp. 91–125). New York: Academic Press

Bezuk, N., Cramer, K. (1989) Teaching about fractions: What, when and how? In P. Trafton (Ed.), New directions for elementary school mathematics: 1989 Yearbook (pp. 156–167). Reston: National Council of Teachers of Mathematics

Booth, J. L., Newton, K. J. (2012) ‘Fractions: Could they really be the gatekeeper’s doorman?’. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 37, pp. 247-253

Brown, G., Quinn, R. J. (2007) ‘Investigating the relationship between fraction proficiency and success in algebra’. Australian Mathematics Teacher 63 (4), pp. 8-15

Byrnes, J.P., Wasik, B.A. (1991) ‘Role of conceptual knowledge in mathematical and procedural Learning’. Developmental Psychology, 27, 777–786

Couco, A. (2001) The roles of representation in school mathematics. NCTM Yearbook for 2001.

Dickson, L., Brown, M. and Gibson, O. (1984) Children Learning Mathematics: A Teacher’s Guide to Recent Research. London: Cassell Education

Elia, I., Gagatsis, A., and Demetriou, A. (2007). The effects of different modes of representation on the solution of one-step additive problems. Learning and Instruction, 17, pp. 658 – 672.

Gabriel, F., Coche, F., Szucs, D., Carette, V., Rey, B., Content, A. (2012) ‘Developing Children’s Understanding of Fractions: An Intervention Study’. Mind, Brain and Education, 6(3), pp. 137-146

Gagatsis, A., and Elia, I. (2004). The effects of different modes of representation on mathematical problem solving. In M. J. Hoines and A. B Fuglestad (Eds.), The 28th conference of the International Group for the Psychology of Mathematics Education: Vol.2. pp. 447 – 454). Bergen: Bergen University

Gottfried, A. (1982) ‘Relationships between academic intrinsic motivation and anxiety in children and young adolescents’. Journal of School Psychology, 20, pp. 201–215

Hallett, D., Nunes, T., Bryant, P., Thorpe, C. M. (2012) ‘Individual differences in conceptual and procedural fraction understanding: The role of abilities and school experience’. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 113, pp. 469-486

Hecht, S. A., Vagi, K. J. (2012) ‘Patterns of Strengths and Weaknesses in Children’s Knowledge about Fractions’. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 111(2), pp. 212-119

Isiksal, M., Cakiroglu, E. (2011) ‘The nature of prospective mathematics teachers’ pedagogical content knowledge: the case of multiplication of fractions’. J Math Teacher Education, 14, pp. 213-230

Mack, N. (1995) ‘Confounding whole-number and fraction concepts when building on informal knowledge’. Journal for Research Mathematics Education, 26, pp. 422–441.

Miller, S. P., Hudson, P. J. (2007) ‘Using evidence-based practices to build mathematics competence related to conceptual, procedural, and declarative knowledge’. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 22(1), pp. 47–57

Noss, R. and Hoyles, C. (1996) Windows on Mathematical Meanings: Learning Cultures and Computers. Dordrect: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Rittle-Johnson, B., Siegler, R. S., Alibali, M. W. (2001) ‘Developing conceptual understanding and procedural skill in mathematics: An iterative process’. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93, pp. 346–362

Spooner, M. (2002) Errors and Misconceptions in Maths at Key Stage 2: Working Towards Successful SATS. London: David Fulton Publishers

Tzur, R. (2004) ‘Teacher and students’ joint production of a reversible fraction conception’ Journal of Mathematical Behavior, 23, pp. 93–114

Wu, H. (2009) ‘What’s sophisticated about elementary mathematics?’ American Educator, 33(3), pp. 4–14

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts