Rehabilitative Strategies for Youth Offenders

Introduction

This explorative study seeks to examine effective rehabilitative strategies for youths engaged in criminal activities.

The three objectives of the study are;

To audit rehabilitative measures encountered by the young people in an institutional setting

To explore the perceived effectiveness of the measure from the perspective of the young people, the setting’s staff and parents/carers.

recommendations

In the criminal justice system, everyone is grappling with the concern of serving timely justice, and in this regard, a discussion on prisoner's rehabilitation might seem futile. The term rehabilitation in correctional context is ostensibly an idealized terminology. Therefore, rehabilitation is among the belligerent attributes of criminology and penology.

Crime and punishment have been crucial attributes while scheming rehabilitation approaches. As time times change does not only the conception of crime and punishment change but also the intervention strategies. The concept of reformation is believed to begin during the 19th century in western countries. Several state programs have attempted early intervention while national funding for community ingenuities have enabled autonomous groups to solve problems in new approaches. The most Ethical guidelines should be adhered with at all times when working with a research project in an educational context. This action is most prevalent when children, for instance, are involved and also when conducting an expert-based study.

There are several ethical guidelines involved in this investigation; for instance, because the participants in this study were below the adult age (18), the researcher sought consent from the parents. This ethical practice, however, has received several contestations, including Siegle (2018) and the British Educational Research Authority (BERA) (2018). According to Siegle, consent to participate in research should be given by the children's parents. On the other hand, BERA (2018) argues that any participant should provide consent individually and should have the autonomy of withdrawing their participation at any point in time without reason. However, this study sought permission from parents before proceeding further. The researcher informed the participants about their rights, especially the right to withdraw from the processes. Lastly, the researcher's educational institution provided ethical clearing before beginning the research and also the publication of the findings.

Continue your journey with our comprehensive guide to Youth Development.

This submission was conducted within an all-girls school SEN provision, South Park. The institution will be called as 'Setting X' for ethical reasons; setting X is situated in the middle of a council housing estate. The students in setting X presents an array of needs and requirements including Social, Emotional & Mental Health (SEMH), and Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) among others.

Based on the researcher's dissertation in the UK context, it can be stated that rehabilitation is an oversight terminology in a correctional environment that involves the reformative actions in the form of life skills, education, vocational training, art and music among others. The term ‘reformation of prisoners' is commonly used to imply keeping inmates busy to ensure they do not get engaged in antisocial activities in the prisons. This phrase, at times, includes several activities that dilute the very essence of reformation. Practically, while planning reformation approaches, one should design a plan that maximizes the participation of the offenders and develop a further interest to bring change at psychological and emotional levels. This approach helps offenders build their skills. Nevertheless, because the issue of increased numbers in prisons, which is also a global concern, alongside the scarcity of human and financial resources, the aim of constructing personalized plans are shelved, and the emphasis in fitting all the individuals into one framework takes on.

Crime in the UK

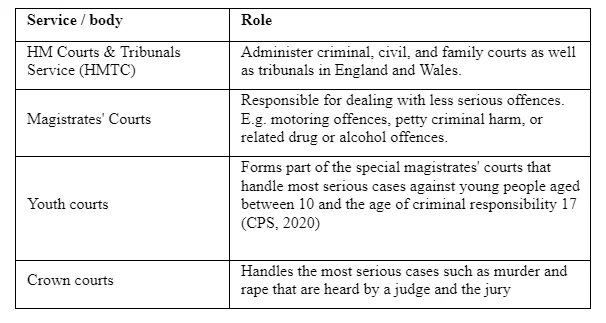

In the UK, the crime is identified as all acts of violence or non-violence that happen within the territory of the four countries. Courts and police systems operate in different judicial systems of the four countries and are separated into three categories; the HM courts & Tribunals Service (HMTC), the magistrates' courts, the youth courts (CPS, 2020). Their roles are identified in table one. All these are under the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS), the CPS collaboratively works with the police, courts, and the solicitor general's office among other entities in the Criminal Justice System (CJS). The Home office and the government department share responsibility for reducing and preventing crime. These two entities are also responsible for law enforcement in the country. On the other hand, the ministry of justice runs the justice system, which falls under the CPS and Procurator Fiscal Service (PFS) that functions as the only public prosecutor in Scotland and, therefore, responsible for the prosecution of crimes in the locality.

The crime statistics of both England and Wales show that crime rates in both countries are lower than EU trends. In this regard, today, the UK crime rate is at its lowest for once in 30 years. Notably, in 1995, the reported number of crimes stood at 4.2 million as compared with 2012's 1.92 million crimes (CPS, 2020).

The Youth Justice System in the UK

The primary aim of the Youth Justice System (YJS) in the UK is to inhibit young people (under the age of 18) from engaging in offences and also to address the needs of such a population (Crawford & Newburn, 2013). YJS is a non-departmental public institution established under the Crime and Disorder Act 1998. It consists of 290 board members sponsored by the Ministry of Justice, who are appointed by the Secretary of State for Justice. The system in itself is quite smaller than the adult justice system. Apart from preventing young people from committing offences, YJS also coordinates, counsels, and impels all functions in the youth justice system to support young people's needs to live successful and crime-free lives (Goldson & Muncie, 2009). Additionally, YJS aims to protect the public and support the victims by providing for their needs. YJS in both England and Wales involves a collaboration of agencies that coordinate activities to help youths. Some of these organizations include Youth Offending Teams, the Police and Crown Prosecution Service, the Judiciary, secure accommodation contributors, secure training centres, and safe children's homes (Andrews & Bonta, 2010).

The minimum age of criminal responsibility

The age of criminal responsibility is when a child crosses into the criminal justice system and can be lawfully indicted for an established transgression. In the UK, the law identifies the age to be ten years. Kids below the age of ten cannot be arrested; on the other hand, children of ages between 10 and 17 can be detained and charged in court (Taylor, 2016). However, persons from all age groups are treated differently, this is because, and adult offenders are served by crown and magistrates courts while youth courts serve youth offenders. They are bestowed in varied sentences and are not sent to fully-grown persons' prison but exceptional secure amenities. Additionally, people over 18 years are considered as adults, but if they are less 25 years of age, they are not sent to a full adult prison, instead of an amenity that retains 18-25-year-olds (Čehajić-Clancy et al., 2011).

Looking for further insights on Environmental Science Dissertation Topics? Click here.

Data on kids as targets and criminals

The number of novel entrants to the YJS has continuously been reducing. The latest statistics show that in December 2014, there were 21,016 first-time offenders as compared to 23,327 in the previous year, a drop of 11%. Since 2006, the number of fresh entrants to the YJS has dropped significantly by 81% since its peak level and by 78% since the peak level to December 2004. The most recent statistics (2015) show that the rate of first-time entrants per a hundred thousand population has dropped by 10 per cent from four hundred and fifty to four hundred and five in the last year. In March 2018, the first time entrants had fallen by 18% since April 2018; the number of children (10-17 years) given a caution or sentence has fallen by 83% over the last ten years, with a 19% drop in 2018 (YJB, 2020). The decrease in the number of first-time offenders since 2006 represents both the reduction of the crime rates including young people being cautioned (A warning or reprimand) as well as the reduction in the numbers of youths found culpable for offences in all courts. Some of the agencies collaborating with YJS, such as the Work by Youth offending teams (YOTs) employing crime prevention initiatives, including restorative justice disposals and triage programs, could be the main reason for the fall of first-time entrants (Williams & Steinberg, 2011). The total number of young people (under the age of 18) in custody in 2015 was 100,462, which represents a drop by 13.2% contrasted with the number in 2014 and by 67% since 2002 when the figure was at 3,200. The decrease in the rates of first-time entrants could have interposed to this situation. Besides the Youth rehabilitation Order initiated in late 2009, provides more elasticity regarding involvements provided to the youths as an item to the broader community sentence. Several spheres of the Youth Justice Board (YJB) efforts could also be linked to more youths being diverted from custodial centres. Some of them include; Determined interventions to increase awareness of distinct custody rates among custody authority spheres

Literature review

The role of literature is to show knowledge on previous studies regarding the effective rehabilitation strategies in support of juveniles for correctional function. The findings of this section will inform the methodology and consequent research.

Rehabilitation strategies

Rehabilitation is described as efforts, including treatment or programming, to stop offenders from engaging in criminal activities. According to Andrews & Bonta (2010), rehabilitation is a crime prevention approach based on the logic that offenders could transform and lead crime-free lives in the community. Whereas other preventative strategies seem to influence youths away from engaging in criminal and delinquency before they have done so, rehabilitation approaches target individuals who have already involved themselves in illegal activities. Rehabilitation is also applied as a tertiary crime prevention program (Menon et al., 2009). Besides, these programs can be offered within or as part of another criminal justice approval, including confinement or probation; however, this could not be a necessity of rehabilitative programming. There have been several intervention efforts on rehabilitation strategies in the UK in the past two decades. For instance, in January 2011, Graham Allen MP fashioned the first of two reports for the government on early intervention termed as 'the next steps' (Allen, 2011). The Allen report emphasizes on the approaches targeting 0-3 years and their families to foster social and emotional growth. There is substantial evidence showing that such programmers often aiming at-risk youths in deprived parts of the country, and partaking appropriate wide-scoped objectives could generate a variety of roles. Besides other endings, these interventions could lessen the risk that young people will advance inconsiderate or illegal behaviours later in life. Therefore, this submission strongly endorses the approach of positive the development of well-grounded early intervention platforms of this brand. Though useful, these wide-scoped early strategies with children could be; still, there could be some youths who could become entangled in criminal activities or belligerent behaviour anyway as they get older. Nevertheless, with this argument, the Government's Early Intervention incentives are not restricted to early years but also involve the scope of local authorities' undertakings with teenagers at risk or already engaged in antisocial behaviour. Thus, as an accessory to the Allen review, this dissertation focuses on programs that target at preventing the development of antisocial behaviour among children and teenagers or which aim to avert a configuration of antisocial or criminal behaviour from being engrained. This submission aims at offering a wide-ranging comprehension of fundamental features of 'what works' with regards to early intercessions to avert or lessen crime among young people or antisocial behaviour. The submission draws substantiation from transnational works of literature, especially the US, where the evidence base is quite firm. By analyzing the US evidence, this report provides an analytical assessment of youth crime strategies in the UK where empirical proof is less strong.

This collection of best works of literature and adept opinions will further the generation of robust and most favourable rehabilitation strategies. Besides, this submission identifies the differences in the validation and recommends areas that should be researched further.

Rehabilitative programs were an overriding response to a criminal deviating until worries began to increase during the 1950s and 1970s. The criticizers of this program questioned the utilization of discretion provided to state officials to determine and deliver rehabilitation as a sentence contrasted with its usage as a method of control and discrimination. During this period, several studies note that rehabilitative efforts were not functional. This tendency, however, culminated after Dr Robertson's popular publication on indoctrination in a young-offenders environment, which raised the question of whether existing rehabilitation strategies were working (Lipton et al., 1975). Martinson's work did not, however, culminate in the conversation regarding rehabilitation. Instead, critics jumped at the problem to demonstrate that rehabilitation approaches do have a promise (Gendreau, 1981; Cullen, 2005). However, Martinson reversed his original argument and highlighted positive impacts among various programs, including psychotherapy, group counselling supervision, and other plans. Even though Martinson recanted his original position and despite the outcomes of several other studies that demonstrated the utility of rehabilitation strategies, what followed was an anti- treatment debate that market several policy conversations throughout the 1980s. A number of authors documented several affirmative rehabilitative programs in the next two decades (Cullen and Gendreau, 1989; Lab & Whitehead, 1990). The 'what works' debate fundamentally leads to teasing out the attributes and treatment programs that help reduce the tendency of known offenders. Traditionally, thus, the primary objective and primary predictor of an effective rehabilitation program are whether program contestants attain a lesser recidivism rate than non-contestants do. Nevertheless, discoursing about 'what works' does not seem as simple as might be expected. There are several existing assessments on the rehabilitative determination (Wormith et al., 2007), and it would be difficult to evaluate every review and determine what could be the best practices for the youth. However, meta-analytic research works help astound this unnerving task by combining the conclusions of several pieces of research at once. Several recent publications addressing some of the inherent failures of the current system for dealing with youth crime and antisocial behaviour in the UK are in place (Chambers et al., 2009; Independent commission, 2010; Smith, 2010). The most notable concerns from these publications involve the levels of expenditure on implementation, courts, and the utilization of young offender facilities. Even though there seems to be a decline in youth imprisonment, the number is still quite high as compared to twenty years ago; notably, crime rates have dropped significantly over the same length (Smith, 2010). Another most profound statistic is that youth imprisonment is higher in England and Wales than in other countries, including France and Germany. Despite the very many empirical-based rejections of the 'nothing works' assertion, some experts continue to emphasize that rehabilitation approaches are not efficient because they are soft on criminals. These opponents call for harsher sentences and soldier treatment approaches to incapacitate the offenders. Besides, they call for heightened observation of offenders' population via expansion of law enforcement capacity (Ward & Maruna, 2007). Some of these people accentuate that administrations need to redirect resources they currently allocate to rehabilitation programs into the construction and policing of prisons. However, most researchers encourage the government to continue with rehabilitation approaches over restriction and prostration tactics (Landenberger &Lipsey, 2005; MacKenzie, 2006; Lipsey & Cullen, 2007). From the extensive support arising from a significant number of shreds of evidence, it is safe to say that rehabilitation exertions can help to reduce violence and other crimes. And therefore, the weight of this paper will be on this argument.

Public endorsement for Rehabilitation efforts

While the dominant attitude among the public is to get tough on crime, most of the citizens accentuate that rehabilitation programs weight on having a substantial impact on offenders. For instance, in America, research shows that the approval for rehabilitation efforts among citizens has been quite positive for over 20 years. In the late 1980s, 78% of the citizens preferred rehabilitation efforts as part of youth sentencing (Nagin et al., 2006). Besides, similar findings were reported in the early 1980s as well as the 90s showing solidity in public approval for rehabilitation efforts. In this regard, Cullen (2005) argues that even though the citizens are punitive and criminal treatment has been criticized regularly, Americans, however, firmly believe that determinations to put offenders on rehabilitation programs should be taken (P.12-13). Notably, most citizens support rehabilitation efforts for young people; for instance, a survey in Ontario done by Barber & Doob in 2004 finds that participants felt that rehabilitation efforts for young offenders seem to be more important than adults (Barber & Doob, 2004). Besides, the public perceived that incapacitation and restriction are not entirely helpful for young offenders compared with adult offenders. When asked to rate the significance of rehabilitative measures as a function of youth sentencing, most respondents rated rehabilitation efforts highly (8.1) on a scale of 1 to 10 with 10 representing highly essential and one less important (ibid). The same question was asked to another group regarding the importance of rehabilitation on young offenders compared with adults, and most respondent’s rates it as necessary (7.77), which is not quite high compared with the first group (ibid). Nevertheless, this rating is still high, even if it is not as strong as the first response. These findings are transferrable to the UK system, especially with various critics on the current Youth Justice System, such as Chambers et al., 2009, who argue based on the level of expenditure and ineffective policy-making. The public approval for rehabilitation efforts, therefore, starks in contrast to the government entities that desire to introduce deterrence efforts to 'get tough' on youth crime. From this knowledge, it is thus evident that the public supports the root cause of youth criminality and ascertains that a larger group of youth criminals will eventually go back to society. Besides, the public is well-informed that it is possible to address the youth's needs while still serving their sentences- or simply detain them without treatment and assume that they will be dissuaded from reoffending. Despite the above evidence, the main question emerges whether the general public general's faith is justified. Another debate, however, arises on the issue of custodial sentences. According to the New Economics Foundation (2010), custodial sentences are expensive; for instance, it costs the taxpayer an additional of £140,000 annually to secure a youth in protective custody. Besides, this is one of the approaches that do not seem to be working, according to the Independent Commission, (2010) 75% of youths on completion of custodial sentence proceed to offend the following year.

Custody should preserve its purpose of protecting the public from more austere and prolific youth offenders. Nevertheless, there is a wide range of alternatives and scientifically-verified practical approaches of dealing with several of the less severe offences for which custodial sentences would not be justified. Additionally, there are strong assertions for undertaking early interventions before criminal behaviour entrenches in a young person leading to a far-reaching contact with the criminal justice system (Smith, 2010).

Targeted efforts with YOTs with high rates of custody

Expansion efforts connected with regulation to assign the cost of safe remand to local establishments In 2013/14, the number of custodial clearances per thousand 10 to 17-year-olds (population) was 0.53. This number represents a 14% drop as compared with 2012/2013, and a drop of 35.6%, as compared with 2010/11 (UK Government, 2016). In 2013/14, the number of youths as defendants (10-17 years) who proceeded against in the courts was at 45,893. Out of this number, only 33,902 were sentenced for their crimes, the remaining were either found not guilty or had the charges against them plunged. Among those who were sentenced, 9,001 youths received first-tier sentences (i.e., fines and discharges), 22,675 received community sentences such as youth rehabilitation instructions. An insignificant number of teens (2,226) received immediate custody, which accounts for 6.6% of all sentenced young persons. In the period 2018/2019, the average jail sentence span offered to young people upsurges by more than six months since 2009 from 11.4 to 17.7 months. The ordinary jail sentence for criminals only offences was 14.5 months. The most popular form of custodial sentence offered among these young offenders was a custody and training order where 50 per cent of the time is usually served in supervision and the rest in the community on license and under YOT observation (Taylor, 2016). Concerning the children as victims of crime, a report that sought to uncover unreported crime among children shows that less than 20 per cent of young people and youths who suffer as victims from crimes such as theft and violence report this to authorities (APPG, 2014). These findings encompass the fact that kids and teenagers experience much higher crime rates than police ascertain and put it down as statistics. According to Muncie (2014), there are substantial crime rates and victimization among children and youth. Nearly 33% of children aged 11-17 years, for instance, report the crimes, especially violence in 2015.

How the system works

The YJB is an association of 230 personnel headquartered in London, and both have regional offices both in Wales and London. Within these regions the YJB is in charge of engaging the youths and to put them in remand or custody; oversee youth justice amenities; offering advisory services to the secretary of state for justice regarding the process of and guiding principles for the YJS; offering a safe facility for youths, safe teaching and training facilities and safe youth care home facilities’ rendering grants to local authorities among other bodies for the generation of plans that back its targets; contracting and dissemination of knowledge on preventing youth crimes (Souhami, 2015). Since 2014 the YJB's priorities have been reducing reoffending among young people, supporting the changing youth custody programmer, and delivering efficient practice in youth justice services. Various theories have been hypothesized describing the type of rehabilitative efforts to be employed for multiple types of offenders. For instance, the 'risk' theory involves the logic that offenders who are at greater risk of reoffending should have higher levels of rehabilitative efforts committed to them. In contrast, the lower risk offender should receive less devotion toward rehabilitative efforts. Besides, the needs principle involves the logic that criminogenic desires have to be besieged for change. According to Hannah-Moffat (2005), criminogenic needs include those risk factors that are perceived as unreliable or unpredictable. Some of these needs include antisocial perceptions and attitudes or negative peer associations. Inflexible risk attributes, including prior criminal records, are observably consistent. Additionally, the responsivity principle involves the usage of systems of treatment that are efficient and able to bring about the looked-for alterations in offenders and that are matched with offender learning styles (Bourgon & Gutierrez, 2012). However, this principle has received significant criticism from other authors for being circular since its definition is fundamentally the appropriate outcome (change in the offender). The primary debate, since creating this system is whether it is adequate to prevent or reduce youth crime and other antisocial behaviour. Several evaluations have been done or are currently being undertaken by various assessments to assess its effectiveness. Some of the earlier researchers found that among the non-institutionalized youth, rehabilitative undertakings had higher impacts on youths who had earlier combined offences (inclusive of offences against people) than teens who only had earlier crimes (inclusive of offences against people Loeber et al., 1999). For both traditional and non-institutionalized young people, there was a highly progressive treatment impact for longer rehabilitative durations. And in part of this move, this submission examines the current approaches and provides early suggestions of which strategies are or are not likely be to be fruitful. Besides, it suggests various rehabilitative strategies that could be employed to ensure there is no reoffending. Generally, the UK does not have a strong evidence base; in this regard, this submission draws evidence from abroad to increase understanding of what strategies work to prevent or lessen youth crime.

Methodology

This section discusses the methods used by the researcher in examining effective rehabilitation strategies among teenage offenders. This section will identify several contrasts and differences regarding rehabilitation strategies in various context and their impacts after implementation. The findings within the literature review ascertain that;

Crime can be prevented by addressing community needs by ensuring that people are provided with essential amenities, including healthcare, education and employment (Cullen, 2005).

Rehabilitation should address individual needs within the context of 'real life' or in the community (UK Government, 2016).

Policy-makers should be aware that rehabilitation efforts are not unfair practices in any way because the approach provides a delicate balance between addressing the needs of these youths and imposing sanctions that can be perceived as disproportionately punitive (Souhami, 2015).

In conclusion, there is a need to conduct further exploration to increase understanding of the effective strategies for rehabilitating youth criminals. This section will also consider previous researches cone through a meta-analysis on better rehabilitation strategies and other possible data collection methods, including survey and interviews.

Research Paradigms

This study was developed and undertaken to increase understanding of the effective rehabilitation strategies for youths engaged in criminal activities within setting X. The researcher used the qualitative inquiry, which entails the process of understanding a phenomenon based on distinct methodological traditions of review to examine a social problem. In this regard, the research develops a multifaceted and holistic image, analyses terminologies, and reports detailed perceptions of the participants and also undertaken in a natural setting (Denscombe, 2008). Since this research focused on a specific individual case, it could, therefore, be described as ideographic research which implies that the study will be interpreted and will result in different conclusions among different researchers. In the search for the best research paradigm for use in this study, a few previous methodologies of previous researches were examined, including Slade, (1991) and Pashler et al., (2008). In this regard, the issue of objectivity arose due to time and the limited number of research participants. Increased objectivity was thus attained by employing several research methods within the qualitative paradigm leading to effective implementation of data triangulation in this study. According to Denzin (2012), triangulation is commonly used in strengthening the study's validity. This process bases its idea that the researcher can confirm findings from one outlook of data collection through several data collection procedures. Triangulation, therefore, was attained via the application of various research methodologies such as meta-analysis with formal interviews.

