How should multi-national companies

- 55 Pages

- Published On: 04-12-2023

Research background

My research question is How should multi-national companies (MNCs) improve cross-cultural expatriate leadership to help the MNCs be more profitable in the future? The reason why I want to research this topic is because expatriates have become increasingly important due to the rapid growth of overseas investment, expatriates are frequently sent by their Multinational companies to live and work for a year or more abroad in a branch of multinational enterprise (Kraimer et al. 2016; Banerjee et al, 2012). In May 2008, a GMAC Relocation Trends survey discovered that there are 68% of Multinational companies continually relocating expatriate employees overseas (Deresky, 2011). According to the statistics, there are over 80% of MNCs that have already successfully sent expatriates across the globe, and the number of expatriates continually increase every year (Black and Gregersen, 1999). For those seeking business dissertation help, understanding these dynamics is crucial.

However, failed expatriate assignments occupied a high percentage within the companies (Tahir, 2018), which can have a wide-range negative impacts on both the companies and the employees. In terms of impacts on the companies, there are both direct and indirect costs to consider: Direct Costs of expatriate failure contain primarily to the relocation costs of both the employees and their families, including airfares and shipping costs. A failed expatriate assignment can cost company from USD 250,000 to 1,000,000 (Peng, 2018). Indirect costs primarily include loss of productivity both in terms of underperformance whilst on overseas assignments and the days occupied with relocating. Much often, indirect costs associated with expatriate failure often exceed estimated direct costs (Ashamalla and Crocitto, 1997; Harvey, 1985). In terms of impacts on the employees, failed assignments can be damaging to the employee’s physical and mental well-being due to low self-esteem, loss of prestige and respect among colleagues, weakening of the psychological contract, family issues, damage to an employee’s career path including reduction of promotion opportunities (Cuzzo et al. 1994; Shaffer et al. 2006; Varner and Palmer, 2002). Expatriate failure generally is defined as “a premature return”. This could mean not finishing overseas assignments before the contract is completed. Alternatively, it could refer to problems adjusting to foreign working environments and poor performance like high absence (Forster, 1997).

Expatriates play a role as an agent in the overseas assignments, to deliver the knowledge from headquarters to subsidiaries or from subsidiaries to headquarters (Musasizi et al. 2016). There are certain management and leadership skills required for the expatriates, such as a good knowledge of the parent’s country culture, workforce environment, business trend and parent’s country government policies, due to the challenges they will be facing during their overseas assignments. In reality, the majority of MNCs have encountered high-failure rates of the expatriate foreign assignments caused by the unsuitable management strategies and inappropriate leadership styles. For example, ethnocentric management approach causes the conflicts during the introduction of the headquarter policies. Expatriates from the U.S always face difficulties when they apply the decisions made by the US headquarters, because the local staffs prefer to follow their own procedures. Moreover, the local employees are suspicious of the decisions from the US all the time. They believe the same strategies are working in the US but nobody can guarantee they can be effective in other countries. Expatriates have to be assertive and use dynamic leadership style based on different scenarios. To make the situation even more difficult, some local employees feel belittled by following instructions from an “outsider”, which even generate the resentment from local employees toward expatriates. In this case, it is the expatriates’ responsibility to include local staff in the decision-making process, and make sure the local staff are valued and feel they are important for the company.

Expatriates play a role as an agent in the overseas assignments, to deliver the knowledge from headquarters to subsidiaries or from subsidiaries to headquarters (Musasizi et al. 2016). There are certain management and leadership skills required for the expatriates, such as a good knowledge of the parent’s country culture, workforce environment, business trend and parent’s country government policies, due to the challenges they will be facing during their overseas assignments. In reality, the majority of MNCs have encountered high-failure rates of the expatriate foreign assignments caused by the unsuitable management strategies and inappropriate leadership styles. For example, ethnocentric management approach causes the conflicts during the introduction of the headquarter policies. Expatriates from the U.S always face difficulties when they apply the decisions made by the US headquarters, because the local staffs prefer to follow their own procedures. Moreover, the local employees are suspicious of the decisions from the US all the time. They believe the same strategies are working in the US but nobody can guarantee they can be effective in other countries. Expatriates have to be assertive and use dynamic leadership style based on different scenarios. To make the situation even more difficult, some local employees feel belittled by following instructions from an “outsider”, which even generate the resentment from local employees toward expatriates. In this case, it is the expatriates’ responsibility to include local staff in the decision-making process, and make sure the local staff are valued and feel they are important for the company.

It is hard to define leadership due to this complexity and it has been researched in different ways (Muenjohn, 2008; Achua and Lussier, 2000). However, there are still some terms that have been used to describe leadership, such as styles, characters, impact, communication patterns, roles, a job in an authorized position (Yukl, 2006). In fact, leadership can be explained as a process where an influential role has been used by leaders in order to supervise, assist and manage relationships and projects in a team. There is a certain relationship between cultures and leaderships. According to Bae et al. (1993) and Han et al. (1996), cultures make the styles of the leadership different. Expatriate leadership style can be flexible and depends on the circumstances, so there has not been a fixed expatriate leadership style that can be used under any circumstances (Yukl, 2006). In fact, different cultures in the host countries should be the key factor when expatriates apply the relevant leadership style. It is impossible to separate leadership style from the local culture, as it is constantly being influenced by the culture itself (Muenjohn and Armstrong, 2007a). For example, the rating and praise system is different from the US to Japan. American leaders tend to give comments based on individual performance, in comparison to Japanese leaders who prefer to give their comments to the group. This is a perfect reflection of Hofstede culture dimension theory (1984). It is crucial to acknowledge different cultures, as this will enable them to understand the way people conduct business as well as their perspective towards to the world (Hall, 1995). However, misconceptions towards business failures may occur as a result from different people’s beliefs, cultural backgrounds and idealism (Bass, 1990). On the contrary, if the mutual understanding has reached, culture differences can create innovative ideas, thus generate competitive benefit. In order to be successful in the competitive international market, expatriates must adjust their leadership style according to the culture awareness, sufficient information about the host country and sensitivity. Take a deeper dive into Educational Leadership Reflection with our additional resources.

Aims and objectives

Despite the high risk of failure and the large amount of consumptions caused by the failure, 68% of MNCs insist relocating their expatiate employees overseas according to GMAC Relocation Trends survey (Deresky, 2011). What motivate the assigned expatriates who work in subsidiaries of their home country organizations overseas is both their career development and company’s development (Bolino, 2007; Edström and Galbraith, 1977; Stahl et al, 2002). Research indicates that expatriates are able to get faster promotion than non-expatriates (Doherty and Dickmann, 2012). Once the expatriates successfully finished their overseas tasks and returned to the home country, the improved competencies they brought back to the host country are invaluable, the competencies include expatriate experiences, skills, and cultural intelligence. The home country companies will gain further financial benefits from them, meanwhile increase future expatriation successful rate. As for expatriates themselves, they gain opportunities of further experiences, career promotions and financial benefits. Therefore, a successful expatriate overseas assignment is particularly valuable for multinational companies. Moreover, the financial costs for the companies and the psychological damage to the expatriates once the assignments have failed are enormous. In addition, enabling expatriates to face less stress and to have a relative contented life overseas is crucial for expatriates to perform their overseas duties. All these aspects highlight my motivation to do the research with the aim of unveiling ways to make expatriates successful. Examine the certain connections between host country cultures and expatriate leadership styles, then investigate the suitable leadership styles and develop effective leadership strategies for expatriates, in order to help them to overcome word-related difficulties, and to assist them to perform their overseas duties is what my research determined to achieve.

Research questions designed for the questionnaires/interviews

What motivates a person to self-identify as an expatriate leader? What expatriate leadership styles are required in the overseas work environment? What expatriates leadership competencies/qualities/skills are needed when leading a multinational team? How can culture impact leadership styles? What adjustments are required for a domestic leader transferring into an expatriate leader?

Methodology

The aim of the research study is to develop new knowledge and to initiate new perspectives of thinking as well as reflecting on issues by using primary data (Ochsner et al, 2012). This section will analysis research methodologies, approaches, strategies, and techniques, which are applied for conducting the research.

Research design

Kothari (2004) points out that the application of science in the various processes and activities concerned with research methodology, Remenyi et al. (2003) highlights that a research design dictates the direction of the actual study, as well as the manner by which the research is conducted. Saunders et al. (2009) further clarifies that a suitable research design needs to be selected based on research questions and objectives, existing knowledge on the subject area to be researched, the amount of resources and time available, and the philosophical leanings of the researcher. The research design reflects the types of strategies that a researcher can adopt for use in a study, some of which include survey, case study, experiment, action research, ethnography, archival research, grounded theory, cross-sectional studies, longitudinal studies and participative enquiry (Collis and Hussey, 2009; Saunders et al. 2009).

According to Saunders et al. (2009) Research Onion Diagram in figure one, the first layer is about research philosophy, including epistemology and ontology. Research philosophy has impact on further date collection and date analysis. The second layer illustrates research approaches, they can be inductive or deductive, which depend on the research purpose, restrictions and individual perspectives. The third layer explains research methods of the date collection. These methods range from survey, grounded theory, archival research, survey, ethnography, action research and experiment. The fourth layer shows the concern of qualitative and quantitative methodologies. There are three methods to select from, they are Mono-method, mixed methods and multi-method. The fifth layer demonstrates the timeframe of the research, which consisted of cross-sectional and longitudinal. Cross-sectional is for a relatively shorter period of research time, while longitudinal is for a relatively longer period of research time. The last layer displays data collection and analysis.

Guided by the above principles, my research will adopt the use of questionnaires and informal interviews. Griffiths (2009) states that the qualitative research design involves detailed exploration, as well as analysis of particular themes and concerns within a topic. He further highlights the importance of using qualitative approaches as they are particularly beneficial to research topics that are complex, novel or under-researched. As this leaves the results open to the possibility of unexpected findings, rather than predicting an expected outcome, which is often the case for quantitative research.

Philosophical paradigm

Based on the provision of the Research Onion Diagram (Saunders et al. 2009) as shown in Figure 1, my research applied a mixed methods research design, influenced by a pragmatist philosophy (Saunders et al, 2009). The approach embraces aspects of the interpretivist philosophy that treats the world as a conglomeration, which consists of social constructions, meanings in human engagements and lived experiences (Daymon and Holloway, 2002; Gomm, 2008). The interpretivist paradigm works in dichotomy with the positivist model, which views the world as an embodiment of clarity, unambiguity, and verifiable reality that can be studied only with total objectivity (Cavana et al. 2001). My research plans to combine the rationalist, empiricist approaches, and to encapsulates concepts, theories, frameworks in explicating different research concerns, including objectives, questions, phenomena, and behaviours (Abend, 2008; Swanson, 2013; Weick, 2014).

Research method

Using multiple allocable methodologies enables the researcher to gain both abundant qualitative and quantitative data. However, sometimes there is only one methodology applied, because the studies are specific, and need to highlight the research outcomes effectively. Qualitative and quantitative data provides researchers with opposing perspectives in a research. Qualitative data is a dynamic and negotiated reality that seeks a human behaviour perspective, while quantitative data is a fixed and measured approach to establish facts concerning perceived social phenomena. Qualitative data collection is achieved through subjective and personal procedures, entailing observation and interviews, while its analysis includes descriptors, to identify and connect patterns and themes. In contrast, quantitative research involves the measuring of phenomena through tools such as surveys to obtain data, which can be analysed for comparisons and inferences to establish statistics.

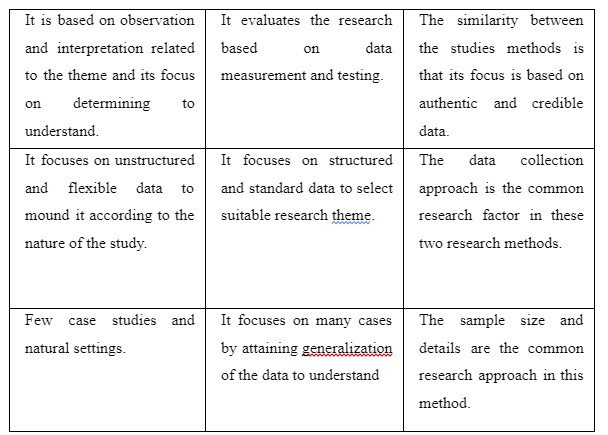

Table one illustrates the characters of qualitative and quantitative research method, and the similarity between them

Data collection methods

Data collection plays an important role in research, its reliability and validity determine the success of the research. My research adopted the mixed method of using both questionnaires and informal interviews. The use of the questionnaires highlights general aspects of expatriates leadership experience in the foreign country. While informal interview further emphasises on expatriates personal perspectives regarding leadership skills.

Data collection methods

Questionnaires

According to Phillips and Stawarski (2008), questionnaires are efficient due to their ability to capture not only an individual’s opinion, but also their attitudes and beliefs. In addition, they are flexible and easy to complete within a short time. The questionnaires will design with detailed questions mostly required Yes/No answer, only in specific limited instances offer ranking scale, also there are few open-ended questions for clarification of deep insight points. In that case, they are easily to complete

Data collection methods

Informal interviews

The use of informal interviews enables researchers to find much deeper and personal insights. It helps to cover the grey areas present in the questionnaires by offering detailed explanations from respondents, as well as ensure credibility and viability of the information provided by them.

Target population

Target population can be defined as a group of people who are of interest to the research process (Goddard and Melville, 2004). These are the people with a specific attachment or closely relevant to the features and subjects of the research (Morse and Richards, 2002). My target population in the initial research process are International expatriates who take International assignments in the UK. The reason they were chosen were for the following: First of all, they have the first-hand leadership experiences in leading the multinational teams. Secondly, they are facing the adjustment issues due to their unique overseas experience.

Continue your journey with our comprehensive guide to How should multi-national companies.

Sampling

Sampling enables researchers to choose a group of individuals who are suitable for data collection and analysis. It is paramount that collection of data is relevant to the key themes of the research and the research design/strategies. The most basic sampling methods entail either probability or random sampling, which gives equal opportunity for selection to the entire sample population; as opposed to non-probability or non-random sampling, which requires a specific rationale for the inclusion or exclusion of sample groups of a population. Prior to the consideration of selecting appropriate methodologies and data collection techniques, the distinction between different sampling methods determined the selection results (Smith, 2015;Taherdoost, 2016). Sampling design identifies the nature and quality of the research, as well as the availability of secondary information sources (Reynolds et al. 2014; Gast and Ledford, 2014). The ideas behind a specific sampling approach vary significantly, and reflect the research objectives and questions in a certain degree (Palinkas et al. 2015). Whether probability sampling can be implemented will depend on the target population (Blaikie, 2010).

Techniques for probability sampling methodology options are set out in Table 2:

My research employed Opportunity probability sampling technique, due to the scarcity and inaccessibility of the target population. The sample will be carefully selected based on expatriates’ knowledge and experience in different relevant areas, such as human resources development, international business management, cross-cultural training, HR consultancy, global franchising, and international marketing.

Data analysi

Qualitative research methodology research involves analysing information from a subjective perspective, thereby relating different experiences to predetermined outcomes. In my research, thematic analysis will be applied in order to conduct qualitative data. In addition, the analysis of quantitative data will also include visualizations, such as Frequency tables and charts, aim to emphasise different experience and perspectives of the respondents. The results from the informal interviews will be transcribed, organized, analysed, in order to discover the prevalence of important themes. The results will be triangulated with literature review and case study findings, in order to relate to the research issues and key questions. Frequency tables are designed for representing the frequency of individual research responses. Categorized responses enable the determination of the number or proportion of agree/disagree statements form the surveyed participants, meanwhile demonstrate the frequency percentages of each response. Afterwards thematic analysis will be employed to isolate and relate different patterns highlighted by the findings. Thematic analysis, used as a form of analysis for qualitative research studies, provides a protocol for identifying, examining, compiling, describing, and reporting themes found within a data set (Braun and Clarke, 2006).

Justification of Analysis Methodolog

In the data analysis of qualitative research studies, researcher used primary data which is fundamentally disorganized and manifests as singular opinions. It is essential to organize it, break it down, synthesize it, and search for specific patterns that highlights what is important, as well as what is to be noted, and decide how the information is presented in such a way that the reader will understand (Bogdan and Biklen, 1982). Qualitative studies tend to produce large, often unstructured amounts of data, and analysis can sometimes be problematic (Turner, 1983), but they offer the researcher the opportunity to develop an idiographic understanding of participants, and what it means to them, within their social reality, to live with a particular condition or be in a particular situation (Bryman, 1988).

Leadership competencies

The performance of leaders are influenced by their leadership competencies as they show in their workplaces. Leadership is a key factor to determine marketplace success, covers every aspects of the company and play a critical support role within the organization (Chi and Pan, 2012; Roy, 1977). Qualified leaders are able to deal with all kinds of demands and perform multiple tasks apart from coping with clinging and complicated work place circumstances. They often work at intense levels for a longer period without showing negative performance and cognitive competence, they are also good at working under stress (Kets de Vries, 1989). There are a number of listed competencies that are important to take into consideration if leaders want to successfully perform their duties (Wood and Vilkinas, 2007). This includes having an achievement orientation attitude, a humanist method, keeping of positive perspective and an incline to comprehensiveness, honesty and self-awareness. Those elements play equal role in regard of how leaders perform within the organization. Emotional intelligence is another essential factor that define leader competence (Adler, 2008; Schlaerth et al. 2013). Researchers have discovered that successful leadership is influenced by emotional intelligence (Goleman et al. 2004; Macaleer and Shannon, 2002; Schlaerth et al. 2013; Wolff et al. 2002). Emotional intelligence also associates with the competence of managing conflict (Schlaerth et al. 2013). The study of emotional leadership has progressed to transformational leadership, particular in the work place (Schyns and Meindl , 2006). Aiming to manage self and staff’s emotions in order to achieve the tasks is an emotional method in leadership strategy (Schyns and Meindl, 2006). In other terms, establishing a good relationship between leaders and their staff as well as integrating a soft humanistic approach is pivotal as it not only motivates staff, but it also ensures that they will work to their full personal potential. There are five elements that are used to illustrate emotional intelligence: self-control, self-awareness, social abilities, compassionate and motivation (Cherniss and Goleman, 2001). All five elements are crucial for leadership skills (Boyatzis and McKee, 2005; Goleman et al. 2002). How leaders interact with followers reflect the quality of the leaders in the emotional awareness aspect (Wong and Law, 2002). Leaders who are highly emotional intelligent can use their emotions to improve their decision and motivate staff during the interaction (George, 2000). According to Mumford et al (2007), there are four distinct leadership skills: cognitive skills, business skills, interpersonal skills and strategic skills. The cognitive skills are relevant to data collection, information processing and distribution (Zaccaro, 2001). Interpersonal skills do not only require interacting and being involved with staff, it also focuses on the leader playing a more influential role (Cheruvelil et al. 2014; Katz, 1974; Mumford et al. 2000a). The business skills can be seen as the ability to manage resources such as employees, facilities and finances (Agbim, 2013; Katz, 1974; Luthens et al. 1988; Copman, 1971). The strategic skills are related to having the whole picture, recognizing issues and generating solutions (Conger and Kanungo, 1987; Dr es and Pepermans, 2012; Cox and Cooper, 1989; Yukl, 1989; Mumford et al. 2000b), while at the same time, having the ability to identify the causes and impacts of the problems (Mumford et al. 2000a).

Transactional and transformational leadership theories

Leadership style is the method applied to generate strategies and encourage people to achieve the expected results. If the managers give the full authority to the employees, without disturbing goals and assisting them to make decisions, then this kind of management is not sufficient, job satisfaction and productivity decline, employees are easily to get frustrated (Bass, 1990). Leaders are usually seen as autocratic or democratic. The circumstances, the type of the tasks and the skill level of the employees play important part in determining which leadership style should be used (Zenger and Folkman 2002). Different leadership style can lead to frustration and conflict in multinational organization (Gabrielsson et al. 2009). The early development of leadership style is transactional, when managers settle a certain agreements with the employees. Transactional leadership is about the exchanges between the managers and their subordinates, the punishments and rewards are aim for the control (Bass and Avolio 1994; Dubrin and Dalglish 2003). De Vries (2001, p. 252) calls transactional leadership a ‘mundane contractual exchange based on self interest’. In many situations, transactional leadership is the reflection of moderate (Vecchio, 2002). Transactional behaviours are important to keep the organization functioning by satisfing people’s requirements, but is not effective for motivating staff. In other word, this type of leadership can only keep the organizations operate in normal situation (Antaraman, 1993; Dunford, 1997). However, transactional leadership cannot encourage innovation, thus in the times of change and in the circumstances are unstable, it is unsuitable to use. Theorists in the past have already come to a conclusion that transactional leadership is not sufficient in the fast-changed dynamic world. They realised that leaders should be outstanding in order to provide the competitive advantage to their organization. Therefore, the imminent leadership style should help the organization to have an extraordinary performance, and a charismatic leaders should help the organization achieve this goal. In the early twentieth century, Weber has an ideal of charismatic leadership. Weber sees charismatic leaders are talented people with high esteem and have special influence towards their followers. Charisma is a character that enable a person to stand out from the crowd (Dubrin and Dalglish, 2003). A charismatic leader is described as someone who can resonate with their followers and form a give and take relationship by showing respect, giving trust and credibility (Popper and Zakkai, 1994, p. 4). Charisma leaders are able to be the role model to employees, not only encourage them to reach their biggest potential, but also help them to build self-esteem, therefore, employees feel that they are valued by the company, and can stay positive and always sense the hope. As a result, they can transform into loyal and conscientious team of followers (De Vries, 2001; Dubrin and Dalglish, 2003). Charismatic leaders are suitable in the time of radical change (Bass, 1990). The purpose of charismatic leaders is to influence people to do whatever they are required to do. However, there are disadvantages of this type of leader: for instance, they tend to neglect how much tasks are actually completed, so the productivity of the employees are relatively low. In addition, if the leaders have unethical agenda, they can bring the organization into downfall. Recently, a new leadership style called transformational leadership style has occurred, firstly advocated in 1973 by Downton (Bass and Avolio, 1994). The aim of this type of leadership is to emphasis what is accomplished instead of the personal charm of the leaders (Dubrin and Dalglish, 2003). Transformational leadership is suitable for the time of change (Antaraman, 1993). Leaders have the whole picture of voluntarily devote themselves to promote equality and authorization (Dubrin and Dalglish, 2003). Meanwhile, they encourage staff to have a new perspective toward their works (Bass and Avolio, 1994; Baker, 2001; De Vries, 2001; Sweeney and McFarlin, 2002; Vecchio, 2002). By comparison to charismatic leadership style, the charismatic is only just one small aspect of this type of leadership style (Sweeney and McFarlin, 2002). They also focus on managing and generating change. Similar with charismatic leaders, transformational leaders are also seen as charismatic, they are good at motivating people. Followers with this kind of leaders are feeling understood and normally inspired to exceed their potential. To conclude, transformational leaders are the leaders who can make the employees realize the need for change and evaluate the benefits of the change. For a long run, transformational leaders motivate workers to give priority to the organisation’s profit, pursue self-fulfiment and make them to work effective under a sense of urgency (Dubrin and Dalglish, 2003). Leadership study for the past 100 years has given the impression that leaders are born but not made. In fact, good leaders can definitely be trained. Leaders are responsible for the organizations and the subordinates transformations in this competitive era.

Successful leadership behaviours

There are five elements of successful leadership behaviours: “Modeling the way’’, ‘‘Inspiring a shared vision’’, ‘‘Challenging the process’’, ‘‘Enabling others to act’’ and ‘‘Encouraging the heart’’ (Kouzes and Pozner, 1987). “Modeling the way’’ means leaders should be a role model to their followers. “Inspiring a shared vision’’ suggests that leaders have to set a future goal for their followers, in order to gain mutual interest within the organisation as well as with their followers. This in turn will encourage the followers to contribute to the organisation. ‘‘Challenging the process’’ shows leaders are able to challenge organizational rules and take risks. ‘‘Enabling others to act’’ is about giving authorization and building trust among followers. ‘‘Encouraging the heart’’ is related to offering good feedback in regard of followers’ achievements.

Leadership innovation

Ravichandran(2000) states that there are two main types of innovation: one is relevant to the product and the market, while the other one is related to the organisation itself (Elenkov and Manev, 2005; Hoffman and Hegarty, 1993). The first type of innovation contains various of activities: launching new product design, developing new markets or initiating new programs. The second type of innovation involves projects such as changing structures of the organization, planning and training (Damanpour and Evan, 1984; Kimberly and Evanisko, 1981). Expatriate mangers are responsible for processing both innovation type. Because their duties involve introducing headquarters’ products, policies and services to a brand new market in the foreign country, meanwhile participate in the innovation process. Leaders can encourage innovation by different influential strategies (Mumford and Licuanan, 2004; Mumford et,al 2002). There are few categories of strategies can be practiced: one is about leading employees, another one is leading work. Leading employees means leaders can encourage creativity of employees, and employees creativity is crucial for the further market and organization innovation (Mumford et,al 2003). Leading employees can be completed by encouraging employees to value innovation, inspiring them to learn from the mistakes they made caused during the initial innovation process, motivating them to participating the innovation projects. In the second category of strategy, leaders can innovate organisation’s structure. Leaders can enable the employees to focus on the long-term picture, and devote to the innovative goals (Amabile et al. 2004). Leaders can even encourage entrepreneurial ideas of the employees. In a study of 66 cases in expatiate adjustment for over more than two decades, Bhaskar-Srinivas et al. (2005) obtained evident support for the Black-Mendenhall-Oddou model. Expatriate efficiency is a close aspect to expatriate adjustment, it is a difficult aspect to define, due to the complicity of various stakeholders, competing requirements, cooperation over time and the inexplicitly to work in unfamiliar and uncertain surroundings (Harrison et al. 2004). Stroh (2004) suggested there are two aspects of expatriate performance, one is managing interpersonal relations, another one is managing the given tasks from headquarters.

Expatriate adjustment research

Expatriate adjustment is the primary area in expatriate research. Early research in the 1960s and 1970s only focused on military crew, Peace Corps volunteers and other governmental workforce, however, this changed in the 1980s where the research focus shifted to business expatriate, where a noticeable growth was seen from 1990 until now. Black et al. (1991) famous research framework consisted of three categories of adjustments: interaction adjustment, work adjustment and general adjustment. They believe that there is a period called ‘‘anticipatory adjustment’’ before expiration, ‘‘anticipatory adjustment’’ is not always the same, it depends on what kind of employees and companies expatriates work with, and it is also influenced by the following variables: occupation sectors, individual conditions, organization network. Each of these categories can directly impact the three categories of adjustment. The first model about expatriates adjustment would be Adler’s model(1975), his model is regarded as the first one mentioned leadership transformation. According to him, there are five steps: contact with the other culture, disintegration, reintegration, autonomy, and independence. After twenty years, Osland(1995) recognised four categories of changes that American expatiates have experienced. Positive changes include culture sensitivity, tolerance, assertiveness, independence and flexibility. Meanwhile she discovered increase in cautious. Changes of attitude entails increased respect of different cultures, appreciation of life in general, broadened horizons toward the world. Progressed work skills are in interpersonal relations as well as communication skills. There was also the flexibility in different managerial style. Enriched knowledge include not only business but also encompassed political, economic.

Cross-cultural leadership adjustment theor

Recent studies focus on the importance of leadership adjustment (Tsai et al. 2019). One of these theories is situational leadership theory (SLT) (Hersey and Blanchard, 1969, 1993), which suggests that leaders should apply their leadership style according to the tasks given, which is referred to as ‘task-relevant maturity’. For instance, the leader should use instructive method in the situation when subordinates in a lower level of maturity, while use more delegating style to deal with followers with high maturity (Tsai et al. 2019). This theory combined both path and contingency leadership theories, which added additional elements like relationships between leaders and followers, task structures, and the level of motivation (Fernandez and Vecchio, 1997; Graeff, 1983; House and Mitchell, 1975). The second theory emphasises the culture influence on leadership adjustment issue (CLTs) (House et al. 2004). CLTs covered cross-cultural leadership issues which have not been mentioned in SLT. The theories stressed that the perceptions of leadership are relevant to the leaders’ cultural background (Javidan et al. 2006; Oc, 2017; Scandura and Dorfman, 2004). The theory points out that the adjustments of leadership strategies should follow the expectation of their subordinates’ culture. This also indicates that expatriate managers will need to alter their leadership style in order to match their subordinates’ culture. However, these studies neglected to mention the role of subordinates within these changes when interacting with managers who are from a different culture to them. Furthermore, strategies need to be considered when dealing with cross-culture working environments.

There are some significant findings in regard of leadership effectiveness in the cross-cultural settings. The first finding is developed by Scandura and Dorfman (2004), who state that the effective leadership approach in Western cultures is often ineffective in Eastern cultures, that is because of the contradictories between individualism and collectivism belief between Western culture and Eastern culture. This conflict can also be found in the scenario when a manger is expected to listen carefully to the subordinates (Jones et al. 1990). This behaviour is generally advocated in the West, In Malaysia, leadership traits such as modesty and humility are important, which is opposite to the confidence and individual personality in the United States (Den Hartog et al. 1999).

Work role transition theory (WRT) (Nicholson, 1984) is a crucial mode in explaining and predicting the way in which leaders change their behavioural approach in a new position or career status (Black et al. 1991; Dawis and Lofquist, 1984; Nicholson, 1984; Zhu et al. 2016). Dawis et al. (1984) termed as “modes of adjustment.” There are two types of adjustment for the managers, one is “active adjustment”, which managers adapt in the process of environment change; another one is “reactive adjustments”, which managers change themselves in order to meet their environmental conditions. Their research initially focused on work related problems which lead to active or reactive adjustments. According to Nicholson (1984), there are two dimension for leaders to adjust into their new roles. The two dimensional changes are relevant to both personal development and occupational development in the workplace. The first dimension explains the potential improvement in personal development when getting a new role or environment, including components like individual belief, behaviours, skills and leadership. The second dimensions illustrates the changes as a consequence of role change, which contains attributes such as interpersonal relationship and work approaches (Tsai et al. 2019). People tend to adopt to new roles in the following approaches: replication, absorption, determination, and exploration (Nicholson, 1984). Replication is when leaders’ adjustments are minimal due to the similarity between their former role and their current role (Brett, 1980). Absorption happens when the leaders recognized the necessity to change their behaviour in order to fit the new role they have been given. Determination is the complete opposite to Absorption, as the leaders prefer the role adapts to them. Exploration occurred when both sides adjust to the new role.

Nicholson suggested that there are two types of work demanding including in the choice of the four modes. The first one is related to individual’s ability in adjusting task content (such as interpersonal relationship, leadership practices and work targets). If individual have sufficient chance/ability to modify those task content, they would choose exploration or determination modes of adjustment, while limited opportunity/ability in modifying the task content for individual would cause absorption or replication adjustment modes. The second one is relevant to role similarity, is defined as ‘the degree to which the role permits the exercise of prior knowledge, practiced skills and established habits’ (Nicholson, 1984, p. 178). The more similarities prior role had with current role, the less pressure individuals are facing. The high similarity lead to exploration or absorption modes of adjustment, while the low similarity cause determination and replication modes of adjustment.

How to turn cultural divergent from a challenge to an opportunity is the biggest difficulty faced by the global leader (Schneider and Barsoux, 2003). They believed in doing so is essential to maximize the possibility of the alliances between borders, as it gives the flexibility to cope with the fast-changing and dynamic global economy. According to Søderbergand (2002), the correct management of cultural difference is very likely to achieve the competitive advantage and increase the wholesome level of the company.

Most research about cross-cultural leadership highlight the impact of cultural background on leadership style (Brodbeck et al. 2000). Especially the research of expatriates are able to give the ideas on how leadership behaviour can change to meet the requirements of different cultures (Zimmerman and Sparrow, 2007).

One research conducted by Tsai et al. (2019) applied Nicholson’s theory WRT, to examine how different leadership adjustment modes influence expatriates’ decisions on choosing their leadership strategies. The research applied a thorough study on expatriate managers who are from twenty five countries in Thailand, and they found the most popular mode is exploration mode among the managers, as 79 per cent of expatriates chose this mode, which means they are constantly adjusting their leadership styles in order to meet the local culture, the research also discovered that expatriates managers are not the only side that has changed, their subordinates had changed their behaviours as well. This finding underpinned the projection from WRT theory that leadership adjust around the culture is inevitable, because the cultural background between new leaders and subordinates is different.

Work role transition theory (WRT) (Nicholson, 1984) is a crucial mode in explaining and predicting the way in which leaders change their behavioural approach in a new position or career status (Black et al. 1991; Dawis and Lofquist, 1984; Nicholson, 1984; Zhu et al. 2016). Dawis et al. (1984) termed as “modes of adjustment.” There are two types of adjustment for the managers, one is “active adjustment”, which managers adapt in the process of environment change; another one is “reactive adjustments”, which managers change themselves in order to meet their environmental conditions. Their research initially focused on work related problems which lead to active or reactive adjustments. According to Nicholson (1984), there are two dimension for leaders to adjust into their new roles. The two dimensional changes are relevant to both personal development and occupational development in the workplace. The first dimension explains the potential improvement in personal development when getting a new role or environment, including components like individual belief, behaviours, skills and leadership. The second dimensions illustrates the changes as a consequence of role change, which contains attributes such as interpersonal relationship and work approaches (Tsai et al. 2019). People tend to adopt to new roles in the following approaches: replication, absorption, determination, and exploration (Nicholson, 1984). Replication is when leaders’ adjustments are minimal due to the similarity between their former role and their current role (Brett, 1980). Absorption happens when the leaders recognized the necessity to change their behaviour in order to fit the new role they have been given. Determination is the complete opposite to Absorption, as the leaders prefer the role adapts to them. Exploration occurred when both sides adjust to the new role.

Nicholson suggested that there are two types of work demanding including in the choice of the four modes. The first one is related to individual’s ability in adjusting task content (such as interpersonal relationship, leadership practices and work targets). If individual have sufficient chance/ability to modify those task content, they would choose exploration or determination modes of adjustment, while limited opportunity/ability in modifying the task content for individual would cause absorption or replication adjustment modes. The second one is relevant to role similarity, is defined as ‘the degree to which the role permits the exercise of prior knowledge, practiced skills and established habits’ (Nicholson, 1984, p. 178). The more similarities prior role had with current role, the less pressure individuals are facing. The high similarity lead to exploration or absorption modes of adjustment, while the low similarity cause determination and replication modes of adjustment.

How to turn cultural divergent from a challenge to an opportunity is the biggest difficulty faced by the global leader (Schneider and Barsoux, 2003). They believed in doing so is essential to maximize the possibility of the alliances between borders, as it gives the flexibility to cope with the fast-changing and dynamic global economy. According to Søderbergand (2002), the correct management of cultural difference is very likely to achieve the competitive advantage and increase the wholesome level of the company.

Most research about cross-cultural leadership highlight the impact of cultural background on leadership style (Brodbeck et al. 2000). Especially the research of expatriates are able to give the ideas on how leadership behaviour can change to meet the requirements of different cultures (Zimmerman and Sparrow, 2007).

One research conducted by Tsai et al. (2019) applied Nicholson’s theory WRT, to examine how different leadership adjustment modes influence expatriates’ decisions on choosing their leadership strategies. The research applied a thorough study on expatriate managers who are from twenty five countries in Thailand, and they found the most popular mode is exploration mode among the managers, as 79 per cent of expatriates chose this mode, which means they are constantly adjusting their leadership styles in order to meet the local culture, the research also discovered that expatriates managers are not the only side that has changed, their subordinates had changed their behaviours as well. This finding underpinned the projection from WRT theory that leadership adjust around the culture is inevitable, because the cultural background between new leaders and subordinates is different.

Hofstede culture dimension theory

Culture has become more and more important in both research and practice in the last two decades. The most prominent theory is Hofstede (1980a, 1991) culture framework.

Individualism vs. collectivism (IDV)

One dimension was thoroughly researched by Hofstede (1980a, 1980b, 1991) and other researchers (Yeh and Lawrence, 1995) that signified a considerable factor in the study of national culture: Individualism and collectivism. Individualism represents a loosely knit social framework, people in individualism society are suppose to look after themselves and their close families, and to some extent, individuals think themselves are more important than the collective. In comparison, collectivism is distinguished with a tight social framework, people categorised by groups. The benefit of groups is generally more important than that of individuals. Individuals societies are characterised with separateness and explicitness (Hall, E.T. 1981), also featured with structure, order and precision. The upbringing of individualism is related to rationality and positivism, and seeking orders via controlling and clarifying. Individualism generated the perspective of free will, which authorised managers to have a relatively big influence towards the organizations. As a result, most of the organizational science is built upon the prediction that managers’’ behaviors can make a difference within the organizations (Child, 1972). Collectivism has the preference of analyzing environment, and controlling the situation within the organization. Consequently, managers have to analyse the situation before strategically planning ahead.

Power distance index (PDI) and Uncertainty avoidance (UAI

Hierarchical (power distance) evaluates how people’s attitude in the society differ toward inequality (Haire et al. 1966). High degree of hierarchical differentiation means people are more tolerate to social inequality compared to people in low level of hierarchical differentiation (Hofstede, 1980). Whether the public accept social inequality, is greatly related to social status, which reflects that social power is unfairly allocated within the society. People who obtained high social power enjoy the privileged and convenient life, and have control over the people with less social power. Observationally, high degree hierarchical differentiation is relatively more tolerate towards the control form high status (Bond et al., 1985), and has more tolerate attitude towards unequal power distribution within the society (Hui et al. 1991). Explicit contracting (uncertainty avoidance) reflects the preference of formal or informal communication (Glenn and Glenn, 1981; Gudykunst and Ting-Tbomey, 1988; Hall, 1976). In certain cultures, information tend to be delivered through explicit codes, whereas in other cultures, less information have to be transmitted by coded messages (Hall, 1976). Early on, researchers have discovered this dimension illustrated culture divergence in conflict management (Ting-Toomey, 1985).

The history of expatriate leadership research

During the period of 1960 and 1980, the research about cross-cultural management concentrate on organization systems and employee behavior. Because the research mainly based in the US, other countries outside America are regarded as foreign and other cultures in comparison to America culture. After the World War II, more and more firms were seeking oversea opportunities to enhance career development. During this period, research began to cover how cultures, policies, law and business were operated in other countries. International division and subsidiary in other countries had gradually appeared, expatriates started to emerge, there were large number of them sent from headquarters to oversea subsidiaries, in order to instruct and inspect local workers. Cross culture research during this time was mainly focused on the culture difference, and how to assist expatriates adapting into the host country culture. However, research on how to support local employees cooperating with expatriates had been overlooked. In the end of this time, with Europe were retrieving from WWII, Japan had become considerable exporter. In the world, two shifts took place. First of all, the US companies had lost their competitive advantages in International markets, resulting in the loss of confidence. In comparison to the disadvantaged US companies, Japanese management techniques had become the center of interest. As a result, researchers also started to focus on Japanese models about management strategies (Mendenhall and Oddou, 1986; Ouchi, 1981). Following this, international companies started doing business with more than one country, meanwhile the progress of computer technology and telecommunications provided the opportunities to link headquarters and subsidiaries. The technology evolution put culture in a significant position. During the period of 1980 and 2000, with the progression of the organisational systems such as “matrix” and “regional”, the job requirements for expatriates had increased dramatically, as a result, enhancing skills in order to cooperate successfully with local staff became necessary. Detached leadership style had become old-fashioned, engaged leadership style started to become prominent. There are plenty of research had developed according to this change in leadership style. In the 1990s, the structure of the organisation remained mostly same in the research paper, but around the world, it had been globalised, which revealed in the late 1990s with Bartlett and Ghoshal (1992) publications about transnational organization. Although the designs of the transnational organization structure had not appeared on paper, for the majority of global managers, the nature of their work had become transnational. The characters of globalisation like complexity, multiplicity, interdependency and flux (Lane et al. 2004) required expatriates to adapt new global leadership strategies. Under these circumstances, it is vital for expatriate managers to give up control and incorporate shared values. As a result, cultural awareness had become increasingly important. Before 1980, research focus was very much the same in nature, but can be vary from culture to culture (Hall, 1966; Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck, 1961). However, noticeably, the appearance of Hofstede’s (1984) culture dimension theory, lead to the major focus on management/organisational behaviour research, particularly in the region of leadership. A large amount of research within this particular field continued to develop between 1980-2000. There is a transformation not only in cross-culture research, but also in some sub-fields of international business, from implicitly to much more explicitly research context in the globalisation direction. From the beginning of 21st century, global teams in MNCs are normal phenomenon for leaders (Zander et al. 2012), due to global scheme and global enterprise, managers who located in the home country are also facing multicultural teams, which is the similar situation with expatriates who work abroad. The work demanding of expatriates is to lead the staff from any culture background, at any time needed, in any locations around world. Moreover, the skills required of them are not only represented in the cross-culture leadership research, a wider range of skill sets are demanded from them. Take culture awareness as an example, is in need of extended interpretation of culture system, and how to manage relevant culture in the right multicultural contexts(Salk and Brannen, 2000). Adler(1983) suggests there are three categories of cross-cultural management research: intercultural, comparative and unicultrual. Intercultural research concentrates the communication between two or more countries. For instance, how to communicate effectively for British expatriates, with the employees in India. Comparative research focuses on enterprise management in two or more countries, and what are the similarities between them. For instance, how to manage conflicts in Denmark, Peru and Japan. Unicultrual examines enterprise management in one country. For instance, management in a Polish company. Overall, Unicultrual research were the most popular among three type of research, as it occupied 48 per cent among all the relevant research articles Adler discovered.

Selection criteria for expatriate leaders

In the past, companies concentrated on technical skills, experience and whether expatriates themselves wanted to work abroad (Anderson, 2005; Graf, 2004; Mendenhall et al. 2002). According to several scholars, although some expatriates have prior leadership experience in their home countries, this does not predict that they will have an advantage to work in the host countries (Miller, 1975; Black et al. 1999). However, there is a set of personality traits that can predict good performance, which including driven, confidence, willingness of taking risk (Ruben, 1989). Moreover, the personal preference of working abroad is also very important (Tung and Varma, 2008), but it cannot guarantee the success of the assignment. Although technical competence is essential, it is not enough to guarantee the successful assignment either (Tung, 1981; Varma et al. 2002). Research discovered that personality traits are closely related to high performance. For instance, The Five Factor Model of personality (Costa and McCrae, 1992) found o that agreeableness, extraversion and emotional stability are the elements contributing to successful adjustment and performance (Shaffer et al. 2006). Ethnocentrism can create an obstacle for successful adjustment and performance (Caligiuri and Di Santo, 2001). Mol et al. (2005) used 30 examples to evaluate expatriate overseas performance, then discovered that four out of five from The Five Factor Model with culture awareness and language ability were predicting factors of good expatriate overseas performance. Furuya et al. (2009) found that personality traits are relevant to intercultural ability were predictive factors of expatriate performance and post-repatriation performance.

Expatriate leadership qualities

Many expatriate leadership qualities involve communicating between differences, as a result, intercultural communication has become one of the aspects in expatriate research. The research of intercultural communication focuses on effective behaviours. Defined as ‘‘the ability to effectively and appropriately execute communication behaviours that negotiate each other’s cultural identity or identities in a culturally diverse environment’’ (Chen and Starosta, 1998, p. 28). The skill requirements for intercultural competence include tolerance of ambiguity, cross-cultural empathy, flexibility and mindfulness (Gudykunst ,1994). Mindfulness is one of the expatriate leadership quality, which is the ability to open to new experience and divergent perspectives (Langer,1992). Being mindful is to value emotions of the person who you are communicating with. Flexibility as an expatriate leadership quality includes both cognitive and behavioural flexibility. Cognitive flexibility is the ability to consider various of opinions in order to acknowledge of the situation. Behavioural flexibility is the ability to choose sensible decision and suitable actions (Bird, 2013). Tolerance of ambiguity is another expatriate leadership ability to accept ambiguity, inexplicitly (Budner, 1962). As for expatriate leaders, they are expected to be intercultural tolerant, which is to value diversity, cope with changes, deal with unfamiliar environments, manage contradictory perspectives (Herman et al. 2010). The last expatriate leadership quality is cross-cultural empathy, which is an competency to experience different cultures (Bennett ,1993).

Fiedler’s research in 1967 is the first comparative leadership research reflecting on two or more cultures. He drew a conclusion that culture can influence the way leaders interact with subsidiaries. Then, the famous Hofstede research on culture dimension increased the research on culture dimension (Fiske, 1992; Hall and Hall, 1990; Hofstede, 1984; Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck, 1961; Schwartz, 1992; Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner, 1998). The second version of Hofstede’s (2003) involved over two thousands comparative research. The comparative leadership research have discovered a serious of divergence in leadership behaviour under different culture circumstances. For instance, leaders and companies are more likely been identified by their followers in collectivist cultures rather than individualistic cultures (Earley, 1989; Triandis, 1995). Leaders are more likely to be dictatorial in the culture which has high power distance rather than the culture that has low power distance (Adsit et al. 1997). In addition, comparative leadership research also tried to acknowledge of the suitability about some particular research in diverse culture context, by using theoretical based research methods. For example, participative leadership style was less potent in cultures which has high power distance (Newman and Nollen, 1996; Welsh et al. 1993). However, some characters of transformational as well as charismatic leadership, like encouraging, trustworthy, dynamic, positive, confidence, motivational, worked in most cultures (Den Hartog et al. 1999), Which indicates some leadership styles are generally effective.

GLOBE study made a great contribution to present various of different leadership style applied under dynamic cultures (Den Hartog et al. 1999). Because business conducting, technical methods as well as education levels are become more and more similar, there is also a rising convergence in preferred leadership style. There is a shift from comparative leadership to global leadership from GLOBE researchers. As mentioned in the chapter above about expatriate leadership qualities, tolerance of ambiguity, flexibility and mindfulness are necessary qualities for effective expatriates leadership (House et al. 2006). More recent research has focused more on a broader acknowledgment of global leadership (Dorfman et al. 2012). The comparative leadership research is not only covered leadership styles in individual countries, but also focused on how leadership style differ from convergent or divergent cultures in other countries. Especially GLOBE research, it has recognised the general acceptable and unacceptable features. These findings are particular useful for multinational companies to select expatriates, as they provided the preferences and expectations of host country. In fact, expatriates who work in dynamic culture environments have a better understanding in terms of what kind of adjustments are needed. Mintzberg (1973) suggested seven managerial roles: liaison, leader, spokesperson, monitor, decision maker, negotiator, innovator. How managers conduct the roles was controlled by circumstances, people and occupation sectors. The reason why there are more job requirements for expatriates leaders than that for domestic leaders, is because there are more skill requirements for expatriates. For instance, expatriates are required to be emotional stable and driven. In addition, they need to have more flexibility and adaptability towards cultures, and to have more capability to accept various of perspectives. Moreover, due to their special working environments, their role requirements involves a larger percentage of innovation, negotiation, decision- making and pressure management (Deal, 2002). Spreitzer, McCall, and Mahoney (1997) pointed out that searching and applying feedback, openness to learning, being insightful, accept criticism and being flexible are important characters for expatriates leaders to be successful. The first quantitative research about leadership competencies is Yeung and Ready’s (1995) research, their research involves 1200 respondents who work in 10 different companies over 8 countries. The discovered competencies are: having an overall vision, the ability to think of strategies to solve issues, participate in culture/strategy change, results/customer orientated, empowerment to others.

Global leadership competencies covered a wide range of qualities. From personality perceptive, inquisitiveness and optimism are advocated. From orientation perspective, results orientation is preferred. As for cognitive ability, intellectual intelligence and cognitive complexity are recommended. From motivational inclination aspect, motivation to learn and determination are advised. As for knowledge bases, global business knowledge as well as technical skills are required.

Bird‘s (2013) review during 1993 and 2012 on global leadership competencies, he documented 160 competencies, which introduced within organizational framework (Bird and Osland, 2004; Brake, 1997; Kets de Vries and Florent-Treacy, 1999; Morrison, 2000), and are separated equitably within three main categories: 55 are Business and organisational category, 47 are people and Relations category, 58 are self-management category.

Caligiuri(2006) on global leadership competency research analysed the job requirements of leaders, then identify what competencies, knowledge and skills are necessary based on the job requirements. She suggested there are ten global leadership engagement, which include cooperate colleagues from foreign countries, communicate with overseas customers, the ability to speak foreign language at work, supervise staff from different countries, develop plans with precise world-wide scope, mange budgets, negotiations, manage overseas suppliers and vendors, risk management. After Caligiuri, Caligiuri and Tarique (2009) discovered that leadership effectiveness was presented in leadership activities like expatriate assignments, international meetings and working with multinational teams. Subsequently, Caligiuri and Tarique (2012) discovered that cross culture competence has positive impact on global leadership effectiveness, which was supported by characters such as openness, low neuroticism and extrovert.

Take a deeper dive into Identity and Influence with our additional resources.

Expatriate Success

Expatriate success can be defined as the eventual success of overseas assignments for which expatriates are sent to. The ability for individuals sent on overseas assignments to be able to effectively blend in the host country and culture and assimilate the required characteristics leading to the success of the mission for which expatriation was established (Ross, 2011). According to Goby (2002), a significant discrepancy exists between perception of expatriate success and its determinants between the expatriates themselves and the HR department of the multinational corporations. This ultimately impacts a wide scope of success factors for expatriate assignments including personal factors such as language, personality, employee welfare and compensation as well as support factors such as company expatriate support. These factors are further impacted by the current Covid-19 pandemic which has had significant impact on the world economy and conventional business management and practices.

According to Goby (2002), a significant discrepancy exists between perception of expatriate success and its determinants between the expatriates themselves and the HR department of the multinational corporations. This ultimately impacts a wide scope of success factors for expatriate assignments including personal factors such as language, personality, employee welfare and compensation as well as support factors such as company expatriate support. These factors are further impacted by the current Covid-19 pandemic which has had significant impact on the world economy and conventional business management and practices.

Expatriates and Covid-19

The outbreak and spread of the Covid-19 pandemic has significantly impacted normal business activities in all the countries across the world including expatriate operations. While most expatriates already in assignment are settled within host countries and can continue with their work despite and because of the measures in place to minimize the diseases’ spread (Global Health, 2021), new challenges and disadvantages emerge and impact expatriate programs as a result of the covid-19 pandemic. According to Pardo (2020) highly active expatriates as well as organizations with active international transfers of expatriates were the most significantly impacted with a significant increase in levels of stress and impact on day to day life. This impact is generally associated with two main factors including: difficulty in planning and coordination between the global mobility teams in MNCs as a result of immigration and travel restrictions as well as the impact of stay at home working and lockdown orders (Pardo, 2020).

Given the covid-19 knowledge and the restrictions in place to minimize and eventually combat the diseases’ spread, internet connections provide a significant avenue and platform to enhance working capabilities and relationships. This is significant for the ultimate success of expatriates given that regardless of the inability to travel and be at work physically, individuals can still coordinate and organize their work and duties via online channels leading to significant eradication of the barriers as a result of the pandemic. Noman et al. (2020) advances that as a result of the fast globalization due to internet connections, individuals are living and working globally in a diverse cultural environment from their homelands. The internet connection and resources also enable expatriates to effectively and rapidly learn different languages used within their host countries to enable better understanding of other locals who they work with. This is in addition to exposing them to information on cultural differences and the various measures adopted by different areas of their host countries as a result of the covid-19 pandemic.

Looking for further insights on Health and Social Care Settings? Click here.

References

Global Health, 2021. The impact of coronavirus on expat life | Expats Blog. [online] Foyer Global Health. Available at:

Goby, V., Ahmed, Z., Annavarjula, M., Ibrahim, D. and Osman-Gani, A., 2002. Determinants of Expatriate Success: An Empirical Study of Singaporean Expatriates in The Peoples Republic of China. Journal of Transnational Management Development, 7(4), pp.73-88.

Noman, M., Sial, M.S., Brugni, T.V., Hwang, J., Bhutto, M.Y., and Khanh, T.H.T. (2020) Determining the Challenges Encountered by Chinese Expatriates in Pakistan, Sustainability, Vol. 12, Part 1327, pp 1-16.

Pardo, C., 2020. COVID-19's impact on expatriate management (via Passle). [online] Passle. Available at:

Ross, K., 2011. Characteristics of Successful Expatriates: Unleashing Success by Identifying and Coaching on Specific Characteristics Northwestern University | School of Education & Social Policy. [online] Sesp.northwestern.edu. Available at:

Achua, C. and Lussier, R. (2000), Leadership, Theory, Application and Skill Development, United States of America: SouthWestern College Publishing.

Adler, N.J. (2008), International Dimensions of Organizational Behavior, 5th ed., South-Western, Mason, PWS-Thomson.

Antaraman, V. (1993), Evolving Concepts of Organizational Leadership, Singapore: Singapore Management Review.

Ashamalla, M and Crocitto, M.(1997), Easing entry and beyond: Preparing expatriates and patriates for foreign assignment success, International Journal of Commerce and Management , 7(1) , pp. 106-114.

Bae, M. Kwon, I.W. Safranski, R. and Han, D.C. (1993), “Impact of Education and Other Contextual Factors on Management Values: a Study of Managers in the Republic of Korea”, in Essays in Honour of Professor Hi-Young Hahn, Seoul: Seoul National University Press. Baker, W. (2001), Breakthrough Leadership: Believe, Belong, Contibute and Transcend, Organizational Development Journal, 19(1), pp.80–83.

Banerjee, P. Gaur, J. and Gupta, R. (2012) , Exploring the role of the spouse in expatriate failure: A grounded theory-based investigation of expatriate spouse adjustment issues from India, The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23(17) , pp. 3559-3577. Bass, B.M. (1990), Bass & Stogdill’s Handbook of Leadership, New York: The Free Press. Bass, B.M. (1990), Bass and Stogdills Handbook of Leadership Theory Research and Managerial Applications, New York: The Free Press.

Bass, B.M. and Avolio, B. (1994), Improving Organizational Effectiveness Through Transformational Leadership, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Black, J.S. and Gregersen, H.B. (1991) , The other half of the picture: Antecedents of spouse cross-cultural adjustment. Journal of International Business Studies, 22(3) , pp. 461-477.

Bolino, M, C. (2007), Expatriate assignments and intra-organizational career success: implications for individuals and organizations, Journal of International Business Studies, Palgrave Macmillan, Academy of International Business, 38(5) , pp. 819-835.

Boyatzis, R. and McKee, A. (2005), Resonant Leadership: Renewing Yourself and Connecting with Others Through Mindfulness, Hope, and Compassion, Harvard Business Press.

Cherniss, C. and Goleman, D. (Eds) (2001), The Emotionally Intelligent Workplace: How to Select for, Measure, and Improve Emotional Intelligence in Individuals, Groups, and Organizations, 1st ed., Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA: The Jossey-Bass Business and Management Series,

Cheruvelil, K. Soranno, P. Weathers, K. Hanson, P. Goring, S. Filstrup, C. and Read, E. (2014), Creating and maintaining high-performing collaborative research teams: the importance of diversity and interpersonal skills, Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 12(1), pp. 31-38.

Chi, N. and Pan, S. (2012), A multilevel investigation of missing links between transformational leadership and task performance: the mediating roles of perceived person-job fit and person-organization fit, Journal of Business Psychology, 27(1), pp. 43-56.

Conger, J.A. and Kanungo, R.N. (1987), Towards a behavioral theory of charismatic leadership in organizational settings, Academy of Management Review, 12 (4), pp. 637-647.

Copman, G. (1971), The Chief Executive and Business Growth, London: Leviathan House.

Cox, C. and Cooper, C. (1989), The making of the British CEO: childhood, work experience, personality, and management styles, Academy of Management Executive, 3 (3), pp. 241-245

De Vries, M.K. (2001), The Leadership Mystique: A User’s Manual for the Human Enterprise, Harlow, England/New York: Prentice Hall/Financial Times.

Deresky, H. (2011) , International management: Managing across borders and cultures, 7th eds. Upper Saddle River, New York: Prentice Hall.

Doherty, N. and Dickmann, M. (2012) , Self-initiated expatriation: drivers, employment experience and career outcomes, In Andresen, M. Ariss, A. A. Walther , M. and Wolff , K. (eds) Self-Initiated Expatriation: Mastering the Dynamics, London: Routledge, pp. 122–142.

Dries, N. and Pepermans, R. (2012), How to identify leadership potential: development and testing of a consensus model, Human Resource Management, 51 (3), pp. 361-385.

Dubrin, A.J. and Dalglish, C. (2003), Leadership An Australian Focus, Milton, QLD: John Wiley and Sons.

Dunford, R.W. (1997), Organizational Behaviour: An Organizational Analysis Perspective, Sydney: Addison Wesley.

Edström, A. and Galbraith, J. R. (1977), Transfer of Managers as a Coordination and Control Strategy in Multinational Organizations, Administrative Science Quarterly, 22(2), pp. 248–263.

Forster, N. (1997), The persistent myth of high expatriate failure rates, International Journal of Human Resource Management, 8(4), pp. 430-445.

Gabrielsson, M. Darling, J. and Seristo, H. (2009), Transformational Team Building Across Cultural Boundaries, Team Performance Management, 15(5–6) pp.235–256.

George, J.M. and Zhou, J. (2002), Understanding when bad moods foster creativity and good ones don’t: the role of context and clarity of feeling, Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), pp. 687-697.

Goleman, D. Boyatzis, R.E. and McKee, A. (2002), Primal Leadership: Realizing the Power of Emotional Intelligence, Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press,

Goleman, D. Boyatzis, R.E. and McKee, A. (2004), Primal Leadership: Learning to Lead with Emotional Intelligence, Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Hall, Edward T. (1995), The Silent Language, New York: Anchor Books.

Han, D.C. Kwon, I.W. Stoeberl, P.A and Kim, J.H. (1996), “The Relationship between Leadership and Power among Korean and United States Business Students”, International Journal of Management, 13(2): pp.135-47.

Harvey, M. G. (1985) , The executive family: An overlooked variable in international assignments, Columbia Journal of World Business. pp. 84-93.

Hofstede, G. (1984), Culture’s Consequence, International Differences in Work Related Values, Beverly Hills, CA:Sage Publications.

Katz, R. (1974), Skill of an effective administrator”, Harvard Business Review, 52 (5), p. 90. Kets de Vries, M.F.R. (1989), Prisoners of Leadership, New York: Wiley.

Kraimer, M. L. Bolino, M. and Mead, B. (2016), Themes in expatriate and repatriate research over four decades: What do we know and what do we still need to learn? Annual Review of MNCsal Psychology and MNCsal Behavior , 3(1) , pp. 83-109.

Luthens, F. Welsh, D.H. and Taylor, L.A. (1988), A descriptive model of managerial effectiveness, Group and Organization Studies, 13 (2), pp. 148-162.

Macaleer, W.D. and Shannon, J.B. (2002), Emotional intelligence: how does it affect leadership, Employee Relations Today, 29 (3), p. 9.

Muenjohn, N. (2008), Leadership Concepts and Theories: Its Past and Present, Academy of International Business (AIB), 4-6 December in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Muenjohn, N. & Armstrong, A. (2007a), “Transformational Leadership: the Influence of Culture on the Leadership Behaviours of Expatriate Managers”, International Journal of Business and Information, 2(2): pp.265- 83.

Mumford, M. Zaccaro, S. Harding, F. Jacob, O. and Fleishman, E. (2000b), Leadership skills for a changing world: solving complex social problems, Leadership Quarterly, 11 (1), pp. 11-25.

Mumford, M.D. Marks, M.A. Connelly, M.S. Zaccaro, S.J. and Reiter-Palmon, R. (2000a), Development of leadership skills: experience and timing, Leadership Quarterly, 11 (1), pp. 87-114.

Mumford, T. Campion, M. and Morgeson, F. (2007), The leadership skills strataplex: leadership skill requirements across organizational levels, The Leadership Quarterly, 18(1), pp. 154-166.

Musasizi, Y. Aarakit, S. and Mwesigwa, R. (2016), Expatriate capabilities, knowledge transfer and competitive advantage of the foreign direct investments in Uganda’s service sector, International Journal of Economics, Commerce and Management, 4 (2), pp. 130-143.

Popper, M., and Zakkai, E. (1994), Transactional, Charismatic and Transformational Leadership: Conditions Conducive to Their Predominance, Leadership & Organizational Development Journal, 15(6), pp. 3–7.

Roy, D.A. (1977), Management education and training in the Arab word: a review of issues and problems, International Review of Administrative Sciences, 43 (3), pp. 221-228.

Schlaerth, A., Ensari, N. and Christian, J. (2013), A meta-analytical review of the relationship between emotional intelligence and leaders’ constructive conflict management, Group Process & Intergroup Relations, 16 (1), pp. 126-136.

Schyns, B. and Meindl, J.R. (2006), Emotionalizing leadership in a cross-cultural context, in Mobley, W.H. and Weldon, E. (Eds), Advances in Global Leadership, Oxford:Elsevier, Kidlington.