Use of Legislation For Achieving Pay Parity

Use of legislation for achieving pay parity and for women at workplace - The European

Pay parity in the context of gender equality at workplace is one of the areas that has received significant attention from literature. Today, pay parity is considered to be a concept of human rights of women at workplace as a part of the right to equal pay for equal work or work of equal value; as such, it is a part of the concepts of gender equality and employment equity (Farrell, 2005). Lack of pay parity can amount to gender discrimination at workplace and can have negative implications for the female employees who are not paid the same amount as the male employees; such negative impacts are seen in the decrease of motivation, satisfaction, commitment, and the stress levels amongst female employees (Channar, Abbassi, & Ujan, 2011). As absence of pay parity can be related to gender discrimination, it can lead to low levels of satisfaction with the employment, and decreased commitment to work further, which may also lead to higher levels of attrition for the female employees (Channar, Abbassi, & Ujan, 2011). As such, the employer’s failure to pay equally for work of equal value to both male and female employees can have negative impacts for the rights of women to work and employment and for these reasons it has implications for human rights of the employees.

Significant provisions in the international law, including the treaties formed under the International Labour Organisation have already responded to the issue of pay parity at workplace as a part of gender justice and gender equality. These will be discussed later in this literature review. This chapter seeks to provide a discussion on the important terms and concepts that are relevant to this dissertation, such as, pay parity, gender equality, gender justice, and also a discussion on the use of legislation to achieve these concepts in the workplace. A discussion on literature around the European legislation related to pay parity in the workplace is also undertaken in this literature review. Lack of pay parity in the workplaces has been considered to be a manifestation of systemic discrimination against women in the workplace (Agocs, 2002). Systemic discrimination is defined as structural and cultural patterns of organisational behaviour and decision-making processes that are central to the creation of an environment in which there is “relative disadvantage for members of some groups and privilege for members of other groups” (Agocs, 2002, p. 258). The compensation which is given to the members of the workplace can reveal the existence of such systemic discrimination when some members are subjected to a relative disadvantage vis a vis the others by being paid less than the others (Agocs, 2002). While there are other reflectors of systemic discrimination at workplace, compensation cultures is one of the important indicators of systemic discrimination. The term systemic is used in literature apparently to indicate the permeation of discriminatory practices into the general organisational culture. The word systemic also refers to the embedding of the cultures of discrimination within the system, which may make it difficult for those who are marginalised (in this case women employees) to receive redressal against discrimination unless there are positive measures adopted by the organisation to reform organisational culture and adopt gender equity related practices, including pay parity. Literature indicates that the issue of pay parity is a serious and ongoing issue in the workplaces around the world, due to which women continue to be paid lesser than their male counterparts for work of equal value (Schwanke, 2013).

The universality of the phenomenon of gender inequity at workplace as reflected in the lack of pay parity, indicates that there is indeed an issue of systemic discrimination against women (Mandel & Semyonov, 2014). Literature also indicates that there are a number of institutional and structural factors that may be responsible for the lack of pay parity in the workplaces; four main factors include: “labour market–relevant attributes, labour supply, occupational segregation, and employers’ discrimination” (Mandel & Semyonov, 2014, p. 1598). These factors are relevant to understanding why women continue to be paid lesser than their male counterparts for work of equal value and how lack of pay parity is perpetuated in the work environment. This is relevant to understanding how legislation may be important to correcting the gender inequity in workplace in the specific context of pay parity. The study conducted by Mandel and Semyonov (2014) explored the issue of gender pay gap in the United States from 1970 to 2010, thus covering 4 decades in the study. Collecting the data from the IPUMS-USA, the study found that there was lack of pay parity not only in the private but also in the public sector (Mandel & Semyonov, 2014). The identification of the four principal sources for gender pay gap as “labour market–relevant attributes (i.e., human capital), labour supply, occupational segregation, and employers’ discrimination” are the important findings of this study (Mandel & Semyonov, 2014, p. 1598). Occupational segregation, which is one of the important factors identified by the study as responsible for lack of pay parity, has been defined in another study as the phenomenon of men and women working in different occupations (Blau, Brummund, & Liu, 2013). This relates to gender segregation at the workplace. The issue of gender segregation at work is one of the important factors that is identified in literature as a reason for lower pay for women workers for work of equal value (Simpson, 2004). The concept of male dominated and female dominated occupations has been a long standing issue in employment sector, with some occupations like engineering, being heavily dominated by men, although that is changing. These occupations are better paid. On the other hand, occupations like health care and child care, which have been traditionally considered to be female dominated, have been low-wage industries irrespective of the skill level required in that industry (Simpson, 2004). Ironically, experience indicates that when men move into female dominated professions, salaries have increased generally for that profession and when women move into male dominated occupations and there is subsequently significantly large number of women employees in that profession, there is a drop in the average pay for these jobs (Lambert, McInturff, & Lockhart, 2016).

One study provides an in-depth review of literature between 1970 to 2010 on occupational segregation or gender segregation (Blau, Brummund, & Liu, 2013). The study developed a gender specific crosswalk based on dual-coded population survey data by which the researchers identified and analysed trends on the basis of occupational codes and data sources (Blau, Brummund, & Liu, 2013). They found that occupational segregation was high in the early part of the study but began to slow down and decline in the 2000s (Blau, Brummund, & Liu, 2013). However, the study noted that although there was a decline in occupational segregation, it was a modest decline and there is still occupational segregation in play and which affects the chances of women to receive equal pay for work of equal value (Blau, Brummund, & Liu, 2013). The above indicates a structural issue with relation to pay parity in the employment sector between men and women. It may be argued that gender pay gap is perpetuated institutional and structural manner. The literature discussed above are empirical studies into the issue of pay parity and this literature indicates that the lack of pay parity is a part of cultures of discrimination (Simpson, 2004; Lambert, McInturff, & Lockhart, 2016). Due to the structural nature of the issue of lack of pay parity in the workplace, literature has tended to see this issue as one that can be properly addressed through legislation. The experience of countries that have adopted such legislation in bringing pay parity is one of the reasons why some scholars argue that the most effective way to address structural and institutional discrimination against women manifested in the lack of pay parity can be brought about by introducing legislation (Krahn & Hughes, 2007). Legislation makes it mandatory for the employer to provide equal pay for work of equal value and this is one of the reasons why it is argued that "the agenda of equality in employment can be achieved more effectively and sooner through bold public policy initiatives" (Krahn & Hughes, 2007, p. 206). Krahn and Hughes (2007) write on the basis of the Canadian experience where legislation has been introduced to ensure pay parity by making it lawfully binding on the employers to provide equal pay for work of equal value. They argue that the provision of equal pay provisions in the legislation in Canada has led to more effective application of the principle at the workplace because employers have legal obligation to ensure equal pay for work of equal value in Canada (Krahn & Hughes, 2007).

Similarly, the experience of the European Union may also be relevant to understanding how legislation and enforcement of pay parity norms can lead to the ensuring of the structural and institutional changes required to bring about pay parity. The most important step taken recently in this direction is the European Union Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), which enshrines the principle of equal pay for work of equal value in its Article 157 (1). This is the most important provision on the right to equal pay for work of equal value in the European Union. As will be discussed in later, there is some academic disagreement on whether Article 157 (1) defines ‘pay’ in a satisfactory manner from the perspective of its interpretation because there is an argument that the definition is as yet not clearly developed and therefore fails to protect the right of women for equal pay for equal work under varied circumstances. It may be mentioned that the European Court of Justice has been responsible for the interpretation of the word ‘pay’ and the jurisprudence on definition has evolved over time, with the interpretation being considerably wider than could have been understood from the wording of Article 157 (1) (IDS, 2008, p. 71). The actual text of Article 157 (1) reads as follows: “1. Each Member State shall ensure that the principle of equal pay for male and female workers for equal work or work of equal value is applied. 2. For the purpose of this article, ’pay’ means the ordinary basic or minimum wage or salary and any other consideration, whether in cash or in kind, which the worker receives directly or indirectly, in respect of his employment, from his employer.” As can be understood from the wording of Article 157 (1), there is a bar on the employer from discriminating between male and female employees in the context of pay. The term ‘pay’ is also defined in the article as inclusive of the ordinary or minimum wage salary; however, the use of the words “any other consideration whether in cash or kind” allow the European Court of Justice to interpret the word ‘pay’ in a wider context by including consideration that could be made in cash or kind. Article 157 (1) also notes that equal pay has to be paid for “equal work or work of equal value”, this also opens the provision to interpretation by the European Court of Justice as the phrase work of equal value can be broadly interpreted. From this brief discussion on Article 157 (1), it can be understood that there are some important terms and phrases in the provision that need to be interpreted; these include ‘workers’, ‘pay’, and ‘work of equal value’ (Burri & Prechal, 2014). The term worker

has been defined by the court as “a person who, for a certain period of time, performs services for and under the direction of another person in return for which he or she receives remuneration” (Deborah Lawrie-Blum v Land Baden-Württemberg, 1986, p. para 17). The word ‘pay’ was interpreted narrowly in Defrenne v Sabena (No. 2), with the court not including pension benefits in the term ‘pay’ although the court has rectified this in the subsequent cases (Foster, 2012). In Defrenne, the issue related to the provision of social security schemes made by the employer for the benefit of the employees (Gabrielle Defrenne v Société anonyme belge de navigation aérienne Sabena, 1976). This case is important because although the court interpreted the word ‘pay’ narrowly, the interpretation of the Court of Justice led to development of the definition of the word in subsequent cases; the court held that although the concept of social security benefits is a part of the concept of pay, those social security schemes or benefits, such as retirement pensions that are directly governed by legislation will not be a part of the term for the purposes of the European law on equal pay for equal work as these benefits are given to the employees without any element of agreement and as part of the statutory provisions. Defrenne led to confusion on the aspect of pensions as part of pay because the court distinguished between the benefits that are provided by the employer as part of agreement between the employer and the employee, in which case the benefits are to be equally given and those benefits that are provided as part of statutory provisions. Such benefits, including pensions, were kept outside the purview of the definition of pay for the purposes of the European law. However, a link had been drawn between pensions and equal pay in Defrenne, which was further explored in subsequent cases, particularly the Barber case decided by the European Court of Justice (Douglas Harvey Barber v Guardian Royal Exchange Assurance Group [1990] ECR I-1889, 1990). The term ‘pay’ is now applied to the pensions given to the employees as well so that the employer may not discriminate against employees by giving some more than the others (Douglas Harvey Barber v Guardian Royal Exchange Assurance Group [1990] ECR I-1889, 1990). Prior to Barber, there was some uncertainty on the applicability of the principle of equal pay to occupational pensions, however, now it is clear that pensions also fall within the ambit of ‘pay’. The issue of pensions became important with respect to the concept of equal pay because of different retiring ages for men and women in some occupations; this may lead to women being at a disadvantage for pension schemes (IDS, 2008, p. 81). In Barber, the court clarified that pensions would come within the meaning of pay where there is an agreement between the employer and the employees on the giving of pensions or when employer takes a unilateral decision for pensions provisions to the employees (Douglas Harvey Barber v Guardian Royal Exchange Assurance Group [1990] ECR I-1889, 1990). The overarching rule is that there should be an employment relationship from where pension schemes are derived and that such relationships should not be discriminatory with respect to certain employees on the basis of their gender (Chalmers, et al., 2014). The facts of the Barber case exemplify direct discrimination, which as per the judgment contrary to the principle of equal pay in European law contained in Article 157 (1) and the Recast Directive. Another example of direct discrimination in the case law is in the Griesmar case (Joseph Griesmar v Ministre de l'Economie, des Finances et de l'Industrie et Ministre de la Fonction publique, de la Réforme de l'Etat et de la Décentralisation Case C-366/99 (2001), 2001). In this case, the facts showed that service credit for the calculation of the retirement pension was given only to female civil servants with children whereas women who did not have children did not receive similar service credit; this was held to be an instance of direct discrimination against a group of employees and a violation of the equal pay principles in the European law (Joseph Griesmar v Ministre de l'Economie, des Finances et de l'Industrie et Ministre de la Fonction publique, de la Réforme de l'Etat et de la Décentralisation Case C-366/99 (2001), 2001).

Reports exploring the application of European laws in this area have shown that while there still are gender pay gaps in many European countries, the gender pay gap has been closing after the enforcement of the European law in this area (European Commission Employment, 2009). Some of the steps taken by the European Union in bringing about the pay parity legislation are discussed in the following sections. One of the important steps taken by the European Union is the Council Directive 75/117/EEC of 10 February 1975. This Directive explains the principle of equal pay in the following manner: “for the same work or for work to which equal value is attributed, the elimination of all discrimination on grounds of sex with regard to all aspects and conditions of remuneration” (Article 1). Interestingly, the Directive has also mentioned that the principle of equal pay for equal work is an integral part of the establishment and functioning of the common market and the Member States are asked to ensure that they take all necessary measures to safeguard that “provisions appearing in collective agreements, wage scales, wage agreements or individual contracts of employment which are contrary to the principle of equal pay shall be, or may be declared, null and void or may be amended” (Article 4). This Directive was repealed in 2006 by Directive 2006/54/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 July 2006 on the Implementation of the Principle of Equal Opportunities and Equal Treatment of Men and Women in Matters of Employment And Occupation. This recent Directive 2006/54/EC is also called as the ‘Recast Directive’. The Recast Directive replaced the 1975 Directive. One of the reasons why the Recast Directive was enacted was because of the emerging jurisprudence and understanding on equal pay for work of equal value and the need to align the legislation and norms of the European Union with the emerging line of jurisprudence developed by the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR). It would be pertinent to discuss this jurisprudence to get an idea of how the Recast Directive has been introduced to align European practice in companies and workplaces with the emerging jurisprudence. The term ‘equal pay’ is defined in the Recast Directive as follows: “For the same work or for work to which equal value is attributed, direct and indirect discrimination on grounds of sex with regard to all aspects and conditions of remuneration shall be eliminated. In particular, where a job classification system is used for determining pay, it shall be based on the same criteria for both men and women and so drawn up as to exclude any discrimination on grounds of sex” (Recast Directive, Article 4). The above definition may be seen in the context of the direct and indirect forms of discrimination that may impact the equal pay rights of women. It may be recalled that Article 157 (1) bars both direct and indirect gender based discrimination in the work place. Direct discrimination is defined in the context of being treated as less favourably on the ground of gender, where it can be clearly seen that but not for gender, the person discriminated against would have been treated more favourably (IDS, 2008, p. 31). Indirect discrimination is involved where the actual acts or decisions may be gender neutral but, may have the effect of putting a particular gender at a disadvantage in comparison to the other (IDS, 2008, p. 31). The Recast Directive bars both the direct and indirect forms of discrimination against women with respect to payment for work, which is to be done equally for all. Therefore, the scope of the Directive is wide and includes any action that can have the effect of direct or indirect discrimination. The Recast Directive emphasises on the recognition of the principle of equal pay for equal work by considering the evolving jurisprudence of the principle; this is important because the Recast Directive indicates that the jurisprudence on the principle of equal pay is still evolving. This means that the European Union recognises that the principle is evolutionary in

nature. The Recast Directive also recognises that gender equality is a fundamental principle of Community law under Article 2 and Article 3(2) of the Treaty. Recast Directive provides that the principle of equal pay for equal work or work of equal value as laid down by “Article 141 of the Treaty and consistently upheld in the case-law of the Court of Justice constitutes an important aspect of the principle of equal treatment between men and women and an essential and indispensable part of the acquis communautaire, including the case-law of the Court concerning sex discrimination” (Recast Directive, 2006). This is important because it indicates that the case law developed by the Court of Justice is important for conceptualising and contextualising the right of equal pay for work of equal value. A range of factors are to be used for determining the comparability of the work between men and women for deciding on applicability of the principle of equal pay; these include, the nature of work and training and working conditions of the different workers, which can help to assess whether the men and women are involved in providing work of equal value or not. The Recast Directive clarifies the issue of pension schemes for the purpose of defining pay and has noted that such pension schemes for public servants falls within the scope of the equal pay principle. This is according to the jurisprudence developed by the Court of Justice, wherein it has held all benefits that are part of the employment scheme are to be equally provided to both the male and the female employees and that the failure to do so would amount to discrimination between male and female employees (C-7/93: Bestuur van het Algemeen Burgerlijk Pensioenfonds v G. A. Beune (1994 ECR I‐4471). , 1994). In another case, it was held that sick-leave scheme that treats pregnant female workers on par with other workers suffering from illness unrelated to pregnancy would be contrary to the principle of equal pay for equal work and would come within the scope of the Directive (NorthWestern Health Board v McKenna Case C - 191/03, 2005). The issue of whether maternity pay also comes within the domain of the word ‘pay’ has also come before the European Court of Justice, and the court has included maternity pay in the definition of pay in Gillispie v Northern Health and Social Services Board, wherein the court held that because maternity pay is a benefit, which is given to female employees by the employer under a relationship of employment, it is part of the definition of pay in Article 157 (1) and comes within the purview of equal pay (Gillispie and Others v Northern Health and Social Services Board and others, 1996). Therefore, the term pay was expanded further to include maternity benefits. The existing jurisprudence of the Court of Justice would include all jurisprudence on the issue of equal pay for equal work, including under the 1975 Directive. Indeed, the directives created by the European Union have been recognised as important to the law on equal pay for equal work in Europe as also noted by the Court of Justice: “the principle of equal pay laid down in Article 119 of the Treaty and set out in detail in Directive 75/117 on the approximation of the laws of the Member States relating to the application of the principle of equal pay for men and women neither requires that women should continue to receive full pay during maternity leave, nor lays down specific criteria for determining the amount of benefit payable to them during that period, provided that the amount is not set so low as to jeopardize the purpose of maternity leave, which is the protection of women before and after giving birth. In order to assess the adequacy of that amount, the national court must take account, not only of the length of maternity leave, but also of the other forms of social protection afforded by national law in the case of justified absence from work” (Joan Gillespie and others v Northern Health and Social Services Boards, Department of Health and Social Services, Eastern Health and Social Services Board and Southern Health and Social Services Board C-342/93., 1996).

Therefore, one may consider the law on equal pay for equal work as part of a developing jurisprudence of the European Court of Justice. The Recast Directive is the important law on equal pay at this time and one which has consolidated other directives of the European Union along with the case law of the European Court of Justice (European Commission Employment, 2009). More importantly, by emphasising on the developing nature of the jurisprudence on equal pay, the Recast Directive keeps the door open for more additions to the term ‘pay’ and ‘workers’ because these are open to interpretation by the European Court of Justice. There are some important points that can be noted about the European regime on equal pay. First point of importance in the developing jurisprudence of the European Union, is that the traditional meaning of pay has been evolved and widened by the ECtHR. Pay also includes like pension schemes, which the ECtHR has held needs to be equally applied to male and female employees (C-7/93: Bestuur van het Algemeen Burgerlijk Pensioenfonds v G. A. Beune (1994 ECR I‐4471). , 1994). Similarly, overtime supplements have been included in the term pay so that male and female employees are treated similarly in the dispersal of these supplements (Ursula Voß v Land Berlin , 2007). Pay also includes bonuses given to employees for their performance so that female and male employees are given same bonuses for the same level of performance (Susanne Lewen v Lothar Denda, 1999). The ECtHR has also included travel facilities in the term pay (Eileen Garland v British Rail Engineering Limited , 1982). The difference between male and female employees in terms of pay parity is also narrowed by holding that compensation paid for attendance of trainings and seminars is also pay for the meaning of the European Union legislation and Directives on this issue (Arbeiterwohlfahrt der Stadt Berlin e.V. v Monika Bötel, 1992). However, one gap in the regime on pay parity is that those who are not full time employees, may not come within the domain of Article 157 as was demonstrated by the Allonby case (Allonby v Accrington & Rossendale College (2004) C-256/01, 2004). The petitioner in this case was a temporary teacher in a college, and was paid lesser than her male colleagues although the work done by her was the same as the work done by her male colleagues. The Court however held that her case did not come within the purview of Article 157 (Allonby v Accrington & Rossendale College (2004) C-256/01, 2004). The difficulty was related to the interpretation of the word ‘worker’ under Article 157 (1), related to which the court held that it could not extend the term worker to those who provided services under temporary work arrangements or under contracting out services (Allonby v Accrington & Rossendale College (2004) C-256/01, 2004). The question that could be raised in such situations is whether more men as compared to women were being given the provisions of permanent work. If that is the case then the problem could arise where women are kept out of permanent work and paid less without attracting the protection afforded by Article 157 (1), so that women can be denied equal pay without attracting the provisions of the European law. On the other hand, it is necessary to draw comparisons between two individuals in order to assess whether the principle of equal pay for equal work is being applied to work of equal value. When work of equal value is assessed, consideration must be had to whether there is equality of the work value. This may mean that a difference is drawn between temporary and permanent employees as was the case in Allonby (Allonby v Accrington & Rossendale College (2004) C-256/01, 2004). Such comparisons may also mean that court draws the contrast between male and female employees to see if the work is of equal value. The Recast Directive itself provides that court needs to assess the value of work being done by two comparable individuals to determine the applicability of the equal pay provisions to the petitioner. Para 9 of th Recast Directive provides this, as noted below:

“In accordance with settled case-law of the Court of Justice, in order to assess whether workers are performing the same work or work of equal value, it should be determined whether, having regard to a range of factors including the nature of the work and training and working conditions, those workers may be considered to be in a comparable situation” (Recast Directive, para 9). The application of this provision in one case led the court to conclude that a classification of employees in the same job category would not in itself be adequate to draw a conclusion that the male and female employees are involved in providing work of equal value to the employer (Susanna Brunnhofer v Bank der österreichischen Postsparkasse AG, 2001). What can be concluded from this discussion on cases decided by the European Court of Justice on the interpretation of the word pay is that Article 157 (1) has been interpreted to include benefits, including pension and maternity benefits so that the term goes beyond the inclusion of basic salary or wages, and goes on to include any other benefits under the employment agreement or as a unilateral decision of the employer. However, for assessment on whether someone needs to be included within the scope of the protection offered by Article 157 (1), the court can see the application of the word worker to include the individual or exclude them from the protection of the provision. Thus, temporary female employees may not be able to get the protection of equal pay to put them in the same position as male employees that are permanent. Moreover, the determination of whether equal pay is denied would also depend on the comparison with the other employees. In drawing such comparison, it would not be enough to show that the employees are all classified under the same description of jobs; what will be relevant is whether the employees are providing work of equal value to the employer or not. This may mean that although the employees are all involved in the same classification of jobs, they are not doing the same work as each other and therefore cannot be compared for the purpose of equal pay. The second point of importance in the developing jurisprudence is that it creates principles of law that are binding on the European countries that are members of the European Union. European countries have had to change and amend their national laws so as to ensure that the developing jurisprudence of the European courts is applied to these countries also. UK enacted the Equal Pay Act 1970 for this very purpose so that women employees are paid equally for the work of the same value (Macarthys Ltd v Smith (1980) ICR 672, 1980). Macarthays Ltd v Smith is also a relevant authority to understand how the women employees are protected in their compensation because in this case the European Court of Justice held that if a woman employee is paid lesser than her male predecessor, it is a violation of the pay parity law of the European Union (Chalmers, Davies, & Monti, 2014). Therefore, this also means that the developing jurisprudence binds the national courts as well and they have to keep abreast of the developments in the European law and apply the principles developed to the cases that come before them. If these principles are not applied then the petitioners can have recourse to the European courts. The principle of direct effect of European law is applicable here and ensures that layers of protection are created for the petitioners under the national as well as the European law. At the national level, the protection is created through the principle of supremacy of the EU law, which was developed by the European Court of Justice and which requires national courts to give effect to the law developed by the European Union (Costa v Enel (1964) 6/64, 1964). Thus, the common core of rights protected by Article 157 (1), and supplemented by the judgments of the European Court of Justice, are essential to the interpretation of the principle of equal pay for equal work even by the national courts. If the national courts fail to implement the European law on equal pay then the petitioner can approach the European

Court of Justice or the European Court of Human Rights (Costa v Enel (1964) 6/64, 1964). This is demonstrated by the decision of the court in Macarthys Ltd v Smith, where the European Court of Justice held that irrespective of the provisions in the British Equal Pay Act 1970, the matter came within the domain of Article 157 (1) (Macarthys Ltd v Smith (1980) ICR 672, 1980). This is one of the cases where the court directed a national court to dis-apply a national law and apply Article 157 (1) in its place in order to ensure that the conflicting national law would not come in the way of the court ensuring the protection afforded by the equal pay law developed in Europe (Chalmers, et al., 2014, p. 579). The European example is unique because of the community law, which may not at this time be applicable to other jurisdictions; however, the example also shows that legislation can be effective in addressing the problem of lack of pay parity at work place. This does not mean that literature suggests that legislation in Europe is completely effective in doing away with gender inequity at the work place, which is manifested by the lack of pay parity. Indeed, the interpretation of the term pay is central to ensuring that women are paid equally as their male counterparts because employers may use narrow interpretation of the term pay to ensure that while they pay equal salaries to men and women employees, but then they give more benefits to men. It has been observed that the motivating factors for the inclusion of TFEU, Article 157(1) is to ensure that there is no unfair manner of giving male employees more benefits than women and doing indirectly (compensating men more) what cannot be done directly (European Commission Employment, 2009). It may be mentioned here that the structural and institutional factors are so deeply entrenched to favour male over female employees, that even in the European Union, the pay gay is narrowing at a slow pace. This is despite the legislation passed to bring about pay parity and decades of development of a jurisprudence which seeks to put women at equal footing as their male counterparts at the workplace. A recent report European Commission Employment pertinently observes: “Despite the fact that the principle of equal pay is reflected both in the resolution of the European Parliament of 18 November 2008 with recommendations to the Commission on the application of the principle of equal pay for men and women (2008/2012(INI)) and in national legislation strengthened by numerous decisions of the European Court of Justice, the current average pay gap across the European Union (EU) remains very high: across Europe women earn on average 17.4% less than men and in some countries the gender pay gap is widening” (European Commission Employment, 2009, p. 5). The above is reflective of the structural and institutional factors that are responsible for the embedding of male domination at workplace which is reflected in the way men and women are compensated for work of equal value. Recognising that these aspects of work related inequity are continuing despite the efforts of the European Union through the TFEU and the directives issued by it, the European Commission has also adopted the 'EU Action Plan 2017-2019: Tackling the gender pay gap' in November 2017. There are 24 action points in this Action Plan, and 8 main strands of action: (i) Improving the application of the equal pay principle; (ii) Combatting segregation in occupations and sectors; (iii) Breaking the glass ceiling: addressing vertical segregation; (iv) Tackling the care penalty; (v) Better valorising women's skills, efforts and responsibilities; (vi) Uncovering inequalities and stereotypes; (vii) Alerting and informing about the gender pay gap; and (ix) Enhancing partnerships to tackle the gender pay gap ( European Commission, 2017). The Action Plan has been created considering the continuing pay gap problem in many European countries despite decades of efforts to bring pay parity into the work space. The Recast Directive remains the primary

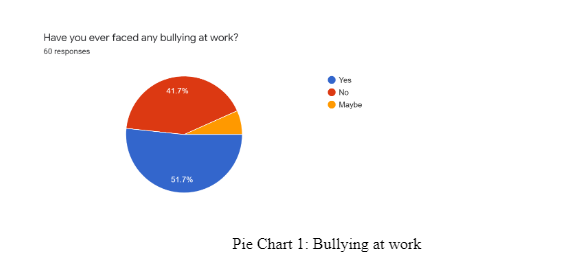

instrument by which the European Union seeks to make legal obligations work effectively to make the employers pay their employees equally for equal work. The literature discussed in this section suggests that there is addressing of the problem of absence of pay parity at work and that the courts have also been active in interpreting the protection of equal pay for work of equal value. However, the literature does not indicate that the enacting of the law has led to the complete elimination of unequal pay in the work places in Europe. It is indicated that legislation creates conditions within which those who are aggrieved by the lack of pay parity may approach the courts in their nation or in Europe for getting remedies against their employers. However, the literature does not indicate to what extent this has led to the reduction of discrimination against women in terms of their getting equal pay for equal work or work of equal value. Therefore, there is a gap in literature on European law on the right to equal pay for equal work, in that, the literature discusses the provisions on the right and the authorities related to the same, but it does not show how far these laws and authorities have managed to replace the established structural and institutional factors that are responsible for the embedding of male domination at workplace which is reflected in the way men and women are compensated for work of equal value. This research has used a questionnaire instrument to probe how female employees at workplace experience the issues related to equal pay for equal work. The purpose of this method was to probe the actual experiences of the female employees and analyse the European legislation in the light of these experiences. The findings of the study are reported in the next section. Findings This chapter reports the findings of the questionnaire put forth to the participants in this research. The questions probed the experience of the participants with respect to their workplace. The questions put forth to the participants were close ended, therefore, these questions only allowed the participants to answer the questions in the affirmative or negative. The first three of the twelve questions posed to the participants were in the nature of the personal questions on their age, gender, and nationality. The majority of the participants were in the age group of 20 to 30 years (38.3%), followed by participants in the age group of 30 to 40 years (31.7%). 18.3% of the participants were in the age group of 41 to 50 years old and 11.7% of the participants were in other age groups, that is, below 20 years or above 50 years old. The participants represented both male and female samples. The majority of the participants were female (47.4%), followed by 33.3% males and 19.3% who did not want to specify their gender. The participants were mixed in terms of nationality. American, French, Gambian, Indian, and Spanish nationalities were represented in the sample of participants. The majority of the participants were Americans (47/1%) followed by Gambians (17.6%), and Spanish (5.9%). Participants were asked if they had ever faced bullying at work. Majority of the participants have replied in the affirmative as represented in the Pie Chart 1 below. 51/7% of the participants reported that they had faced bullying at some or the other time in their workplace and 41.7% of the participants reported that they had never faced any bullying at their workplace. A small percentage of the participants did not give a clear answer replying that they may have faced bullying at workplace. This suggests that bullying at workplace may be a common practice with many participants experiencing such behaviour.

Participants were also asked if they had ever experienced verbal abuse or physical harassment at their place of work. Again, majority of the participants reported that they had experienced such behaviour with 55% of the participants replying to this question in the affirmative. 43.3% of the participants reported that they had not experienced such behaviour at their workplace as reflected in the Pie Chart 2 below.

Participants were also asked about the conditions of their workplace in terms of the number of hours they worked in the week. They were asked if they worked more than 60 hours in a week. Majority of the participants responded in the negative with 56.7% of the participants replying that they do not work these many hours in a week. However, a significant number of participants (41/7%) do report to working these high number of hours in a week. If these participants are working five days a week, then that would mean that 41.7% of the participants are working 12 hours a day. This is reflected in Pie Chart 3 below.

Regarding conditions of work, participants were also asked if they were exposed to health hazards of harm at their workplace. The responses show a clear divide in the experiences of the participants. 50 percent of the participants reported to exposure to hazard or harm at workplace and the same number has replied in the negative, as reflected in Pie Chart 4 given below. Considering that the majority of the participants in this sample were women, this means that a significant number of women could also be exposed to hazard or harm at workplace.

Pie Chart 4: Exposure to hazard or harm Questions related to conditions of work also included a question on the salary or any problems or concerns with relation to the same for the participants. As Pie Chart 5 represents below, 50% of the participants reported to having problems, issues or concerns with their salary and the same number did not report to having similar concerns. Considering the research question in this study being focused on the issue of pay parity between male and female employees, this was an important question and the response indicates that there are significant number of participants who have issues with regard to their salary.

With regard to conditions at workplace, another question that was posed to the participants was whether they have ever experienced bad behaviour at their workplace. As Pie Chart 6 below represents, 51.7% of the participants have reported to experiencing such bad behaviour at their workplace, while 41.7% reported that they have not faced or experienced such bad behaviour at their workplace. Significantly, about 7% of the participants report that they may have experienced such behaviour at their workplace. This suggests that for a significant number of the respondents, conditions at their workplace may involve exposure to such bad or abusive behaviour.

Participants were also asked if they received sufficient rest breaks in their workplace. A higher number of participants (55%) reported that they did get sufficient rest breaks at their workplace. However, a significant number of workers (43.3%) reported that they did not receive adequate rest breaks in their work day. A small number of participants reported that they may or may not be receiving sufficient rest breaks in their work day. These responses are reflected in Pie Chart 7 below.

Participants were also asked whether they would like to make any suggestions for the improvement of their work place experience. Only 11 participants responded to this question as represented in Pie Chart 9 below. However, the responses show a variety of suggestions that were made by the participants for the improvement of their work place experience.

These responses as reflected in Pie Chart 9 above, suggest that work place conditions can be improved if management is more transparent, information is shared freely, workers are treated without any partiality, and workers are treated equally particularly in the context of their pay parity. The last suggestion is important because it reflects on the principal question of this research study, which relates to pay parity at workplace. Considering that the majority of the participants in this research study were women, and the majority of the participants expressed concerns or problems with the salary issue, it is significant that this suggestion has been put forth. This finding suggests that an important component of work place satisfaction is that workers are treated equally, particularly in terms of the salary that is given to them. Discussion The responses to the questionnaire instrument suggest that there are a significant number of employees and workers who may be experiencing issues and problems with respect to the conditions that lead to workplace equality, particularly in terms of pay parity. Literature on this point has suggested that women all over the world, and in the European Union, do experience lack of pay parity and equality with their male counterparts at their work place. Indeed, lack of pay parity at workplace is described as a manifestation of systemic discrimination against women in the workplace (Agocs, 2002). Compensation regimes at workplace reveal the existence of such systemic discrimination, with some members subjected to a relative disadvantage (Agocs, 2002). The responses to the questionnaire suggest the existence of the disadvantage with many participants responding that there is lack of equal treatment, that there are concerns and problems with pay or salary, and that it is recommended that pay parity and equality at workplace be ensured in order to improve the experience of the employees. In literature, it is considered that compensation cultures is one of the important indicators of systemic discrimination and that the issue of pay parity is a serious and ongoing issue in the workplaces around the world, with women being paid lesser than their male counterparts for work of equal value (Schwanke, 2013). This is also confirmed in the questionnaire responses to three of the questions in the survey. The phenomenon of gender inequity at workplace as reflected in the lack of pay parity is considered to be almost universal in nature (Mandel & Semyonov, 2014).

In this study as well, there are indications that despite there being a number of European laws and directives of the issue of gender equity at workplace and pay parity, there are still concerns regarding whether these laws and directives are being met in the conditions in the workplace. Participants have reported to experiencing inequality, lack of pay parity, and even over work and exposure to abusive and hazardous elements at their workplace. This suggests that some of the objectives of the laws and directives are not being met by the conditions at the work place. While literature does suggest that the structural nature of the issue of lack of pay parity in the workplace can be properly addressed through legislation (Krahn & Hughes, 2007), this is not necessarily borne out by the findings of the questionnaire in this study. The experience of countries that have adopted legislation to ensure pay parity has been positive to some extent because legislation makes it mandatory for the employer to provide equal pay for work of equal value (Krahn & Hughes, 2007). However, it is not a given that all employers would follow the legislation in law and spirit. The findings of the questionnaire suggests that there are still important issues with relation to the negative experience of a significant number of employees who are women in terms of their conditions of work as well as the salary paid to them. These issues are dealt with in the law developed by the EU. The TFEU, Article 157 (1) is one of the steps taken; nevertheless, there are still some gender pay gaps in many European countries (European Commission Employment, 2009). The Council Directive 75/117/EEC of 10 February 1975, and the Council Directive 2006/54/EC of 5 July 2006 on the Implementation of the Principle of Equal Opportunities and Equal Treatment of Men and Women in Matters of Employment and Occupation are also important steps. Still, the responses of the participants indicate that some of the objectives of these steps are not as yet met and there are important issues with regard to pay parity and even conditions at the workplace, which are not being addressed at this time. The recommendations of the participants also indicate that the steps taken by the EU so far (which include the mandating of pay parity at workplace) may not have led to the actual ensuring of the pay parity regime to all the female employees across all sectors of the workplaces. This despite, UK enacting the Equal Pay Act 1970, and the courts laying down the law that women employees are paid equally for the work of the same value (Macarthys Ltd v Smith (1980) ICR 672, 1980). Therefore, the important finding of the questionnaire is that all the women employees are not as yet assured of equal pay for work of equal value. This means that there are gaps in the implementation of the laws and directives of the EU as well as the laws in the UK with respect to ensuring of gender justice in the workplace as manifested in the compensation regime. Conclusion The European Union has taken some important steps in legislating for ensuring equal pay for equal work. The principle of equal pay is considered to be an essential principle with regard to the establishment of the common market. Literature explored in this research study has indicated that the issue of pay parity is a serious and ongoing issue in the workplaces around the world, and women are generally paid lesser than their male counterparts for work of equal value. Lack of pay parity in the workplaces is a manifestation of systemic discrimination against women in the workplace, and as such, the patterns of discrimination are part of structural and cultural organisational behaviour and decision-making processes. Absence of pay parity is depicted by the differences in the compensation given to the members of the workplace when some members are subjected to a relative disadvantage vis a vis the others by being paid less than the others. Because the patterns of discrimination, including those that are related to the payment of compensation for work are systemic, they reflect the already established and embedded cultures of discrimination that marginalise some

groups of employees, such as, women. This makes it difficult for the marginalised employees to receive redressal against discrimination unless there are positive measures adopted by the organisation to reform organisational culture and adopt gender equity related practices, including pay parity. Although pay parity and gender equality at workplace has received significant attention from literature and has come to be recognised as part of concept of human rights of women at workplace, literature also indicates that there is significant absence of pay parity and that it is a universal problem. Lack of pay parity amounts to gender discrimination and has significant negative implications for female employees’ motivation, satisfaction, commitment, and the stress levels. As such, the employer’s failure to pay equally for work of equal value to both male and female employees can have negative impacts for the rights of women to work and employment and for these reasons it has implications for human rights of the employees. The human rights law under the sphere of international law has responded to the problem of lack of pay parity. Some of the most important steps in this direction have been taken in the European Union where legislation related to pay parity in the workplace already exists. The advantage of legislation is that it makes it mandatory for the employer to provide equal pay for work of equal value and is considered to be an effective way of achieving the agenda of equality in employment through bold public policy initiatives. This is also substantiated by the Canadian experience where legislation has been introduced to ensure pay parity by making it lawfully binding on the employers to provide equal pay for work of equal value so that employers have legal obligation to ensure equal pay for work of equal value in Canada (Krahn & Hughes, 2007). The European Union has also enacted legislation and enforces pay parity norms through the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Article 157 (1). This is the most important provision on the right to equal pay for work of equal value in the European Union. There is some academic disagreement on whether Article 157 (1) defines ‘pay’ in a satisfactory manner from the perspective of its interpretation because there is an argument that the definition is as yet not clearly developed and therefore fails to protect the right of women for equal pay for equal work under varied circumstances. The findings of the study demonstrate that there is some merit in the argument that European Union fails to protect the right of women for equal pay for equal work under varied circumstances because the law is evolving as yet and there are words like pay and workers that are open to interpretation. The findings of this study suggest that a significant number of participants report to exposure to hazard or harm at workplace. It is also shown that a number of participants have problems, issues or concerns with their salary. A high number of participants have also reported to absence of equal treatment at workplace, which also includes lack of pay parity for workers of similar description. While a majority of the workers do report that their workplace has equal treatment, a significant number of workers do report that such equal treatment is missing at their workplace. This is an important finding of this study because it reflects that a significant number of workers may still be facing discrimination at workplace. More importantly, participants suggested improvement in salary related norms and transparency to improve their work experience. The principal finding of this study is that a significant number of women in workplaces are yet to experience complete pay parity with their male colleagues. In this context, even the fact that European legislation and directives are created to ensure that pay parity is achieved, has not been effective enough to achieve the objective of ensuring equal pay for equal work. There is a difference between the law and the actual social experience of employment. There

Article 157 is open to interpretation. The words pay, worker, and work of equal value have to be interpreted by the courts to determine whether the petitioner has been subjected to work conditions that indicate lack of pay parity. The cases decided by the European Court of Justice suggest that while the court has interpreted these key terms in a wide sense, there are still areas of concern, such as, when the comparison is between permanent and temporary employees. In such cases, the term workers may not apply. This may become a method by which female employees may be deprived of right to equal pay without attracting the protection of Article 157. Therefore, it is recommended that the law on equal pay for equal work be made more clear through the defining of the key terms in the law itself instead of an overreliance on the courts to interpret these terms and give effect to these interpretations.

References:

- Agocs, C. (2002). Canada’s employment equity legislation and policy, 1987-2000: The gap between policy and practice. International Journal of Manpower, 23(3), 256-276.

- Allonby v Accrington & Rossendale College (2004) C-256/01 (2004).

- Arbeiterwohlfahrt der Stadt Berlin e.V. v Monika Bötel, [1992] ECR I-3589 (ECR 1992).

- C-7/93: Bestuur van het Algemeen Burgerlijk Pensioenfonds v G. A. Beune (1994 ECR I‐4471). (1994). Blau, F. D., Brummund, P., & Liu, A. Y. (2013). Trends in occupational segregation by gender 1970–2009: Adjusting for the impact of changes in the occupational coding system . Demography, 50(2), 471-492.

- Burri, S., & Prechal, S. (2014). EU Gender Equality Law: Update 2013. European Commission. European Network Of Legal Experts In The Field Of Gender Equality. Chalmers, D., Davies, G., & Monti, G. (2014). European Union Law: Text and Materials. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Channar, Z. A., Abbassi, Z., & Ujan, I. A. (2011). Gender Discrimination in Workforce and its Impact on the Employees. Pakistan Journal of Commerce & Social Sciences, 5(1), 177-191.

- Costa v Enel (1964) 6/64 (1964). Deborah Lawrie-Blum v Land Baden-Württemberg, ECR 2121 ( 1986). Douglas Harvey Barber v Guardian Royal Exchange Assurance Group [1990] ECR I-1889 (1990). Eileen Garland v British Rail Engineering Limited , [1982] ECR 359 (ECR 1982). European Commission. (2017). EU action against pay discrimination. European Commission.

- European Commission Employment, S. A. (2009). Opinion on The effectiveness of the current legal framework on equal pay for equal work of work of equal value in tackling the gender pay gap. European Commission Employment. Foster, N. (2012). EU Law Directions. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Gabrielle Defrenne v Société anonyme belge de navigation aérienne Sabena, 43/75 (1976). Gillispie and Others v Northern Health and Social Services Board and others, (1996) ICR 498 (ICR 1996).

- IDS. (2008). Equal Pay: Employment Law Handbook. Sweet & Maxwell. Joan Gillespie and others v Northern Health and Social Services Boards, Department of Health and Social Services, Eastern Health and Social Services Board and Southern Health and Social Services Board C-342/93. (1996). Joseph Griesmar v Ministre de l'Economie, des Finances et de l'Industrie et Ministre de la Fonction publique, de la Réforme de l'Etat et de la Décentralisation Case C-366/99 (2001) (2001).

- Krahn, H. G., & Hughes, K. (2007). Work, Industry & Society. Toronto: Nelson.

- Lambert, B., McInturff, K. E., & Lockhart, C. (2016). Making Women Count: The Unequal Economics of Women's Work. Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Centre canadien de politiques alternatives.

- Mandel, H., & Semyonov, M. (2014). Gender pay gap and employment sector: Sources of earnings disparities in the United States, 1970–2010. Demography, 51(5), 1597-1618.

- Macarthys Ltd v Smith (1980) ICR 672 (1980).

- NorthWestern Health Board v McKenna Case C - 191/03 (2005). Schwanke, D. A. (2013). Barriers for women to positions of power: How societal and corporate structures, perceptions of leadership and discrimination restrict women's advancement to authority . Earth Common Journal, 3(2), 1-21. Simpson, R. (2004). Masculinity at work: The experiences of men in female dominated occupations. Work, employment and society, 18(2), 349-368.

- Susanna Brunnhofer v Bank der österreichischen Postsparkasse AG, Case C-381/99 [2001] ECR I-4961 (2001). Susanne Lewen v Lothar Denda, [1999] ECR 7243 (ECR 1999). Ursula Voß v Land Berlin , I-10573 (ECR 2007).

Continue your journey with our comprehensive guide to Unveiling the Social Media Landscape.

- 24/7 Customer Support

- 100% Customer Satisfaction

- No Privacy Violation

- Quick Services

- Subject Experts