Qualitative

The qualitative part of the study included an in-depth interview of the juveniles and the staff who provided contextual information for the research. Interviews with the parents also provided another dimension of understanding. The parents/guardians were the key figures in the children's lives while family life greatly impacted the child's development. Additionally, an interview with curriculum leadership team was done to conclude on effective rehabilitation strategies for juvenile offenders.

Possible data collection methods

Questionnaire and interviews

Final data collection methodology will be questionnaires and interviews. The researcher developed three five-question surveys for the participants, staff within the institution, the curriculum leadership experts, and parents. After which the researcher sent out the copies to these people within one week. Before sending these questionnaires, the researcher conducted a pilot test with 15 of the participants to determine if the process would be useful. After which, it was decided that the researcher would clarify the questions during the interview process. Among the sample population in this exercise were mostly female, mostly white or of mixed ethnicity. The average age was between 13- 17. Most of the participants had earlier convictions. Also, nearly one-third of the participants had a history of aggressive behaviour. Some of the interventions examined included counselling, skill-oriented programs and combined services (a combination of several treatments that encompass various diverse approaches), and community residential programs.

Secondary Data

Secondary data involved a meta-analysis from a pool of studies selected from a meta-analytic database, including Scopus, PubMed, JSTOR, and Google Scholar. These databases were found to contain relevant sources, reliable and quality sources. According to Balshem et al., (2011), works of literature should be quality and pertinent to conclude on high-quality information. In several samples of the study, juveniles were under the juvenile justice system supervision and were under court-ordered interventions. The study used meta-analysis and systematic review of several studies, mostly those with small samples and conflicting results to conclude this research. According to Bloomberg & Volpe, (2008) meta-analysis involves a set of techniques employed to extract the findings of several different works of literature into one report to create an individual and more accurate assessment of an impact. In this regard, the objective of meta-analysis is to heighten the statistic strength and manage controversy among individual studies when they conflict with each other to enhance estimations of the effect's size and to answer to the generated questions not previously modelled in component researches (Schmidt & Hunter, 1999). All these descriptions accentuate that there is a necessity of combining the studies, according to Egger et al., (2002), most researchers always have the temptation of combining studies even though such procedure sometimes seems to be inappropriate or questionable. In this regard, although meta-analysis usage in studies is increasing, it has several detractors such as when poorly designed, it could produce wrong statistics that could be misleading. Besides, the bias in the inclusion and exclusion criteria could interfere with the effectiveness of meta-analysis. Bloomberg & Volpe, (2008) identify two types of biases that could arise from inconsistencies in the exclusion and inclusion criteria. Spectrum Bias- this inconsistency arises from publication bias and findings reporting bias, which has implications for review. Bias in the selection of literature could overlap with these biases. For instance, the bias in the identification of studies could overlap with these biases. Random error is another error resulting from individual mistakes in reading and reviewing works of literature. Even if the author and the reviewers have a mutual understanding of the selection benchmarks, such misunderstandings could arise individually. Another risk of yielding unsatisfactory results include when the author ignores heterogeneity in the literature search process. Another weakness in using meta-analysis is that the procedure can only give data on the characteristics and the effectiveness of earlier and present programs. However, this research design, for instance, enables the researchers to amass information from several works of literature that could be too small by themselves to provide firm conclusions. To avoid the risk of bias and render the meta-analysis process ineffective, the author clearly described the inclusion and exclusion criteria in detail sufficient enough to preclude inconsistent submission in literature search and selection.

Meta-analyses have opened doors to information more especially yielding a great deal of information regarding various gaps in knowledge; however, careful usage of this process, especially in reducing forms of bias, could lead to trustworthy evidence.

Critiquing tool

The structured critique approach was used for all the sources of evidence in this study. Besides, the author also used a systematic evaluation of the literature identified to conclude the arguments presented in the study. A structured critique strategy allowed the researcher to ascertain weaknesses and strengths for every work of literature selected for this study. Specifically, the author assessed the research questions and objectives of every literature. The research design of the literature was also determined to find whether they were suitable (Aveyard, 2010).

Main themes

The study’s primary themes included effective rehabilitation strategies in the UK for youths in criminal activities and what successful rehabilitation programs look like. In the results section, terminologies linked with crime prevention strategies such as custody or probation were employed in the search results section of the search. These terms were put in the youth's perspective of recovering from rehabilitative programs and never to engage in reoffending behaviours.

Data extraction and Synthesis of Findings

Data were extracted from the various studies to conclude this report. The primary information included the names of authors, the year of publication, the forms of reviews (either quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods), the research objectives, the research design, the ethical considerations, and the findings. The studies were ranked based on their trustworthiness assessed through their research designs and the quality of their evidence. The hierarchy of evidence enables authors to grade the studies based on their strengths and weaknesses. Synthesis of the findings employed a narrative approach that focused on data interpretation of the results. This study was based on the post-positivist configuration (LoBiondo-Wood & Haber, 2014); a qualitative approach, on the other hand, pursues to examine the occurrences emphasized in the people's experiences. The summary of the findings was provided by comparing the differences and features of the body of pieces of evidence.

Issues of trustworthiness

The issue of trustworthiness includes the rigour of the study and its confidence in the findings. It also encompasses the methods employed in the study. As mentioned in the research design section, this study's trustworthiness mainly relied on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. This process, therefore, determined the kind of evidence to be used for this research. In this regard, the author documented the inclusion criteria in a protocol- the criteria were set with a line of reasoning and arguments and developed on the analytic structure. The advantages of utilizing a protocol approach include improving the transparency and rigour of the research process and reducing bias in the study selection determinations. Another aspect that poses trustworthiness concern is ambiguity in the inclusion and exclusion criteria. More significant ambiguity in the selection criteria increases the capability of poor reproducibility because of several subjective decisions involving what should be included, potentially resulting in the random error, at least in the process. To reduce these multiple variations and thus ambiguity, the author identified the outcomes, any limitations on measurement techniques and offered guidelines for handling of composite results. All these measures should accompany the selection criteria. Besides, in efforts to reduce the risk of inconsistency in the study selection, the author planned on how to handle this variation early enough in the search process. Another issue of trustworthiness is the lack of specificity on factors of outcome measurement, which could cause bias in the study's conclusions. For instance, the inclusion criteria could not adequately specify the relative significance of varied time points for outcome measurements. This instance could lead to vital variations in conclusions regarding what outcome point pair are identified for inclusion, especially in a meta-analysis.

Ethical Issues

Informed consent

While completing a practitioner-based study, a researcher should consider consent and permission for a study to meet ethical guidelines (Powell & Smith, 2006). As highlighted earlier in the introduction section, the issue of consent has been widely debated among several authors, including Creswell & Clark, (2017) and also after the release of the Rochford review (2016). The child participants (below 18 years) in this case are considered as vulnerable because of their age and relationships with practitioners with the researcher who provide care. However, adult participants (over 18 years) will have to give fully informed consent individually. Even though consent was required from parents in the former group and fully informed consent from the latter groups, permission to conduct the research was sought from setting X’s authorities. The parents were given with a letter detailing the nature of the study and the right to withdraw their consent at any time during the study.

Reporting and publishing of research findings

Some of the ethical considerations of this study involve the process of reporting and publishing the findings. In this regard, the author ensured that data was not fabricated by presenting findings of the reviewed studies as they were. Besides, the author corrected any errors when they were found, did not plagiarize work belonging to others, did not publish evidence more than once, assigned authorship credit appropriately, and shared information with others for verification purposes. Secondly, the lack of methodological rigour also raised ethical considerations with this research. However, the author researched with precision by itemizing the various procedures involved. For instance, the process required collection, summarizing, and integrating vast amounts of information. The author made sure that each step was done correctly; the author invited expertise to review the process and also suggest any ethical breach. This study did not have institutional review boards to convince that the advantages of the research of the findings balance the risks. Besides, the study used public documents; informed consent and confidentiality was not an issue since the information cannot be deceived or maltreated (Cooper & Dent, 2011). This allowed the researcher to implement various measures to ensure that the research complied with various ethical guidelines in research. According to Wilson & Neville (2009), while completing a qualitative study, the researcher should have an in-depth understanding of the integrity of the survey. Besides, the researcher should ensure enough data has been collected to draw appropriate conclusions and be open to the research's limitations.

Limitations of the study

Not all variables for the selected studies were comparable; therefore, the author needed to construct new variables that proved similar; this restricted the analysis to shared components. Secondly, this study relied on subjectivity rather than objectivity, just like any other meta-analysis study. Most of the analysis, such as narrative reviews, contained subjective decisions to conclude. Nevertheless, such decisions were explicitly expressed in the survey. Lastly, this study deals only with the significant effects which prove to be worthy of being generalized to the target population; nevertheless, the impacts of interaction might also be investigated by moderator analysis, which was not done.

References

- Allen, G. (2011). Early intervention: the next steps, an independent report to Her Majesty's government by Graham Allen MP. The Stationery Office.

- Barber, J., & Doob, A. (2004). An analysis of public support for severity and proportionality in the sentencing of youthful offenders. Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice, 46(3), 327-342.

- Bloomberg, L. D., & Volpe, M. (2008). Presenting methodology and research approach. Completing your qualitative dissertation: A roadmap from beginning to end, 65-93.

- Bonta, J., & Andrews, D. (2010). Viewing offender assessment and rehabilitation through the lens of the risk-need-responsivity model. Offender supervision: New directions in theory, research and practice, 19-40.

- Čehajić-Clancy, S., Effron, D. A., Halperin, E., Liberman, V., & Ross, L. D. (2011). Affirmation, acknowledgment of in-group responsibility, group-based guilt, and support for reparative measures. Journal of personality and social psychology, 101(2), 256.

- Chambers, J. C., Yiend, J., Barrett, B., Burns, T., Doll, H., Fazel, S., ... & Sutton, L. (2009). Outcome measures used in forensic mental health research: a structured review. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 19(1), 9-27.

- Cooper, H., & Dent, A. (2011). Ethical issues in the conduct and reporting of meta-analysis. Multivariate applications series. Handbook of ethics in quantitative methodology, 417-443.

- Creswell, J. W., & Clark, V. L. P. (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Sage publications.

- Denscombe, M. (2008). Communities of practice: A research paradigm for the mixed methods approach. Journal of mixed methods research, 2(3), 270-283.

- Goldson, B., & Muncie, J. (2009). Youth justice (pp. 257-278). Oxford University Press.

- Lab, S. P., & Whitehead, J. T. (1990). From “nothing works” to “the appropriate works”: The latest stop on the search for the secular grail. Criminology, 28(3), 405-418.

- Lahey, B. B., Gordon, R. A., Loeber, R., Stouthamer-Loeber, M., & Farrington, D. P. (1999). Boys who join gangs: A prospective study of predictors of first gang entry. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 27(4), 261-276.

- LoBiondo-Wood, G., & Haber, J. (2014). Reliability and validity. Nursing research. Methods and critical appraisal for evidence based practice, 289-309.

- Menon, A., Korner-Bitensky, N., Kastner, M., McKibbon, K., & Straus, S. (2009). Strategies for rehabilitation professionals to move evidence-based knowledge into practice: a systematic review. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 41(13), 1024-1032.

- Nagin, D. S., Rosenfeld, R., Quinet, K., & Garcia, C. (2012). Imprisonment and Crime Control: Building Evidence Based Policy. Contemporary Issues in Criminological Theory and Research, 309-16.

- Powell, M. A., & Smith, A. B. (2006). Ethical guidelines for research with children: A review of current research ethics documentation in New Zealand. Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online, 1(2), 125-138.

- Powell, M. A., & Smith, A. B. (2006). Ethical guidelines for research with children: A review of current research ethics documentation in New Zealand. Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online, 1(2), 125-138.

- Slade, S. (1991). Case-based reasoning: A research paradigm. AI magazine, 12(1), 42-42.

- Smith, R. (2011). A New Response to Youth Crime, David J. Smith (ed.), Cullompton, Willan Publishing, 2010, pp. 424, ISBN 978 1 84392 754 9 (pb),£ 27.50.

- Souhami, A. (2015). Creating the Youth Justice Board: Policy and policy making in English and Welsh youth justice. Criminology & Criminal Justice, 15(2), 152-168.

- Spinhoven, P., Klein, N., Kennis, M., Cramer, A. O., Siegle, G., Cuijpers, P., ... & Bockting, C. L. (2018). The effects of cognitive-behavior therapy for depression on repetitive negative thinking: A meta-analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 106, 71-85.

- Williams, L. R., & Steinberg, L. (2011). Reciprocal relations between parenting and adjustment in a sample of juvenile offenders. Child development, 82(2), 633-645.

- Wilson, D., & Neville, S. (2009). Culturally safe research with vulnerable populations. Contemporary Nurse, 33(1), 69-79.

- Wormith, J. S., Althouse, R., Simpson, M., Reitzel, L. R., Fagan, T. J., & Morgan, R. D. (2007). The rehabilitation and reintegration of offenders: The current landscape and some future directions for correctional psychology. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 34(7), 879-892.

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts