The Role of Charity in the UK

Chapter One

1.0 Introduction

For many years, charity work has been an essential element of the UK society, and many charity organizations depend on the continued emergence of charity workers (Howlett, 2008). According to Hurley et al. (2008), various charity organizations provide services to a variety of social development sectors including blood donation banks, hospitals, sports, emergency rescue, animal rescue as well as education and knowledge transfer. In fact, the role that charity work plays in the societal well-being warranted a declaration of ‘year of charity work in 2001 by the United Nations (Kay & Bradbury, 2009).It is therefore not surprising that the UK is home to some of the largest charity organizations in the world (Hurley et al, 2008), given the high regard awarded to charity work around the world.

The United Nations (2001) defined charity work as the services delivered by individuals as non-career, non-profit, or non-wage oriented contributions towards the well-being of the society. Ideally, this definition covers a variety of self-help actions and collective initiatives made by individuals to address the economic, social, cultural, and humanitarian well-being of others in the community. Nonetheless, Low et al. (2007) observed that in the UK, charity work is perceived as a ‘selfless’ delivery care services to others without demanding or expecting a payment and that these services are often offered by the privileged to the less privileged. Furthermore, Milligan & Fyfe (2005) observe that charity has partly been viewed as a social service that gets compensated for through other benefits such as stipends, training, and access to learning or employment opportunities.

A debate has emerged regarding remuneration as a contrary activity in charity work. According to Schuurman (2013), some researchers opine that charity workers should be awarded some incentives in the form of educational credits, recognition, and awards, as well as skills acquisition. These forms of awards, as argued by Schuurman (2013), occur in kind and do not represent financial remunerations. Earlier research has identified different kinds of charity workers, namely service charity workers, self-interest charity workers, consummatory charity workers, and public advocacy charity workers. According to Milligan & Fyfe (2005), service charity workers work in organizations that offer direct help to others through caregiving, teaching, or mentoring. The work of social charity workers is fundamentally based on the philanthropic approach, which is commonly driven by cultural and religious traditions (Patel et al. 2007). The second category of charity workers, public advocacy charity workers, are individuals who take a broader approach to economic and social challenges facing their target groups – thereby basing their work on the social justice approach (Patel et al. 2007). On the other hand, consummatory charity workers integrate their charity activities with enjoyment, fellowship, while self-expressive charity workers use charity work to advance their economic or occupational development (Ziemek, 2006). Having explored various types of charity workers, a significant question that remains mostly unanswered according to the author’s opinion is: why do people choose to be charity workers even at the expense of their well-being? The main aim of this study is to explore the social motives of charity workers.

1.2 Research Aim

To examine the experiences of charity work among workers charity organizations

1.3 Research objectives

To identify people’s motives for charity work

To identify challenges faced by charity workers in charity organizations

To explore the coping strategies of charity workers working in charity organizations

To identify the impact of charity work on the workers and service recipients

1.4 Research Questions

Why do people choose to be charity workers?

What are the challenges facing charity workers who work in charity organizations?

What are the coping strategies for charity workers working in charity organizations?

What are the impact of charity work on the workers and service recipients?

1.5 Justification of the Study

There is a culture of charity work in the UK, even though little research has been done on this topic within the Kingdom. It is one of the civil service activities within the sphere of UK democracy, which has been experienced since the 1960s (Howlett, 2008). Statistics released by UK Civil Society Almanac (2019) indicate that in the past one year (2017/2018), there were at least 20.1 million charity workers in UK groups, organizations, or clubs. Furthermore, according to UK Civil Society Almanac (2019), 22% of people in the UK were regularly engaged in formal charity work; totaling to 11.9 million people – while informal charity work had a prevalence of 53% in 2017/2018. These statistical trends indicate the prevalent nature of charity work in the UK and the need for better research focus on charity work as an item of public interest. Moreover, charity work provides an opportunity for people to bring positive change within their society. According to Schuurman (2013), this change is not only for the benefit of the charity workers but also for other members of the communities within which they execute their charity work. There is a shortage of literature regarding charity work in the UK in spite of many charity organizations in the UK. Furthermore, to the best of the author’s knowledge, only a few charitable organizations in the UK evaluate the quality of service delivery in the realm of tight schedules such organizations operate on (Bussel & Forbes 2002). Based on these observations, inform the need for further research on charity and charitable organizations in the UK. Ideally, the findings of this study will be a source of knowledge to academic institutions, participants in the UK Non-governmental Organizations (NGOs) as well as other organizations involved charity work. As a source of knowledge, this study will provide appropriate support structures to maintain their staff.

Chapter 2

2.0 Literature Review

This section explores existing knowledge on charity work as well as the theoretical approaches to charity work – mainly indicating the main reasons why people join charity work. It will also highlight existing knowledge about the strategies of retaining and developing the commitment of charity workers. One of the main aims of charity organizations is to provide solutions to various societal problems through group or individual actions (Low et al., 2007). Charity is an institution of many western countries, including the UK, at least based on the statistics mentioned above. Generally, charity workers engage in activities of community development, including rehabilitation, economic development, human right, peace, cultural integration, and employment (Peter, 2005). Furthermore, according to Schuurman (2013), contemporary society engages in many charity activities not only for purposes of personal growth but also for the well-being of the people they deliver the services to. Incidentally, this growth surpasses the individual charity worker’s level and extends towards community development through citizen participation. Hence, according to Milligan & Fyfe (2005), charity work is a stable phenomenon that occurs continuously and is deeply rooted in the community. The direction of UK charity work generally relies on the Kingdom’s socio-economic status, cultural dimensions, and the political environment, which further give meaning to charity work (Perold et al., 2006). Having established that at least 20.1 million people in the UK were involved in charity work in the past one year, it is possible to extrapolate that the social and economic situations faced by various members of the UK society set the context for charity work by determining who the charity workers are. Researchers (e.g., Ziemek, 2006) also argue that charity workers have a better chance of being employed by charity organizations because it is a sign to the employer that the charity workers can take the initiative regardless of not being paid.

Continue your exploration of What Way Do University Students Perceive The Role Of Their Ethnicity Influencing with our related content.

2.1 Global Perspectives of Charity work

Literature by Brussels & Forbes (2002) indicates that charity work is influenced mainly by social identities such as age, gender, education levels, socio-economic status, as well as other social aspects such as marital status and personality. With regards to education levels, there is conflicting evidence on how people’s academic qualifications may influence their decision to engage in charity. For instance, Haski-Laventhal (2007) argued that the more educated or skilled a person is, the more likely that they will engage in charity. Furthermore, research by Haski-Laventhal (2007) on charity work within the Northern Hemisphere region revealed that (80%) charity work in that region is dominated by the white middle-class population who are highly educated and skilled. Haski-Laventhal (2007) found that more than a half of these populations have various levels of academic qualifications including degrees, and Doctorates, live in urban areas, have large volumes of assets and fund multiple charity organizations. Considering the current trend of charity work in the UK, it is possible to extrapolate that the same characteristics apply to most charity workers in the UK. With regards to specific ethnicities, Haski-Laventhal (2007) found that among the charity worker’s population in the Northern Hemisphere nations, 20% represented the black community, 10% represented Hispanics while 5% represented other communities. Conversely, in a literature review study by Schuurman (2013), it was found that adults and youths from low socio-economic backgrounds with a quality education also participate in various community programs, schools, and churches.

2.2 Socio-Economic Status

Existing research has also found a correlation between poverty and charity work. For instance, a previous South African study by Perold et al. (2006) found that poor people were more likely (23%) to do charity work than those with better socio-economic status (17%). Similar findings were made by Nattras & Seeking (2003), who revealed that people in the middle class less often engage in charity work.

2.3 Gender

Existing research also reveal gender as another factor that influences people’s ability and desire to participate in charity. For instance, the feminization of charity work is a widespread global phenomenon, and the difference between male and female charity work only tend to emerge where the charity activity is more physical or riskier (Schuurman, 2013). Furthermore, Karen & Mandeep (2004) found an element of racialization and familiarisation of people working in charity organizations. Notably, women were found to be more (19%) than men (17%) while women gave more time to their charity work that men (i.e., 12 hours and 10 hours respectively). Additionally, Karen & Mandeep (2004) found that women tend to be more nurturing and emotive in their charity roles than males. Several other studies have also found similar results. For example, Marincowitz (2004), in a survey of home-based HIV/AIDS charity care programs, found that women were more likely to do charity than men, and were come committed in their charity work that their male counterparts. However, in another study by Crook et al. (2006), women were found to be more likely to be committed in their charity work if they had alternative sources of income i.e., if their spouses were breadwinners.

2.4 Perceived Benefits and Challenges of Charity work

Existing literature shows evidence of various challenges and benefits derived from charity work. For example, Kiviniemi et al. (2002) found that regardless of their age, socio-economic class, or gender, most charity workers act as good role models in their jobs. Similar results were found by Boyle et al. (2006) & Ritcher & Morrell (2006), who found that lack of male role models in the society, has contributed to a shortage in socializing young children. However, Scileppi et al. (2000) found that despite the various motives (e.g., social prestige, or just doing a favour to the organization) held by charity workers towards charity work, most charity workers are driven by personal satisfaction. Moreover, Bergers (2006) argued that charity workers tend to have large social networks because they are more likely to create new friends, develop new relationships with the program organizers and find a meaning to the particular charity work in which they engage. A body of literature shows that charity workers gain more responsibilities as they advance in their charity careers. They create more opportunity to learn decision-making skills as well as skills in leadership, policy-making, and financial budgeting as they take up new roles in charity organizations (Vecina & Davila, 2006). Moreover, Scileppi et al. (2000) argue that the sense of being essential contributors to people’s lives makes charity work even more fulfilling – mainly because that their charity work contributes to the mobilization of scarce resources to the needy ones. Nonetheless, literature has documented various disadvantages of charity work that are worth noting. For instance, Kiviniemi et al. (2002) observed that charity workers are more likely to experience burnout, especially when they are dealing with physically and mentally demanding tasks. Some scholars (e.g., Karen & Mandeep 2004) propose that most charity workers have unmet needs because the government leaves most of its responsibilities to charity organizations, overburdening them while awarding the charity workers little powers and resources.

Furthermore, Dekker & Halman (2003) claim that the high engagement levels experienced by charity workers make them lose touch with the people in need of their services may be perceived as patronizing and tend to and may not deliver quality services with poor program coordination.

2.5 Theoretical Framework

Researches have attempted to understand charity work from a variety of theoretical perspectives, namely the developmental theory, the role identity theory, and t ecological theory. However, due to inadequate space, this study will focus on the role identity theory to help in understanding the people’s motivations for engagement in charity.

2.6 The Role Identity Theory

Stryker (1968) defined the role identity theory as a theory that relates identities to role-related behavior and role relationships of people. Ideally, according to Stryker & Burke (2000), believers in this theory suggest that people are made up of many identities and that these identities are influenced by the environment or contexts within which they live. In short, they believe that the various roles individuals take in society give them a sense of identity. Therefore, an individual’s identity may remain constant or change to provide them with role identities or just identities. A typical example given by Schuurman (2013) is how gender or one’s occupation identities influence their behaviour. But other scholars who believe in this theory argue that people tend to organize their role identities in hierarchies, either mentally or internally. For example, Burke & Reitzes (1968) explained that people would give more attention to the highest-ranked role. Also referred to as the identity salience, the identity role hierarchy influences people’s efforts towards the tasks they perform. As people gain more experience in certain role-identities, they begin to think and perceive themselves in terms of those role-identities. They reflect their role perceptions, develop higher self-definition, and develop some the view that those identity-roles are significant to their lives. Individuals may then behave in relation to their role identities. And the more critical they perceive their role identities to be, the more likely they are to act in consistency with such identities (Hongwen et al., 1988). In short, a perception of their role identity is a good predictor of their behavior. According to Schuurman (2013), the concept of role identity is especially generative in understanding how role identities and the perception that they are important influences to the level of efforts and commitment put by individuals on some roles, and how well these roles are performed. Some of the significant contributors to this theory (e.g., Stryker 1968) argue that people organize their identities in hierarchies of importance, and the role identities ranked highest are given more attention and effort than those ranked lowest. Furthermore, the theorist believes that people are more likely to invoke the highest-ranking role-identities in situations that involve different aspects of the self. This theory is especially helpful in the understanding of why charity workers are perceived as role models in society. It gives insights into the changing nature of identity in people’s lifespan and enables the knowledge of both inside and outside aspects of an individual’s charity work behavior.

Chapter Three

3.0 Research Methodology

3.1 Research Design

This study adopted a qualitative research design, which has had a significant recognition in social sciences research. Ideally, a qualitative research design was taken so that the researcher could gain a better understanding of the concept of charity work and more importantly, the factors that motivate people to participate in charity organizations. The use of a case study is mainly chosen to allow the researcher to extrapolate what is happening in a single case. Ideally, according to Apan et al. (2012), the case study approach provides credibility and a chance to optimize the results by triangulating the interpretations and descriptions of various data collection methods (i.e., primary and secondary data). Furthermore, the qualitative research design adopted within the context of single case study enables the researcher to take advantage of the respondents’ experiential knowledge and the influence of such knowledge on other contexts (Bloor & Wood, 2006). Besides, the qualitative research design applies a phenomenological interpretive philosophy, which enables the researcher to questions how this experience is of importance to the people experiencing it (Given, 2008). Moreover, according to Gisselle et al. (2018), the phenomenological interpretive philosophy questions the factors triggering human acts. Therefore, because the current study seeks to understand the motivations and experiences of charity workers in charity organizations, the phenomenological interpretive philosophy emerges to be the most suitable. The study relied on in-depth interviews to collect data because these methods can develop rich descriptive data that would otherwise not be accessible through quantitative research design. Moreover, the qualitative research design would allow the researcher to record autobiographical accounts of the participants (Apan et al, 2012), making the data richer and more diverse.

3.2 Study Sample

The study was conducted at X organization. The researcher sought written permission from the organization’s management to allow the conduction of the research (Appendix 1). Respondents were selected based on two primary criteria, mainly because both participants and key informants were required. On the one hand, participants were charity workers who had a good track record in the organization and had an experience of 1 to 5 years, although not part of the management, the board of staffs. On the other hand, the key informants were those who had worked in the organization for the past five years and were either part of the staff, board, or managers. The researcher sought a registry from the organization to determine people who fit these two criteria. The charity workers were then called, physically approached, or emailed about the study and recruited during the organization’s regular training session. A purposive sample method was adopted to select a representative sample of the target population (Apan et al. 2012) because the participants had to meet the selection criteria. Initially, a sample of seven participants was selected. The researcher obtained consent forms from the ten selected participants, who attended a briefing about the study before the interviews could start. All the selected participants completed the interviews with no attrition.

3.3 Data Collection

There are various techniques through which qualitative data can be collected. According to Apan et al. (2012), the methods often vary with the discipline although they are generally meant collect data on the life experiences of the target population and the implication of these experiences from their own experiences. There are a variety of methods used to collect data depending on the purpose of the study (Gisselle et al. 2018) and the target sample (Bloor & Wood, 2006), but the data can be collected in various formats including audio, paper, photographic and video (Gisselle et al. 2018). In the current study, the researcher relied on tape recording as the method of data collection, after which the data were transcribed in verbatim to develop written data. The researcher also used semi-structured interviews to collect data from both the key informants and the general participants. The key informant participants were those with managerial roles, board members, and coordinators who had an experience of more than five years in their respective roles. Apart from the interview guides (attached in appendix 2 and 4), the researcher also provided an opportunity for autobiographical accounts to add richness to the interview data. Nonetheless, the researcher also conducted participant observation at the respective organization before the interview sessions to observe the charity workers on an ongoing basis to validate the interview data. Generally, the data collection methodologies were coordinated to gather the best of respondent’s phenomenology of lived experience, thereby proving the study’s theoretical perspective so that rich data was collected. As opposed to quantitative approaches that do not make use of stories for data collection, qualitative methods use interpretive research paradigm to enable the respondents to speak their voice and provide a detailed description of their experiences of a situation (Apan et al. 2012). Therefore, semi-structured interviews thus enable the collection of more in-depth data compared to other data collection methods since they are flexible and allow for probing (Bloor & Wood, 2006). Furthermore, according to Gisselle et al. (2018), semi-structured interviews allow participants to control the flow of the discussion and encouraged to explain their responses in a manner that provides more abundant data. The semi-structured interviews conducted in the current study aimed at understanding the respondents’ perspectives about their experiences as charity workers, thereby highlighting the importance of expression and content.

3.4 Data Analysis

The researcher analyzed the qualitative data during the process of data collection because the interviewees continuously reflected on their relationships, connections, and impressions. Hence, the researcher found an interpretive phenomenological analysis (Gisselle et al. 2018) useful in evaluating the essence and experience of the interviewees during the interview sessions. The researcher then applied the analysis to the transcribed data before reading and dividing the data into smaller units. Thus, the researcher used an inductive approach to divide the smaller units of data emerging from the text into themes (Bloor & Wood, 2006). Besides, the themes were identified as they emerged from the interview text. Next, the researcher used open coding to group the data and develop coherent ideas from the transcribed text (Bloor & Wood, 2006). The researcher then linked the themes to supportive extracts, which were then used to communicate and describe the participant’s experiences (Given, 2008).

3.5 Validity and Reliability of the Study

The data from semi-structured interviews were triangulated with the researcher’s observation to enhance the reliability and to contextualize the interviewees’ perspectives. Moreover, the researcher used observed data to validate and confirm the authenticity of the study findings because the researcher confirmed that the experiences described by the participants were similar to the made observations. According to Gisselle et al. (2018), this type of multi-faceted data collection is comparable to a case study approach that produces in-depth data and evidence.

3.6 Ethical Considerations

Having been a charity worker at an NGO, the researcher had easier access to participants and was assured of their commitment to participate. Moreover, permission was sought from the organization’s director and head of research, who gave their consent for the study. The researcher also submitted a research proposal to the university ethics committee for ethics approval before proceeding with the study. Besides, the researcher sought informed consent from the participants before engaging them in the study. Their participants were also assured of their right to confidentiality and the right to withdraw from the study as per their wish.

3.7 Research Reflexivity

Interpretive inquiries hold high regard for research reflexivity because the researcher is the main instrument of investigation, including data collection and analysis. Therefore, it is useful for the researcher to give an account of how they are related to the field of study, their social background, political, and theoretical inclinations that may influence the study outcomes. According to Gisselle et al. (2018), developing a robust self-reflection requires the researcher to understand themselves and their role in the study, thereby understanding their advantages and disadvantages of to the study. The researcher was in charity work for the past ten years in semi-urban communities and had their share of experiences of charity, which acts as a motivating factor to this study topic. Having been a charity worker before, the nature of the current study does not allow the researcher to be utterly objective because the researcher can identify with the roles and experiences of a charity worker. Therefore, the researcher has been exposed to, and understands the experiences, benefits, and challenges of charity in various levels and capacities. However, this experience can be of great interest to the study as it can enhance the general trust and transparency of the study. Besides, the results presented in the current study only reflect the participants’ experiences in their own words and not subject to the researcher’s influence. Moreover, the supervisor regularly checked the researcher’s interpretation of the data to ensure that it was as objective as possible.

Chapter 4

4.0 Results

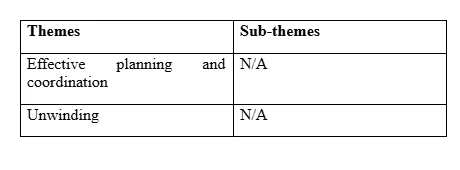

14 themes and 2 sub-themes were developed from the interview results as illustrated in the table below (table 1). This chapter discusses these themes and sub themes illustrated with the extracts of respondent quotes.

Question 1: Why do people choose to work in charities?

Question 2: What are the challenges facing charity workers in charity organizations?

Question 3: What are the coping strategies for charity workers working in charity organizations?

Question 4: What are the impact of charity work on the workers and service recipients?

Question 1: Why do people choose to work in charities?

A majority of participants mentions personal beliefs and preferences as the main motivation to involvement in charity work. While some had a string belief in human rights and the need to preserve them through charity work, others just joined charities to satisfy their passion. For example, participant 1noted that “…the reason I got into advocacy is I believe that people should have rights….” also, participant 6 said that: ….So, that was 2002 and I've been here since then because I enjoy the work…..while participant 7 described that:”….But I think what sort of drew me to that once I knew what the job role was because it was mental health…”

Moreover, some respondents joined charity organization due to the need to create a meaningful difference in other people’s lives. For instance participant 1 noted that “….I wanted to do something more meaningful. I was tired of being a chef and working in private, public sector. It was meaningless. So, I wanted to do something a bit more meaningful to benefit other people rather than some capitalist organization”

Another important motivation to people’s involvement in charity, as identified in the interview responses is a feeling of necessity to address challenges experienced through family and friends. Hence, some respondents felt motivated to join charity organization in response to whet their had experienced among their family and friends. For example, according to participant 4, “…I think, because I had some issues and family members had some issue mental health problems and long-term conditions. So, going through that made me feel like I want to do something to help people…” Besides, participant 3 said that “…initially, 30 years ago, it was a mental health charity because my best friend committed suicide. So, I wanted to reach out to people who were probably hiding their mental health difficulties a bit...”

Lastly, an important motivation to joining charity organizations is unemployment. One respondent narrated that they joined a charity organization when they were jobless, and therefore joined charity work with hopes that they would end up employed. For example, respondent 2 said that: “…I was just unemployed myself actually and I went to somewhere which was a bit rundown and I just thought I make an effort to, you know, listen to what they're saying to me, put aside a judgment I've got…”

Question 2: What are the challenges facing charity workers in charity organizations?

Motivation

The analysis revealed various challenges experienced by workers in charity organization. For instance some respondents reported a loss of motivation to work in charities after some years in the organization. For instance Respondent 1 noted that: “…It doesn’t make me as fulfilled as it used to. I guess not so much these days..” while respondent 5 said that: “…Sometimes you will go away and feel like you could have done something else, you could have done that better…”

Inadequate Resources

Lack of financial resources to drive the charity programs emerged as one of the major challenges experienced by charity workers in charity organizations. The respondents complained that inadequate financial resources not only hindered the program implementation but also killed their motivation to deliver quality work. For instance, respondent 2 noted that: “…They wouldn't necessarily have more money to support people for example. I think they'd be under more pressure because they got many people and often, they don't get so much attention…” Similarly, respondent 4 said that: “…You know, for instance, funding is always an issue, resources are always an issue...” Similar remarks were made by both respondent 6 and respondent 5.

Heavy Workloads

It also emerged that workers in charity organization face the challenge of heavy workloads and overdependence from the clients. This led to overwhelming tasks as well as burnout. For instance, respondent 3 said that: “…Yeah, because some people will become very dependent on you. Despite your best efforts to get them to stand on their own feet they will keep coming back, because they've got that connection with you…” Similarly, respondent 4 complained that: “…And sometimes you can get too involved in a case and end up burning out…”

Negative Client Perception

Some respondents acknowledged the challenge of clients holding a negative perception towards them despite their efforts to serve and improve the lives of their clients. For instance, respondent 3 complained that: “…they then might take that the wrong way and say `well, you don't support me anymore, you're rubbish` .So there's a downside where they could complain when you want to end the case but they praise you when you're working with the case…,” while respondent 3 noted that: “…Sometimes you get a little bit resentful, because you're not, you know, you don't feel that you're valued…”

Lack of support

The last challenge identified by the respondents is lack of support and inadequate teamwork which hinders coordination and delivery of quality services to clients. For instance, respondent 7 complained that: “…the most frustrating challenge is trying to get in touch with people like social workers, or, you know, chasing the safeguarding team or getting the right information, getting all the information..”

Question 3: What are the coping strategies for charity workers working in charity organizations?

Effective action plans

Some of the coping strategies used by the interviewed charity workers to address the said challenges include effective case by case planning characterized by prior development of program action plans to ensure an organized implementation. For instance, respondent 1 said that: I think I am able to balance things. I think sometimes that's hard I have to say, depending on the case and the number of cases and the number of difficult cases and what's going on at the time in. I guess it depends on what's going on at home as well, and “… I think you could run a whole charity project without seeing one person if you just make all the notes and numbers and make everyone up…”

When the respondents were asked about the strategies they use to ensure a proper work-life balance, they noted spending time with family and taking a break from office work as some of the most effective strategies. For example, respondent 3 said that: “…I don’t take my work home with me. I have got a very lovely partner and we have a very nice private life and nice group of friends…” while respondent 4 said that: “…what do I need to do to make sure that I'm not working too much so that it just doesn't make me ineffective in my job role…”

Question 3: What are the impact of charity work on the workers and service recipients?

Personal Development

When respondents were asked whether their involvement in charity work had any impact on them r one the lives of their clients, they identified various impacts that could be categorized as impacts on charity workers, and impact on the clients:

Impact on Charity Workers

The respondent acknowledged that involving in charity work enabled them gain more experience in their respective specialties as well as an improvement in their social lives. With respect to the former, respondent 2 said that “…Well it's really, it's great I must say like I said didn't really know that these charities did this kind of work, so it's opened my eyes to those charities, and you know to the other people working there as well…” and that “…What is very moving is how people contribute to each other…” Moreover, the respondents acknowledge the important role that charity work contributed to their personal satisfaction. For instance, respondent 3 said that: It makes me feel good and grateful that I help people and make them see things in a different way. I feel I empower people. It makes me feel like I have earned my money and I haven’t just sat there with my feet up; I have actually helped someone to turn their life around…” Moreover, respondent 5 noted that: “…I don’t think anyone can stay in a job for 15 years if they don’t feel any self-satisfaction…”

Impact on Clients

The respondents also identified various impacts of charity work on the personal lives of their clients. For instance, the respondents reported that their involvement in charity work helps to empower the clients and enable them improve their lives in a manner that they could have not achieved on their own. For example, respondent 3 said that: “…So, I think with advocacy particularly, you're helping them to empower themselves to stand on their own feet..…” Respondent 6 also said that: The biggest joy we get is when parents come to us to prevent social services taking their children away from them. If we can prevent that, parents get so much joy…” It also emerged from the interviews that charity work enables the clients to be independent and develop a sense of responsibility to do things on their own. For instance, respondent 3 noted that “…we are helping them to do it and show them that they can do it without us…”

Question 4: What motivated them to stay in charity work?

While earlier responses indicated that charity workers sometimes lose the motivation to provide charity services, some respondents mentioned various factors that motivated them to continue working with charity organizations.

Passion and personal satisfaction

It became apparent that charity workers were motivated to continue with charity work by for the same reasons they decided to engage in charity. For instance, respondent 1 said that: “…Yes, I thought about leaving voluntary sector, but I don't think I can bring myself to work in the private sector or public sector. But in some respects, on my understanding to some degree, I think I would not get on in the private sector. In my whole working life even when I was in college, I always spoke up and raised my voice to unfairness and I know I wouldn't be very popular…” Moreover, respondent 3 noted that: I think it is because I've had some positive feedback from people have supported as an advocate, they've been sweet. And then it makes you feel that you know, you have made a difference to that person. And so maybe I'll hang around a bit more, make a difference to someone else. So that's what makes you keep going. It's not for the money. This is because of the satisfaction you get.

Chapter 5

5.0 Discussion and Conclusions

It appears from the interviews that motivations for working in charities are different from what other pieces of literature indicate. Generally, it seems that self-oriented motivations drive charity workers. Hence they respond to questions about motivations in terms of personal development, self-achievement, self-reliance, and generally self-driven motives. Besides, a majority of their work seems to be obligatory, because of the work in paid charities. For instance, when the interviewees were asked about why they joined charity work and what motivated them to stay, a majority of them mentioned they mentioned items like passion, personal belief, and unemployment. Contrariwise, only a few mentioned love and compassion for others, as well as the need to help others as their motivation. In general terms, though, this is contrary to what other pieces of literature have claimed. For instance, Omoto & Snyder (1995) found that individuals tend to engage in charity for purposes of civic engagement than self-focused aspirations. From our analysis, it is also apparent that the perceived impact of charity work on the workers and clients may be a motivation to join and stay in charity organizations. On this note, several impacts of charity work on the charity workers and the clients they serve. For instance, a majority of the respondents indicated that working in charities creates an opportunity to improve their career experiences through on-the-job training and other capacity-building programs implemented in those organizations.

Furthermore, the respondents mentioned that working in charity has helped improve their social lives in terms of knowing and working with other people besides creating an opportunity for personal satisfaction. These findings corroborate with the results of other studies evaluating the benefits and challenges of charity work. For instance, Scileppi et al (2000) & Berger (2006) found that despite various motives of joining charity work such as professional or social prestige, satisfaction and doing the organization a mere favor, charity workers are likely to make new friends, develop passion and find a meaning to charity work especially when their leaders appreciate them. When asked about the impacts of charity work on them and their clients, the respondents mentioned that engaging in charity helps to empower their clients, develop their independence, and create a sense of responsibility in them. These findings corroborate with the results of other earlier studies (e.g., Mesch 1998) who concluded that engaging in charity work creates an opportunity for developing a sense of responsibility for others and to actively participate in making decisions (e.g., funding and policy) that empower others. Furthermore, Chacon et al. (2007), on the subject of charity workers’ duration of service, concluded that in the curse of their duties, charity workers engage in training, develop a sense of being useful, and improved their quality of life. Similar remarks were made by Strigas (2006) who observed that in the course of their duties, charity workers create a significant impact on the lives of their clients and community at large by engaging in different activities such as resource mobilization and participating in progressive programs within the charity organizations. It is also apparent that charity workers are motivated to stay in charity when they realize that their efforts are paying off. Hence, positive feedback from either the clients or leaders enhances their commitment and motivation to continue with charity work.

These findings are relevant to the theory of role identity, which claims that the salience people attach to their identities, motivates them to engage more in activities that enhance their self. Therefore, in this study, we draw from the theory of role identity to make an argument that the self-satisfaction and other benefits attached to charity work enhances the salience connected to their identities, and this motivates them to stay on the charity organization to continue delivering service. The theory’s emphasis on the self is especially useful in the analysis of how self-satisfaction, passion, and personal improvement act as real motivators to people’s engagement in charity work. The interview report revealed key barriers to involvement in charity work, which includes inadequate resources, burnout, negative client perception, and poor coordination or teamwork. These findings point out to real challenges faced by both junior and senior charity workers that have also been identified by existing research evidence that have also identified lack of clear job descriptions, and inadequate skills as additional barriers. For instance, Morton (2014) identified that sometimes charity workers fail to have a clear description of their roles, face financial constraints to implement charity programs, and succumb to job burnout due to inadequate personnel to complete all the available tasks. The Jennissen & Lundy (2011) found further that even if there were adequate personnel, they would still face challenges related to poor coordination of roles and lack of teamwork to efficiently complete the tasks. While the emerging issues such as burnout and poor team coordination confirm that charity organizations are increasingly becoming professionalized, charity workers may not be aware of the implications of these changes to their careers, especially those who are contemplating to join charity work. This implies the need for increased support and training for charity workers on how to identify good charity work opportunities and develop a proper career in charity work.

A few respondents mentioned that they face negative perceptions from clients, especially when the clients’ expectations are not met. Existing research by Decosimo (2014) identified that the negative attitude held by society towards charity work emanates from a lack of understanding about charity work from a cultural perspective. This calls for extra resources to develop enlightenment programs aimed at delivering an expansive, diverse, and culturally acceptable conceptualization of charity work. Furthermore, a failure to have a clear understanding of charity work can be associated with stigmatization targeted at charity workers. It is therefore vital to make the society understand that charity work is a mainstream career whereby people earn a living by improving the lives of others. Furthermore, the negative client perceptions imply the need for a re-evaluation of the existing policy assumptions upon which charity work is based and how charity organizations contribute to the development of these policies. This study is concerned with the potentially emerging distinction between those who engage in charity work and those who do not. Besides, we argue that it is unhelpful to equate charity workers with good citizens and non-charity workers with poor citizens. Charity workers can demonstrate their citizenship and engage in activities that promote citizenship, but people may also make equally good contributions to society in many different ways. It is until the society is aware of these issues that charity workers will begin to experience reduced negative perception and stigmatization. A significant barrier to charity work is inadequate financial resources. The results of this study suggest that charity organizations. The respondents complained that they lack adequate financial resources to effectively implement programs and to provide optimal support to their clients. This raises an issue with the role of government in supporting charitable organizations through various aspects, including poor planning, consistent support, and consultation. While it is essential to acknowledge the role of government in supporting charity organization, the existence of inadequate support in some of the respondents’ organizations indicates that there is more work to be done by the government to address those deficits. Of particular interest should be the interlink between coordination and charity programs and policies and programs in other government sectors such as the legislative barriers.

5.1 Conclusion

This study has established the essential roles played by charity workers in enhancing the lives of their clients. Furthermore, the research has found various motivations and experiences of charity workers, and apparently, their experiences have exceeded what they expected. By deciding to engage in charity work, they change their lives and the lives of their clients within the society. All these enhance their commitments to their respective organizations and more importantly improves their client’s quality of life.

5.2 Recommendations

Based on the findings of the current study, charity organizations should treat their employees with transparency and dignity to motivate them and have them remain in the organizations. Charity workers value transparency, effective communication and proper teamwork coordination, and the extent to which they are properly treated should not only be limited to the workplace but should extend to the fieldwork. When charity workers are given peace of mind and assured of smoother operations, they are likely to be more motivated to work hard and provide suggestions about what should be improved. Hence, effective and regular communication is needed to enhance the effective operations of charity organizations.

Charity workers are also likely to appreciate it when their feedbacks and suggestions about personal needs are put into consideration. Their ideas can help eliminate additional training needs, thereby saving more money for more superior career development programs or support newer recruitments. The importance of training and skill development also raises the need for charity organizations to outsource better skills and enhance the worker’s professional accreditation.

References

Apan, S. D., Quartaroli, M. T., & Riemer, F. J. (2012). Qualitative research: an introduction to

Bloor, M & Wood, F. (2006) Keywords in Qualitative Methods: A Vocabulary of

Berger. I. E. (2006). The influence of religion on philanthropy in Canada. Voluntas, 17, 115–132.

Chacón, F., Vecina, M. L., & Dávila, M. C. (2007). The three-stage model of volunteers’ duration of service. Social Behaviour and Personality, 35, 627-642.

Given, L. M. (2008). The Sage encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. Los Angeles, Calif , Sage Publications.

Hurley, N. Wilson, L. Christie, I. (2008) Scottish Household Survey Analytical Topic Report:

Howlett, S. (2008) Lending a hand to lending a hand: The role and development of volunteer centers as infrastructure to develop volunteering in England. Volunteering Infrastructure and Civil Society Conference. Aalsmeer, Netherlands.

Institute of Volunteering Research (2007) Young people help out - Volunteering and giving among young people. Helping Out Research Bulletin, IVR, London.

Institute for Volunteering Research and Volunteering England (2007) Volunteering Works. Volunteering and social policy. London.

Low, N., Butt, S., Ellis Paine, A. and Davis Smith, J. (2007) Helping out: a national survey of volunteering and charitable giving London: The Cabinet Office.

Milligan, C. and Fyfe, N. (2005) 'Making Space for Volunteers: exploring the links between voluntary organisations, volunteering and citizenship', Journal of Urban Studies, 42:3.

National Council for Voluntary Organisations (2009) The State and the Voluntary Sector – recent trends in government funding and public sector delivery. NCVO, London.

Omoto, A. M., & Snyder, M. (1995). Sustained helping without obligation: Motivation, longevity of service, and perceived attitude change among aids volunteers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 671–686.

Stanley, K. (2004) More than a numbers game: a UK perspective on youth volunteering and active citizenship. Prepared for Council of Europe & European Commission Seminar on How does the voluntary engagement of young people enhance their active citizenship and solidarity?‟ Budapest, 5th – 7th July 2004.

Voluntary Service Bureau (2007) Why not ask me - research into volunteering and community relations amongst young people in Belfast.

Zimmeck M (2009) The Compact Code of Good Practice on Volunteering: Capacity for change: A review. London. Institute for Volunteering Research.

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts