Graduate Education and Job Readiness

Chapter 1

1.0 Introduction

This chapter entails an overview of the research topic, questions to be answered, and a brief background study of graduate education in the UK as well as the subsequent Job market. According to a theoretical perspective by O’Conner, (2015) a career without involvement of its practical approach falls short of the market requirement leading to a difficulty for graduates to secure jobs, let alone be able to rise to managerial levels. In line with this, the study aims to evaluate the level of preparedness of graduates for managerial roles, specifically comparing the influence of traditional degree graduates versus apprenticeship degree graduates. The chapter will further highlight the study objectives as well as rationale.

1.1 Background of Study

A wide range of studies by different scholars and researchers including (Magdas et al. (2013) O’Connor (2015); Salas-Velasco (2007) highlight a significant challenge in transitioning of graduates from the school to the Job market. Clegg (2018) points out that approximately 53% of college graduates are unemployed or work in a job that does not require a bachelor's degree. It takes the average college graduate three to six months to secure employment after graduation and this is partly due to a lack of hands on experience with regards to what is required in the job market. O’Reagan (2010) further highlights that individuals who experience challenges in transitioning to the job market include individuals with a low career relevance and future focus. The lack of a practical aspect to their learning limit their imagination to what is expected as well as how they would want to progress with their careers in the future.

The Apprenticeship degree program and system include the response by the UK government in 2015, having recognized the significance and need of experience in education process for individuals to be more competent at their positions (Kirby, 2015). Through Apprenticeship degree programs, individuals can effectively gain knowledge and experience with regards to their careers, affording them a sense of direction and future focus with regards to career direction. This awareness and understanding effectively affect the transition from schools to the job market. However, what impact does it have in carer progression? The study will effectively investigate the job market in the traditional degree graduate market and the apprenticeship degree graduate market, evaluating the significant benefits and drawbacks of these systems as such highlighting a comparison in the graduates’ preparedness for managerial positions.

1.2 Research Problem

Having recognized a growing disconnect and difficulty in the transition from universities by graduates into the job market especially for young individuals, the UK government introduced the degree apprenticeships in 2015, to provide an alternative to traditional graduate degrees and smoothen the transition into the job market. However, school leavers have had a dilemma concerning whether to pursue a traditional degree or Apprenticeship degrees presenting another challenge in the transition period. In addition the job market is equally divided in terms of qualifications of these two education programs. While graduate degrees are more recognized by employers and are thus likely to promote graduate employees to management positions easily, securing jobs with a graduate degree in the current UK market presents a big challenge due to lack of the necessary experience and hands on skills required thereby effectively discouraging students from pursuing traditional degrees (Jackson, and Wilton, 2017). However, the apprenticeship degrees despite providing a wide range of experience and enabling one to practice as they learn thereby ensuring significant experience and hands on skills is limiting to their credentials for managerial positions and as such end up missing out on these high skilled level jobs. This study aims to evaluate the graduate preparedness for the managerial job; both for traditional degree graduates and apprenticeship degree graduates.

1.3 Research Aim and Objectives

1.3.1 Research Aim

The study aims to evaluate the level of preparedness of degree graduates for managerial positions within companies especially levelling down to the comparison of traditional degree graduates and apprenticeship degree graduates. Achieving this aims calls for an extensive contextual study with regards to the traditional degree job market as well as the Apprenticeship degree job market and equally comparing their characteristics. As such, to be able to effectively achieve the aim of the study, the research was broken down into several specific objectives for direct study including:

1.3.2 Research Objectives

Among the major research objectives include:

To critically review theories and concept related to graduate employability, education levels, and job preparedness

To critically evaluate the link graduate job market and education levels in the UK

To investigate the impact of the Apprenticeship levy to the UK graduate job market

To highlight the differences in preparedness levels for managerial position between Traditional and Apprenticeship graduates

To conduct in-depth appraisal of managerial preparedness by graduate through traditional degree attainment approach vs apprenticeship

1.3.1 Research Questions

What is the composition of the UK graduate job market?

What is the impact of the Apprenticeship levy to the UK graduate job market?

What is the difference in the level of preparedness for managerial position between a traditional and apprenticeship degree graduate?

1.4 Rationale of the study

While the government introduced the Apprenticeship Levy in 2015 to enable graduates a much easier transition into the Job market, Inge (2019) points out that school leavers have experienced a new challenge and dilemma with respect to whether to pursue a traditional degree or a degree apprenticeship. Ideally, apprenticeship degrees afford the graduates adequate experience for the Job market and thus easier entry, the traditional degree still maintain the threshold requirements for most managerial positions in the job market. As a result, the market and education system is on great disconnect with regards to preparing students for the Job market. The outcome of this study will be able to highlight which degree program (Traditional or Apprenticeship) enhances a higher level of preparedness to the graduate with regards to the Job market as well as the managerial position thereby enabling students an easier choice when it comes to choosing their path. The project also illuminates the various strengths and weaknesses of the various degree programs and can influence employer’s recruitment practices and policies. This can eventually smoothen graduates transition process into the job market and development of long lasting careers regardless of the degree program undertaken.

Chapter 2: Literature Review

2.1 Introduction

This literature review will provide a comprehensive understanding of the way different researchers have debated the topic on the preparedness for a managerial role by either a traditional degree or a degree apprenticeship graduate. The upcoming trend that can be observed in many news reports and preferences among household discussions is that more school-leavers are opting for degree apprenticeships, which involves both work and study, over earning a bachelor’s degree alone. Largely, this dichotomy has significant impact on the way people perceive academic and professional development. For example, some may relate the difference between a traditional degree and a degree apprenticeship as making a course application and engaging job competition, respectively. As the discourse concerning the traditional degree and degree apprenticeship has been going on in the public scene, the former and the latter have been pitched against each other. The public consistently compares and contrasts traditional university degrees with degree apprenticeships in terms of the short- and long-term gains (Taylor-Smith et al., 2019; Rowe et al., 2016). While apprentices grant a scholar a head start at work, those who opt for traditional degrees are likely to earn over £500,000 more in the long-run, in terms of wages (Banning-Lover, 2016). Surveys have also linked empowering workforces towards individual and collective potential on career development and self-actualization, as advocated by the apprenticeships, goes a long way in uplifting organization and steering business growth (Dobre, 2013; Ngai et al., 2016). Building on this basis, this research aims to explore gaps in the conversation concerning traditional degrees versus degree apprenticeships influencing graduate preparedness on managerial role as well as responsibilities.

2.2 Theoretical Framework

2.2.1 Human Capital Theory

The Human Capital Theory asserts that investment in human capital leads to greater economic output (Becker, 1994). On the other hand, Mcguinness (2016), in an article that reviewed literature on over-education, assessed the consistency of over-education in the context of theoretical frameworks that included the Human Capital Theory. The paper discussed the different controversies associated with studies of over-education to provide an evaluation of the extent to which the effects of the phenomenon is a reality in economics, contrary to being a statistical artefact. According to Dolton and Silles (2008), over-education describes the degree to which one possesses an educational qualification in excess of the requirement that is necessary for their job. The interest in this phenomenon has grown as economist are trying to evaluate the effects that the continued rapid increase in academic participation rates has become a central feature of labour market policies in most developed countries. Building from McQuaid and Lindsay (2005) assertion on the concept of employability particularly on the emergence of tenet of labour approach towards social and economic policy. According to Tomlinson (2012), the result of the promotion of the concept has reshaped perception on the requirements and qualities for one to be employed or rather the qualities labour market seek in for one to qualify for a given job position. Boden and Nedeva (2010) described employability as ability for one to be employed, retained, and secure new employment if need be by possessing a given set of skills, knowledge, and personal and collective attributes. The Confederation of British Industry (CBI) described employability as “Employability is the possession by an individual of the qualities and competencies required to meet the changing needs of employee and customers and thereby help to realise his or her aspirations and potential in work” (CBI, 1999, p. 1). As contended by McQuaid and Lindsay (2005), although the concept obscure two decades ago, it current commands the labour market and related policy formulation not only in the European but also at global stage. Across the globe, most governments today have a provision that almost 50 percent of people aged under 30 should take advantage of some degree of higher education (Sutherland, 2008; Marginson, 2016; Kucel, 2011). By establishing a reference point or highlighting the ‘required’ level of education for a worker’s occupation or position within an organization, it is possible to decompose an individual’s actual level of education into years of required education and years of over-education or under-education relative to that occupational norm. Over education occurs in the event an individual has more years of knowledge acquired in reference to the required number of years for a position (Dockery and Miller, 2012). After reviewing the literature, Dolton & Silles (2008) and Carroll & Tani (2013) concluded that the effects of over-education are non-trivial and the phenomenon may be costly to firms, individuals, and the economy. It is well established that workers with more years of education earn higher wages. The event of over-education also raises doubts with regards to the validity of some key predictions and presumptions of Human Capital Theory that are not likely to be entirely explained by gaps that exist in the framework of standard wage equation (Ramos et al., 2012; Sicherman, 1991; Bu, and Pollmann‐Schult, 2004). Mcguinness (2016) opines that the policies that aim at expanding the rates of educational participation assume that graduate labour demand increases or hiring of graduates by firms will improve their techniques of production to take advantage of a labour force that is more educated. Verhaest and Van der Velden (2012) concluded that as individuals, workers that are overeducated, by virtue of the fact that some percentage of their investment in education is unproductive, are most likely to earn low return on their investment relative to individuals who are similarly educated and their jobs match their qualifications. Peiró et al. (2010) added that workers who are overeducated might also incur costs that are transitory because of low-level job satisfaction.

It is also possible that workers who were previously well-matched may be driven out of the job market as workers who are overeducated move into occupations that are low-level. This raises the mean educational level within the professions, which renders some individuals who are adequately educated undereducated (Belfield, 2010; Wald, and Fang, 2008). Although some degree of bumping down occurs at educational categories that are higher, nothing suggests that individuals who are at lower spectrum of education had been forced out of the labour market (Leuven, and Oosterbeek, 2011). This is because, according to the human capital theory, apprentices would have to be overpaid to match their worth to employers. For this reason, without subsidies from the government, employers would not participate in apprenticeship programs (Belfield, 2010). However, the Human Capital Theory contradicts views held by Mcguinness (2016) that over-education may lead to low returns on investment in education. Human Capital Theory suggests that society and individuals gain economic values from investment in people (Sweetland, 2016). The human capital theory assumes that education determines the marginal productivity of labour and determines people’s earnings (Marginson, 2017). Human Capital Theory has been dominating economics, public understanding, and policy of the relationship between work and education (Barone, and Ortiz, 2011; Ortiz, and Kucel, 2008.). It is widely presumed that intellectual formation involves an economic capital mode, and that higher education is preparation for work, and that knowledge is what primarily determines the outcomes of graduates and not social background (Marginson, 2017). Building from literature and arguments held by the human capital theory, there is significant evidence that degree apprenticeship does influence the preparedness of graduates for managerial role. The influence can also be said to be much higher and significant for apprenticeship degrees compared to traditional degrees as confirmed by the graduate identity theory.

2.2.2 Graduate identity Theory

The Graduate Identity theory also attempts to answer the question on graduate preparedness and employability. Holmes (2001) explored the graduate identity idea with his starting point in graduate identity was rooted on the lack of satisfaction with the idea of graduate employability in terms of acquisition of skills. According to Holmes (2001), the skills approach does not take into consideration the complexity of being a graduate because of the presumption that skills and performance must be observable and measurable. Hinchliffe and Jolly (2010 suggest that performance depends on interpretation of a situation but the ability to interpret is not measurable in a straightforward sense. Interpretation is also complex itself and depends on both understanding of a situation with regards to practice and understanding agents with regards to their identity in the context of practice. Therefore, the identity theory suggests that graduates do not have single fixed identity (Hogg, and Adelman, 2013; Tomlinson, 2012). Building from the argument, when evaluating graduates’ potential, employers use other criteria other than performance and, thus, it is difficult to conclude whether a apprenticeship degree prepares one better for a managerial role compared to traditional graduate degree. Although the UK is urging higher education students to view their studies as an investment that will benefit them directly, the relationship between the academic credential and their returns in the job market has been changing at the same time over the past decades (Leuven, and Oosterbeek, 2011; Stuart et al., 2014). Tomlinson (2008), in a qualitative study examining ways in which 53 final year undergraduate students in a pre-1992 perceived and understood role of higher education academic credentials with regards to their employability in future. The study showed that higher education students view their academic qualifications as having a purpose that is declining in determining their employment outcomes. They perceive graduate job market as congested. As such, while students still understand academic credentials as still significant in determining their employability, they increasingly see the need to add value to academic qualifications to gain an edge in the job market.

2.3 The Apprenticeship Levy

Apprenticeships, a concept build around combining job tasks and training, play a crucial role in ensuring that people develop skills that society and the economy need. Each apprenticeship has content that may be set out in ‘standard’ or ‘framework.’ However, frameworks decreasing being used as standards take over as standards are designed by employers in the sector to determine the skills, behaviours, and knowledge that apprentices are needed to acquire (Wolter, and Ryan, 2011). Over 300 of possible 600 standards had been approved by 2018 (Behringer, 2017). Further, studying the overall aims of the apprenticeship levy, (Amin-Smith & Sibieta, 2018) looked into the levies aims, such as to increase total training of the workforce, and to assist in funding the three million apprenticeship starts from the government. While the objectives of the apprenticeship levy are clear, it is crucial to correct for underinvestment in training of the workforce, and people need to understand how employers react to the introduction of the levy. According to Brewer (2013), apprenticeships have been proven to result in benefits for employers, apprentices, and the economy. However, as mentioned before, there is a significant issue of how to stimulate employers to demand apprenticeship training and to get them to invest in this form of exercise. To consider how far the levy will go in overcoming the problem, it is essential first to have an understanding of the factors that can facilitate employers to invest and the factors that are likely to create obstacles to employers' training and giving apprentices job opportunities (Bailey, 2010; Steedman, 2012). According to Behringer (2017), about 24 percent of employers that are not already taking part in apprenticeships indicated that they are planning to provide them in future. Eighty eight percent of employers who are already engaging in apprenticeship plan to continue providing apprenticeships (Behringer, 2017). This percentage represents about a third of all employers in the UK that plan to offer apprenticeships. However, this figure has not materialised fully in employers’ uptake of apprenticeship. The results also indicate that some of the reasons that employers give for not providing apprenticeships are mostly structural. The reasons include capacity to train and take on apprentices and cost considerations. Furthermore, employers refuse to take on apprentices as they do not need specific skills among their employees or they prefer recruiting skilled workers who are ready from the labour market. More employers do not offer apprenticeships because of different kinds of market failure, and a lack of knowledge regarding the benefits of apprenticeship might bring to a firm or the net cost the business will incur in training apprentices (Lee, 2012; Albanese et al., 2017). Other employers are also risk-averse. In a labour market like the UK that is buoyant and flexible, an employer may not be sure about appropriation of the returns from investments in apprenticeships. Unless employers have practices and policies in place to ensure that they retain their apprentices once training is complete, they will be risking losing their apprentices. For this reason, as pointed by Muehlemann & Wolter (2011) and Lewis et al. (2008), they will be investing in training employees for their competitors. As such, one question that should be asked is whether apprenticeship will be relevant in the future. Smith (2019) writes that changes are rapidly occurring to occupations and will continue happening because of advanced technology. Companies are also increasingly operating globally. Schmid (2008) and Blossfeld (2008) opine that there has been a change in the labour market in terms of employment in many countries, from manufacturing and primary industry to service industries. Further, patterns of migration and non-standard forms of employment, such as the ‘gig economy’ are affecting many workers (Wood et al., 2019; Oliver, 2015). In addition, other changes are affecting the future of employment. Smith (2019) states that since apprenticeships involve training and employment of workers and generally involve oversight and management by governments, they will probably be affected more by the challenges of future jobs than other forms of training or employment. This implies that apprenticeships will continue to be an arena for policies of governments including regulations and the shaping of the behaviour of funding (Brockmann et al., 2010; Chankseliani et al. (2017). Hodgson et al. (2017) adds that there has been minimal action regarding apprenticeship systems even though could be disruptive to networks that exist now.

Smith (2019) found that stakeholders such as employer peak bodies and trade unions at company level were pursuing processes and systems adaptations at the company. However, these adaptations were not frequent in government policies. The study by Greene & Staff (2012) and Bai et al. (2012) analysed data to come up with a model of readiness for future work. The study also asked questions about whether adapting systems of apprenticeship is desirable in every instance. Smith (2019) posits that although multiple stakeholders being present in the order have been seen as a strength, it can make even changes that are minor challenging to implement. Fuller and Unwin (2014) also warns that this could be a significant obstacle to the future of apprenticeship or could be a way of preserving the features of apprenticeship that are essential. However, Heyes & Hastings (2017) and Suarta et al. (2017) suggests that the recent changes in the job market and economy, and their accompanying effects on jobs in future, could radically disrupt systems of apprenticeship globally, and make them less relevant or irrelevant in the 21st century.

2.4 Degree versus Degree Apprenticeship

Degree and Higher Level Apprenticeships were introduced in 2014 aimed at increasing the apprenticeship graduates to over 3 million by 2020 to provide an alternative route to professionalism and creating equality and parity of opportunity for people choosing to undertake an undergraduate or postgraduate program through a way that is not conventional (Rowe et al., 2017; Irons, 2017). The aim of the study by Mulkeen et al. (2017) was to explore the opportunities and challenges of delivering and designing Degree and Higher Level Apprenticeships at levels 4 to 7 from a perspective of multi-stakeholder such as universities, employers, professional bodies, and organisations that provide independent training. Respondents in the study highlighted different factors that relate to the graduate opportunities of apprentices in comparison to other graduates. The elements were categorised into parity of opportunity and equality of esteem. Respondents saw the management of the perception of stakeholders as being crucial to the success of Degree and High-Level Apprenticeships in comparison to conventional degree programs (Mulkeen et al., 2017). This included managing the perceptions of the knowledge and skills of people that achieve their degrees through apprenticeship in comparison to those studying though the conventional routes, career opportunities, the abilities of different graduates, and the value that is placed on each qualification. Traditional degree programs have already established a reputation with students, parents, and employers while apprenticeships are always associated with occupations that are vocational or require technical skills (Rowe et al., 2016; Bishop, and Hordern, 2017). Mulkeen et al. (2017) posit that in order to change perceptions, it will be necessary to educate stakeholders on the benefits of achieving qualifications through apprenticeships. Apart from parity of esteem, respondents of the study by Lambert (2016) highlighted the parity of opportunity for apprenticeship students in comparison to students who achieve degree through a conventional route. Although parity of opportunity has no definition that is universally accepted, some of the themes that were most raised by study participants included parity while at university and parity of opportunity when they graduate. Baker (2018) also echoes Mulkeen et al. (2017) that the perceptions of employers regarding degree apprenticeships are negative. Employers also associate apprenticeships with ‘trades’ and manual labour. Marx et al. (2015) also suggested that apprenticeships in NHS and registrants who completed more conventional preregistration programs would be more likely to progress to roles that are more advanced in comparison to vocational learners. Further, Ainley and Rainbird (2014) describes the split between apprenticeship and tradition learning as privileging of academic qualifications over the qualifications attained in workplace learning. The perception that apprenticeships appeal to people who have achieved lower levels of education also leads to confusion about the value of degree apprenticeships (Chan, 2013; Ainley, and Rainbird, 2014). Baker (2018) also suggested that there is poor understanding of apprenticeships be career advisors, employers, and potential apprentices, which contribute to negative perceptions about the value of apprenticeship. This negative perception is reinforced further by Ryan & Lorinc (2018), who note that the misconception that apprenticeships are ‘second class’ and that recognition of degree apprenticeships need to improve. Therefore, if perception about degree apprenticeships change, degree apprenticeship graduates will be regarded as equally capable of taking up managerial roles.

2.5 Undergraduate Education and management Roles

Proponents of promoting education levels and management roles view the approach as one of the most critical elements of employer-employee relations (Baugher et al., 2014; Belfield, 2010). As far as an employee is concerned, a promotion to a managerial role is not just a reward and expression of gratitude by the employer, but also an opportunity for career advancement and self-fulfilment, satisfying their need for success and accomplishment (Pillai et al., 2012; Gul et al., 2012). For this reason, it is vital to know what determines how a manager performs on the job. According to Muda (2014), how effectively managers perform cannot be predicted by the number of degrees they hold, the grades they receive in school or the formal programs of management education they attend. Education, incorporating structured learning system or through day-to-day challenges and combating changes encounter as well as experiences, play a fundamental role to success with survey associating high quality formal education with greater wealth, health, earning, and lifestyle. Nevertheless, as pointed by Pinto and Ramalheira (2017), academic achievement cannot be a reliable yardstick for measuring potential of people in management roles making apprenticeship degrees more effective for preparation of managerial positions due to the education and experience earned. Nguyen & Hansen (2016) state that even though all formal management education has the implicit objective to help managers learn from their experiences, most formal management education is miseducation because it distorts and arrests the capability of managerial aspirants to grow as they acquire knowledge. Therefore, first learners in the classroom are often not always good managers (Muda, 2014). On the contrary, Dike et al. (2015) assert that promotions to managerial positions are based on the abilities and efforts of individuals. Dike et al. (2015) add that managers are promoted based on their skills and initiatives according to the rations' point of view. The presumption is that individual qualities can be used to objectively measure people’s abilities (Truxillo et al., 2012; Danish, and Usman, 2010.). The person best suited for a managerial position is one whose attributes best suit the position. Organisations also support this perspective through processes of reward and appraisal, which offer incentives for additional education, training, and individual achievements. Although, organisations may prefer people with additional training to take up managerial roles, academic level has little correlation to managerial performance. Therefore, whether one achieved their qualifications through degree apprenticeship or traditional degree does not determine whether they would be a perfect fit for a managerial role.

2.6 Summary

While both traditional degrees and apprenticeship degrees offer effective education and preparation of individuals for the job market and different roles and positions, the experience attributed to the ‘learn and Work’ relationship in Apprenticeship degrees guarantees increased skills and abilities for apprenticeship degree graduates as compared to traditional degree graduates. While traditional degrees are associated with eventual higher pays and earnings than apprenticeship degrees, the skills and experiences gained by apprenticeship degree students within the process of their education and learning significantly gives them a head start in the actual conditions within the market. This enables the acquisition of necessary hands-on and decision making skills that eventually make them much more prepared than traditional degree graduates in relation to managerial roles.

Chapter 3: Research Methodology

3.0 Introduction

According to Ochsner, Hug and Daniel (2012), the purpose of a research study, especially one that takes into account primary study is to enable the development of new knowledge as well as introduce new perspectives of thinking and reflecting on issues, this is attained through adoption of a systematic development methods. As pointed by Kumar (2005), research methodology includes the description of the different methods to be utilized in the conduction of the actual study process in order to be able to derive inferable findings. Based on the content analysis of literature by different authors presented in the previous chapter, this chapter contain a discussion of the research design and philosophy as well as the area of the study, population of the study and sampling techniques adopted towards the realisation of the research aim addressing graduate preparedness to managerial roles in the UK taking the perspective of both traditional and apprenticeship.

3.1 Research Design

A research design dictates the direction of the study as well as the manner by which the research is conducted. According to Saunders et al. (2009) and Remenyi et al. (2003) a suitable research design needs to be selected based on research questions and objectives, existing knowledge on the subject area to be researched, the amount of resources, time available as well as the philosophical leanings of the researcher.

For this study however, guided by the above principles the researcher adopted a cross sectional, mono method survey as the research design and use of interviews. Griffiths, (2009) points out that the qualitative research design involves detailed exploration and analysis of particular themes and concerns within a topic, for instance, underlying concepts of employability and graduates’ preparedness for a particularly role. Further, the approach highlighted that qualitative approaches are particularly useful when the topic of research is complex, novel or under-researched as it leaves the results open to the possibility of unexpected findings, rather than predicting an expected outcome as is often the case for quantitative research.

3.2 Philosophical paradigm

Based on the provision of the Research Onion Diagram (Saunders et al., 2007) as shown in Figure 2, this study adopted a qualitative and inductive research design, premised on an interpretivist philosophy that treats the world as a conglomeration of social constructions and meanings in human engagements and lived experiences (Daymon & Holloway, 2002; Gomm, 2008). Building from the interpretivist paradigm that works in dichotomy with the positivist model viewing the world as an embodiment of clarity, unambiguity, and verifiable reality that can be studied only with total objectivity (Cavana et al., 2001), within this research, it was held that the purview of employability as well as preparedness is a multifaceted and subject to social, workplace, and economic beliefs and demands of employee’s attributes. As such, it combined the rationalist and empiricist approaches and encapsulates concepts, theories, frameworks, and case studies in explicating the different research concerns, including objectives, questions, phenomena, and behaviours on employability and job preparedness (Abend, 2008; Swanson, 2013: Weick, 2014).

3.3 Research Approach

Research methods describe the procedures that were involved in the data collection process, analysing, and ultimately interpreting the findings while aligning the process with aim and problem posed by the research. Ideally, in order to develop evidence-based inferences while at the same time addressing the research problem in a concise and adequate manner, a systematic process is needed build around beliefs held and stepwise. Literature exist pointed to the role played by employees’ confidence build around experience as well as importance of attributes in meeting job requirements coupled with positive and drawbacks of both traditional training and skills acquisition compared to the apprenticeship approach. In both approaches, the focus has been fundamentally building workforce that addresses extensively the job requirements and best fit in terms of qualification that include personal attributes and acquired skills of employees to the job. Based on this and in order to meet the research aim, the methods adopted were inductive and qualitative reasoning built around understanding underlying concepts and factors (Silverman, 2016; Marshall, and Rossman, 2014). The research involved a primary data collection method which involves the use of interviews.

3.3.1 Interviews

The main advantage of interviews stems from their capability to offer a complete description and analysis of a research subject, without limiting the scope of the research and the nature of participant's responses while fundamentally capturing the insight of the research problem (Collis & Hussey, 2003). The researcher conducted an interview to be able to find much deeper and personal insights of the respondents’ relation to the topic of study. Specifically the interview conducted was semi structured implying that follow up questions could be asked to further clarify the answers of the main drafted questions for the interview. For instance, some response given by the participants warranted an explanation and the interviewee would just ask the respective participant to elaborate further. Hence, allowing delving deeper into the response given. This is especially important to be able to receive explanations on their perceptions of the graduate job market as well as the qualification and preparation levels necessary for managerial position. The questions were designed to highlight individual respondents views with regards to what the job market entails for different graduates; how easy is it to secure employment and grow in a career to managerial levels for the two different types of graduates as well as whether that impacted their choice or not while pitting traditional against apprenticeship degree approaches. Further, concerning the various perceived skills and qualities of managers, the interviews seek to understand from the respondents, the level of preparedness of the different graduates for the said managerial positions.

3.4 Target Population

Gobo (2011) defines research population as a group of people, subjects, objects, and/or item that impact an element of the study being taken up and as such, are of interest to the research process. With regards to the aim of this research and considering the objectives and the nature of the information needed, the research specifically focused on university students under traditional degree students as well as Apprenticeship degree programs.

3.5 Sampling

Onwuegbuzie and Leech (2007) described research sampling as a parameter that enables researchers to select a suitable group of individuals or items from the population for data collection and analysis, consequently as such, influencing the overall research results. The most basic sampling methods entail either probability or random sampling, which gives equal opportunity for selection to the entire sample population; as opposed to non-probability or non-random sampling, which requires a specific rationale for the inclusion or exclusion of sample groups of a population. Knowledge of the range of one’s population and its composition is integral in the determination of whether probability sampling can be implemented (Blaikie, 2010). In

This study employed the use of the Opportunity probability sampling technique given the scarcity and inaccessibility of the study population. The researcher used referrals from the key contacts to assemble a group of 8 key participants of the research. The sample was also carefully selected from different universities and institutions involved in Apprenticeship. However, it ensured that both degree, traditional and apprenticeship programs were covered.

3.6 Data Analysis

Thematic analysis is the main tool for analysis for the primary data collected through the questionnaires issued to respondents. According to Braun and Clarke (2006), thematic analysis is a qualitative research method of analysis that takes into account the identification, analysing and reporting of patterns, themes, and connections available within raw data. Through the use of the data collected through a wide variety of different research methods such as interviews and/or questionnaires as applied in this research study, accurate and replicable inferences can be made from the analysis of the various patterns and themes to further explore the level of preparedness of traditional degree as well as apprenticeship degree graduates for the job market and managerial positions. The evaluation of the different interviews in the primary study was conducted through an iterative coding process that enables the identification of different patterns and themes from different interviews conducted. Different themes as well as other unusual and unexpected ideas were noted from the transcribed data of the five interviews after which they are grouped into major themes related to answering the research questions and objectives. These themes are then supported with identified sub themes, which are supported in the report by direct quotes from the respondents of the interview. Building up on these themes, the researcher then switches from empirical observation and analysis to conceptual analysis where the findings are related with other findings from the literature review to provide inferences, which are the answers to the research questions and solution to the entire study. This process is referred to as the interpretation of the data and can be descriptive, interpretive, or analytic depending on the data type collected and the types of study being taken up.

3.7 Ethical Considerations

The research involves the collection of primary data that involves human interaction and the use of humans as the major information source, ethical considerations in terms of relevant courtesy to be afforded the various individuals while collecting this information as outlined by British Psychological Association (2013) is therefore a major concern. To avoid ethical issue therefore the researcher will secure an advanced permit from each respondent identify to interview them. Also the study will focus on interviewing only willing participants and further keeping their names and identity anonymous so as to enhance their privacy. In addition to upholding the privacy and confidentiality of the participants, this research ensured the academic integrity and validity is emphasized and maintained by ensuring information used within the research is cited accordingly.

Chapter 4: Findings

4.1 Introduction

This chapter presents the findings of the research outlining level of graduate preparedness for a managerial role measured through either traditional or apprenticeship approaches. The data collection involved interviewing eight students under either traditional or apprenticeship university degree programs graduates seeking to highlight their perspective of the graduate job market, highlight the impact of the apprenticeship degree programs, and evaluate their readiness for managerial positions. The questions of the interview (Appendix table 1) were pre-formulated to capture the graduate preparedness, views on job market, and job requirements grounded on person perspective and experiences from learning format. However, as noted before, the interviewer modified the questioning based on the response given by the participant. The data was evaluated and analysis using thematic analysis that allows the derivation of themes patterns and relationship between first and data collected through various techniques as interviews. This chapter capture the data collected, themes development process, and analysis of the findings. The data from interviewed were recorded using voice recorder then transcribed into text before coding the findings.

4.2 Respondents Background

The researcher interviewed eight students from different Universities including traditional degree universities such Greenwich University as well as Apprenticeship institutions such as the navy. Four of the eight respondents are studying through Apprenticeship degrees. These include Navy engineering, Theme portfolio management, and a family business. The remaining four were studying traditional degrees in business management with business ideas of their own brewing on the side. The participants were in their third and final years within the university thereby providing the most effective response group for the impact of apprenticeship degrees in the job market. In adherence to ethical considerations, the names of the participants are withheld but represented in code names such P1, P2, P2,.. etc. representing participant 1, participant 2, and so on respectively.

4.3 Study Findings and Analysis

Response Coding

The coding process adopted involved searching and picking key and expressive words and phrases used by participants such as ‘experiences’ and ‘opportunities’ perceived to relate to such factors as skills, knowledge, and attributes needed in larger job markets. The identified coded words and phrases from the different participants were then grouped to identify themes and relationship between them and participants group. Notably, the participants were grouped to either traditional graduate (those in traditional degrees program) or apprenticeship students (those in apprenticeship degree program)

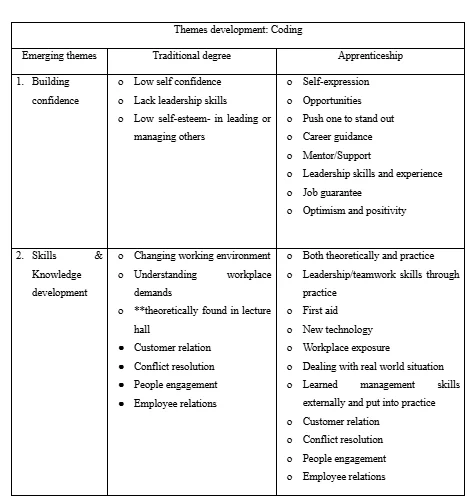

From Table 4.1 above, the participants’ responses was code in 11 emerging themes building around factors considered by participant core in managerial role. Notably, all the emerging themes and code are picked from the responses of the participant, and not picked directly from the transcribed responses. Moreover, the emerging themes are captured within either traditional or apprenticeship column to represent accordingly the participant under respective program. However, building down from the study objectives, the dissertation classified the data into five themes through coding the participants’ responses.

Themes

4.3.1 The Graduate Job Market

All the respondents irrespective of the degree approach acknowledged that the graduate Job market is more inclined to look for experience rather than effective education qualifications. The eight respondents admitted to significantly thinking about their future after completing their secondary school before committing to the different degrees that they are currently involved in.. Participant 3, P3, noted that;

“I did consider umm I did consider starting my own business or just working in general… I wanted to umm run my own eye lash business but I felt like umm if I didn’t do a degree umm after a levels umm.. I feel like it would have been a waste of my time …do the business alongside my university degree if I wasn’t gonna start my own business then I would have considered working so my family runs a restaurant business and I help out there part time anyways but I would have decided to work there after...”

Similarly, irrespective of career and degree approach, participants reasoned heightening competition in the job market caused by several factors ranging from globalisation, labour demands, rising unemployment, and supply of workforce. UK market in very competitive, globalisation has lead graduate to compete with not just those within the UK but other country for the same job. Participants held that such intensive competition has demanded one to stand out by having skills and experience core to job requirement. P2 stated

“…also going to be loads of other students that will have the same qualification as me looking for a job. So I feel like the skills really help you like stand out…”

4.3.2: Role of university education

According to P1, in university, one meets people from different, and various background ranging from culture, social, beliefs, religious to political who challenges one thinking and point of view, which can be incremental in development and growth.

“…university isn't only about the educational side of things which boy wants, but it was more about the experience and the network…”

Additionally, according to P2, university are fundamental for managers and individual in leadership roles, as well as giving students a platform of understanding others and people around them

“…to know the context and get to know the people around you to understand how to be a manager. It's not just applying the skills you need to have like, you need to get to know the people around as well to manage them…” ,

More so, according to participants, traditional university programs gives student a platform to gain theoretical knowledge on relationship of various management components, however, practical exposure give a worldview of issues. According to P5,

“…university helps you prepare yourself to be a manager in a different type of environment or any type of environment, not just restaurant in terms of life is let's say you work in an office as a manager…”

While the two respondents taking up traditional business degrees have family business, they still choose to pursue the degrees in order to influence their knowledge and enhance their skill levels to further build their family businesses and even engage in start-up of their own business ideas or enhance their employability levels.

Nevertheless, some participants view university as an avenue to prepare graduate theoretically to job market giving qualification but not adequate preparation arguing that it just doing theoretical concepts and exams with little exposure or doing practical aspect of the course.

According to P3;

“…I personally believe that the universities are just a way of getting qualification. There's not there's no really there's no, there's not much experience behind it…”

While P7 stated;

“…the main reason why I chose to do a degree is because I feel like …, it's quite normal to have a degree. …but it's very common. Have a degree and I feel like when you're competing with other people, if you don't have a degree, it's kind of harder to compare...”

However, P5 indicated the skills learned in classroom were lacking prompting other means such as YouTube videos, tutorials, and online libraries to learn and put into practice management skills and knowledge. Stating

“…under a lot of YouTube videos, tutorials, and just to help myself, obviously, I've learned a few things from university lectures, and on just how to manage people. One subject will be a management in context. And that helped me understand how to manage people in different situations from different cultures for and as well as international business, how to deal with people from different countries, and different ethnicities and stuff like that…”

The three respondents under apprenticeship degrees pointed out that significant knowledge learnt in a class setting impact their overall understanding and performance in the field that in turn influences their experiences.

4.3.3: Preparation for job market requirement

Six of the eight interviewed participants held a view that having a degree only would not make one to standing out despite making her/him being employable. According to P2, the only differentiating factor is exposure and work experience, stating

"…I feel like my degree personally, will definitely help my employability. But it also depends on the skills and the experience that I have as well…”

Some perceived formal university education acts as a backbone that make one to be considered for the role but experience and exposure set them apart from the group

“It's not just your degree that will help you because just having a degree doesn't mean you have the relevant skills or you have the relevant like mindset…”

For instance, according to P5, managing people dealing with conflict management and relating with individual from different backgrounds demands more than theoretical but rather engaging directly with them. People have different personality, behaviour, and viewpoints, which can be hard to explore and comprehend extensive in a classroom setting only.

P5 noted;

“…within a restaurant, you're dealing with people from all over the world. There's different ethnicities, different cultures, different backgrounds, and how to communicate effectively...”

Those participants interviewed taking the apprenticeship route argued, held conviction that juggling class work and practical aspect of concepts talk is a refreshing removing boredom normally experienced in class in addition to allowing graduate to draw career road map coupled with professional guidance and supportive mentors. According to P3, combining classwork with practical aspects push for stand out individuals to self-express and be confident

P3 held that

“...I get to work hands on with the aircraft. I don't I know,... I get to actually pick up the metal pieces I get to weld, I get to do so many different things, and it's much better than the university route...”

Moreover, those in apprenticeship indicated having first-hand experience in leadership “…in situations where I've led the team in certain scenarios…” and mentorship and guidance from a person with experience in the field a confidence and draws what need to be done to attain career requirements.

According to P3,

“…I have a degree of mentors, I'm essentially ahead of people..”

Whereas asking similar question on career development plans and entry in job market to traditional-oriented students, response show they regard them at a lower par, not at the same level with their counterpart in apprenticeship programs. The difference being experience.

P3 argued

“…We are learning the same things in the first year is just on top on additional things I'm learning the things in the workshop… certain qualifications that can only be gained for the apprenticeship, I have a major advantage compared to them because as certain companies would prefer someone in the whole engineering world is based on experience…”

On the other hand, P1, a traditional degree student but worked as manager in family-owned restaurant as a part-timer, argued that experience goes a long way in building confidence stating;

“Number one thing is confidence. You know, you may have all the knowledge in the world, but if you can't reiterate it, or if you can present yourself in such a way that why would people not have your job? Why would people want to listen to what you have to say? So having confidence is a massive thing that …”

4.3.4: Employability

All participants agreed that heightening competition has changed the requirement where employees nowadays look for experiences and exposure rather than academic qualification. Across the eight interview participants, those under apprenticeship and participant in traditional degree model but working part time demonstrate keen awareness on job requirements, demands, perspective, and attitude attributable to the exposure and experience drawn from respective work. All held that combination of class work, theoretical aspect of learning and practical giving learners work experiences is important and one should be able to integrate the two- vertical learning enhances personal and professional experiences. Participant P1 and P3, contended that combining work and classwork set the student practise concepts and skills learnt resulting in more confident and exposure compared to traditional class work only approach- traditional degree give little opportunities for experience development such as conflict handling and management.

P1 stated;

“…Yeah, a lot of 20 year olds out there right now are very different to the way I am, I suppose, you know, I've always pushed myself above above the obvious. I didn't sit there and accept what had up who is pushed myself, despite being manager of model space…”

P3 point out;

“Many different companies, especially defence companies value someone who's been a veteran in the UK military as they know that they have been trained vigorously. And I've been through different experiences, which give them lots of qualifications and experience. So I chose this one, because I know that I've always wanted to be an engineer.”

In addition to training and theoretical learning, those in apprenticeship program gain first-hand experience by working, for some in big organizations.

P5 stating:

“…a lot of my peers and my friends actually went into apprenticeships in companies such as BT wireless group, recruitment agencies, and now after discussing it with them, …they got good secure jobs, and they also are getting training.... work experience…benefit all students as that will give them the experience that many employers look for…”

Student in traditional degree pointed lack of experience as hindrance to employment such that they lack connection with the real world situation. Most noted that class work and workplace learning is different and that missing linked of putting learnt class aspects into workplace set them at a disadvantage.

P5 on experience compared those in apprenticeship program, stating

“...I haven't really picked up all the practical skills required.., I do have friends that have done similar course but as an apprenticeship where they work in while learning and this provides a practical element to the overall learning objective. And this means they have the skills that I don't…”

P6 stating

“….maybe if I had done an apprenticeship, I wouldn't need to develop on these. I would have the practical skills required for the job…”

Whereas P2 noted;

“…for my experience, I haven't dealt with any type of conflict in the workplace, because we're, we're quite a small business. And I feel like I wouldn't really know how to handle conflict if being a manager or my, the people below me didn't work well together or, or there was conflict, then I wouldn't really know what to do. So I think Feel like that comes with experience..”

4.3.5: Level of Preparedness for Managerial Role

Collectively, all participant agreed on requirement and skills set need to be an effective manager. However, responses by apprenticeship students show a clear pattern of understanding key factor such as values of an effective manager, and leader. From data, apprenticeship student demonstrated inner working of workplace that include the demands of workplace, organization culture, interpersonal relationship, and communications skills such as having hand on experience in leadership, importance of communication, time management, teamwork, leading a team, conflict resolution, interpersonal relationship, dealing with different individuals

Leadership

P3 stated

“…in situations where I've led the team in certain scenarios…”

Decision-making

P1

“…decide on different tasks and uh what to do and I feel like that also applies to my job as well so I have to make loads of decisions really quickly because I’m always face to face with the customer so I feel like that will help..”

P7

“…I've improved by writing down all the dates, and deciding when to do the work and just all going to be more organised as well. So being more organised has helped my time management…”

Motivation

P3: “…motivate a group to work harder, is it all ties in together and it's given me a lot of confidence, it's given me a lot of positivity, that I can do anything I set out to achieve…”

Demanding work and time management

Stressful: Limited time for learning and preparation (though one gets experience in combining class work then transferring learnt concepts and ideas to real world scenarios, the stress of combining class work and work demands is a times overwhelming. P6 noting that

“….put you in that mindset, oh no go work tomorrow. And especially when it's down to assignments time, it does get stressful because you're worrying about assignments you're worrying about leading from the front at work..”

On the other hand, traditional degree students have skills and conceptual knowledge but lack confidences and exposure. Additionally, participants under apprenticeship showed a lot of low self-esteem and lack of confidence

P5 noting;

“…I don't know if I feel like I've done enough leadership in in my degree or in my, in my work experience to be a really good manager…”

Other recurring sub-themes

Career path

Participant under apprenticeship program showed positivity, optimism concerning their respective future argues that in addition to experience, and exposure, the career path in nearly guarantee.

P3 noted

“...I'm guaranteed a job there. And it's just it's given me a lot of optimism and positivity in the future what I can achieve what what is possible…”

Contrarily, participants pursuing degree under traditional programs had reservation on their careers.

Chapter 5: Discussion

This research investigated the composition of the graduate job market focusing particularly in the UK. The literature and the findings indicate rising arguments that employers are increasingly moving away from one’s academic qualifications informed most by theoretical knowledge during employment rather checking attributes, skills, and experiences. While experience is significant in being able to secure a job and thus swaying most students to consider apprenticeship degree programs, regardless of the amount of experience one has without a traditional degree on that respective discipline then their chances for landing managerial positions are limited. According to Rowe et al. (2016) and Bishop & Hordern (2017), traditional degree programs have already established a reputation with students, parents, and employers while apprenticeships are always associated with occupations that are vocational or require technical skills thereby reserved for the low level employment positions. This is also confirmed by the general preference of higher learning students taking up apprenticeship programs over traditional degree programs. Graduates are more interested in adding experience into their curriculum Vitae with, high hopes of eventually landing jobs because of it. Increasingly, managers in specific industries such as the military and navy are considering experience even in management jobs and as such influencing the preference of apprenticeship over traditional degrees. This confirms that the graduate job market is significantly in transition and employers and graduates alike are not in tandem with the necessary requirements and considerations for the job market. This consistently relates to the studies by (Brown, 2016; Tomlinson, 2008; Leuven, and Oosterbeek, 2011; Stuart et al., 2014) who are in agreement that higher education students view their academic qualifications as having a purpose that is declining in determining their employment outcomes. They perceive graduate job market as congested. While students still understand academic credentials as still significant in determining their employability, they increasingly see the need to add value to academic qualifications to gain an edge in the job market. Mulkeen et al. (2017) posit that in order to change perceptions, it will be necessary to educate stakeholders on the benefits of achieving qualifications through apprenticeships. This is because while priority is given to traditional degrees by all the stakeholders while Apprenticeship degrees are actually producing much better employees whose are more effective and efficient and thus more prepared and qualified for managerial positions. All the eight respondents confirm their preference of Apprenticeship due to the hands on skills and experience that comes with it which is currently a key requirement in the job market. On issues of influence of apprenticeship programme on the UK graduate job market, the finding indicates a significant correlation. The introduction of Apprenticeship levy in the 2015 brings with it significant changes in career and education perspectives as well as the graduate job market. In the backdrop of difficulty in transition for graduates from school to the job market due to the disconnect between the theoretical concepts and concepts of learning institutions and the practical characteristics of the job market which requires experience, the UK government developed the Apprenticeship levy to bridge this gap. Apprenticeship degree programs offer experience training alongside theoretical learning in classrooms thereby enabling the graduate both educational qualifications as well as intended experience. This program has had an impact both in the graduate Job market through altering employers and graduates perspective concerning the requirements and qualifications for the job market. From the Table 4.1, all the respondents confirmed the significance of the knowledge learned in class during the apprenticeship programs as well as in the traditional degree. However, participants under apprenticeship degree programs showed higher prevalence of such attributes as confidence, experience, leadership skills, and workplace exposures compared to traditional approach. According to literature, education is more than obtaining degree but building oneself both psychologically and socially through establishing lasting friendship while at the same time opening mind and exposure to different culture and socioeconomic backgrounds. This highlights a preference on gaining experience alongside educational qualifications given its importance in the Job market as highlighted by (Hogg, and Adelman, 2013; Tomlinson, 2012) all of who highlights that the employers in the UK despite not entirely depending on qualifications and performance, put a significant weight on experience in a certain position before employment.

Lastly, the research question focused level of preparedness for managerial position by both traditional and apprenticeship degree programs. Five of eight respondents interviewed admitted to significantly considering the option between Traditional Degrees and Apprenticeship programs because of securing experience or a position in the graduate job market. Given that Apprenticeship offers effective experience required for the job market, and an increasing requirement by employers for effective experience on a respective position, students have the perspective that apprenticeship degree graduates are much more likely to secure jobs upon graduation compared to traditional degree graduates. This highlights a significant impact of the Apprenticeship levy to the job market through employers as well as graduates and is consistent with studies according to (Lee, 2012; Albanese et al., 2017) who point out the increased preference for apprenticeship graduates with experience for employment positions in the UK compared to traditional graduates. They highlights that the possibility of enhancing student experience and knowledge at the same time in the process of learning increases the capabilities and effectiveness of the employee thereby making them more fit for work than individuals with no experience. This point out that graduates with apprenticeship degrees are much more prepared and qualified for management jobs given the significant and necessary requirements for management of businesses in the current shifting business industry. Smith (2019) writes that changes are rapidly occurring to occupations and will continue happening because of advanced technology. Companies are also increasingly operating globally. Schmid (2008) and Blossfeld (2008) confirm that that there has been a change in the labour market in terms of employment in many countries, from manufacturing and primary industry to service industries. Further, patterns of migration and non-standard forms of employment, such as the ‘gig economy’ are affecting many workers (Wood et al., 2019; Oliver, 2015). All this are complicating the management field and certainly knocked it of the curriculum context. As such, first-hand experience and skills are necessary for an effective level of preparedness for graduates. Most individual as such engage in persuasion of traditional degrees while at the same time engaging in Apprenticeship to impact their level of tangible and applicable experience and preparedness as well as qualification for managerial jobs in the job market.

Chapter 6: Conclusion and Recommendation

6.1 Conclusion

The findings of the study points out an inherent change in the graduate job market as a result of the introduction of the Apprenticeship levy program in 2015 by the UK government. Given the increased dynamic nature of the graduate job market due to globalization and frequently shifting technology, traditional degree curriculum falls short of the necessary experience required for the job market. As a result, while employees are looking for graduates with experience, only apprenticeship programs offer the necessary and required job experience to enhance employability upon graduation. Most students are as such resolving to taking up entrepreneurship other than traditional degrees with the aim of gaining enough experience for the job market. This qualitative research adopted semi-structure interview in data collection in investigating the level of graduate preparedness towards managerial role by examining students under traditional and apprenticeship degree approach. The findings showed that apprenticeship has led to the increase in the skill levels and capacity of individuals who prefer it to traditional degrees. While all the respondents agree to the effective need of the traditional degree qualification especially in enabling development of a progressive career, they also point out that the practical work carried out within these Apprenticeship programs in the navy or with the family business significantly impart essential skills of management which have an overall effect of increasing the level of efficiency of the graduate job market. Apprenticeship programs significantly lead to the enhancement of graduate skills and abilities as well as experience which eventually impact the entire UK workforce. However, given the complacent state of the job market which still relies on traditional degree qualification for managerial positions, the attainment of traditional degrees is still perceived as quite significant both by the employer as well as the graduate students. While apprenticeship degree graduates are not sufficiently qualified for managerial positions they are well prepared for the position on the other hand traditional degree graduates are not sufficiently prepared for managerial position yet sufficiently qualified. This presents a dilemma in the job market for all stakeholders leading to students opting to pursue both in the end. While participant recognize the need for educational qualifications through traditional degrees, experience is increasingly becoming a more important requirement not only for employability but also for being able to manage businesses and start-ups. As such, the job market is not significantly precise on whether education qualifications or experience is the most significant. Apprenticeship programs however due to their capability of offering both education and experience are the most preferred career paths currently and highlights among the impacts of the introduction of apprenticeship degree programs. The ability of individuals to gain education qualifications as well as involve themselves in apprenticeship leads to variety on qualifications which significantly make the job market competitive and by extension impact the quality of the workforce coming in from learning institutions which effectively solves the transition process. This significantly highlights the level of preparedness for managerial roles by the graduates.

6.2: Practical Implantations

Among the recommendations that could be adopted therefore to enhance an easier choice by graduates and also effectively enhance the transition process from of graduates into the job market include

Employers adopting apprenticeship to mentor students in their final year of the traditional degree programs so as to enhance their qualification as well as preparedness for the job market and managerial positions

Evaluate the qualifications of managerial positions to consider Apprenticeship degree graduates especially given the high level of managerial skill and experiences they often possess upon graduation.

Reference

- Ainley, P. and Rainbird, H., 2014. Apprenticeship: Towards a new paradigm of learning. Routledge.

- Albanese, A., Cappellari, L. and Leonardi, M., 2017. The effects of youth labor market reforms: evidence from Italian apprenticeships. Luxembourg Institute of Socio-Economic Research (LISER) Working Paper, (2017-13).

- Bai, Y.K., Wunderlich, S.M. and Weinstock, M., 2012. Employers' readiness for the mother‐friendly workplace: an elicitation study. Maternal & child nutrition, 8(4), pp.483-491.

- Bailey, T.R. ed., 2010. Learning to work: Employer involvement in school-to-work transition programs. Brookings Institution Press.

- Barone, C. and Ortiz, L., 2011. Overeducation among European University Graduates: a comparative analysis of its incidence and the importance of higher education differentiation. Higher Education, 61(3), pp.325-337.

- Belfield, C., 2010. Over-education: What influence does the workplace have?. Economics of Education Review, 29(2), pp.236-245.

- Belfield, C., 2010. Over-education: What influence does the workplace have?. Economics of Education Review, 29(2), pp.236-245.

- Jackson, D. and Wilton, N., 2017. Perceived employability among undergraduates and the importance of career self-management, work experience and individual characteristics. Higher Education Research & Development, 36(4), pp.747-762.

- Onwuegbuzie, A.J. and Leech, N.L., 2007. Sampling designs in qualitative research: Making the sampling process more public. Qualitative Report, 12(2), pp.238-254. Onwuegbuzie, A.J. and Leech, N.L., 2007. Sampling designs in qualitative research: Making the sampling process more public. Qualitative Report, 12(2), pp.238-254.

- Boden, R. and Nedeva, M., 2010. Employing discourse: universities and graduate ‘employability’. Journal of Education Policy, 25(1), pp.37-54.

- Brown, P., 2016. The transformation of higher education, credential competition, and the graduate labour market. Routledge handbook of the sociology of higher education, pp.197-207.

- Carroll, D. and Tani, M., 2013. Over-education of recent higher education graduates: New Australian panel evidence. Economics of Education Review, 32, pp.207-218.

- Danish, R.Q. and Usman, A., 2010. Impact of reward and recognition on job satisfaction and motivation: An empirical study from Pakistan. International journal of business and management, 5(2), p.159.

- Fuller, A. and Unwin, L. eds., 2014. Contemporary apprenticeship: International perspectives on an evolving model of learning. Routledge.

- Heyes, J. and Hastings, T., 2017. Economic and labour market change and policies: Before and beyond austerity in Europe. Trade Unions and Migrant Workers: New Contexts and Challenges in Europe, p.23.

- Hogg, M.A. and Adelman, J., 2013. Uncertainty–identity theory: Extreme groups, radical behavior, and authoritarian leadership. Journal of Social Issues, 69(3), pp.436-454.

- Jackson, D., 2013. Business graduate employability–where are we going wrong?. Higher Education Research & Development, 32(5), pp.776-790.

- Lee, D., 2012. Apprenticeships in England: an overview of current issues. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning, 2(3), pp.225-239.

- Lewis, P., Ryan, P. and Gospel, H., 2008. A hard sell? The prospects for apprenticeship in British retailing. Human Resource Management Journal, 18(1), pp.3-19.

- Muehlemann, S. and Wolter, S.C., 2011. Firm-sponsored training and poaching externalities in regional labor markets. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 41(6), pp.560-570.

- Ortiz, L. and Kucel, A., 2008. Do fields of study matter for over-education? The cases of Spain and Germany. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 49(4-5), pp.305-327.

- Pinto, L.H. and Ramalheira, D.C., 2017. Perceived employability of business graduates: The effect of academic performance and extracurricular activities. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 99, pp.165-178.

- Rowe, L., 2018. Managing degree apprenticeships through a work based learning framework: opportunities and challenges. In Enhancing Employability in Higher Education through Work Based Learning (pp. 51-69). Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

- Stuart, G.R., Rios-Aguilar, C. and Deil-Amen, R., 2014. “How much economic value does my credential have?” Reformulating Tinto’s model to study students’ persistence in community colleges. Community College Review, 42(4), pp.327-341.

- Taylor-Smith, E., Smith, S., Fabian, K., Berg, T., Meharg, D. and Varey, A., 2019, July. Bridging the Digital Skills Gap: Are computing degree apprenticeships the answer?. In Proceedings of the 2019 ACM Conference on Innovation and Technology in Computer Science Education (pp. 126-132).

- Wald, S. and Fang, T., 2008. Overeducated immigrants in the Canadian labour market: Evidence from the workplace and employee survey. Canadian Public Policy, 34(4), pp.457-479.

- Baker, D., 2018. Potential implications of degree apprenticeships for healthcare education. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning, IV(6), pp. 1-38.

- Dike, V. E., Odiwe, K. & Ehujor, D. M., 2015. Leadership and Management in the 21st Century Organizations: A Practical Approach. World Journal of Social Science Research, II(2), pp. 139-159.

- Holmes, L., 2001. Reconsidering Graduate Employability: the `graduate identity’ approach. Quality in Higher Education, VII(2), pp. 111-119.

- Mulkeen, J., Hussein A, A., Leigh, J. & Ward, P., 2017. Degree and Higher Level Apprenticeships: an empirical investigation of stakeholder perceptions of challenges and opportunities. Studies in Higher Education, XLIV(2), pp. 333-346.

- Smith, E., 2019. Apprenticeships and ‘future work’: are we ready?. International Journal of Training and Development, XII(1), pp. 102-115.

- Tomlinson, M., 2008. ‘The degree is not enough’: students’ perceptions of the role of higher education credentials for graduate work and employability. The British Journal of Sociology of Education, XIII(1), pp. 201-215.

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts