Home Musical Environments on Infants Aged 8-18 Months

Abstract

Children commonly report spontaneously enjoying singing, music exposure and interactions with musical environments. There are however, gaps on the effects informal musical environments have on infants aged 8-18 months developmental outcomes. Critically, there is no proper and comprehensive instrument with sound psychometric properties that can be utilised for assessment of home musical environments during infancy. This paper seeks to address this gap through the use of a validated Music@Home questionnaire. A pool of items was generated and administered to a relatively wide audience made up of parents and Exploratory factor analysis was utilised for purposes of identifying the different dimensions that made up home musical environments for infants and subsequently reducing the initial pool of items to a smaller number whose items were meaningful. Music@Home is without a doubt a reliable, and valid instrument that provides opportunities for systematically assessing the distinct aspects of home musical environments within families that have children who are aged 8-18 months. The findings of this study point to informal music having positive effects on the development of infants. For students who wish to seek assistance and guidance in mitigating the complexities encountered in such research, sources such as Psychology Dissertation Help are a great insight for them.

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION

1.1 Background to the study

In early human development, music is all-encompassing. The interactions between caregivers and infants are often musical and involve the playing of songs and singing of lullabies, in addition to rhythmic movements, including the clapping of hands to nursery rhymes, rocking and bouncing children in time with music (Virtala and Partanen, 2018). Children are even talked to in “paretense” (or infant-directed speech), characterised by richness in musical features, including pitch changes that are exaggerated. These musical phenomena play an important role in the early development of human beings (Brandt, Slevc and Gebrian, 2012). For instance, parentese has exaggerated cues which assist infants with becoming better at the discrimination of words. In addition, singing directed towards infants and caregiver-mediated musical play capture the attention of the infants and additionally places them in a better position of modulating their arousal and further synchronising with their caregivers, which goes a long way in promoting parental sensitivity (Dehaene-Lambertz et al. 2010). In effect, that correlated positively with security attachment and eventually brings about socio-emotional outcomes that are beneficial (Schafer and Eerola, 2020)

In the interactions between young infants and parents, music playing plays a relatively important role and that is because it has the potential of being engaging and motivating (Khaghaninejad and Fahandejsaadi-Shiraz, 2016). In addition, there are also associations between music activities and improved auditory, linguistic, and literary skills among adults and children. Therefore, early musical interventions and musical activities hold the potential of supporting development in those infants who are healthy and also those who are at risk of adverse outcomes. Owing to the nonverbal and playful nature of infants, musical interventions could even place infants who are too young for any other different rehabilitative programs (Engh, 2013).

Music, just like language, is a relatively complex system (Haslbeck and Bassler, 2018). Within language, there are smaller units including morphemes and phonemes which when combined form structures of a higher order, known as sentences and words. In music too, there are separate units, including durations and pitches which when combined form higher-order sequences including compositions and musical phrases. Within these musical and linguistic sequences, there are rhythmic and melodic patterns; with prosody in language and melody and rhythm in music (Jentschke, 2015).

The commonalities between music and speech become evident during the exploration of the perceptions of infants and production of sounds and the communication between mothers and infants. Among infants the remarkable sensitive to different melodic features including pitch and contour changes could come about from the early auditory, in utero maternal speech experience (Sulkin and Brodsky, 2015). It is notable that the musical elements of infant vocalisation that are important during the first year of life, which are temporal and melodic patterns and also manner of phonation, are produced in communicative contexts which are very specific. As aforementioned, adults speak in a different way when addressing children, known as Infant Directed Speech (IDS). That is characterised by a pitch that is high with melodic and rhythmic patterns that are also exaggerated. This is a type of speech that is richly intonated and that is quite efficient in conveying the prosodic features of the native language of an individual and also have the capabilities of shaping the vocal production of infants in their first year of life. It has indeed been argued that the cry of new-borns imitate their surrounding their surrounding speech prosody and their early vocal musical behaviours are linked to their native language`s prosodic characteristics. It is quite interesting that the capacities of processing speech prosody and perceiving intonational contours in melody are areas where language and music happen to overlap in the brain.

The discovery of musical abilities early enough among children has over time provided relatively fruitful ground for the study of language and music from a phylogenetic perspective. It appears that infants are immediately sensitive to music, the same way with language. Costa-Giomi and Ilari (2014), attribute this inclination as being shaped by human interactions in the content of forms that are culture-specific, that is, music systems and also languages that are different. The presence of shared features between music and language have contributed to the development of the hypothesis that song-like communication systems could be modern language`s phylogenetic precursors. It is worth noting that while there is still a lot of debate about the adaptive function of musical skills in evolutionary terms, there are several interesting observations of infants that point to the presence of very deep connections between the development of early communication and musicality. Child-directed singing has for example, been shown to be instrumental in the regulation of infant arousal (Ghazban, 2013) and in the establishment of the emotional bond between mothers and infants (l`Etoile, 2015). In addition, infants have been observed to display superior attention to sung communication, in comparison to spoken infant directed communication (Tsang et al. (2017); Nakata & Trehub (2004). In the same breath, the musical characteristics of the interactions between infants and mothers plays a critical role in the promotion of the development of socio-emotional regulation. It is also worth noting that the acquiring different linguistic and musical features including vocal learning and rhythm entertainment could rely on mechanisms of common learning with adaptive value for social development, for example, imitation. Generally, it is possible to draw quite interesting comparisons between the phylogeny of music and language when the focus is on the role they play in early development of languages and communication abilities.

It is accordingly expected that musical and linguistic skills would emerge in parallel and would be linked across early development. There is evidence from previous studies that points to this direction. Moreno et al., (2009); Francois and Schon (2011); and Kraus et al., (2014) did randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with school-aged children, which revealed the various language related advantages that come about from students participating in music groups/training. For instance, two years after participating in in painting versus music classes, the painting group was outperformed by the music group in controls of both behavioural and electrophysiological speech segmentation measures, that is, the abilities of extracting pseudo-words from continuous streams of artificial syllables (Francois et al. 2013). In a different study by Moreno et al. (2009), children (8-years old) who were receiving conventional music training spanning a period of 24 weeks showed improved performance in the abilities of pitch discrimination and reading measures. Quite notable, it is not possible to account for these differences by use of pre-existing traits that are found in musicians, for instance, general IQ and this is because these types of variables are controlled in the experiments.

Dege and Schwazer (2011), and Barac et al. (2011) carried out RCTs where they compared the effects of musical training on development of children compared to other types of training. They found out that music training had the effect of enhancing phonological awareness skills. Their findings suggest that music instruction features have the potential of strengthening different linguistic development aspects among young children. Anvari et al. (2002) carried out a correlational study and found that the melodic and rhythmic aspects of musical ability had associations with phonological awareness and early reading ability among children who were just 4 years old. However, the research with infants has so far been more limited.

The present study`s main goal is to shed light on the trajectory of development of the existing relationship between informal music and the development of early language. This study will focus on the interaction of music within the family, and its relationship with early language development in children, between the ages of 8-18 months.

1.2 Research questions

- What influences does informal musical experience have on the language development of infants aged between 8-18 months?

- Does musicality in the family predict later language development outcomes?

CHAPTER TWO: METHOD

This study is a joint project by me and four other collaborators. Although it is an extension to an already approved study (MORE 7404), a new application for Ethical approval was submitted and approved.

2.1 Research design

This study adopts a survey research design. Survey research designs are quantitative research procedures which involve the administration of surveys to just samples or even to entire populations for purposes of describing their characteristics, behaviours, opinions, and attitudes (Saris and Gallhofer, 2014). Quantitative data is collected through the use of questionnaires or interviews, after which the collected data is analysed statistically for purposes of describing trends about responses to questions and additionally testing research hypotheses and questions. A cross sectional survey approach is adopted and this involves the collection of data about a population over time (Nardi, 2018). The data is collected from parents of infants aged between 8-18 months.

The surveys were collected via Qualtrics, and distributed via social media, personal networks and snowballing techniques. Questionnaires will be used for data collection. Questionnaires are research instruments which are made up of a series of questions and which are utilised for purposes of gathering information from participants. The choice to use questionnaires over the other research instruments was for data collection in survey research was informed by the knowledge that questionnaires are inexpensive, practical, offer a quicker way to getting results, enable gathering information from large audiences, come in handy for comparison and contrasting other research, and allow easy analysis of results.

The independent factor would be age, with two levels of Independent Variable IV): 8 - 12 month old babies and 13 - 18 month old toddlers. The dependant variable would be CDI-UK for language development, and score on Music@Home (home musicality may be used as a covariate.

2.2 Participants

According to the main measures of this study, the target sample would be the primary caregivers or parents of the young infants who are aged between 8-18 months old, and should be native speakers of the English language or speak only English at home. Participants will be requested to provide information about their musical sophistication via the Gold-MSI (Mullensiefen et al. 2014) in order to check that the results would be, ideally, independent of musical preferences for specific styles, for example, pop music vs classical music. The Gold-MSI is considered a measurement instrument that is 1) both valid and reliable, and brief without sacrificing its good psychometric properties. 2) Multi-faceted instrument that distinguishes between the different musical sophistication aspects, and that 3) is sensitive to the differences among individuals who are not musicians.

2.3 Procedure

Participants are to be briefed in writing about the outline of the study and requested to consent to taking part in the study and sharing their anonymised data. The rights of anonymous data collection was explained, alongside the potential risk of disclosure of personal data used in the future, and of it being stored and published in academic journals. At the end of the procedure, debriefing was conducted, thanking the contributors for their time, and the rights of withdrawal within the two weeks of participating, will need be explained. After signing consent, participants completed the survey, which took approximately 30 minutes. At the end of the study the data were downloaded from Qualtrics and transferred to the SPSS software for data analysis.

2.4 Measures

Data were collected from the four types of measures:

- Music@Home-Infant (reference, and put copy in Appendix 1), measuring musical activities in the family.

- Stim-Q (reference, put copy in Appendix 2),, measuring general enrichment such as book reading or toys at home.

- CDI-UK(reference, put copy in Appendix 3),, measuring language and communication development.

- Gold-MSI short index (reference, put copy in Appendix 4), measuring parent musical sophistication such as attitudes, behaviours, and skills.

There were four sets of questionnaires containing different types of measures. Measures are those items in a research study to which participants provide responses. The first measure will be the Music@Home-Infant questionnaire which will come in handy in the assessment of the home musical environment within families. This instrument quantifies the length to which infant`s home environments are varied musically and enriched in ways that are specific. The StimQ questionnaire will be used for purposes of measuring the infant’s cognitive stimulation when at home. There are four subscales in the questionnaire which include availability of learning material (ALM), parental involvement in developmental activities (PIDA), parental verbal responsivity (PVR), and reading activities (READ). The other questionnaire, the United Kingdom Community Development Inventory (CDI-UK, Words & Gesture form, suitable 8-18 months), is a questionnaire completed by parents telling about the language and communication of their children. This measure comes in handy in establishing a comprehensive overview of the children`s first stages in language development, the children`s first word learning norms, and is a quick, inexpensive and relatively easy checklist useful for assessment of children`s language. The other questionnaire, the Gld-MSI reports on individual differences in music sophistication. The instrument measures an individual’s abilities to flexibly and effectively engage in music.

CHAPTER THREE: RESULTS

The SPSS software was used to analyse all the data that had been collected. To identify dimensions within the set of items that could possibly correspond with the questionnaires subscales, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was carried out. There were two factor extraction methods that typically been used in exploratory factor analysis that were implemented and these were maximum likelihood estimation and minimum residual factor analysis. Parallel analysis was used for purposes of the factor extraction.

The present study was targeted on infants aged between 8-18 months (n=53). These infants were placed into two age groups, those aged 8-13.5 (n=25) months with STD of 94.510 and others who were aged between 13.5-18 months (n=28) STD 87.258.

Reducing the number of items was one of the main intentions as this would go a long way in ensuring that an increasingly coherent tool that was also quick to administer was obtained. This item reduction procedure utilised the Schmid-Leiman factor analysis solution with maximum likelihood estimation. In this process, the optimal factor structure was recalculated after the end of every iteration. Thereafter, items were screened and subsequently removed at every other step of the analysis, if, their uniqueness value was high (>.7) and if they had relatively low loadings on multiple sub-factors. When the uniqueness value is high, this is usually an indication that there is a high amount of the variance of the item that is not explained by any of the models factors. The removal of each item was followed by the computation of the of a Schmid-Leiman factor model that was also based on optimal the optimal number of sub-factors that had been suggested at the previous stage. The final step involved the employment of the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) for purposes of examining the factorial validity of the models that had been constructed using the procedure that had been described. For the infant’s model, the factor residual variance was set to 1 and the different factors were set such that they were not correlated.

There were up to 17 items that were not included in the further analysis as their distributions were found to be highly skewed (skewness > 1.0). The initially hypothesised 12 dimensions were put through EFA. From the different criteria, it was clear that the optimal number of factors ranged 1-12. In addition, during the performance of the parallel analysis, an eigenvalue that was seven times bigger than the second factor was yielded during the performance of the parallel analysis.

It is possible to specify the developed model as either a higher-order or a bi-factor model. A higher-order model is one where the covariance between sub-factors of a lower-level are accounted for (Murray and Johnson, 2013). On the other hand, the bi-factor model is one in which the existence of a general factor is in parallel with sub-factors that are domain-specific that are considered as not being related to the general factor (Morgan et al. 2015). In the current case, it was concluded that a bi-factor approach would be more appropriate as it accounts for the existing conceptual commonality between items by directly influencing them, unlike in the higher-order model where the general factor has an indirect influence on items through sub-factors.

One-factor analysis was done and this was followed by the extraction of the matrix of residuals. From the parallel analysis on the residual matrix combined with the MAP and Kaiser`s criterion, it was revealed that there existed 5 sub-factors. This pointed to 5 being the optimal number of sub-factors. The next step involved designating appropriate labels to the 5 grouping that had been suggested by the sub-factors. The first grouping had items that were reflective of the attitudes of parents and their attitudes towards using music and development, and was therefore, named Parental beliefs. The second grouping was concerned with the activities of parents and their attitudes towards regulating the emotions of their children using music and singing, and was therefore labelled as Emotion regulation. The third grouping had a relationship with the engagement of children with musical activities and was named Child`s Active Engagement. In the fourth grouping, there were statements on singing activities that had been initiated by the parents and they were therefore named Parent Initiation of Music Making. In the fifth item, there were items that were concerned with music-making between parents and children and was named Parent Initiation of Music-Making.

For purposes of testing the bi-factor model, a CFA procedure was utilised and this was made up of a general factor that had been defined by the different items in the questionnaire`s reduced version and 5 sub-factors. After running the model in the first instance, an observation was made that there were two items whose loadings were weak on their respective sub-factors which suggested that they had to be removed. After the removal of the two items, the model was subsequently re-run.

Parental beliefs are representative of the notions that parents have with regards to music`s beneficial effects to the general development of their children. It is worth noting that the same cluster of questions that are reflective of the beliefs of parents in the Music@Home with other previous studies were uncovered during the analysis of the Infants. That is a suggestion that this is a facet of the home musical environment that is not dependent of the child`s age. Previous studies describing infant and young children`s home musical environments and those exploring the attitudes of parents in relation to the educational aspects of music have addressed this aspect (Dai and Schader, 2001; McPherson, 2009; Warren and Nugent, 2010; Walker and Shenker, 2010). From these studies it has been shown that the parents whose children go ahead to take part in music classes generally have positive beliefs about music education`s positive benefits and the important role that is played by music practice. The attitudes of parents have also been reported to be positively associated with the motivation and musical attainment of their children (Upitis et al. 2017). In addition, the most of the parents with infants indicated that they believed that music education had positive effects and further reported high music listening and singing frequency together (Ilari, 2018). When these different factors are taken together, they are a clear indication that the attitudes of parents and their beliefs are important influences on the musical experiences of their children in both formal and informal settings. The subscale therefore presents a relatively consistent measurement of the measurement of a dimension that makes a contribution in the provision of an increasingly complete picture of the home musical environment.

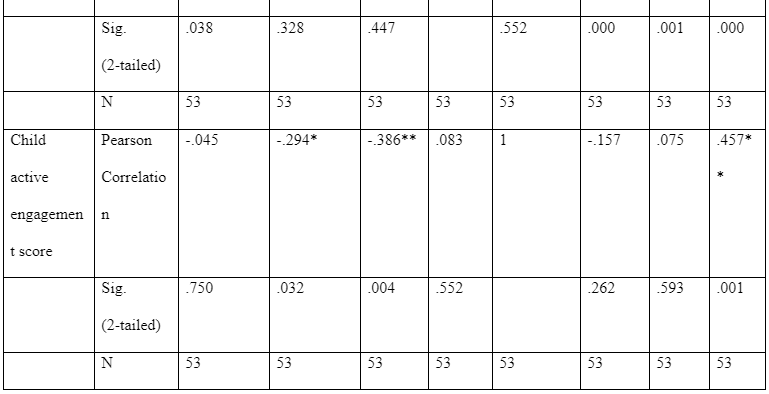

The child engagement score is representative of the active participation of children and the subsequent initiation of musical activities and is a factor that surfaces in the infant model. There were various musical behaviours that emerged as important for the model and these were reflective of the characteristics of the infants. An example was, “My child enjoys making sounds and actively interacts with musical instruments including those that are just toys.” Valerio et al. (2012) also addressed children`s engagement with music and their participation. They developed a parent-report questionnaire that was specifically aimed at documenting the musical behaviour of preschool children so that they could best meet the musical needs within school settings and childcare. There are other instances where the importance of observation and documentation of aspects of children`s music-related behaviour in musical development and research have been recognised. The inclusion of a relevant subscale in a systematic instrument that assesses informal home musical environments opens up new avenues for the exploration of the different ways through which the interplay of parent-child characteristics could affect the experiences of children as well as their developmental outcomes.

The Parent Initiation of Musical Behavior subscale indexed the music engagement that was triggered by the parents including making music and singing with the child. Without a doubt, the musical interactions between parents and children are an instrumental aspect of the home musical interactions. Associations have been recorded between higher frequency of these activities during the early years and positive outcomes including enhanced auditory sensitivity and enhanced vocabulary skills. Along with the beliefs of parents and their attitudes, the involvement of parents at home with their children is recognised as one of the important factors that have an influence on the musical attainment of children.

An observation is that music making and singing emerged as separate factors in the Music@Home-Infant, an indication that parents of children in different age groups could differ in the different ways through which they take part in the two activities. Without a doubt, infants aged between 8-18 months are engaged in active music-making in a lesser extent as compared to other older children, while the involvement of parents through singing seemingly holds a crucial role in the regulation of arousal and construction of emotional interactions among infants. In addition, when singing in infancy is approached as a separate dimension, which highlights the critical role played by the activity which could possibly carry for development related outcomes including language learning and socio-emotional and communicative development. Indeed, as a result of song`s melodic and rhythmic properties that place emphasis and further exaggerate the elements of speech, singing has been evidenced to play a facilitative role in phonetic learning in infants aged 8-18 months. There is also the possibility of infants benefitting from the combined input of music and their lyrics and that is because efficient information sources provide additional cues that place them in a better position to go about identifying structure in the first source (syllables and words). A proposal is made by Van Puyvelde and Franco (2015), that melodic patterns and ‘tonal synchrony’ could facilitate affective co-regulation and could also be representative of later social development.

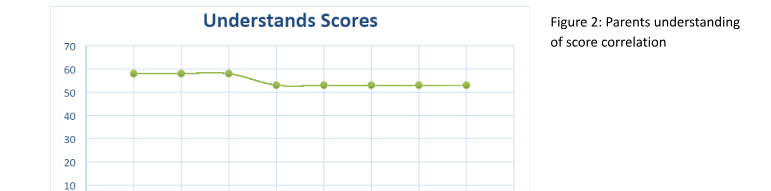

There were quite strong associations that were observed between the different subscales of Music@Home –Infant and the music involvement of parents, which is the music activities of parents. That effectively established the Music@Home questionnaires convergent validity. It is worth notion that the correlation coefficients, even though highly significant were less than .6 which is a suggestion that Music@Home provides a measure that is relevant even though not identical to the construct of the music activities of parents. It was also established that there existed divergent validity of the questionnaires and that is because weak to moderate associations were found between numerous dimensions of the Music@Home-Infant and two subscales that were drawn from Stim-Q which was a validated instrument that assessed young children`s home environmental quality. The results point to the possibility of disentangling the Music@Home questionnaire from the general engagements between parents and their children. An observation was made that there existed a significant correlation between the PIDA subscale and the Music@Home-Infant general factor that for infants, there exists stronger coupling between engagement in musical activities and promotion of learning in other different domains.

It is quite interesting that from the present study made an observation of the presence of relatively strong associations between the Child Engagement subscale of the Music@Home-Infant subscale and reading and parental involvement to developmental advance subscales. It is however, worth noting that because the subscale is reflective of the attitudes of infants and the behaviours they portray towards music, there is no likelihood that it assesses a concept that is similar to the general engagement of parents. Rather, there is the possibility that the finding hints to the presence of an association between the level of engagement between parents and their children in various activities and the attitudes of children towards the activities. Kuhl et al. (2019) in line with the view make an argument that interpersonal engagement could possibly have determinant effects on the arousal and attention of infants. In support of this argument, it is worth noting that the infant versions Child Engagement was the only factor that did not have a relationship with the musical characteristics of parents as measured by the Gold-MSI subscales (Musical Training and Active Engagement). That makes a suggestion that, young infants are not yet in a position where the personal interests of their parents could influence them and that they stand to benefit from joint activities.

There were differential associations that emerged between the Gold-MSI subscales and the Music@Home-Infant. Specifically, the general factor of the Music@Home and the majority of the subscales showed relatively strong associations with the two factors and from the most of the subscales, it became clear that their existed strong associations with the two factors. That is consistent with the findings of Custodero and Johnson-Green (2008), who also found strong relationships with all the factors. They reported that those parents who had musical training has higher likelihood of musically engaging with infants.

Without a doubt, the Music@Home-Infant questionnaire provided the researcher with a relatively novel, valid, and reliable and quick-to-adminster instrument for systematically assessing home musical environments. Quite importantly, the instrument brought together for the first time varying novel dimensions including breadth of musical exposure and subsequently combined them with increasingly and typically studies musical experience aspects that allowed for a comprehensive tool that effectively captured the extent of musical activities occurring informally within the infant`s homes.

For purposes of measuring whether there were associations between the characteristics of parents that were relevant to music engagement, the survey also included, two subscales of the GoldMsi and two sub-scales drawm from the Stim-Q Cognitive Home Environment. The Stim-Q came in handy in the assessment of the quality of home learning environments. Each subscale that corresponded with the factors of the Music@Home questionnaire was assessed to determine its internal reliability. By summing up item scores, it became possible to calculate the scores for each Music@Home subscale and also for the general factors. The subscales for the infant model showed moderate to very good reliability. Only Emotional Regulation did not show the same, but showed high test-retest correlations. From these results, there is a suggestion that the items of Emotional Regulation corresponding to a separate grouping is questionable and that led to their exclusion from subsequent analysis.

CHAPTER FOUR: DISCUSSION

Research question 1: What influences does informal music experience have on the language development of infants aged between 8-18 months?

There is strong evidence provided that the timing and melodic aspects of musical processing, have associations with grammar and phonological awareness among infants (Gordon et al. 2015; Politimou et al. 2019; Swaminathan and Schellenberg, 2020). The abilities to specifically time tempo and rhythm perceptions and beat synchronisation were associated with phonological awareness quite consistently. Melodic processing was however particularly associated with language grammar (Carr and White-Schwoch, 2014). From the regression analysis, it was revealed that beat synchronisation and perceptions of rhythm were the most significant phonological awareness predictors. These musical predictors made a contribution to phonological awareness above and beyond cognitive skills that included non-verbal ability, and verbal memory. From these findings, it is quite clear that there exists a relatively strong relationship between phonological awareness and timing skills. The same has been reported for older children by Anvari et al. (2002). Verney (2013), and Huss et al., (2011). From the present study, there is evidence that the link also extends to the perceptions of rhythmic patterns in infants.

There has been growing interest towards the incorporation of informal musical activities in clinical interventions for multiple reasons. This interest is partly fuelled by a pioneered randomised controlled trial that was carried out by Sarkamo et al. (2014) that showed that listening to music everyday supported cognitive recovery after stroke. Stroke patients in the study who had been assigned to a self-selected music listening group showed greater verbal memory recovery and focused attention, when they were compared with those patients who were in an audio-book listening group. These were quite encouraging findings which indicated that listening to music on a daily basis had wide ranging and deep effects on the brain. Childhood informal music activities could perhaps be harnessed for purposes of tuning auditory processing. That would come in handy for those children who have language development disorders since there is evidence that infant auditory discrimination is an indicator of language skills in later life, and that basic auditory dysfunction could be a key feature of dyslexia. In addition, there are attention related effects of informal music on the development of infants which point to the potential of music activities to support the recovery of hearing in those children who have had cochlear implants.

In contrast to the various musical activities that have been reported to have beneficial effects on the development of the brain, music could have an especially strong motivational component from very early in life and could suit children`s perceptual and motor capabilities. Therefore, musical activities could be in a special position to shape the development of the brain during the early years of life that are characterised by heightened neuroplasticity.

Research Question 2: Does Musicality in the family predict later language development?

The present study provides evidence that environments that are musically rich have beneficial effects on children`s auditory abilities. We make a suggestion that these effects are not specific to the domain of music but informal music activities have the potential of promoting generalised enhancement of auditory processing. When these skills are enhanced, that would have a significant effect on later development of attention and language. There are critical roles played by the social aspects of musical activities in the various effects of musical experience in developing auditory skills. The majority of the musical activities that children engage in take place in social situations, and that is for obvious reasons. Also, social interactions are therefore, quite important components of early music experiences. In Kirschner and Tomasello (2010), a direct comparison of the tapping of a drum to a rhythm in social and non-social settings was done and it was revealed that there was increasingly accurate spontaneous drumming during drumming together with adults than in those instances when machines of prerecorded beats were used. In addition, the findings that social interactions play an important role in the learning of native speech sound points to social interactions having the potential of facilitating early perceptual learning in the domain of music.

According to Cornelius and Natvig (2018), music is a primarily social experience where the intentions behind the motor actions required for production of music signals are understood. They suggest that this process is reliant on the mirror neuron system and the making of music has the potential of promoting positive social interaction and that is precisely because of the system`s engagement. Generally, it is believed that mirror neurons encode motor goals and intentions and therefore offer support for the understanding of actions, interaction and social learning. Whether the mirror neuron system is involved or not, there is an association between the making of music and positive social behaviour (Sunderland, Lewandowsi and Bendrups, 2018). For instance, laGasse (2017), reported that children showed increasingly prosocial behaviour after instances of joint music making when a comparison was made with non-musical cooperation. Sharda, Tuerkm Chowdgury and Jamey (2018), however, propose the associative learning account which holds that the capability of mirror neurons to match observed and executed actions could only be acquired through experience. Therefore, music-making that is interactive between parents and their children could either possibly be supported by the mirror neuron system or as a naturally engaging learning platform for the development of the neurons matching properties.

Research carried out by the University of Queensland shows that even simply jamming with infants as they play has the potential of positively impacting them for the rest of their lives. Shared musical activities at home have been found to be capable of paying dividends in the long run. Williams (2018), report that informal music has various benefits for infants ranging from the development of their attention longevity, numeracy, pro-social skills, vocabulary and emotional regulation.

There is need for studies carried out in the future to investigate these effects only hold for childhood, that is, whether there exists an early sensitive period for the effects and whether the periods are fixed relatively or whether experience makes them malleable. Conner, Baker and Allor (2020), suggest that multiple language exposure at infancy has the potential of extending the native speech sound learning sensitive period. Therefore, there is need to carry out longitudinal studies focused on infants for purposes of mapping the stability between musical activities that are informal and childhood auditory skills in addition to their implications for later auditory development. Very important to note is that there should be experimental interventions studies aimed at disentangling the direction of causality in the associations and testing the feasibility of incorporation of daily musical activities in the treatment and prevention of auditory processing impairments.

When everything is taken together, the present study`s findings point to the potential of music as part of daily informal activities to improve various cognitive functions and therefore encourage music use in multiple education settings including day-cares and schools for those who either have special needs or those who do not have any special needs. The review of the benefits of music even in the absence of formal instrumental training potentially offers for the modulation of children`s basic neurocognitive functions.

Recommendations

Consider ditching flashing and beeping toys and instead go for the tactile and inexpensive musical instruments including bongos and any other percussion instruments together with recorders and toy piano`s.

Shared experiences are very important and are necessary for results to be obtained. Parents should therefore, block off some of their time and join their infants in music lay. This does not need to be strictly regular and could simply be done whenever parents feel like they need to burn off some energy.

Parents should go for simple instruments like pots and wooden spoons which are readily available in their kitchens and should shun any expensive items that they have to buy from the shop.

It is important that parents should not focus on any single and specific goal. So long as their children are having fun with exploration of the processes of making sounds, then they are doing a good job.

Parents should also put efforts to ensure that they face their children during the play sessions as this goes a long way in helping with the social bonding aspects of their exercises. Together with the benefits that these musical activities will have on the development of their children, they will also get to enjoy the bonding sessions.

Reference

- Anvari, S.H., Trainor, L.J., Woodside, J. and Levy, B.A., 2002. Relations among musical skills, phonological processing, and early reading ability in preschool children. Journal of experimental child psychology, 83(2), pp.111-130.

- Anvari, S.H., Trainor, L.J., Woodside, J. and Levy, B.A., 2002. Relations among musical skills, phonological processing, and early reading ability in preschool children. Journal of experimental child psychology, 83(2), pp.111-130.

- Brandt, A.K., Slevc, R. and Gebrian, M., 2012. Music and early language acquisition. Frontiers in psychology, 3, p.327.

- Carr, K.W., White-Schwoch, T., Tierney, A.T., Strait, D.L. and Kraus, N., 2014. Beat synchronization predicts neural speech encoding and reading readiness in preschoolers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(40), pp.14559-14564.

- Chen‐Hafteck, L., 1997. Music and language development in early childhood: Integrating past research in the two domains. Early child development and care, 130(1), pp.85-97.

- Conner, C., Baker, D.L. and Allor, J.H., 2020. Multiple language exposure for children with autism spectrum disorder from culturally and linguistically diverse communities. Bilingual Research Journal, 43(3), pp.286-303.

- Costa-Giomi, E. and Ilari, B., 2014. Infants’ preferential attention to sung and spoken stimuli. Journal of Research in Music Education, 62(2), pp.188-194.

- Custodero, L.A. and Johnson‐Green, E.A., 2008. Caregiving in counterpoint: Reciprocal influences in the musical parenting of younger and older infants. Early Child Development and Care, 178(1), pp.15-39.

- de l’Etoile, S.K., 2015. Self-regulation and infant-directed singing in infants with down syndrome. The Journal of Music Therapy, 52(2), pp.195-220.

- Degé, F. and Schwarzer, G., 2011. The effect of a music program on phonological awareness in preschoolers. Frontiers in psychology, 2, p.124.

- Dehaene-Lambertz, G., Montavont, A., Jobert, A., Allirol, L., Dubois, J., Hertz-Pannier, L. and Dehaene, S., 2010. Language or music, mother or Mozart? Structural and environmental influences on infants’ language networks. Brain and language, 114(2), pp.53-65.

- Engh, D., 2013. Why use music in English language learning? A survey of the literature. English Language Teaching, 6(2), pp.113-127.

- Francois, C. and Schön, D., 2011. Musical expertise boosts implicit learning of both musical and linguistic structures. Cerebral Cortex, 21(10), pp.2357-2365.

- François, C., Chobert, J., Besson, M. and Schön, D., 2013. Music training for the development of speech segmentation. Cerebral Cortex, 23(9), pp.2038-2043.

- Ghazban, N., 2013. Emotion regulation in infants using maternal singing and speech. Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Ryerson University, Toronto, Canada.

- Gordon, R.L., Shivers, C.M., Wieland, E.A., Kotz, S.A., Yoder, P.J. and Devin McAuley, J., 2015. Musical rhythm discrimination explains individual differences in grammar skills in children. Developmental science, 18(4), pp.635-644.

- Haslbeck, F.B. and Bassler, D., 2018. Music from the very beginning—a neuroscience-based framework for music as therapy for preterm infants and their parents. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience, 12, p.112.

- Huss, M., Verney, J.P., Fosker, T., Mead, N. and Goswami, U., 2011. Music, rhythm, rise time perception and developmental dyslexia: perception of musical meter predicts reading and phonology. Cortex, 47(6), pp.674-689.

- Ilari, B., 2018. Musical parenting and music education: Integrating research and practice. Update: Applications of Research in Music Education, 36(2), pp.45-52.

- Jentschke, S., 2015. The relationship between music and language. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK,.

- Kirschner, S. and Tomasello, M., 2010. Joint music making promotes prosocial behavior in 4-year-old children. Evolution and Human Behavior, 31(5), pp.354-364.

- Kraus, N., Hornickel, J., Strait, D.L., Slater, J. and Thompson, E., 2014. Engagement in community music classes sparks neuroplasticity and language development in children from disadvantaged backgrounds. Frontiers in psychology, 5, p.1403.

- Kraus, N. and Slater, J., 2015. Music and language: relations and disconnections. Handbook of clinical neurology, 129, pp.207-222.

- Kuhl, P.K., Lim, S.S., Guerriero, S. and van Damme, D., 2019. Music, cognition and education.

- LaGasse, A.B., 2017. Social outcomes in children with autism spectrum disorder: a review of music therapy outcomes. Patient related outcome measures, 8, p.23.

- McPherson, G.E., 2009. The role of parents in children's musical development. Psychology of Music, 37(1), pp.91-110.

- Moreno, S., Marques, C., Santos, A., Santos, M., Castro, S.L. and Besson, M., 2009. Musical training influences linguistic abilities in 8-year-old children: more evidence for brain plasticity. Cerebral cortex, 19(3), pp.712-723.

- Moreno, S., Bialystok, E., Barac, R., Schellenberg, E.G., Cepeda, N.J. and Chau, T., 2011. Short-term music training enhances verbal intelligence and executive function. Psychological science, 22(11), pp.1425-1433.

- Morgan, G.B., Hodge, K.J., Wells, K.E. and Watkins, M.W., 2015. Are fit indices biased in favor of bi-factor models in cognitive ability research?: A comparison of fit in correlated factors, higher-order, and bi-factor models via Monte Carlo simulations. Journal of Intelligence, 3(1), pp.2-20.

- Müllensiefen, D., Gingras, B., Musil, J. and Stewart, L., 2014. The musicality of non-musicians: an index for assessing musical sophistication in the general population. PloS one, 9(2), p.e89642.

- Murray, A.L. and Johnson, W., 2013. The limitations of model fit in comparing the bi-factor versus higher-order models of human cognitive ability structure. Intelligence, 41(5), pp.407-422.

- Nakata, T. and Trehub, S.E., 2004. Infants’ responsiveness to maternal speech and singing. Infant Behavior and Development, 27(4), pp.455-464.

- Nardi, P.M., 2018. Doing survey research: A guide to quantitative methods. Routledge.

- Politimou, N., Dalla Bella, S., Farrugia, N. and Franco, F., 2019. Born to speak and sing: Musical predictors of language development in pre-schoolers. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, p.948.

- Politimou, N., Dalla Bella, S., Farrugia, N. and Franco, F., 2019. Born to speak and sing: Musical predictors of language development in pre-schoolers. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, p.948.

- Politimou, N., Dalla Bella, S., Farrugia, N. and Franco, F., 2019. Born to speak and sing: Musical predictors of language development in pre-schoolers. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, p.948.

- Särkämö, T., Tervaniemi, M., Laitinen, S., Numminen, A., Kurki, M., Johnson, J.K. and Rantanen, P., 2014. Cognitive, emotional, and social benefits of regular musical activities in early dementia: randomized controlled study. The Gerontologist, 54(4), pp.634-650.

- Schäfer, K. and Eerola, T., 2020. How listening to music and engagement with other media provide a sense of belonging: an exploratory study of social surrogacy. Psychology of Music, 48(2), pp.232-251.

- Sharda, M., Tuerk, C., Chowdhury, R., Jamey, K., Foster, N., Custo-Blanch, M., Tan, M., Nadig, A. and Hyde, K., 2018. Music improves social communication and auditory–motor connectivity in children with autism. Translational psychiatry, 8(1), pp.1-13.

- Simpkins, S.D., Vest, A.E., Dawes, N.P. and Neuman, K.I., 2010. Dynamic relations between parents' behaviors and children's motivational beliefs in sports and music. Parenting: Science and Practice, 10(2), pp.97-118.

- Sulkin, I. and Brodsky, W., 2015. Parental preferences to music stimuli of devices and playthings for babies, infants, and toddlers. Psychology of Music, 43(3), pp.307-320.

- Sunderland, N., Lewandowski, N., Bendrups, D. and Bartleet, B.L., 2018. Music, health and wellbeing. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Swaminathan, S. and Schellenberg, E.G., 2020. Musical ability, music training, and language ability in childhood. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 46(12), p.2340.

- Tsang, C.D., Falk, S. and Hessel, A., 2017. Infants prefer infant‐directed song over speech. Child development, 88(4), pp.1207-1215.

- Upitis, R., Abrami, P.C., Brook, J. and King, M., 2017. Parental involvement in children’s independent music lessons. Music Education Research, 19(1), pp.74-98.

- Valerio, W.H., Reynolds, A.M., Morgan, G.B. and McNair, A.A., 2012. Construct validity of the children’s music-related behavior questionnaire. Journal of Research in Music Education, 60(2), pp.186-200.

- Verney, J.P., 2013. Rhythmic perception and entrainment in 5-year-old children (Doctoral dissertation, University of Cambridge).

- Virtala, P.M. and Partanen, E.J., 2018. Can very early music interventions promote at-risk infants’ development?. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences.

- Walker, J.M., Shenker, S.S. and Hoover-Dempsey, K.V., 2010. Why do parents become involved in their children's education? Implications for school counselors. Professional School Counseling, 14(1), p.2156759X1001400104.

- Warren, P. and Nugent, N., 2010. The Music Connections Programme: Parents' perceptions of their children's involvement in music therapy. New Zealand Journal of music therapy, (8), pp.8-33.

- Williams, K.E., 2018. Moving to the beat: Using music, rhythm, and movement to enhance self-regulation in early childhood classrooms. International Journal of Early Childhood, 50(1), pp.85-100.

Appendices

Ethics statement

This research will comply fully with research ethics norms and the codes and practices established by the Economics and Social Research Council (ESRC). Human participants will be involved in this research, commencing with a face-to-face survey of parents with infants aged between 8-18 months. Being the principal investigator, I will take it upon myself to explain what the research is about to the participants. A one-page project information sheet will be given to every research participant, outlining the study`s purpose, details on who is undertaking and financing the study, and how it`s dissemination and use will happen.

In the project information sheet, there will also be contact information, to be used by the participants in the event they require any additional information or have intentions of retracting information or withdrawing participation at any point. The information sheet also provides information on the different ways through which confidentiality and anonymity is accorded. If necessary, the researcher will undertake to translate the information sheet. Research participation will be voluntary and all participants will be required to give their informed consent.

Personal identifiers are removed for purposes of assuring the anonymity of the research participants and instead, pseudonyms and research unit codes are used. The collected raw data will be collated in password protected computers, only accessible by the principal investigator. Subsequently, the data will be systemised and stored in two-password protected external storage drives. These storage drives will be securely stored by the principal investigator.

Take a deeper dive into Experienced Educator Seeking Teaching Position with our additional resources.

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts